With the Union naval blockade in place and the

South now unable to get to or from the high seas, the South's vital

export business was crippled.

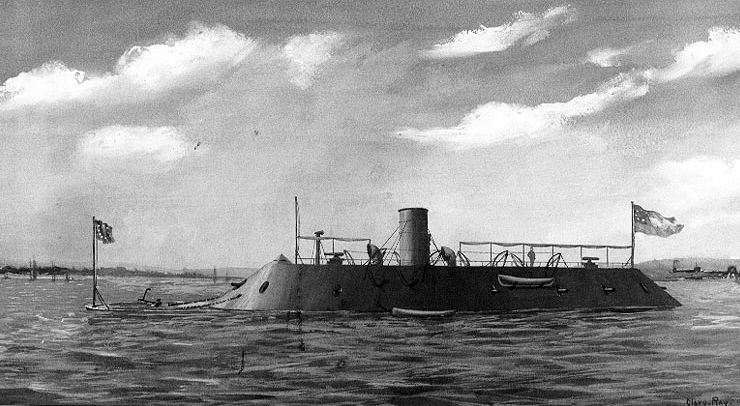

But

Confederate naval designers came up with an ingenious plan. They

would restore the sunken Union steam-driven frigate, the Merrimac,

and cover her topsides with steel plating which would make her

invulnerable to Union cannons. This would turn her into a terror

against the blockading Union fleet.

On March 2nd, renamed the Virginia,

this ten-cannon monster (operating under steam power and thus needing

no masts, and showing only slanting ironclad sides above water) steamed

into the Union fleet blockading the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay,

creating havoc. She rammed and sank the Cumberland, sank the Congress, and ran the Minnesota aground before night set in and she returned to port.

On the following morning she headed out toward the Union fleet with the intention of finishing off the Minnesota

and then turning on the three other Union ships still blockading the

harbor. But she was met by an equally strange ironclad sailing vessel,

the Monitor,

that the North had hastily put together when it first got wind of the

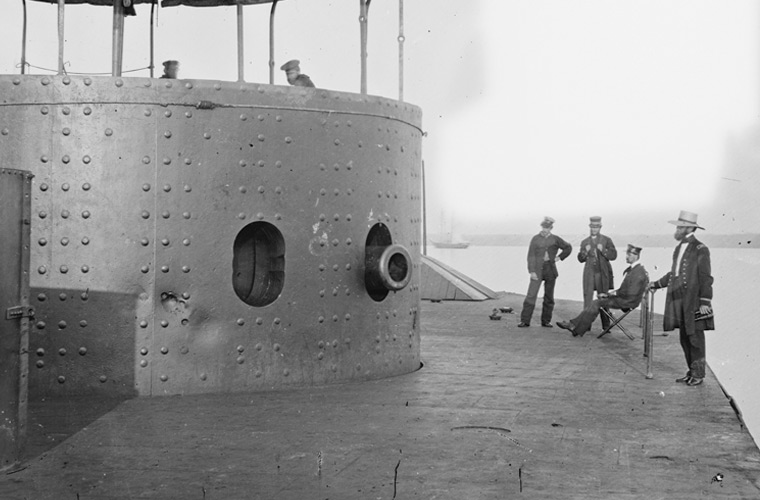

South's intention of building an ironclad ship. The Monitor

was just a round turret with two canons inside sitting atop a flat

barge whose deck barely rose above the water. These two monster

machines met and for four hours blasted away at each other. The match

finally ended when the Virginia (formerly Merrimac) withdrew. Overall however, there was no victor and no vanquished in this battle.

The two ships never met again. Then that May, the Union army captured Norfolk, the operational base of the Virginia.

Thus with nowhere to operate from, and with the South not wishing to

surrender the Virginia to the North, her crew blew her up.

The

battle of the ironclads at Hampton Roads (March 3)

The

battle of the ironclads at Hampton Roads (March 3)

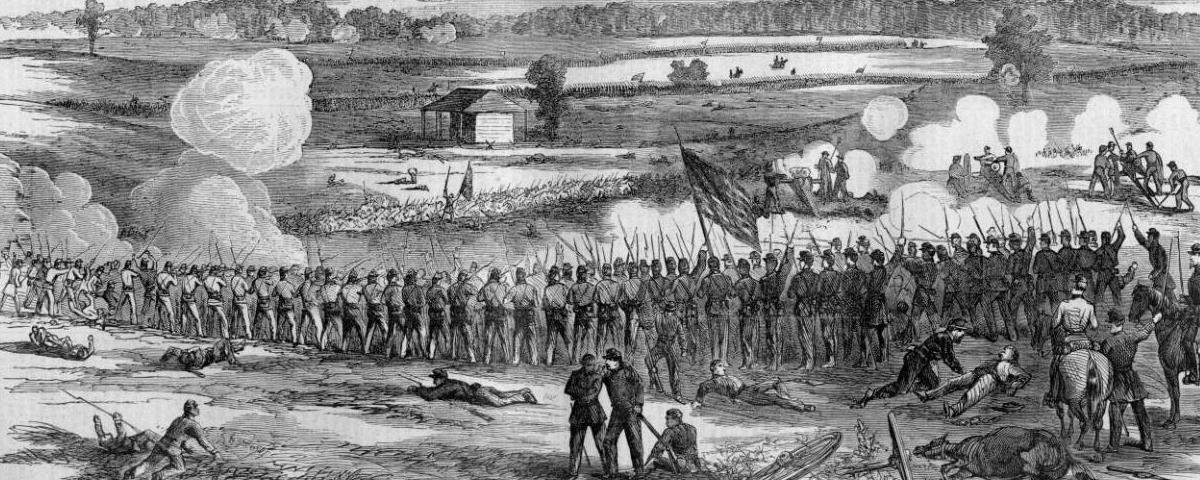

The battle in the West

The battle in the West

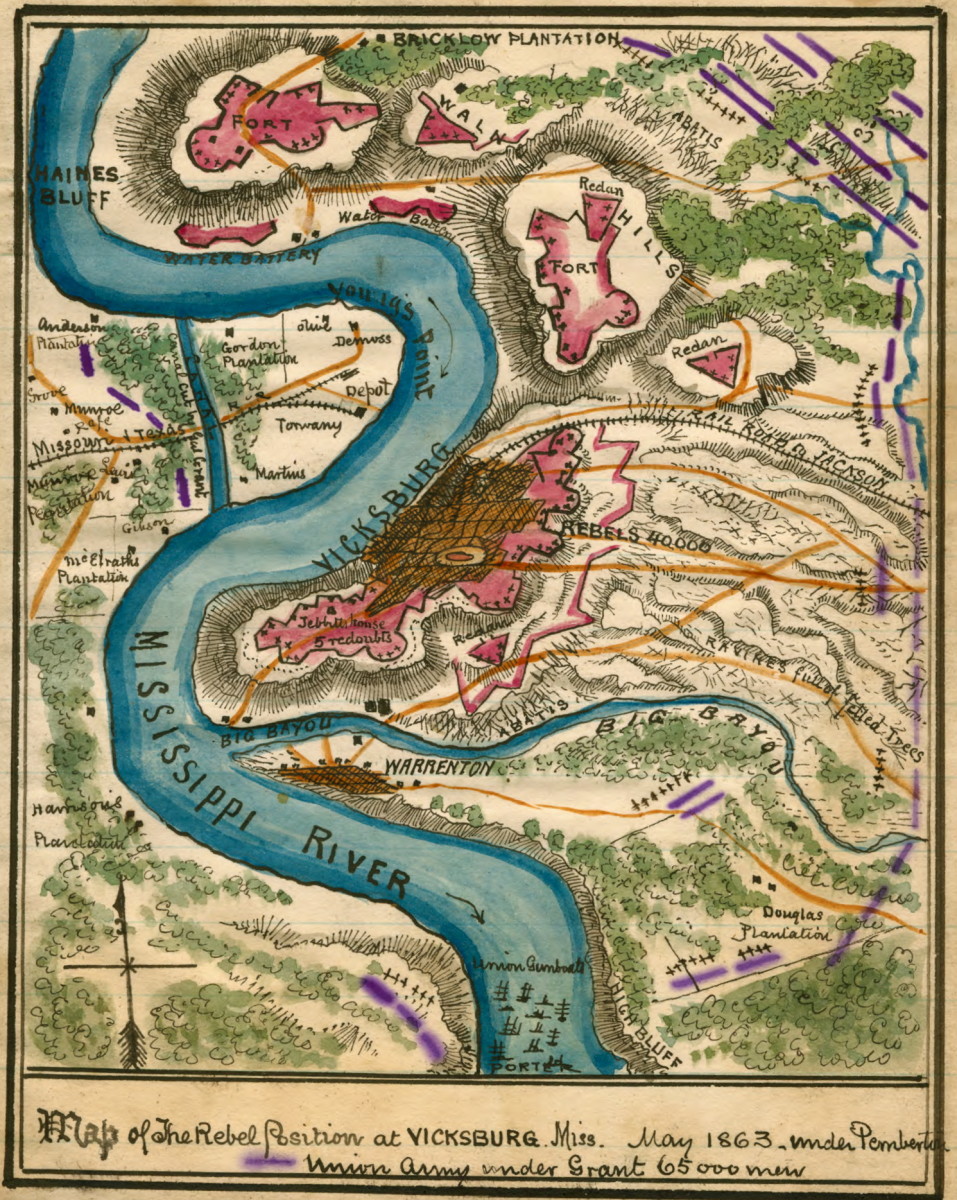

The battle for control of the Mississippi River

The battle for control of the Mississippi River

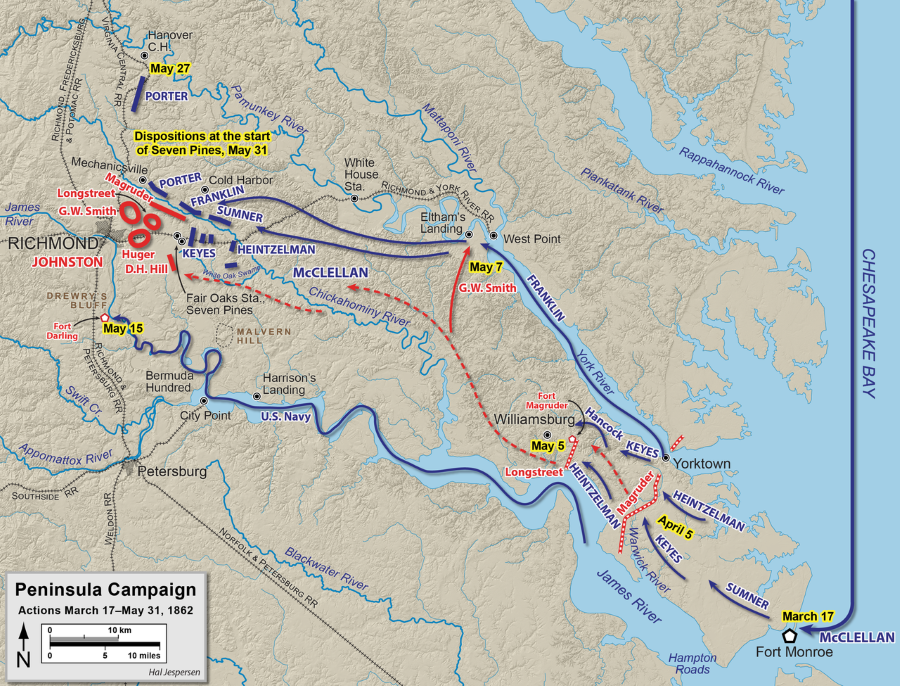

McClellan's Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles

McClellan's Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles

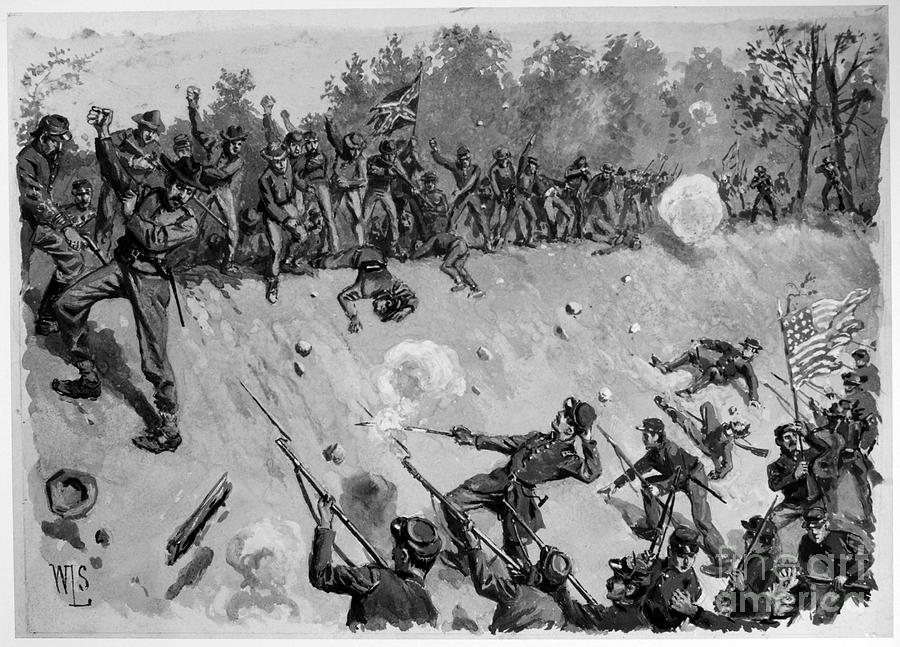

The Second Battle of Manassas (or Bull Run) – August

29-30

The Second Battle of Manassas (or Bull Run) – August

29-30

Antietam (or Sharpsburg) – September 17

Antietam (or Sharpsburg) – September 17

The Emancipation Proclamation (September

22)

The Emancipation Proclamation (September

22) Further action in the West (October)

Further action in the West (October)

Fredericksburg

(December 11 – 15)

Fredericksburg

(December 11 – 15)

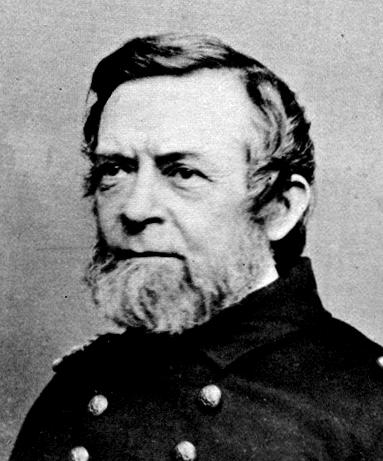

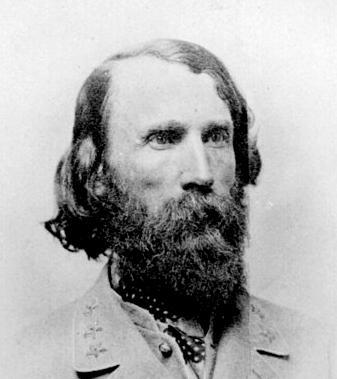

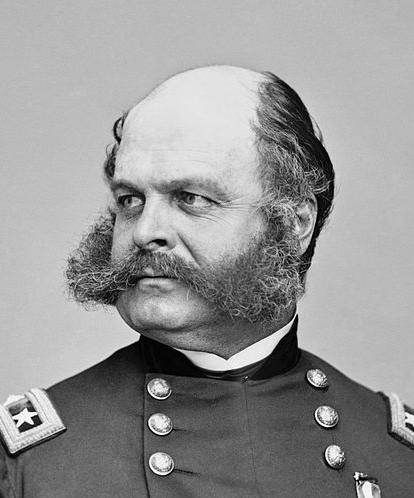

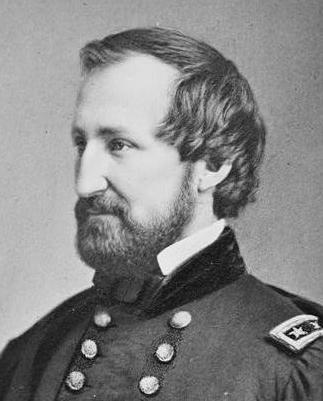

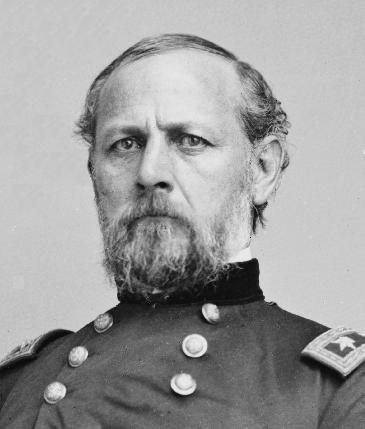

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges