The

war had begun. On April 15th, Lincoln called on the states for 75,000

volunteers to build up the Union army in preparation for the conflict

ahead. The Tennessee governor flatly refused, indicating his readiness

to join the Confederacy – which Tennessee did on May 7th. Arkansas

announced its decision to secede on May 6th. Virginia voted in

convention on April 17th to secede, confirmed in a popular referendum

on May 23rd. And on May 20th North Carolina also joined the group of

secessionists. The Confederacy now had eleven members. Kentucky also

refused to send troops to Lincoln, though Kentucky was not going to be

joining the Confederacy but instead was going to remain neutral.

However, in a number of important ways, this proved to be strategically

more beneficial to the Union than to the Confederacy.

The

war had begun. On April 15th, Lincoln called on the states for 75,000

volunteers to build up the Union army in preparation for the conflict

ahead. The Tennessee governor flatly refused, indicating his readiness

to join the Confederacy – which Tennessee did on May 7th. Arkansas

announced its decision to secede on May 6th. Virginia voted in

convention on April 17th to secede, confirmed in a popular referendum

on May 23rd. And on May 20th North Carolina also joined the group of

secessionists. The Confederacy now had eleven members. Kentucky also

refused to send troops to Lincoln, though Kentucky was not going to be

joining the Confederacy but instead was going to remain neutral.

However, in a number of important ways, this proved to be strategically

more beneficial to the Union than to the Confederacy.

Slave-holding Maryland and Delaware did

not secede, in part because they were divided in opinion on the matter

and in part because they were under the federal gun not to secede.

Lincoln was intent on not having the Union capital at Washington lose

its link with the North by being surrounded by a rebellious South.

Lincoln moved swiftly to stop any idea of Maryland seceding, declaring

martial law,1 sending

troops in to secure strategic positions in the state, arresting large

numbers of Maryland officials, and suspending the writ of habeas corpus,2 despite the protest of Supreme Court Chief Justice Taney (himself a Marylander).

Missouri, like other border states, was

divided in its loyalties. But in the end a Missouri convention called

to decide the matter chose almost unanimously to remain loyal to the

Union. Missouri Governor Jackson took the opposite position and called

out the state militia to enforce his pro-slavery stance. But he was

attacked by federal forces, chased with his supporters out of the

Missouri state capital, and pushed down into the southern part of the

state. The members of the convention choosing for the Union then took

over the running of the state. But Missouri would itself remain a

center of the North-South struggle for the rest of the War.

In Virginia citizens of the western

counties were opposed to Virginia's decision to secede from the Union

and instead chose to secede from Virginia and the Confederacy, forming

the new (pro-Union) state of West Virginia.

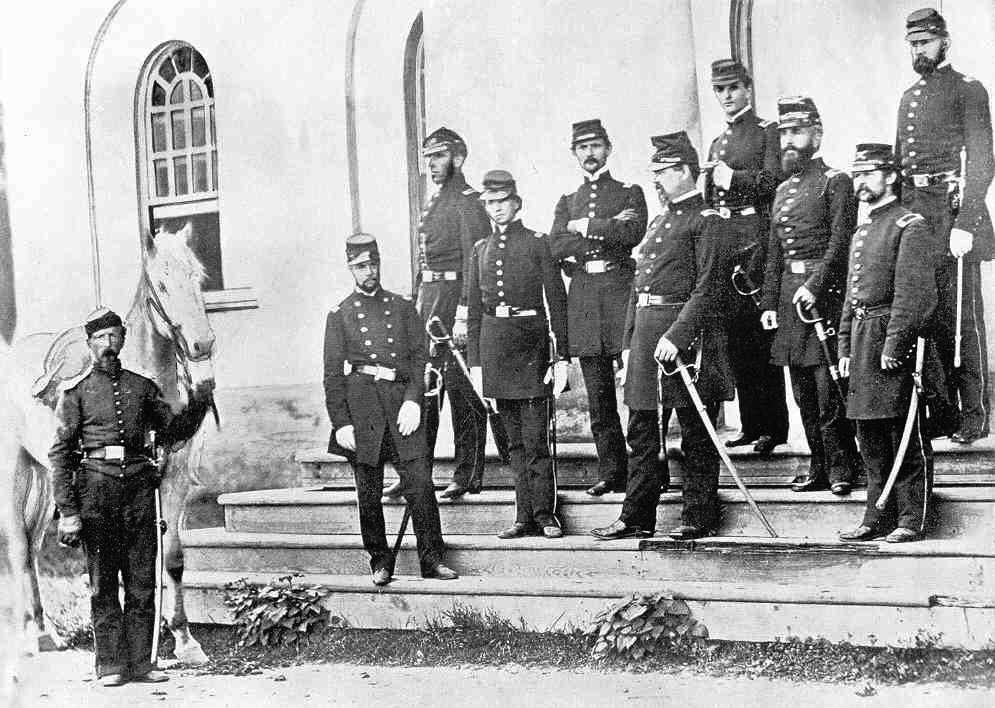

In the meantime, thousands of soldiers

rushed to join the state militias both North and South, excited to get

involved in this opportunity for personal glory. But as with all such

early rushes to war, the excitement would quickly subside once the

cruel reality of war began to register.

In material terms, this was bound to be

an unequal fight. The North had three times the number of men eligible

for military service as the South – Southern Blacks of course excluded.

And while the huge number of Southern Blacks provided work units

supporting the Confederate army, they needed considerable supervising

to ensure their cooperation, taking a good number of Whites out of

military service. Also, the emphasis of "Cotton as King" now would

haunt the South because it had caused the region to ignore emerging

industrial development. Thus the South fell way behind the North in the

production of everything from ammunition and uniforms to canons and

railroad engines.

