|

|

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 366-371. |

|

|

The social challenges prompting the Progressivist Movement

It was certainly very easy to be excited about the times. The changes in life-style had been so amazing, so extensive, and in such a short stretch of time. In only a couple of generations Americans had gone from horseback to automobiles, and even to flight. Electricity lit up not only cities but also homes, news of the larger world arrived almost instantly to an increasingly attentive population, personal phones put people in direct communication with each other across even the miles, and wealth reached down into even the middle classes, who knew that they were living better than kings and queens had lived only a few centuries earlier. All this change was very heady stuff. But there clearly was a downside to all this change. The American population was climbing rapidly. In the forty-year period between 1870 to 1910 the population went from 38.5 million to 92.3 million, growing by about 25 percent each decade (28 percent by 1880, another 27.6 percent by 1890, and another 21 percent for each of 1900 and 1910). This time period also marked a huge shift in the nation's demography, 10 to 11 million (figures are not exact) Americans moving from farms to America's fast-rising cities, where they were joined by another 25 million immigrants streaming in from Europe. Not everyone headed to the cities was going to find the streets paved with gold. On the contrary, urban slums – with all the accompanying problems of filth, disease, violence and just simply human degradation – greeted the vast majority of these urban pilgrims. Also with over fifty percent of the nation's total wealth owned by one percent of the population and nearly a half of the population owning only one percent of the nation's total wealth, it was a certainty that there was going to be a huge outcry about this outrageously huge social disparity in the land where supposedly "all men are created equal." This in itself gave sufficient cause to those with a crusading heart to take up the cause of social justice. Thus developed a rather spontaneous and very diverse social and political movement which historians have termed Progressivism. Progressivism was not the program of any

particular social group or even political party. The state itself

played a rather minimal role in its many initiatives, although the

state did tend to follow up on social initiatives in many cases with

legislation solidifying the gains of the Progressivists. The church

also played a minimal role, although much of what moved Progressivism

was the Christian conscience. By and large Progressivism was the instinct of crusading individuals – and groups which these individuals were able to gather around their particular social cause. These individuals were often writers and journalists, they were often educated and socially comfortable individuals with a crusading zeal for social reform, and occasionally they were political leaders.

|

|

|

The basic features of the Progressivist Movement

The Progressivist Movement actually took on many dimensions, sometimes some of them seemingly a bit contradictory. A good example of the contradiction rested in the desire to give the state wider powers to regulate the economy to make it more fair or just to all, yet at the same time the desire to place the state under greater democratic control because of the widespread corruption that seemed to accompany the widening powers of government at that time, especially at the local and state level (though by no means was the national government itself exempt from such corruption). It was no secret how party bosses ran huge political machines that controlled local politics, especially in the growing industrial cities. Thus Progressivism sought to make local government more democratic and more efficient (also often contradictory concepts!) by introducing the ideas of popular recall of corrupt public officials, the party primary which allowed the voter rather than the city machine to choose the local candidates for public office, even the idea of hiring a professional city manager who would supposedly be neutral in the realm of party politics. Progressivism was also very focused on finding remedies to the corruption that also infected urban and industrial society in general. Progressivism attempted to place restrictions on child and women's labor in the factories and mines. Indeed, Progressivism demanded better working conditions for all laborers. Progressivism was dedicated to the goal of improved public education, especially for the poor living in urban slums. It fought for quality control of foods, especially meats, sold to the public. It pursued a fight for greater protection of the natural environment against the wholesale plunder of the nation's natural resources. And it included the ideas of turning prisons into reformatories that would reform rather than just merely punish offenders of the law. Christian Progressivism

Many of these Progressivists were profoundly inspired by long-standing Christian ideals. To them this sad social development pointed to a huge loss of the original Puritan vision that had set the country out on a mission to be a city on a hill, to be a light to the nations, showing the world how the sovereignty of the people was supposed to work. For many Christians, especially some of the Evangelicals within the Christian community, Christ called them to go out into the broken world, teaching, preaching and healing – in order to bring up the quality of the people's lives, in preparation for Christ's second coming – the Millennium – which they believed was imminent.1 To such Evangelicals, Christian action was needed now, to avoid the wrath of a God who had every right to expect his people to better the world they had been given. With Christ's second coming, judgment of all people was going to be swift and sure. Secular or Humanist Progressivism

Others reacting to the social problems around them were more inspired by the rising Humanism that had captured numerous American hearts. These Humanists were generally intellectuals – writers, journalists and educators for instance – who cared somewhat abstractly for the category of those less fortunate than themselves. Their caring generally took on the form of calling for social justice through governmental action or legal reform. Such Humanism was very Rousseauian, in that the Humanists had little doubt about the basic goodness of man – if given the right opportunity to demonstrate that goodness. All that stood in the way of bringing this human virtue to light was a corrupt society built on corrupt laws and consequently corrupt social practices. According to the Humanists, society needed only to reform the social laws that enabled and encouraged these corrupt practices, and the utopian bliss which they were positive awaited mankind would dramatically appear. God's justice played no role in this matter. It was all simply a case of employing human logic – or social science, as this logic came to be termed. 1Actually,

there was something of a big divide within this community of Christian

Evangelicals or Millennialists. Progressive Christians tended to be

Postmillennialist in believing that the thousand-year reign of Christ

(the Millennium) would come only after a fully successful conversion of

the world had taken place, a matter requiring ever-greater effort of

Christians to bring Christianity and its civilizing qualities to the

world. The Premillennialists on the other hand believed that only a

time of great tribulation (not human progress) would announce the

arrival of the Millennium – requiring of the faithful spiritual

vigilance, rather than the progressive works of the Postmillennialists.

|

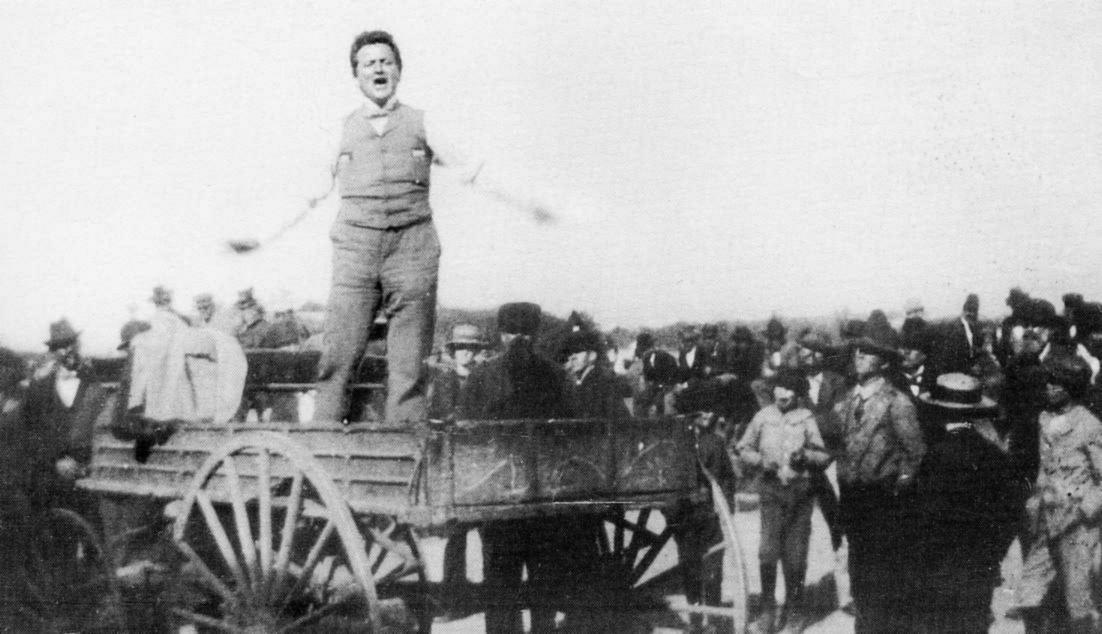

Another well-known and very ardent Progressivist was Wisconsin Governor Robert La Follette

Blind and deaf Helen Keller, her teacher Anne Sullivan, and prominent actor Joseph Jefferson

Upton Sinclair – whose novel

The

Jungle aroused Americans against filth in the meatpacking

industry

Ida Tarbell – exposed corrupt

business practices of the Standard Oil monopoly -

1902-1904

Lincoln Steffens – exposed corrupt city politics in a number of American cities

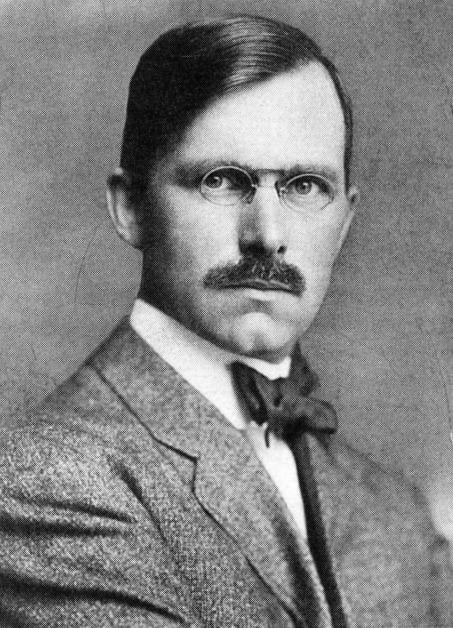

David Graham Phillips

Constitutional

reformer and crusader against corrupt national politics (early 1900s)

Ray Stannard Baker – exposed

the Atlanta News' role in inciting the 1906 race riots

|

|

The first and foremost problem that Progressivism felt needed to be tackled was that of relieving the suffering of those whose lives had been thrown into turmoil by all the industrial change. This group of industrial victims included the small farmers who found themselves unable to compete with the larger industrial farms arising in their midst, industrial farms that were able to secure special rates from the grain elevator companies that stored and prepared the farmers' grain for shipment, and special shipping rates from the single (thus monopoly) railroad company that connected their region to the customers back East. To the smaller American farmers, who were having a hard time earning a living from their small plots of land, this special treatment extended to the wealthy industrial farms was outrageously unfair. Something needed to be done to curb the power of the high and mighty, and restore power to the small American farmer, the mainstay of American Middle-Class society. This category included also the industrial workers who worked long hours in the newly-rising enterprises which hired their services or labor. Skilled workers were accustomed to being respected for their special industrial talents, and were unhappy that their services were so poorly compensated in comparison to enormous earnings of the financial managers or owners of the enterprises that contracted their services. In another way, they were incensed when they were gradually reduced in status simply to that of laborer, hardly different from the masses of unskilled labor who poured into the industrial cities looking for work of any kind. This latter group of unskilled laborers was actually itself divided into a number of different groups. One was that of the Anglo-White laborers, usually former farmers or their sons unable to secure or hold their lands in the increasingly competitive world of American farming, Whites that were driven to the cities to find any work that they could. Another was that of the Southern Blacks who came North looking for work, no different from the White farmers turned laborers – except for the sadly major distinction of skin color. And then there were the European immigrants (and on the West Coast the numerous Chinese) who came to the country with virtually nothing except the hope that they would finally find success in the America whose streets (they were told) were paved with gold. This labor mix was characterized by powerlessness in the face of the wealth (and consequent political power) of the industrial elite, or "robber barons" as both the laborers and their spokesmen among the Progressivists termed them. It was also characterized by confusion and disunity within the ranks of the workers because of these many social divisions that set one labor group off against the others. United, they could have constituted a major political force. And indeed many Progressivist reformers attempted to do just that, unite the American labor force into a single labor movement. But in the highly diverse America, that would prove to be an almost impossible task. The Knights of Labor

An example of the difficulty organized labor faced was the Knights of Labor, founded in 1869. Because of its strong advocacy of the eight-hour working day, it had reached a membership total of almost 30,000 members by 1880. Four years after that its membership figure reached 100,000 and then two years after that (1886) nearly 800,000 members, making it by far the largest labor organization in America at that point. But the organization itself was weak. And although the Knights of Labor was politically republican in character, it became identified in the press and by its capitalist adversaries as a dangerously militant organization in the manner of the anarchists, who were very influential among many of the immigrant German and East European workers. Indeed, this unfair comparison crippled the organization after the disastrous Haymarket Square Riot of 18862, with most of its members soon abandoning the organization. By the time of the economic Panic of 1893 it had become only a very small operation. The American Federation of Labor (AFL)

The organizing of American labor was subsequently taken up by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) founded in the pivotal year of 1886 by Samuel Gompers as a result of a dispute with the Knights of Labor over competing labor contracts. It united a number of guilds or unions of skilled workers and craftsmen (as opposed to common day laborers) – beginning with the cigar makers' unions. Then as the Knights of Labor faded away during the later 1880s, the AFL held steady, even picking up new members. Overall, it supported the idea of capitalism, simply attempting to put skilled workers in a better position to take advantage of the huge profits being accumulated in the industrial revolution sweeping America.

2At

a gathering of workers at Haymarket Square in Chicago who were

demanding the eight-hour working day, an unknown person threw a bomb at

police who were in the process of dispersing the crowd, killing seven

officers and a number of civilians. On the basis of scanty or

non-existent evidence seven (mostly German) anarchists were sentenced

to death by hanging (a number of them had not even been present at the

gathering) for their contribution to the tragedy. Only four were

actually hanged, as one committed suicide in jail and the two others

had their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment, but were

pardoned by the Illinois governor in 1893 who (as did many) considered

the trial a total travesty of justice.

|

|

|

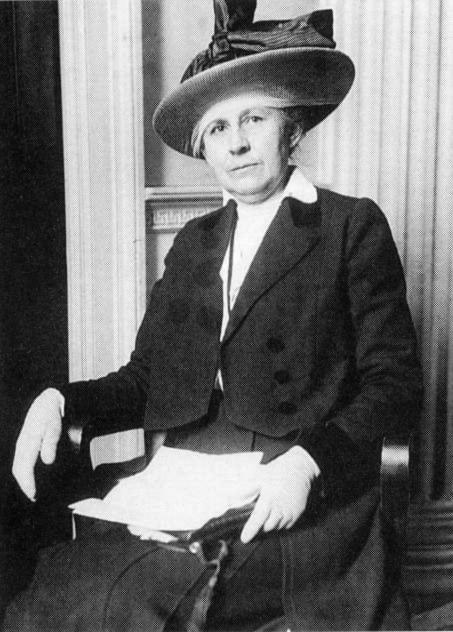

The anti-alcohol crusade

American Progressivism also included a very strong women's – even feminist – movement. For a number of American women, the prohibition of the sale of alcohol easily brought them to political action. Far too many husbands were returning home from work on payday completely empty-handed, having stopped at the local bar along the way to find some liquid joy in their hardscrabble lives. All too often this visit to the bar was as far as their paycheck got them, leaving their wives to wonder how they were to pay for the food and the other requirements of their meager lives. Something needed to be done to solve this problem, to halt the scourge of rampant alcoholism. In this, women particularly put the moral

muscle of Christianity behind their efforts – eventually generating the

idea that any alcohol-drinking at all was un-Christian (a rather recent

Christian virtue – although drunkenness had always come under strong

Christian condemnation). And thus the Women's Christian Temperance

Union (WCTU) was born. Women's voting rights Right along with this anti-alcohol movement went the issue of women's suffrage (voting rights). In most states, women were not given the right to vote. Voting was considered an expression of the will of the entire family – men, women and children – which men, as head of the family, were supposed to represent in voting. But the women claimed that men were not handling that responsibility well and therefore the vote should be opened up to women, who as mothers and wives would bring a more moral tone to politics. The more radical among the feminists of those days however pushed for voting rights simply as a matter of social justice, a right that should flow from the basic natural equality of men and women, regardless of whether or not it better-served American family life.

|

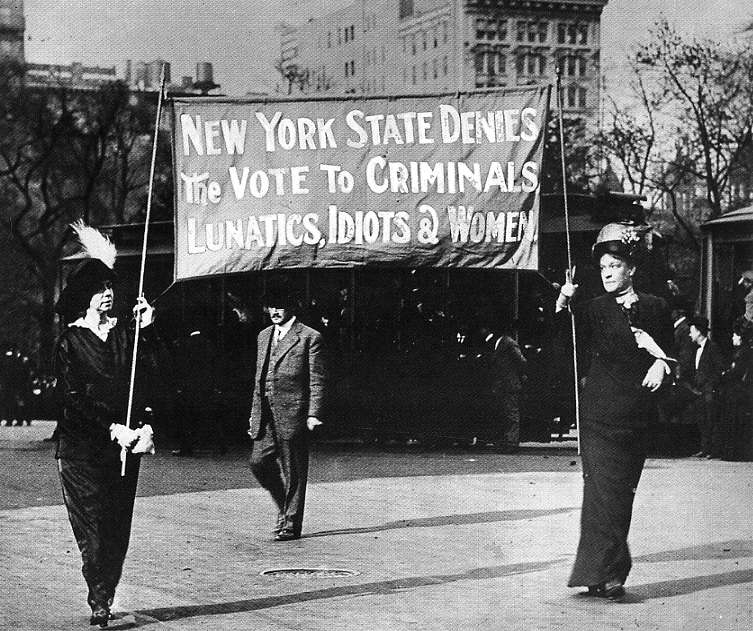

One of the hottest reform issues of the day was women’s suffrage – and other women’s rights

Suffragettes marching on New York City Hall – 1908

Suffragettes demonstrating

in Washington, D.C. – 1914

New York women protesting

the lack of voting rights

(in 1917 their state extended

limited voting rights to women)

Margaret Sanger – birth control

advocate

- 1916

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges