|

|

Dealing with the "spoils system" Dealing with the "spoils system"

The election of 1880 ...

and Garfield’s brief presidency The election of 1880 ...

and Garfield’s brief presidency Chester A.

Arthur Chester A.

Arthur

Grover

Cleveland Grover

Cleveland

Benjamin

Harrison Benjamin

Harrison Cleveland’s second term in office

(1893-1897) Cleveland’s second term in office

(1893-1897) William McKinley brings the 19th century to a

close William McKinley brings the 19th century to a

close

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 351-360 |

|

|

Presidential and congressional politics were fairly tame during the late 1800s. With the issue of Reconstruction simply fading away and with the government-financed railroad to the Pacific completed, the federal government seemed to be called on to play only a secondary role in the further development of American society. America seemed to run mostly on the basis of its own industrial-economic dynamics, rather than on the deep involvement of the Washington government in the life of the nation, such as was the case during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Social reform would be a big issue during this time. But the initiative for action came not from the halls of Congress or the White House but from the public itself. Through the publicity of America's newspapers, from books written by social reformers, from Christian pulpits, much energy would be given to the idea of perfecting American society. And it would eventually involve the national government, in the form of legislation designed to firm up a reform that the public was demanding. But in this, the government played not the initiating role but merely the confirming role. One issue however did occupy much governmental attention: the vast corruption going on within its own ranks. President Hayes had tried to clean up some of the corruption left behind by the Grant administration. But Hayes's effort to do so only weakened his position in the face of the considerable political forces benefitting from the spoils system of awarding political appointments as reward for the political support needed to bring politicians to power. The spoils system was understood simply as how politics was expected to work. To try to change things would merely upset the entire political system. But such spoils became easy targets for journalists looking for a spectacular story to uncover and report. Consequently, there was considerable pressure coming from such molders of public opinion to do something about the problem. Hayes tried to answer this call for reform when he took action to remove Chester A. Arthur from the lucrative (in terms of spoils) job of director of the New York customs-house. This brought the wrath of New York Boss Conkling, and the anti-reformist Stalwarts in the U.S. Senate who, with the Democrats, held up confirmation of Hayes's subsequent government appointments. Then the Democrats reversed the publicity spotlight, turning it on the Republican Hayes, bringing up the corrupt nature of the deal Hayes had worked with the Louisiana governor to get himself elected to the presidency. But this merely unified Republican Party support for Hayes, though it hardly appeased the press. 1This involved the assigning of government jobs and contracts as the reward for the support needed to bring politicians to power.

|

|

|

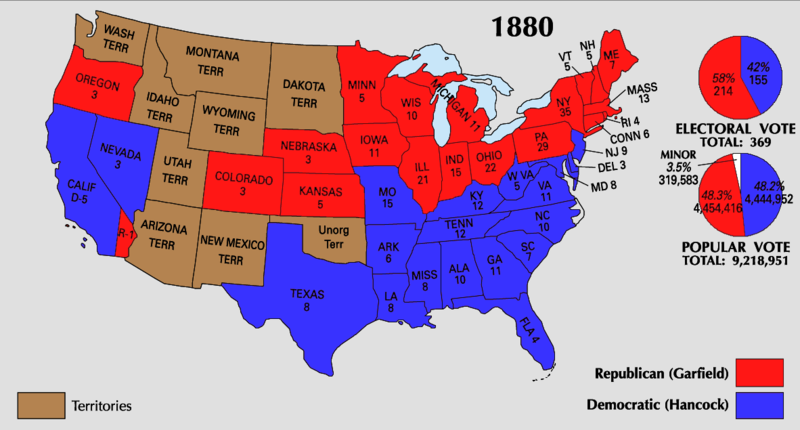

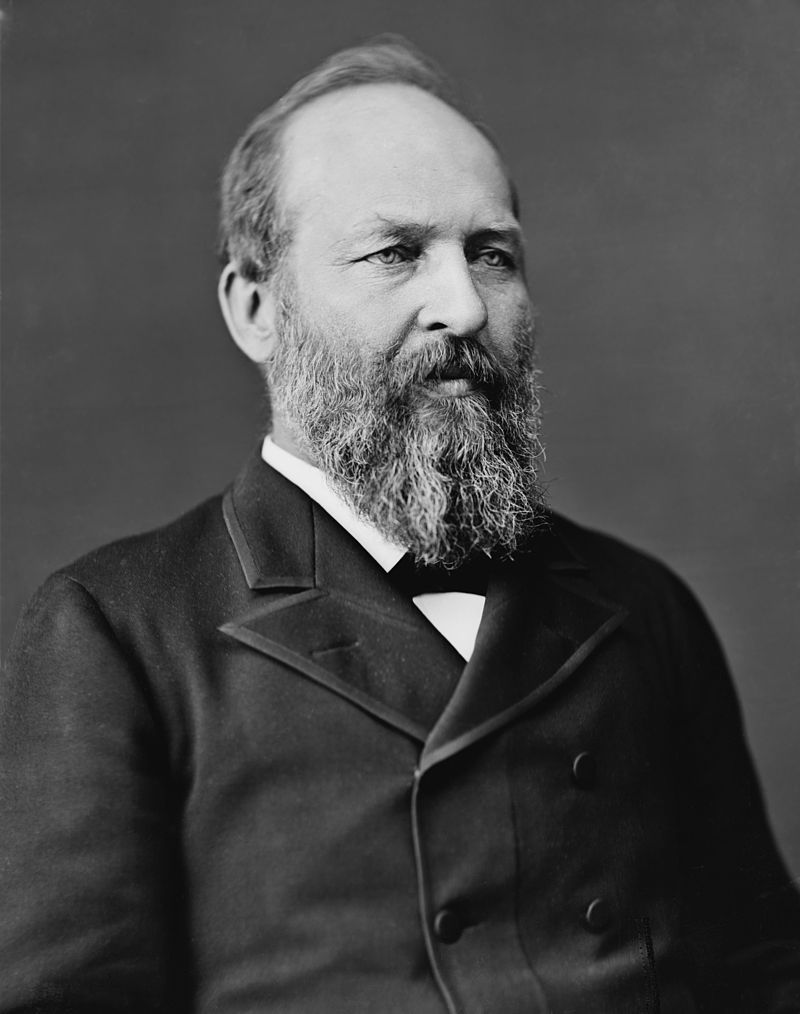

But when election-time came around again, Hayes could not muster enough support from his Republican Party to get himself re-nominated. There were a large number of contenders, including Grant, who was supported by the Stalwarts for a third term. Finally, after 36 ballots, the Republicans turned to a relatively unknown James A. Garfield, and, to Hayes’s great shock, Chester A. Arthur as his vice-presidential running-mate. Garfield was actually an excellent choice, hard-working, intelligent (once a college president), brave (rose to the rank of brigadier general during the Civil War), and politically experienced (having served in both houses of Congress). Running against him as the Democratic Party nominee was the well-known (but politically inexperienced) former Union General Winfield Scott Hancock. The election was close, except again in the electoral college where Garfield gained 214 votes to Hancock's 155. Chester Arthur's vice-presidential nomination had been the price paid to get Conkling's New York support. But once in office, Garfield had other ideas about how much he owed Conkling in patronage and worked hard to get truly qualified individuals posted to government jobs. In the end, Conkling overplayed his hand, and New Yorkers turned against Conkling. But also in the end, it was this patronage question that made Garfield's presidency short-lived. He was in office only a few months when he was shot by an unhappy and mentally unstable office seeker – and Garfield died 2½ months later of the wound doctors were unable to heal (they could not find the bullet).

|

|

|

Actually, the man who had been dismissed from his job at the New York customs house proved, in inheriting the office of U.S. president, to be one of the country's leading anti-corruption reformers. He personally vetoed bills coming out of Congress (most importantly the Rivers and Harbors Act) that were merely opportunities for more political patronage and financial corruption. He also signed into law the 1883 Pendleton Act which turned an increasing number of civil service appointments over to a Civil Service Commission charged with the responsibility of filling government positions on the basis of proven merit rather than political connections. Finally gaining the deep respect that few at the outset of his presidency ever would have expected, he nonetheless chose to retire from politics after one term in office rather than run for re-election (he was suffering from poor health). The 1884 election

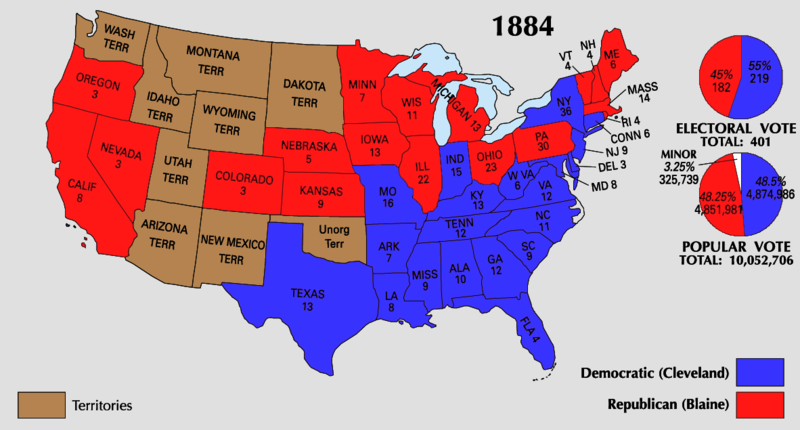

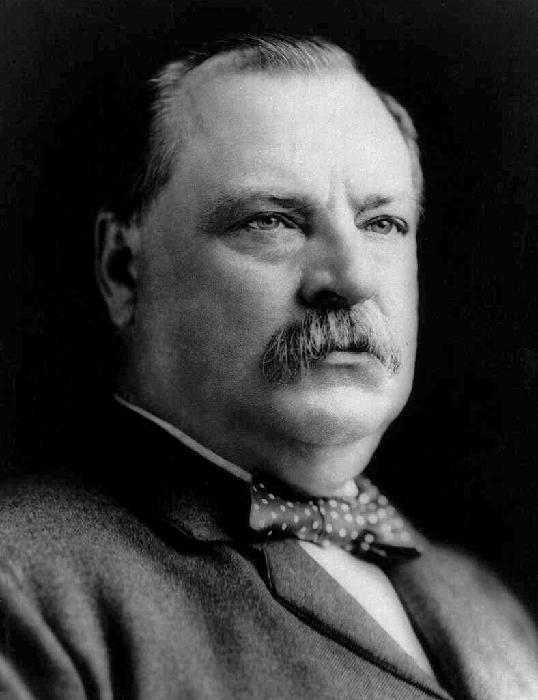

The 1884 election was fought largely over the issue of personal integrity, the Republican candidate, James Blaine, suffering from a well-known history of deep involvement in the railroad industry spoils system and the Democrat candidate, Grover Cleveland, on the other hand well-recognized for his incredible integrity – except for the claim raised by opponents that the unmarried Cleveland (but he would soon marry in the White House) had once fathered a child out of wedlock. The election was so very close that it came down to the electoral vote of New York, in which the final tally gave Cleveland a little over a thousand more votes than Blaine out of a total of over a million votes cast in New York. Part of what ended this long Republican control of the presidency was when a number of reformist Republicans, the Mugwumps,2 cast their votes for the Democrat Cleveland because they viewed Blaine as being simply too corrupt. 2From an old Algonquin term meaning "a person of importance," implying that those who bolted from the party were being ridiculously sanctimonious or morally condescending in refusing to support their party's candidate, Blaine

Chester Arthur

James Blaine

|

|

|

During his first term in office (1885-1889) Cleveland faced the usual problem of filling government jobs with personal appointments, a deep change in personnel usually accompanying the election of a new president, especially if from a different party than the previous president. But Cleveland announced that he would not remove office holders because of their political affiliation, though he did intend to reduce the size of a greatly inflated federal bureaucracy (because of the spoils system). But eventually he bent to pressure from fellow Democrats to replace some of the Republican officeholders with Democrats, though he was even then restrained in doing so by comparison to previous presidential administrations. He also tackled the job of improving the navy, by getting rid of inferior ships built by corrupt contractors. He also had much of the railroad land in the West claimed by the railroads, but undeveloped by them, returned to federal government control. And being a limited-government supporter, he cut back on the government's financial support of veterans and farmers that he felt appeared more like spoils than compassion, and which he was certain would merely set up a form of dependency on continuing government bail-outs. Gold and silver

Another troubling (and persistent) issue he faced was over this matter of the value of the national currency, the U.S. dollar. The country was caught in deep controversy over the matter of inflation, easy credit, and a cheap dollar – versus a tight money policy. Logically speaking, it would seem that this was a matter for the government's financial experts to handle. But after the Civil War this issue had become a matter of almost religious dimensions, so much had been printed and proclaimed on the subject. It had become a matter of simple faith, especially among America's large farming and industrial working-class sectors, that the road to happiness would be easy credit and inflation: to gain higher wages at the workplace or to be able to pay back a loan later in currency that was cheaper in value than when the loan was first assumed. The best way to do that was simply to have the government print dollars, lots of them. Industrial owners and financiers however were very concerned about rising labor costs and the relative loss of the value of their investments through just such inflation and therefore they wanted dollars to remain relatively scarce and thus of ever-greater value. For most ordinary Americans, the monetary theories involved in this matter were far too complex to follow, so they used the symbols of silver and gold to represent their respective positions. Gold was scarce, and the tight money people insisted that each dollar printed be backed up in the nation's treasury by an equivalent value of gold, and gold alone. Silver, on the other hand, was considered to be abundant and ever-increasing through the relatively easy possibility of more silver mining, and the easy-money people demanded that instead of gold (or at least in addition to gold) silver be the metallic basis for the nation's dollar supply. So, silver versus gold became the hot national issue, symbolizing the deeper antagonisms between the industrial workers on the one hand and the business owners on the other, between the much humbler American classes in rural America and the growing numbers of up-East financiers – especially problematic if they happened to be Jewish. In short, gold and silver became the rallying points in a growing class or social-cultural struggle tearing at the nation. Of course these tensions had complex causes, but how easy it was to sum it all up in the question of gold versus silver! And it all made for great conspiracy theories so appealing to the people who struggled to make sense of the difficult times they faced. Like Grant before him, Cleveland was a gold man. Cleveland responded by attempting to cut back on the silver coinage which the government was required to mint under the Bland-Allison Act of 1878. This cutback merely put Southerners and Westerners and their representatives in Congress in a deeply angry mood, inspiring Bland, author of the 1878 bill, to try to pass a new bill in 1886 calling for the unlimited minting of silver currency. The bill did not pass, but left a bitter issue unresolved. The tariff question

Another issue Cleveland was forced to

tackle was the U.S. tariff. Cleveland strongly opposed the high tariffs

imposed on foreign goods in order to protect the pricing of goods

produced in America. The tariff revenues collected on imports by the

government were so high (about 47 percent of the value of the product

itself) that the government was actually registering an embarrassing

surplus in its operating budget. But in trying to reduce those tariffs,

Cleveland encountered stiff opposition from congressmen fearing that

American industry might be damaged badly if those tariff protections

were lowered. Thus he got nowhere on this issue.

|

|

|

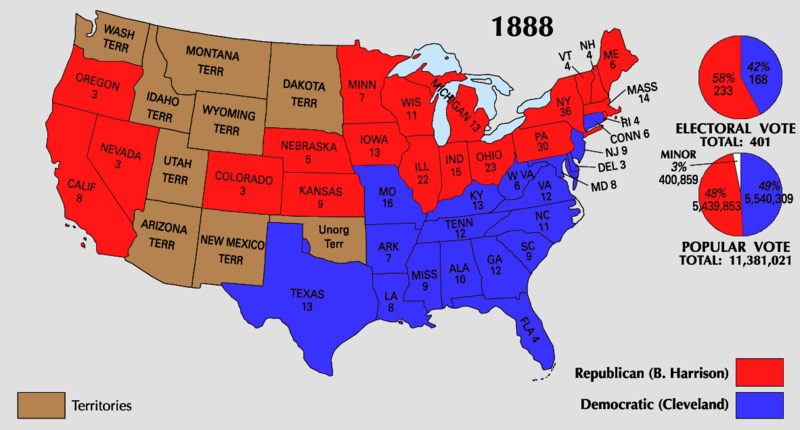

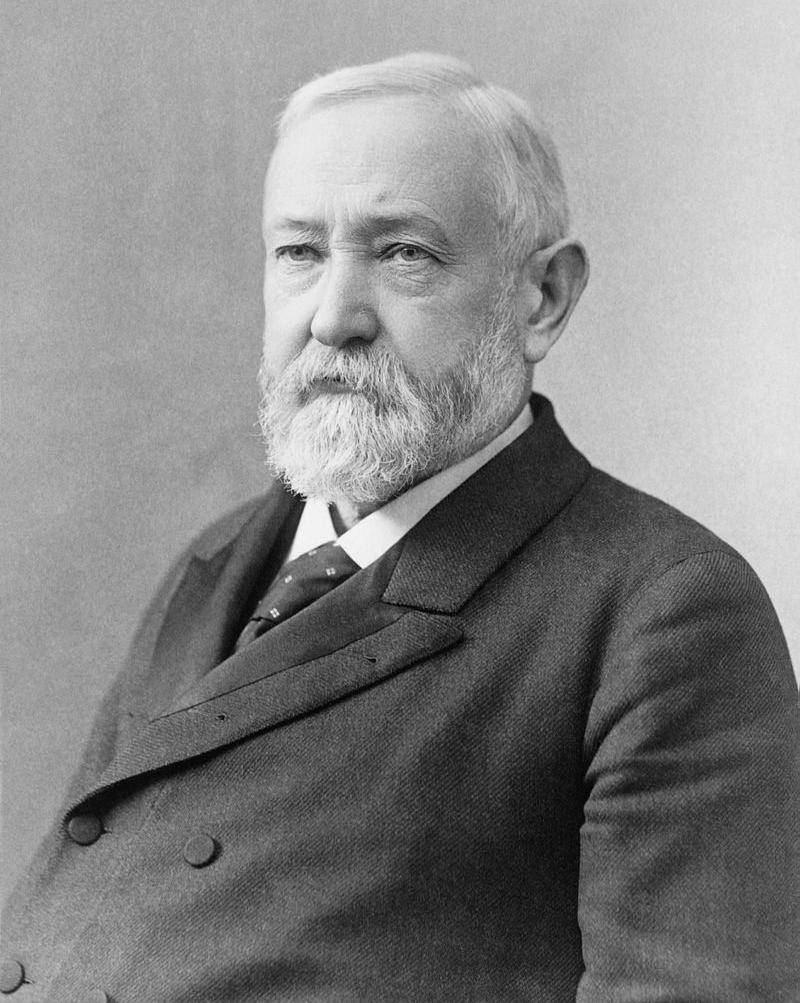

Benjamin Harrison wins the election of 1888

Although Cleveland won the popular vote in the election, he lost the electoral vote and thus his bid for a second term. A big part of his defeat occurred because of his position on the tariff issue (he lost most of the northern industrial states). Also the team of his Republican opponent, Benjamin Harrison, had conducted a very aggressive (and somewhat questionable) campaign. Cleveland even lost (narrowly) his home state of New York, because of the opposition organized against him by Tammany Hall. If a mere 600 New York votes had gone to Cleveland instead of Harrison it would have given Cleveland the New York electoral vote (and the presidency), the voting being so close. Harrison was the grandson of the Harrison who served only briefly as U.S. president before dying from a cold caught during his long inaugural address; grandson Benjamin's speech was half the length, also conducted in the rain, under an umbrella held by outgoing President Cleveland! Harrison reversed Cleveland's course with respect to the tariff and veteran pensions, but tried to emulate Cleveland in appointing government personnel on the basis of proven merit rather than mere political connections. But his idea of merit tended to favor those of his home state of Indiana and his Presbyterian church affiliation, to the anger of politicians from other parts and religious convictions of the nation. And his generous pension payments to Civil War veterans (regardless of the merit) merely opened the opportunity for graft within the Pension Bureau, and a much-criticized reduction in the federal surplus. And with the passage of the McKinley Tariff, Congress went even further than Harrison wanted to go, increasing the tariff even more, purposefully making some products impossible to import. In answer to the clamor of farmers and miners, Harrison stood behind an Act sponsored by Senator John Sherman, thus the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. Government purchase of silver had long been a goal of the farming world, and to this was added the voice of the mining world which was panicking because of the oversupply of silver produced by the metal's easy availability. The price of silver dropped away (making it even more attractive to debtors as currency) putting the silver mining industry in a panic. Silverites wanted full acceptance of silver as currency backing, at a fixed rate (well above the actual market value of the metal). Sherman did not meet the full expectations of the Silverites, but did commit the government to a fixed amount of silver purchase, helping to keep the silver market from collapsing and confirming the government's commitment to silver as currency backing. This was not a good long-term solution to any problem – and would ultimately serve as a major contributor to the Panic of 1893. On the more positive side of the

political ledger during Harrison's presidency was the antitrust

legislation sponsored by the same Senator John Sherman (the Sherman

Antitrust Act as it has been known subsequently) which Harrison signed

into law in 1890. Actually, the motivation behind the law was

originally aimed as much at organized labor (labor unions) as it was at

the huge financial trusts that controlled a great deal of the American

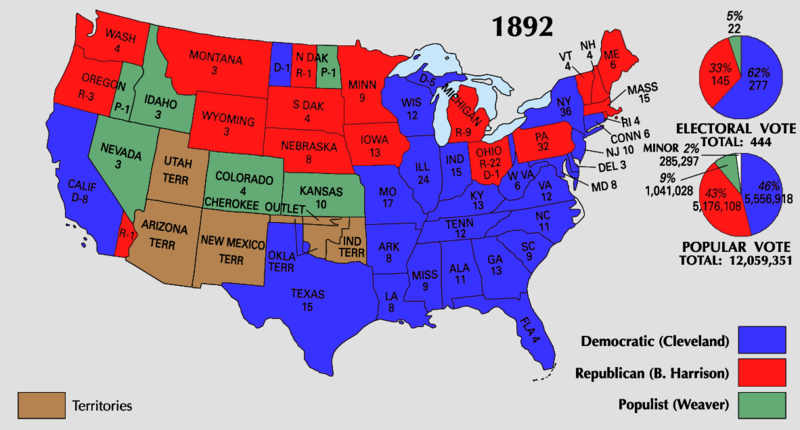

rail, steel and financial industry. But towards the end of his presidential term the economic picture of the nation was worsening (just ahead of the Panic of 1893). Things were not looking good for his re-election. Republicans had already lost seats in the 1890 elections and Harrison was experiencing the loss of support by members of his own party (many still upset over the lack of government appointments by Harrison). Also American producers were awakening to the fact that the McKinley Tariff was hurting themselves badly as consumers. As a consequence, though re-nominated by the Republican Party, Harrison faced the national election without the party support nor the popular enthusiasm needed to retain the presidency. Harrison found himself facing his old opponent, the Democrat and former President Grover Cleveland, replaying the same issues as four years earlier. But unlike previous elections this one would be clean, and quiet. In the end, the 1892 election would prove to be a sad event for Harrison, not only in losing the election rather decisively but also his wife to tuberculosis just two weeks prior to the election itself.

|

|

|

Cleveland returns to office just in time for the Panic of 1893!

A combination of bad economic news that hit at about the same time (early 1893) caused a run on America's scarce gold supply, leaving the federal treasury nearly out of gold and facing financial default. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad had become too ambitious and instead found itself in deep debt, so much so that just before Cleveland was sworn into office in March of 1893 the railroad company declared bankruptcy. This was combined with a huge drop in wheat prices, a major international income earner for the nation. Nervous investors, both at home and abroad, holding national and corporate bonds began to demand banks, including the U.S. Treasury, to exchange their bonds for gold. Seeing this trend, others jumped in quickly, including the holders of silver coinage – which was greatly overvalued because of the nation's huge silver production stimulated by the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Seeing the Sherman Silver Purchase Act as

part of the problem, Cleveland convinced Congress to repeal the Act,

ending the requirement of the government to purchase a fixed amount of

silver. This in turn caused the price of silver to drop drastically,

hurting people who held cash reserves in silver (which included a lot

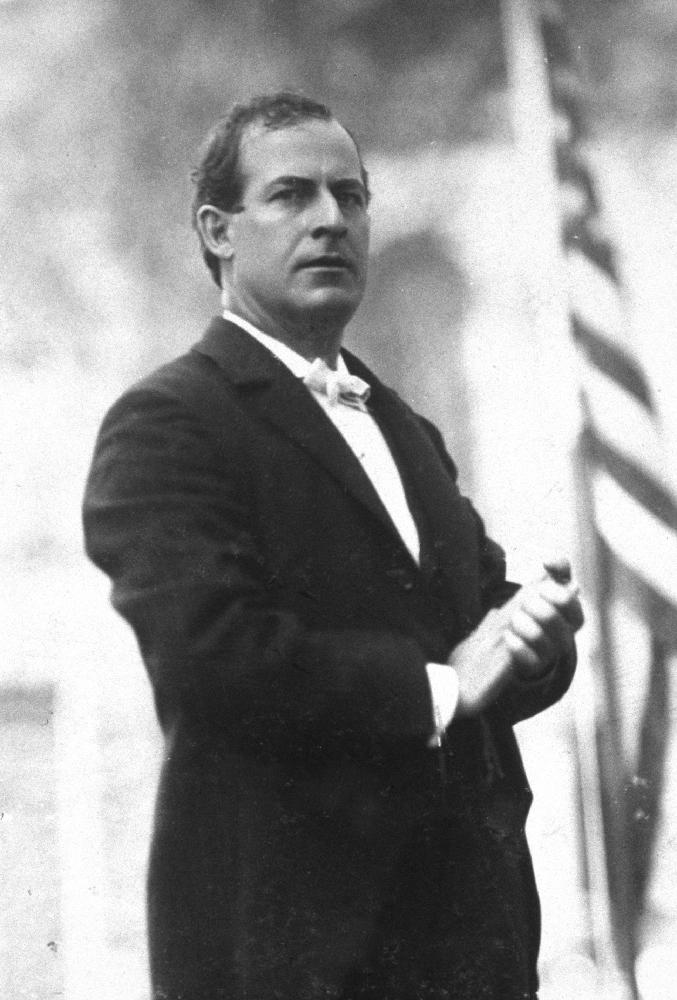

of people!). Labor unrest rocked the nation. In 1894 Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey led a march of unemployed workers on Washington. Many dropped out along the way and the final demonstration was fairly tame, though it certainly alerted the nation to the growing discontent of the U.S. workforce. More violent was the Pullman Company strike by workers (organized by the Socialist leader Eugene Debs) demanding an end to the policy of low wages and the twelve-hour work day. The strike quickly spread to other railway workers until by mid-1894, 125 thousand of them were on strike, virtually shutting down the U.S. rail network. Since the trains carried the mail, Cleveland went after the strikers for violating federal law, resorting finally to sending troops to various points across the nation to make his point. Meanwhile, Cleveland's assault on the silver market led the Populists (widely popular among American wheat and cotton farmers) to claim that undercutting silver and trying to rebuild the nation's gold holdings was simply an international conspiracy – predominantly Jewish – designed to destroy the American economy. However, at this point America was bleeding its gold reserves badly, not rebuilding them. Then the formidable J.P. Morgan proposed to Cleveland that he would join with the Rothschild bankers of Paris to sell the government 3.5 million ounces of gold (about $65 million in value at the time) in exchange for thirty-year bonds. As previously mentioned, at first U.S. President Cleveland turned down the offer but finally in 1895 accepted Morgan's offer. Thus the U.S. Treasury was spared default. The 1896 elections

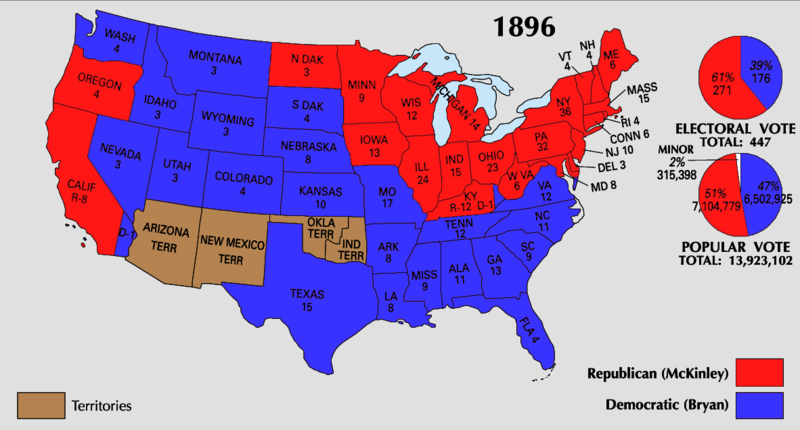

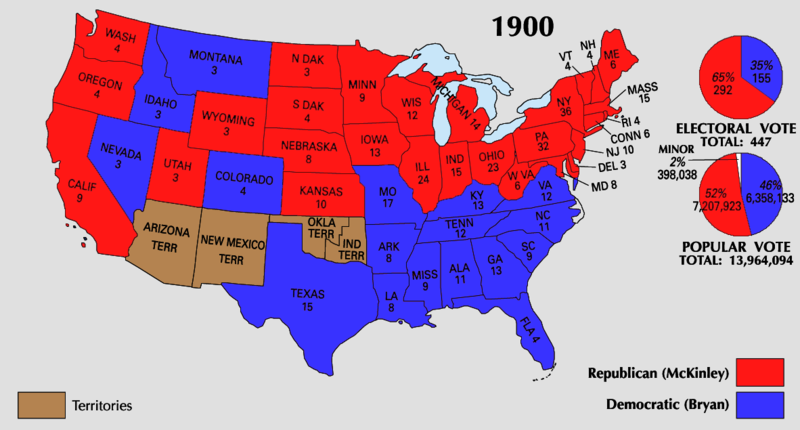

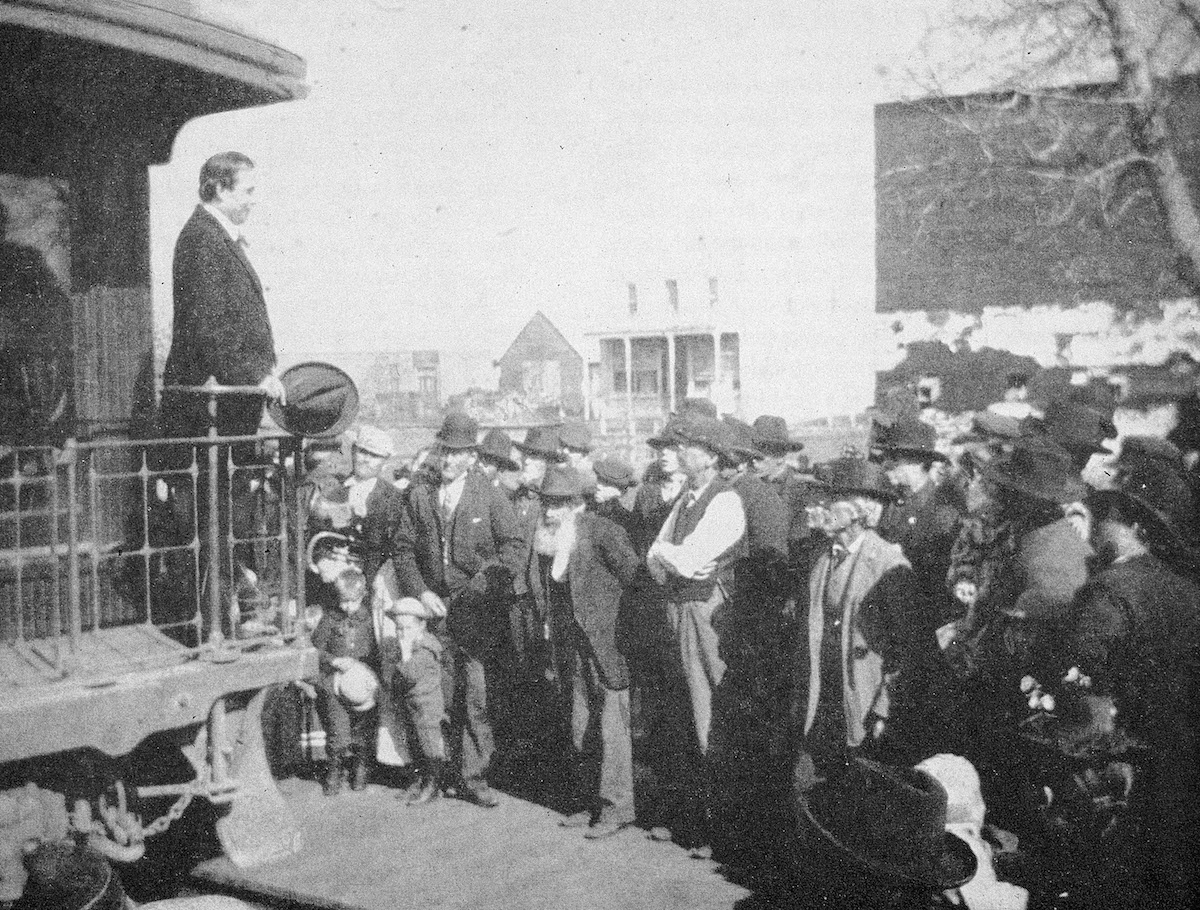

Cleveland's efforts to resolve the complexities of the Panic seemed merely to undercut his standing with the agrarian and labor wings of his Democratic Party, which suffered a huge setback in the 1894 Congressional elections. Then when in the summer of 1896 the Democratic Party gathered to nominate a presidential candidate, Cleveland was faced by William Jennings Bryan, of the strongly populist and Silverite wing of the party – a fiery orator who roused the convention with his challenge, "you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold." Bryan was subsequently nominated by the Democratic Party, and Cleveland went into political retirement at Princeton, New Jersey (becoming a trustee of the university). 3Estimates are that 500 banks and 15 thousand businesses failed during the 1893-1898 years of the Panic.

|

|

|

He had been an Ohio lawyer elected in

1876 as a Republican representative to Congress where he sponsored the

McKinley Tariff protecting American industries from overseas

competition. He lost his seat in 1890 with the huge Democratic victory

of that year, but the next year he was elected Ohio governor and again

two years after that (1893). As governor he gained a reputation as a

skillful mediator between business and labor, and his very skillful

political campaigning for the Republican Party in 1892 and in 1894

brought much party attention to him as a possible future presidential

candidate.

Protective tariffs and the gold standard

As president, McKinley made good on his campaign promises, signing into law in 1897 the Dingley Tariff, offering strong protection of American industry, and in 1900 the Gold Standard Act, establishing gold as the sole standard in the redemption of the dollar, making the dollar very strong, and expensive (the gold standard was dropped in 1933 as one of the first acts of Roosevelt's New Deal). American imperialism

But it was in the area of foreign affairs that the most notable feature of the McKinley presidency stands out. America had long been taking a protective interest in the events occurring to the South of the country in Latin America. But a rebellion in Cuba by those seeking independence from Spain became a major political issue in America when the uprising turned particularly brutal. In 1898 McKinley led the nation to war against Spain, eventually securing not only Cuban independence (under American protection) but also full American possession of the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. And on top of that, it was during McKinley's presidency that America seized the Republic of Hawaii as a new U.S. territory. The election of 1900

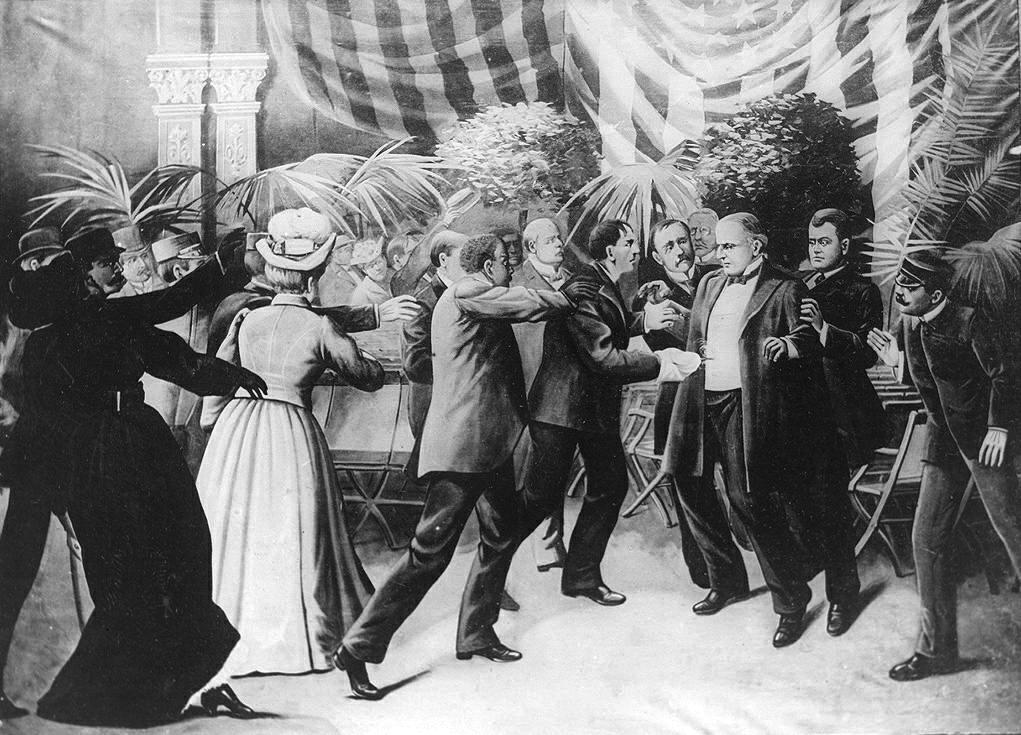

Although the campaign might have appeared as a replay of the 1896 election, America had changed greatly during the four years of McKinley's first term. The nation was experiencing a "Full Dinner Pail" as the Republicans termed the prosperity that the nation was experiencing. Also American victory in the war with Spain had American pride (and support for their president) running strong. And Bryan's running on the silver platform now had none of the impact that it did in 1896. Also his criticism of American imperialism under McKinley lost him a lot of national support. Otherwise the campaign style did not change much, Bryan on the road delivering endless speeches and McKinley greeting visitors from his porch in Ohio. And the results were again the same, although McKinley registered a slightly larger majority of the votes than in the previous election. Thus McKinley took office for a second four-year term. But McKinley was only six months into his second term when he was shot in the stomach twice by a deranged anarchist at a presidential reception at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. A week and a half later he died of his wounds. The insignificant Vice President Roosevelt was thus thrust into the office as the nation's new president. This would move the pace of political change started under McKinley even further, much further.

|

Miles H. Hodges