|

Lee Decides to invade the North

After the Confederate humiliation of Hooker's Union troops at

Chancellorsville (early May), Lee seemed to take the attitude that the

Confederacy's best weapon was its audacity. The fighting spirit

of the Southern armies had certainly thus far acquitted the Confederacy

very admirably in its major military engagements with the North.

Lee also knew that war weariness was growing in the North. Voices

calling on Lincoln simply to let the South slip away were increasing in

number and in importance within the North. Lee hoped that one

more daring – and devastating – confrontation with the Northern Armies

might play so strongly into the hands of the peace party that the North

might be ready for terms acknowledging the independence of the Southern

states.

Thus he decided to strike deep into Northern territory with his Army of

Northern Virginia. On June 6th Lee began moving his forces out of

the Chancellorsville- Fredericksville area, leaving one of his three

corps (Hill's corps) behind to prevent Hooker's troops from crossing

the Rappahonnock and following the Confederates north. He wanted

as much as possible to keep his movements – and his intentions – hidden

from the North.

With his other two corps (Ewell's and Longstreet's) he began his move

to the northwest in order to cross the Blue Ridge mountains and move

northward through the Shenandoah Valley.

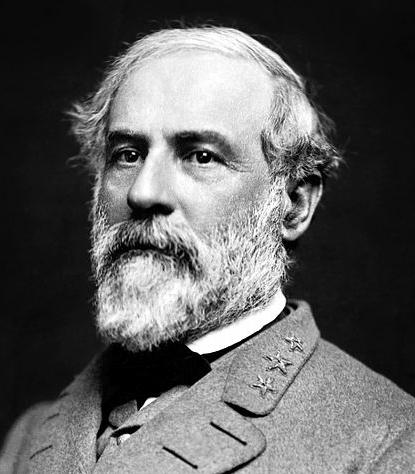

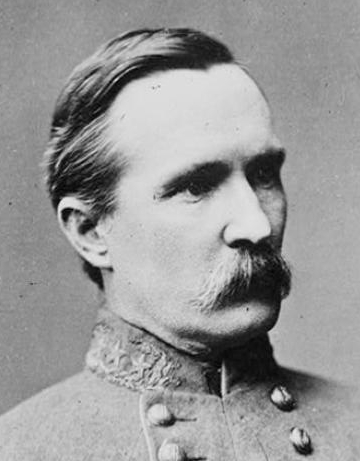

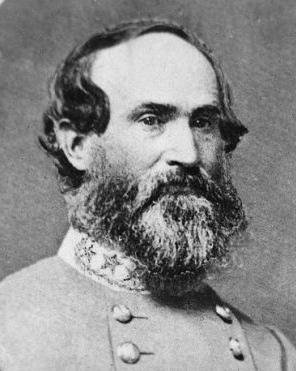

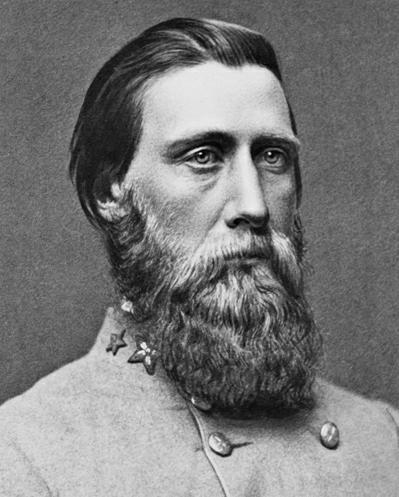

Generals Joe Hooker and Robert E. Lee

Brandy Station (June 9)

But a surprise awaited the Confederates when on June 9th, Hooker's

cavalry corps (under the command of Gen. Pleasanton) encountered the

Confederate cavalry corps (under the command of the almost legendary

Jeb Stuart). Stuart's horsemen had been gathering at Brandy

Station, readying themselves to accompany Lee's main forces in their

move to the North.

Hearing news of the gathering, Pleasanton had taken the initiative to

attack Stuart – and came very close to defeating Stuart with his

unexpected assault. The battle ended finally when Pleasanton

called his troops to a retreat.

Though Stuart had certainly not lost the battle – neither had he won

it, and his enormous pride suffered terribly from the humiliation of

not being able to live up to his reputation for victory. The

consequences of this otherwise minor action would ultimately be very

significant: Stuart, sensitive to the need to restore his

tarnished reputation, would become more focused on securing daring

exploits for himself and his men – than on following the explicit orders

of Lee to provide close protection to Ewell's right flank as the

Confederate army moved northward – and to stay in close touch with Lee

so that he would know constantly the exact whereabouts and movements of

the Union army. Indeed, at the crucial moment when later Lee

would encounter the first elements of the enemy in the North

(Gettysburg), the whereabouts of Stuart (who was off conducting raids

in the Pennsylvania countryside) would be a total mystery – leaving Lee

to have to guess blindly about the placement and size of the Union army

that was gathering to fight him.

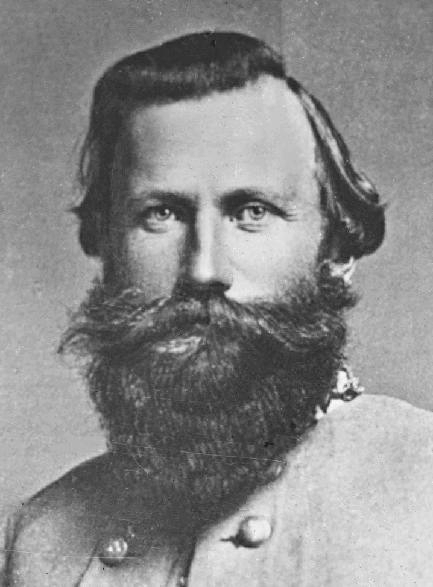

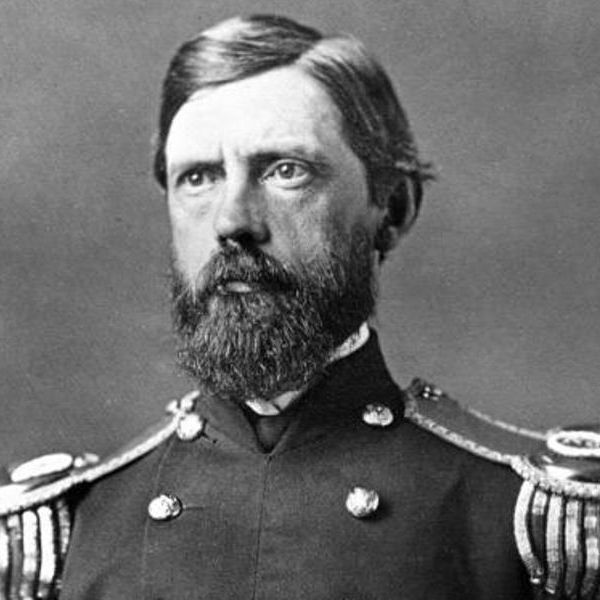

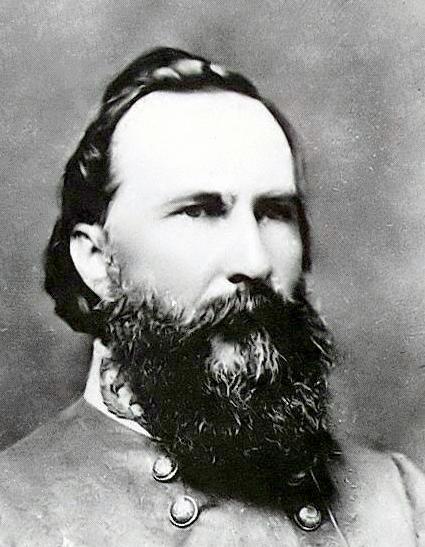

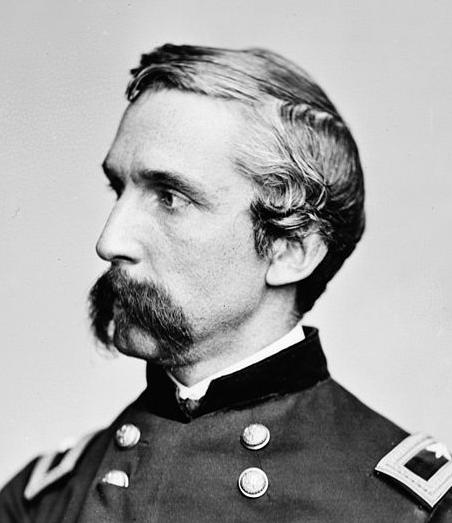

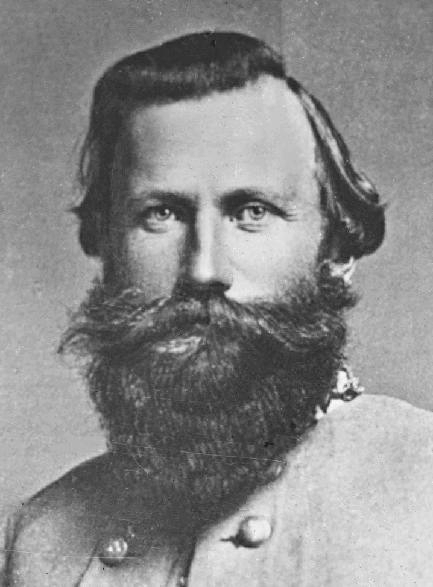

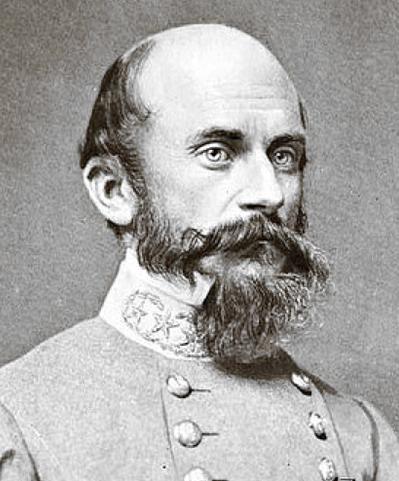

Confederate Generals J.E.B.("Jeb") Stuart and Richard S. Ewell

The Confederates move north rapidly (mid / late June)

On June 14th Union troops were caught by surprise and overwhelmed at

Winchester and further north at Martinsburg by Ewell's Corps. The

following day Ewell reached the Potomac, Longstreet's Corps and

Stuart's Cavalry were moving northward along the east side of the Blue

Ridge, and Hill was beginning his pullout from Fredericksburg in order

to join the rest of the Confederate army moving north.

The Union General Hooker however was not sure of what to make of the

reports of these Confederate movements. When he first realized

that only Hill's troops remained across from him in Fredericksburg he

wanted to attack Hill – and then move south to seize Richmond while Lee

was away in the North. But Lincoln commanded Hooker to go after

Lee's army instead, insisting that seizing Richmond without having

defeated Lee would be a meaningless victory – and would leave the North

unprotected. So Hooker began to move North to follow Lee, and to

protect Washington, if that was Lee's objective.

Along the way there were a number of Union cavalry skirmishes with

Stuart to the east of the Blue Ridge, at and around Middleburg (Aldie,

Middleburg and Upperville). But these did little to either slow

up Lee – or give Hooker any indication of what the Confederates were up

to.

It became more obvious that Lee was attempting a daring strike into the

previously unchallenged North as Ewell's troops crossed rapidly through

Maryland and entered Pennsylvania, where they attacked Chambersburg and

then began to spread throughout the countryside in a hunt for

supplies. Part of Ewell's Corps, under the division commander

Jubal Early, moved eastward from Chambersburg, to Gettysburg, and then

beyond to York – even reaching the Susquehanna south of Harrisburg on

the 29th of June. At the same time, two other of Ewell's

divisions, under Robert Rodes and Edward Johnson, moved north from

Chambersburg, entering Carlisle unchallenged. Harrisburg now

found itself threatened from the South and the West by Ewell's Corps.

Also Longstreet's and Hill's two corps had reached Chambersburg by the 27th and then turned eastward toward the Cashtown pass.

Consternation in the Union ranks: Meade replaces Hooker

The news that Lee had crossed the Potomac and had even entered

Pennsylvania finally (June 25th) led Hooker to move his army northward

from Virginia into Maryland, in the direction of Frederick.

Meanwhile the Pennsylvanians were gearing up to provide defense for

their capital by rallying the Pennsylvania militia.

It was at this moment (June 27th) that Hooker, in a fit of pique,

offered to resign his command – only to have Lincoln immediately accept

the proposal. Lincoln turned quickly to replace him with General

George Meade, a rather unassuming, though capable general. On the

following day, June 28th, Meade was stunned to learn of these

developments. But given the urgency of the moment, he had no time

to quibble or protest. As the new commander of the Union's Army

of the Potomac, he had to move quickly to prevent a catastrophe from

happening.

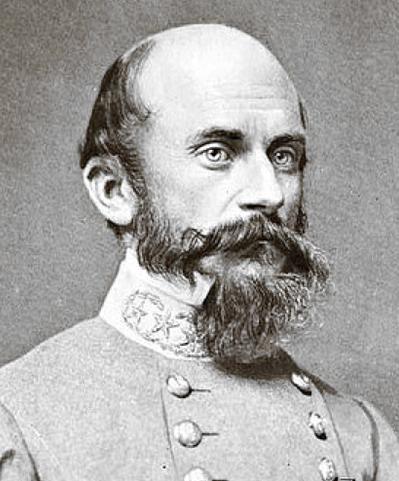

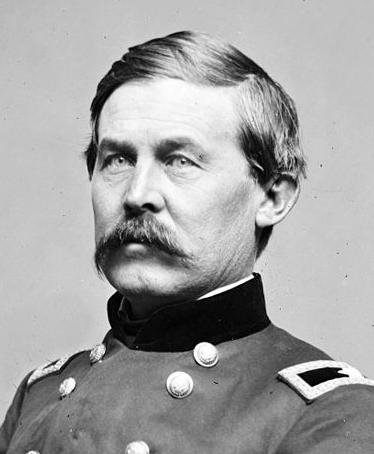

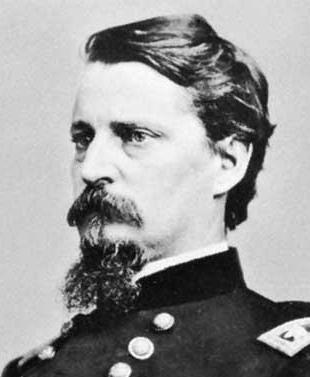

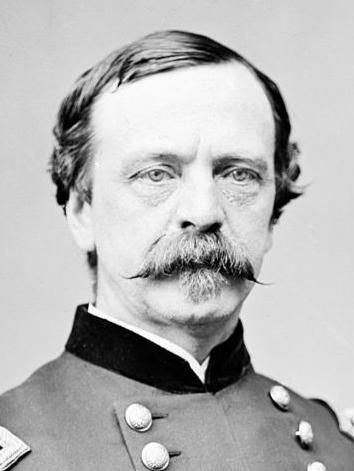

Union Generals George Meade and John Buford

June 30: The first Union-Confederate encounter at Gettysburg

It was Meade's intention to set up a defensive position for his army in

Maryland just south of the Pennsylvania border along Pipe creek, in

order to protect Washington and Baltimore. But events beyond his

control would soon draw Mead northward into Pennsylvania to the

crossroads town of Gettysburg.

Union cavalry under General Buford were scouting the Gettysburg area to

the north of the main Union army in an effort to locate Lee's army,

when they ran into the some troops from Hill's Corps headed toward

Gettysburg from Chambersburg in search of shoes! The

Confederates, in spotting Buford's forces, turned back to Chambersburg

– and reported the presence of a sizable number of Union troops just

to the northwest of Gettysburg.

Where was Jeb Stuart?

Jeb Stuart was supposed to be doing for the Confederates what Buford

was doing for the Union: locating and reporting back to headquarters

the size and disposition of the enemy. But Jeb Stuart had lost

contact with the main Confederate army weeks before when, rather than

follow Lee closely (as he had been ordered), he headed off to the

northwest, supposedly to put himself between the Union army and

Washington DC. His intention was for this act of bravado to put

the Union army in confusion – as it would supposedly be forced to

choose between following Lee northward and drawing back to the south to

protect its capital. But The Union army showed little interest in

Stuart and had stayed focused on its pursuit of Lee.

Consequently, as the Union army continued to move northward, its

position between Stuart's Confederate cavalry and Lee's main army kept

Stuart from being able to link up or even contact the main Confederate

force. Indeed, not only did Lee not know what Stuart was up to,

Stuart had no idea of what was happening with Lee – or the fact that

the Union and Confederate armies were headed on a collision course at

Gettysburg. Stuart continued to wander around the Pennsylvania

countryside oblivious to Lee's desperate need for cavalry

intelligence – until the battle at Gettysburg was well

underway. Consequently Lee had to make key initial decisions on

where and when to deploy his forces against Meade – without

any solid information about Meade's position.

July 1: The initial clash northwest of Gettysburg

The next day, July 1st, Hill sent

troops

from Gen. Heth's division back to Gettysburg, initially only to scout

out the Union strength (Lee had given explicit instructions that no

actual fighting was to take place until he could get all of his army

assembled outside Gettysburg, as it moved in from different points of

convergence (west, north and northwest). But Lee's plans, as

Meade's, were also overtaken by unanticipated circumstances at

Gettysburg.

Heth's Confederate reconnaissance forces coming down the Chambersburg

Pike and Burford's dismounted cavalry, in position on McPherson's Ridge

just west and north of the town of Gettysburg, inevitably drew

fire on each other as they again met, this time directly. Neither

side was willing to withdraw, which was the only way to avoid action

(which Lee was very clear about avoiding until all his troops were in

place). The battle thus was joined by advanced troops of both

armies just outside Gettysburg, a situation which neither Meade nor Lee

had wanted.

Generals Henry Heth and John Reynolds

Generals Henry Heth and John Reynolds

This conflict on the morning of the 1st was further intensified by the

arrival at Gettysburg from Emmitsburg of Union 1st Corps General John

Reynolds, who had not yet been told of Meade's plan's to form a

defensive line in northern Maryland – but who on the other hand had

been told by Buford about the previous day's encounter with Confederate

troops. Seeing Buford's cavalry trying to hold off a gathering

Confederate force, Reynolds quickly returned to the advance column of

his troops in order to hurry them along in joining up with a

hard-pressed Buford. (Reynold's 1st Corps formed the west-most

wing of a Union line which spread 30 miles from Emmitsburg in the west

to east).

But just as his troops (including the fabled Iron Brigade) began to

arrive and he was placing men and canons in positions across the

Chambersburg Pike, Reyolds was shot and killed. This was a

sign of things to come.

The battle raged back and forth as new troops filed in from either

side. The situation was confusing and a huge loss of life and

capture of enemy troops resulted. As Confederate reinforcements

were closer at hand, the situation turned increasingly in favor of that

side. The first of Ewell's Corps (Rodes Division) began to arrive

from the north and soon the Union 11th Corps found itself vastly

outnumbered. In the meantime the Union 1st Corps was being

overwhelmed to the West by Hill's Corps (Heth's Division) as the

Confederate troops were now sufficient in number to begin to swing

around the Union's southern flank – and threatened to encircle

them. The Iron Brigade tried to hold its position on McPherson

Ridge – but the result was the near total destruction of this highly

reputed brigade.

Late in the afternoon, the Union 1st and 11th Corps were ordered to

fall back through the town – to retreat to Cemetery Ridge

just to the southeast of the town, where Union canon and troops were

being assembled as they arrived from the south. The retreat was

orderly but nonetheless not fully successful, as many Union troops were

fully encircled by the Confederates before they could move out.

Approximately 3,600 Union troops were thus captured by Confederates that

day.

At the head of the Union troops arriving from the south was Major

General Winfield Scott Hancock, who had been ordered by Meade to get to

Gettysburg as fast as possible and begin to lay out a position for the

rest of the arriving Union troops to occupy. It was Hancock's

decision to make Cemetery Hill the centerpoint of the Union

position. As new troops arrived they were placed either to the

south of this point along Cemetery Ridge, to face Hill's Corps coming

in from the west – and along the southeast across Culp's Hill, to face

Ewell's Corps coming in from the east and northeast.

For a moment Ewell was in a position that if he had forced the issue

(as Gen. Early requested) he might have successfully challenged the

Union position atop Cemetery Hill before more Union troops arrived to

take position there. But Ewell hesitated (he was still stinging

from Lee's anger at having started the action before Lee was fully

prepared to do battle) and the opportunity was lost.

Thus did the first day's battle end.

Generals Winfield Scott Hancock and Jubal Early

July 2: Confederate Attacks on the Northern and Southern Wings of the Federal Line

The

next morning, July 2, Lee and Meade's armies were rapidly pouring into

Gettysburg. Meade decided to take advantage of the heights that

his army had moved up to and dug in to await Lee's next move.

Lee meanwhile situated the bulk of his army in the heights of Seminary

Ridge a mile to the west of the Union position. Between the two of them

was a wide expanse of open field that someone was going to have to

cross to get to the enemy. Longstreet advised Lee to hold their

defensive position. But Lee felt that the winning tactic for the

South had always been to press the attack. And to press the

attack was what he was determined to do – even though the Union forces

were quickly getting well dug-in in the heights across the way

Lee determined that he would attack the extremities of the Union line,

directing Ewell to strike the northern end of the Union line at Culp's

Hill – and Longstreet, with his larger forces, to hit the southern end

of the Union line along Cemetery Ridge.

Generals James Longstreet and Daniel Sickles

At the southern front, the Confederate situation was greatly aided by

the foolish decision of General Sickles to bring out his III Corps from

the heights to meet the Confederates under McLaws near a peach orchard

below – badly exposing his men to Confederate encirclement. He

subsequently had to fall back – with great losses in fighting in the

wheatfields behind the peach orchard, throwing part of the Union

position into disarray.

Generals John Bell Hood and Joshua Chamberlain

The Confederates under Hood tried to swing south around behind Sickles

in a race to seize the undefended heights of Little Round Top.

Many were slowed up or stopped in fierce hand to hand fighting in the

boulder-strewn Devil's Den at the foot of Little Round Top. Other's of

Hood's Division tried to sweep around to the south and capture the hill

from that direction. But a small number of Union troops (among

them, the 20th Maine under Chamberlain – brought to today's attention

through the movie Gettysburg), reached this strategic position first

and held it – to then be joined by more Union troops who gathered

there. Repeated Confederate assaults on Little Round Top could not

dislodge the Union soldiers dug in there. With Little Round Top

still held by Union troops, they could make no further advances against

the Union's southern flank.

Meanwhile at the other end of the line of battle, to the north, Ewell

was no more successful in dislodging the Union troops from their

position atop Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill.

July 3: Pickett's Charge on the Union Center

On

the next day, July 3, Lee made the decision to assault the center of

the Union line along Cemetery Ridge. He thought that if he could

break through this position, he could cut the Union army in two and

swing in behind their undefended backs. But to do so, he would

have to cross an open and thus unprotected plain a mile wide to reach

the Union forces well dug in along the low ridge which protected the

Union center.

He hoped that heavy bombardment of that position by cannon might weaken

that position sufficiently to reduce the dangers he faced there.

So from 1:00 to 3:00 in the afternoon the Confederates undertook the

massive expenditure of cannon shell and powder against the Union

position. During this massive barrage the Union troops did not

really respond – but held their fire. In the end, the Confederate

fire and smoke succeeded only in exhausting the supplies of the

Confederate artillery – and in little else.

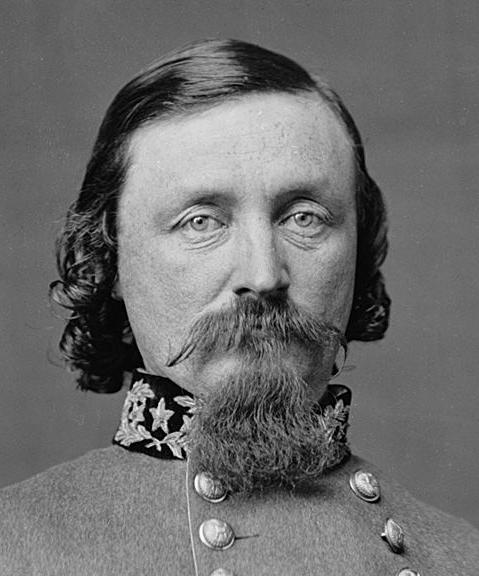

General George Pickett

General George Pickett

Then in a long line the Confederates began to move their troops slowly

across the open fields (in what came to be widely known as "Pickett's

charge") toward Hancock's Union position – in particular

toward a single point of convergence known today as the

"Angle." Union rifle and cannon fire ripped through the

Confederate ranks. Still on they came, led by General Armistead, who

had moved to the front his officer colleagues, who were shot down one by

one. He tried to preserve an orderly advance as they continually

fell before the Union fire. They reached the Angle – but by this

time it was heavily reinforced. He could not break through – and

himself fell, mortally wounded. Finally the Confederates were

faced with no other option but to fall back, having failed to break the

Union lines anywhere. Lee knew that he had lost the battle for

the North that day.

Meade Lets Lee Escape to Virginia

On the following day, July 4, Lee order the retreat of his army – back

toward Virginia. Meade, like the generals before him, did nothing

to pursue the retreating enemy. They were exhausted.

Everyone was exhausted.

It was a grand disaster for the South – and Lee recognized immediately

that he had gambled the lives of his men foolishly. He lost

28,000 of his 70,000 troops. But it had been costly for the North

as well. Meade had lost 23,000 of his army of 90,000.

Nonetheless, it was Lee, not Meade, who had been broken by this

action. Lee would never be able or willing again to try an

assault on the North. Henceforth, the war would be a process of

the South trying to protect itself from invading Northern armies.

This then marks the turning point of the War.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges