|

|

America as a brash, young, industrial giant America as a brash, young, industrial giant

Rapidly expanding science and new technologies Rapidly expanding science and new technologies Thomas Alva Edison Thomas Alva EdisonThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 347-351. |

|

|

As powerful as the financial-industrial giants Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Morgan, and Rockefeller were, they were not the only thing powering America. There was a sense of dynamic infecting the entire country, born of the very obvious changes in the material foundations of American society. America was quite obviously joining the ranks of the great powers of the world. You did not even need to be told this. The feeling was just there. But there was indeed a factual basis for this feeling. By the time just prior to the outbreak of the Great War (World War One) in 1914, America alone was responsible for one-third of the world's total industrial production, more than Britain, France and Germany combined! That figure alone spoke volumes about what America was becoming. After all, there was evidence everywhere you looked. Yet, as the 1800s came to a close, it was generally considered by those outside America to be the Age of Europe, with European empires stretching around the world, bringing British and Dutch business practices to Asia, French culture to virtually all parts of the world, the division of the African continent into spheres of English, French, Portuguese, German and even Belgian political-cultural control. Islamic culture was in a mood to copy European ways, as was the Japanese culture as well. Europe understood itself to be the world's arbiter in the matter of what was good, what was worthy, and what was not. It is not that America went unnoticed. But it was viewed by upper class Europeans as a primitive land of cowboys and Indians, and by working class Europeans as a place to escape to in order to find work, any kind of work. None of this presented a picture of sophistication or anything worthy of social attention. Yet the fact was that America had just reached the status of being an industrial giant, the largest in the world, at about the time that Europe had reached the peak of its glory. And what Europe did not understand was that the next century (the 20th) would be a time of decline for itself. And it would also be a time when America would finally register itself – internationally – as the world's greatest power.

|

New York workers laying streetcar tracks – 1891

The Museum of the City of

New York

Construction of the New York

City subway – begun in 1902 with first station opened in 1904

New

York Public Library

|

|

The railroad industry

Railroads were encouraged to reach West across empty plains, deserts and high mountains by governmental financial incentives. But overall and even more importantly, as more railroads spread elsewhere and everywhere across the nation, it was the huge private (non-governmental) financial trusts that were able to amass the capital necessary to finance this massive construction of rail-lines. These vital rail-lines spanned the nation from ocean to ocean, from Canada to Mexico, carrying a massive amount of goods needed to fuel the huge national economy (food and raw materials headed East, finished goods headed West) built on farming, mining, manufacturing. And they carried a restless population always looking for new horizons and new opportunities in this vast nation. The telegraph and the telephone

Keeping the country linked together was also the telegraph1, which followed the railroad lines so that a flow of vital information kept up with the huge flow of goods and people across the nation. Never before had such a huge territory possessed such instant linkage, so that these massive distances from ocean to ocean found themselves melted down to the level of human horizon that only a couple of generations previously would have reached out only ten or so miles (the distance from the farm to the local town nearby). Distance seemed virtually to have been annihilated! In 1876 Alexander Graham Bell patented the phone and formed the company of his name, taking phone service in 1877 from three thousand users to 260 thousand by 1893, when his patent ended his exclusive right to operate a phone service. Then thousands of independent companies jumped into the market and soon even poorer Americans could afford the luxury of a phone. By 1920 thirteen million phones were providing service to over a third of the American households, rural as well as urban. 1In

1844 Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail built a transmitter that was able to

send by wire from Washington to Baltimore a message written in Morse's

own code.

|

Alexander Graham Bell

demonstrating

the telephone

Guglielmo Marconi (left)

his assistant G.S. Kemp – and his radio receiver – December 1901

(Marconi won the 1909 Nobel

Prize for physics for his work in radio technology)

|

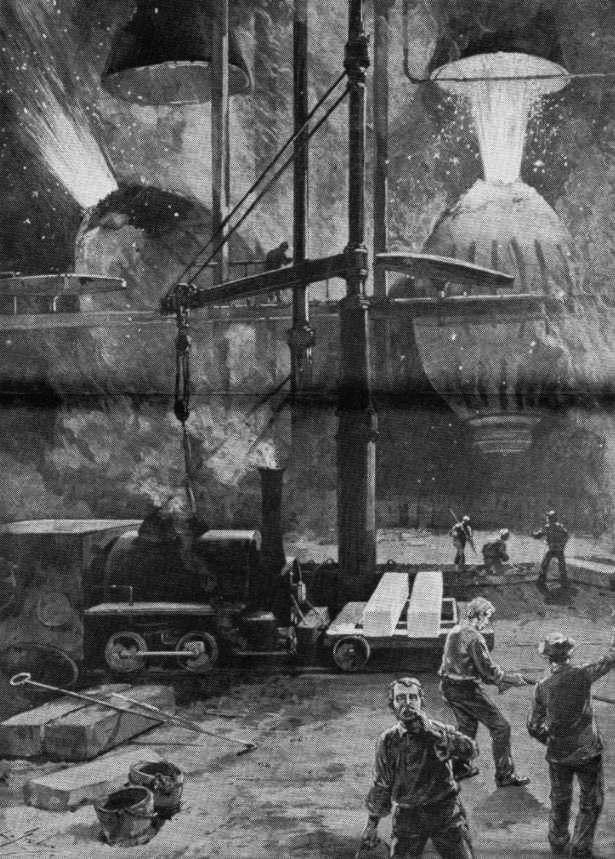

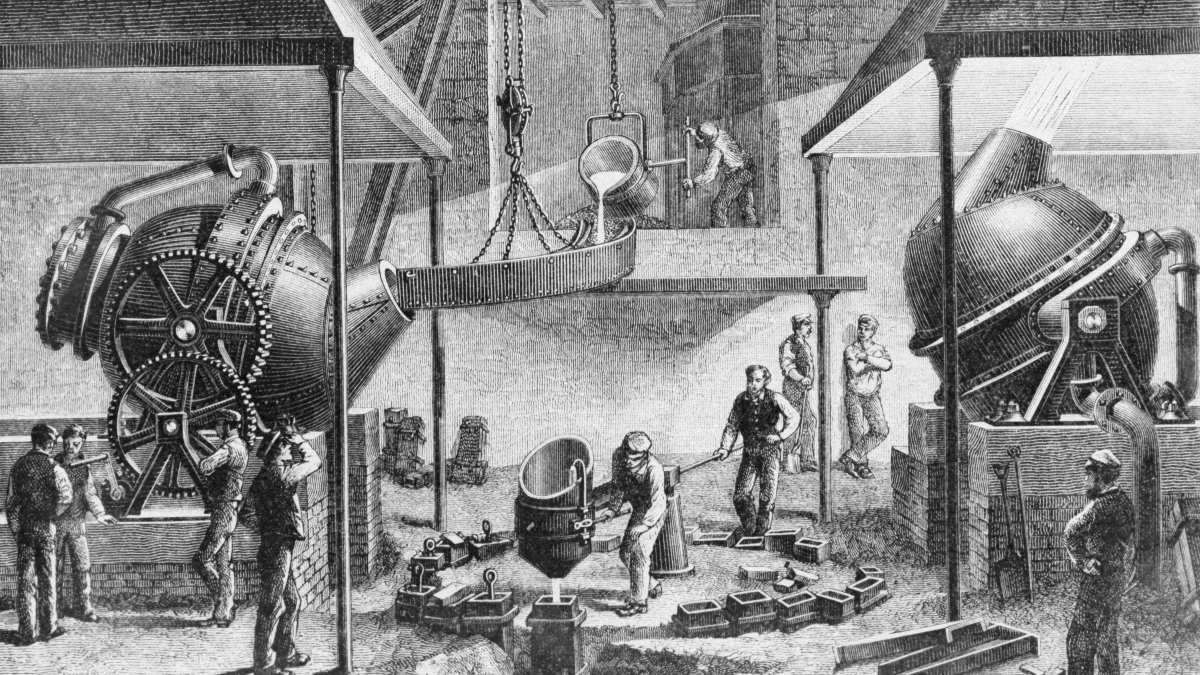

The American iron and steel industry

Of course the railroad steam engines and the vast use of iron rails called forth a massive iron industry, and from that eventually the more expensive but more sophisticated steel industry. Soon steel would be a key part of America's industrial success. From 1870 to just before World War One, America's annual growth rate in steel production averaged 7 percent (thanks in great part to Carnegie), whereas Britain's was a mere 1 percent (Germany's was 6 percent; the rate for France, Belgium and Russia, the other major steel producers, was a little over 4 percent). Overall, American annual steel production climbed from 380 thousand tons in 1875 to sixty million tons in 1920.

|

The Bessemer process of steel

making

Library of

Congress

|

The oil industry

We have already seen that the oil industry got off to a huge start when it was discovered how to replace expensive whale oil with kerosene refined from the crude oil seemingly abundant in Pennsylvania. The age of the machine also required oil as a lubricant. Then with the development of the internal combustion engine fired by gasoline or diesel fuel, the demand would grow even stronger for oil's distillate, gasoline. Gas and electric lighting

Gas lighting (distilled from coal) was already in wide use in England in the early 1800s, lighting streets (making them safer at night), factories (24-hour work was now possible), theaters (much brighter than candles), and even homes (of the wealthy, of course). America quickly caught on to the possibilities, and Baltimore (1817) was quick to adopt the use of gas for lighting. By the mid-1800s gas lighting (and the lamp-lighter who moved from lamp to lamp to light them at night) was a regular feature of America's major cities. But

gas had one major disadvantage. It was dangerous. Theaters burned down

when something went wrong with the gas distribution or lamp system.

Homes could also suffer the same catastrophe. This then led by the

1870s to electric lighting in theaters, but also in city streets and

businesses, using the electric arc system that produced a very bright

light (used also in coastal searchlights). Helping to develop this

technology into a huge business venture was the amazingly versatile

inventor, Thomas Edison (he held over 1,000 patents).

|

|

|

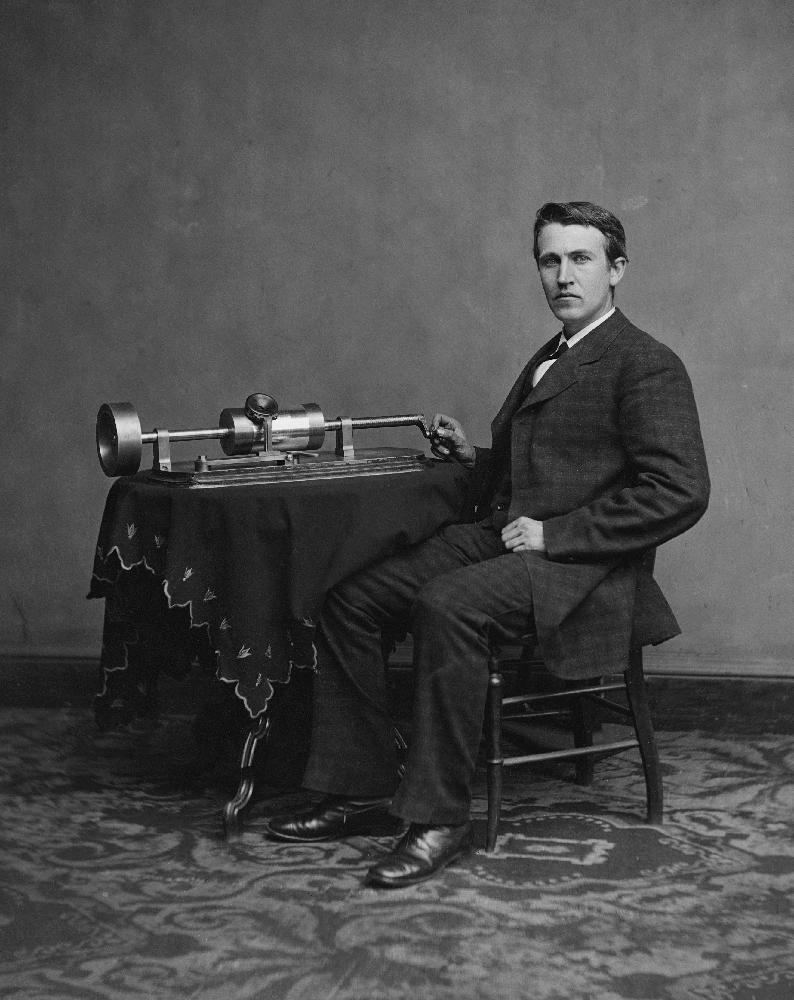

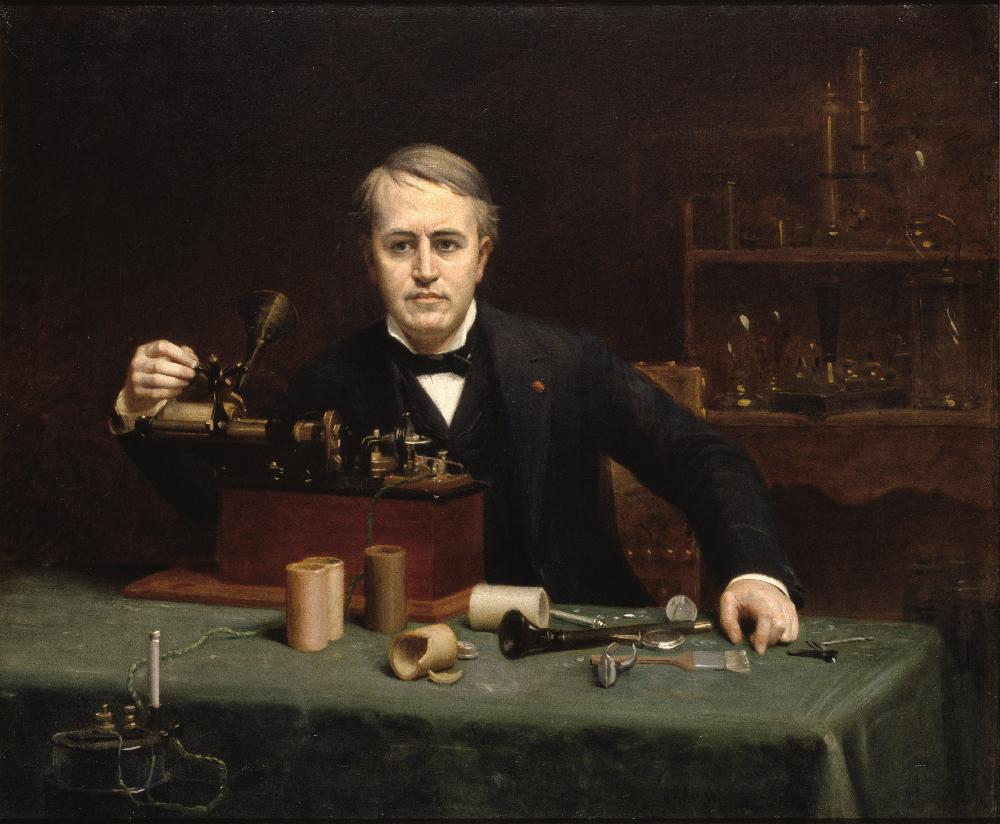

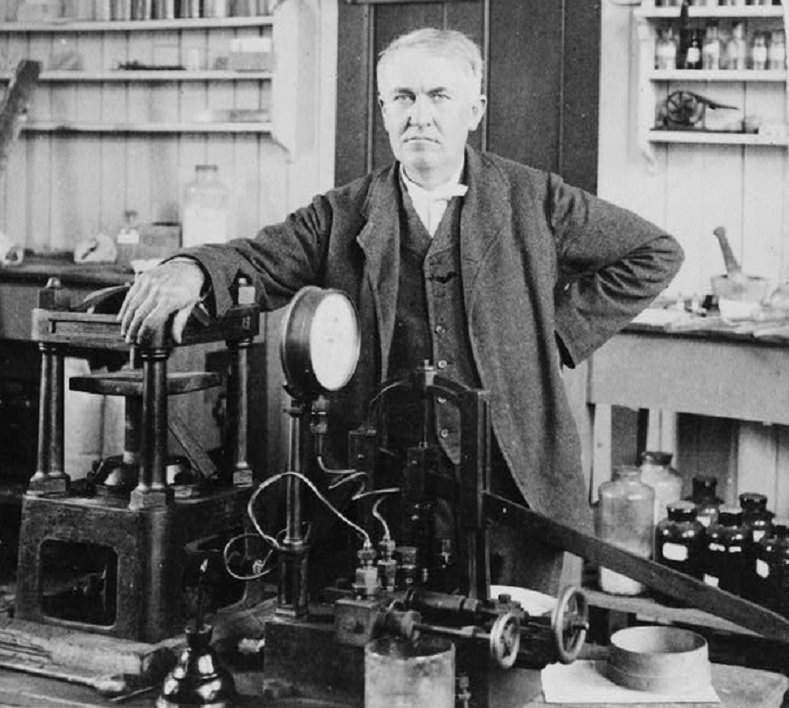

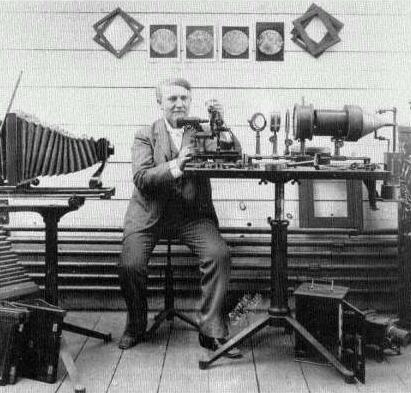

Although being hard of hearing, he went on to develop the first phonograph (1877, age thirty) on tin foil wrapped around a cylinder, being invited to Washington to demonstrate his invention before U.S. President Hayes and the Congress. He was now a celebrity inventor! He moved on to develop his own research lab (which eventually expanded to two city blocks), financed initially from a sophisticated telegraph bought from him by Western Union. Here, with the help of hired assistants, he went about the business methodically of conducting experiments involving a wide array of instruments and machines, and ultimately the incandescent light bulb. He began experimentation on such a light in 1878, the next year ran a successful test on a low voltage (thus inexpensive) carbon-filament light that lasted for over thirteen hours. With some more improvements, he was able to patent the year after that (1880) a very durable light using a bamboo filament that could burn for over 1,200 hours. He was tireless in his pursuit of invention, commenting at one point: "I have not failed, I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work"! He had an excellent eye for the business aspect of his inventions. While still conducting his lighting experiments, in order to manufacture and market his lights he set up the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City in 1878, including J.P. Morgan and some of the Vanderbilts as investors. From this venture he then went on (1880) to form the electricity utility, Edison Illuminating Company, to distribute electricity to New York City using a 110-volt generating system – establishing that as the American standard (a 220-volt system is used in Europe). Then he ran into trouble with his direct current (DC) system when George Westinghouse began to compete with an alternating current (AC) system that distributed electric power much more widely and cheaply than Edison's DC system. A corporate battle thus erupted between the two men, one that Edison was not destined to win. By 1890 he was forced out of his own company by J.P. Morgan, and the company merged with an AC company, to become General Electric (a huge AC company which then controlled almost three quarters of the electrical business, Westinghouse being the largest holder of the other quarter of the business). Edison went on to develop motion pictures, his first invention in 1891 being a kinetoscope, or peep-hole viewer. Then in 1896 he invented a movie projector able to cast a film image on a screen in front of a full audience. He even invented a recording machine able to synchronize the sound with the film. His movie projector proved to be a grand success, his film studio making almost 1200 short films, and prospering Edison greatly. He was active in other fields as well, the rubber industry, mining, x-ray (which he learned the hard way was very dangerous because of its radiation). And besides his activity in New Jersey he had a house built in Fort Myers, Florida, next door to a man who had once worked for his lighting company – and whom he took a liking to and encouraged his own development: Henry Ford. The two would remain close friends all the way until Edison's death in 1931.

|

Edison and his

phonograph – 1878

Thomas Alva Edison – by Abraham Archibald

Anderson – 1890

Washington, National Portrait

Gallery

Edison and his kinetoscope

Edison and an experimental

microscope camera

U.S. Department of the Interior,

National Park Service, Edison National Historic Site, West Orange, NJ

Thomas Alva Edison - 1922

Edison and his

staff

Edison's laboratory – West

Orange, NJ

Edison at work in his

lab

National Park

Service

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges