|

| Meanwhile

back East in Virginia, General Hooker had spent the winter months of

early 1863 rebuilding the demoralized Northern Army of the

Potomac. As the spring approached, he felt he was ready to take

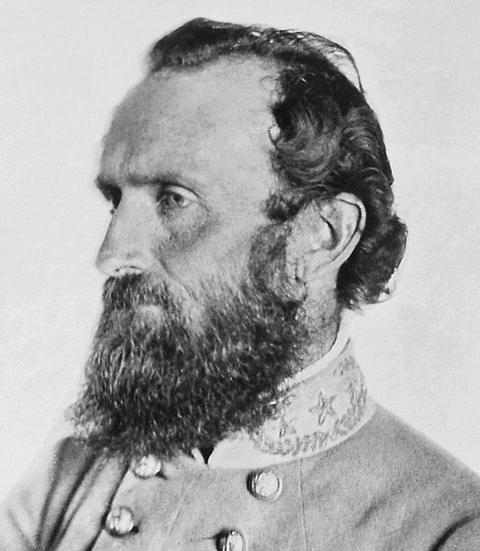

on Lee and the Confederate army still positioned at Fredericksburg. But rather than attacking Fredericksburg head on, Hooker decided to divide his 134,000 man army into three units and swing to the west of Fredericksburg to draw Lee away from the town where he was less protected from this western approach. Hooker hoped to lure the Confederates into a position where he could encircle the smaller Confederate force with his divided army – and crush it in the midst of this gigantic three-pronged pincer. The plan worked – at least to the extent of getting Lee to leave Fredericksburg behind him and come out to meet the Union army. On May 1, Lee and his 61,000 men met a Union over twice its size 10 miles to the West of Fredericksburg at a crossroads clearing known as Chancellorsville, in the midst of a densely wooded region known as the Wilderness. But oddly, Hooker turned cautious at this moment and settled into a defensive position against the Confederates, passing up his opportunity to press them with his superior numbers. Then on May 2 the smaller Confederate army gambled their fortunes by dividing their army into two groups, with Lee holding Hooker's attention to the east so that Jackson could move his troops around behind behind Hooker and trap the larger Union army in a Confederate pincer movement! Hooker disregarded information about Jackson's troop movements, certain that these Confederate troops were merely slipping away from the confrontation! But late in the afternoon, Jackson's 25,000 troops suddenly appeared on the Union's western flank, driving it back east two miles to where the main Union army was positioned. But the Union army was still in a very excellent position, atop high ground (Hazel Grove) which still separated the confederate forces, with Jackson to the west of the Union army and and Lee to the east. Then on the next morning, May 3rd, Hooker oddly enough withdrew from this secure position. The Confederates immediately seized the ground and brought their divided army together. From here they pressed the Union army in bloody battle. The fighting continued two more days – as Union reinforcements intended to relieve Hooker were brought in from Fredericksburg, only to be held off by the Southern army. Finally on May 6 Hooker broke off the engagement and retreated back across the Rappahannock River, humiliated in his inability to defeat an army less than half the size of his. The loss was great on both sides. The Union lost 17,000 soldiers, and the Confederated nearly 13,000 soldiers. With the retreat of the Union troops it certainly amounted to a humiliation for the North. But Chancellorsville had also been a major tragedy for the South. It could not absorb these huge losses in men as the North could. Further, General Jackson had been mortally wounded. It was a tragic accident, for he had been shot by his own men the night after his successful encirclement of the Union forces. He was out studying the lay of the land in preparation for the next day's engagement. Confederate guards had mistaken him for an enemy soldier. On May the 10th he died – an irreplaceable source of Southern bravado. |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges