|

|

The widening social-cultural gap between the North and the South The widening social-cultural gap between the North and the South The North The North The South The South The Compromise of 1850 The Compromise of 1850 Glimpses of mid-century life in America Glimpses of mid-century life in AmericaThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 266-273. |

|

|

Behind the moral-legal battle in Congress, in the press, and in the pulpit stood a stark social reality that was forcing both North and South into ever more inflexible positions as the two sections of the country faced each other. A big part of the problem was of course the slavery issue. But there were other issues that were pushing the two sections of the country further and further apart – also in part related to the slavery issue but more importantly related to the way that the social-cultural dynamics of the two regions (with the young West beginning to form a third part of the social-cultural distinction) were rapidly unfolding. Both key sections of the country were heading down very different socio-economic paths. This would only add to the inability of the two main sections of the country to understand or even just work with each other.

|

|

|

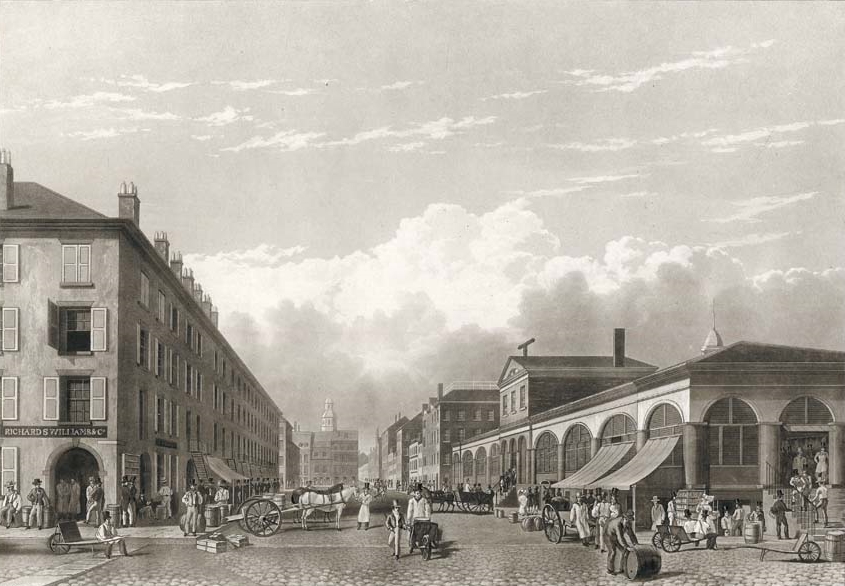

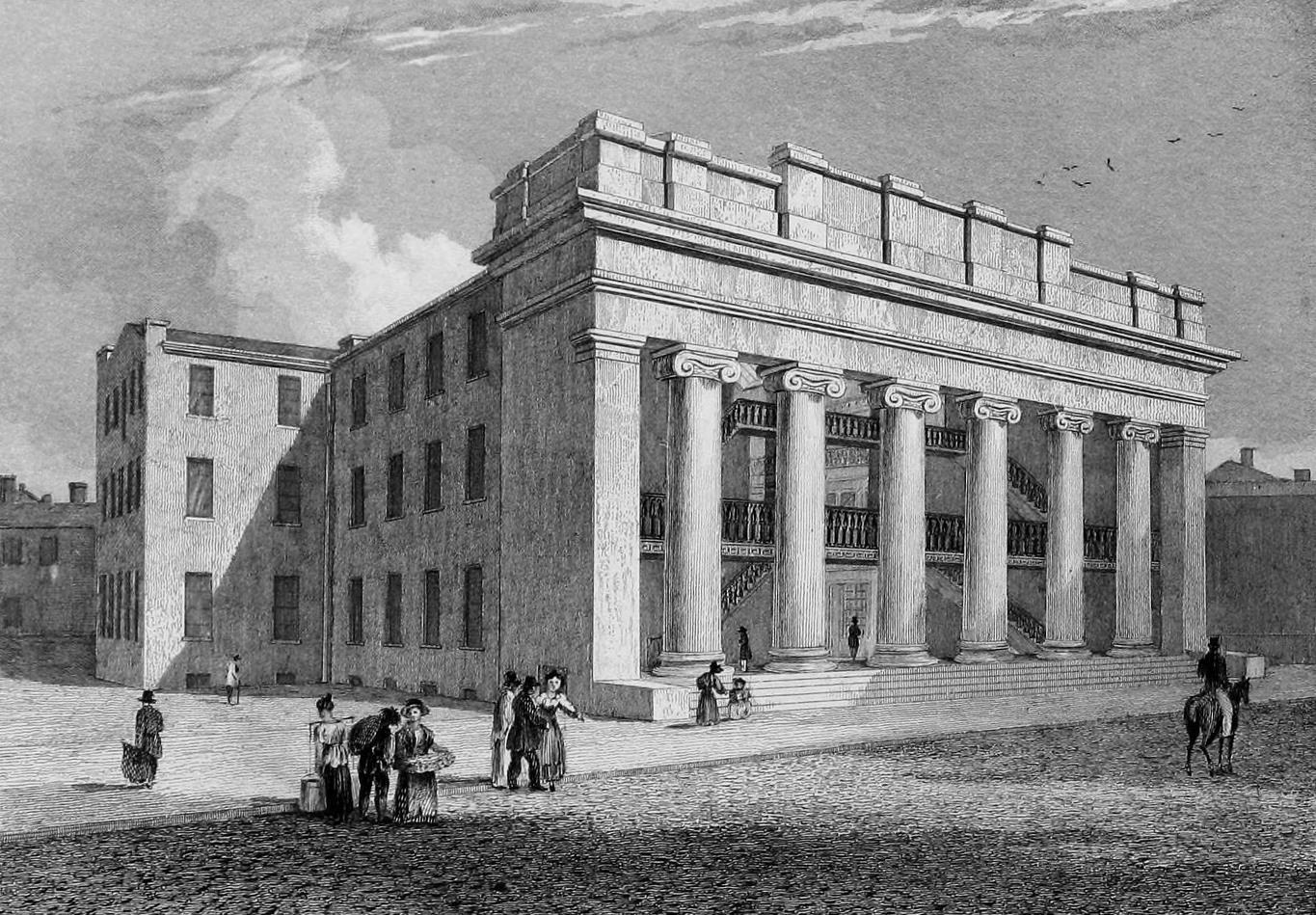

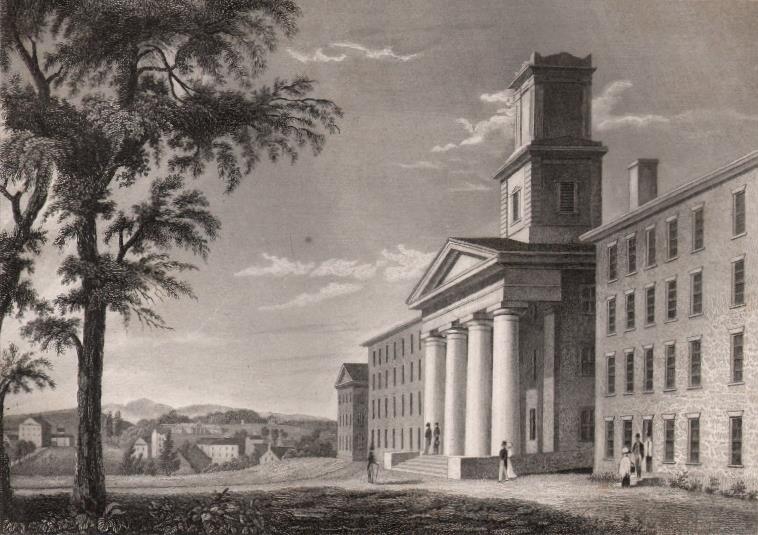

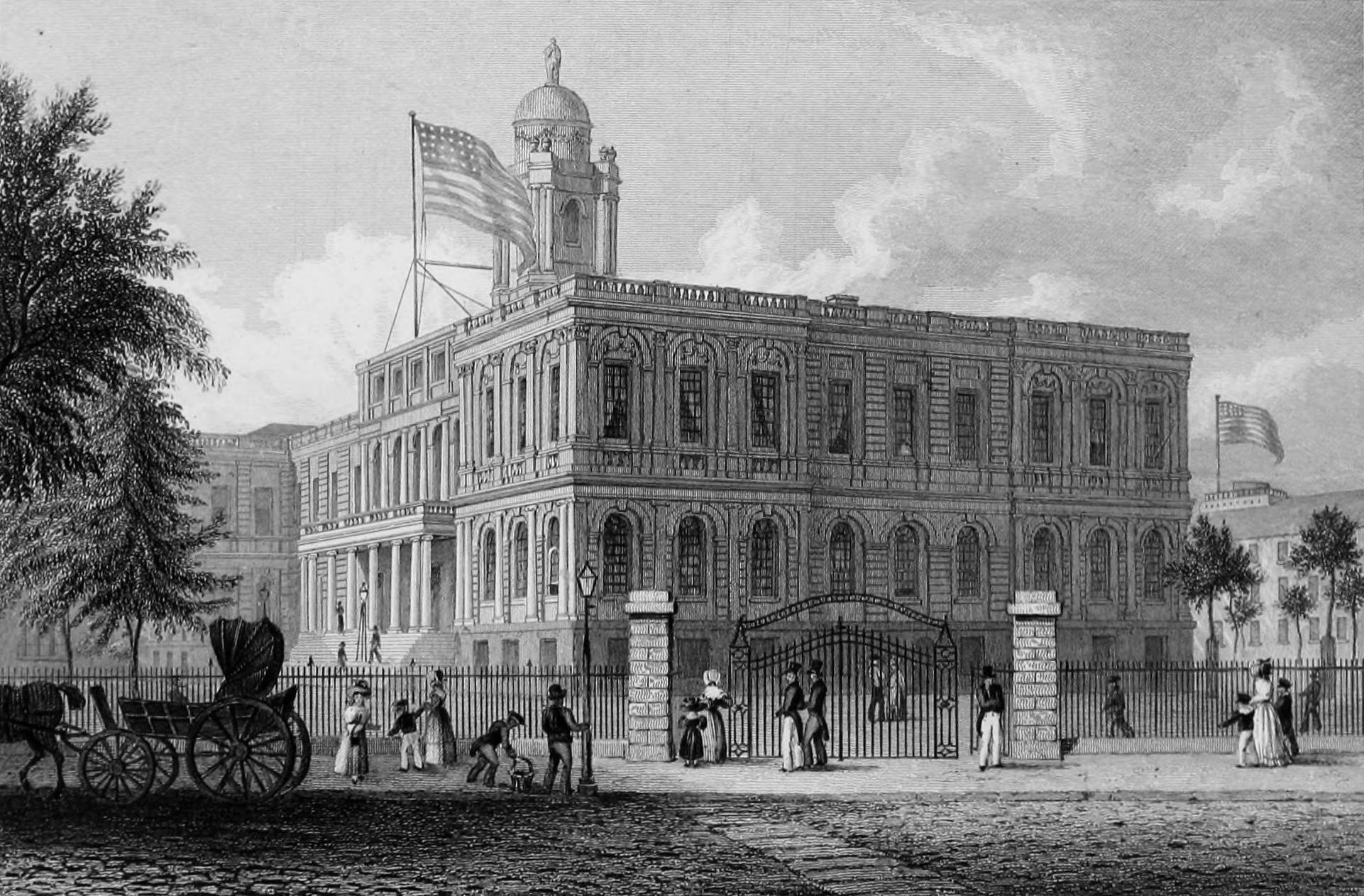

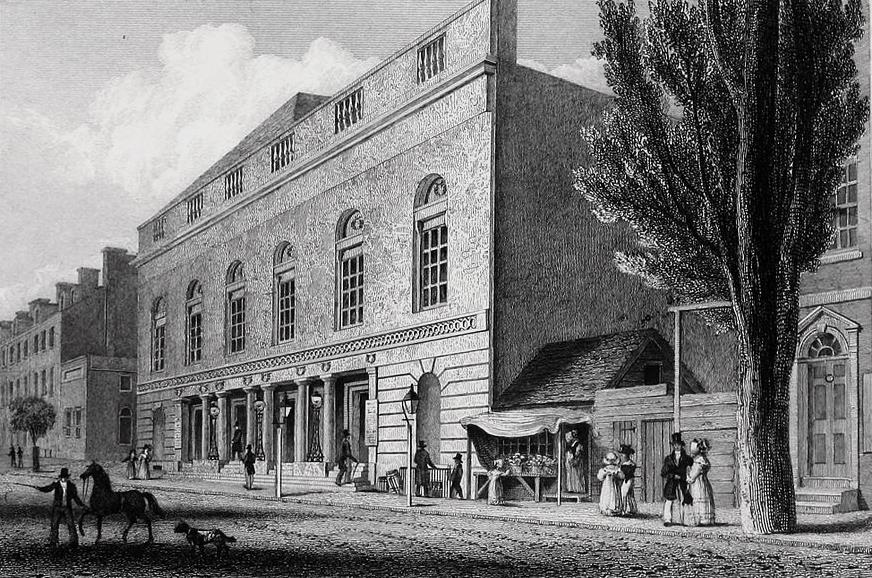

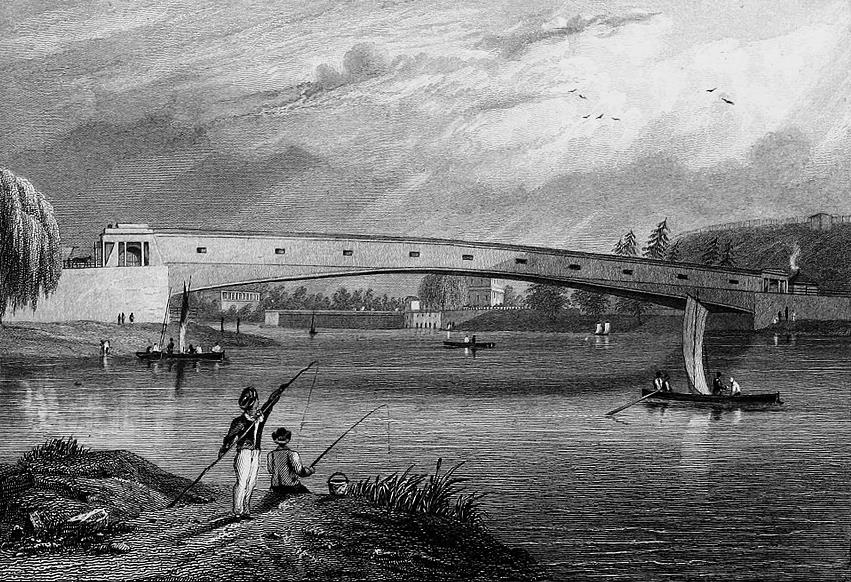

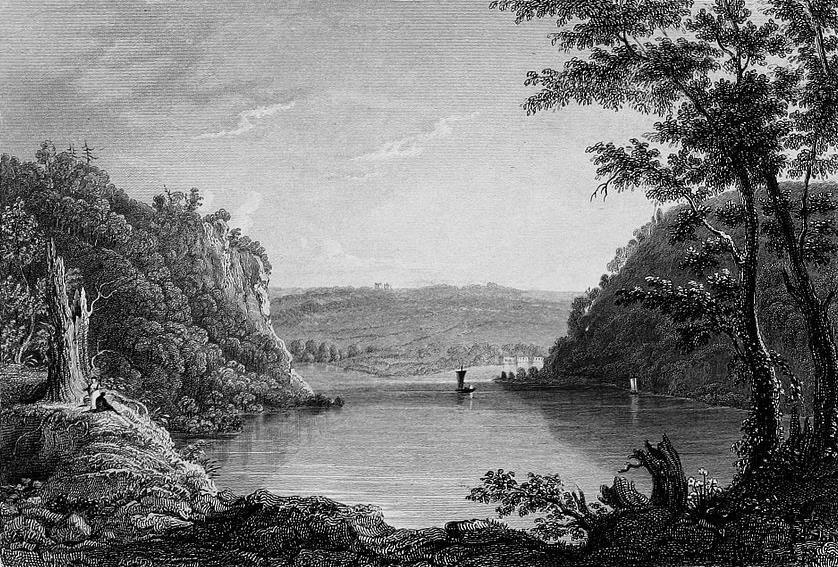

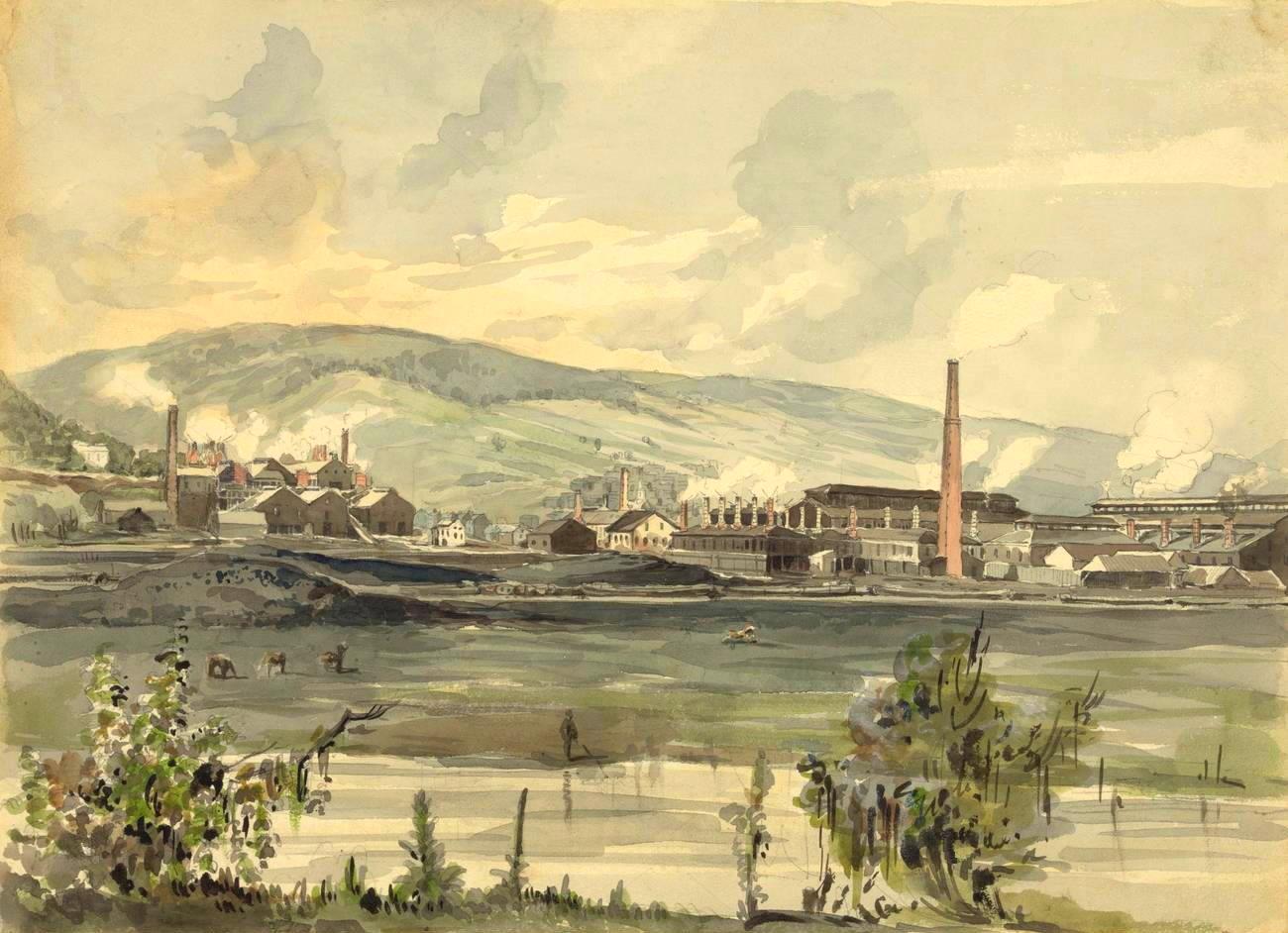

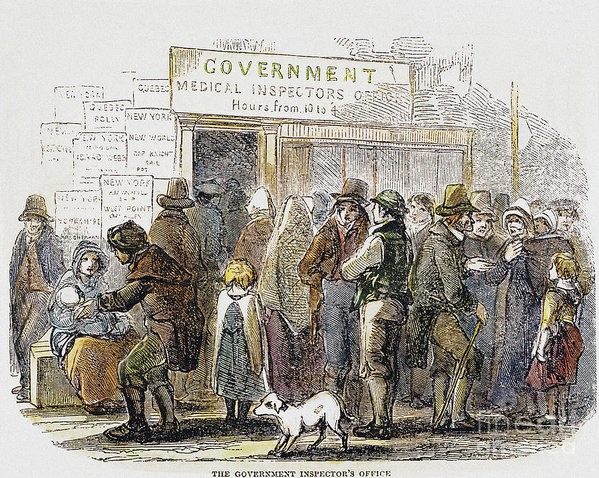

The North was prospering in a way that the South, despite all its romantic ideas of the elegance of Southern plantation life, could not match in terms of economic achievement. An observer of life in the North would have been quick to note all the infrastructure recently completed or under construction in the North: roads, canals and railroads. True, these were also developing in the South, but at a much slower rate than in the North. For each mile of track laid out for railroads in the South, three miles were being constructed in the North. And even at that, the Northern lines tended to run East and West linking the industrial East closely with the expanding Western frontier. Comparatively few of the roads ran north and south to link more closely the Northern half of the country with the South. The coastal cities of the North (Boston, New York, Philadelphia and even Baltimore) were bustling with new life, much of it from European immigrants – who knew of the lack of economic opportunity in the American South and thus headed from Europe to America's Northern coastal cities. Much of this new life coming to the North was chaotic, fueled by a mass of Irish coming in from Ireland to escape the horrible 1840s potato famine which was devastating their country. The Irish came to all of the major cities of the North (but also the rather Catholic New Orleans in the South), disrupting the calm composure of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) America with their Irish Catholicism and defiant Irish attitudes (they disliked the Anglo world intensely for the highhanded ways the English had dealt with the Irish crisis). Under the impetus of this Irish invasion, New York City, for instance, became a very vibrant but also a rough place in which to live and do business, with its tough neighborhoods, its Irish gangs, and its corrupt political wheeling and dealing. To the Irish, as would also be the case for the Southern Italians and Sicilians who would flock to the country early in the next century, social justice or law had little to do with abstract Constitutional principles and political offices developed in the long English tradition of both England and America. Instead, they saw justice as vested in local urban bosses whose job in government was to use the public treasury to take care of their own people. This Irish paternalism was something the WASPs called corruption, but something the Irish instead looked upon as being simply what any person had the right to expect from government. Further West into the heartland of the American North were a large number of prosperous towns and cities – large and small – and a multitude of small and well-kept farms dotting the Northern landscape, from upstate New York and Pennsylvania in the East to the fields of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Kansas in the West. All of this seemed to evidence solid success, even if only on a small scale. There was a sense of inventiveness, of activity, of progress, of confidence, of accomplishment, energizing the average Northerner, who looked with pride on his or her work in the home, in the field, in the shop. Here too immigrants added to this picture of vitality, notably the Germans and Scandinavians, who however blended into the American Midwestern landscape more readily than did the Irish in the American urban East. These northern Europeans were a more communal group, especially the Mennonites and the Amish among them, with a communal work ethic in many ways even more rigorous than the highly individualistic Yankee work ethic of the Anglo North. Very obvious material success followed their efforts, adding considerably to the picture of rural prosperity in the North. With the opening of the West all the way to California, the Northern pattern tended to be the one that reached into the new western territories. There were slaves that accompanied some of the White newcomers to the West, though they constituted only a small part of the population that crowded West to lay claim to the new land. Slavery was not very useful in terms of the types of challenges these newcomers faced in the new West. Indeed, frontiersmen were very much the same individualists as the American Northerners, depending on their own talents to survive and prosper in a highly competitive world.

|

|

|

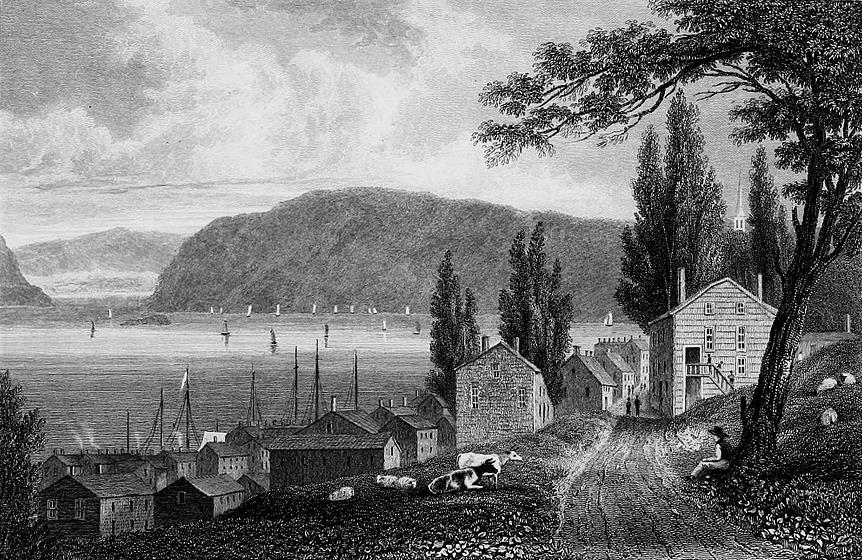

The South could easily sense that the social dynamics of a rapidly growing America were not going its way. A mood of defensiveness was settling in on the South, still proud of its own distinct cultural traditions – and the peculiar institution of slavery that Southerners understood as constituting the foundation of it all. The more the North pressed them on this matter of slavery the more defensive they became in asserting the correctness of Southern social values. But sadly, despite all the romantic swooning about the aristocratic plantation life in the rural South, the material reality was not quite so elegant. To be sure there were endless rounds of social visits (in the style of the British aristocracy that Southerners attempted to duplicate), fancy balls, fox hunts, etc. to occupy the privileged members of the plantation class. But behind this pleasant façade stood a troubled reality. All of this style stood on very shaky economic ground. Cotton was king in the South, so much so that for a long time there had been little interest in the production of anything else. The amount of cotton that was produced was truly vast, which meant that the price per bale produced would remain competitively low. And it would reach an even lower low when cotton production from India began to hit the world market. The plantations, despite all the flow of cotton from their vast fields, were stretched greatly to make an adequate profit able to sustain this luxurious lifestyle. Urban life of course existed in the South, but not generally of the bustling industrial variety found in the North. Urban life was largely an extension of the all-prevailing cotton economy. Towns such as Richmond, Columbus and Atlanta existed mostly to collect and market the cotton of the rural areas immediately around them (plus buy and sell slaves as an accompanying activity). On the Atlantic and Gulf coasts cities such as Baltimore, Charleston, Savannah, Mobile and New Orleans1 served as points of departure in the shipment of cotton to both British and New England textile mills. Beyond cotton, the South was slow in its uptake of the new industrial revolution. Steel was manufactured in the South as well as the new tools and equipment to aid the economy of the Cotton South, but not at the rate that it was being produced in the North. Nonetheless, despite the smaller scale of the industrial revolution in the South, rather substantial profits were to be had by those who ventured into the competitive world of industry. Yet, the status and prestige that Southerners sought was not assigned by Southern culture to the world of capitalism. It belonged largely to the romanticized world of the rural plantation. This was what truly slowed the South in its economic development, at least in comparison to the rapid industrial growth of the North. Worse, no industrial invention had provided an alternative to the hard reality that cotton was still picked by hand. Cotton picking or chopping was a painful finger-bleeding and exhausting back-breaking labor as well as often a spirit- breaking activity, especially when accompanied by the whip of a White overseer who had the responsibility of making sure that the Black slaves under his charge met high-reaching production quotas. Cotton farming did not make for much happiness, not just for the slave but also for the White farmer who could not afford slaves – as indeed the vast majority could not. The Southern dirt farmer was by economic reality reduced to a material standard of living hardly better than that of the slave, often occupying shacks no more comfortable than the ones the slaves occupied on the plantations. Of course the White farmer was free and the Black slave was not. And on that difference the poor-White farmer staked his entire self-image, to ensure that at least that small achievement would not be taken from him by freeing the slaves and thus putting him on a par with them. To protect that slim social distinction, he would be willing to fight fiercely. Beyond that he dreamed the Cinderella dream that he someday might find himself elevated to the social level of the plantation elite whom he admired greatly (when he was not resenting them). The dream sustained him somehow, even though there was virtually no likelihood of it ever coming true. As for the slaves, the tragedy of the lives of the masses of these captive workers was almost beyond endurance. It was not just that they were worked to exhaustion daily but that they had no sense of the future ever holding anything positive for them. In fact the future held the agonizing possibility of their much-loved spouses or children being taken from them by a cash-strapped owner who needed to sell them to pay off mounting debts. They were treated like commodities, similar to cattle, and even bred like cattle in order to build up their numbers as an economic asset, averaging in value at that time around $1000 apiece if they were young, strong and of a fertile age. And of course there were the young masters who could not keep their hands off of attractive female slaves, humiliating both slaves and White family at home with their sexual adventures, which no one dared talk about even though it was widely practiced. And connecting the slave and the slave owner besides the whip was the regime of fear produced by the whip. Although to ease its conscience White society attempted to dehumanize the African slave, there was no way that the Whites could get past the understanding of exactly how the slaves must truly feel about their White masters. That link of fear was based heavily on the constant concern about the possibility of a slave rebellion (such as the successful slave rebellion in Haiti or the failed one of Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831). The White South did not know what to do. To keep the slaves in submission they would have to be unflinching in their harsh discipline, which they knew darkened ever deeper the slave heart. Yet to try to win slave hearts was to have to release that grip, which could then explode the very social foundations of the South.2 1New Orleans was actually the third largest city in America at the time. Being the primary port of the huge Mississippi River watershed region, its economy was much broader, of course, than just the cotton trade. 2White

Southerners were keenly aware of what had occurred in the French colony

of Haiti in which in 1791 the African slaves successfully rose up

against their French masters, defeated an effort in 1803 by Napoleon's

military to bring the slaves back into submission and ultimately in

1804 butchered thousands of French, forcing the French to finally

acknowledge the obvious: Haiti was free of White oppression.

|

|

|

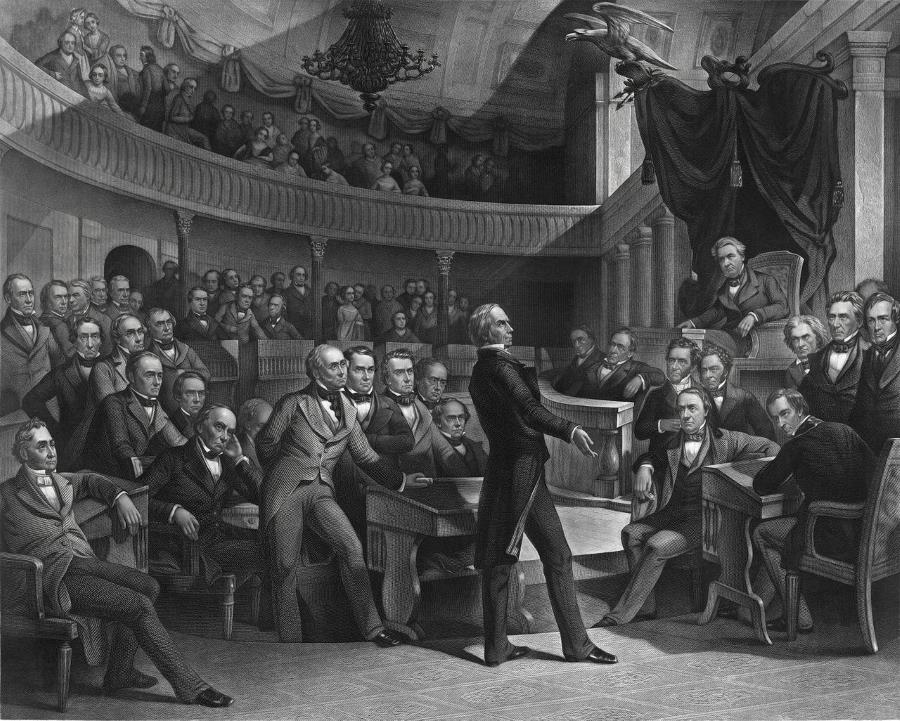

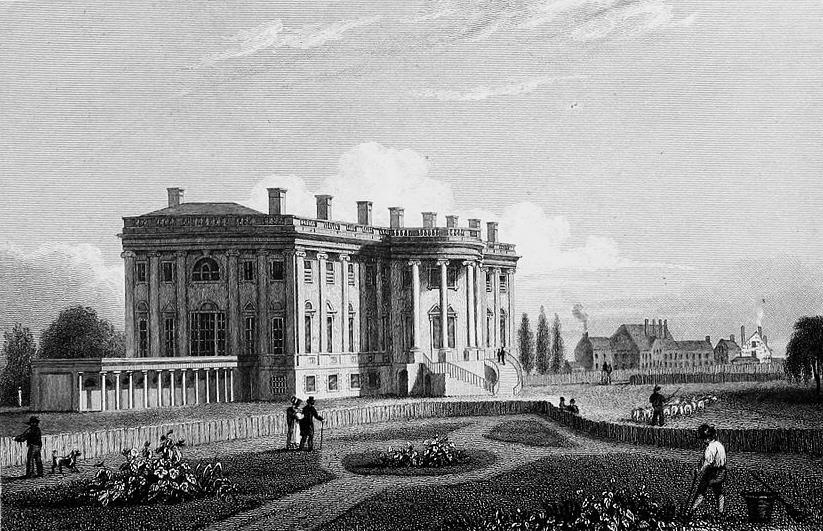

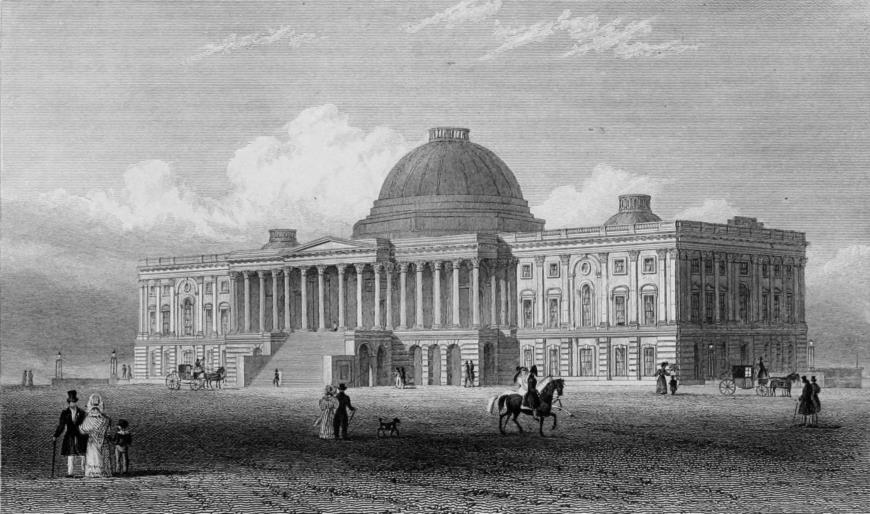

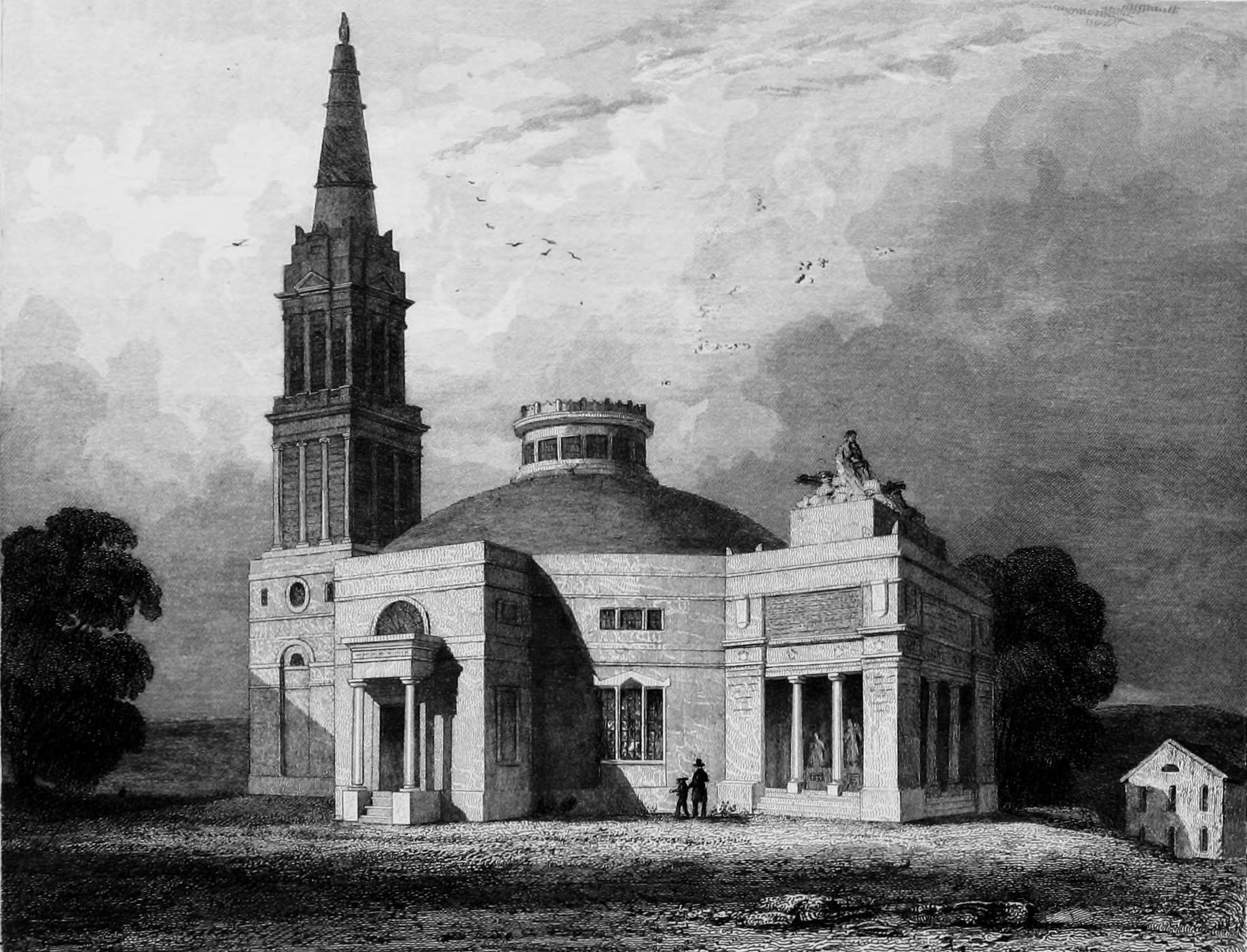

The Compromise of 1850

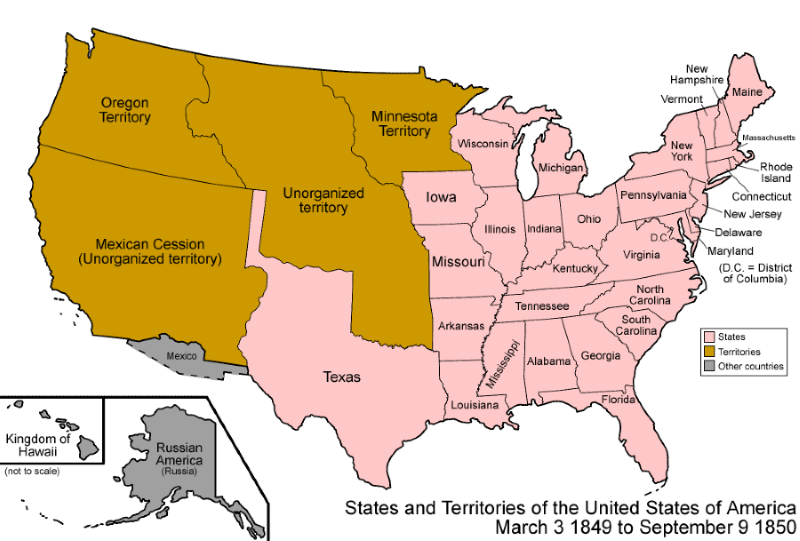

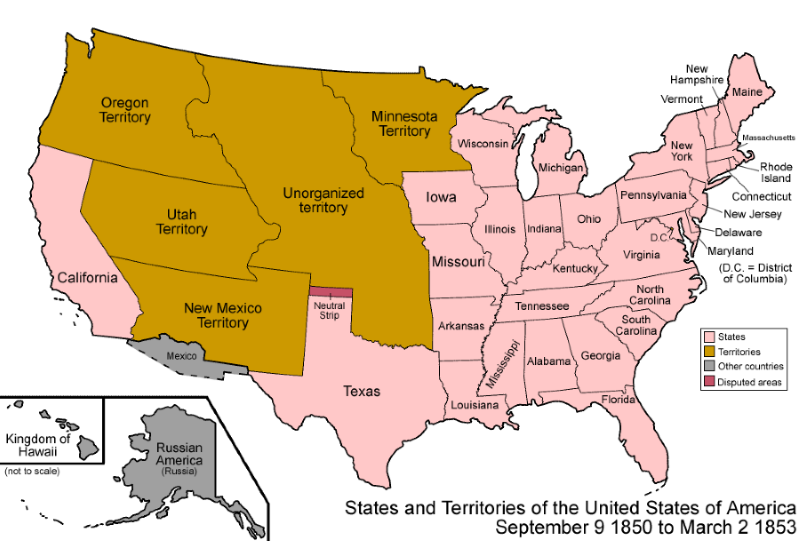

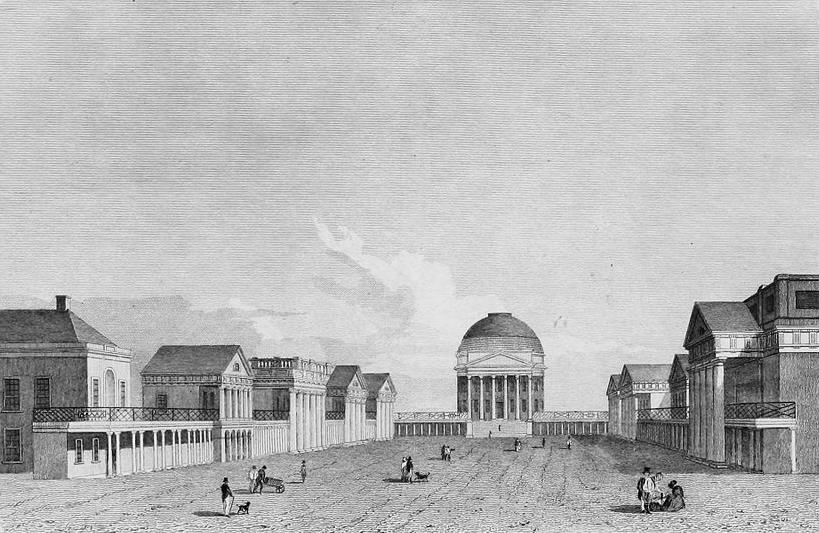

The American acquisition of the Western territories resulting from the Mexican-American War had sadly and even tragically merely presented another round in the North-South contention over slavery and its extension westward. Promoted strongly by former General and now President Zachary Taylor was the idea that California, New Mexico and Utah should be brought directly into union with the U.S., and not go through the stage of first being territories prior to statehood. Furthermore all three future states had expressed the intention of being brought into the Union as Free-Soil states. This was not going to please the South. At the same time, Southerners were already talking about disunion. In late 1849 Mississippi called for Southern representatives to meet the following year in Nashville. The purpose of this meeting though unstated was obvious. They were going to be gathering to discuss this very possibility. Needless to say, all this created quite a stir in Washington. When the candidacy of California was put forward for statehood at the very end of 1849 tempers in Congress flared. California was going to be admitted as a free state, ending the tradition of maintaining a balance in the number of slave and free states. The speeches for and against grew hotter as they took on very biting moral accusations and moral justifications concerning the central issue of slavery. One vote followed another as the two sides deadlocked over the issue. Once again the Great Compromiser Henry Clay (but now also a very weak old man) stepped forward in the Senate3 at the end of January (1850) to offer a set of proposals that he hoped would smooth feelings on both sides, and ease the way for California to achieve full statehood. The bill authorized the admission of California to the Union as a Free-Soil state; it set the Western boundaries of Texas, thus ending the contention Texas had with New Mexico; it designated both Utah and New Mexico as territories, with each possessing the right to determine how they would eventually enter the Union, as free or slave states; it called for the end of slave sales within the Washington, D.C. capital (though not the end of slavery itself in the nation's capital); it required Congress to drop any claim of authority to regulate the interstate trade in slaves; and it required the North to return escaped slaves to their owners in the South, a measure that was designed to calm the fears of the South about Northern Abolitionist ambitions. As compromises typically fare, it pleased the moderates of both the North and the South but also succeeding in angering the extreme wings of the Abolitionist Northerners and increasingly independence-minded Southerners. Particularly upset were the Northern Abolitionists to whom the idea of the forced return of slaves that had escaped to the North was an abominable idea. They would have none of it, even if it meant defying the nation's laws. But not everyone in the South was appeased by this compromise either. At the beginning of March, Calhoun, too weak to deliver his speech himself to the Senate, had someone read for him the biting accusations about the rising tyranny of the North, and his call for an amendment to the Constitution that would give the nation a dual presidency and the right of each state to veto any act of Congress. Also, Southerners should be able to go anywhere in the Union without the fear of having their property confiscated. Slavery must be protected throughout the Union. Anything less than that would be answered with the secession of the Southern states. The speech shocked everyone, yet had the effect of emphasizing even more the importance of compromise in order to save the Union from dissolution.4 Several days later it was the turn of the third elderly member of the Great Triumvirate, Daniel Webster, to address the issue in the Senate. In his three-hour speech, he recalled the history of the slavery issue as it had taken on ever greater importance to the nation, the efforts to bring the issue to compromise, and the overriding importance of maintaining the Union. He also projected that any move to disunion would throw America into chaos, and ultimately murderous conflict. With this he was stating what was becoming increasingly obvious to all, that if America continued to behave as it had been recently, there would be no escaping some horribly violent outcome. The nation had to come together. Then four days after Webster's speech, it was the turn of a rising star within the Senate, William Seward of New York, an Abolitionist Whig, to be heard. He put forward the claim that there was a higher law than even the Constitution that he answered to, the Law of God. That higher law would never permit him to return an escaped slave back into the arms of immoral, illegal servitude. Southerners were furious. Even Northerners were stunned. But Seward had laid the seeds of an argument that would gather force among the Northerners. A Congressional committee was set up to consider Clay's proposals and finally in May these proposals were brought before Congress in the form of an omnibus5 bill: all measures to be voted up or down jointly in a single vote. Meanwhile tensions were growing between (slavery) Texas and (free) New Mexico, as Texas claimed that the eastern half of what was being designated as New Mexico territory was in fact an integral part of Texas. Texas was willing to enforce that claim by military action if necessary. But President Taylor weighed in against Texas and demanded immediate accession of New Mexico as a new state, and as an old soldier was willing also to enforce his viewpoint by military action if necessary. Southerners then were quick to join Texas in their outrage over this move by the president because the accession of New Mexico would mean one more free state being added to the Union. War clouds began to gather in the West. Then in the midst of the furor, President Taylor got sick attending a long, hot 4th of July ceremony in the capital, worsened (by the help of doctors who bled him extensively and pumped him with narcotics), and died five days later. The nation was stunned.6 But this automatically elevated Vice President Millard Fillmore to the presidency. And he was willing to take a more centrist position, consulting both Clay and Webster, both well known as willing to compromise on this matter. But at this point it was time for yet another key figure to take center-stage: Illinois Democrat Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Though Douglas was a major slave owner (thanks to his wife's inheritance of a 2500-acre plantation in Mississippi, which he rarely visited but which was for him a constant source of revenue) he was a Democratic Party moderate on the slavery issue. He proposed that the various portions of the omnibus bill be broken out into their different parts and be considered separately. This lowered the tension about the all-or-nothing character of the legislation. Also with the radical pro-slavery Calhoun

gone from the scene and with the death of the strongly Free-Soil Taylor

also no longer in the picture, tensions eased. Talk of war subsided.

Now a new mood opened the opportunity for compromise. An exhausted Clay called on Stephen Douglas to run his measure through the Senate again. This time the Compromise made its way successfully through Congress in September in the form of a number of pieces of legislation. Texas was willing to give up its claim on New Mexico (and adjust its territorial boundaries elsewhere as well) with the assumption of $10 million in Texas debt by the federal government. And the part that the Abolitionists hated so fiercely, the promise of the North to return all escaped slaves to the South (coupled with massive fines slapped on anyone aiding and abetting any escape of a slave), was finally passed as the Fugitive Slave Act. Now the thought arose that the slavery issue had been resolved once and for all. The Union was saved. But Southerners remained skeptical. To them, whether the Union held or not depended on how faithfully the North enforced the Fugitive Slave Act. They were soon to find out. 3Of course both houses of Congress were debating the same issue, but the nation's eyes tended to be turned more to the Senate where debate was viewed as having more of a strategic nature, especially when it involved an address to the Senate of one or another of the Great Triumvirate of Senators Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun. 4John C. Calhoun died some four weeks later. With Calhoun dead, the Nashville conference got put aside, and the secessionist mood in the South subsided, for a while anyway. 5This was a term that Taylor came up with, unhappy at how all these measures had been thrown together, like being put in an omnibus, a large city carriage that anyone could ride for a fee. The term stuck and is now used regularly in Congressional legislation. 6Rumors

persist to this day that Taylor may have been poisoned. In 1991 tests

were made that said no, but even the tests have been contested.

|

|

George Caleb Bingham – The County Election (1852)

oil on canvas

Saint Louis Art Museum

George Caleb Bingham

– The Boatmen

Saint Louis Art Museum

1850 – Irish Immigrants

Go on to the next section: The Steps towards War

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges