|

CONTENTS  Chickamauga

(September 19 – 20) Chickamauga

(September 19 – 20)

Chattanooga

(November 24 – 25) Chattanooga

(November 24 – 25) |

|

CONTENTS  Chickamauga

(September 19 – 20) Chickamauga

(September 19 – 20)

Chattanooga

(November 24 – 25) Chattanooga

(November 24 – 25) |

|

| Action

at the central front in Tennessee had been fairly quiet during the

first half of the year after the Murfreesboro battle in January.

Union General Rosecrans had kept the Army of the Cumberland encamped

and did not attempt to engage the Confederate armies under General

Bragg. But concern in Washington mounted that Bragg might pull out of

the inactive theater and join Johnston's Confederate forces confronting

Grant in Mississippi. Thus in late June Rosecrans finally stirred – and

began to come after Bragg, pushing his Confederate army back 80 miles

through rough terrain to Chattanooga, along the Tennessee River just at

the Tennessee border with Northwestern Georgia. Under further pressure from Washington, Rosecrans began to make a move simultaneously on Knoxville and Chatanooga in mid-August. Burnside moved his Union armies 100 miles north to Knoxville – a town of considerable Union sentiment. And Rosecrans himself led the attack of Bragg's forces at Chattanooga. At Knoxville, the outnumbered Confederates surrendered without a fight. On September 3, Burnside and his Union army took over the town. Rosecrans' attack on Chattanooga also went almost effortlessly. As the Union forces approached Chattanooga, Bragg sensed that his supply line to the Confederacy was threatened by a Union flanking movement. Thus Bragg made the decision to abandon Chattanooga and retreat South into the Georgia mountains. Thus on September 9 Rosecrans' troops entered the town unopposed. But the South had already noticed the danger to their position in the mid-South posed by a Union army amassing in southern Tennessee and therefore had been making preparations to counter the growing Union pressure there. Thus they had pulled Longstreet and 20,000 of his troops out of the Army of Northern Virginia and on September 9, just as Rosecrans was entering Chattanooga, began to send them by rail to link up with Bragg. Also other confederate divisions were converging on Bragg's camp from all directions. Unknown to Rosecrans, Bragg would soon increase his army to 70,000 troops, seriously outnumbering Rosecrans' 57,000 Union troops. Rosecrans, having so easily taken Chattanooga from Bragg, meanwhile jumped to the wrong conclusion that Bragg's retreat was an indication of a demoralized spirit prevailing among the Confederate army. He thus eagerly and incautiously plunged southward into the densely wooded mountains of Georgia in pursuit of Bragg. Because of the difficulty of moving large numbers of men through this rough terrain and because he thought he was pursuing a broken Confederate enemy, his lines were scattered. He had no idea of what was waiting for him. He had not gone very far, just through a couple of narrow gaps in the ridge of mountains overlooking Chattanooga (Missionary Ridge), when on September 12th, he suddenly and unexpectedly came upon portions of a Confederate army firmly entrenched in the valley on the other side of this line of mountains at Chickamauga Creek, about 12 miles south of Chattanooga. Because of the denseness of the woods, it was difficult for the two sides to determine exactly what they had in front of them as an enemy. Bragg was in a superior position with his forces well in place, facing only the advanced units of Rosecrans' army. He had a grand opportunity to crush them at this point. But Bragg proved indecisive in the face of this opportunity. His actions against these first Union corps were hesitant and ineffectual. He was reluctant to move forward until Longstreet's troops arrived. Thus instead of pressing his tremendous advantage he sat there – day after day. This gave Rosecrans precious time to get his army reunited and organized – and to bring up more troops. Finally on September 19 Bragg struck what he thought was the northern flank of the Union army in the hope of cutting off its retreat northward to Chattanooga. But because of the confusion caused by the denseness of the forests they were fighting in, he had actually chosen to assault a more central and well defended portion of the Union lines – a position held by General George Thomas, a very capable Virginian who had stayed loyal to the Union. The battle raged back and forth and confusion reigned supreme. The fighting even continued through the night as nervous troops reacted to an enemy they could not see or size up. On the next day, Sunday the 20th, they clashed again – even more ferociously. By this time Longstreet had arrived and Bragg put these Confederate reinforcements along his left or southern flank. But the opening action of that day exploded along the northern flanks of both armies. By this time Rosecrans was sensitive to the possibilities of Bragg turning the Union position on the north and cut off the possibility of a Union retreat north back into Chattanooga – and also to the call of a very hard-pressed Thomas for reinforcements. Thus Rosecrans proceeded to move some of his forces northward in support of Thomas. But this was timed with the movement forward of Longstreet's newly arrived troops (of which Rosecrans was unaware) – just at the point at which Rosecrans had pulled reinforcements out of the line to help in the action further north. Longstreet thus charged ahead – to discover no Union forces in front of him. He had, in fact, split the Union lines in two. Longstreet then proceeded to devastate the southern half of the Union army, which panicked and fled (along with Rosecrans) through the gaps back to the road to Chattanooga. But the Union left or northern flank under Thomas held firm. He rallied about 25,000 troops and moved to a defensive position along a rocky horseshoe-shaped hill (Snodgrass Hill) – and proceeded to stand his ground (as he had been pretty much all day) against vastly larger Confederate forces. This permitted the relatively safe flight of the rest of the Union army back into Chattanooga. Finally at nightfall, as the day's fighting came to a close, Thomas (who had earlier been joined by additional troops from Granger's division) retreated from the field of battle – and Thomas, "the Rock of Chickamauga," moved his troops in orderly array back to Chattanooga. Though the battle amounted to a Confederate "victory," it was devastating – to both sides. The Union suffered 16,000 casualties; the Confederacy 21,000. Longstreet and other Confederate Generals urged Bragg to pursue the retreating Union army. But Bragg was exhausted, even in something of a state of shock given the severity of the battle. The Confederates, much to Longstreet's great disgust, therefore did not pursue. |

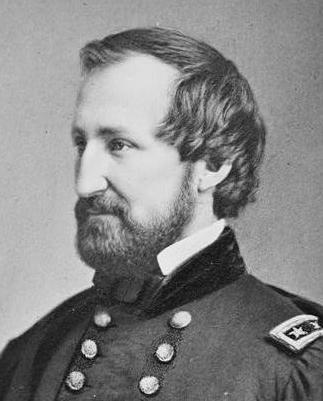

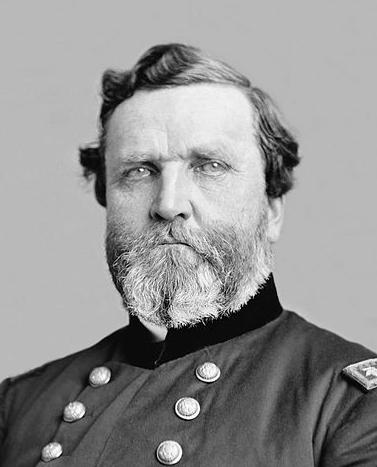

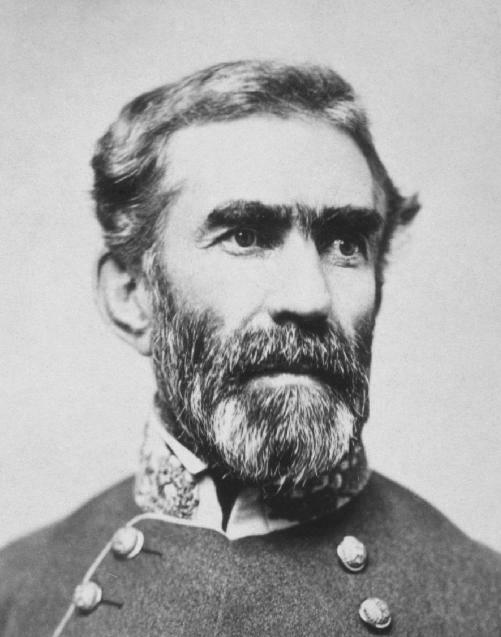

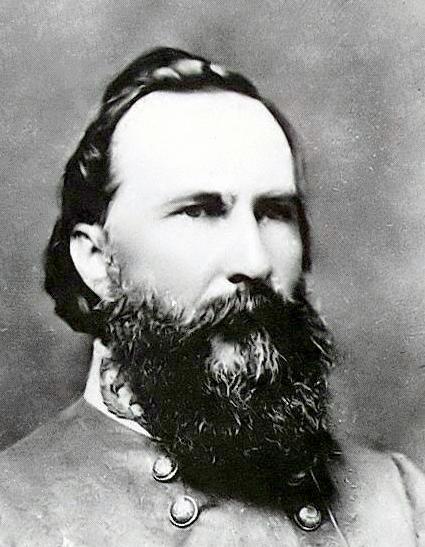

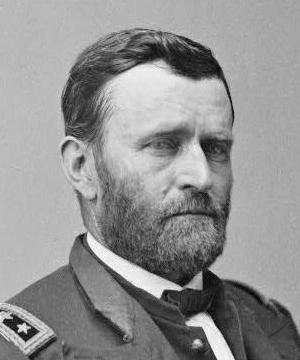

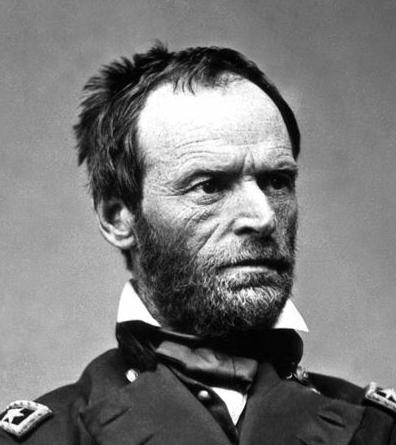

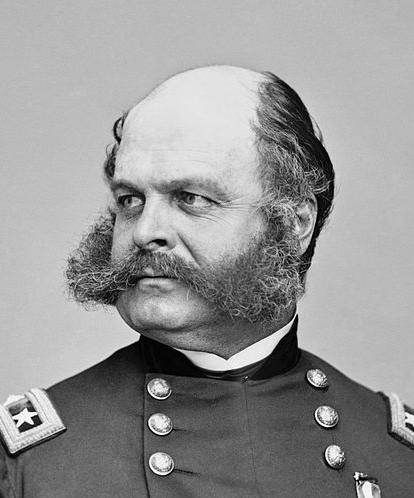

Union Generals

Rosecrans / Thomas   Confederate Generals Bragg / Longstreet |

|

| But

the Army of the Cumberland was actually in a captive position there in

Chattanooga, and thus Washington ordered troops brought in by train and

by boat to relieve Chattanooga. Troops were brought in from

Virgina (General Hooker) and from the Mississippi (General Sherman) and

placed under Grant, who was commissioned as commander of all Union

operations from the Alleghenies to the Mississippi. One of

Grant's first actions was to inform Thomas that he would take over

command of the Army of the Cumblerland from Rosecrans – and that he was

to hold Chattanooga at all costs. In order to bring men and supplies to a starving Union army in Chattanooga, Grant cleared the Tennessee River of enemy forces. To by-pass the more serious obstacle along the river just outside Chattanooga, Confederate-held Lookout Mountain, Grant established a short overland supply route to bring these men and supplies the last few miles to the town. Chattanooga was safe. Bragg, in the meantime, proceeded to dig in along a line which encircled Chattanooga from Lookout Mountain southwest of the town to the point where Missionary Ridge approaches the Tennessee River northeast of the town. So confident of his ultimate victory over any force sent against his impregnable position, Bragg had ordered Longstreet to move his 20,000 troops, one-third of Bragg's forces, on to Knoxville to attack Burnside and his 15,000 Union troops stationed there. This was upsetting news to Grant when he first heard the news. But in the end, Burnside easily held off Longstreet at Knoxville. Ultimately this move served only to weaken the Confederate strength at Chattanooga. Grant now turned his attention to the Confederates in the heights above the town. His plan was to use Hooker's troops to capture Lookout Mountain at the southern end of the Confederate lines and Sherman's troops to attack the other end of the lines at the north end of Missionary Ridge. Thomas's Army of the Cumberland, just having been humiliated by its defeat at Chickamauga and by its rescue from starvation by Hooker's and Sherman's troops, now was given the added humiliation of having to attack the center of the Confederate lines – positioned atop the 500-foot high cliffs of Missionary Ridge. There was, of course, no expectation that the troops would do anything except perform some sort of diversionary action at the foot of the cliffs in order to keep Bragg's forces from being concentrated on his two flanks. But there was very little that went according to Grant's plans. On November 24, the action started when Hooker charged Lookout Mountain and, outnumbering the Confederates 6 to 1, overwhelmed the small Confederate post there – in full view of the thousands who watched this spectacle from a distance. But that was the extent of the success of the planned effort. When Hooker then turned north to face the Confederates whose entrenchments closed a nearly 3-mile gap in the lowlands between Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, the Confederates refused to be dislodged. And Sherman found the Confederates at the northern end of the line to be no less resistant. They had to face hill after hill positioned with Confederate sharpshooters who made their advance painfully slow. By nightfall, Hooker and Sherman had made rather minor progress against the bulk of the Confederate army still occupying both the gap and Missionary Ridge itself, both its heights and the trenches they had built along its base. The next day, November 25, the Army of the Cumberland showed its true abilities. Grant's orders were for Thomas' men to advance to the base of Missionary Ridge and hold. Further orders would come at that point. But something took hold of the soldiers themselves that changed the whole course of the battle. They were hungry for a chance to prove themselves to the other soldiers that viewed them as being only very inferior troops. Thomas's men moved in a two-mile front up against the first line of Confederate trenches at the foot of the cliffs. But there could only be a brief rest for them there anyway for they were very vulnerable to the fire pouring down on them from above. So they moved forward, taking the next line of trenches – without awaiting further orders. The Confederates attempted to retreat up the cliffs. But Thomas's troops followed them, becoming wilder with each advance. And as others looked on in amazement, including the shocked Confederate troops at the heights of the cliffs, they just kept on moving up the cliffs – competing with each other to reach to top first – to find there a Confederate force that had become terrorized by the spectacle. The Confederate center melted away as men in gray fled down the slopes of the other side of Missionary Ridge. It was a rout. With a two-mile hole in the middle of the Confederacy's ranks, the situation became hopeless for the rest of Bragg's army. Thankfully for the Confederates, the Union troops were more in a mood to celebrate rather than pursue – and the rest of Bragg's army was able to make an escape from this fired-up Union army. Chattanooga would not be threatened again by the Confederacy. It was a disaster for Bragg's army, although both sides suffered big losses. The Union suffered 5800 casualties. The Confederate figures are not precisely known as to dead and wounded; but over 6000 of them were captured by Union forces. Soon thereafter Grant sent Sherman off to help Burnside against the Confederate army entrenched against him outside Knoxville. Longstreet drew off his Confederate forces in the face of this new Union presence. Knoxville was thus also relieved of further Confederate pressure. The Union army then settled in at Chattanooga for the winter – in preparation for the next spring's offensive against central Georgia, the very heart of the Confederacy. |

Gen. Grant – commander of all Union armies of the West   Union Generals Hooker and Sherman - brought in to help Thomas, now commanding the Army of the Cumberland  Union Gen. Burnside – defends Knoxville against Longstreet |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges