|

Lincoln's early years Lincoln's early years The 1860 elections The 1860 elections The "Team of Rivals" The "Team of Rivals"  The war president The war president The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 285-289. |

|

|

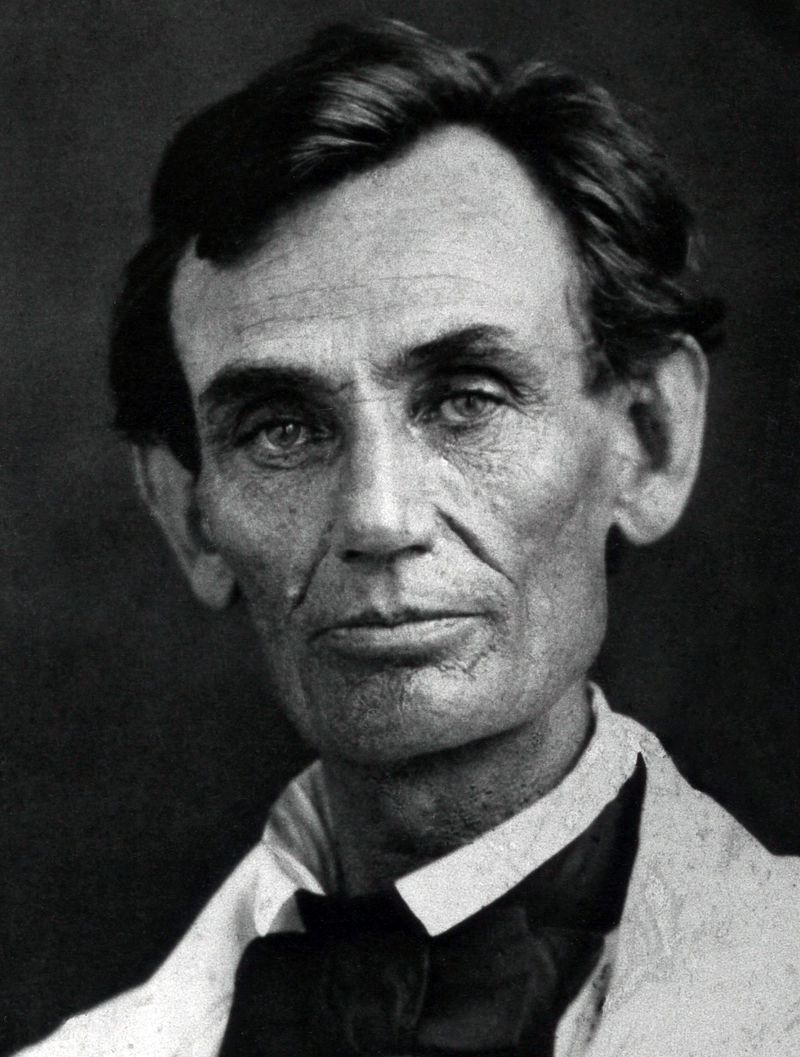

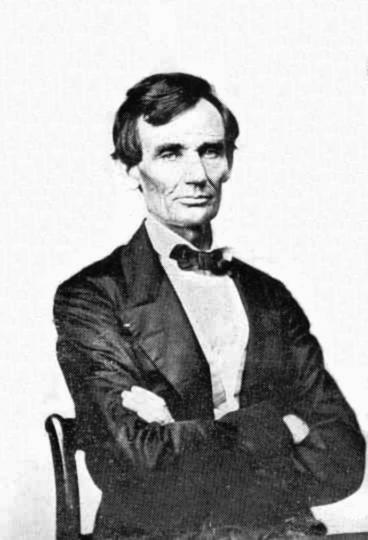

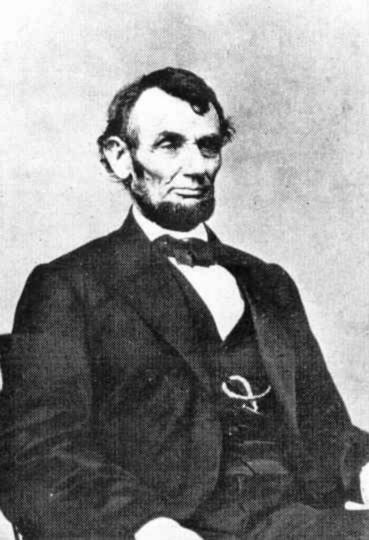

It was an act of God that brought forth out of relative insignificance the one person mentally, morally and spiritually equipped to save the Union. Abraham Lincoln had been born to extreme poverty in Kentucky, lost his mother at an early age, and as a youth followed a hard-handed father into Indiana and then Illinois in search of a better life. He loved to read, no matter what his other activity at the time (reading while plowing?), and had an enormous capacity to remember vast details. Exposed at an early age to extensive tragedy and hardship, he had a susceptibility to depression, which he learned to relieve by studied patience and humor. He was a master storyteller, making him easily popular with common folk. But he himself was no common person. He trained himself in the law and set up practice in the Illinois state capital at Springfield where he developed legal expertise in virtually every branch of the law. He was interested in politics and was elected as a Whig first to the Illinois House of Representatives (1834–1846) and then to the U.S. House of Representatives. But in the latter, as he had promised, he served only a single term (1847–1849), and returned to his law practice supposing that his political career was over. In 1842 he married a Kentucky socialite (from a slave-holding family), Mary Todd, who would be both a source of unyielding resolve and frequent irritation for Lincoln. They had four sons, the second of whom Eddie would die in 1850 at age four. A third son, Willie, was born in the same year as Edward's death, but would himself die in 1862 while the Lincolns were living in the White House. Both parents remained forever distraught over these deaths, deepening Lincoln's sense of melancholy and frequently driving Mary to hysteria. Thus Lincoln developed a huge capacity to carry on in the midst of deep tragedy. As it turned out, his political career was not over (Mary was not about to let that happen!). In 1854 he put himself forward in the contest in the Illinois Assembly for the position of U.S. senator representing his state. He failed (narrowly) to get the appointment, but left a deep impression concerning his dedication to the ending of slavery. He thought of himself as a moderate Whig, focused less on the moral issue of race and slavery than on the obvious contradiction of allowing slavery in a Republic founded on the legal equality of all its people. His most immediate concern was not the total abolition of slavery, but instead the prevention of the spread of slavery into the rest of the nation, a dangerous threat to the Republic as clearly demonstrated by the strife going on in Kansas. With the death of the Whig Party after 1854, Lincoln joined the new Republican Party. At the 1856 Republican National Convention his name was put forward as candidate for Republican vice president, in which he subsequently placed second in the vote. At this point people were beginning to take notice of him as a national political figure.

|

Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln

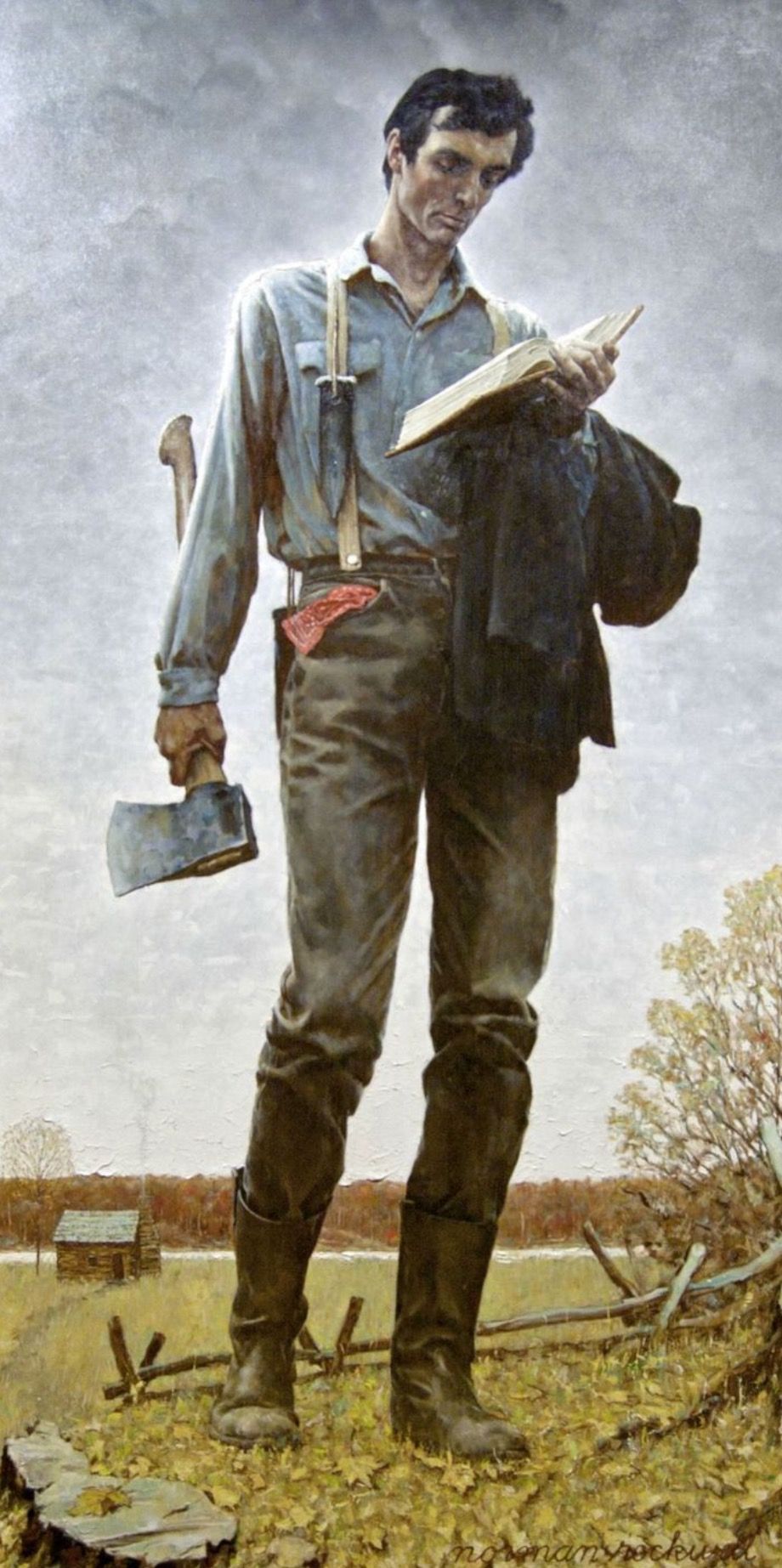

The Railsplitter by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1909)

Young Lincoln – Norman Rockwell

|

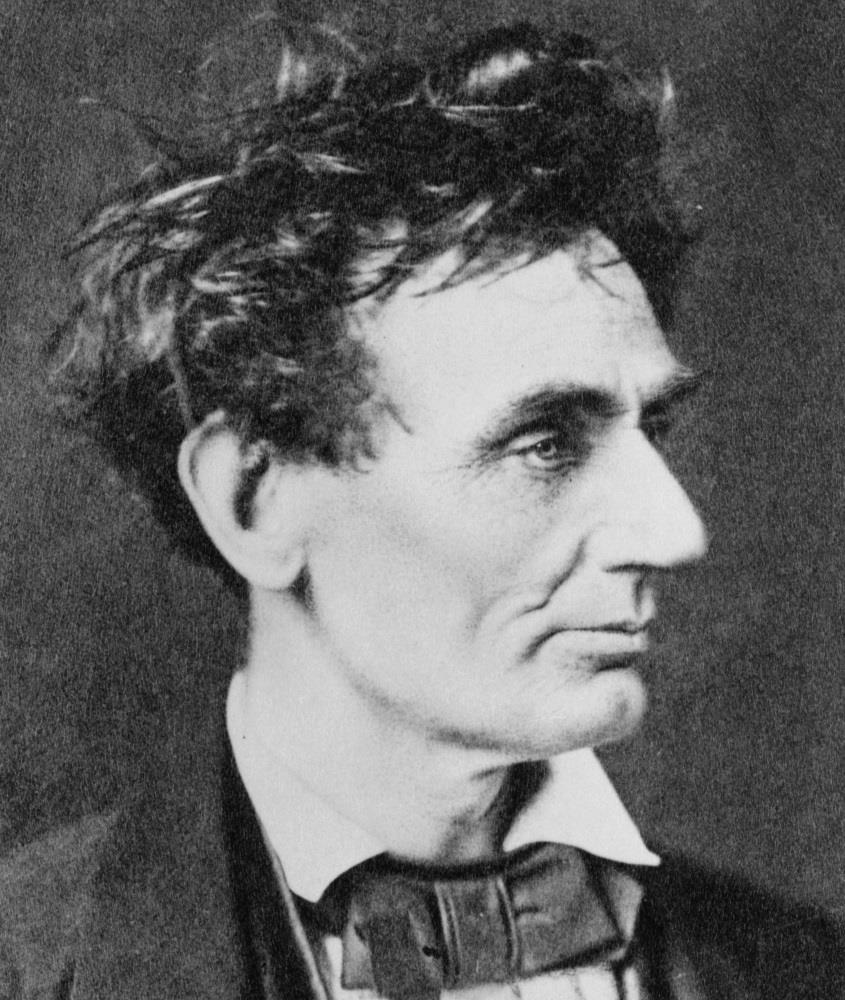

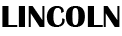

The Lincoln-Douglas debates (August-October 1858)

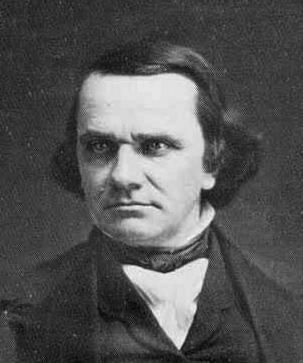

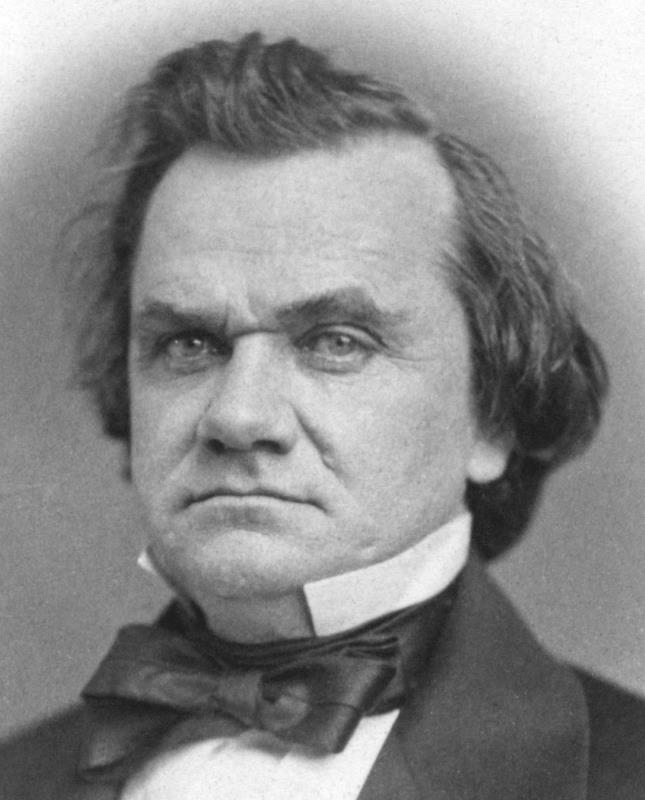

In 1858 the Republicans nominated Lincoln as their candidate for U.S. senator from Illinois, running against the Democratic Party's candidate (and Democratic Party leader in Congress), Stephen Douglas. The two men agreed to meet each other in various parts of the state of Illinois for a series of seven debates. The nation watched closely as the famous Douglas met this new challenger, a seeming country boy with little to commend himself as he took on the "Little Giant" Douglas. But it soon became apparent that this Lincoln was no pushover. Douglas accused Lincoln of being simply another Abolitionist (not yet very popular, even in the North) and Lincoln accused Douglas of surrendering the original moral principles of the Republic in his failure to take any kind of stand against slavery. Thousands gathered, plus the national press, to hear Lincoln and Douglas go at each other. In the end, the Illinois representation was skewed by the way the state was districted and although the Republicans gathered more votes than the Democrats, the Democrats received more seats, and thus the Illinois Assembly re-elected Douglas to represent the state in the U.S. Senate.

|

Lincoln and Douglas

|

The Cooper Union speech (February 1860)

But the Republicans did not forget the brilliant way Lincoln put his arguments together, and in 1860 asked him to address a group of Republican leaders at Cooper Union in New York City. There he recalled the vision of the Republic's Founding Fathers and how they struggled over the issue of slavery. He then answered point by point the arguments of Southerners and of Northern Democrats as they either defended or permitted slavery. And he addressed the threat issued by the South that if a Republican were elected president, they would secede. The Republican leaders were impressed.

|

|

|

Nomination as the Republican presidential candidate (May 1860)

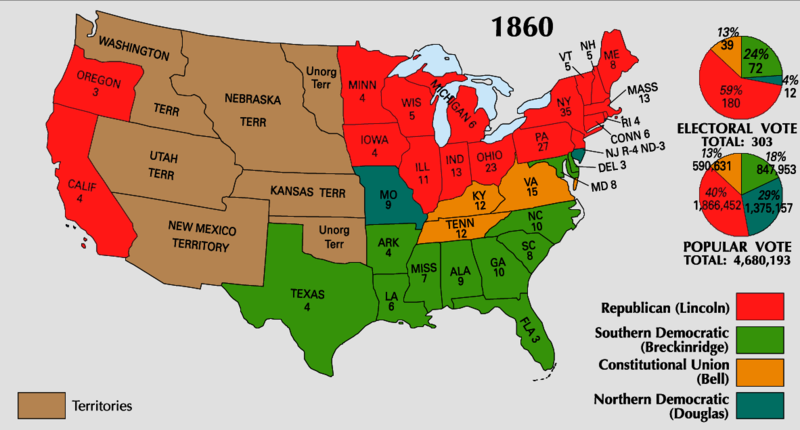

In May the Illinois Republicans decided to get behind Lincoln in a bid for nomination as the Republican Party's presidential candidate. This would be for Lincoln an uphill battle because William Seward and Salmon Chase were widely understood to be the front runners for the nomination. But with a bit of help from his Illinois friends, and much to the surprise of many, Lincoln was nominated for the spot on the Republican National Convention's third ballot. His well-reasoned moderation on the slavery issue and his strong support for the old Whiggish agenda of protective tariffs and internal infrastructure development had won him the day. Meanwhile the Northern Democrats had nominated Douglas as their presidential candidate – although the Southern Democrats withdrew from the Democratic National Convention and nominated their own candidate, John Breckinridge. Lincoln did not campaign directly, as did his opponents. But the Republican Party did the campaigning for him, running on his image as a simple American farm boy who, in the best spirit of the Republic, made his way to success through hard work and study. The tactic worked well. On to the U.S. presidency

In November, with a huge turnout of voters,

Lincoln won a plurality of the popular vote, 1.87 million votes for

Lincoln, 1.38 million for Douglas, 850 thousand for Breckinridge and

589 thousand for a fourth candidate, John Bell – but an absolute

majority of the electoral vote, 180 votes to his opponents combined

total of 123 votes. Lincoln was thus elected to be the nation's

sixteenth president.

|

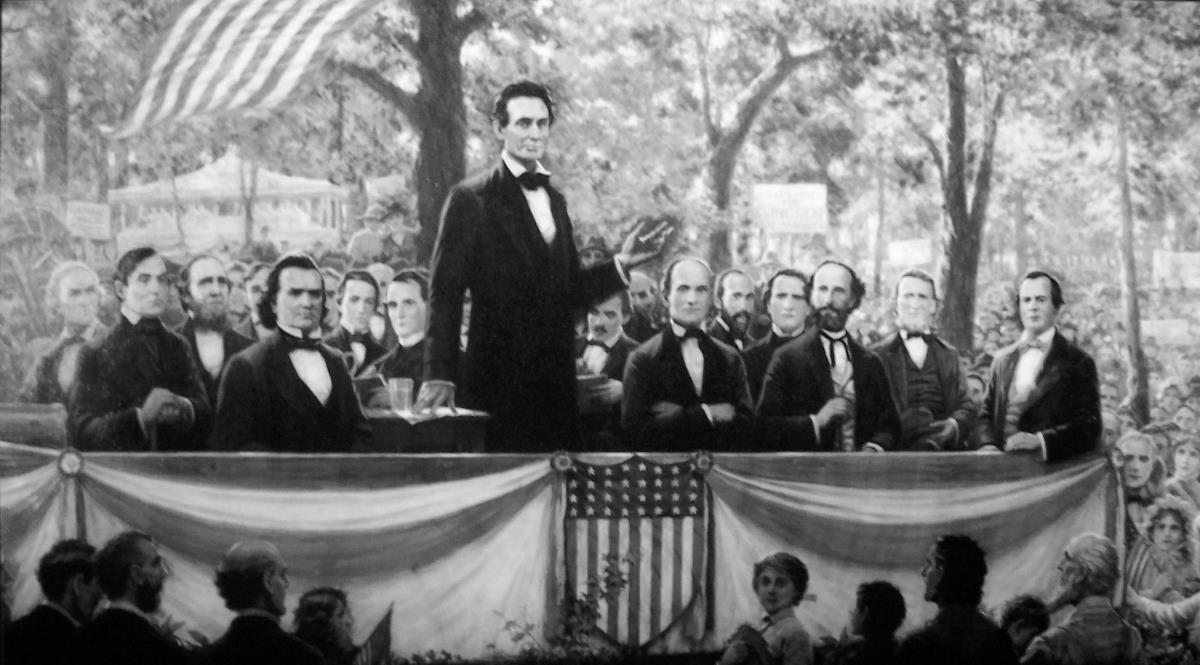

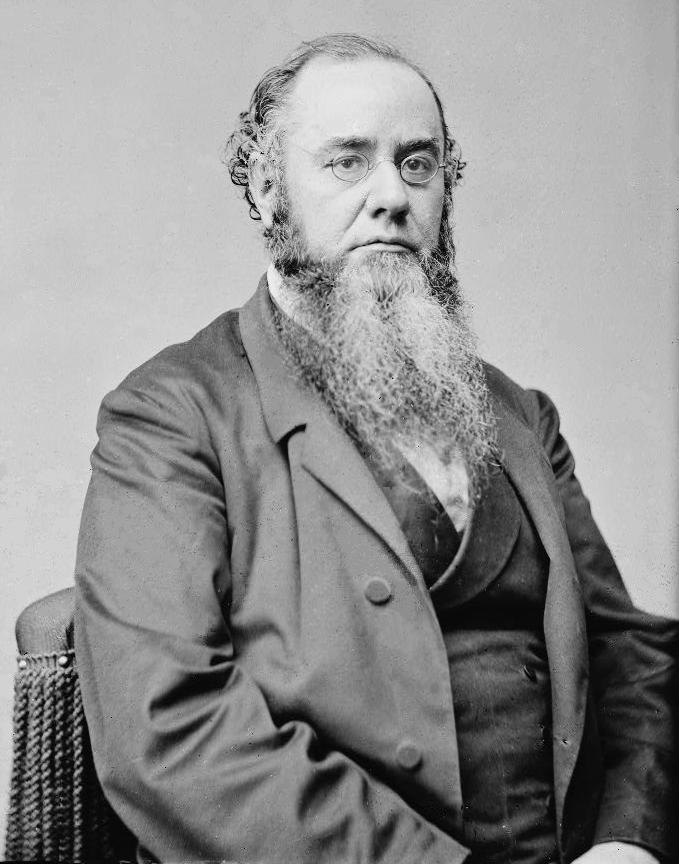

Sen. Stephen A.

Douglas |

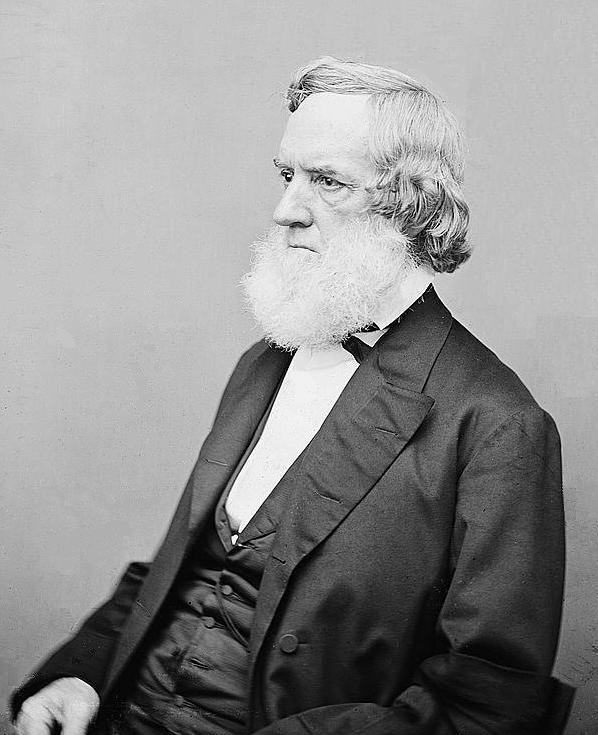

John C. Breckinridge |

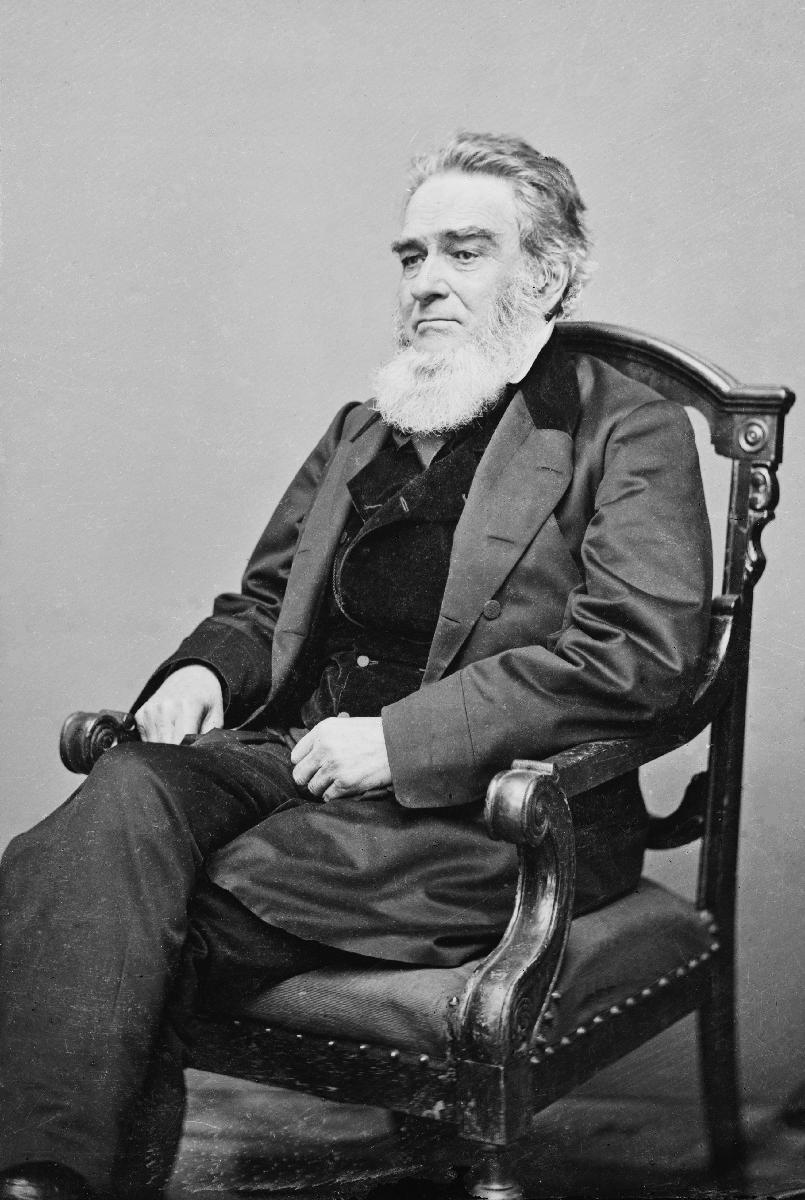

John Bell |

Library of Congress (left)

/ National Archives (right)

|

|

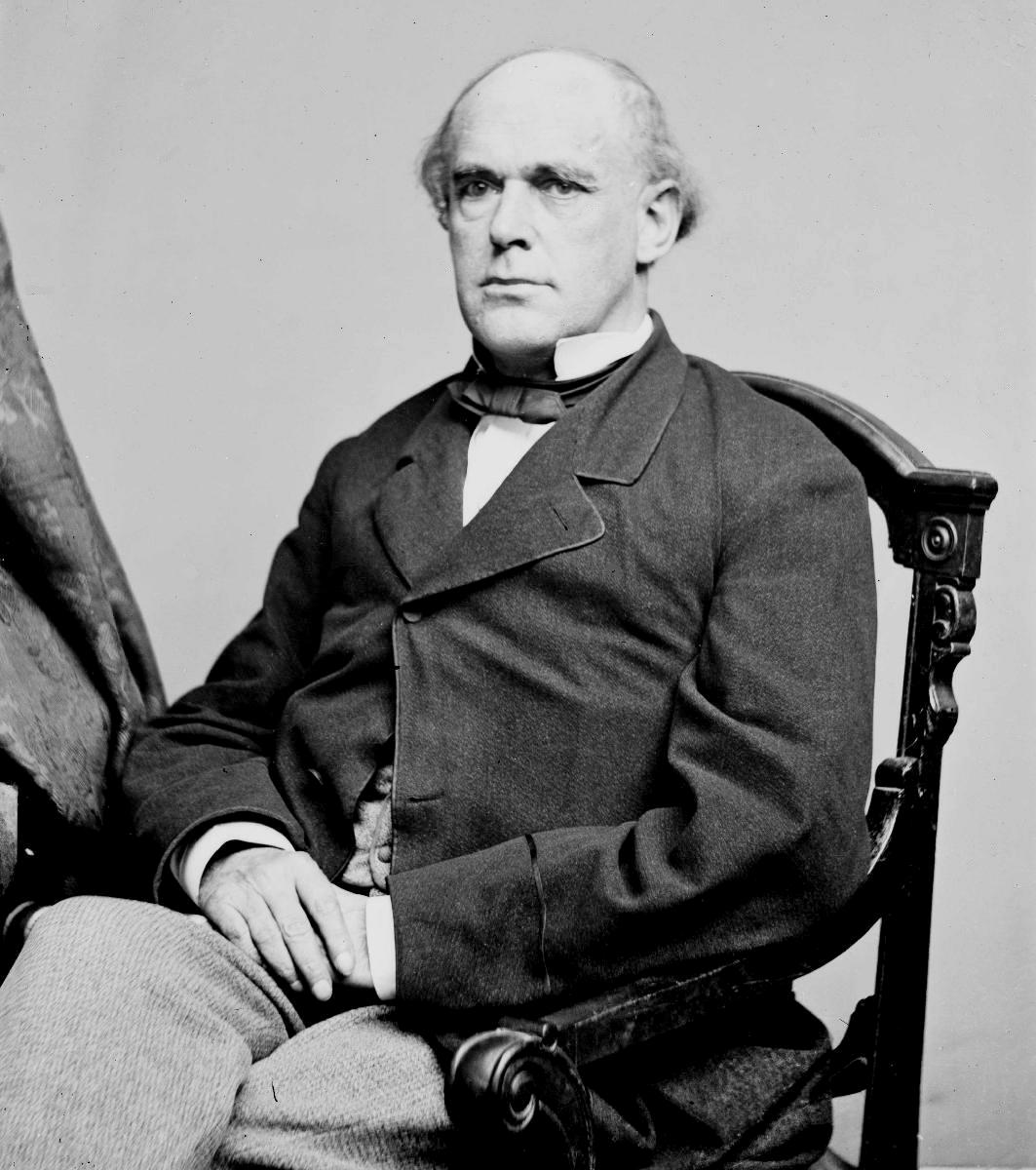

Lincoln then took the somewhat unprecedented step of appointing to his cabinet a number of his major political rivals, William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Edward Bates, among others. At first these political dignitaries tended to be contemptuous of him2 and his country boy ways. But gradually they all (except Chase) came to see Lincoln's true political genius and came to full support of him as their president. Chase was retained in Lincoln's cabinet despite his behind-the-scenes maneuvering to have himself replace Lincoln as Republican candidate in the elections coming up in 1864, because Lincoln respected Chase's financial skills. Lincoln eventually (1864) appointed him as chief justice of the Supreme Court, removing a constant irritant on his cabinet, but giving the country a chief justice guaranteed to stand in support of the rise to citizenship of America's freed slaves. As for Seward, he soon became a totally-devoted supporter of Lincoln's, very important to the president during the dark days ahead. 1Team of Rivals is the title of a Simon & Schuster 2005 Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Doris Kearns Goodwin, in which she demonstrated the political genius of Lincoln in appointing to his cabinet a number of his recent political opponents. 2Seward

even at first proposed to Lincoln to have him turn all real powers of

the presidency over to himself, and then proposed a bizarre foreign

policy to isolate the South, all of which Lincoln politely ignored as

he moved steadily ahead with his own policies for dealing with the

rising crisis. |

Secretary of State of the

United States (1861-1869)

Governor of New York

(1839-1842)

United States Senator from

New York (1849-1861)

Library of Congress

United States Secretary

of the Treasury (1861-1864)

United States Senator from

Ohio (1849-1855)

Governor of Ohio

(1856-1860)

6th Chief Justice of the

United States (1864-1873)

United States Secretary

of War (1862-1868)

United States Attorney General

(1860-1861)

Library of Congress

United States Secretary

of the Navy (1861-1869)

Library of Congress

US Attorney General

(1861-1864)

Library of Congress

United States Postmaster

General (1861-1864)

Library of Congress

|

|

Lincoln had only very limited war experience and no formal military training, in contrast to his chief adversary, Jefferson Davis, Confederate president and graduate of West Point and a commanding officer (colonel) in the Mexican-American War.3 But Lincoln had a keen mind for strategy, a deep insight into the character of others, and an awareness that he needed wise war counsel – which he got from the elderly Winfield Scott4 and eventually from his war cabinet. Being a lawyer, he tended to think through objectives better than the military men under him, who tended to think mostly in terms of battle strategies designed to win battles. Lincoln however thought in terms of war strategies (economics, diplomacy, ideology, morale, as well as military engagements) designed to win a war. Lincoln the Christian

There seems to have been nothing particularly remarkable about Lincoln's religious or spiritual nature going into the White House in 1861. As president he would attend frequently the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington. But he was definitely not what you would call a churchy individual. However, the four years of the presidency would have a tremendous impact on how he made his way forward through life's many challenges. He was a sensitive man, which made him all the more vulnerable to the criticism and personal attacks that others would aim at him. He was called on to lead a war, which meant the deaths of countless young men, both Southern as well as Northern Americans, all of which burdened his heart deeply. There would always be political voices claiming that he was going too slow – or too fast – in his conduct of the war. There would be subordinates who would disappoint him deeply with their failures to live up to their responsibilities, others who because of their own political ambitions would undercut him in order to bring him down. Even within his cabinet – even within his own home (his wife could be brutal in her sarcasm and withering criticism) – he often had to face dispiriting opposition. What held Lincoln together was not man, not man's opinions, not man's advice. What kept Lincoln going during these extremely stressful years was his growing sense of the hand of God in placing him in the presidency, and the grace of God in providing the only counsel he could depend on. He had an ever-deepening sense that all of this tragedy was a way that God was cleansing the nation of its sins, in order to restore it to its longstanding status as a model society, a true Christian nation and thus a greatly needed democratic light to the world. As he put the matter at Gettysburg in November of 1863 in honoring those who had died for this just cause: Americans must "resolve ... that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." This attitude was brought into even higher relief in his second inaugural address in March of 1865 (just weeks before his assassination) when the entire second half of the speech focused on how the nation must answer to the righteous judgments of God, and how it is imperative at this point "with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, to finish the work, to bind up the nation's wounds, to achieve a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations." Here was truly a man of God. 3Davis presumed himself to be militarily wise and thus failed to seek good counsel. In fact he involved himself too deeply in the running of the war at the field level, making things even more difficult for his generals. 4Lincoln's Anaconda strategy, to surround and strangle the South into submission, was the brain-child of Scott.

|

Go on to the next section: The Nation Finally Divides

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges