|

|

The new Jacksonian Democrats The new Jacksonian Democrats Financing democracy Financing democracy  The Webster-Hayne debate over slavery in the western territories (1830) The Webster-Hayne debate over slavery in the western territories (1830)  The Indian removal (1830s) The Indian removal (1830s) The Van Buren presidency (1837-1841) ... and the economic Panic of 1837 The Van Buren presidency (1837-1841) ... and the economic Panic of 1837The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 220-230. |

|

|

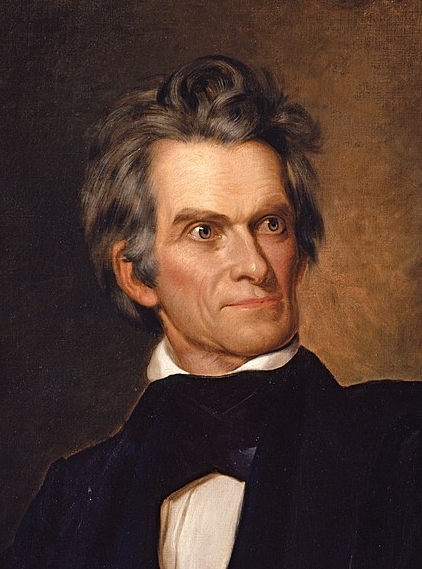

The new Jacksonian Democrats. One of the unintended and unwanted

achievements of the one-term Adams presidency was the creation of a new

and very strong political force, the Democratic Party, whose sole

purpose – besides supporting Jackson in every way possible – was to

block Adams in every way possible.

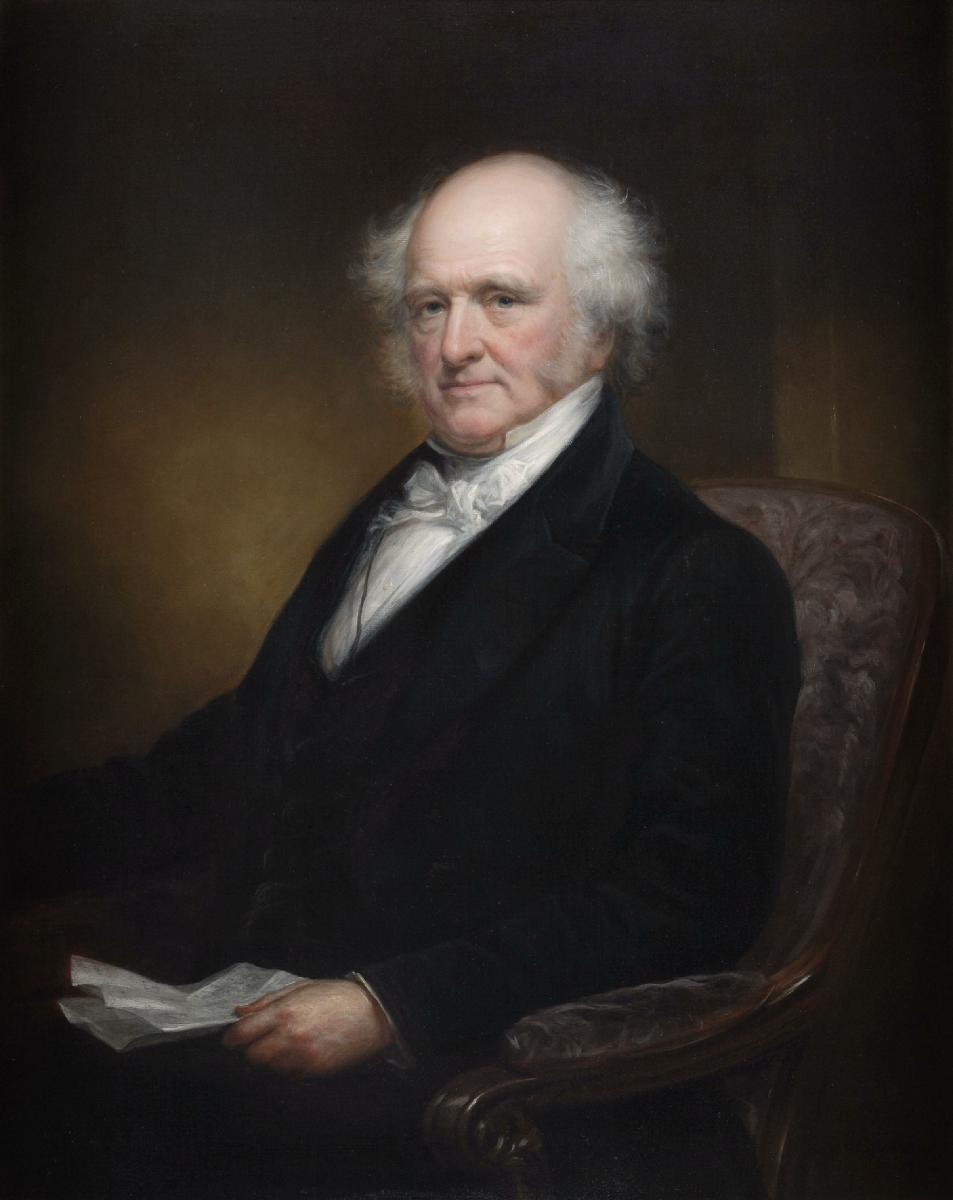

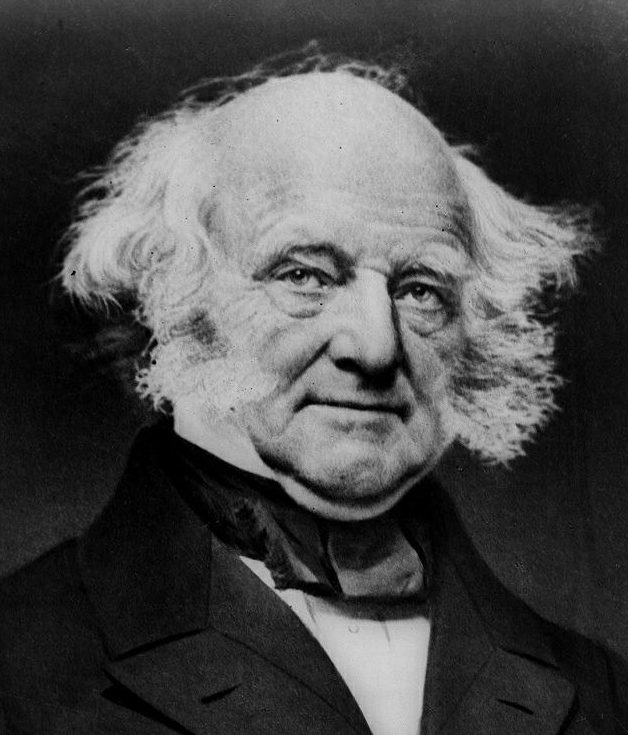

Instrumental in getting this new political force organized was Martin Van Buren, a New Yorker who personally had an intense dislike of the remnants of the upper-class Whig elite of the American Northeast who held to the older notion that politics (and economics) should be directed by society's better elements: lawyers, bankers, manufacturers, shippers, etc. Jackson's (and Van Buren's) Democrats represented the other side of the social scene: the common man, the day laborer, the Western woodsman, the trapper, the river boatman, but especially the farmer, the backbone of American society. Where the Southern aristocrat fell in this newly rising social order was complex. The Jeffersonian aristocrats were themselves moved aside by this new political arrangement. The older Jeffersonian Republicans nonetheless would identify with the new Democratic Party, because of its Southern/Western orientation. But the days when the Southern aristocrats would preside over the Southern/Western political caucus were over. Mostly they continued to exercise whatever influence they could from behind the scenes. Out front, leading the political caucus were the brash, unrefined, champions of the people. |

|

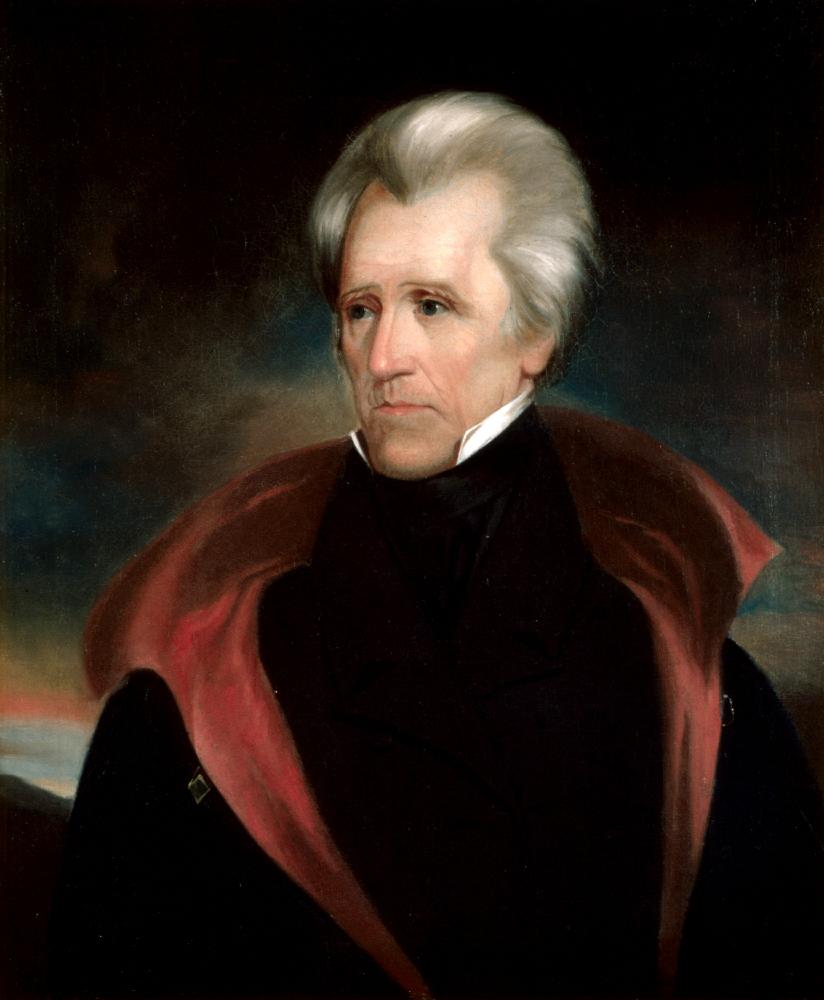

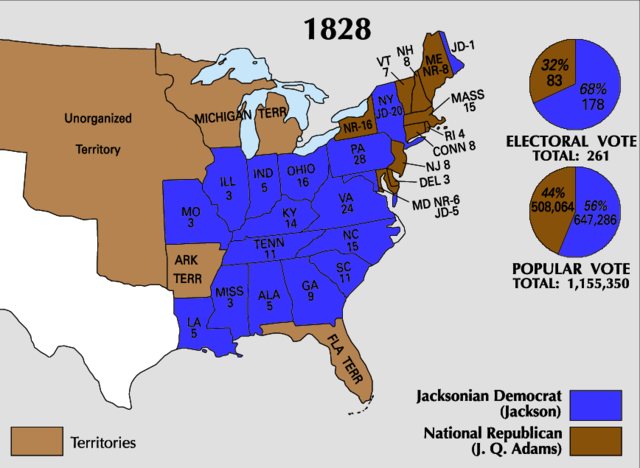

The

1828 election

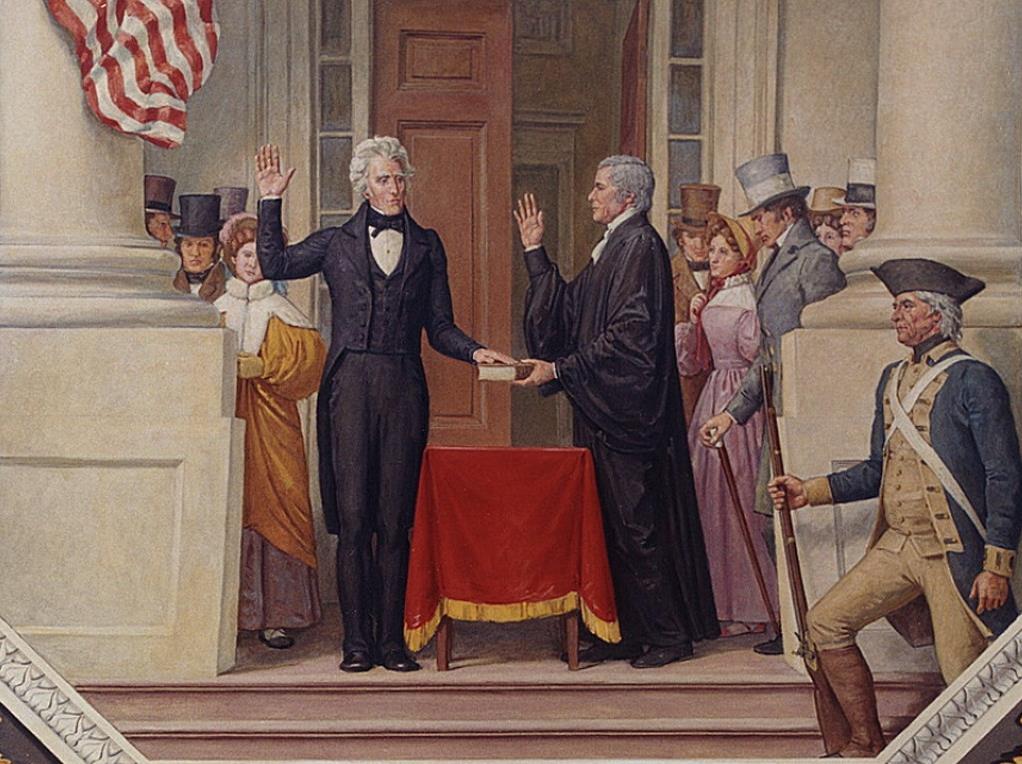

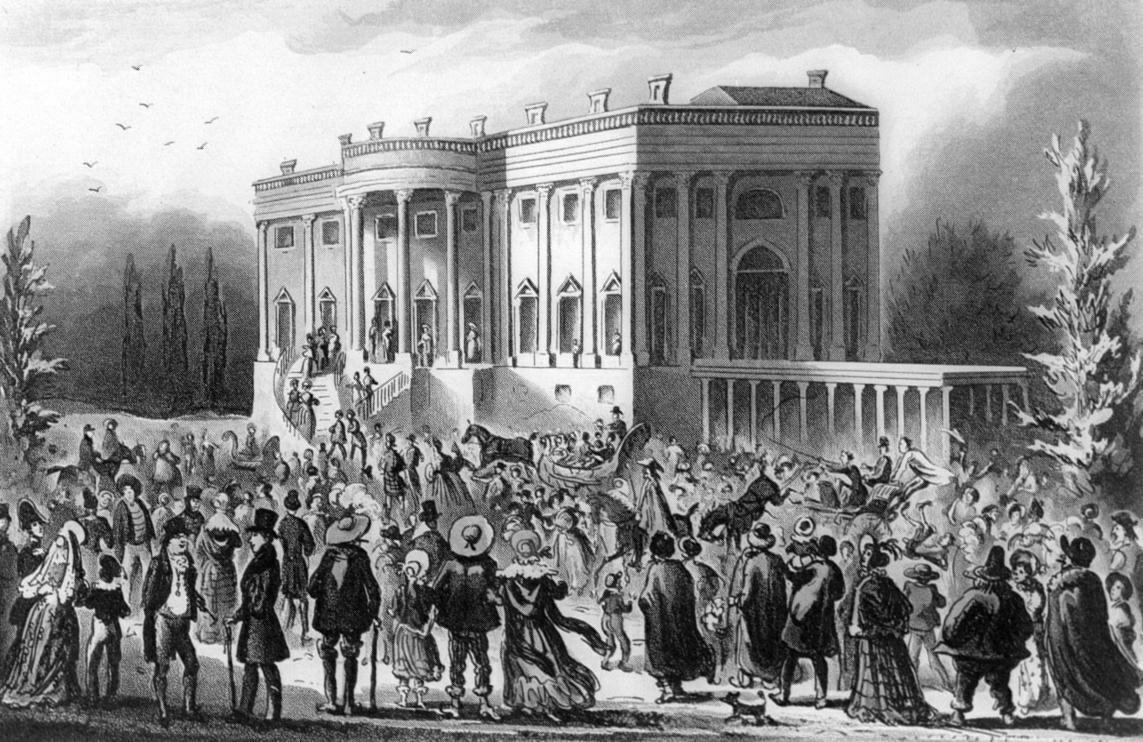

This election was vulgar in tone, with candidates – or their supporters, anyway – hurling coarse insults against each other.1 But the results regardless were a major landslide victory for the Westerner, Andrew Jackson (Tennessee) and his running mate, the Southerner John C. Calhoun (South Carolina). So, Adams was out. Like his father, Adams quietly slipped away from Washington without attending the inauguration of the new president. Andrew Jackson (supported by Van Buren) was projected as a man of the people, in contrast to Adams who was portrayed as a New England elitist, a social snob. On both counts this was a major exaggeration. Adams was colorless in personality, but in his own way was as interested in the welfare of the American people as Jackson. Jackson played to the crowds. Indeed, on inauguration day, throngs of very ordinary people attempted to gather to see and hear their hero being sworn in as president, and then join him at the White House for a major reception. Even in through the windows the crowds came, muddy boots and all, stepping on the furniture, knocking over tables, smashing china. Jackson slipped away from the adoring crowd and quietly had dinner with close associates. Jacksonian democracy was all a grand show, but one for which Jackson himself had no personal interest. He would let Van Buren take care of the political image-making. As for Jackson, he had other things he would rather be doing! 1In

the case of Jackson, it was slander about the legality of his marriage

to his wife Rachel, so vicious that it may have been the reason Rachel

died of a heart attack in December 1828, shortly after Jackson's

presidential victory, but before he was sworn into office. Jackson,

understandably, remained forever bitter about this incident. |

| Van Buren understood the process of winning elections in this day of rising "democracy" better than the older elite-led political parties (both the old Jeffersonian Democrats and the newer – and rather Whiggish – Republicans. |

| So,

the age of elite-led politics was over. The noblemen (Washington, Adams

Sr., Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Adams, Jr.) who formerly had

quietly assumed the presidency in order to serve the nation, would now

be replaced by the politically ambitious, who knew how to work the

political imagery necessary for getting elected to public office. In

this Van Buren, on behalf of Jackson, was a genius. He understood what

it took to appeal to the common voter. He understood the press and its

ability to create reality. He knew how to line up voters and get them

to the polls, especially in the newly emerging democratic age of the

general electorate.

With the advent of full democracy (at least with respect to the House of Representatives), there was a much lower voter turn-out percentage-wise than in the days when voting rights were tied closely to property ownership. Voting then was viewed as a responsibility, and the turn-out proportionately vastly greater, even though the total numbers were also vastly lower. Now it would take all kinds of political cleverness to get sufficient voter turnout to get a candidate elected in a very competitive election. Paying for rounds of whiskey or beer for those who came out to vote for a candidate was probably the most obvious technique employed.

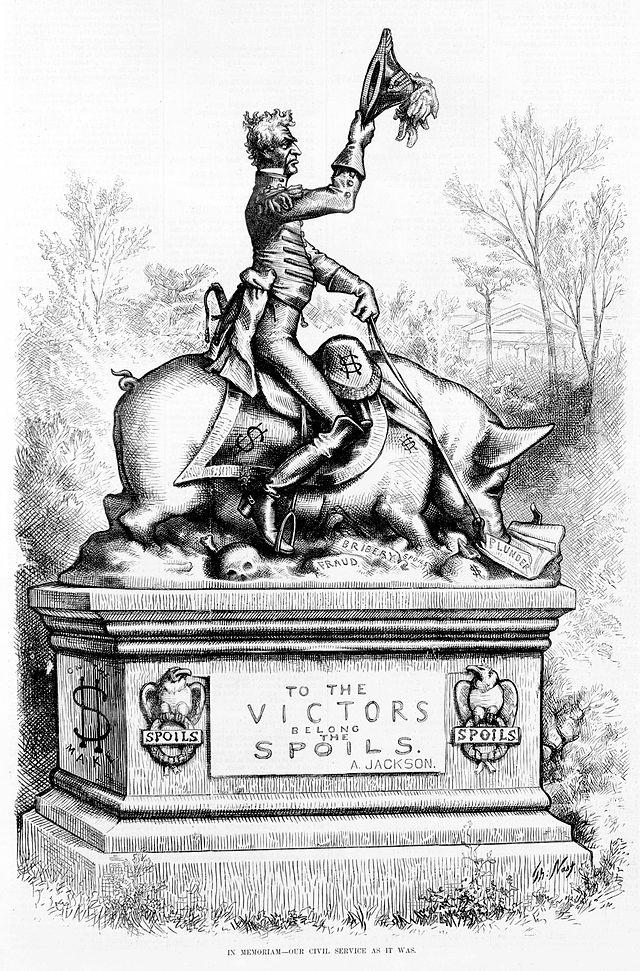

The spoils system2

This term derives from the manner in which Andrew Jackson treated his electoral success in 1828. For a successful political candidate, the greatest form of spoils was the numerous offices to which he could appoint his supporters. Thus with a candidate's electoral success came long lines of job-seekers, each hoping to get an appointment to a public job. In those days there was no professional civil service, selected through special qualifying exams for various government jobs. Instead jobs were filled on the basis of personal support of a candidate, regardless of whether a person was qualified or not. Such a payoff for electoral support was simply what everyone under the new democracy expected from the political system. That's how democracy was expected to work. 2From

the statement coined by New York Senator Marcy, "To the victor belong

the spoils," following Andrew Jackson's election to the U.S. presidency

in 1828. |

Jackson was quite open about using Presidential power for personal political purposes

including all political offices to be filled

"To the victor belong the spoils" subtitled: "In memoriam – Our civil service

as it was"

(pretending to be a quote of Jackson)

Cartoonist Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly, 28 April, 1877

|

|

A great warrior and political charismatic Jackson

was indeed. But a presidential administrator obligated to help keep the

vast American economy healthy, Jackson was not. As a result, the young

nation would face a series of crises that would challenge the heart of

its economy – and its politics.

A part of the problem had already taken root in the last year (1828) of the Adams presidency over the question of tariffs. Tariffs on imported goods were understood to serve a dual purpose: to protect the American producers from cheaper goods coming from India (cotton) and machinery (England), and to pay for all the infrastructure projects reaching into the expanding American West, such as roads and canals. The tariffs themselves were disruptive of American political interests, as protection of one industry, such as the higher price of Southern cotton, came at a great cost to another industry, such as the New England textile mills that needed cheap cotton to compete with cheaper English textiles. Thus when a bill was introduced in Congress in 1824 to raise a whole range of duties on imports, it was met with mixed emotions, and took four years to finally pass. When it did, it plunged America into a new crisis, political as well as economic. A grand strategy of Calhoun, who introduced the bill, was to call for an increase in the tariff so high that (he presumed) his own bill would naturally be killed. He and the fellow Jacksonians were actually opponents of the increase, seeing no great benefits to themselves in this legislation. But the New Englanders, including even Van Buren, were not shocked into opposition as Calhoun had hoped, so the bill advanced slowly, almost imperceptibly, until in 1828 the Tariff of Abominations was passed (over finally Calhoun's own strong opposition!). With Jackson and Calhoun swept into power in the 1828 elections, the two running mates would find themselves slowly splitting in their political philosophies, in no small part due to the new tariff. Jackson turned out to be a major supporter of the tariff, for it afforded him the monies needed to pay for roads and canals of special interest to his political supporters in one state or another. True, most roads were private or state funded. But the truly big projects, such as the national road west into Ohio could be funded only by a larger single source, namely the national government. And Jackson enjoyed being in the position to oversee just such development, especially when he could use his power to exclude similar projects in the states of his political opponents! Calhoun, however, saw the expanding powers of the national government increasing the potential of granting it greatly increased authority to take action in other areas, such as in the question of slavery. As a politically sensitive Southerner, Calhoun was well aware of the growing swell of anti-slavery sentiment growing in the North and was fearful that the rapidly increasing Northern population would eventually give Congress sufficient votes to ban the practice of slavery altogether. As a result, Calhoun, once a strong nationalist, now became an increasingly strong voice in support of states' rights, meaning that the states, not the national government, should have sole right to determine their position on the slavery issue. This would throw President Jackson, a strong nationalist, into increasing opposition to his vice president, Calhoun. Thus with the new round of presidential elections coming up in 1832, Jackson replaced Calhoun with his loyal supporter Van Buren as his new running mate.

Western land sales

The other chief means of raising federal revenue besides tariffs was the sale of Western land. New Englanders wanted the land sales to slow down because it drained off workers needed in the New England factories. Southerners however were big supporters of the opening of Western land for sale, in part because, with slavery, the South was not really the land of opportunity for its slowly rising White population and because cotton production tended to deplete the energy of the soil. Therefore new lands were needed to be opened up for cotton production. Thus whereas the North proposed increasing the price of Western land (presumably to increase federal income), the South proposed the opposite: to lower the price of land, and if no buyers could be found, to simply give the land away. Thus along with tariffs, the issue of land sales deepened the North versus South (and West) split. |

|

|

The Webster-Hayne debate (1830)

And here too in the land sale debate, the issue of slavery would insert itself. The opening of Western lands would always bring forward the question of whether this new territory was to allow slavery or not. Thus the great debate between the Northerner Daniel Webster and the Southerner Robert Hayne about Western land sales quickly turned itself into a question about the future of slavery. But it also even got down to the question of the future of the country as a united people. Hayne raised the specter of a South being forced to change its lifestyle by an imperialist North and countered with the old Jefferson-Madison nullification doctrine, that the Union was simply an agreement among sovereign states and that the states themselves had the final say on what went on politically within the Union. The implication was that if the states did not agree with political developments, they had even the right to secede, to end that relationship and go off on their own (as the New Englanders themselves had considered doing during the days of the War of 1812). Webster countered that the very freedom enjoyed by the nation, a nation created by the people themselves and not just the states, was a result of the tremendous strength of the Union, and that to lose that unity was to lose the freedom that Americans enjoyed. It was now easy to see that the new nation was headed for major trouble over this very strong cultural split which ran through its very heart, multifaceted in character, combining the issues of federal revenues, Western expansion, economic lifestyles (feudal vs. industrial), and ultimately slavery, forging itself into a sharp sword which was cutting the country in half. Slavery especially stood at the heart of the division, for the idea of a White man holding a Black man in subjugation as property was understood to be vital to the very life of the South – and at the same time understood by the North as a gross sin likely bringing the wrath of God down on a people allowing such an abomination to occur within its society.

The 1836 Gag Rule

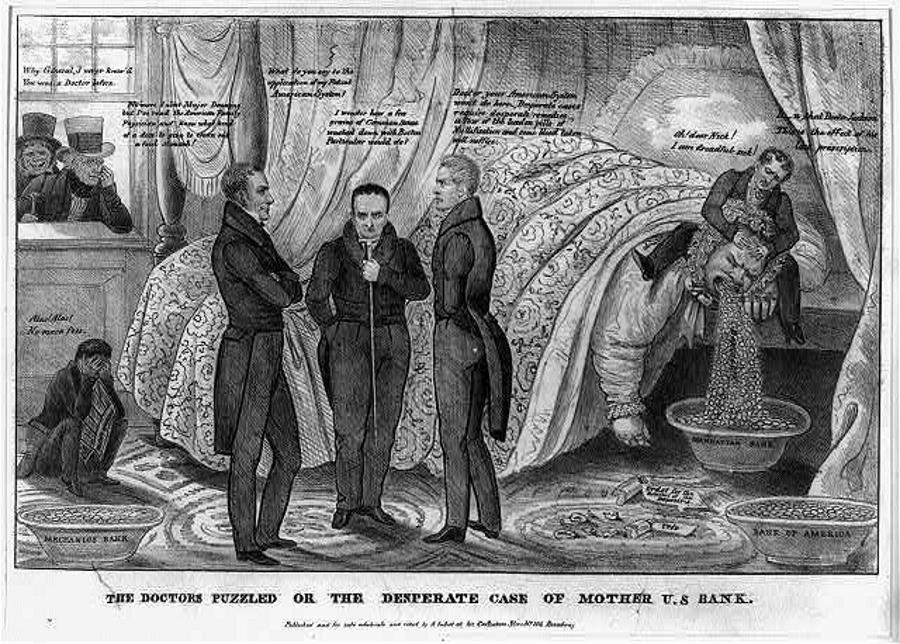

There seemed to be no way to bridge this widening cultural gap. Eventually, however, Congress came up with the supposedly ingenious idea (proposed by Representative Henry Pinckney of South Carolina) that the way to avoid the slavery issue from causing an irreparable split in the country was to get congressmen to agree simply to avoid the subject, not ever to bring it up in discussion. The explanation was that it was a state issue anyway and Congress had no constitutional right to interfere in the matter. Whereas this may have helped smooth the problem over in the short term (but most politicians trend only think in the short-term anyway, or at least only as far forward as their next election) avoiding the subject ultimately meant that it would become even harder to resolve in the future. Jackson and the 2nd Bank of the United States (BUS) Jackson was coming up for reelection in 1832, opposed in the electoral campaign by his old adversary Clay. In the midst of the campaign the BUS got dragged front and center into the Jackson-Clay battle. The question was not most importantly one of economics, such as the issue of coin versus paper money (which was a favorite subject of dispute among American politicians), as much as it was one of political patronage. The BUS was coming up for a renewal of its charter in 1838, though its supporters proposed an early renewal just to get things squared away sooner. But the fact that it was Clay and his supporters who made the proposal automatically infected the idea in the eyes of Jackson. Jackson was not opposed to the BUS in principle, but wanted to reshape national banking in such a way that gave him the right to preside over the personnel and policies of such a bank. A national bank was a huge source of patronage, and Jackson disliked the idea that the BUS seemed to be the instrument of the up-East business class. He especially disliked it when Clay threw his support to the renewal of the BUS charter because it meant securing Clay's BUS patronage rights if the charter were renewed, and the loss of Jackson's patronage rights if his own idea of a national bank were thus set aside. Consequently, Jackson decided to fight the BUS with all of his typical Jacksonian ferocity. |

|

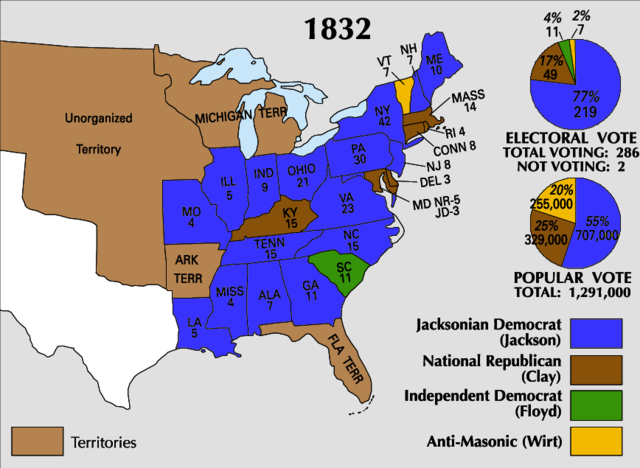

The election of 1832

Thus the BUS became a major issue in the election of 1832. Jackson used all of his folksy language to depict the BUS as the tool of the up-East elite, succeeding in connecting his opponent Clay in the minds of the common folks with greedy elite trying to take the country away from the people. The strategy worked, and Jackson was reelected by a large popular majority and an even larger majority in the electoral college. Thus Jackson would be president for another four years, with Van Buren as his new vice president. And Jackson would withdraw all government deposits and suspend all future business with the BUS in 1833, depositing government funds instead in a number of state and local banks, termed by his opponents as Jackson's "pet banks." He would block the renewal of the BUS's charter in 1836, and ultimately leave it struggling as something of a private bank (which finally closed in 1841), leaving the U.S. government without a strong financial instrument to combat economic crises, a major one which exploded in 1837 and lasted until revival finally began to occur in 1842/1843. |

|

|

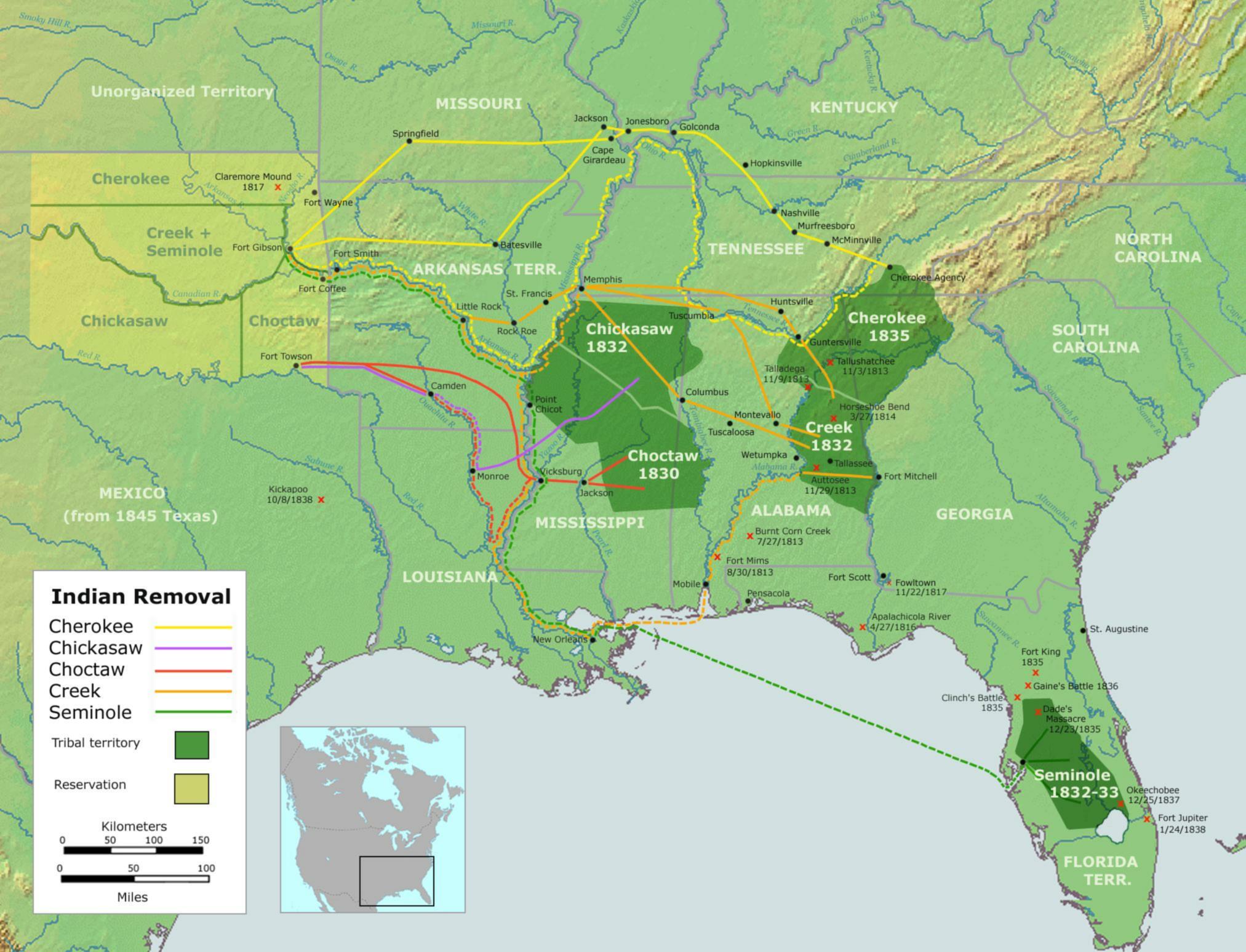

The Indian Removal (1830s)

Although Jackson had great respect for the American Indians as warriors, he nonetheless had no particular compassion for them as they faced the pressures of an ever-expanding Anglo population. And Jackson, ever-sensitive to his image as champion of the common (White) man, knew what his supporters' sentiments were with respect to the Indian: they wanted them removed as far away as possible from their own world. And in general, that meant moving the Indians beyond the Mississippi River. This process had been urged since early in the Republic, had been going on slowly under various presidents, but had stalled during John Quincy Adams' presidency. Jackson's supporters in the Deep South (Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi) wanted the process resumed. If the federal government was not going to take action, then the states would – as part of the principle of states' rights Particularly interested in such removal was the government of the state of Georgia, which eyed the Cherokee lands with envy. The fact that the Cherokee were Christians, literate, settled as farmers and peaceful, came as no defense in their effort to hold on to their ancestral lands. Also, the discovery of gold on Cherokee land made the situation for the Cherokee even much worse. The government of Georgia wanted the Indians gone, and signed a treaty with some compliant Cherokee chiefs authorizing the purchase of Cherokee land, coupled with the promise of land in the Oklahoma Indian territory as additional compensation. But thousands of Cherokees refused to accept the treaty. Meanwhile Jackson got into the act, in part to bring the federal government rather than the states as the ruling voice in this issue. He pushed through Congress the Indian Removal Act of 1830 requiring the Indian tribes of the South to move west of the Mississippi River, principally to the designated Indian territories of present-day Oklahoma. The bill had originally implied that the removal would be voluntary. But by the time the bill was finalized the voluntary part had been lost along the way. Cherokee attempts to fight the legality of Indian removal finally reached John Marshall's Supreme Court, which on the one hand had determined in 1831 (The Cherokee Nation v. Georgia) that the Cherokee had no right to be treated as a sovereign nation, but on the other hand in 1832 (Worcester v. Georgia) that the state of Georgia had no right to engage in a treaty (forced or voluntary) with the Cherokee because that right existed only for Congress to exercise. Thus the official Georgia deal to remove the Cherokee was unconstitutional. Presumably the removal was now blocked. Or was it? Jackson supposedly replied to Marshall's decision: "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." Certainly Jackson had no intentions of getting in the way of the removal and he knew therefore that the removal was inevitably going to go forward, the Supreme Court notwithstanding.

The Indians resisted as best they could. In

Illinois the Sauk and Fox Indians, led by Chief Black Hawk, revolted

against the order and had to be put down violently by the Illinois

militia (including in its ranks Captain Abraham Lincoln).3 But one by one the Choctaw (1831), Seminole (1832),4 Creek (1834), and Chickasaw (1837) were forced to move. Finally the Cherokee were also forced to join the exodus when in 1838 General Winfield Scott and an American army confronted the Cherokee with the fact that it was now time to move. Thus in a process of removing one Indian tribe after another in the period 1831 to 1838, 46,000 Indians were relocated in order to open the way for Anglo-American settlement in their traditional lands. All Indian tribes in the Southeast were forced to make the long trek to the Oklahoma Indian Territory without adequate support in food or shelter along the way. The worst suffering occurred among some 13,000 Cherokee, who in 1838 were first herded into camps in Tennessee and then force-marched westward through a freezing, snowy winter by General Scott's soldiers. Cold, disease, and starvation took a huge toll in their numbers. Thus many died along this Trail of Tears, possibly as many as a third of all Indians involved. 3The Sauk and Fox had previously moved West across the Mississippi, but found themselves under attack by the Sioux Indians, and had moved back to Illinois, trying to avoid extinction. 4But

the Seminole were the most resistant of the Indian tribes to the

removal, engaging in savage war against the Whites from 1835 to 1842,

during which many took to hiding in the Florida swamps. Ultimately

three thousand were killed and the rest finally forced to move. |

The Cherokee "Trail of Tears" (1838-1839)

|

|

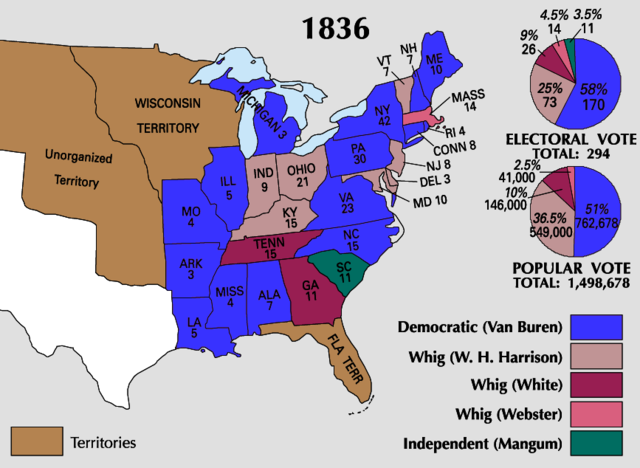

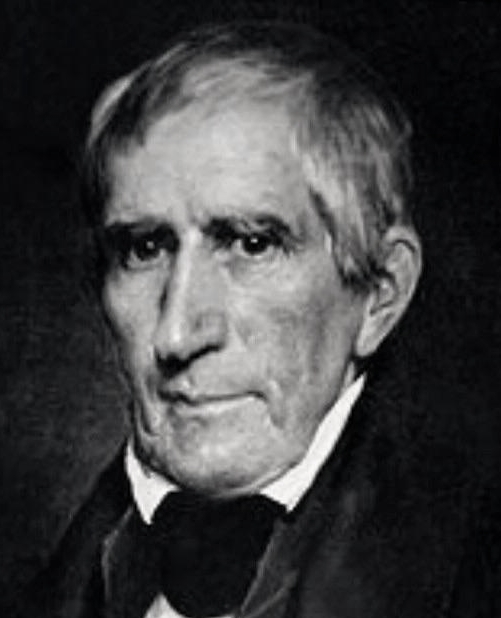

The Van Buren presidency (1837-1841)

As Jackson's chief political supporter, as secretary of state and as vice president it was inevitable that the Jacksonian Democrats would look to Van Buren to take the lead as Jackson completed his second and final term as president in early 1837. Van Buren won the 1836 election easily over his Whig5 opponents, who had mistakenly hoped that by dividing their candidacies they would throw the election into the House of Representatives where they commanded a strong majority. But little else about his presidency would be so easy. 5The

Whig Party was formed in 1834 out of the regional and social interests

of what had once been the heart of the Federalist Party: Up-East

banking and manufacturing interests. Whigs also tended to oppose

Westward expansion, in part out of the dislike of seeing slavery extend

itself Westward, and in part out of a desire to slow down the movement

of needed industrial laborers from the East to the Western frontier. |

|

The 1837 Economic Panic, and Depression (into the early 1840s)

Van Buren would be saddled with a huge economic crisis that was not really his fault (the roots of it reached back into Jackson's presidency), which nonetheless he would be personally blamed for, and which guaranteed that his presidency would be short-lived (only one term). The wild speculation in Western land, the decentralization of the banking system with Jackson's shutdown of the BUS, the extensive printing of paper money (as opposed to specie in the form of silver or gold coinage), and an overly optimistic consumer society (an economic bubble) all contributed to the crisis. But the brewing crisis itself was set off by events far away in England when the Bank of England, detecting an economic downturn in Great Britain (poor wheat harvests and the need to spend specie to purchase food from abroad), undertook policies to tighten up the money supply, sending shock waves throughout the rest of the world dependent on British finance as the international standard. This included importantly a number of American banks in the East, who were forced to follow the British lead in tightening their lending policies, sending out ripples, then waves, of financial fear into the previously overly optimistic economy. Also the land speculation bubble was quick to burst when in 1836 Jackson issued an executive order demanding that Western land payments be made in gold and silver specie rather than paper money, coinage which most people did not have. Prior to this, land speculators had been buying up huge amounts of land employing only a rather seemingly inexhaustible supply of paper money issued by the numerous state and local banks on which the value of the dollar depended now that the BUS had been shut down. Hard money advocates urged Jackson to take action, to bring real wealth into all this land speculation. And thus the 1836 Specie Circular was issued as one of Jackson's last acts as president, adding to the panic which broke out early in the next year (February-March of 1837) as Van Buren took office. Now speculators were holding land that could not be financed except by specie, at a time when those holding gold and silver specie were afraid to let go of it, hoarding it and taking it out of circulation – which merely depressed the economy further. But it was not only land speculators that got hurt but the American banks themselves that got crushed in the panic. During the bubble, banks had been issuing those same paper dollars for mortgages and personal loans, careless in connecting those dollars to the real value of gold and silver coinage held in their vaults as reserve. As panic set in, people conducted runs on their banks, demanding the exchange of their paper money for gold or silver specie, which the banks simply did not have. At this point banks had only one of two options: to call in for full payment loans and mortgages extended to their customers (but who had the money to suddenly pay off their loans in full?) or to simply close their doors. Within a short time nearly half of America's banks, especially the small ones, indeed closed their doors. Thus people held onto their money for fear that spending it might leave them penniless. But this only worsened the contraction. Prices on commodities fell as producers attempted to lure forth nervous consumers. All of this ultimately acted together to sink the American economy in a spiral downward of economic contractions affecting virtually every sector of the U.S. economy. The first and worst to get hit was the cotton export business of the American South, which had to lower cotton prices by as much as 25 percent in order to hold on to industrial customers both at home and abroad. This immediately threw the cotton-dependent South into deep recession. But wheat prices were close behind in the collapse, hurting the Western farmer almost as badly. In the industrial East, workers were let go as businesses floundered, to a point where in many cities almost a third of the workers found themselves unemployed. State governments also hung on the edge of bankruptcy, having relied on the Jacksonian banks to hold their reserves, supply them with loans, and provide a tax base (on bank profits) which allowed the states not to have to tax their voters. It had all worked very nicely in the days of the bubble. But when the bubble burst, states across the country found themselves in deep trouble, not able to finance even the slenderest of their operations. To top it off, Van Buren gave orders that the federal government would no longer distribute funds to the states (which had been part of Jackson's policy of building state support at the cost of the national government). His goal was at least to keep the national government solvent. But this only made the economic contraction all the worse. It was thus unsurprising when in 1840 Van Buren faced a disillusioned electorate and went down in dismal defeat in his bid for reelection, 234 electoral votes for his Whig opponent Harrison and only 60 votes for Van Buren. |