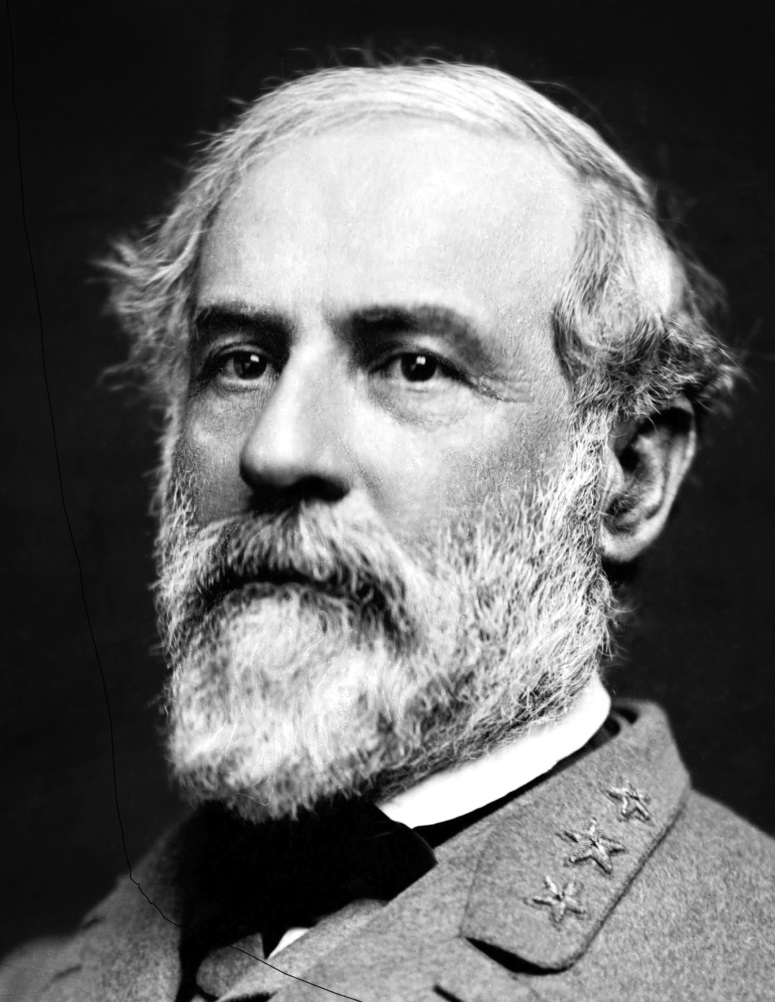

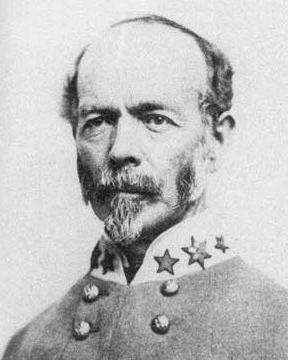

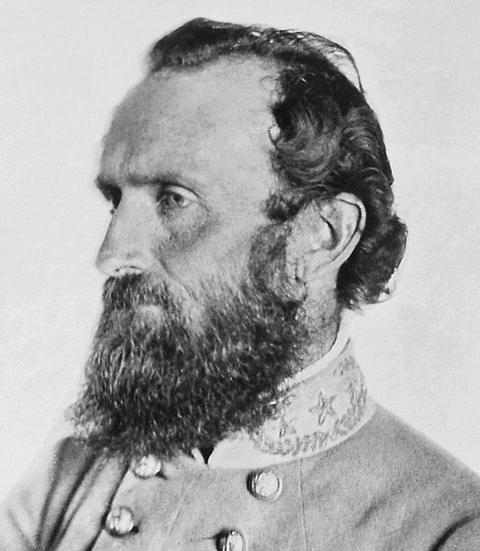

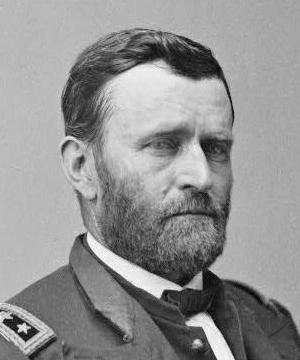

On the other hand, Southerners had made

up a disproportionately large percentage of America's experienced

(Mexican-American War) army officer corps prior to the war. Most of

these would quit the U.S. army to take assignments in the Confederate

army. The superior quality of the Confederate officers would show in

the way the South tended to embarrass the Northern armies whenever they

met in battle, at least during the first years of the war. The fact

that even with all this material superiority it took the North four

years to bring the South to defeat stood in part as testimony to the

superior military leadership found within the Confederate forces.

The purpose of war is to get an adversary to

stop doing – or even being – what it is that a society pursuing war

finds detestable in the thoughts and behavior of that adversary. To get

the adversary to yield in this matter requires an enormous amount of

pressure put on the adversary. That pressure can take all kinds of

forms, military, economic, psychological. But whatever it takes, the

object is always the same: to get the adversary to stop whatever it is

that they have been doing – to just quit.

For the South, the strategy was simply to

get the North to let the slave-holding states withdraw from the Union

so that the South could continue to pursue its cultural dream of an

elegant semi-feudal social order consisting of a genteel plantation

society engaged in endless rounds of fancy social gatherings, the whole

social program supported by the labors of multitudes of Black slaves.

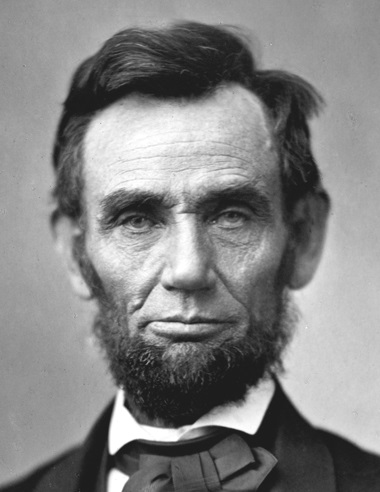

For the North the goal of war – and thus

the strategy involved – was much less uniform in inspiration, Northern

groups often working at odds with each other. For some, the goal was to

eradicate the institution of slavery from the entire North American

continent. For others it was to simply force the South to continue to

honor its commitment to the unity of the United States of America, even

if that meant backing off on the slavery issue. Yet for others it was a

similar hope of enforcing that unity, and ending slavery in America as

well. This lack of unity of purpose would make things very difficult

for anyone given presidential responsibility, as previous holders of

the office of U.S. president had already discovered. Thus the newly

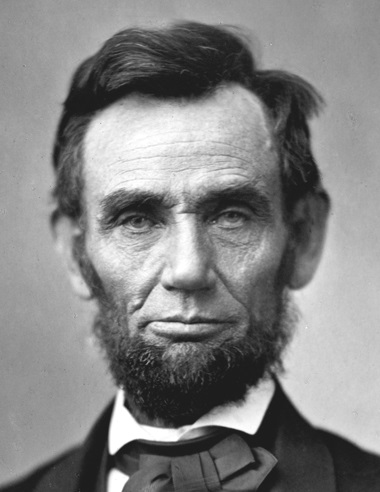

installed president Lincoln knew that he had been called to undertake a

task of unimaginable difficulty.

He had therefore a dual set of

responsibilities, as he understood the challenge personally. He was

determined fully, almost regardless of the costs involved, to maintain

the unity of the federal Union. That meant full war against any states

undertaking rebellion against the Union. But he also had to provide the

North with a rallying point that would unite all these conflicting

Northern viewpoints. Failure in holding such unity of purpose in the

North would be to deliver the South the victory it sought.

As far as the slavery issue went, Lincoln

was very cautious about waving the flag of Abolitionism, because not

only would it complicate the task of keeping the North united, it would

merely steel the resolve of the South to continue its struggle,

regardless of the costs involved. After all, the purpose of war is to

weaken the resolve of the adversary, not strengthen it.

Nonetheless, Lincoln well understood that

the slavery issue was at the heart of the crisis that had split the

Union. One way or another the slavery issue could no longer be allowed

to infect America's national health. Slavery was going to have to

disappear. But just how that would happen, Lincoln seemed to have no

particular strategy in mind. He seemed resolved to leave that question

up to the fortunes of war – and to God, on whom he relied ever-heavier

as the war between the Northern and Southern states dragged on.

What

Lincoln was clear on was his military-economic strategy by which he

intended to force the Southern states to give up their rebellion and

once again take their place as full members of the Union. Basically,

his strategy (aided tremendously in its conception by his military

advisor, the old warrior General Winfield Scott)

was to surround and isolate the South militarily – north, south, east

and west – and thus shut down their cotton-export economy on which the

Southern dream depended so completely.

What

Lincoln was clear on was his military-economic strategy by which he

intended to force the Southern states to give up their rebellion and

once again take their place as full members of the Union. Basically,

his strategy (aided tremendously in its conception by his military

advisor, the old warrior General Winfield Scott)

was to surround and isolate the South militarily – north, south, east

and west – and thus shut down their cotton-export economy on which the

Southern dream depended so completely.

This was going to hurt the textile mills

of the North, which depended heavily on the ability to acquire Southern

cotton. But that would be one of the sad prices of war. But Lincoln was

aware that this war was going to be costly – very costly – on a number

of fronts. But the Union had to be preserved at all costs, or there

would be no very good future for any of the states, North or South.

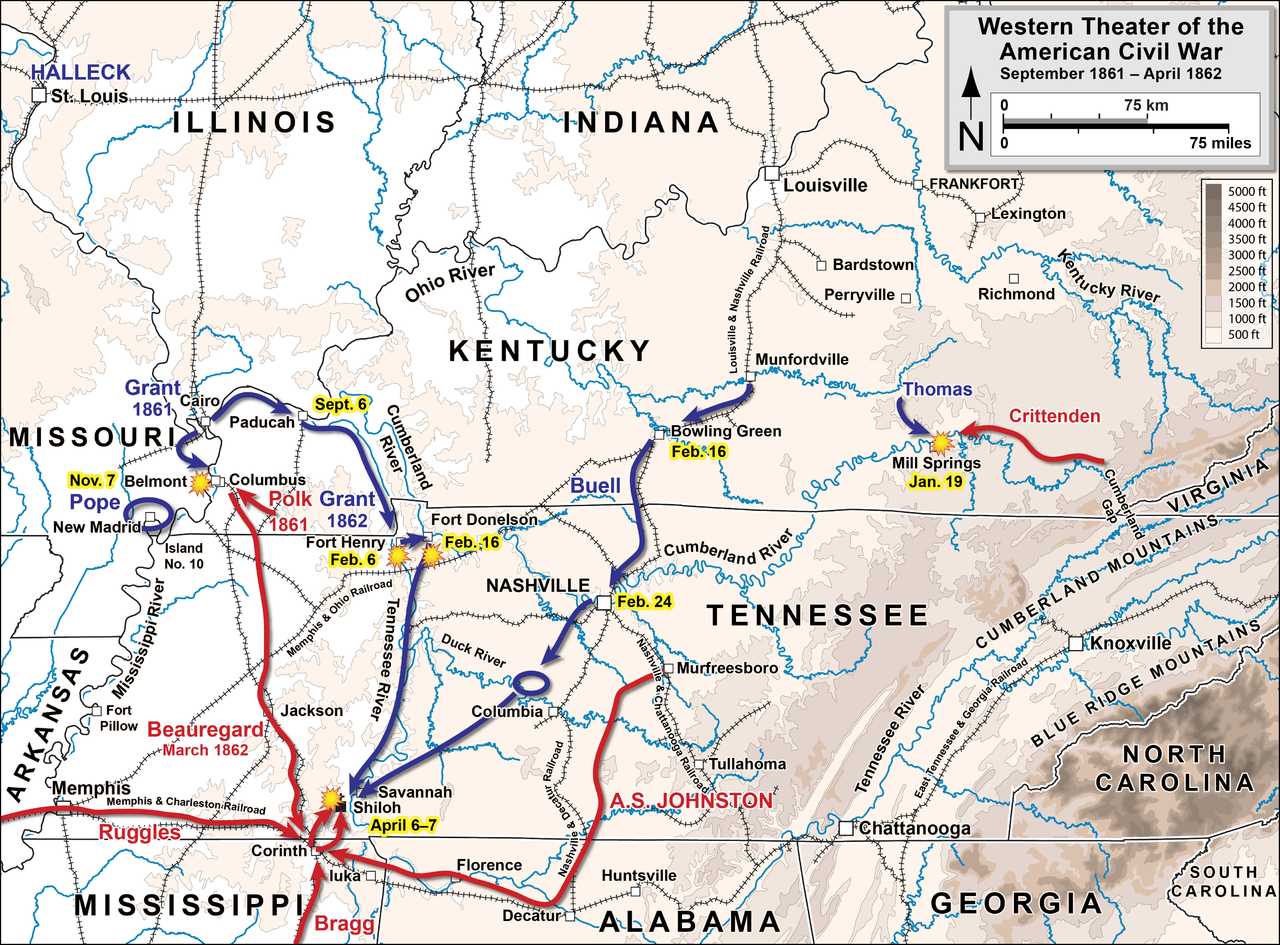

And thus it was that in pursuit of this

strategy of strangulation (the Anaconda Strategy as it was termed), the

Civil War was conducted simultaneously on a number of key fronts. The

most important front was the one that developed in Northern Virginia,

the spiritual heartland of the South. Another was the maritime front

that extended from the Chesapeake in Virginia, south along the Carolina

and Georgia coasts, around Florida, and into the Gulf of Mexico just

south of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Another was along

the Mississippi River, which separated the Confederate states of the

Deep South (Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana) from the

Confederate states of the Southwest (Texas and Arkansas). A fourth

front was at the very center of the North-South border, basically

within the states of Kentucky and Tennessee (and the northwestern

section of Georgia). Four different fronts, and four different armies

(or navies), all trying to tighten the noose around the rebellious

South.

Not only would the political task of

maintaining unity at home against the partisan political interests of

ambitious Northern politicians be a constant challenge for Lincoln, but

perhaps even weightier would be the task of finding military leaders

able to understand Lincoln's strategy of war. Again, soldiers are

notorious for wanting to win battles (and thus battlefield fame)

without seeming to understand how that connects with the larger

challenge of winning the war that has called forth these battles.

General Washington understood this. So did General Winfield Scott. But

Washington was long dead, and the very elderly Scott was not far behind

him. Lincoln needed a wise, not just an ambitious, general to supervise

the military portion of his general strategy. Lincoln would soon

discover how difficult it would be to find just such a general.

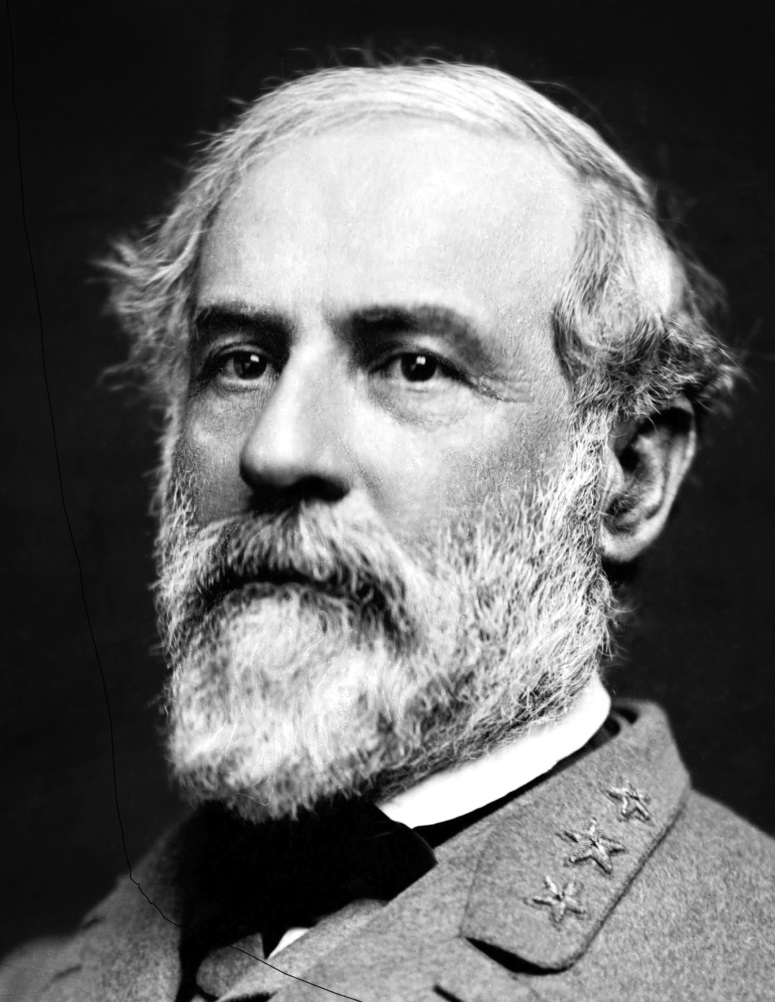

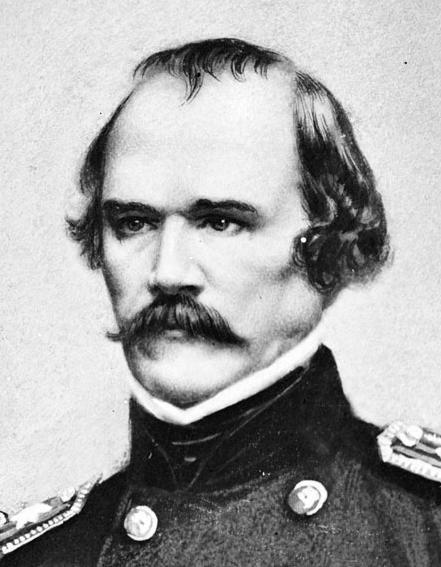

Robert E. Lee

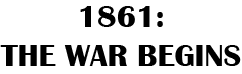

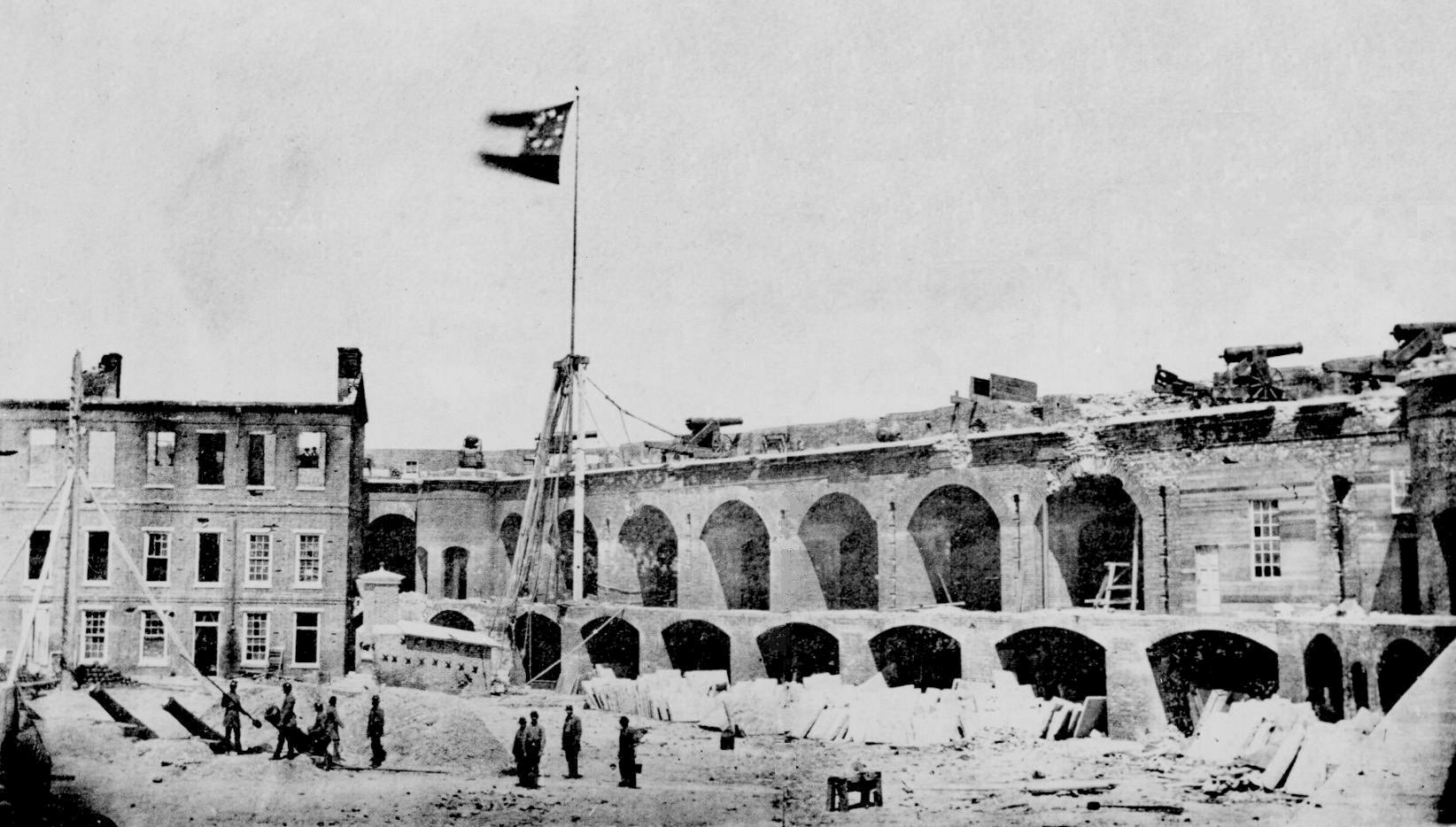

The

attack on Fort Sumter (April 12-15)

The

attack on Fort Sumter (April 12-15) The strategies of war

The strategies of war

The

first battle of Manassas or Bull Run (July 21)

The

first battle of Manassas or Bull Run (July 21)

The battle further west

The battle further west The

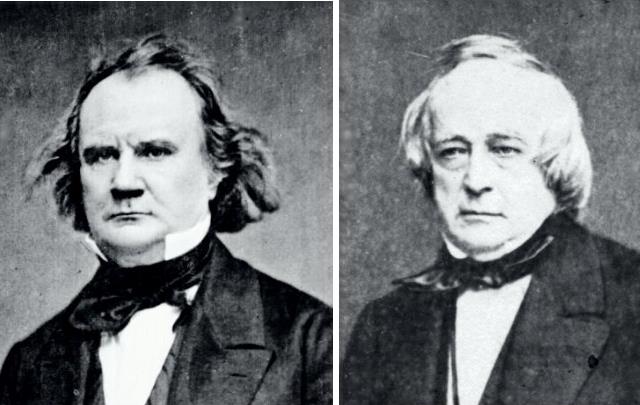

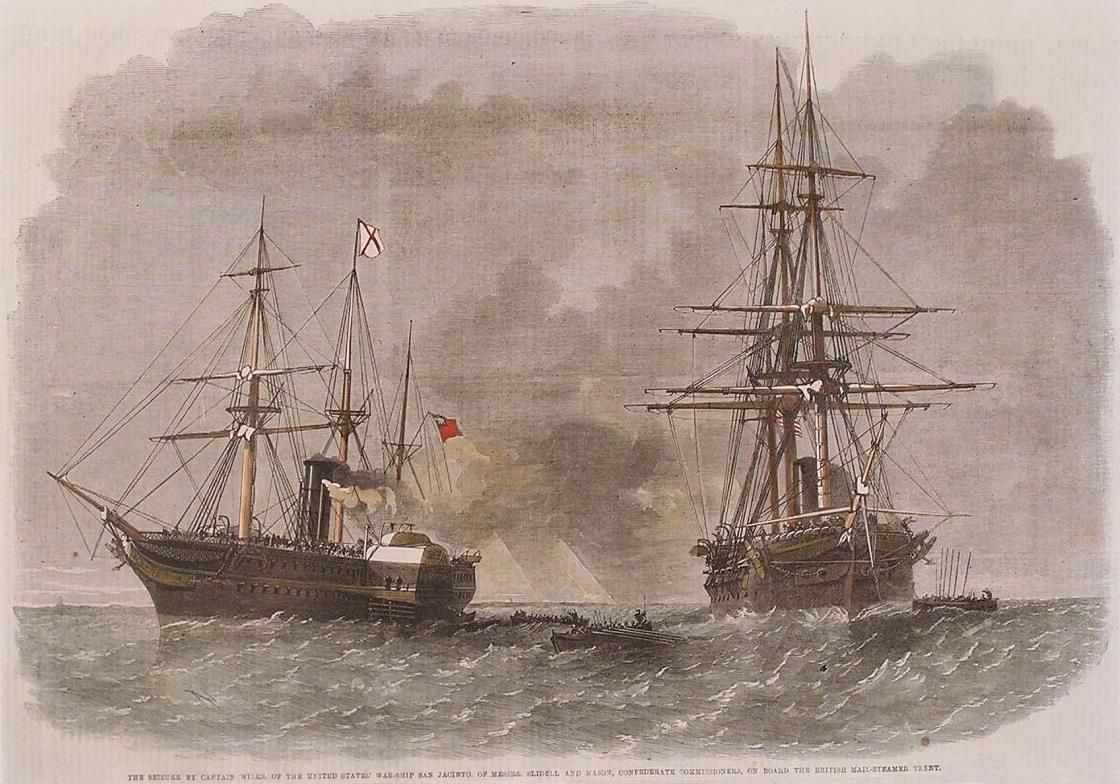

Mason-Slidell Affair (November 8)

The

Mason-Slidell Affair (November 8)

The

war had begun. On April 15th, Lincoln called on the states for 75,000

volunteers to build up the Union army in preparation for the conflict

ahead. The Tennessee governor flatly refused, indicating his readiness

to join the Confederacy – which Tennessee did on May 7th. Arkansas

announced its decision to secede on May 6th. Virginia voted in

convention on April 17th to secede, confirmed in a popular referendum

on May 23rd. And on May 20th North Carolina also joined the group of

secessionists. The Confederacy now had eleven members. Kentucky also

refused to send troops to Lincoln, though Kentucky was not going to be

joining the Confederacy but instead was going to remain neutral.

However, in a number of important ways, this proved to be strategically

more beneficial to the Union than to the Confederacy.

The

war had begun. On April 15th, Lincoln called on the states for 75,000

volunteers to build up the Union army in preparation for the conflict

ahead. The Tennessee governor flatly refused, indicating his readiness

to join the Confederacy – which Tennessee did on May 7th. Arkansas

announced its decision to secede on May 6th. Virginia voted in

convention on April 17th to secede, confirmed in a popular referendum

on May 23rd. And on May 20th North Carolina also joined the group of

secessionists. The Confederacy now had eleven members. Kentucky also

refused to send troops to Lincoln, though Kentucky was not going to be

joining the Confederacy but instead was going to remain neutral.

However, in a number of important ways, this proved to be strategically

more beneficial to the Union than to the Confederacy. What

Lincoln was clear on was his military-economic strategy by which he

intended to force the Southern states to give up their rebellion and

once again take their place as full members of the Union. Basically,

his strategy (aided tremendously in its conception by his military

advisor, the old warrior

What

Lincoln was clear on was his military-economic strategy by which he

intended to force the Southern states to give up their rebellion and

once again take their place as full members of the Union. Basically,

his strategy (aided tremendously in its conception by his military

advisor, the old warrior

But Virginia was not going to let that go

unchallenged, and the Army of Virginia gathered forces to head north

towards Washington. Lincoln sent out the Army of the Potomac, with its

36,000 men under an inexperienced

But Virginia was not going to let that go

unchallenged, and the Army of Virginia gathered forces to head north

towards Washington. Lincoln sent out the Army of the Potomac, with its

36,000 men under an inexperienced

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges