|

|

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 415-425. |

|

|

Democracy as the rising ideal of American politics Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, as we have just seen, America was developing its own new thoughts on the matter of society, and how progress could be brought into play to make for a much better world. Interestingly, much of the American individualistic mindset found itself easily forming around this term that about this time was gaining great currency: "Democracy." Democracy in the American context was not

Marxist, Socialist or even particularly Darwinist – as was the case

generally in Europe. But it did have strong elements of Rousseauian

utopianism in it. And it seemed also to be a natural fit to the spirit,

the mood, of America as it entered the 20th century. American Democracy

was built on the instinctive idea of the full sovereignty of the

millions of individuals that made up American society. They alone as

individuals were responsible for their futures. They alone governed

their lives. They were truly members of a great Democracy. Democracy or Republic? Thus it was that

with the arrival of the 20th century, Americans began more frequently

to refer to their society as a democracy rather than as a republic.

Probably Americans thought that the two were the same thing. The term "republic" makes reference to the question of ownership of the political system or government of a people. It comes from the Latin res publica, meaning "thing of the people." It is similar to the old Anglo-Saxon word "commonwealth," meaning the wealth or property of the commoners or ordinary citizens. This term "Commonwealth" is still in use in America in reference to the state governments of a number of the states that were once part of the original thirteen colonies (such as the Commonwealth of Virginia, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, etc.) It was also the title that was assigned to the government of England for the brief period (1649 to 1660) when England was without a king but was ruled by a Puritan Parliament and its Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. A republic or commonwealth is simply a government that belongs to the people. How it operates is actually yet a different question.

The term "democracy" makes reference to the question of how a political system works, who rules it and how. A democracy is the type of government of a society in which the citizens rule their community directly – that is, when all governmental decisions are made by the people themselves. Certainly America has a democratic tradition in that in the early days of the American colonies each town was ruled directly by an assembly which brought all the adult males together to make that town’s vital decisions on all sorts of matters, political, economic and spiritual. But beyond the local level, and really only in the early days of the colonies, there has never been much democracy in America.

American government is more properly termed a "representative" government, in which the powers of government are performed by representatives of the people. This has a democratic feel to it in that these representatives are often (though by no means always) elected and thus ultimately accountable to the people at some point for their performance in office. Elected representatives need to have their mandate renewed periodically (re-election). But many "representatives" of the people are not elected at all – such as judges and members and officers of the civil service and the military – but are appointed by office holders. |

|

|

Rousseauian Idealism

A big part of the confusion over the idea of

democracy is that since the early part of the 20th century high-minded

Americans began to take on the old and well-failed mid-1700s idea of

Jean Jacques Rousseau, that democracy is some kind of natural political

condition of man – natural in the sense that if it were not for the

corruptions of a bad culture or a corrupt government, people everywhere

would live freely, lovingly, on the basis of a deeply instinctive

desire to live peacefully in fellowship with each other as equals. That

is, they would live democratically. They needed no autocratic authority

to force them into social compliance. They could live together freely,

strictly on the basis of their own personal instincts towards social

harmony. So, according to Rousseau – and most utopian Western intellectuals since then, including a growing number of American Progressivists (and virtually all 20th century American hippies!) – democracy is supposed to be instinctive to man. And one day, through our evangelical efforts to spread democracy to the world, we will be able to bring our world to a state of perpetual peace by having everyone living democratically – that is, freely. It was and is a beautiful, utopian dream. Man's self-serving instincts But it was and is a dangerous dream because it is built on an entirely naive understanding of human nature. It is an idea built on a great illusion. Man is, by all natural instinct, self-preserving and self-promoting. This is how all people start out life as babies, highly demanding of attention to their personal needs. Their survival demands that. And that same sense of selfishness is vital to the process of socialization. Man is able to live or function socially only because he is taught (as he grows up) that by living in cooperation with others, he will actually improve the benefits he personally draws from life. Thus as he matures, he is taught by social authority how to cooperate with larger society in order to draw its tremendous benefits for himself. The teaching process begins at an early age (the terrible twos), in his very first social context, that of the family (a family presided over by an authoritative mother and father). He then continues to learn through schooling to extend this realm of social self-interest by cultivating a deeper sense of social self-discipline. If any part of this process fails to take place, the individual will have a hard time coping with the demands of social life and will not know how to "do adult" and find a productive place in society. Tragically, he might even fall into what society terms criminal behavior. In short, the Rousseauian ideal, if actually undertaken, will result not in democracy but in anarchy, an anarchy however which will in no way resemble the beautiful anarchy dreamed of by the utopian anarchists!

|

|

|

Concerned about "popular tyranny" Indeed, it is important to note that the Framers of the Constitution were definitely not intending to create a democracy. For whatever reasons – partly historical (remembering how the Athenian democracy had been manipulated by Sophist demagogues who could move the gullible Athenians to support self-destructive policies and actions), partly Puritan, partly Aristotelian – they were not believers that pure democracy was possible … or even desirable. The earlier Puritan understanding of man's inherent selfishness or sinfulness – and Aristotle's teaching about the susceptibility to tyranny of any kind of government, including democracies – made the Framers very cautious about turning all power over directly to the people. Checks and balances They had built on the developing British parliamentary system of the 1600s and 1700s, one that the French political philosopher Montesquieu had pointed out (and Madison reaffirmed in The Federalist Papers) afforded all sorts of checks and balances against any one particular kind of political impulse (rule of one, of the few, or of the many) securing a dominant or controlling – or tyrannical position – in the governing program. Power was cautiously allotted to this and to that part of the governing system, without it being concentrated in any one particular position. Power was purposefully spread widely across all these various political impulses to ensure that no power holder, not a presidential monarch, not a Congressional oligarchy, not an enlightened Federal judge, but especially not a democratic mob, could establish a controlling grip over the system. To allow that to happen would be to allow tyranny to develop. No indeed. This was no democracy – nor for that matter an oligarchy or certainly even a monarchy that they had created but instead was a mixed-system Republic, one designed to best serve the whole society, present and future – for hopefully a very long time. Representative government Representative government (as close as they got to democracy) was really provided for originally only in the House of Representatives, where the citizens were allowed a direct vote for their representatives in Congress. The Senate was understood to represent the states and their governments, the two Senate seats each state was to receive generally being appointed by the state governors or elected by members of the state legislatures (the original Constitution did not specify how the states were to come up with their two senatorial representatives). In any case the U.S. senators were not originally intended to be elected by the people (the Seventeenth Amendment ratified in 1913, "democratizing" the Senate, would change that). Likewise the Chief Executive officer, the president, was not to be elected directly by the people, but by the states, each state awarded special electors in the same number of their senators and representatives in Congress. These electors would be the ones who would elect the president (how the states were to choose their electors was also originally left up to the states to decide). And the federal judges were not elected by the people but were appointed by the president, subject to a confirming vote of the U.S. Senate. Limited official or "state" government Furthermore, the national officers were given only very limited jurisdiction – that is, they were permitted to govern only in very specific areas. All other government functions were left to the state legislatures as their exclusive right to perform. Thus originally America's national democracy was quite limited in scope and subject to the checks and balances of the other branches and levels of the federal government, "federal" originally meaning the whole plan, including the huge governmental role reserved to the states as part of the federal system. It must be remembered that the government set up by the Framers was actually a military-political alliance among thirteen independent-minded states, unifying them in the face of a threatening world outside of their own, such as the British wanting to come back to retake them, one by one – or even by greedy French or Spanish monarchs hoping to do the same. It was never conceived as a government that would rule over the internal affairs of the thirteen states, as the Tenth Amendment states quite clearly. The Framers neither desired nor needed such a government. They were very determined on that matter, having just gone through a huge war against the British King George III who had in mind to bring the thirteen colonies under his direct rule as their enlightened lord and master. The self-serving instincts of the powerful of society And yet this would always be the temptation of the powerful, to bring the less enlightened ones of society under the better rule of their natural superiors. Such is always the temptation of the Enlightened Ones, who have fed themselves on the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Such self-awarded enlightenment is the worst of all human sins, for it gives the Enlightened Ones the false impression of being sacred and all-powerful, like gods.

|

|

|

However, the original American caution concerning unchecked democracy began to be set aside in the early part of the 20th century. In part this development was the outgrowth of the Progressivist Movement, as America became very self-critical of the many corruptions in American government and society, and always on the lookout for improved ways to bring to the surrounding society. The government as economic and social referee

Rather naturally, it was to the national

government that reformers ultimately looked, in the hope that wise

legislators might remedy America's various social problems. And indeed

the national government did just that, at least to the extent of

stepping into the game of laissez-faire capitalism in order to referee

the behavior of capitalism's prime players in the market place – thus

the government's trust-busting of the financial monopolies that had

come into ownership of huge sectors of the American economy. But

governmental reforms also included the safeguarding of the lives of

America's workers, and the inspection and enforcement of standards of

quality of the agricultural and industrial products sold to the public. The primary system The government also began to put pressure on urban bosses to be open and fair about how elections and political business were conducted in American cities. The party candidates for public office were usually selected behind the scenes by party bosses. But in a move state by state over a period starting in 1902 and involving all the states by 1915, candidates for office came to be selected through the primary system, where the voters themselves were given the right to select (vote for) the candidates of their parties. To this key democratic reform was added the ideas of popular recall of corrupt public officials. And finally, to move urban government to work along more professional lines was added the idea of hiring a professional city manager who would supposedly be neutral in the realm of party politics, and simply supervise the functions of urban government on scientific principles! And in early 1913, two new Amendments to the American Constitution went into effect, ones designed to give both the voter and Congress new powers, thus enhancing democracy. However, these Amendments would also lessen greatly the effect of the checks and balances of the original Constitution. The Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution (1913): direct taxation

The Sixteenth Amendment gave Congress the right to expand its ability to function on its own by allowing Congress to tax directly the incomes of Americans. This would give Washington a new independence of operation from the states, which were viewed as too dependent on party machines and thus supposedly (supposedly by the Progressivists anyway) more susceptible than Washington to political corruption. The power to tax is of course a great power – and the Progressivists had just given the government in Washington extensive powers not previously possessed. What they did not realize was that they had not solved the problem of corruption but had simply transferred the potential for that problem from the states to Washington – for they failed to understand that corruption always finds a path to wherever power is located. The Seventeenth Amendment (1913): popular election of senators

The Seventeenth Amendment also diminished the power of the states by democratizing the U.S. Senate, making it now a body of government officials elected directly by the people rather than directly by the States. Again the supposition was that it would operate more responsibly if it were answerable directly to the people rather than to the states and their political machines. This was widely understood at the time to be an excellent idea – this idea of democratizing further the operation of American government, discarding the suspicions of the original Framers of the American Constitution who held no particular form of government, including democracy, to be ideal. And certainly democracy was ideal – as

long as the people themselves were sophisticated in their understanding

of the process of national government, remained vigilant with a

detailed following of national politics, and were not easily

manipulated by clever voices that could spin ideas and turn hearts

easily. The Progressivists were confident that a well-educated

electorate – under proper guidance (namely that of the Progressivists

themselves) – could meet all these high standards. The support of ever-centralizing power

But in doing this, this changed the very

constitutional nature of American government from being a federal union

of states (as in the United States) and instead a democratic republic

(as in all modern dictatorial Socialist or Communist systems claiming

to be People’s Democratic Republics). This would remove one of the key

pieces in the Constitution put there by the very wise Framers of the

Constitution to check the growth of accumulating central power founded

on democratic political instincts, well known in history to be so very

easily manipulated by demagogues. Indeed, the French soon (1789)

clearly – and violently – demonstrated this problem inherent in pure

democracy. This Seventeenth Amendment now opened the way for the Washington government step by step to override the states' role in governing the internal affairs of the country, which indeed was the purpose of this Amendment. And justified by supposedly the more Progressivist political professionalism found in a political bureaucracy which could now take its place in the nation’s capital in Washington, D.C., this amendment would gradually take real government from the hands of the people themselves, instead, leaving the democratic masses increasingly dependent on the political favors coming their way from the Washington political professionals. Thus the irony of "democracy," repeated so often in the coming 20th century: Lenin and Stalin's Russia, Hitler's Germany, Mao's China, Castro's Cuba, Kim's North Korea for instance ... "enlightened" dictatorships claiming to best serve the interests of the people!

|

|

|

His early years

Wilson was born in 1856 to a Scots-Irish Protestant family, his father having moved from Ohio to the South to pastor Presbyterian churches in Georgia and South Carolina. Wilson was just four when the Civil War broke out, and his slave-owning father became a key leader in the Southern breakaway from the national Presbyterian Church (his father would lead the Southern Presbyterian church as its Stated Clerk from 1865 to 1898). After the war, Wilson lived in Columbia, South Carolina, where his father was a professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Schooling

Wilson's schooling started late (perhaps

from a problem of dyslexia) but he disciplined himself to compensate

and developed strong academic skills as a result. Wilson started his

college studies at Davidson College in North Carolina (his father

taking up a pastorate there in the meantime), but had to drop out

because of illness. He transferred the next year to Princeton, taking

up the study of political philosophy and history, also becoming deeply

involved in collegiate debate. After graduation from Princeton in 1879

he took up law studies at the University of Virginia. But again, health

issues forced him to return home to North Carolina. There he continued

his law studies, took and passed the Georgia bar exam, but after a year

of law practice found the work uninteresting and decided in 1883 to

pursue doctoral studies in political science and history at Johns

Hopkins University. Doctoral studies

Here he wrote his doctoral dissertation, revealing himself to be a Democratic Idealist who could find no good reason for the American Constitutional checks and balances system. In his doctoral dissertation, Congressional Government (1885), he judged the checks and balances system as . . .

manifestly a radical defect in our federal system that it parcels out power and confuses responsibility as it does. The main purpose of the Convention of 1787 seems to have been to accomplish this grievous mistake. The "literary theory" of checks and balances is simply a consistent account of what our Constitution makers tried to do; and those checks and balances have proved mischievous just to the extent which they have succeeded in establishing themselves. [p. 186-187] He made it clear in his study that he preferred the parliamentary system of the British, which had a more "responsible" form of political authority in command of the political system. He viewed the American Constitution as terribly pre-modern and its checks and balances system as a formula designed merely to produce political stagnation and corruption. What modern Constitutional government required, he believed, was a strong hand at the helm of state. In this, Wilson's thinking followed closely the line of other democratic idealists (including Marx and Lenin) who advocated revolutionary change to a system in which strong but enlightened leadership would serve as the people's advocate, thus qualifying it as very effective democracy. The fact that this easily opened the doors to popular dictatorship somehow escaped the understanding of these political scientists. Professor Wilson

After marrying the very artistic Ellen Axson (daughter also of a Presbyterian minister), the Wilsons moved to New York for Wilson to teach history at Cornell University (1886-1887) and then Bryn Mawr College (1887-1888), then Connecticut Wesleyan University, until 1890 when he was offered the Chair of Jurisprudence and Political Economy at Princeton. "Democratic politics would work better under a greatly empowered national leader" By this time he had eased up a little in his negative view of the legacy of the Founding Fathers. But he never seemed to back down on his view that American politics should be more like the British Parliamentary system in that it should be directly under the control of the national leader, through his command of the dominant political party dedicated to supporting the high principles set forth by that leader (Wilson's Constitutional Government of the United States - 1908). This lofty view of government by a principled leader would always remain at the heart of his idea of how politics should work, a position he himself eventually would take as American president, when he attempted to govern the country from just such a lofty position. He was in fact a strong advocate of an activist government empowered to correct the ills of society, and published a number of articles and books over the next dozen years (actually at the time quite well received in intellectual circles) advocating exactly just such a government. Princeton president

His writings had attracted the interest of

other universities, the University of Illinois (1892) and the

University of Virginia (1901) asking him to serve as their president,

offers which he declined. But when Princeton asked him to serve as

their new president in 1902, he accepted the offer. As Princeton

president, he proved himself to be an active developer – programs,

buildings and endowments developing rapidly under his leadership. He

also worked hard to broaden the religious view of Princeton from beyond

mere Presbyterian theological conservatism – and the student body from

being a community of young gentlemen gliding through with a C average

to being instead a community of serious scholars. He demanded more,

much more of the school, cutting way back on the traditional religious

activities expected of the students and introducing instead broader,

more humanistic studies for them to focus on. Needless to say, he got

some pushback from some of the professors for his reforms. Nonetheless, In 1905 he represented Princeton at a huge gathering in New York City of various Christian leaders interested in promoting and formalizing interdenominational cooperation in their conduct of world missions, both at home and abroad (this conference would lead three years later to the creation of the Federal Council of Churches). Wilson himself spoke of the need to make "the United States a mighty Christian nation, and to Christianize the world." But ultimately he would take up the path not of Christianity's personal salvation mission but instead a more Progressivist or "democratic" social mission to the world – something by this time that had come to be known as the "Social Gospel." Ironically this "democratic mission" would come to be directed by a man (himself) with a very autocratic personality! In fact it was this autocratic personality that ultimately found him opposed by various faculty and board members in his reform efforts at Princeton. A crisis developed because he was just not a person cut out to find a way to win people to his ideas through diplomacy. Wilson would not accept anything less than full compliance with his ideas of reform. New Jersey Governor

Finding increasing opposition in academia, his thoughts began to turn to the idea of public office. And, oddly enough, New Jersey political bosses began to look with interest in Wilson as someone they might want to run for the 1910 state race for governor. He agreed to run, and they agreed to get him nominated as the Democratic Party candidate for governor (which they easily delivered to Wilson). Thus he resigned his position as Princeton president in October, just shortly before the November elections. And in November he easily won the election over his Republican rival. Now as New Jersey Governor, he was in a position to pursue political reform – exactly according to his own ideas of what needed to be done. He was bold and unyielding in his attack on the party bosses of New Jersey, the same ones who had brought him to power! He instituted the primary system which allowed the ordinary voter to bypass the urban bosses in selecting electoral candidates themselves for public office – striking a blow for democracy. Wilson elected U.S. president (1912) Thus after only a short term in office as governor, his work was recognized sufficiently for his name to be put forward as a possible Democratic Party presidential candidate for the 1912 national elections. After much campaigning for the office himself, plus some critical last-minute support from Bryan at the convention – and after forty-six ballots – he was nominated as presidential candidate by his Democratic Party. There was actually very little chance that this lofty Princeton professor turned New Jersey political reformer would have ever been elected American president – except that Teddy Roosevelt's decision to run as a third-party candidate changed entirely the political landscape. As already noted, this action consequently split the large Republican Party electorate, and allowed Wilson to win the presidency with a simple plurality of the votes. But the election also brought large Democratic Party majorities in both houses of Congress, thus helping the new president get much of his legislative program moved forward. As president, Wilson stuck closely to his strongly Progressivist principles of low tariffs, taxes on the wealthy, and antitrust reforms in the banking and industrial world. He turned trust-busting from Congressional legislation to regulation by a new Federal Trade Commission, empowered to guard against the development of large trusts and monopolistic buyouts, which now were permitted only with federal approval. He moved quickly to reform the nation's erratic banking system (which suffered so easily from the panics that struck the nation at regular intervals) by setting up a Federal Reserve System to help expand or contract the nation's money supply in order to offset both inflations and deflations. By 1915 the new system was ready to go to work, just in time to help the nation face the troubles going on in Europe. But in the world of Black-White race relations he proved himself to still be a Southerner at heart, calling for the segregation of government workplaces and facilities, claiming that segregation removed the possibilities of racial tensions affecting government work (although both Roosevelt and Taft had undertaken something of a similar policy). His reelection in 1916 Coming up for reelection, Wilson campaigned on the basis of the many reform measures passed under his presidency (which seemed connected to an obvious prosperity the nation was experiencing at the time), and the fact that he had artfully kept the nation out of the war going on in Europe, one that was clearly grinding down civilized life on that continent. But events would soon change that picture. But that story belongs in the next chapter.

|

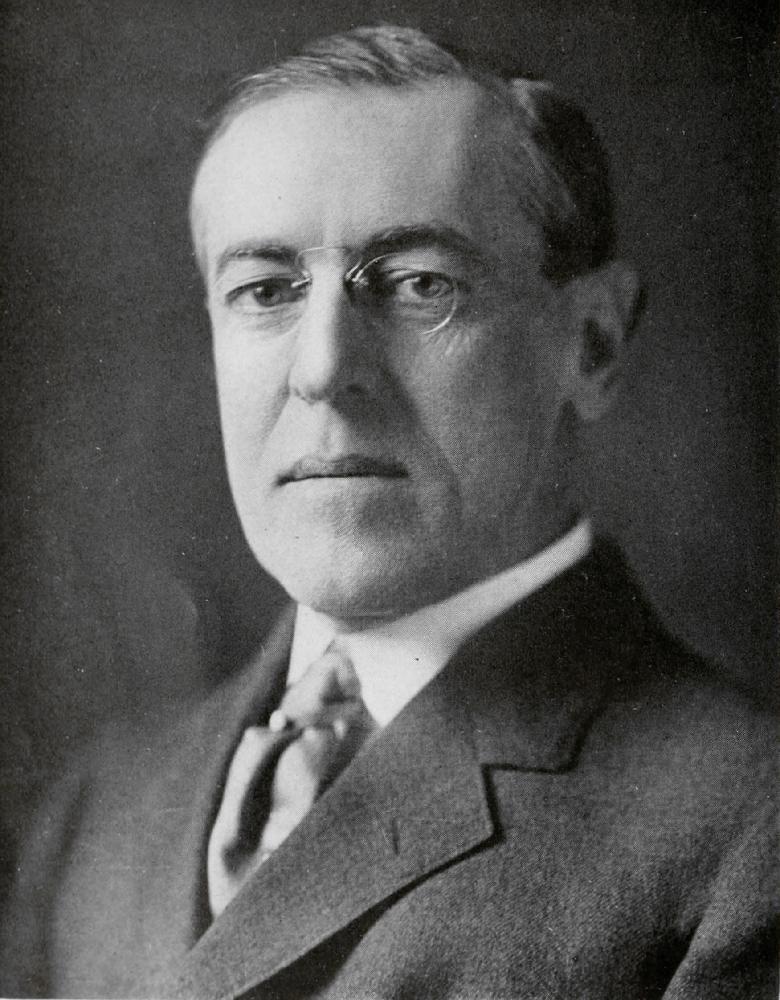

Woodrow Wilson (U.S. President

-1913-1921)

Princeton University professor

and president, New Jersey Governor, and ultimately U.S. President

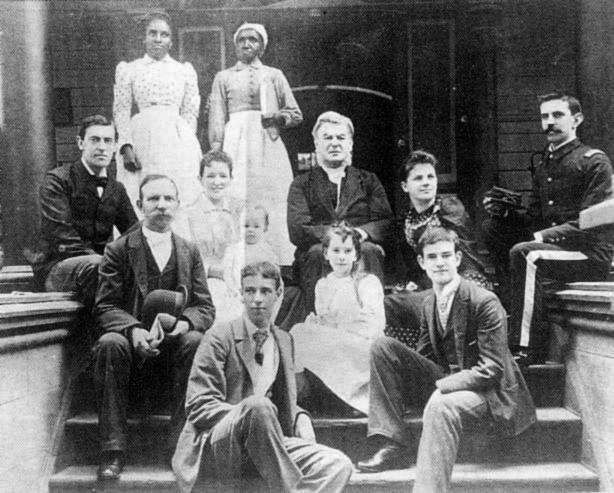

A young Thomas Woodrow Wilson

(left) and his family

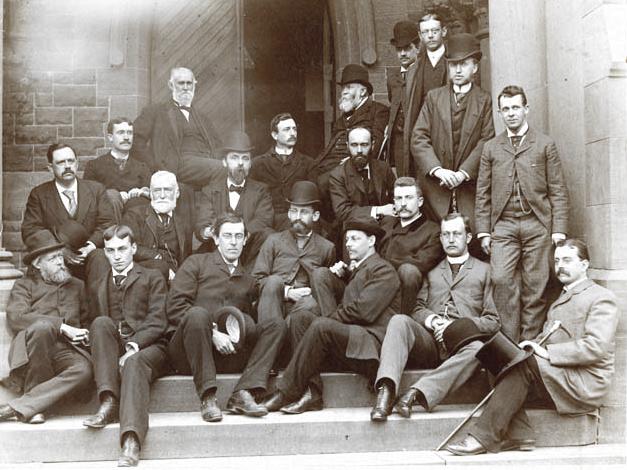

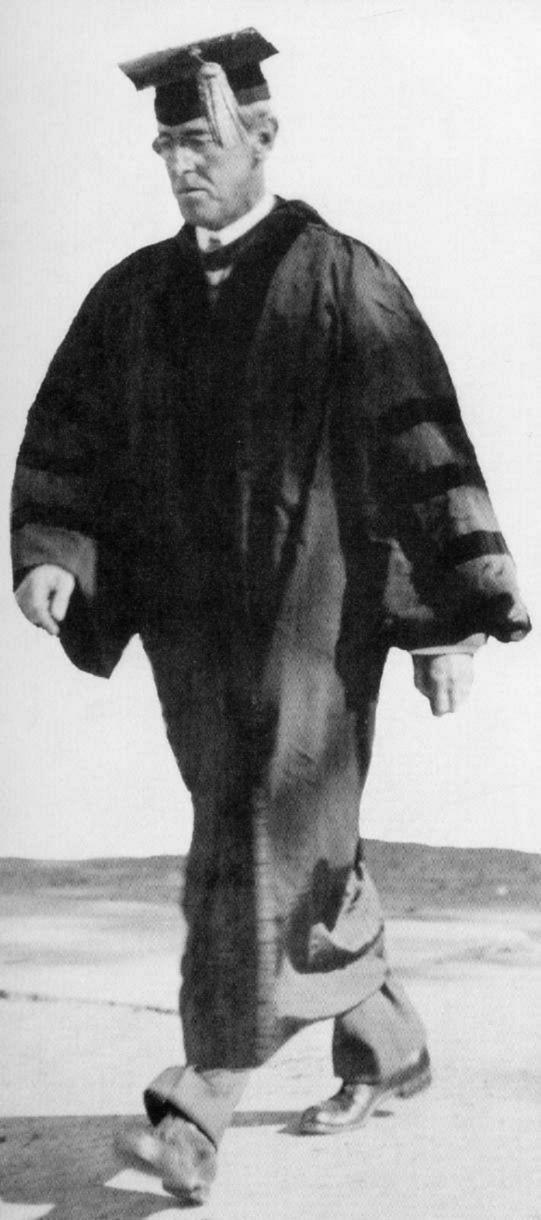

Woodrow Wilson (front – 3rd

from left) with Princeton faculty

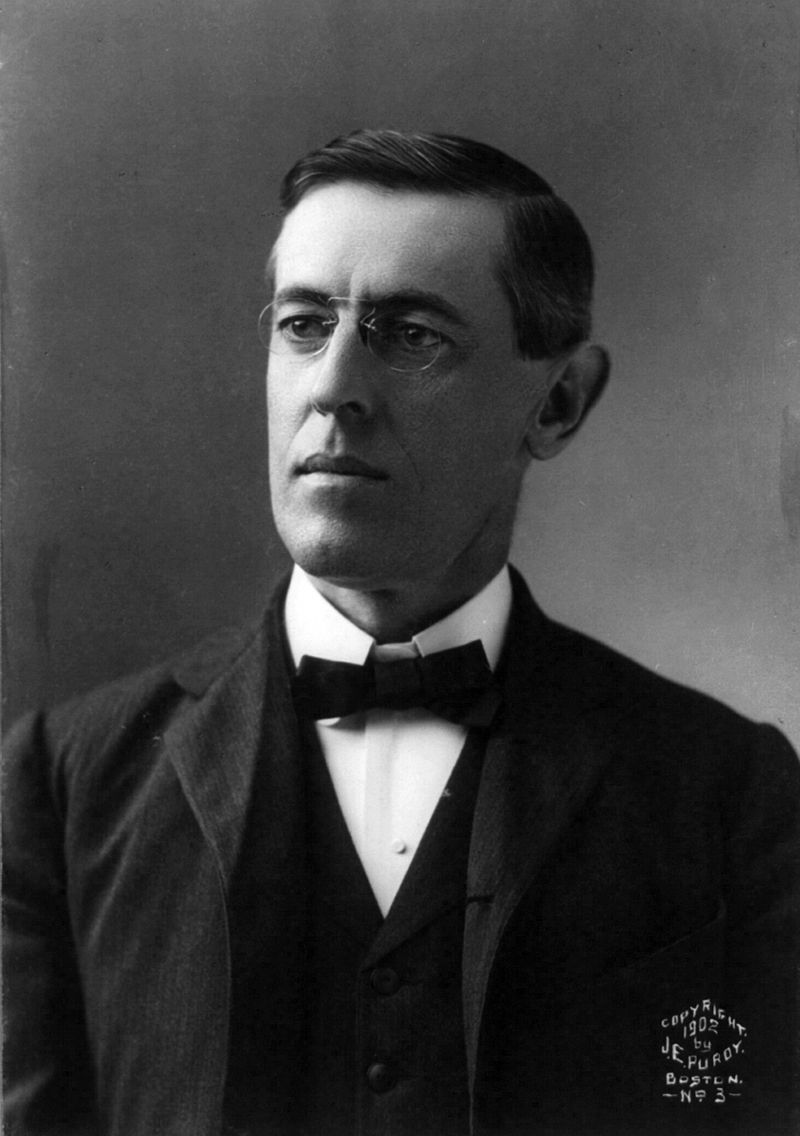

Woodrow Wilson as

President

of Princeton University – (1902-1910)

Wilson as New Jersey Governor

Woodrow Wilson, Governor

of New Jersey (1911-1913)

meeting at his mansion in

Sea Girt

Woodrow Wilson on the presidential campaign

trail

Wilson and Taft on Wilson's inauguration day (March 1913)

Wilson and his cabinet

Wilson and his family

(his wife of 29 years, Ellen

Louise Axson, died in August of 1914

while he was serving as US

President)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges