|

|

De Tocqueville's Democracy in America De Tocqueville's Democracy in America  The industrial revolution continues forward in the East The industrial revolution continues forward in the East Individualism and isolation of life in the opening West Individualism and isolation of life in the opening West  Unitarians and Deism also flourish in the East Unitarians and Deism also flourish in the East  The Second Great Awakening The Second Great Awakening The Mormons The Mormons The Larger Christian mission The Larger Christian missionThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 230-247. |

|

|

De Tocqueville's Democracy in America

In 1831 the Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville arrived in America, ostensibly to study the American prison system. But he and his associate Gustave de Beaumont were truly more interested in studying the American society in general, a subject of great interest to the French. Tocqueville published in two volumes the results of his study as Democracy in America, appearing in 1835 and 1840 at the height of the Jacksonian era. It provides an incredibly insightful view of the American culture by one standing outside that culture. He noted the hugely individualistic spirit of the typical American and the restlessness of the American heart, which was already looking for the next challenge before it had completed the work on a previous challenge. He also noted the spirit which defended the basic equality of all (Whites), ever-ready to challenge presumptions of superiority on the part of others. He correctly attributed the origins of this egalitarian spirit to the Puritans of New England as well as the principle of the sovereignty of the people founded in the early Puritan covenants and state constitutions. But he also noted the contradictions to all this posed by the agonizing question of slavery. Also, from a Frenchman's view with its more liberal attitudes toward marriage and the sexes, he was distressed at how rigid were the sexual roles assigned to men and women, both in and out of marriage (but this also was a Puritan legacy, unknown in France). He was also concerned about the dangers of democracy turning into a tyranny of the ignorant majority, unrestrained by the more enlightened understanding of social dynamics by society's more polished and better educated social elite. And he correctly predicted the tragedy of war that would eventually occur over the wrenching issue of slavery. In short, he described clearly the good and the not-so-good of Jacksonian America, at least as the French understood the social ideas of good and bad. |

|

|

The Industrial Revolution continues forward in the East

The restlessness of the American heart that Tocqueville noticed was clearly obvious in the incredible amount of industrial activity – and innovation – pushing the American economy ever-forward. The development of the steam engine permitted extensive mechanical operations to take place where no water power was readily available to turn the wheels of industry's many new mills appearing across the North (by 1840 there were some 1,200 cotton mills in operation, mostly in the American Northeast). Foodstuffs, raw materials, and even finished goods were constantly on the move in America – along the turnpikes and the many canals being laid out across the East. By 1818 the National Road had been completed linking the American East at Baltimore and Philadelphia with the Ohio River valley at Pittsburgh and thus providing access to the American interior all the way to the Mississippi. With the development of steam power,1 paddlewheel boats able to go both ways on the great rivers of the American interior were soon moving vast amounts of produce from the West back to the East – and people and their goods headed to new lives in the West.

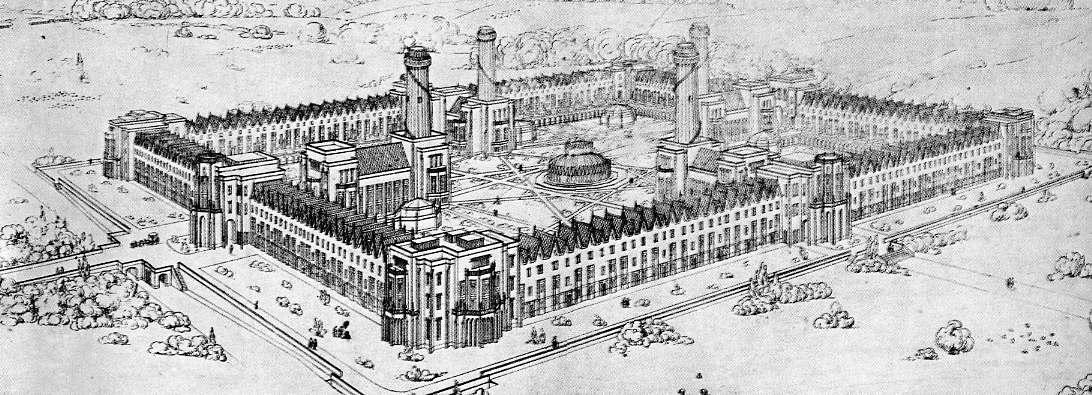

The Erie Canal

Not to be outdone by Baltimore and Philadelphia, New York, under the direction of its industrious Governor DeWitt Clinton, decided in 1817 to dig a canal from the Hudson River at Albany all the way to Lake Erie at Buffalo, thus gaining access to the American interior by way of the Great Lakes. The 363-mile project was open for business by 1825 (which turned out to be a highly profitable venture!).

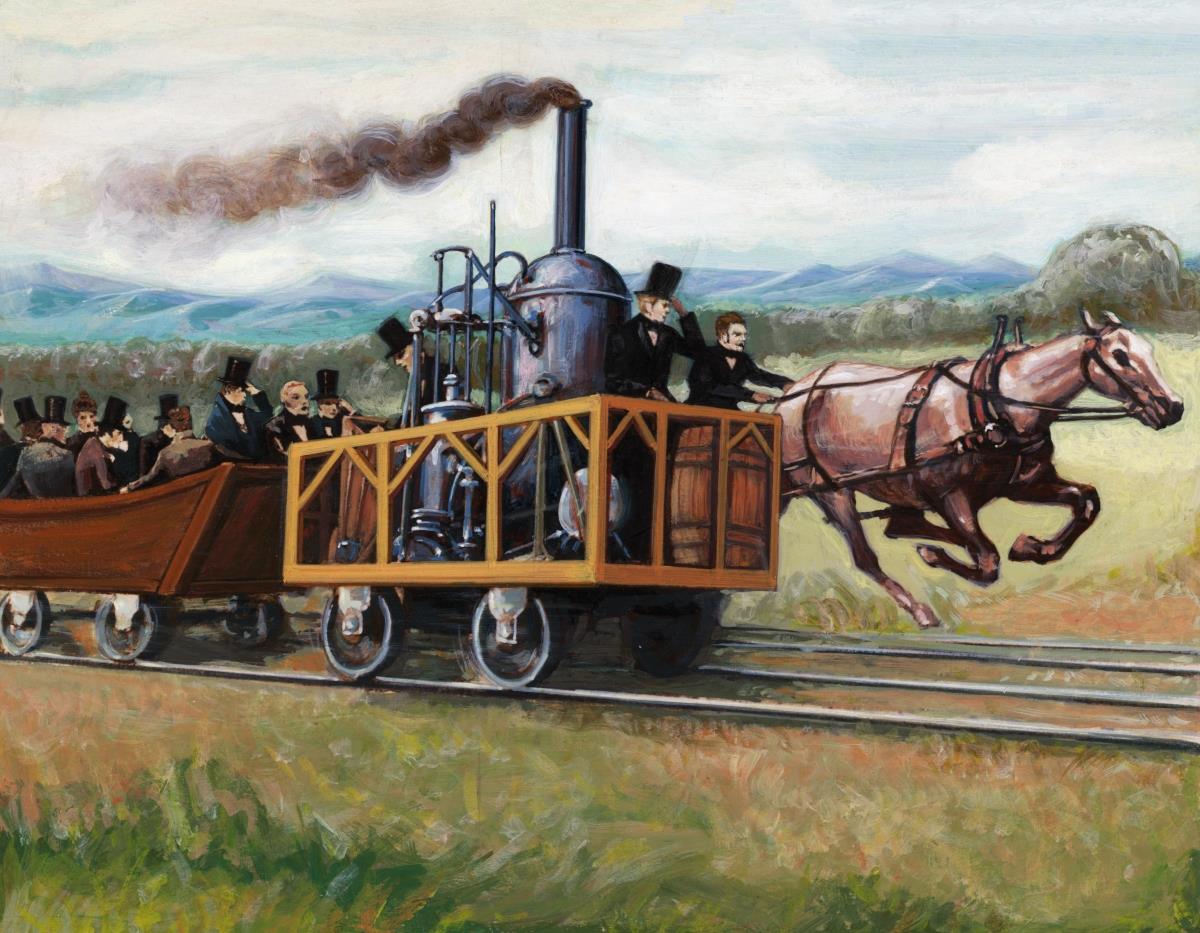

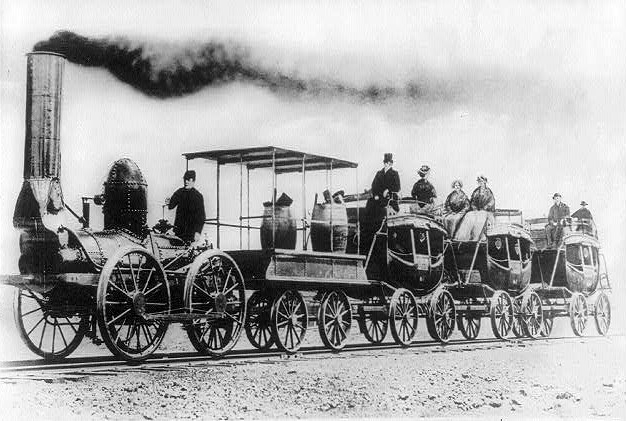

The first railroads

In 1827 the town fathers of Baltimore, seeing water traffic outbid their wagon road, decided to investigate the possibilities of laying a railroad, similar to one under development in England. In 1828 they laid the first rails and by 1830 they had completed the first portion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Then, not to be outdone by New York with its Erie Canal and Baltimore with its railroad, Massachusetts in 1830 and 1831 decided to undertake the building of a railroad across the low mountains to the West, to link Boston with Albany on the Eire Canal, completing the program by 1842. Eight years later (1850) almost 3,000 miles of rail line then connected New England towns with even the Great Lakes. And by 1852 the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first Eastern railroad to reach the Ohio River. This was such a boon to business, that the following year (1853) the mighty New York Central Railroad was formed by consolidating ten smaller railroad companies. Meanwhile in the South, in 1828 the town fathers of Charleston decided to open up their city by rail all the way south to the Savannah River (to gain some of the trade which was prospering rival city Savannah tremendously). When it was completed in 1833 it was at that point the world's longest railroad. Eventually the South extended the reach of its rail system, by 1851 reaching Chattanooga on the Tennessee River and from there ultimately Memphis on the Mississippi River.

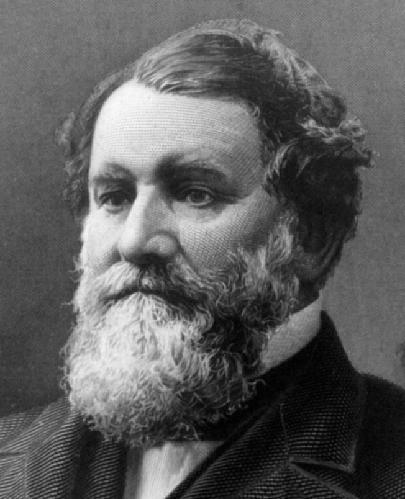

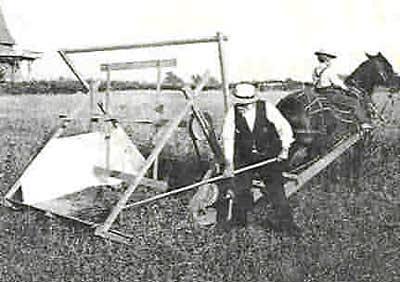

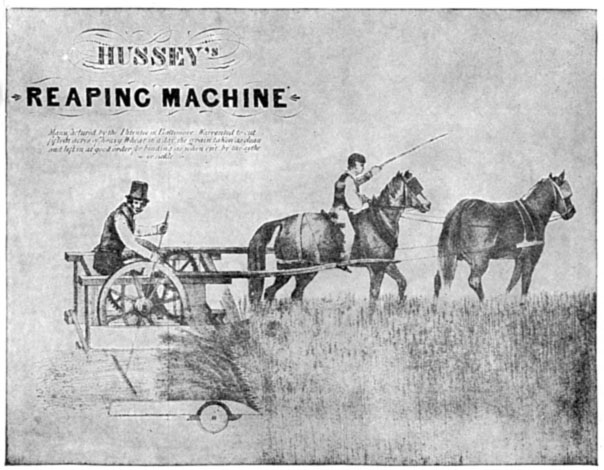

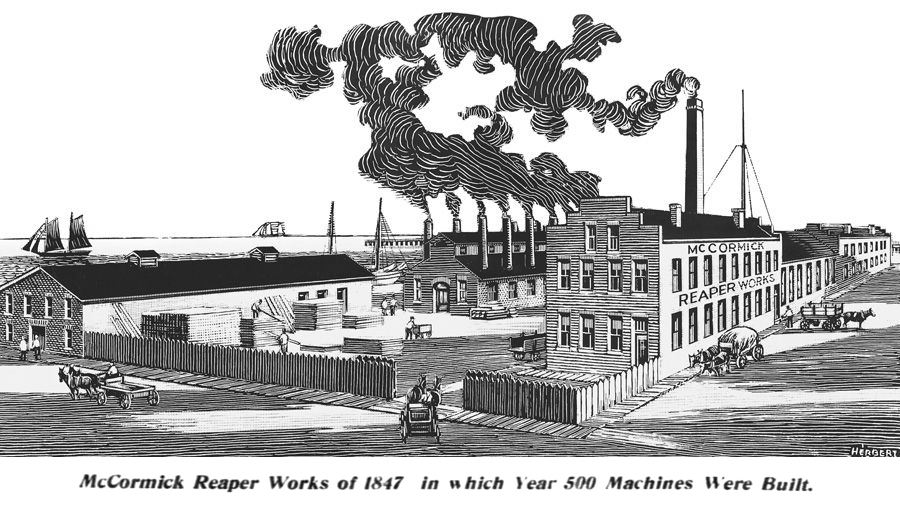

The mechanical reaper revolutionizes agriculture

In 1831 Cyrus McCormick held a demonstration of his new reaper, which with one mule and one driver could harvest wheat at six times the rate of a single farm worker.2 Needless to say, the reaper now became not only highly sought after, it soon became standard equipment on the large farms of the American Midwest, which themselves were industrial enterprises rather than just mom-and-pop operations designed merely to support a single family. 1In August of 1807 Robert Fulton's steam-driven dual paddlewheel North River Steamboat made the amazing 150-mile boat trip up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany in 32 hours of actual travel (not counting stops along the way). 2McCormick's

claim to have invented the reaper was challenged by another inventor,

Obed Hussey, whose 1833 invention was in fact a better machine. The two

improved their models and competed until Hussey was finally driven out

of business. |

|

|

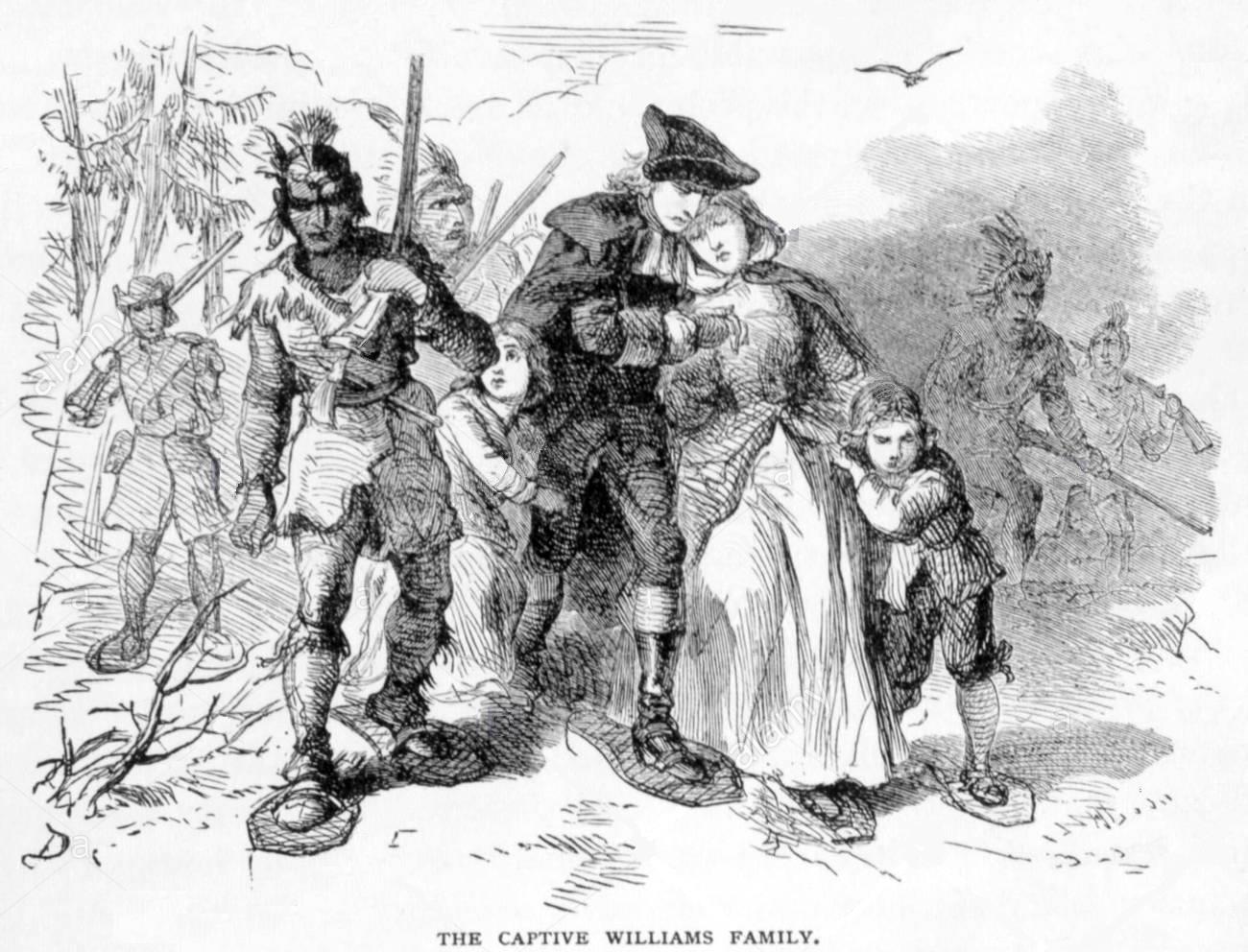

The American world was changing fast, and change itself produced its own problems, psychological as well as physical. On top of all this change, it was obvious by 1830 that the land was playing out in the East. The stony soil of New England had never been that great and – stressed by a rapidly expanding population – the region was unable to sustain a stable agricultural existence. So the 1830s and 1840s saw streams of New Englanders heading West across the Appalachian Mountains and down the Ohio River to find new homes in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and across the Mississippi into Missouri. Likewise, the cotton farms of Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia were playing out, sending settlers West into Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and even into the northern Mexico territory of Texas. Unlike the planned movements and settlements of the Puritans two centuries earlier, there was no organization or coordination to this movement. Individuals just simply up and moved in the hope of starting a new life in the West. But life in the West proved to be isolating, and dangerous under the constant threat of Indian attack.3 Yet such a life produced highly independent and self-sufficient Americans, hunters and riflemen, well able to secure meat from nature, and prepared to fend off the dangerous Indian. 3The

results were always murderous for men, women and children, or worse,

torturous, because Indians loved to gather to watch their captives

writhe in carefully administered pain until they finally expired. |

|

|

Unitarianism and Deism flourish in the East

At the same time, for others, especially those living along East-coast America, a comfortable small-town life (dependent on an economy other than just agriculture) seemed to have a natural peace and prosperity to it. Not surprisingly, life took on a more rational character, thus stepping back from its previous fervency in its Christian spirituality. Americans, especially among the more leisured professional classes, found themselves less interested in what God might do in their lives and more interested in what they might achieve for themselves under this more rational social realm emerging around them. They did not abandon Christianity, because being Christian was understood to be the same as being civilized. But the faith component (trust in God as the essential higher power in their lives) was disappearing. Its place was being taken by a rational morality, a key part of Enlightenment Humanism that was sweeping intellectual circles at the time, in America as well as Europe. Such Humanism usually claimed the moral teachings of Scripture, especially the teachings of Jesus, as its Christian foundation. But in the end, no such connection was absolutely necessary, for these were self-evident truths that any rational person would understand as the foundation of any life well lived (French revolutionaries had gone so far as to disdain even this slender Christian connection with their utopian Idealism). Once again (as in the enlightened days of the late 1600s and early 1700s) enlightened Americans of the early 1800s were convinced that Human Reason was vastly superior to the pre-scientific superstitions about life held by simpler Americans – Americans who were intellectually unable to shake off the irrational beliefs about people walking on water and raising the dead back to life. The enlightened ones were easily disdainful of those who clung emotionally to a religion drawn from a darker past. Of course, they failed to notice that their new Rational Humanism was no newer than the story of Adam and Eve's fall in the Garden of Eden or the long Biblical narrative about the repeated wandering of ancient Israel away from the counsel and discipline of God – and its tragic results.

Christian Unitarians

In the early 1800s a huge split occurred within the Congregationalist churches of New England, a split that ultimately came to center on the professorship of theology at Harvard College, a position which remained empty from 1803 to 1805. When the position was finally awarded to the Liberal Henry Ware, the conservative Calvinists left Harvard and founded the Andover Seminary. There they would be joined by the more evangelical members of the New Divinity4 group. Meanwhile, Harvard College moved off more strongly in the Unitarian direction.

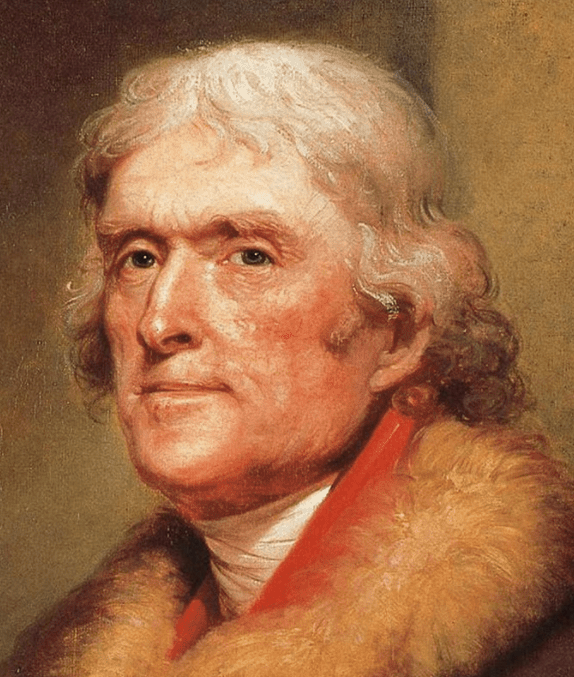

Jefferson

Another individual to figure big in this rising Humanism around this same time (but now in his later life) was Thomas Jefferson. In 1822 Jefferson wrote his friend Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse attacking the foundations of traditional Christianity, pointing out in particular the ancient apologist Athanasius and the more recent Calvin as false shepherds and usurpers of the Christian name teaching a counter-religion made up of the deliria of crazy imaginations, as foreign from Christianity as is that of Mahomet. Their blasphemies have driven thinking men into infidelity. In that same letter Jefferson (who had published an updated Bible eliminating all the miracle stories and focusing only on the moral teachings of Scripture) professed that the simple doctrines of Jesus (to love the only God with all one's heart and one's neighbor as oneself) had been perverted by adding Platonizing doctrine (Jefferson did not like Plato very much either) most evident in Calvinist dogma. But he was confident that such dark days were becoming a thing only of the past. Thus he states: I rejoice that in this blessed country of free inquiry and belief, which has surrendered its creed and conscience to neither kings nor priests, the genuine doctrine of one only God is reviving, and I trust that there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die a Unitarian.For those living in the comfort of a secure existence and untroubled by enemies or economic hard times, the promise of the Enlightenment seemed to be above and beyond all serious questioning. 4A major leader in the New Divinity movement was the religiously conservative Yale College president Timothy Dwight, who worked very hard to head off the Deism and Unitarianism spreading among the New England clergy. Dwight was also the head of the Federalist Party in Connecticut and an early supporter of the inter-faith American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABDFM) created in 1810. |

|

Robert Owen and his communitarian or socialist experiments in America

But anyway, what textile manufacturer Owen was proposing to do in his New Harmony had nothing to do with Christianity. A huge effort was made to make his New Harmony the perfect setting of purely Secular economic and social perfection. While Owen went around to promote support elsewhere for his New Harmony project, he left its supervision to his sons. They in turn ran into all sorts of difficulties when well-intended and not so well-intended individuals flocked to the project, a project that was designed to become self-supporting through the industrial enterprises Owen attempted to start up there. Some were willing to accept the responsibilities required of this communal (Socialist) venture. Many were not. Chaos quickly set in. Ultimately no moral structure (other than a breezy Humanism) underlay the project. Owen himself was strongly anti-Christian, and strongly pro-Humanist, but like all Humanists, could never figure out how to get a free people to accept social responsibilities on the basis of their own instincts. Other prominent Humanists visited and offered counsel to the community. But they got no further in getting a true social order up and running. Two years later (1827) the Owens had to abandon their project – without having learned anything in the process. |

|

Emerson and the Transcendentalists

Another version of this development was found among the Transcendentalists, who reached well beyond the purely rational world of the Unitarians and other Humanists with their mystical quest for the Divine as a higher order of disciplined thought. They sought, through different forms of spiritual discipline, to embrace Divinity both in a oneness with nature and a sense of reaching beyond even the natural. They sought to be as fully human as possible so as to find the Oneness of Divinity as fully as possible. They too tended toward lofty communalism in the hope of reaching beyond the coarse nature of selfishness and sin, to find a more perfect human harmony. |

|

|

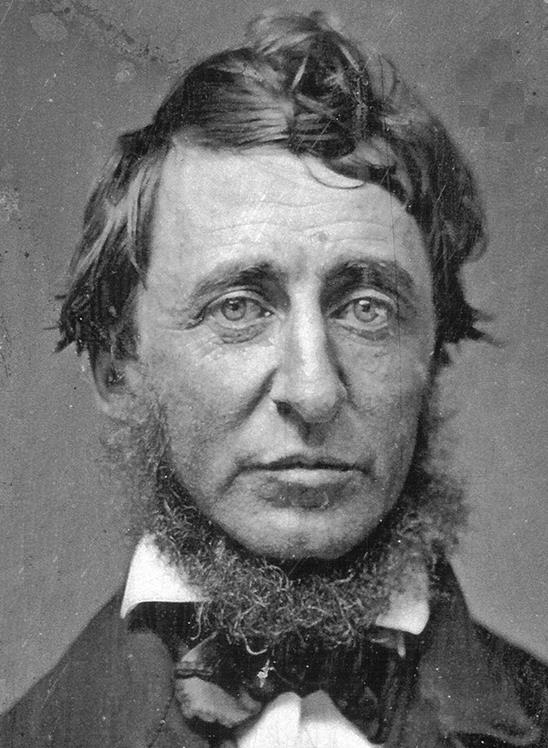

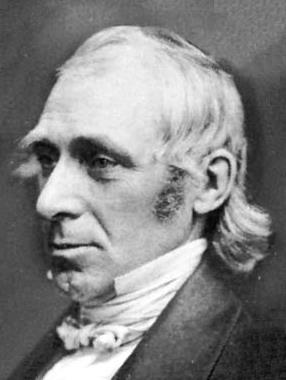

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Amos Bronson Alcott (father of novelist Louisa May Alcott) were neighbors in Concord, Massachusetts, who set the pace of Transcendentalism. Thoreau attempted to find serenity in two years (1845-1847) of relative isolation in the woods at Walden Pond, Alcott in his experimental school in Concord, and Emerson in his philosophical lectures and writings. Emerson, born in 1803, grew up as the second of five sons (two daughters and another son died in infancy) of a Unitarian minister William and his wife Rebecca. His father died when he was almost eight and he was raised by a circle of women, including an aunt with whom he would become very close. At age fourteen he entered Harvard College and graduated at age eighteen (surprisingly, only in the middle ranking of his class). He went to work with a brother, William, teaching young women at his mother's home. When William went off to Germany to study divinity, Emerson then established his own school. Several years later he himself entered Harvard Divinity School for study. In early 1829 he was ordained to the ministry at Boston's Second Church as its junior pastor. Then tragedy began to hit Emerson. In 1831 his young wife Ellen died of tuberculosis. Then a younger and very brilliant brother, Edward, who also had long been struggling with his health, both emotional and physical, died of the same disease in 1834. Finally another younger brother, Charles, died in 1836, also of tuberculosis. Emerson was devastated. Following his wife's death, he began to distance himself emotionally from traditional Christianity. The following year (1832) he resigned his position at the church to begin the search elsewhere for the answer to life's questions. At the end of that year he departed for a grand tour of Europe, where he would meet a number of such intellectual luminaries as the English philosopher John Stuart Mill and the Scottish lecturer and social commentator Thomas Carlyle. In Paris he would become intrigued by the botanical gardens of the Jardin des Plantes, where he hit upon the thought of how all things in life seemed mystically interconnected. Returning to America in October of 1833 he contemplated Carlyle's career as a lecturer, and the next month undertook the first of the 1,500 lectures he would offer over the next near-half century. These lectures would be his stock-in-trade, the source of a number of books he would publish. In 1835 he remarried (Lydia or Lidian) and they moved to Concord, where two sons and two daughters were born. Here, in company with three other scholars, the Transcendental Club was founded (1836) – with the hope of birthing a community similar to the salons of Europe where intellectuals would gather to discuss weighty matters of life. Among those who would join them was Thoreau, for whom Emerson took on something of a role as a father-figure. Emerson's split with Christianity became evident when in 1838 he delivered a lecture at Harvard Divinity School, affirming that Biblical miracles and the claim of Jesus' divinity were merely the inventions of the classic mind that assigned God-like qualities to their heroes. Emerson instead advocated something of a Humanism that freed the soul from the shackles of traditional religion so that it could soar in search of the higher meaning of life. Harvard Divinity School was scandalized by his bold Humanism (he would not be invited again to lecture there, until thirty years later when even Harvard Divinity School had begun to come around to holding many of Emerson's Humanist ideas). Efforts were made by Emerson's neighbor Alcott to put their organic philosophy into full operation as an experiment in communal living, when the entirely vegetarian farm Fruitlands was established. It was not a grand success. After it failed, Emerson purchased another farm for Alcott for a second attempt. He even purchased two sections of land for himself (though he himself did not work the land). As it turned out, the Transcendentalists were better at thinking, discussing, lecturing and publishing than at securing material success, although Emerson's lectures were beginning to pay well and his books were being widely read. Emerson now branched into esoteric or Universalistic study, taking up the study of Hindu Vedanta, reading the Bhagavad Gita and commentaries on the Vedas by Henry Thomas Colebrooke. His philosophy of the Oneness of Life had the larger religious confirmation of the Hindu religion. This fit his temperament better than traditional Christianity.

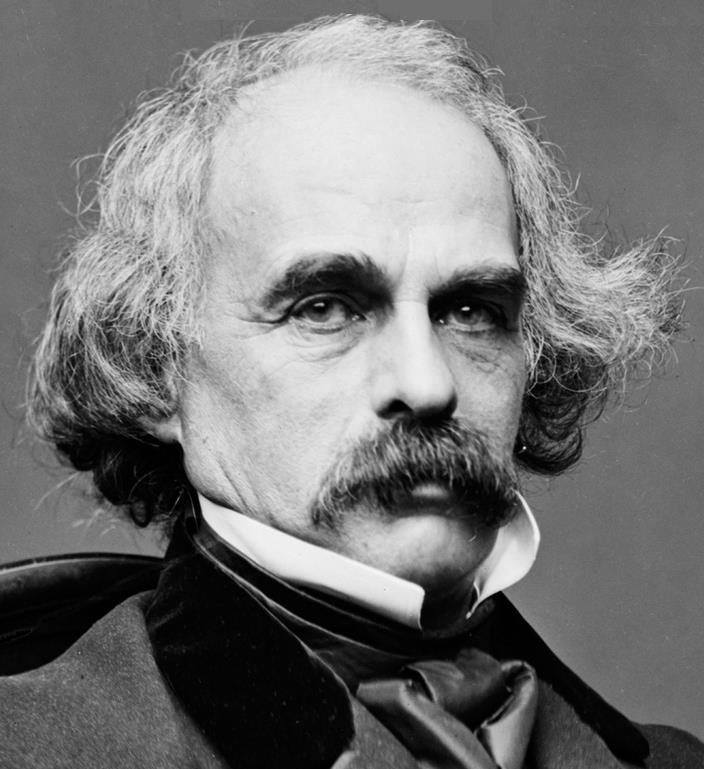

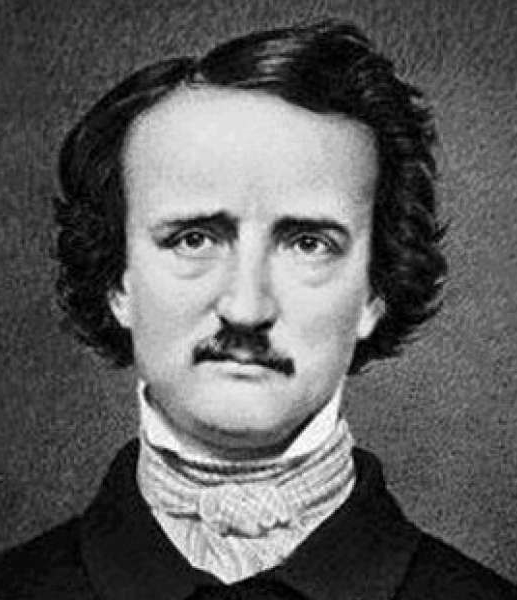

The earthier intelligentsia

Meanwhile, for those less comfortable, where life's dangers were not guaranteed to be manageable, where life could suddenly take a violent turn (hunger, disease, Indian massacre) such Humanist Rationality seemed as absurd as their personal trust in a God of miracles seemed absurd to the Humanists. Indeed, even Nathaniel Hawthorne, who once was a neighbor of the Concord Transcendentalists, eventually became something of an anti-Transcendentalist, tending to delve more into the darkness of the religious ethical issues of his era in his novels The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851). Likewise, Edgar Allan Poe could be just as abrasive in his dislike of the romantic optimism of Transcendentalism. There were also a number of other American writers and artists who represented well the life of the common man, the serene primitiveness of the American landscape and the exotic culture of the Indians, giving excellent characterization of the democratic realities of life in America. James Fenimore Cooper wrote elegantly of the complexities of life in America in such novels as The Pioneers (1823) and The Last of the Mohicans (1826). And in the field of graphic art, the works of Thomas Cole and others of the Hudson River School were on a parallel with the best of European landscape artists of the same era, as were the works of George Bingham who, in addition to his beautiful landscapes, portrayed insightfully democratic life in the Mississippi and Missouri River valleys. |

|

|

|

As far back as the 1790s, the first decade of the new Republic, it appeared as if Christianity might be resolving itself simply into a civic religion serving to provide a moral foundation and discipline for the emerging United States as a distinct society. Certainly that was how the intellectuals, especially the Deists among them (most all intellectuals at that point), understood things. But such civic religion did not fill churches, for it resided solely in the independent thinking and behavior of citizens as they went about their daily routines. It did not need pulpits to show the people how to go about doing such things. Human logic itself seemed pretty good at constructing such moral-intellectual systems. Part of this developing religious dynamic of Christianity as principally a civic religion was the result of the way that the war and the consequent independence of American society had a tremendous impact on the religious character of America. The Church of England, well beloved by the Tories particularly numerous in the American South, was devastated by the war. Eventually it was able to service Anglican loyalists in America by establishing its own Episcopal authority, and thus be able to carry on as before, but independent of England itself in doing so.5 As for the Calvinist Congregationalists in New England and Presbyterians in the Middle Colonies that had been active in leading the independence movement, post-war America had been expanding in population at a far greater rate than the slow process of producing seminary-trained pastors could meet the demand for new churches and individuals to pastor them. Also the very logical character of Congregationalist and Presbyterian theology, especially among the more highly educated of the membership (including, importantly, pastors), caused many to be quite comfortable in the Deist camp, leading some of them even to switch their loyalties to the growing (for the time being anyway) Unitarian movement. Baptists and Methodists however did not have this same problem, being open to the recruiting of lay pastors (not seminary trained but simply called out of general society to Christian ministry). These individuals had been led to take up their calls not by academic logic, but by a highly personal, and most frequently highly emotional, sense of personal judgment, moral cleansing and new purpose to their lives, a purpose calling them into full service to the very process that had personally saved them out of a world of sin. They were on fire to bring others to this same spiritual renewal or revival that they themselves had gone through personally. And they were willing to face all sorts of obstacles, both by nature and by man, in order to bring (especially to the frontier where churches were virtually non-existent) the gospel of salvation in Jesus Christ to hungry hearts there. This was not mere civic religion. This was religion of a very personal spiritual nature. Millennialism6 and perfectionism

Behind all this religious activity was something very much part of the spirit of the Jacksonian times. As Tocqueville had noticed, Americans had a strong sense of personal destiny, an urgency to accomplish some greater work, to move forward, to fulfill some nobler purpose in life. Life was viewed as a challenge, one faced with many obstacles, many of them deficiencies in the people themselves, personal deficiencies or sins that needed cleansing, ones that required some act of purification which would clear the way for them to gain some personal victory. Christian revivals offered exactly just such an opportunity for getting things right with God. Empowering this activity was an abiding sense that history was about to find completion in the form of the second coming of Christ and his final judgment of all people, saints and sinners, a widespread sentiment of the times due in part to the horrible 1837–1841 Depression which undercut severely the American belief that life moved forward along largely logical lines. Surely this grand catastrophe pointed to the ultimate and thus final judgment of God in the form of the long-awaited coming of Christ as the ultimate judge of life on earth. Consequently, many Americans came easily to the conclusion that they were approaching the millennium described in Scripture (Revelation) in which all must be made perfect in preparation for that final coming of Christ. Sinful behavior needed to be corrected, both for society as well as the individual. Perfectionism or social reform was thus urgent. The institution of slavery in particular needed to be abolished – immediately. Alcoholism, which was rampant on the Frontier and in the workshops back East, also needed to be curbed. Caring for the poor became a priority. Injustices of whatever variety needed to be addressed, the treatment of women being one of the issues taken up by a new generation of feminists. Social experiments accompanied this mood, in which varieties of utopian programs were put in place to answer the challenge of the times. Most of these failed miserably, but failure did not seem to discourage others from trying. Sadly, the quest for perfection usually set one group against another, even splitting groups time and again as perfectionists understood faults in the others, even small faults, to be the work of the devil in his attempt to stop the arrival of the millennium. It got confusing, and at times it became very bizarre in the routes such perfectionism took this rather primitive religious instinct so endearing to the American frontiersmen. But it made those simple souls, those who had moved to the frontier because their lives back East amounted to so little, now understand how special they were, even how royal they were, their purity of conscience bringing them into a very special relationship with God. On this sentiment they were very ready to build a new world. 5In the years between the 1st Great Awakening and America's war for independence, the Church of England's Society for the Propagation of the Gospel not only sought to bring the unchurched of America to Christ, but more importantly, it set out to bring non-Anglican Christians to leave their Congregational, Presbyterian, Quaker churches and join the Church of England, being far more active in setting up Anglican churches in coastal New England and the Middle Colonies than along the American frontier. As we have already noted, this assault on highly independent American Protestantism was another one of the ways that England had infuriated the colonies and driven them to want full independence from the mother country! 6A

belief that the coming of Christ will usher in a 1,000-year Golden Age,

a long period of time prior to the Day of Judgment, and the

establishment of a New Heaven and a New Earth.

|

|

Francis Asbury

The Methodist circuit riders

Also playing a key role in this development were the Methodist circuit riders, formed from that same adventurous spirit of the frontier culture, who had answered a call from God to head out alone on horseback into the Western wilderness. Here they faced storms, hunger and hostile Indians – to bring the comfort of the Christian religion to scattered settlements and cabins that dotted the wilderness. Their offerings were not just the assurance that God was with these settlers but that they were also somehow still connected with the rest of society, which was also with them. The way the circuit riders helped settlers to keep body and soul together was thus enormously appreciated on the Western frontier, where the Methodist church – or at least the Methodist movement – grew rapidly, soon to become the largest of the Christian denominations in America. By 1840 some 3,500 circuit riders and some nearly 6,000 pastors were supporting the faith of 750,000 Methodists! The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and AME Zion churches

The Methodists were officially opposed to slavery from the beginning of the denomination's entry onto the America scene in the 1760s. Asbury was hotly opposed to the practice, but learned that to reach Black audiences held in bondage as well as Whites, he would have to tone down his rhetoric on the subject. Otherwise he would send slaveholders off into fellowship with Baptists and Presbyterians, which at the time took no such position on the subject. But the Methodist position did not go unnoticed by free Blacks, and Methodism would have a tremendous impact in getting their Christian world organized and up and running. Richard Allen was a Black slave who was able to work to pay for his freedom from his Philadelphia master. In earlier years he had been very attentive to the Methodist circuit riders who had come to his plantation, and even before securing his freedom he had become active in encouraging fellow slaves with the gospel message. Once free he continued this activity, forming one small society and then another, until in 1816, in association with another free Black pastor, Daniel Coker, five newly developed congregations in Philadelphia were able to hold their first Methodist General Conference. Taking up the spiritual disciplines of Wesley's Methodists, they took the identity as the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, the beginning of what would eventually turn into another of one of America's larger denominations. Meanwhile in New York City in 1800

another group came together to form the Zion Church which grew

significantly, until in 1821 they were able to constitute themselves as

the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church under Bishop or

Superintendent James Varick. The AME Zion Church too spread across the

country among free Blacks. Both Methodist churches would compete in

eventually playing a leading role in shaping the religious lives of

newly freed slaves after the Civil War.

Camp meetings.

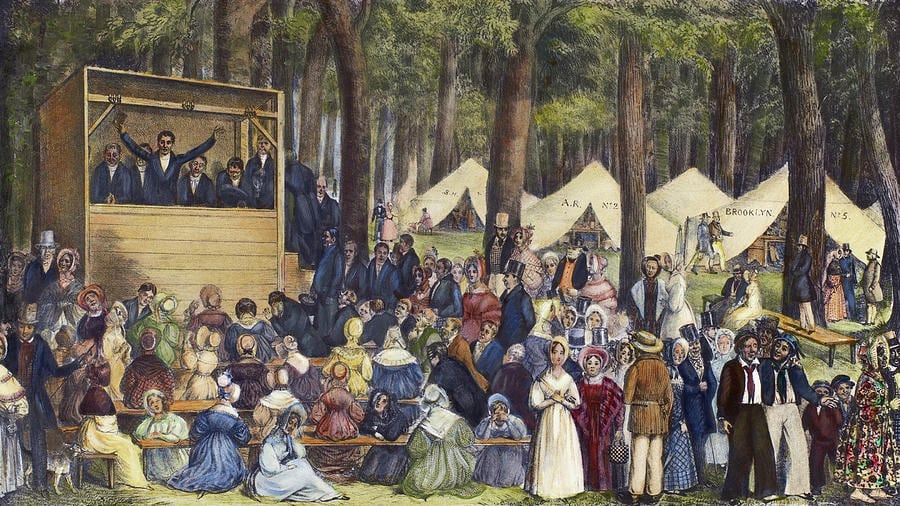

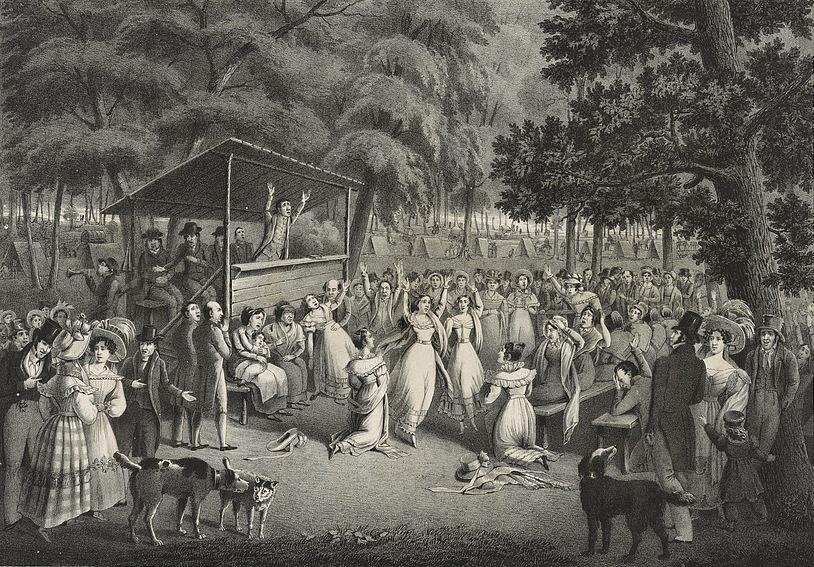

Meanwhile, off on the American frontier, the highly individualistic but also highly isolated life on the part of those Americans that lived well away from the comforts of the East produced among Westerners a hunger for personal meaning within the context of community, membership in larger society being a rare but well-appreciated commodity. Most frequently this took the form of huge gatherings whenever a local Christian revivalist appeared in the region. Thousands would turn out to spend a week at an improvised encampment listening to an array of preachers, singing and dancing, shouting and fainting, and having a thoroughly good time.

|

| In a day of declining spirituality, Finney developed a highly organized camp revival program which brought the gospel to the faithful in both upstate New York (the "burned-over district" Finney termed it ... because of the constant run of camp revivals there) and New York City. Others would copy his precise methodology. |

|

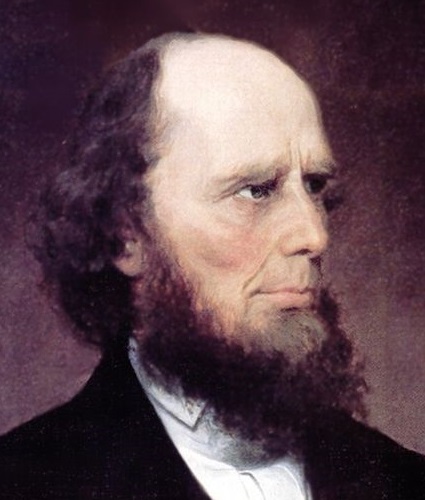

Finney

Taking a more structured (and thus "logical") approach to revivalism was the lawyer-turned-Presbyterian-minister Charles Grandison Finney. Though a Presbyterian, a denomination which traditionally viewed salvation as solely a matter of God's graceful election (and thus not really a personal work or achievement of man himself), Finney fit better the spirit of the Baptist and Methodist revivalists. He was required to appear before a Presbyterian board to examine his views on faith versus works, an issue which has caused considerable controversy since almost the founding of Christianity. In the end he satisfied the board that he preached a doctrine of grace rather than works, although his revivals' goal of cultivating immediate repentance and renewal had something of the quality of works before grace.7 His careful structuring of his revivals, taking place in the period 1825 to 1835 in both the rural setting of up-state New York and the urban setting of New York City, became a model that other revivalists would follow. It helped not only tone down (somewhat) the emotional level of these revivals, it also put them on steadier religious foundations. 7But this is a subject that no Christian has ever satisfactorily resolved by mere logic or precise theological argument!

|

|

Millerites and the Seventh-Day Adventists

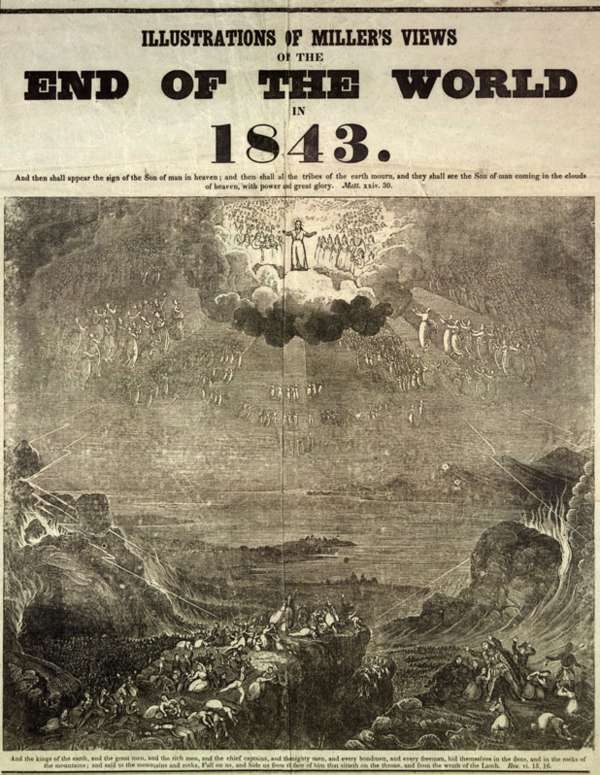

Another New York revivalist who played big on these instincts was the farmer and Baptist lay-preacher William Miller, who in 1833 predicted (on the basis of calculations he drew up from the Book of Daniel) that the long-awaited event of Jesus Christ's return to earth was going to take place sometime in the period 1843–1844, the accompanying rapture also ending life on this planet. His views began to gain wider acceptance as the 1840s loomed into view, his prophecy even taken up by followers in England, Norway and Chile. Ultimately in 1844 he and his followers gathered on hilltops and rooftops in March, again in April and finally in October in anticipation of the rapture. But instead a Great Disappointment occurred when Jesus failed to show up on schedule, causing his following to break up. Surprisingly, however, this was not the end of his massive religious movement. Others picked up Miller's vision (particularly its millennialist perspective), importantly the female prophet Ellen G. White, who cultivated a huge group of followers that would eventually take the name Seventh-Day Adventists. They took up perfectionist ways in the avoidance of alcohol, meat, and other foods, advocating instead vegetarianism. From this group would eventually come such famous breakfast food producers as Kellogg and Post.8 The Burned-over district9

One of the places that seemed to be particularly active in this new religious dynamic was the "burned-over district" of Western New York. Here wave after wave of millennialist revivals occurred, producing some of the most notable elements of the Second Great Awakening. The Millerites were very numerous in this region. Shakers were also numerous in this part of the state.10 The utopian Oneida Society was also established there to practice the idea of social communalism. 8Vegetarianism was a common trend among the millennialists, who believed that meat-eating made man a brutal beast. 9The term "burned-over district" was assigned by Finney to this region because it had held so many revivals that Finney was certain that there could be no one there left to convert. 10The

Shakers, as the Quakers before them, were noted for the shaking of

their bodies when they entered into a rapturous union with the Spirit

of God. They were notable also in that they believed that sex was

bestial behavior and thus they did not have offspring of their own,

forcing them to keep the community going through converts. Their

religion required all property to be held jointly; the equality of the

sexes; children (brought in from the outside world) belonging to the

whole community; the profits of workmanship shared communally, etc.

|

|

|

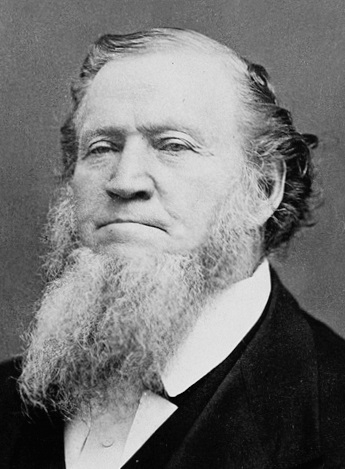

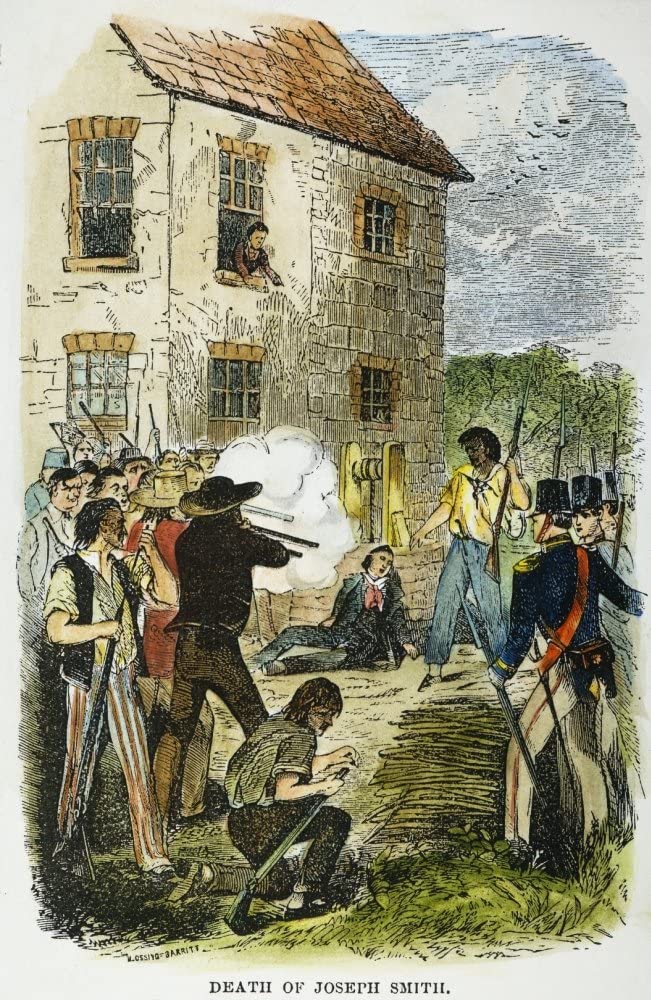

The Mormons

Certainly the most amazing phenomenon to come out of all this millennialism, and in this case even this same burned-over district of Western New York, were the Latter-day Saints or Mormons, a group that followed the prophecies and teachings of Joseph Smith, Jr. As a teenager, Smith claimed that he had a number of visions, the most important being a visit by the Angel Moroni in 1827, who directed him to a place where he reportedly uncovered a book of golden plates on which were written in some form of reformed Egyptian the story of the ancient Jews and of Christ and his visit to America. Using a special technique, he translated what he saw written there by ancient authors (Mormon being chief among them), which in 1830 Smith published in English translation as the Book of Mormon.11 That same year he formed his first congregation as the Church of Christ, teaching his followers the new doctrines, and then sending them west to spread the new revelation as Latter-day Saints. His ultimate goal was to establish a new Zion, a community of the Latter-day Saints, to prepare the way for the coming of Christ. At first he thought it would be in Ohio, where in 1831 a large group of his followers assembled. But then some of his followers moved on to Missouri, planning to establish his New Jerusalem or Zion there. But they ran into trouble when the local citizens reacted to the Mormons pouring into their area. Smith ran into the resistance of the local Missouri militia when he arrived in Missouri to try to secure the land for his followers, and thus he decided to build his temple in Ohio. But a major bank failure (resulting from the panic of 1837) undermined the harmony of his followers and Smith migrated with those who still remained with him back to Missouri. Once again he faced stiff resistance there, except this time organized by the governor of Missouri, who in 1838 was determined to drive the Mormons from his state. Thus some eight thousand Mormons followed Smith to Nauvoo, on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River. For the next few years he was able to proceed in the building of his temple, until the citizens of Illinois – seeing the land being overrun by these Mormons and shocked at the practice of polygamy taken up by Smith in 1843, a practice that seemed now so central to Mormon social organization – thus also began to take up arms against the Mormons. Then in June of 1844 Smith and his brother Hyrum were killed by an angry mob, throwing the Mormon community into confusion as to who was then to lead them. At this point a number of Smith's colleagues stepped forward to claim succession. Brigham Young took the lead, although other individuals also claimed the title and led their followers off to form their own separate Mormon communities. But after two years of trying to make things work out for them in Illinois, Young decided in 1846 to take his thirty-five wives and hundreds of followers West, all the way to the Utah territory in 1847 where they hoped to be able to build their community in peace. There indeed they found just such security – at least for a decade – and from there began to send out missionaries to the larger world around them, to build the new faith in anticipation of the coming millennium. 11The

book states that tribes of Israel (the Ten Lost Tribes?) had managed to

get themselves to the New World – as well as Jesus himself, who

appeared to the Indians soon after his Resurrection, producing several

centuries of exceptional peace among the Indians. Indeed, the book

claims that the Indians were in fact descendants of these migrating

Israelites.

|

|

|

New School versus Old School Christians

All of this highly emotional spiritual adventure impacting the young Republic was having the effect of splitting the old Calvinist religions (Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Dutch Reformed) between two camps: the New School group, supporting the revivalist trend, and the Old School group opposing it. Once again, similar to the earlier Great Awakening of the 1740s, the highly emotional character of these revivals seemed to Old School conservatives to be a most undignified way to bring people to Christ and also very shallow in how it might develop Christian life over the long-term in comparison to well-thought-through traditional Christian understanding. Worse, New School revivalism seemed to support the Arminian (or Methodist) idea that man was somehow able on his own to rise above his state of moral or self-focused depravity and elect or choose entirely on his own his personal salvation. Also, of course, the very idea that a person was not properly aligned with God without having one of these highly emotional moments of conversion seemed highly offensive to those raised since their youth to follow the lines of the faith as best as they could, understanding that they were indeed sinners, but always throughout their lives as faithful Christians sensitive to the need to keep themselves open to the judgments of God. For this latter group of Old School or Christian conservatives the suggestion that the path they were on was not sufficient because it had never arrived at an emotional crisis point of decision was outrageously ridiculous. Christian mission societies

However, the Second Great Awakening did not in fact somehow leave the Old School churches out of the religious developments of the early 1800s. On the contrary, there were some very significant developments that took place among these older denominations. Although they did not take on the colorful features of New School revivalism, they went a long way in developing the religious character of the young Republic. What is being described here is the birth in the 1810s and 1820s of a large number of interdenominational Christian societies that sought to set Christianity to the task of taking on a number of social problems, blemishes that embarrassed good Christians. These Old School Christians also believed strongly that America had a vital role to play as a model of Christian virtue to the larger world. These new societies were thus set up to provide Christian demonstrations as to how such issues as poverty, illiteracy, and just plain ignorance of the Christian gospel were to be taken on by the faithful. Working across denominational lines (Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed, etc.), Americans were very active in forming such groups as the American Bible Society (to help every American family find itself in possession of a Bible), the American Sunday School Union (to develop Biblical literacy among the children of all social classes), the American Tract Society (to put in the hands of everyone the simplest explanation of and call to Christianity), the American Anti-Slavery Society, and the American Temperance League (both fighting particular social evils). Then there was the inter-faith (Congregational, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed) American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABDFM) created in 1810, which sent missionaries to the Cherokee (and other American Indians) and ultimately overseas to Hawaii, China, India, the Middle East and finally Africa. These volunteer organizations became a vital part of the American social-cultural dynamic that developed in accompaniment with America's spread across the North American continent, and soon across the world. Christian colleges

Christian colleges. As we have already noted, from the time of the Puritans' early settlement in America, higher education was a matter of vital necessity, not only in training the pastors who would be expected to lead the Christian communities the Puritans were establishing but in training in other areas such as the law, business, finance, and teacher training – all so vital to the life of their communities. Thus Christian America founded Harvard, Yale, William and Mary, King's (Columbia), Georgetown, the College of New Jersey (Princeton), New Brunswick and Andover Theological Seminaries, as well as colleges such as Mount Holyoke, designed to give women the same opportunity at a higher education. In fact, in the period between the founding of the colonies and the mid–1800s, over 500 colleges were founded by America's various denominations. This too was a key part of Christian America's larger mission to be a Light to the Nations. Horace Bushnell

And then there was the compelling voice of a Connecticut pastor calling for interdenominational compromise, a spirit of Christian unity ... and in doing so would greatly impact his times (and continue to do so even through the rest of the 1800s): the persuasive voice of Horace Bushnell. He took a unique position that aligned him exactly with none of the contending Christian groups, yet found value in all of them. With respect to the Old School Christians, he was quite respectful of the way traditional Calvinist Christianity was able to shape from a person's very early life, even childhood, key Christian understandings that helped direct a person (elected purely by the grace of God to the privilege of being born into full Christian fellowship of Christian family and church) toward a long-term and deeply faithful Christian life. This understanding was clearly laid out in his very popular book, Christian Nurture (1847). At the same time, he was highly supportive of the Unitarian (and Arminian or Wesleyan or Methodist) viewpoint that man did have the responsibility (and thus the choice in the matter) of disciplining or ordering his own thoughts and actions as part of the mature Christian life. And for a period of time he was quite supportive of the Transcendentalists' mystical approach to God, seeing such a higher reach of the soul as vital to a strong personal relationship with God. However, in early 1848 he found himself decisively back in the support of the idea of God, not in the form of the Transcendentalists' Universalist Deity, but rather in the traditional Trinitarian view of God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. But even in this retreat, he continued to believe that although emotional revivalism was not necessary for everyone to reach God, it certainly served very well those who had become quite lost in their journey in life and was an authentic way of bringing such lost but spiritually hungry souls to Christ – provided that such revival always was followed up by on-going fellowship with a worshiping community, in order to make the salvation-event a lasting transformation. Although he would draw criticism from all the communities for his less than full embrace of their respective positions, his ability to see Christianity above these divisions would come to be of great value to American Christianity in the days ahead.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges