|

|

The

1868 national election The

1868 national election

Corruption on a grand scale Corruption on a grand scale

Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall The

1872 national election The

1872 national election The 1873 financial

panic The 1873 financial

panic "The South will rise again" "The South will rise again" Grant

finishes out his term amidst more rumors of massive

scandal Grant

finishes out his term amidst more rumors of massive

scandalThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 323-328. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

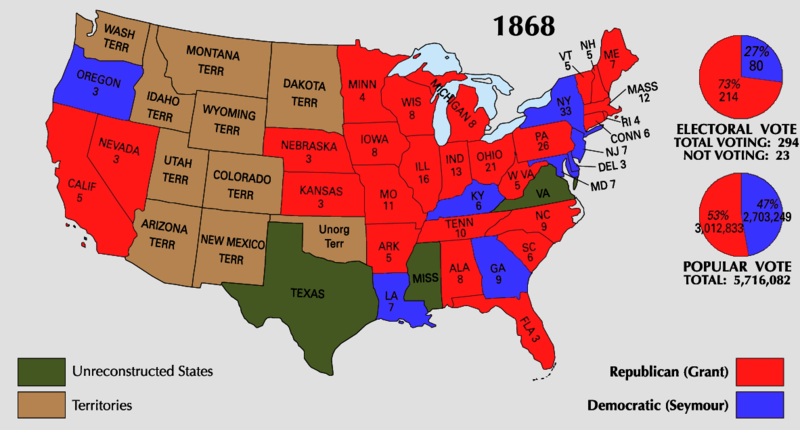

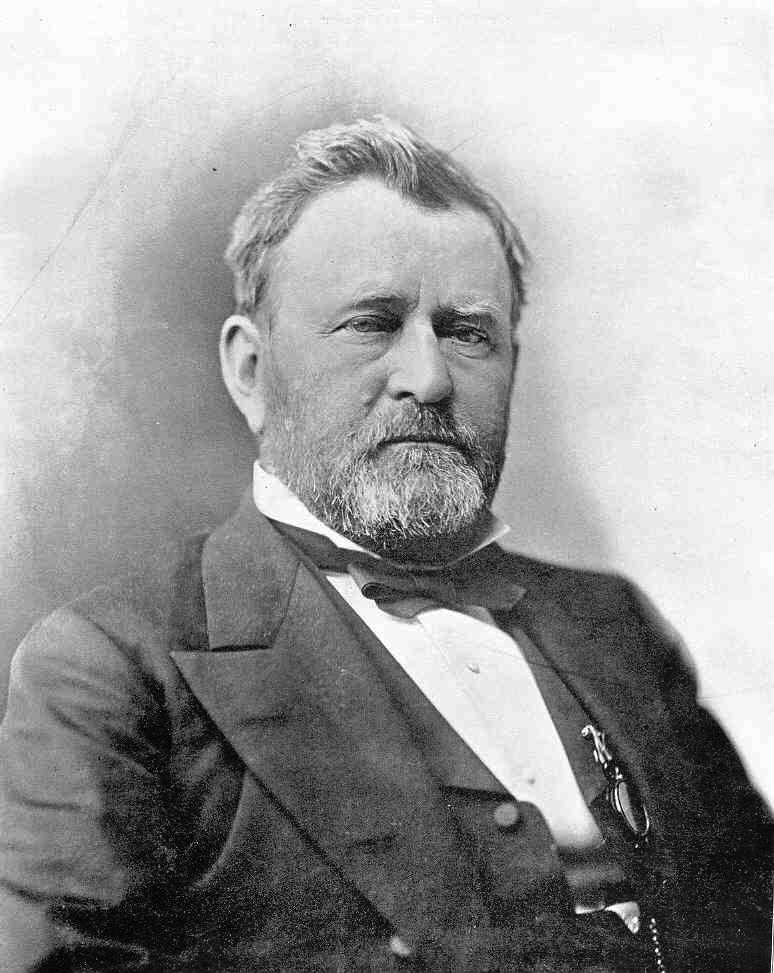

Grant elected president (1868)

The election was so close that Republicans realized that if Confederates disqualified by the Fourteenth Amendment had been able to vote (plus the three unreconstructed Southern states not yet allowed to vote), the election would have gone badly for the Republicans. Sensing that any potential Democrat victory would undo the Republican Party's Reconstruction program, Congress was quick to put into play in 1870 the Fifteenth Amendment, making it illegal for a state to deprive a citizen of the right to vote because of race, color or previous condition of servitude. As a condition for readmission to the Union, the last three hold-out Southern states – Texas, Mississippi and Virginia – had to approve both the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

|

|

|

But Grant as a president was going to be much less aggressive than he had been as a general. Tragically, he tended to trust too much those he had placed in positions of authority and tended to be slow to check out rumors of corruption rampant in his administration, or at least within the higher realm of politics within the America he was supposed to be inspiring and directing. Grant himself was not involved in the corruption and often did act – usually belatedly – when a national scandal broke out. The Fisk–Gould gold scandal A scandal that erupted early during the

Grant Administration was the effort in 1869 by Wall Street tycoons Jim

Fisk and Jay Gould to corner the American gold market. Buying up all

the gold they could at $135 an ounce, thus diminishing the nation's

gold supply and driving up the price of gold to $160 an ounce, they

anticipated gaining a huge windfall profit when they finally unloaded

their gold. But Grant learned of their scheme and stepped in to release

some of the federal government's gold supply, thus bringing down the

price of gold. Fisk and Gould thus came away with a much smaller profit

than they had anticipated. Sadly, although Grant's action was quite

correct, he could not escape the tendency of people to blame the

president for allowing this to happen in the first place.

The Crédit Mobilier scandal

An even bigger scandal broke out when the public got wind in 1872 of the widespread corruption involved in the huge project of laying railroad track designed to connect the nation East and West. As early as 1862, during the Civil War, the federal government had authorized $100 million in capital to build a 1750-mile railroad westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa (on the strategic Missouri River) by the Union Pacific Railroad Company and eastward from the Pacific Ocean at San Francisco by the Central Pacific Railroad Company – through desert, mountains and unfriendly Indian territory. It was undertaken as a matter of national interest rather than as a money-making capitalist enterprise because it was not expected that the venture could ever recover its costs simply through the revenues it would acquire when it was actually up and running. It simply had to be built, by public funding if necessary.

Of a very highly questionable nature1 was that the directors of both the Union Pacific and the Crédit Mobilier happened to be the one and the same individuals. Worse, Union Pacific stocks were sold to its directors and also to a number of United States congressmen whose vital votes supported this expensive venture (some thirty representatives from both parties were involved). Stocks were sold to these insiders at par value, well under their market value, thus securing enormous profits for these privileged investors (some estimates put their profits at around $20 million total) when they turned around to sell their shares on the open market. Further, the railroads were granted $16,000 for each mile of track laid on flat land, $32,000 for hilly terrain, and $48,000 for mountainous terrain, tempting the companies to wander across as much terrain as possible and also to exaggerate their claims of miles of track laid, a monumental piece of corruption which finally in 1872 the New York City newspaper Sun uncovered and ran a damaging exposé about, just in time for the 1872 national elections. Once the revelation of the scandal broke in 1872, Union Pacific stock dropped in such value that it left other stockholders nearly bankrupt. And once again Grant was blamed by an outraged media for not having intervened to block this whole corrupt venture. But it was a sign of the times. Such scandals, especially related to the hugely lucrative business of railroad construction (which was expanding rapidly everywhere in the country), would unfortunately be very typical of the way America found itself developing economically in the last quarter of the 19th century. 1There

was considerable opposition within the general public and in Washington

to the venture by those who did not see the strategic need for such an

expensive venture.

|

|

|

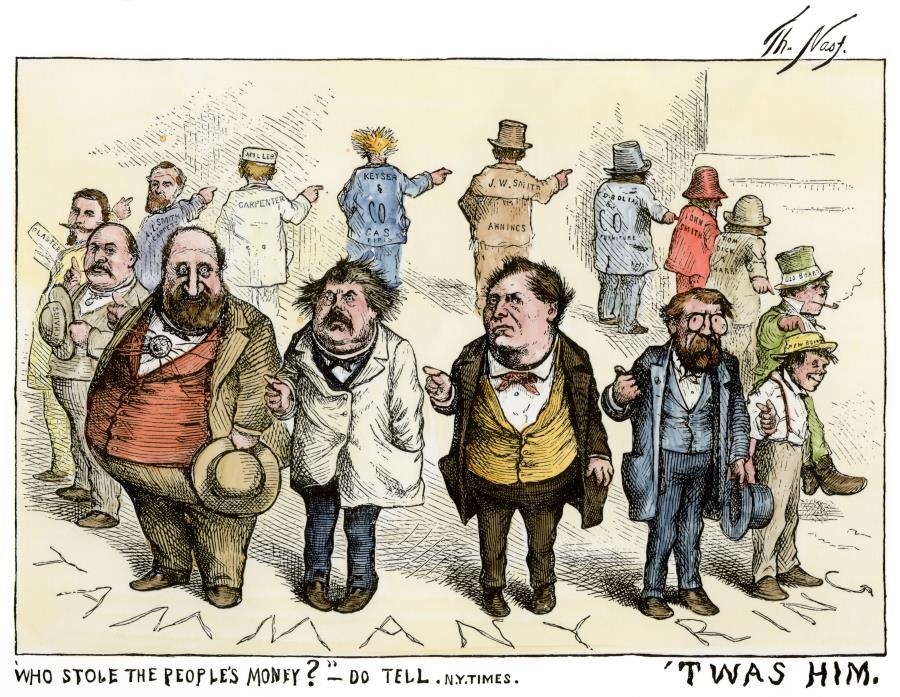

He was reported to have helped Jay Gould and Jim Fisk take control (1866–1868) of the Erie Railroad from the equally adventuresome Cornelius Vanderbilt with fake stock (which Boss Tweed was able to get the New York state legislature to authorize), receiving a considerable share of that stock himself plus a position on the company's Board of Directors. The amount of graft that Boss Tweed acquired is still uncertain, it was so extensive. He was accused and tried in a series of court cases starting in 1873 for stealing from the New York taxpayers an amount ranging from $25 to $45 million (more recent estimates put that figure at closer to 100 million in 1877 dollars). He was in and out of prison (at one point he even escaped to Spain) until 1878, when he died in prison at age fifty-five. But Tammany Hall itself quietly survived Boss Tweed's demise, to conduct business as usual well into the 20th century.

|

|

|

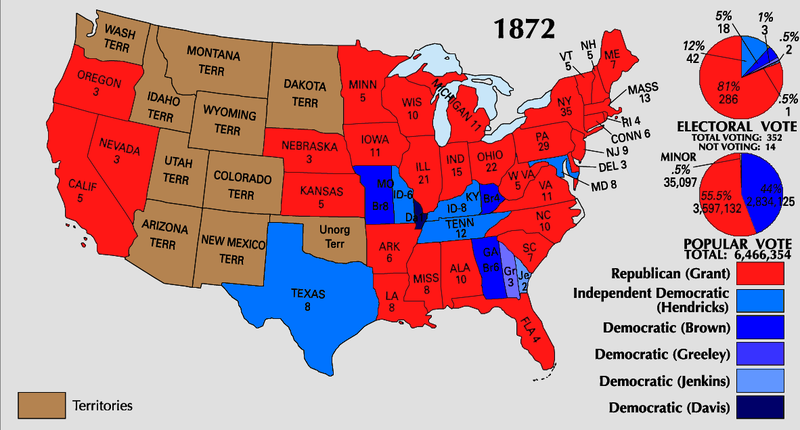

All this corruption, well-covered by press exposés, naturally called forth the need for extensive political reform in the North itself. Consequently, a new political grouping came into being in advance of the national elections: the Liberals. Taking a broader view of the South than the vengeful Radicals, the Liberals found themselves joined with the Democrats (ironic for such a reformist grouping, since the Democrats were identified closely with Tammany Hall) in calling for a lifting of the heavy-handed Reconstruction program imposed on the South by the North. In anticipation of the 1872 presidential election they nominated newspaper editor and ardent reformer (also Socialist) Horace Greeley, to run against the Republican Party's candidate, President Grant. In the election itself Grant won handily the vote of the electoral college (300 to 60), though Greeley won 44 percent of the popular vote. Thus Grant was going to have four more years in the White House. But Grant's second term in office would be as troubled as his first term.

|

|

|

The failure of a major brokerage firm, brought down by its heavy involvement in Northern Pacific railroad bonds, set off a financial panic on Wall Street which soon led to the collapse of a number of banks and other investments houses. The situation became so bad that Wall Street shut down business for ten days to cool down the panic. Worse, this crisis was timed with the decision by Grant to remove readily available silver as a standard for the dollar, leaving the dollar reliant only on gold as its metallic standard. While this may have strengthened the dollar, it restricted dramatically the ability of investors and entrepreneurs to gain easy credit for opening up or expanding their business base. This hit particularly hard the massive farming industry which always relied on bank loans to carry farmers from planting time in the spring until harvest time in the fall, when finally the farmers would see income. Grant did not understand the severity of the financial crisis that hit the country in 1873, thinking the downturn in the nation's economic activity to be merely a normal fluctuation in the economy – which certainly happens from time to time. But this was no mere fluctuation, the economy going into a stall which lasted five long years (termed at the time the Long Depression) and which saw almost ninety railroad companies go bankrupt. Grant refused to back down from his tight monetarist strategy, believing that the strong dollar was more important to the nation's economy than the easy-credit strategy that the nation had been pursuing, a strategy leading to the vast corruption that had sullied the reputations of the railroad and banking companies. But this was a bad time to put additional brakes on the nation's economy, because it would have severe political as well as economic consequences. As a result of the 1873 Panic, there occurred a major sweep in 1874 of the Republicans out of office everywhere, including the U.S. House of Representatives, where the Democratic Party took control. This did not bode well for a continuation of the North's Reconstruction program for the South.

|

|

|

In the meantime political tensions had been building in the South, where the Democratic Party was regaining political ground under the leadership of former Confederate officials, termed Bourbon or Redeemer Democrats. They had been gathering Southern White political support by stoking the Whites' fears of the rising political power that the Blacks had acquired through Congress's Reconstruction policies. Also the KKK was gathering strength – and vindictiveness. This in turn brought Congress to pass another round of legislation (1871–1872) designed to protect Black voting rights in the South and curb the behavior of the KKK and other Southern organizations like it. But this only inspired even greater bullying behavior on the part of those White racist organizations, making life even more difficult for the Southern Black. One by one these Redeemer Democrats were able to take over the state legislatures of the South and begin the passing of a round of segregationist "Jim Crow" laws. But in addition to playing the race card as their ticket to power, they employed other populist tactics such as calling for the end of the huge indebtedness of their state governments – by simply repudiating those debts – and by calling for the end of government subsidies for businesses (such as the railroads). It made for great popularity among frustrated White voters, but foolishly undercut the possibility of the South working its way out of its poverty (repudiating debts was a sure way of cutting off any future investments in the Southern economy). And prolonged economic hard times would only harden the attitudes of a racist South.

|

|

|

Grant's tendency to grant unreserved trust to those he had appointed to office would shake his administration to the core. Worse, he would tend to side with those accused of corruption, seeing them simply as victims of political opportunists. Indeed, he seemed totally blind to the corruption going on around him, which was rampant. Payoffs for appointments by officials below him, such as Grant's personal secretary, Orville E. Babcock, were normal procedure during the Grant years. Within his Treasury Department a tax collector had set up a scheme to overlook owed taxes, until a sufficient amount had accumulated that he could then go in and collect, plus a sizable fine which went into the tax collector's pocket. Meanwhile a huge Whiskey Ring owing enormous amounts of taxes ($3 million) on their whiskey had been allowed to develop, until finally Grant appointed an honest treasury secretary who went in and cleaned house. But when Babcock was also implicated in the deal, Grant threw his protection around his personal secretary, and even pardoned a number of leaders of the Whiskey Ring who had been found guilty and imprisoned. Corruption touched everything from the War Department to the Department of the Interior as Grant appointees used their power to extract bribes and other payoffs for their services, becoming simply part of business as usual when dealing with the federal government. Grant did appoint reformers empowered to clean out such corruption. But the corruption was so extensive that his efforts brought little relief from his growing reputation as running a very corrupt Administration. As a consequence, in 1876 the Republican Party distanced itself from him at the convention called to select a new Republican candidate for the presidency.

|

Library of

Congress

Miles H. Hodges