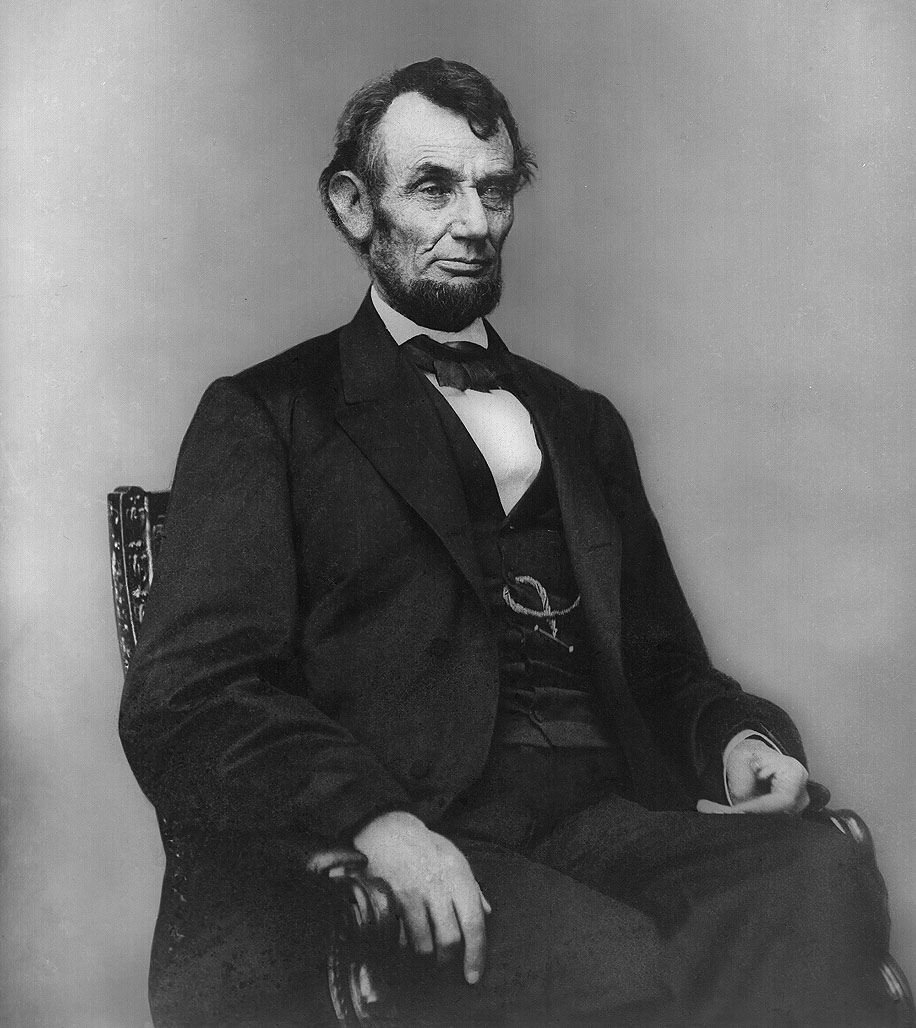

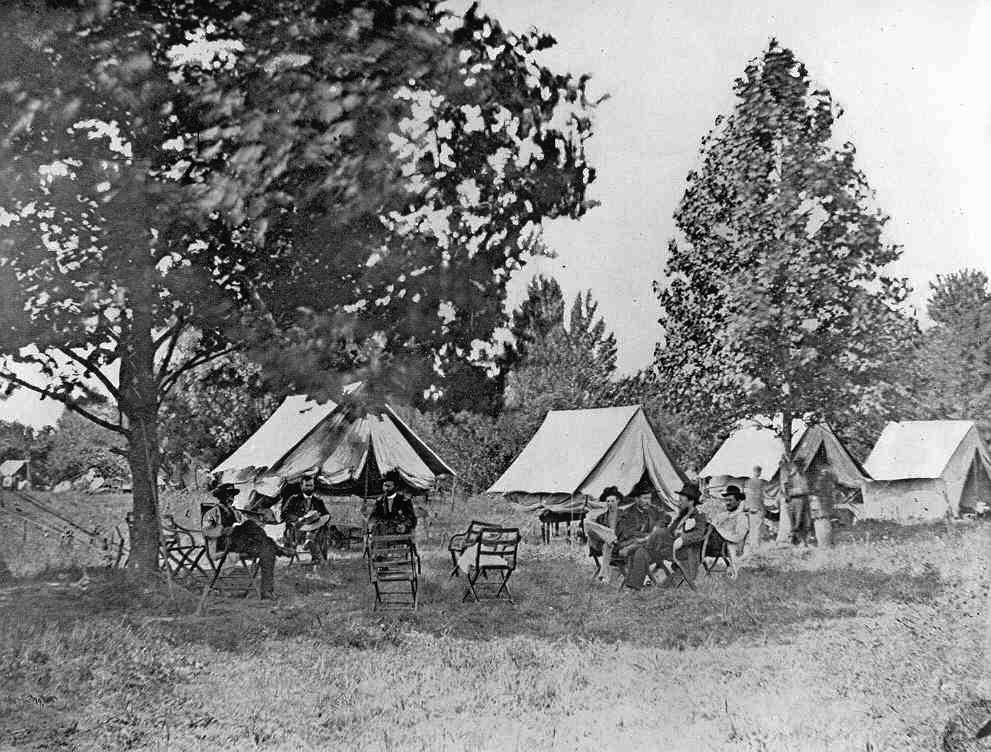

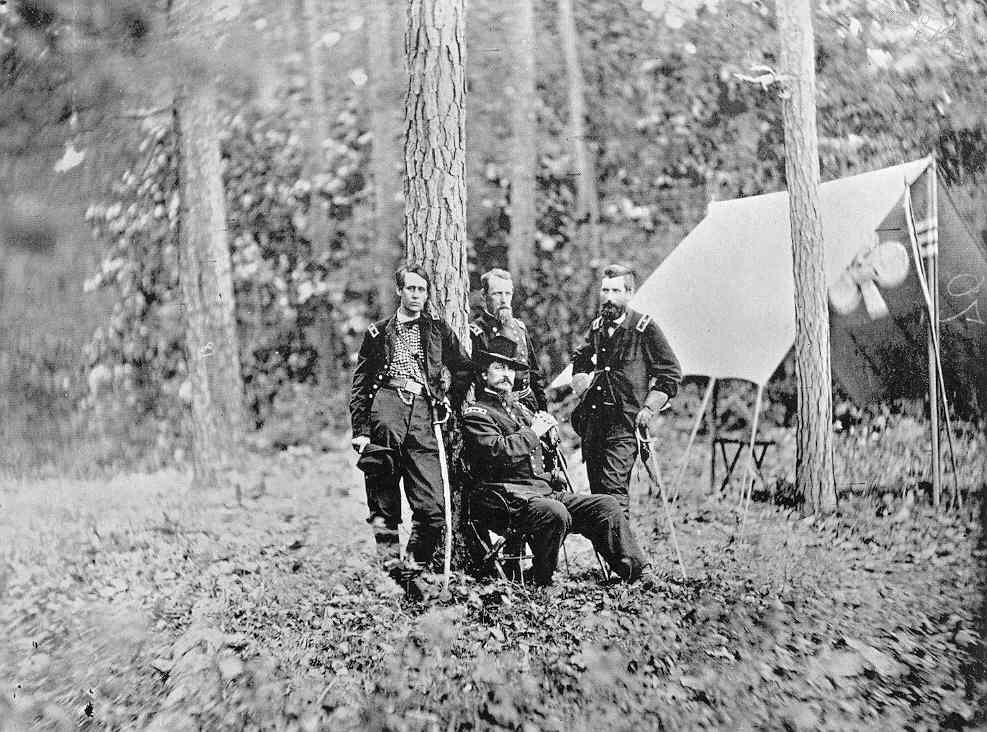

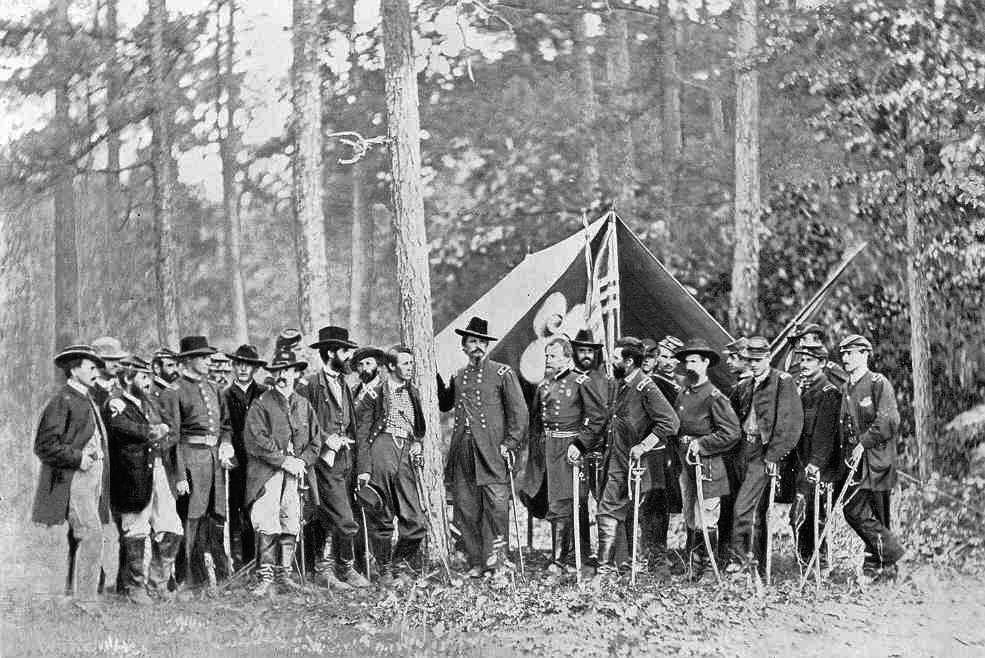

In early 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to

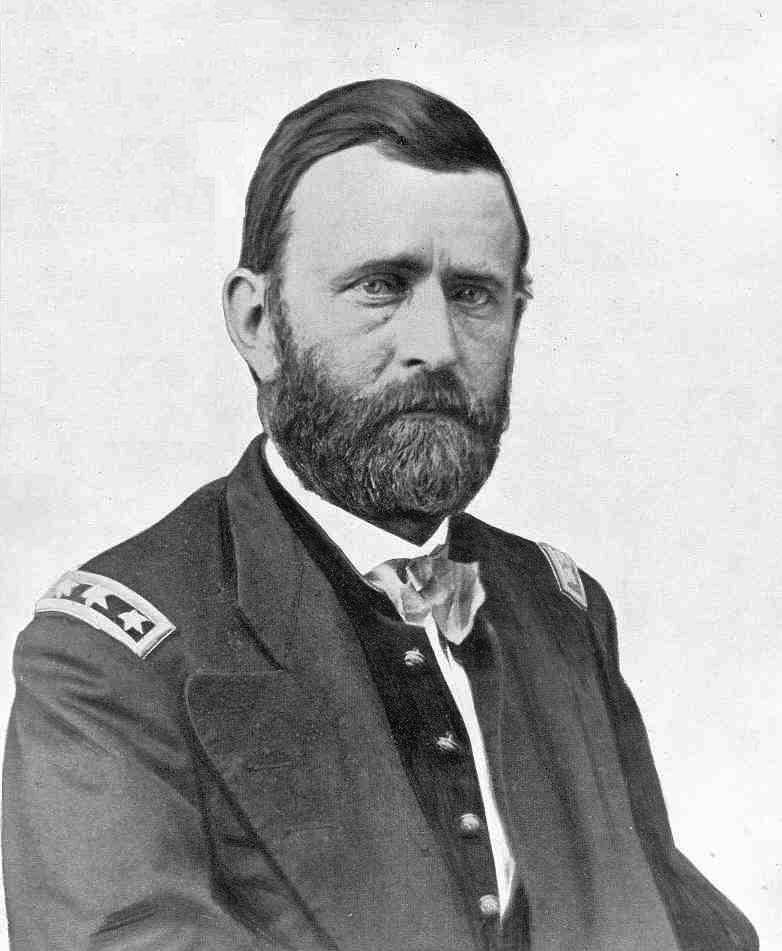

Lieutenant General, giving him command of all the Union armies. Grant

turned his armies (the armies of the Tennessee and Cumberland now

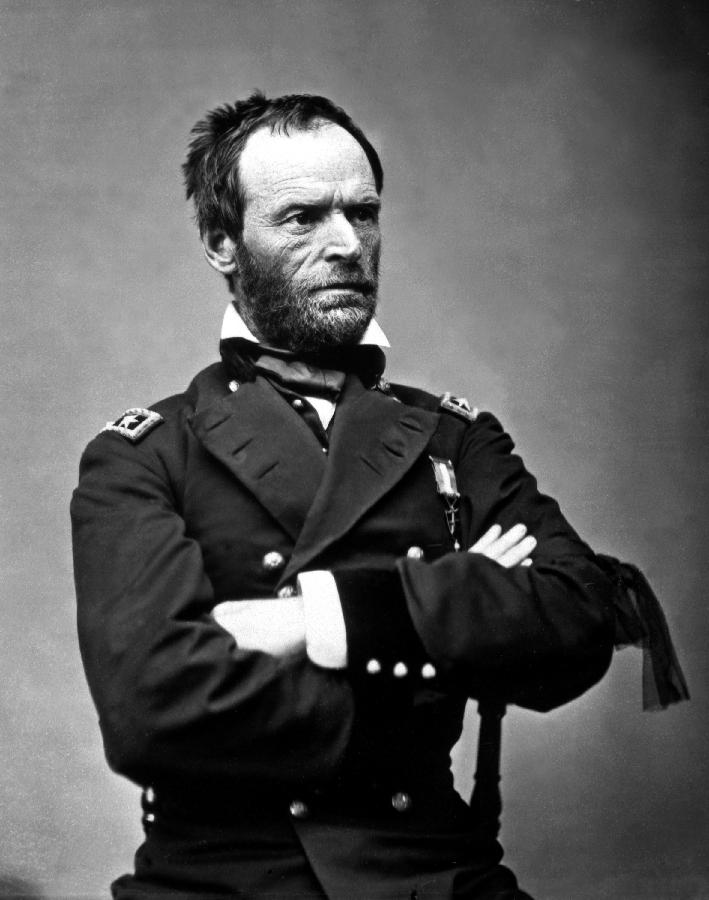

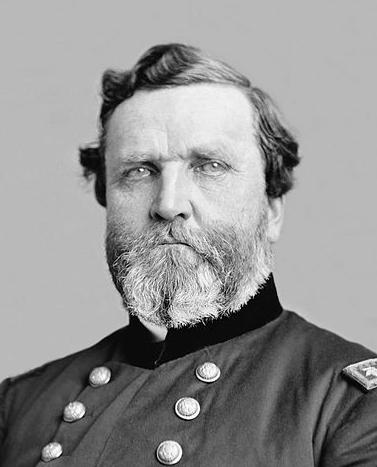

combined) over to General Sherman and headed to Washington to take

command of the entire war effort. His plan was to have Sherman march

south into Georgia from his position at Chattanooga, in order to take

the vital Confederate heartland at Atlanta. At the same time Meade's

Army of the Potomac would attack Lee's Army of Northern Virginia (with

Grant in camp with Meade) from the north and General Benjamin Butler

would attack Richmond coming up from the south along the James River

(similar to McClellan's Peninsula Campaign two years earlier.)

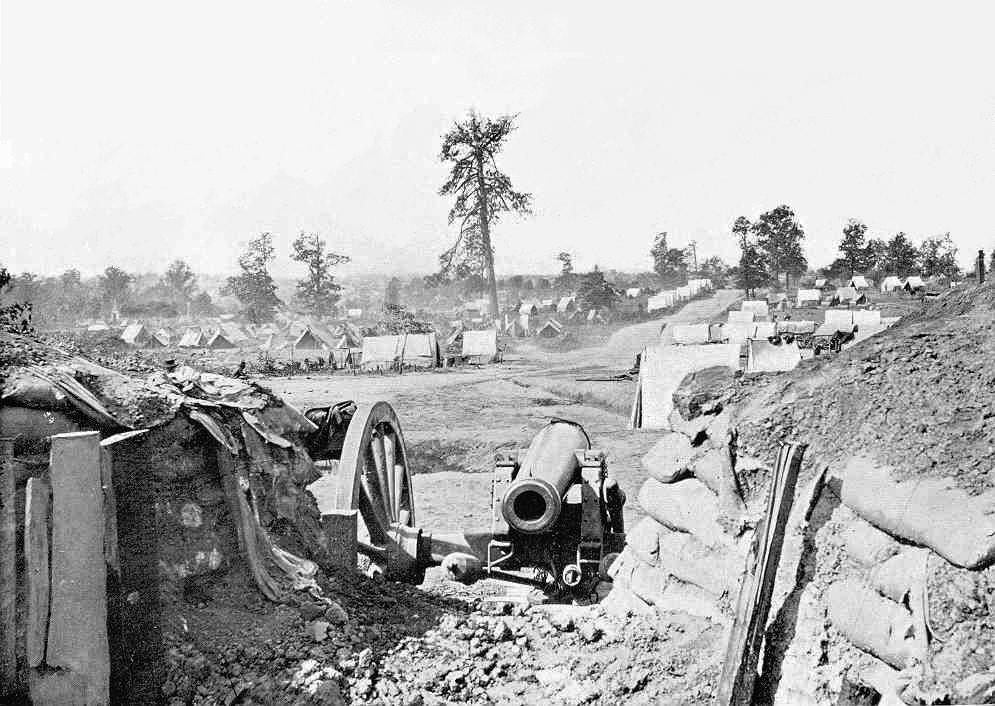

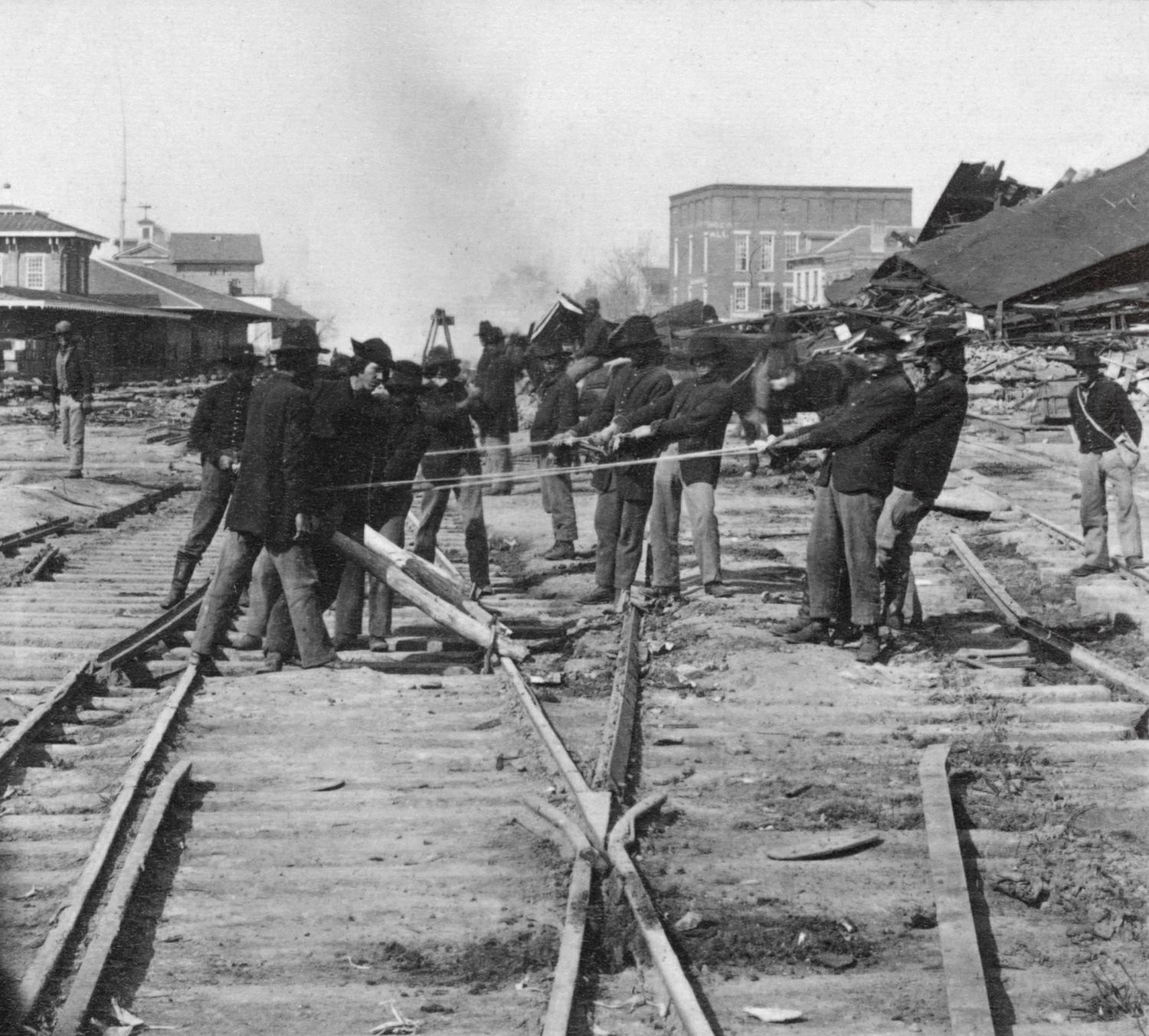

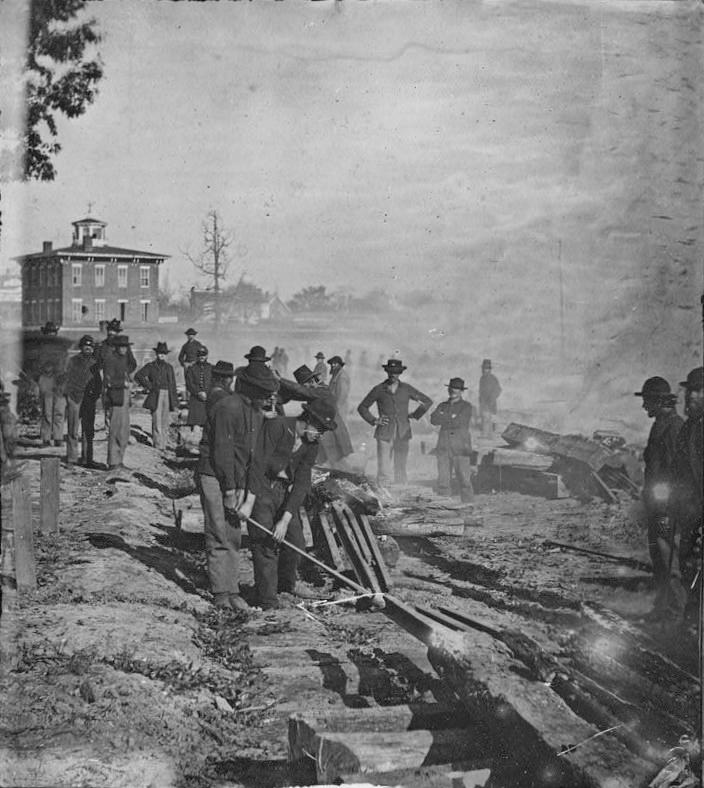

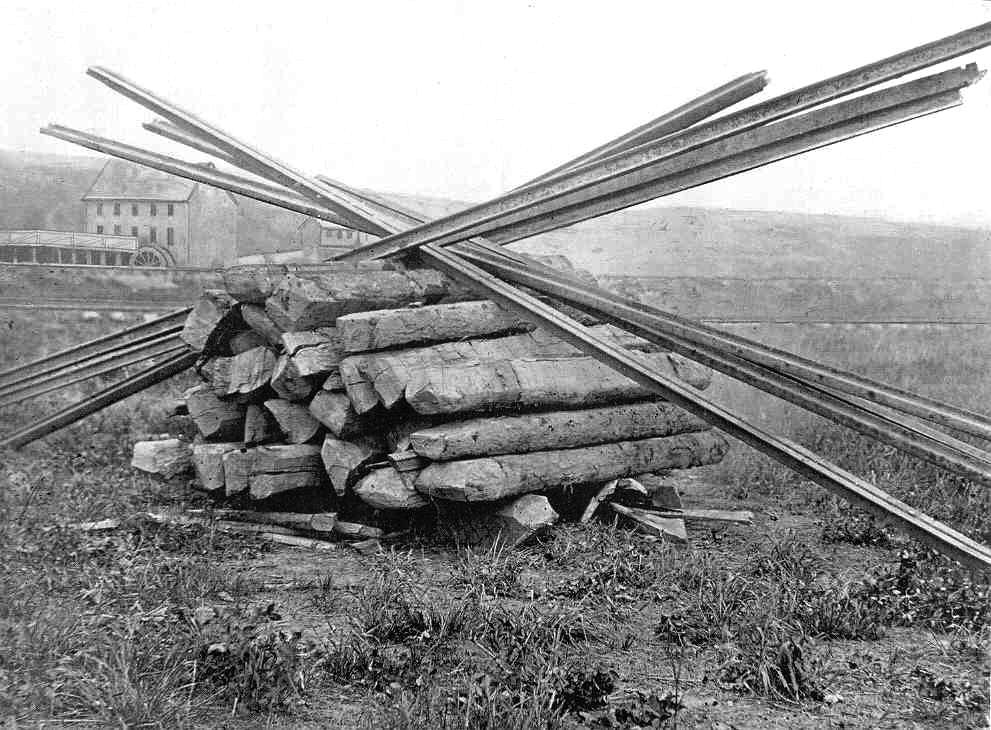

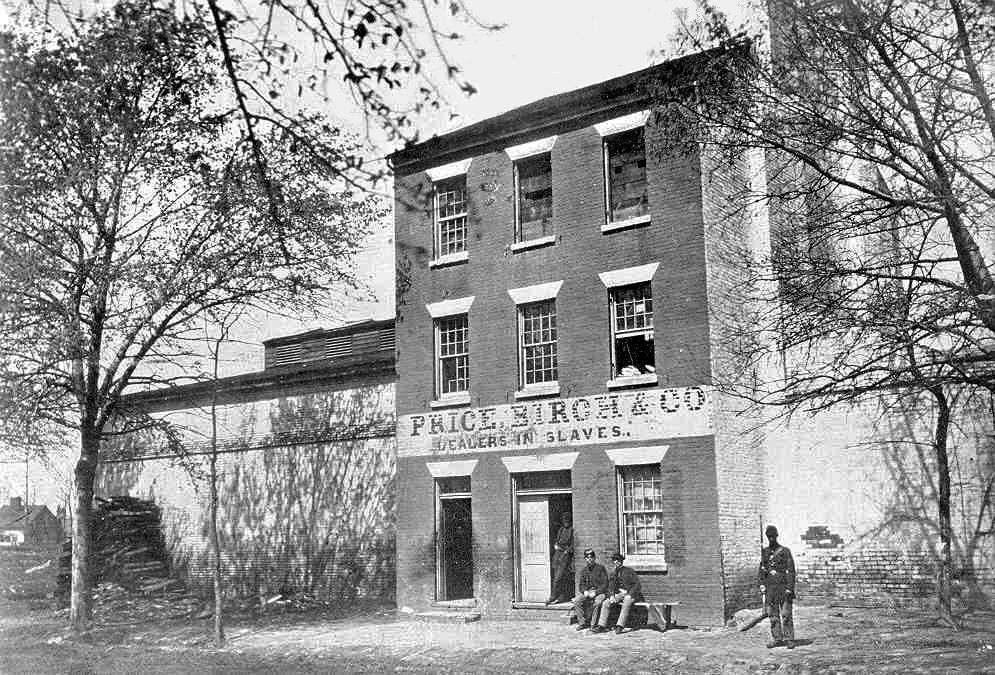

It would be total war, designed to crush

the South's economic and emotional as well as military capacity to wage

war. Under Grant's command the war would be fought very differently,

smaller battles, but one immediately after another, with no letup in

the hits the Union troops were to make on the Confederate troops.

Grant

would continually attempt to swing around Lee's forces, with Lee being forced to give

ground little by little in order not to be flanked or surrounded by

Grant's forces.

Lee now understood that he was in

trouble, with the Union troops unwilling to break off after a battle

but instead hanging onto his troops like bulldogs, wearing the

Confederates down little by little.

The Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7)

The

two sides met near Spotsylvania in a wooded area with dense underbrush,

that came to be termed the "Wilderness." They bloodied each other

severely, with no clear victor and with huge losses registered on both

sides. Grant’s intent to swing eastward around Lee was met by

Longstreet, who managed to hold off Hancock. Likewise an effort

by Longstreet to reverse the action also failed when he himself was

wounded (by his own men). On the third day of the action Grant

broke off the engagement. But by no means was he in any way

dissuaded from his origin plan.

Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21)

The next day Grant and Lee met in battle as Grant again attempted to

swing southeast around Lee ... who had retreated to the

crossroads of the Spotsylvania Court House and had dug in there.

When Grant attacked Lee he found that he could not break the four-mile

long Confederate line. He attacked at one well-defended point in

the line (that came to be known as the "Bloody Angle"), losing huge

numbers of his troops in the effort. After 24 hours of brutal

hand-to-hand fighting, after which he accomplished no gains, he backed

his men off. He did not give up the fight but attempted several

other strategies over the next days none of which yielded him any

advantages. The Confederates attempted a counter assault.

But that too turned out to fail. Finally Grant broke off and

headed his troops southeast in another attempt to swing around behind

Lee.

Cold Harbor (May 31-June 12)

Union cavalry had taken control of the crossroads of Cold Harbor, about 10

miles northeast of Richmond and were soon joined by the bulk of Grant’s

army. The Confederates again dug in, creating a line of defense

about 7 miles long. Union attempts to overrun both the northern

and southern extremities of this line failed horribly.

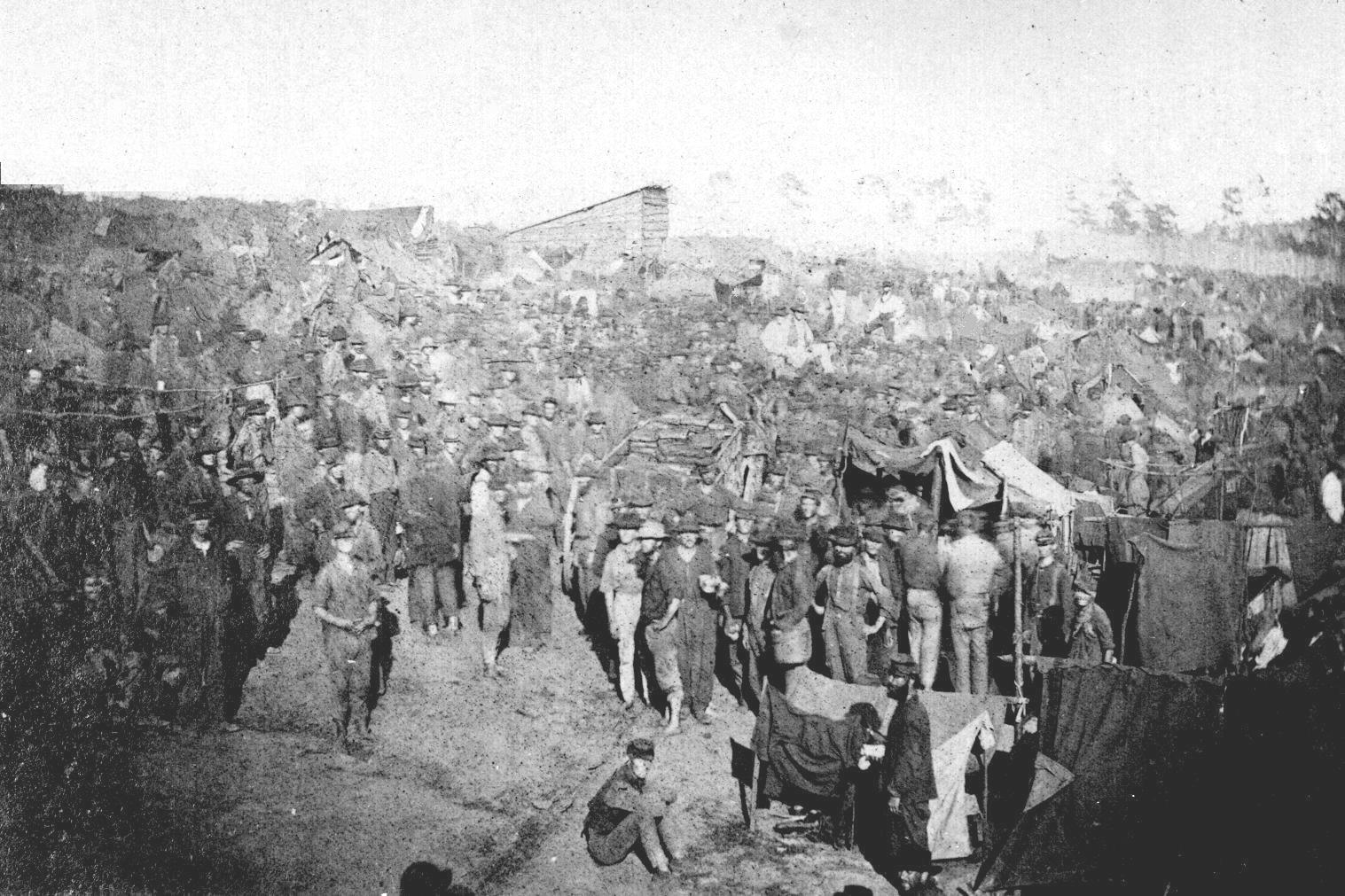

Grant learns some valuable lessons

At the Spotsylvania Court House and Cold

Harbor, Grant learned a lesson that he would not repeat: do not break

off from your adversary long enough to give him a chance to dig in.

Grant's attack on Lee's Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania had proven to be

very costly to Grant, and at Cold Harbor a dug-in Lee proved impossible

to dislodge by direct assault. From this, Grant learned to never again

attempt a direct assault on a well-defended position, as modern arms

give the defenders a tremendous advantage.1

Once again Grant swung his forces east

and south, determined not to give up despite the terrible thrashing his

men had received at both Spotsylvania Court House and Cold Harbor. He

had lost over 52,000 men in the period since he started his Overland

Campaign in early May. But Lee had lost 33,000 men, a much larger loss

proportionately to his total troop size, and thus was much less able to

afford such a high loss.

Meanwhile

Butler’s campaign in the Peninsula had resulted only in his army being

surrounded ... necessitating Grant’s coming to the rescue. But

all the action in Virginia nonetheless tied down Lee in the defense of

Petersburg ... preventing him from coming to the aid of the Confederate

troops trying to hold off Sheridan’s attacks in the Shenandoah Valley

and Sherman’s advance through

Georgia.

Grant

takes over the effort to bring Virginia to defeat

Grant

takes over the effort to bring Virginia to defeat

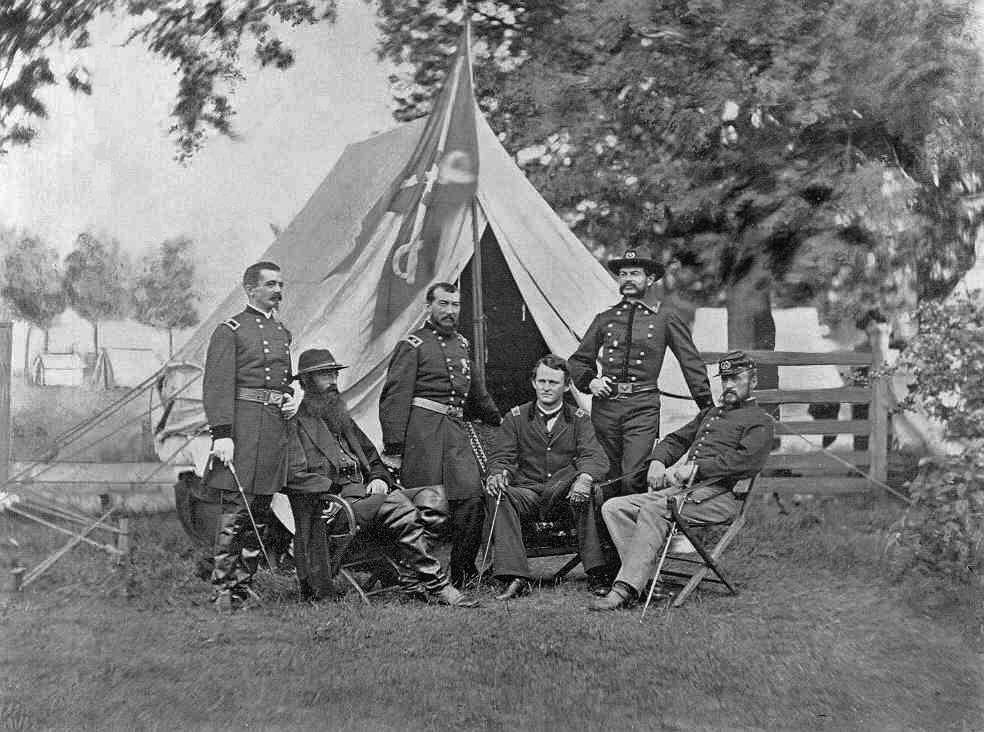

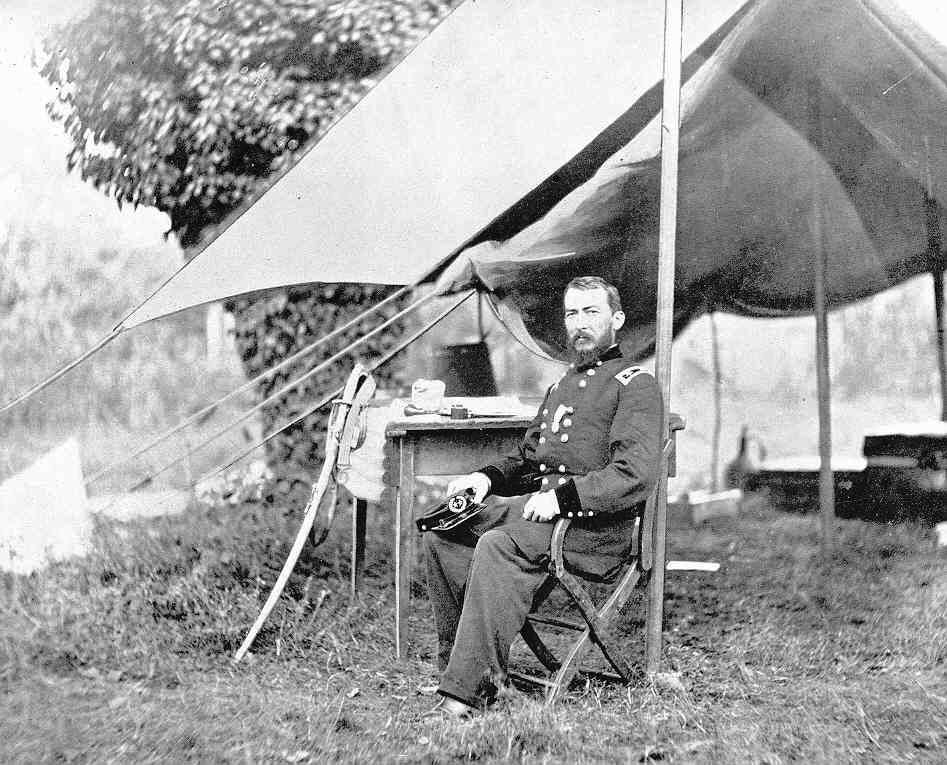

Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign

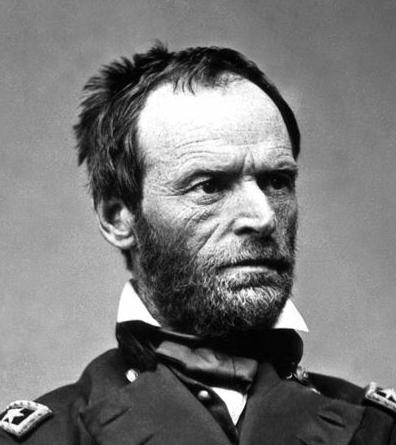

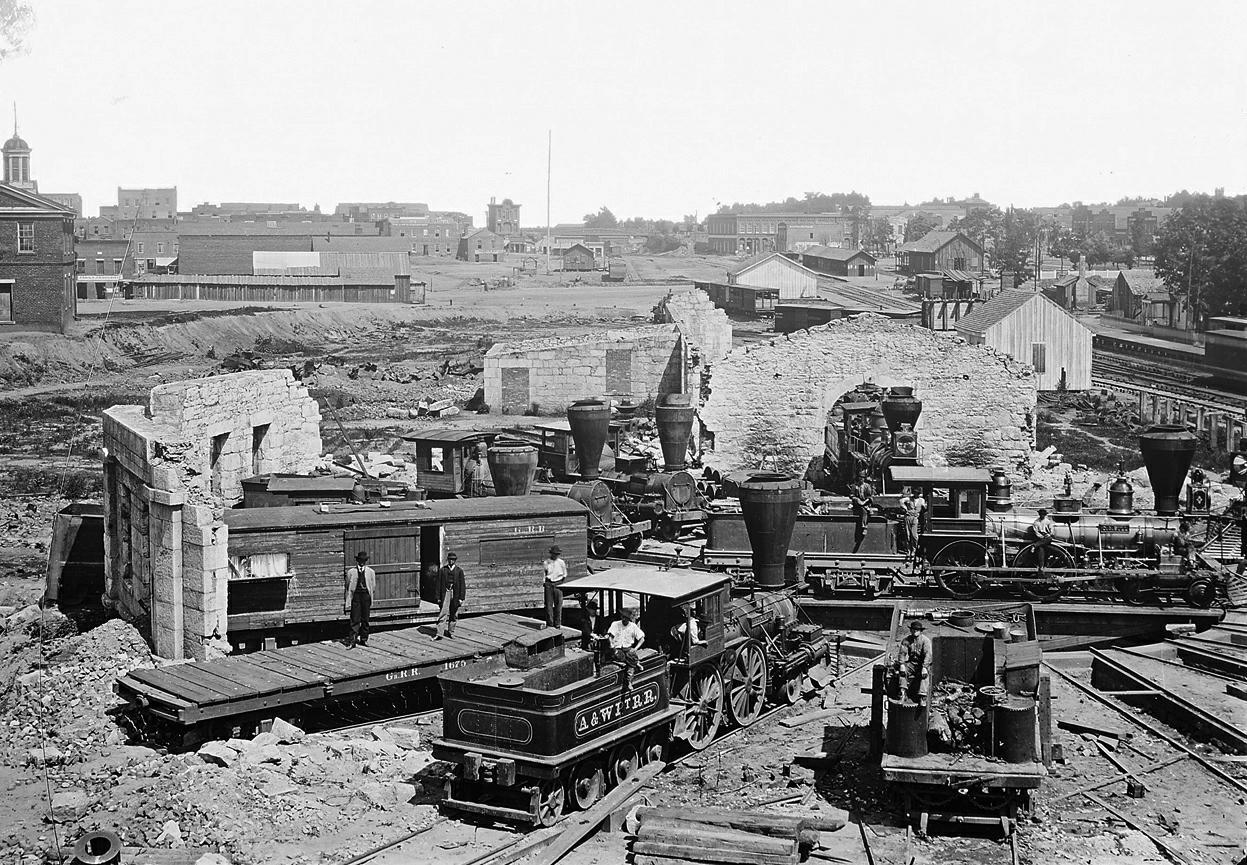

Sherman’s March on Atlanta

Sherman’s March on Atlanta The

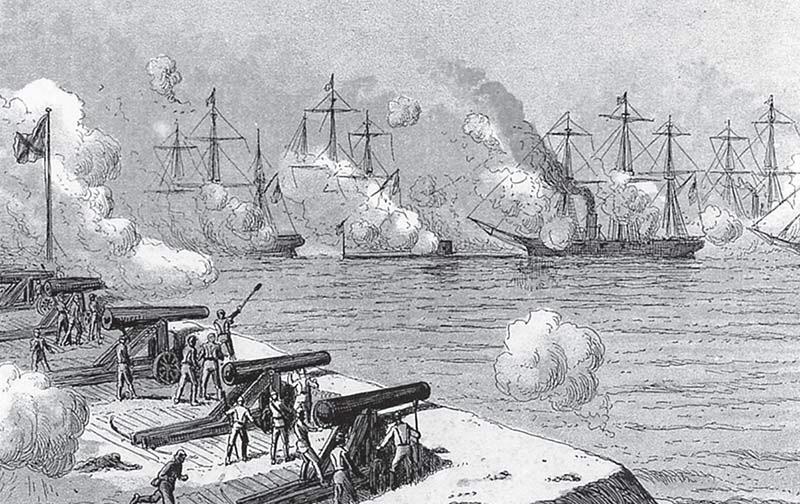

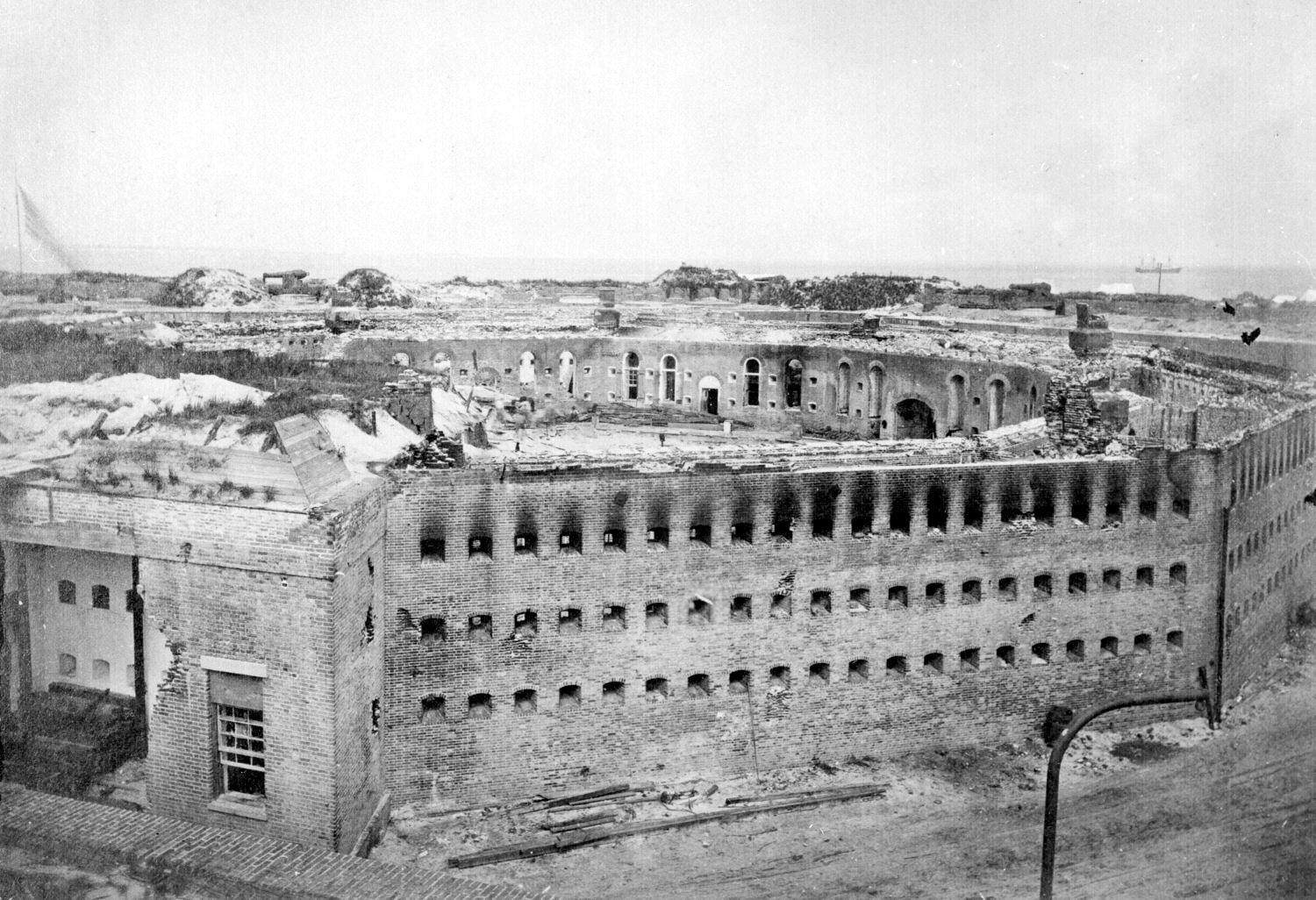

Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5-23)

The

Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5-23)

The

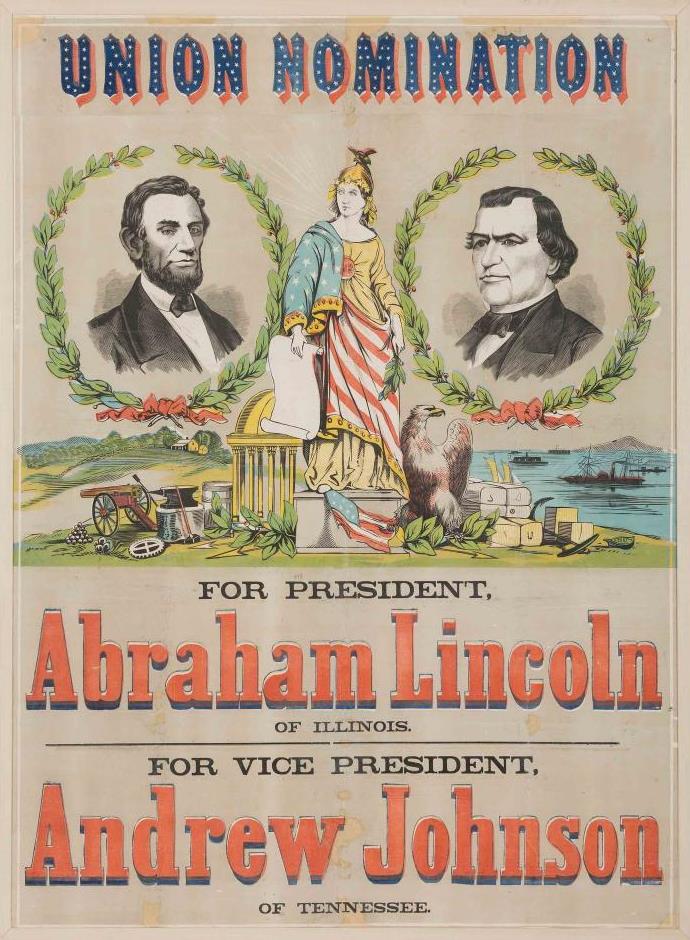

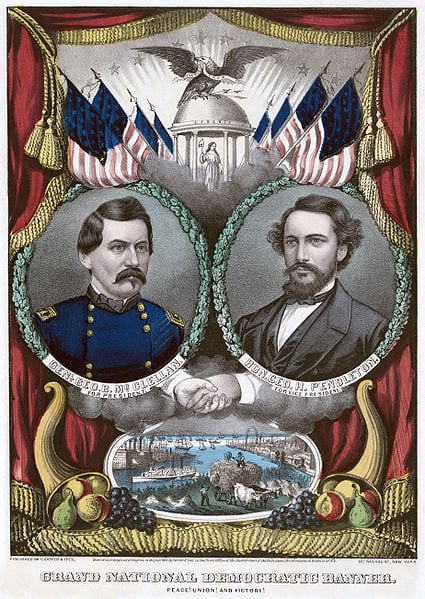

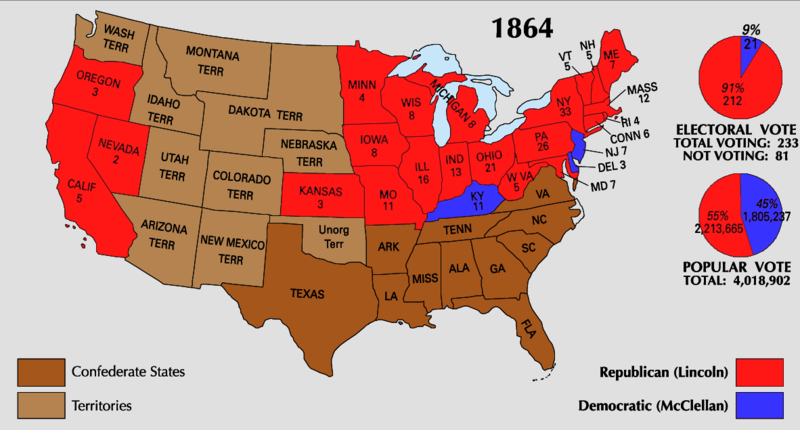

Election of 1864

The

Election of 1864

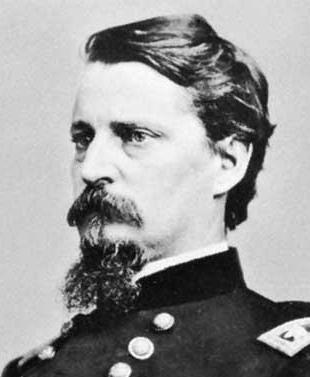

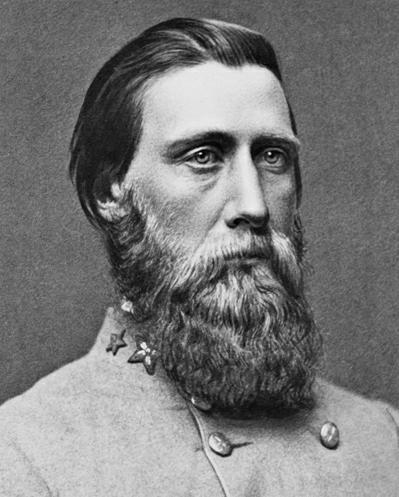

Hood attempts to cut off Sherman’s line of

supply

Hood attempts to cut off Sherman’s line of

supply

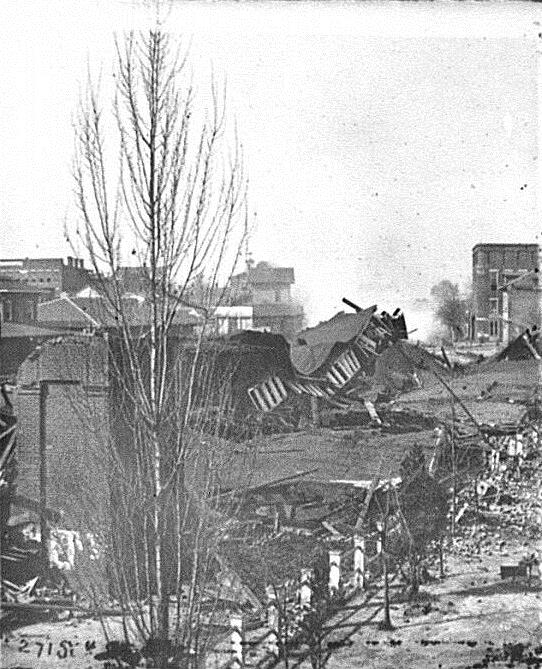

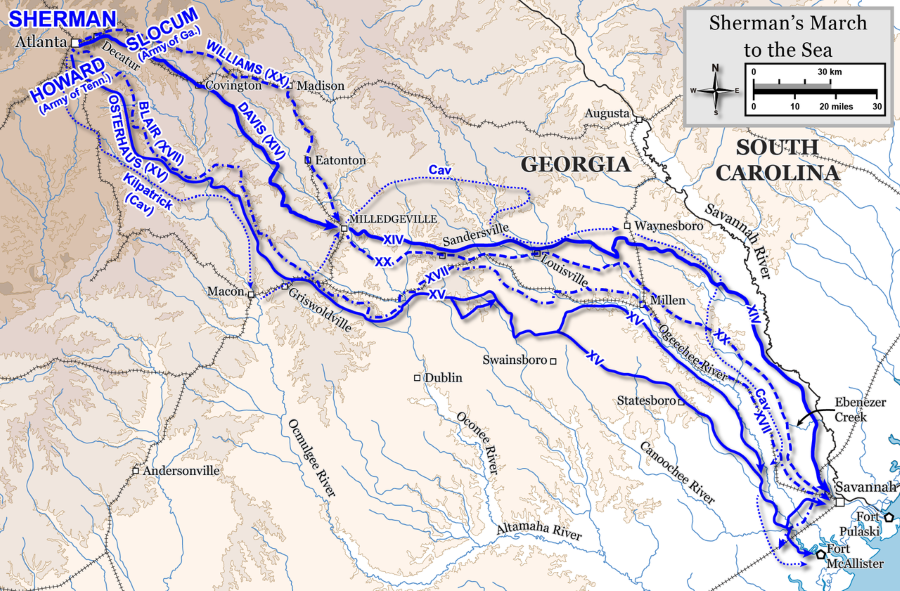

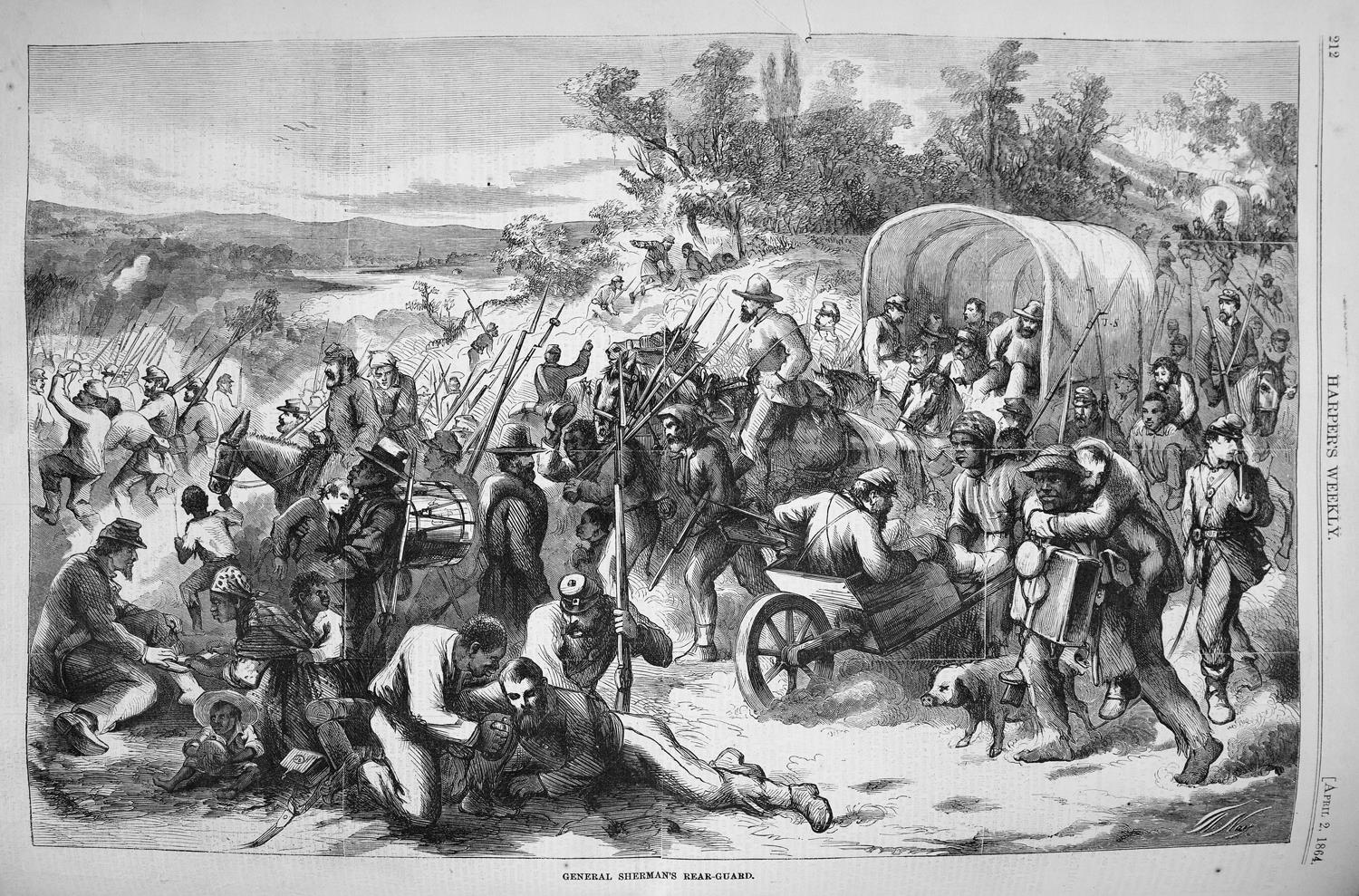

Sherman’s "March to the Sea" (at Savannah -

November-December)

Sherman’s "March to the Sea" (at Savannah -

November-December)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges