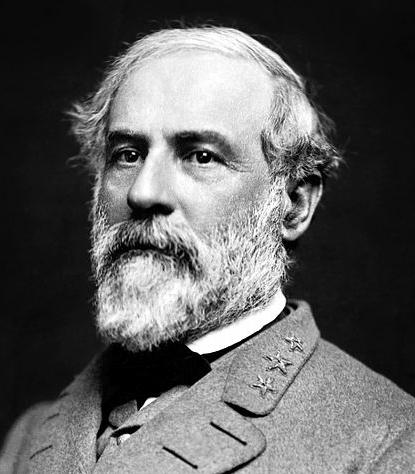

After Chancellorsville, Lee understood that his

best strategy would be once again to take the war into the North and

conduct a bold strike against the Northern army, which in turn would

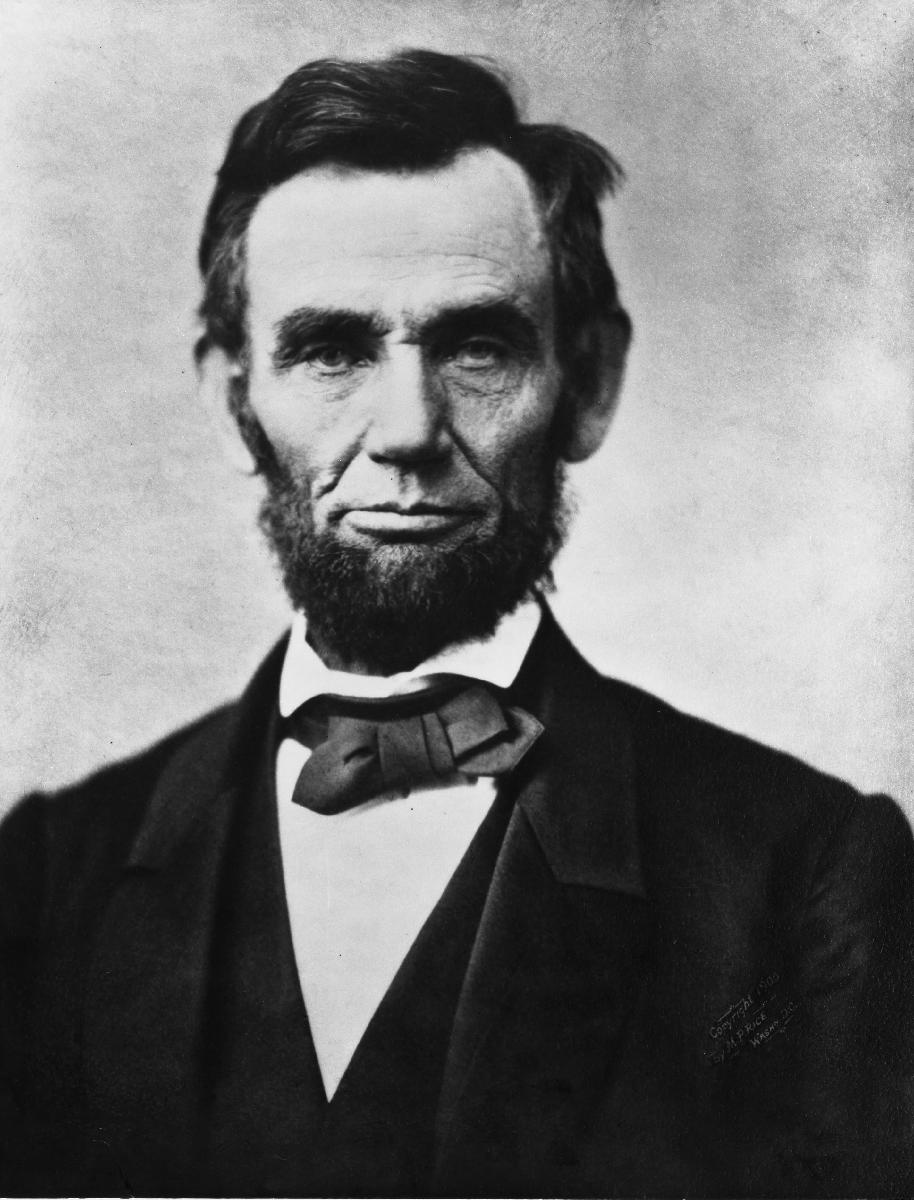

likely force Lincoln to have to give in to the rising voices in the

North demanding immediate peace with the South.

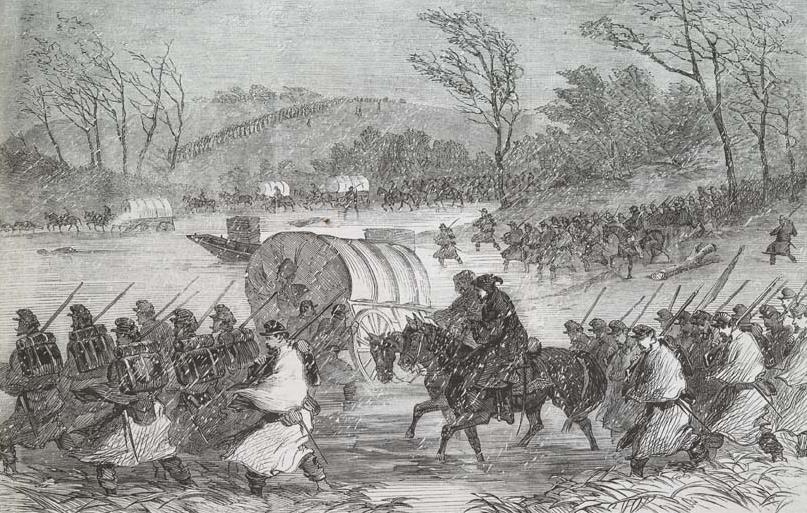

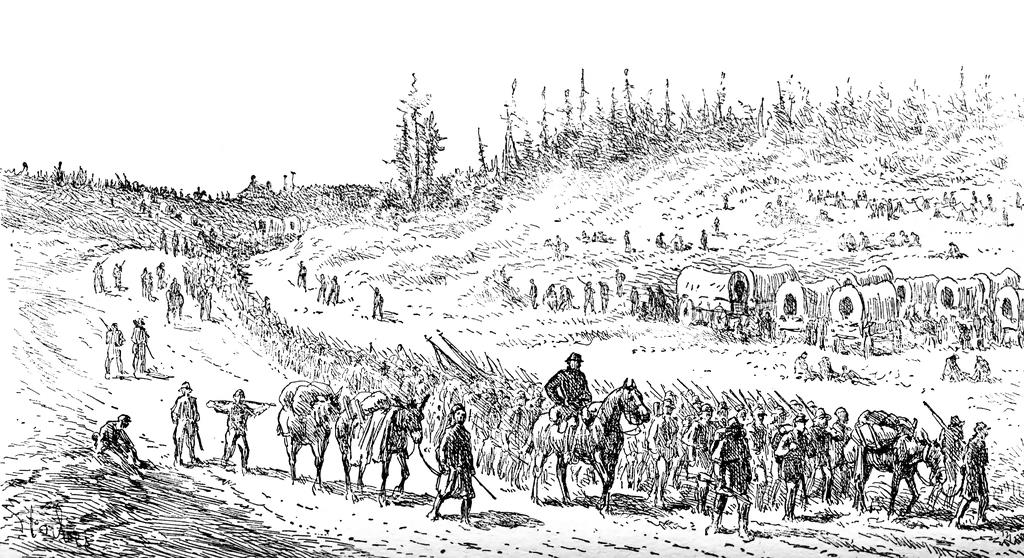

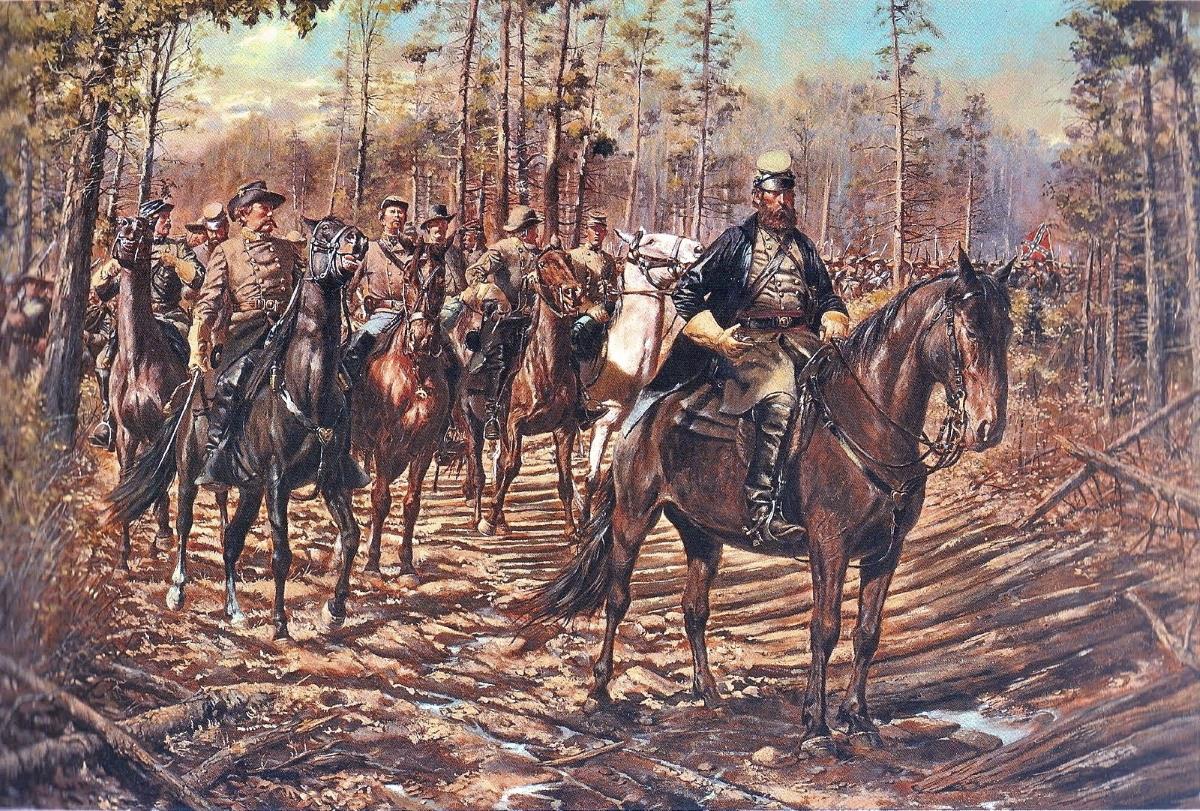

When Meade got his new orders to take

command of the Union Army of the Potomac, Lee already had a number of

his troops in southern Pennsylvania, with the Confederate cavalry

leader Jeb Stuart raiding the countryside. It looked as if Lee intended

to grab the Pennsylvania capital, Harrisburg, so Meade gathered his

forces and headed northwest from Maryland to intercept him. On June

30th, at the small Lutheran seminary town of Gettysburg, forward

elements of the two armies met.

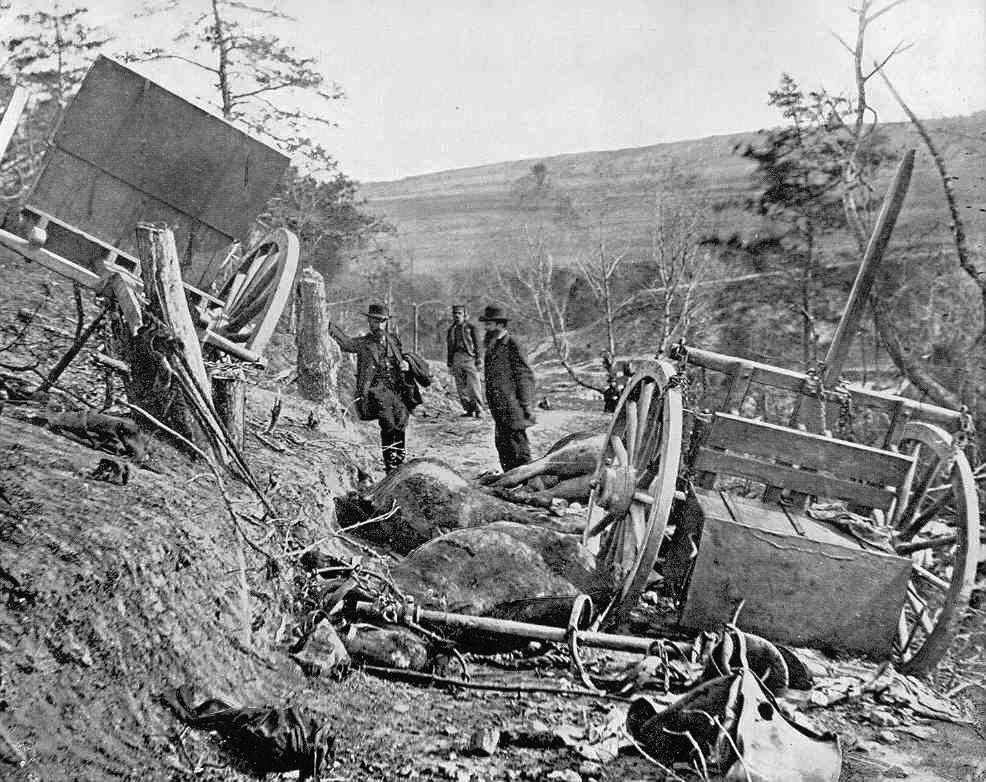

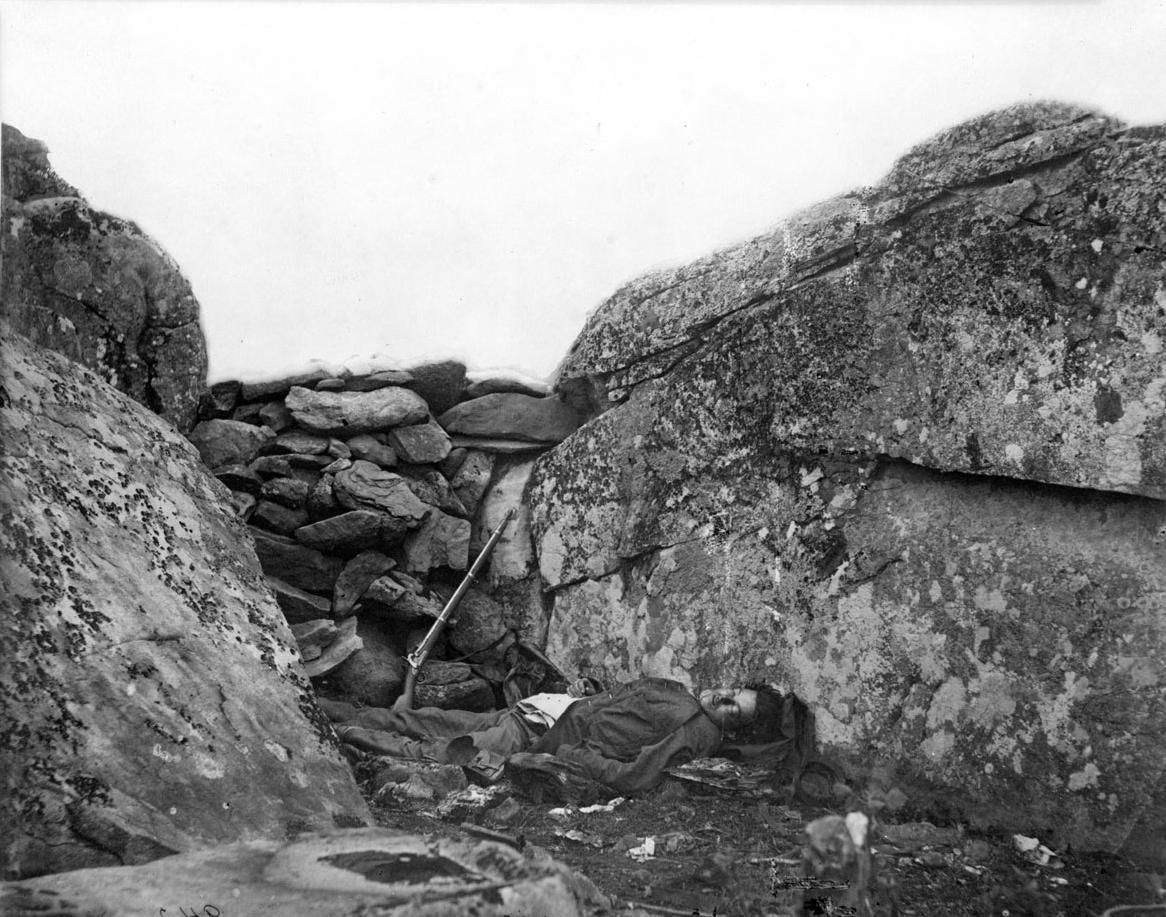

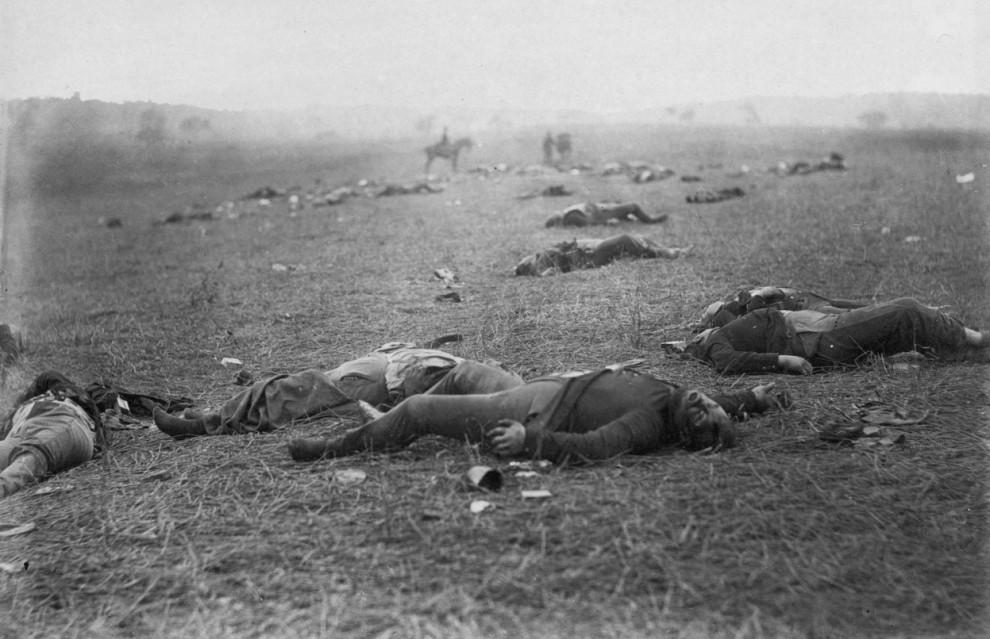

For the next three days the two armies

fought each other, the Union armies holding defensively the upper

grounds and the Confederate armies attempting to dislodge or even

surround the well-entrenched Union position. This time the immense

boldness of Lee did not suffice to carry the day, despite the enormous

effort Lee applied to the task of overrunning the Union position. Even

a massive frontal assault across one mile of open field produced merely

huge Confederate losses. Finally, on July 4th, Lee ordered the retreat

of his army – back toward Virginia.

Tragically, Meade did nothing to pursue

the retreating enemy. He and his troops were exhausted. But so were

Lee's. Once again, like the generals before him, Meade could not think

past the issue of the battle at hand and understand that he had a war,

not just a battle, to win. By letting Lee escape back to Virginia, he

had let slip by the opportunity to end the war then and there. Lincoln

was pleased with Meade's victory, but was upset that Meade had missed

what to Lincoln was an obvious opportunity to crush Lee's army and end

the war.

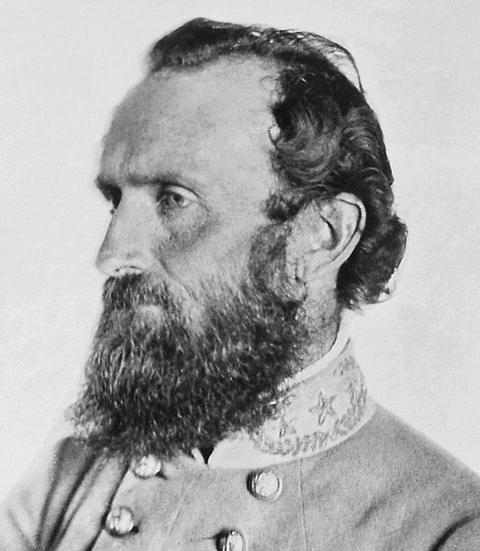

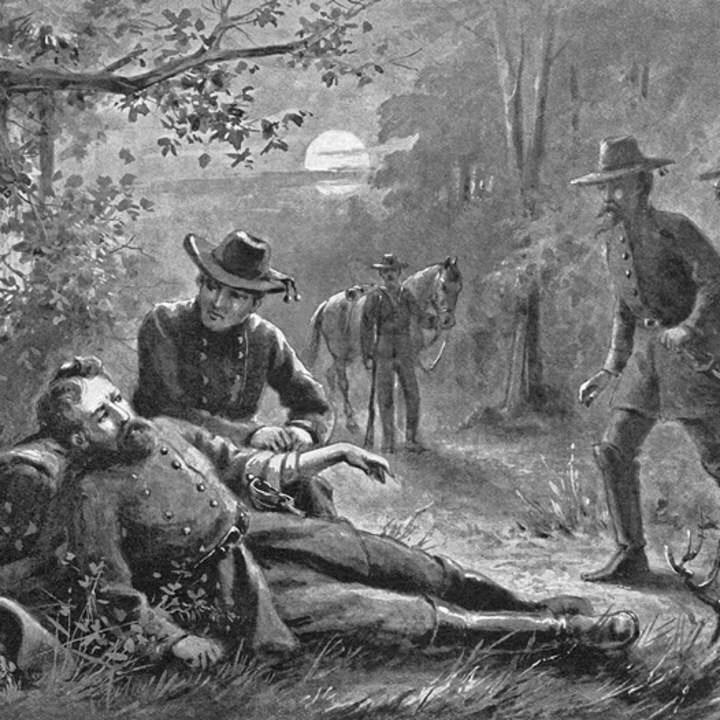

Yet it was still a grand disaster for the

South – and Lee recognized immediately that he had gambled the lives of

his men foolishly. He lost 28,000 of his 70,000 troops. But it had been

costly for the North as well. Meade had lost 23,000 of his army of

90,000. Nonetheless, it was Lee, not Meade, who had been broken by this

action. Lee would never be able or willing again to try an assault on

the North. Henceforth, the war would involve the South trying to

protect itself from invading Northern armies. Gettysburg (and

Vicksburg) then marked the turning point of the War, although at the

time this was not widely understood in the North.

A second attempt at Fredericksburg (January)

A second attempt at Fredericksburg (January)

Mounting Opposition to the War

Mounting Opposition to the War

Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg (May 1-6)

Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg (May 1-6)

Gettysburg

(July 1 – 3)

Gettysburg

(July 1 – 3)

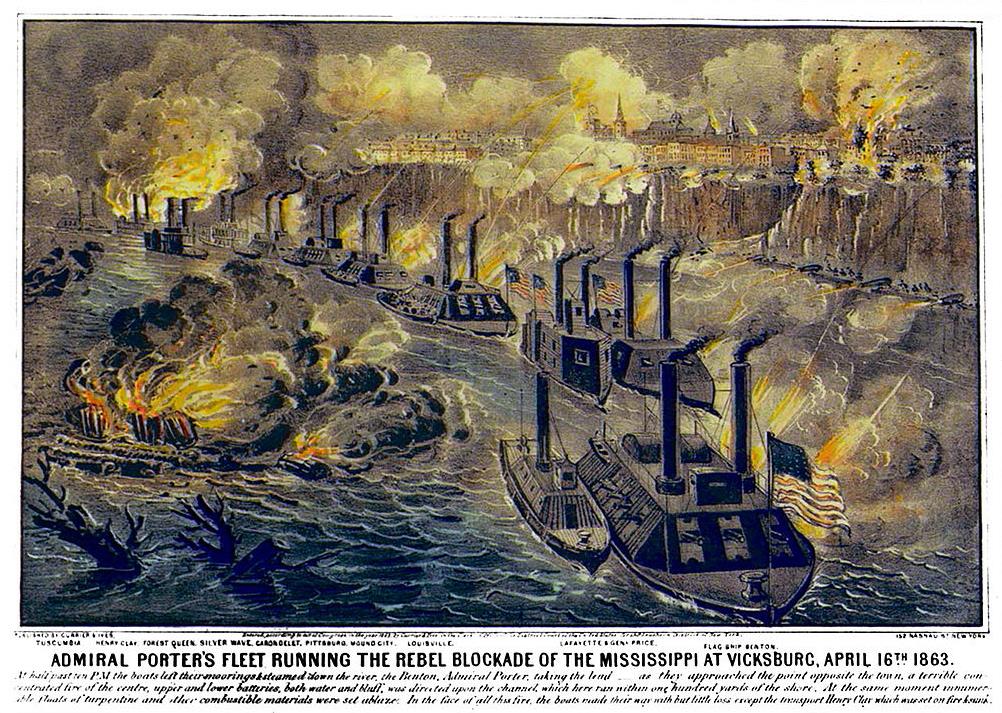

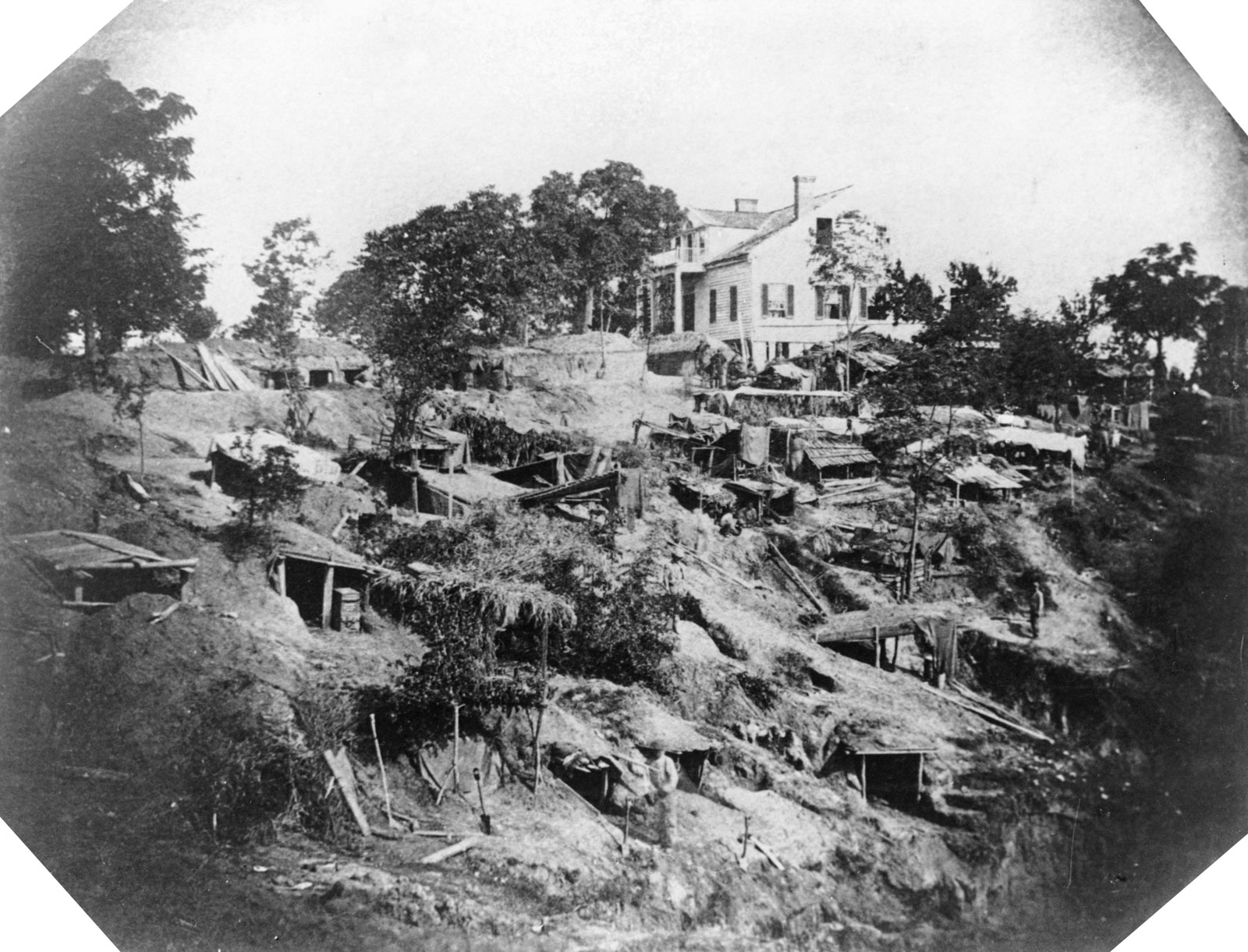

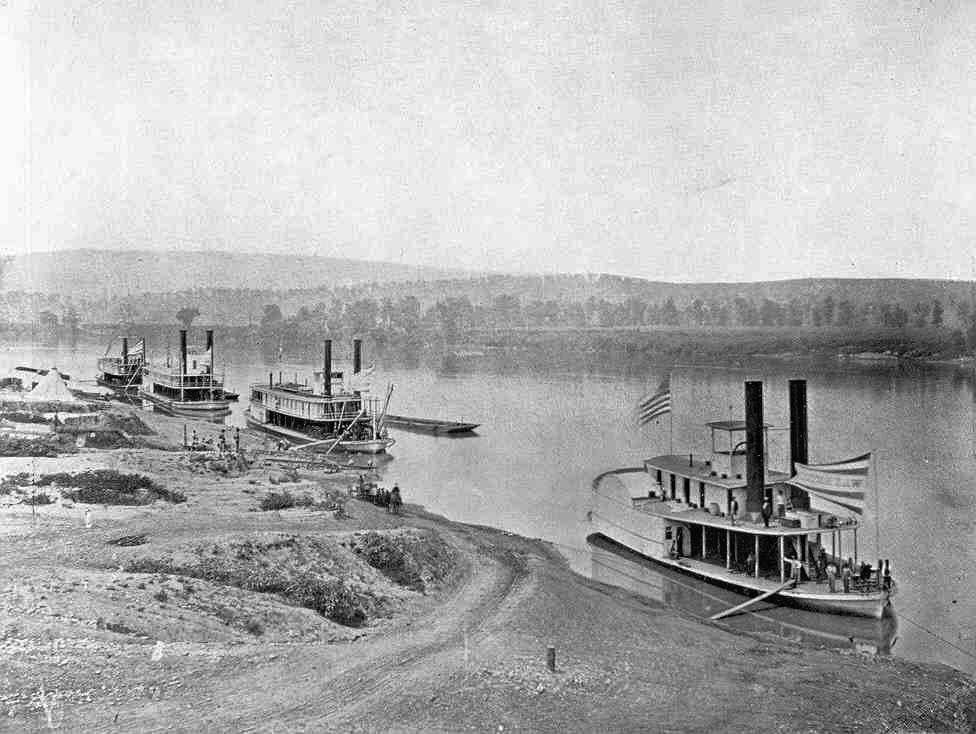

Vicksburg

Vicksburg

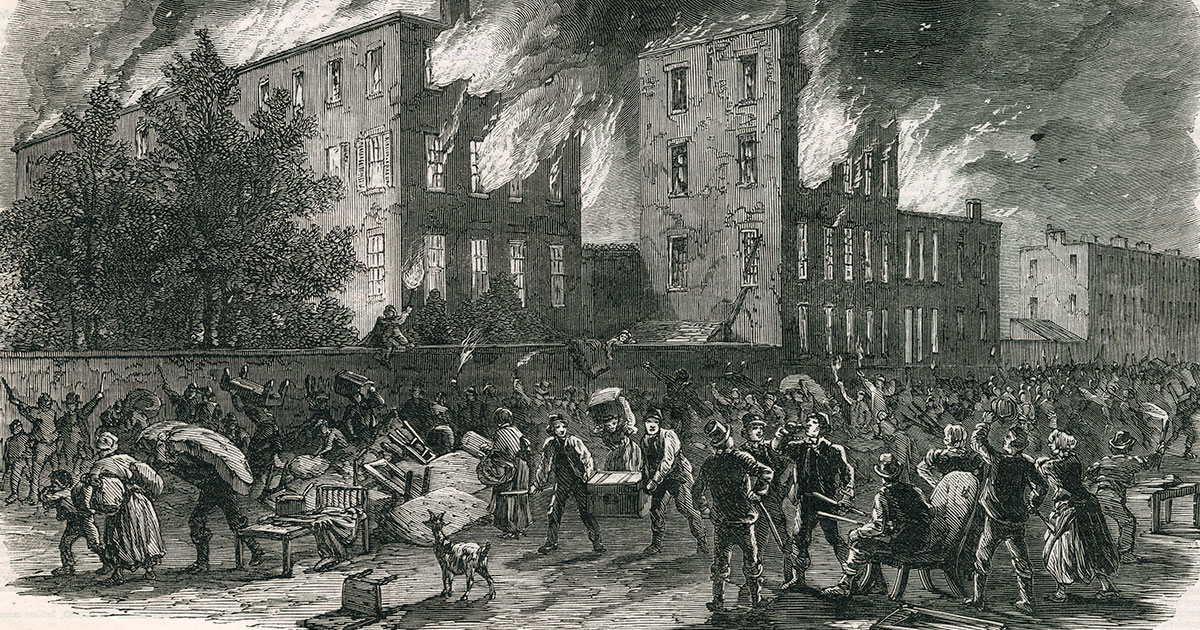

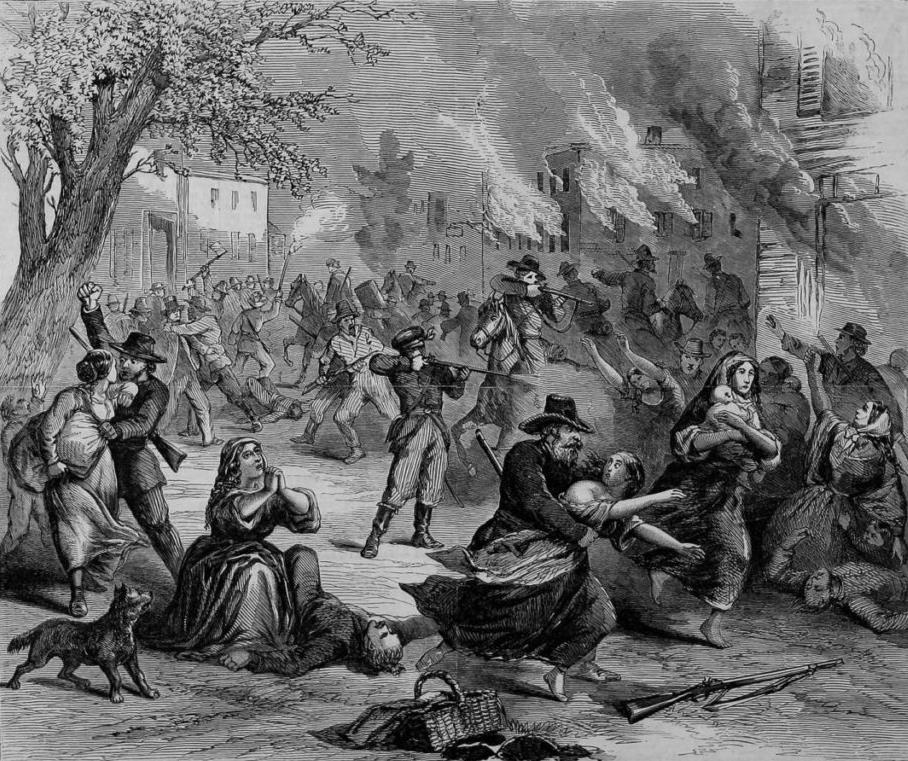

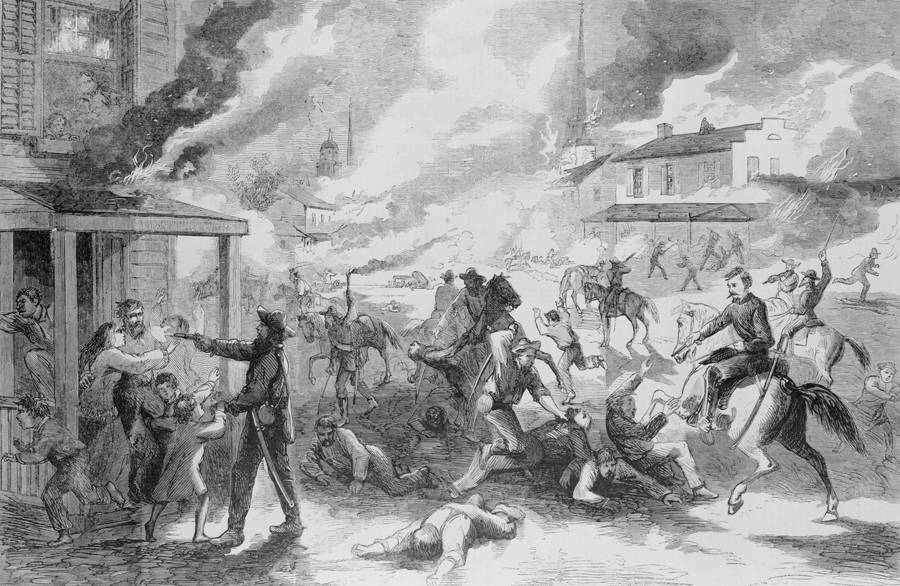

Quantrill's massacre at Lawrence, Kansas (August 21)

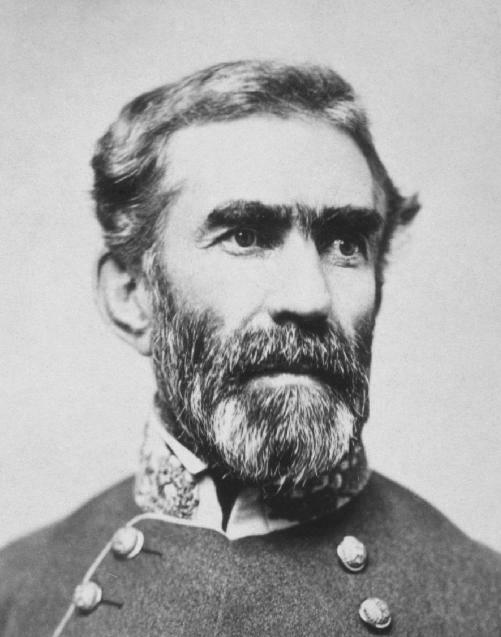

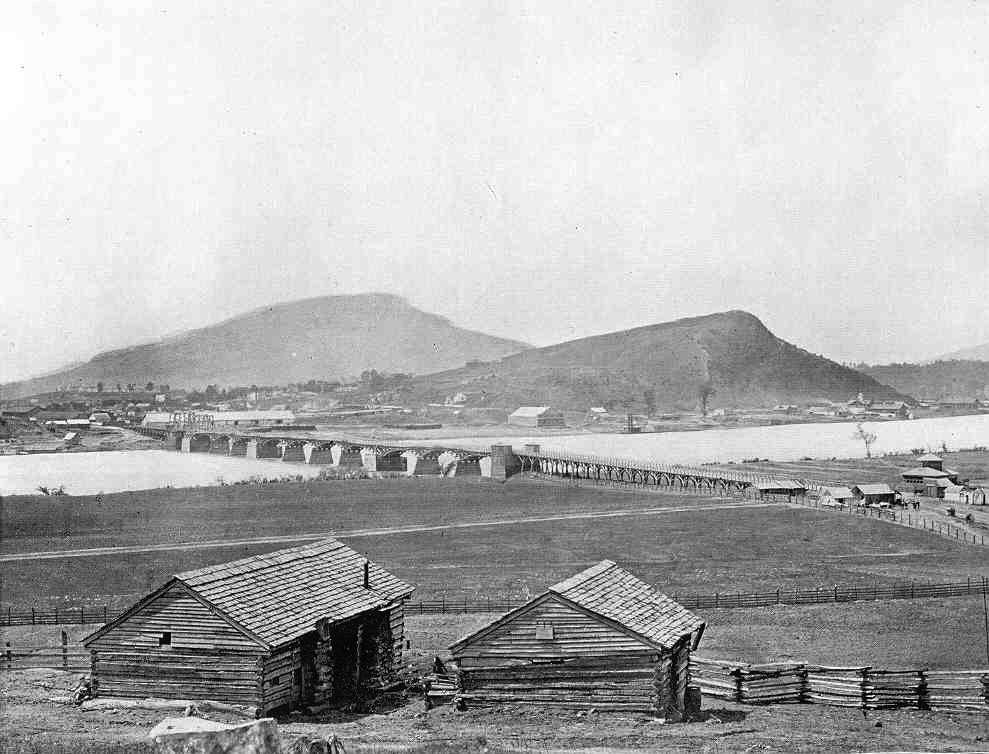

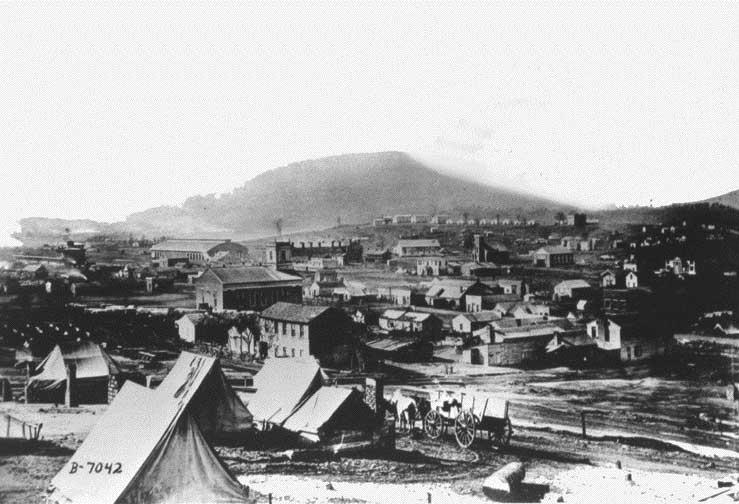

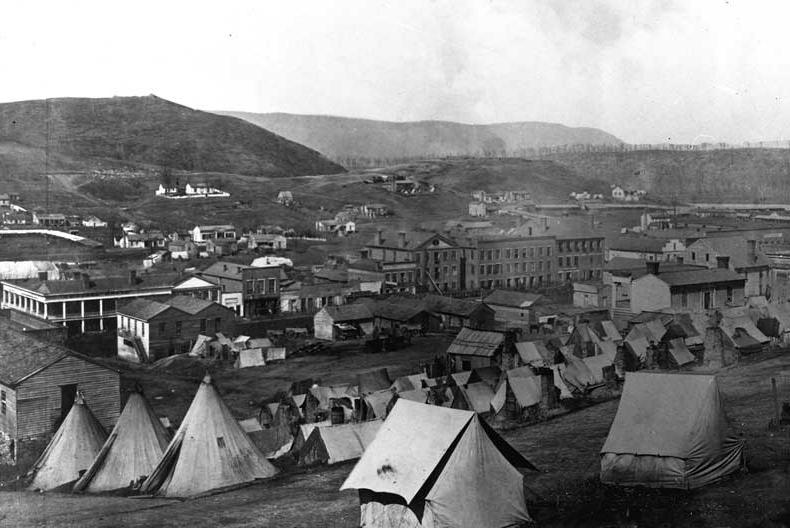

Quantrill's massacre at Lawrence, Kansas (August 21) Chickamauga

and Chattanooga (September-November)

Chickamauga

and Chattanooga (September-November)  Lincoln delivers his Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863)

Lincoln delivers his Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges