|

|

Capitalism in the "Gilded Age" Capitalism in the "Gilded Age"

The Captains of Industry

(or ‘Robber Barons’ as others termed them) The Captains of Industry

(or ‘Robber Barons’ as others termed them)

The

extravagance of this wealthy elite The

extravagance of this wealthy elite The

American "Middle Class" is doing pretty well for itself as well The

American "Middle Class" is doing pretty well for itself as well

Americans

can afford even the luxury of idealizing the American

woman Americans

can afford even the luxury of idealizing the American

woman Of course not all was

perfect in the picture of American "Middle Class" life Of course not all was

perfect in the picture of American "Middle Class" life

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

During the time of post-Civil-War recovery, a new social dynamic had been rising within the fast-growing American cities: the adoration of modern technology and those who provided it, the promise of wealth flowing out of this dynamic, and the seeming control over life provided by the scientific mentality that undergirded this whole social-cultural revolution. This was due in no small part to the Civil War and its lasting effect on the American economy. The war's demand for steel, and the iron ore and coal to make it, and the railroads and boats to ship it, and the financial institutions to fund its initial outlay, and the laborers to work the whole system – all this had made a deep impact on what was formerly almost purely an agrarian society. Apart from the early railroad ventures during and immediately after the war, the government played in the post-war period only a minimal role in the on-going development of this new industrial society, especially as the war and its needs receded from view and the system seemed to run simply under its own dynamics rather than on the basis of popular social-political demands. Nor was God invited to play a role in the development of this new society. America's Grand Destiny now seemed to be driven forward largely by the huge material rewards that fell to the particularly ambitious and fearless. Fortunes could be made rather quickly by very enterprising individuals (and they could be lost almost as quickly). And these fortunes were awesome, often exceeding (sometimes vastly) the levels of wealth of the European nobility. Indeed, it was a Gilded Age (Age of Gold) for successful American industrialists. This was a perfect setting for the spirit of Darwinism to soar. Certainly the basic theme of this rising social order was quite Darwinian: progress through survival of the fittest. To the strong belonged the spoils of their conquests. But for those who fell to the wayside in this struggle for survival there would be no tears wept. But the risk of this competitive struggle seemed worth it, at least to those who anticipated striking it rich in this new game of potentially limitless opportunity (if you were willing to play it hard and fast). For others, however, this game offered virtually no opportunity – only drudgery and painful hardship on this path of survival. With the closing of the Western frontier and loss of the ability to secure cheap Indian land, farm boys were forced to find work in these industrial enterprises, not with the hope of striking it rich, for there was almost no entry point for them into a game that required substantial startup money or capital to get up and running in this new capitalist system. These farm boys came penniless, offering only their labor. But for their labor they received very little in return. In the eyes of the Darwinists these new industrial workers were not seen as people, as fellow Americans to whom they owed some sense of mutual responsibility. Instead they were viewed by the rising class of wealthy capitalists only as economic costs, costs which they had to keep low in order to gain the profits that would win them victory in this Darwinian game. What was happening to America? Had it gone from African slavery only to replace it with a shockingly similar wage-slavery? Was this the social outcome that so many young men had given their lives for in the recent Civil War? |

|

|

The Captains of Industry (or "Robber Barons" as others termed them)

The rapidly widening gap between hard-working American laborers and the Captains of Industry was vast … and shocking. According to a survey done in 1896,2 of a total of 12½ million American families in 1890, 125,000 very wealthy families, or 1 percent of the total number of families in America, earned over 50 percent of America's total family wealth. The well-to-do, comprising about 11 percent of the total number of families, earned about 35 percent of the nation's family wealth, the middle classes, comprising about 44 percent of the total, earned about 12½ of the total wealth, and the poorer classes, comprising another 44 percent of the families, earned only about 1 percent of the total wealth. And among this very wealthy 1 percent of

the population, an even smaller number of families stood out way above

the rest. A few are mentioned here just to point out how capitalism was

working in the latter part of the 1800s. Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt.

But by the end of the 1830s, Vanderbilt had secured a number of his own steamboat monopolies, and in the early 1840s he began to manage small railroads that connected with his steamboat lines. In 1847 he took over a major railroad running from New York to Boston, and bought out a number of competitors, putting his railroad line in a dominant position on that vital route. Then with the beginning of the California gold rush in 1849 he switched to shipping on the high seas, even at one time attempting to put together a group to build a canal across Nicaragua between the Atlantic and Pacific. He failed at this attempt, but did set up a land and water connection between the two oceans, and then developed a Pacific steam line to California. In the 1850s he bought a large company that manufactured the steam engines for the steamboat industry, and also jumped into the trans-Atlantic steamship business. Even at one point he found himself deeply involved in Central America against a major competitor – and various authorities supporting that competitor ... including some military action. So Vanderbilt moved his operations further south to Panama and then acquired a monopoly on a steamship line running from there to California. During the Civil War he donated and staffed at his own expense his flagship, the Vanderbilt, which was used to hunt Confederate raiders (such as Confederate Admiral Semmes and his warship, Alabama). After the war he was joined by his son Billy in acquiring a number of New York railroads, and brought them together as the future New York Central Line, one of the first corporate giants in America. He also constructed a large railroad terminal in Manhattan on 42nd Street, also the forerunner of New York's Grand Central Terminal, the world's largest train station. The

only time Vanderbilt found his move blocked was in his attempt to buy

up the Erie Railroad, which Jay Gould and his associate James Fisk

fought off by watering down stock (quite in violation of the law, which

Fisk avoided by bribing New York legislators!), to weaken Vanderbilt's

position after Vanderbilt had bought up, at some considerable expense,

what he thought

would be a controlling share of the business. This massive issue of new

stocks by Gould and Fisk devalued Vanderbilt's stocks so badly that his

losses were enormous. This created a deep and lasting enmity between

Vanderbilt and these two equally ambitious and notoriously clever

financial wizards. But Vanderbilt would not again be on the losing side

of this rivalry, a rivalry that lasted all the way up to his death in

1877. At his death he was worth the monumental sum of $100 million,3 most of which went to his son Billy (although he was very generous to his other many sons and daughters). He also donated the $1 million that founded the university in Nashville, Tennessee, that still carries his name, which at the time was the largest charity contribution ever offered by a single donor. He also gave rather generously to churches, including the 8½ acres which he gave to the Moravian Church on Staten Island for a cemetery, where he himself is buried. Andrew Carnegie

2Charles B. Spahr, An Essay on the Present Distribution of Wealth in the United States, New York: T.Y. Crowell & Co.,1896, p. 69. 3This

would make him the second richest man in American history, ranking only

behind Rockefeller. The $100 million would be approximately equivalent

to $150 billion in today's dollars. Interestingly, he lived modestly.

All the lavish Vanderbilt estates that were built across the American

East were actually commissioned later by his descendants.

|

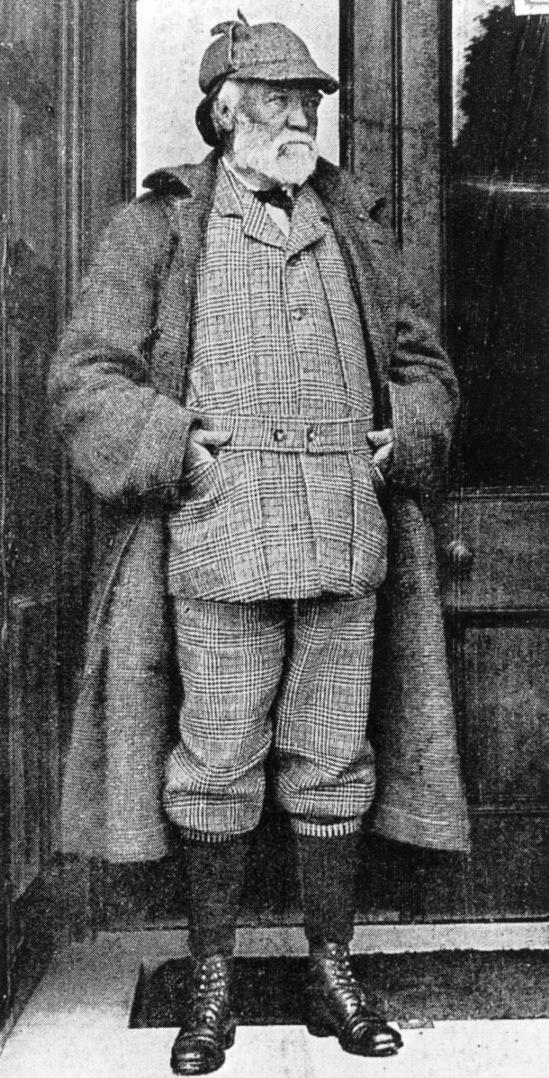

Andrew Carnegie in his Scottish attire

|

Over the years he demonstrated his skill at buying up struggling companies at bargain rates and then reorganizing them into profitable operations. He even at one point came to the aid of the U.S. Treasury in the midst of the Panic of 1893, when by 1895 the Federal Treasury was nearly out of gold and facing financial default. Morgan joined with the Rothschild bankers of Paris to offer to sell the government 3.5 million ounces of gold in exchange for thirty-year bonds. At first U.S. President Cleveland turned down the offer, but then realizing how close the government was to default, finally accepted Morgan's offer. It indeed saved the status of the U.S. Treasury, but undercut Cleveland's standing with the agrarian wing of his Democratic Party. Again in 1907 Morgan stepped in to rescue the American economy, this time caused by a massive sell-off on Wall Street after the failure of a large copper venture threatened to pull down a number of banks that had invested heavily in the venture (actually Knickerbocker, New York's third largest trust company, did fail). This crisis was so big that Morgan did not attempt to answer the challenge alone, but gathered a number of other New York banks to join him in putting money back into Wall Street and restoring investors' confidence, thus averting a stock market collapse. Another crisis soon followed, this time caused by the collapse of a major industrial conglomerate invested in coal, iron, and railroads. With President Teddy Roosevelt's permission, Morgan stepped in to take over the fallen conglomerate, aware that this would invite charges of monopolistic behavior. But it had to be done to avert yet another panic in the world of American investment. But as a result of these interventions, the U.S. government finally (1913) made the move to set up a government agency, the Federal Reserve, to intervene when such economic crises began to show signs of developing. In a sense, Morgan himself had shown the U.S. government the proper procedure by which to intervene when necessary, contributing greatly to the stability of the U.S. economy, which throughout the 1800s had experienced one speculative crisis after another.

|

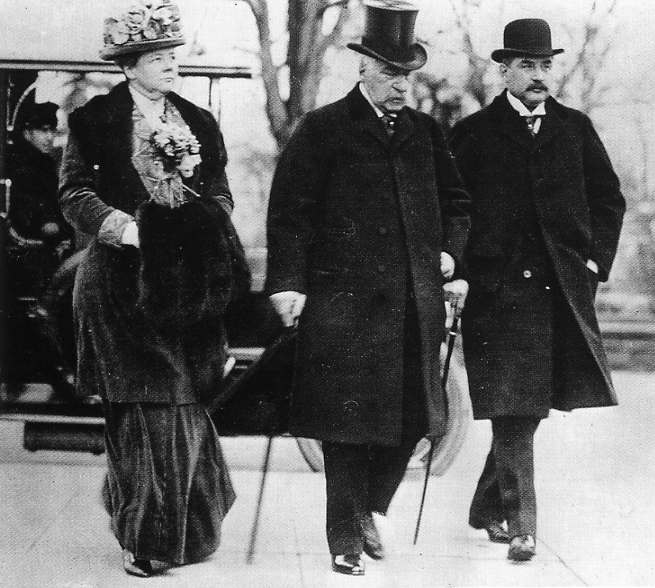

J.P. Morgan with his daughter

Louisa and son J.P., Jr.

John Pierpoint Morgan

(1837-1913)

Frederick W. Nash / William

Howard Taft National Historic Site

|

John D. Rockefeller

During the Civil War he and his brother raised the capital to found a business providing produce to the Union armies, and then the two of them in 1863 joined a team of investors to build in Cleveland's fast-growing industrial area an oil refinery designed to produce kerosene, helping to move the country away from expensive whale oil as the source of its lighting. In 1865 he bought out the leading partners of the business and through considerable borrowing put himself (and the remaining investors, including his brother) in a well-placed position within an economy turning more and more to the use of kerosene. By 1870 he moved to establish the Standard Oil Company, which quickly became Ohio's largest oil company. Then moving into the shipping business, he was able to acquire for his oil business special railroad rates that allowed him vast advantage in his competition with smaller oil companies, which he was quick to buy out when they stumbled. Then in 1874 he signed a secret deal with his largest New York competitors, Pratt and Rogers, to buy out their oil company and bring the two on his company as partners. And thus Rockefeller proceeded to move through the infant oil industry, buying out company after company until, by the end of the 1870s, Standard Oil owned 90 percent of America's oil business. He even at one point took on the huge Pennsylvania Railroad Company, starting a price war in shipping rates, which finally forced the railroad to sell its own oil interests to Standard Oil (actually Rockefeller was moving away from shipping by rail to shipping by pipeline). But this in turn brought charges of monopolistic practices (not the first time, however, nor the last) in the courts of Pennsylvania and other states. These court cases Rockefeller found himself battling constantly, gaining for Rockefeller a very negative national reputation. Adding to this negative image was when in 1882 Rockefeller set up the Standard Oil Trust, a move to bring the many separate state corporations under a single domain (at that time companies were licensed to operate within only the state granting the corporate license). Not only did the creation of this new trust produce a huge outcry of monopoly in the nation's press, other corporations, seeing the benefits of this move, were quick to set up similar organizations, birthing the age of the massive American trust companies. He also birthed the practice (taken up by New York's National Petroleum Exchange) of selling oil futures on the open market as shares or certificates based on oil held in storage, thus making the pricing of oil a public matter. Eventually Rockefeller ventured into the growing world of international oil production, then moved from kerosene production into the business of natural gas, and even the refinement of gasoline (previously considered just a wasteful byproduct of kerosene production), just as the world of automobiles, with their new internal combustion engines, was opening up. But the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act,

originally designed to break up labor organizations, would soon be

turned against Rockefeller, especially as he moved to acquire oil

fields in other American states, his vast oil fields in Pennsylvania

beginning to play out. He also entered the business of iron ore

production and shipment with Carnegie, causing a huge public uproar. But like Carnegie, Rockefeller’s business sense was based on a larger view of his responsibilities to the world around him. He never saw the making of money as evil, seeing how though some people would fall by the wayside in the competitive world of business and finance, the overall effect was clearly one of economic advancement for the society as a whole. True, some benefitted vastly more than others in this trend, but even here Rockefeller felt a sense of responsibility to his world, setting up charity organizations designed to help the young and ambitious climb to greater social heights. Indeed, this was part of his understanding of his Christian responsibilities, which began with his church tithing even as a teenager, and which interestingly included teaching Bible at the Baptist church he attended as an adult. But his charity helped turn by 1900 a small Baptist college into the University of Chicago, his grants to church mission produced the Central Philippine University in 1905, and ultimately his sense of charity led to the creation of an outstanding medical research center in New York City. In 1913 he established the Rockefeller Foundation, granting it $250 million to aid in medical research and training, and in 1918, granted $550 million for another foundation (later absorbed into the Rockefeller Foundation) for social research.

|

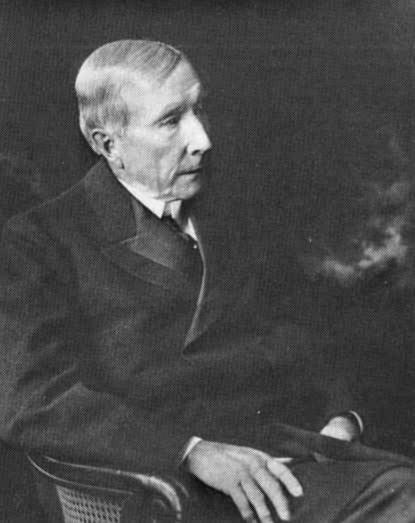

John D. Rockefeller – founder

of Standard Oil Company and America's first billionaire

Library of

Congress

John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937)

and his son, John Jr.

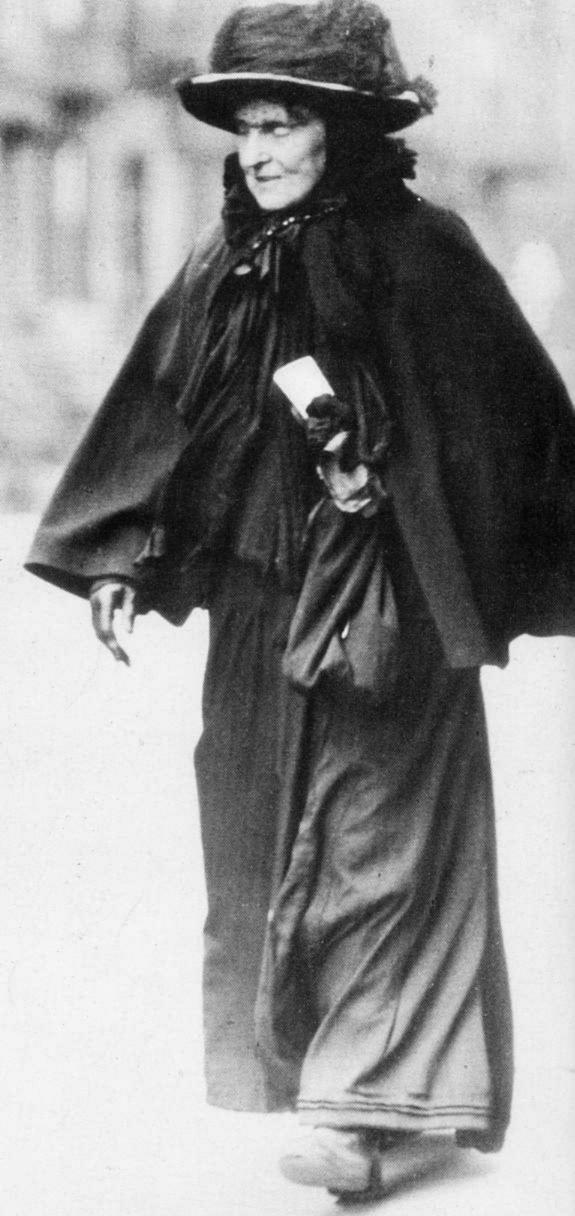

Hetty Green – America's

wealthiest

woman (and most miserly) (1835-1916)

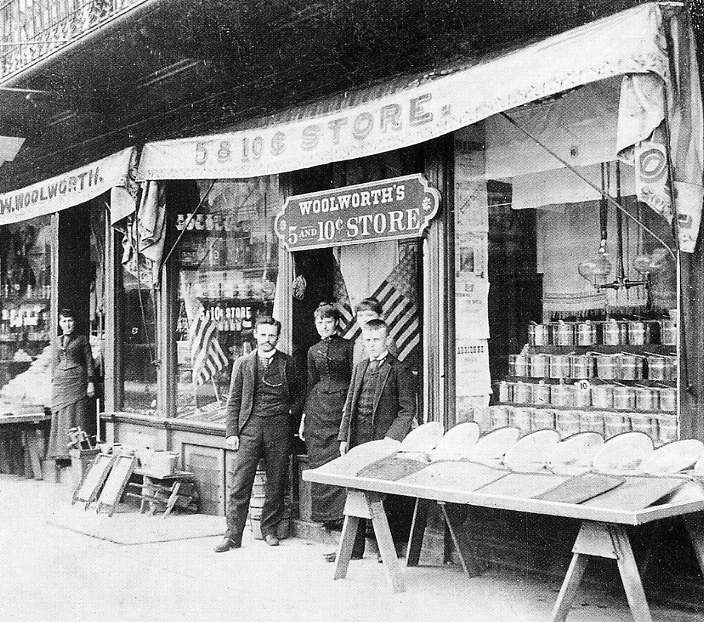

Frank W. Woolworth and his

first 5 and 10 cent store in Lancaster, PA – 1879.

At the height of his retail

chain's success it owned 8,000 stores worldwide.

|

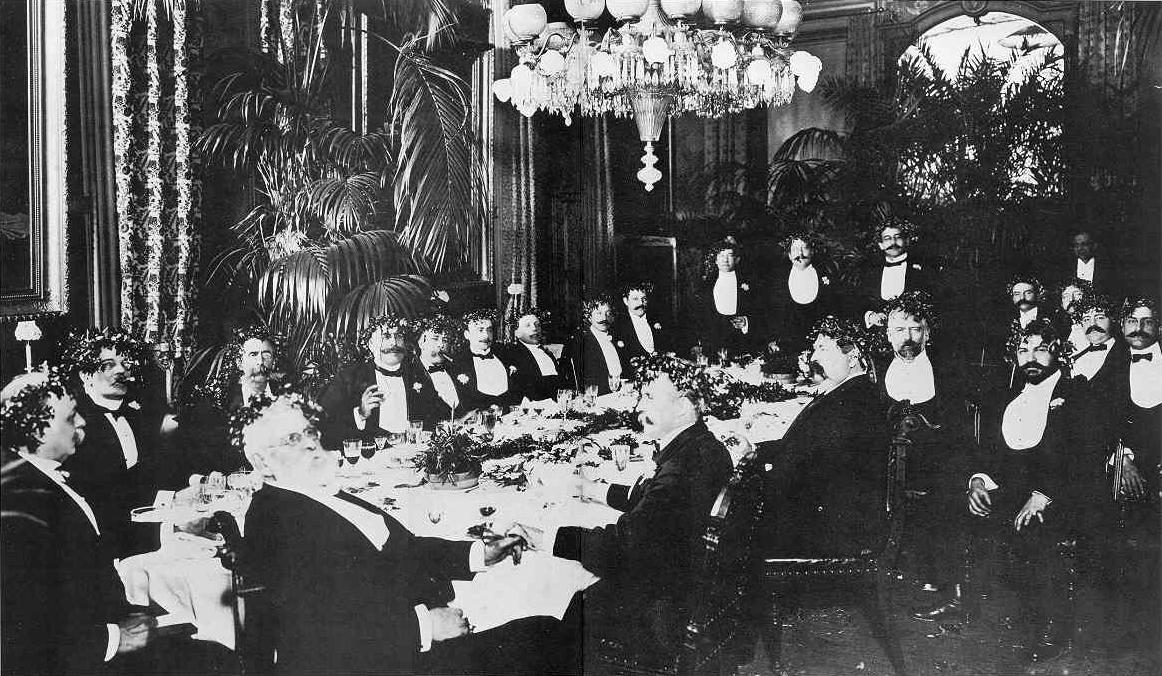

An Olympian fellowship of

America's wealthiest men

at a banquet honoring Harrison

Grey Fiske (center) – 1901

The Byron Collection, Museum

of the City of New York

Dinner on horseback at Sherry's

Restaurant – New York, 1903

Byron / Museum of the City

of New York

One of four Vanderbilt mansions

[Cornelius Vanderbilt's] on 5th Avenue in Manhattan

Cornelius Vanderbilt's summer

mansion, "The Breakers," in Newport, Rhode Island

William Vanderbilt's summer

mansion, "Marble House," in Newport

The dining room in William

Vanderbilt's "Marble House"

Promenading on the Newport

greensward

Commodore C.

Vanderbilt

Commodore C. Vanderbilt's

256-foot yacht "North Star"

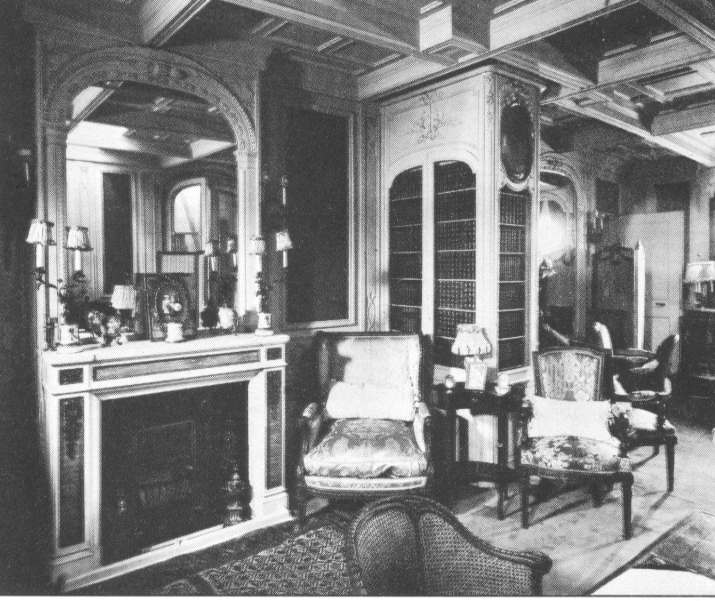

The dining room of

"North Star"

The stateroom of "North

Star"

The library of "North

Star"

Consuelo Vanderbilt (married

to the Duke of Marlborough) at the coronation of Edward VII

|

Comfortable Middle-Class

American Family – 1906

The St. Louis World Fair

- 1904

Daytona Beach, Florida -

1904

The first Rose Bowl game

in Pasadena, California – New Year's Day 1902

(Michigan beat Stanford

49-0)

The Harvard-Yale championship

football game of 1907

American League Baseball

- Boston vs. New York at Boston – 1904

Library of

Congress

The Jim Jeffries – Jack Jackson

heavyweight championship bout – July 4, 1910

|

Dana

Gibson

The Gibson girl – the idealized

American beauty created by artist Dana Gibson

Alice Roosevelt, daughter

of the President – "woman of the decade"

|

A horrible shattering of

that picture occurred in on April 8, 1906 -

the San Francisco earthquake

and fire

San Francisco earthquake

and fire, April 18, 1906

The San Francisco earthquake

and fire – April 18, 1906

San Francisco Burning – April

18, 1906

People on Russian Hill look

toward San Francisco's downtown, (including the

Hall of Justice, Merchants Exchange, and

Mills Building), burning after being

shocked by a powerful

earthquake.

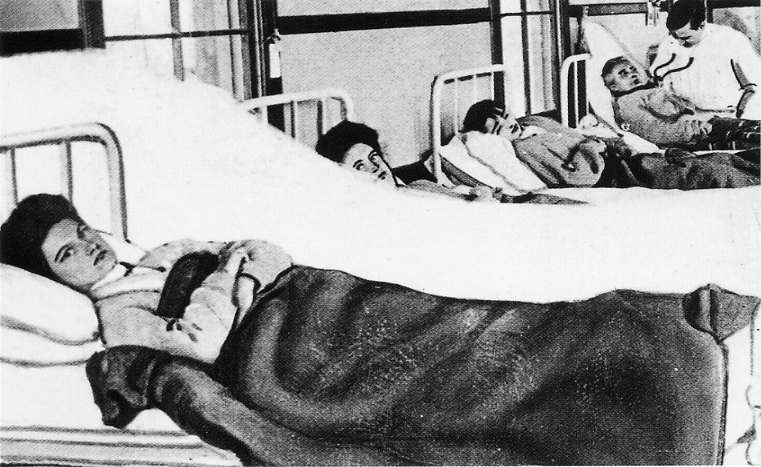

"Typhoid Mary" Mallon – a

cook for wealthy families who caught her disease.

Although she was diagnosed

with the disease in 1907, she continued to work

under various aliases until

1915 – when she was finally institutionalized for life.

Miles H. Hodges