|

|

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

|

|

|

Liberalism as a rising worldview (cosmology) or religion At the same time that the concept of democracy was beginning to take hold of the American political imagination, a new term, "Liberalism," was also coming into vogue. The term was borrowed in part from the British Liberal Party which had recently switched its classical anti-state position into a very activist or Progressivist position in English political life. "Liberalism," as a political-social ideal (even ideology), crossed the Atlantic and began to substitute itself for the term "Progressivism" assigned to American political activism since the turn into the 20th century. Liberalism was a much more comprehensive idea than Progressivism. Progressivism had identified a number of programs that reformers sought to have instituted in order to bring the nation closer to utopian standards. Although Liberalism was also just such an idea and action, it was more than that ... much more than that. Like the term "democracy" (with which it identified itself closely) it was more a world-view ... a new understanding about life and how it was supposed to work. It was in fact (like its cousin "democracy") an ideology bordering on being a religion held in faith by a growing number of true believers. But whereas "democracy" tended to focus more on the idea of governmental reform, "Liberalism" took on for reform all aspects of social life – cultural, social, economic as well as political. In this it offered an even deeper challenge to the Christian world-view that had formed the ideological and spiritual foundation of America since its founding three centuries earlier. The instinctive goodness of man The Liberal ideology or cosmology (world view) was that man certainly knew the difference between right and wrong, and given the political power to do so, would correct the wrongs he saw in life – to bring about the right. Liberals, as Idealists, had little doubt about the basic goodness of man – if given the right opportunities. This was a key part of the Liberal doctrine which gathered support as the early 20th century developed. Recasting the idea of "religion"

To Liberals, religion1 was viewed as a private or personal matter – rather than as a vital instrument of social and political action. God was growing more distant – still lofty, but removed from the day to day affairs of man, which increasingly were seen as man’s jurisdiction. Liberalism was based on the ennobling of the idea of man – to the point of man being considered to be like God himself, the only significant sovereign over life on this planet (the heart of the Liberals' religion). Many Liberals (who also were Darwinists or Marxists) were in fact even acknowledged atheists (a religion without a personal god). "Sin" as environmental rather than

internal to

man As far as the problem of human sin, Liberals certainly recognized that there were sinners in the world. But they viewed these not as Christians did, as a matter of intrinsic sinful human nature manifesting itself ... but rather as the impact of environmental factors that undermined the noble human spirit. Hunger, poverty, disease, alcohol, illiteracy, and, most importantly, oppression by others who had indeed fallen into the grips of evil (usually considered the rich and powerful), were factors "external" to the spirit of common man. These external or environmental factors however could and should be corrected (by the reformers themselves) to bring about the conditions that would allow fully the human powers of goodness to manifest themselves. Thus democracy and Liberalism grew up together. Anything that would promote the dignity of man was considered democracy. Liberals looked forward eagerly to the day when common man would be freed from the shackles of antiquated social and cultural systems – to usher in a bright, new era of human wisdom, equality, prosperity and peace ... all summed up in the highly emotional word "democracy." "Democracy from above"

In this, Jefferson served as something of a patron saint to American Liberals, who a century earlier had expressed much the same expectations resulting from on-going and truly revolutionary social reform ... always directed from above by more enlightened individuals like himself. Indeed reform directed from above ... from above because the unwashed masses were not considered by Liberal reformers competent enough to figure out on their own the path to utopia – and although directed from above done in the name of "democracy" ... would always be one of the strange ironies of American Liberalism.2 Liberalism as a

rising Humanist

religion Liberalism was moving itself in America into an even stronger position as a rising religion, one entirely humanist or secular. At one point Liberalism – or ‘Humanism’ as it also called itself – did acknowledge itself to be a new religion (the 1933 Humanist Manifesto). But it would later step away from that confession (the 1973 Humanist Manifesto II)... because it discovered that by denying that it was a religion, but claiming for itself the status as mere Scientific Truth ... and by pointing out at the same time that Christianity in the public arena violated the Constitutional principle of the "separation of Church and State"3 ... it could force Christianity out of the public life of America and position its own "non-religion" of Liberalism (or Humanism) in Christianity’s former position as America's foundational cosmology or belief system, thus monopolizing American public life – intellectually, morally and spiritually (much as the Soviets did in Communist Russia). All that was needed to move history into this last, final Liberal (or Socialist) stage of man’s long development was a "revolutionary" push.

1Meaning "Christianity" – although a religious mix of Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism etc. was becoming increasingly popular among the cultural elite of the Western world. 2In continental Europe – this same philosophy was/is known as "Socialism." 3A "Constitutional principle" invented in 1802 by President Jefferson ... who was not even a participant at the 1787 Convention in Philadelphia that drew up the American Constitution. At that time of the Convention he was away in France ... and in general was not pleased with the Constitution in its original form anyway ... until 1800, when he himself became U.S. President under its provisions. |

|

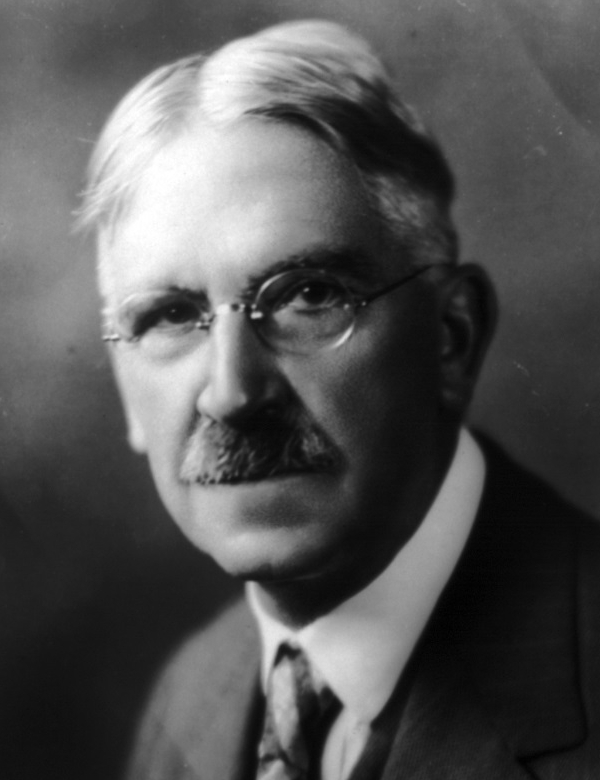

A major contributor to this Liberal sense of human confidence was John Dewey. This American

educator and philosopher truly believed in man’s natural ability

to

do the good and true if he were merely educated properly to these

higher standards. His optimism concerning human nature ultimately

had not only a tremendous impact on the way America looked at the

process of democratic education, it helped move America toward a

general Democratic Idealism that would eventually become the basis of

American Liberalism ... or Secular Humanism. A major contributor to this Liberal sense of human confidence was John Dewey. This American

educator and philosopher truly believed in man’s natural ability

to

do the good and true if he were merely educated properly to these

higher standards. His optimism concerning human nature ultimately

had not only a tremendous impact on the way America looked at the

process of democratic education, it helped move America toward a

general Democratic Idealism that would eventually become the basis of

American Liberalism ... or Secular Humanism.Dewey grew up in a typical middle class Vermont family in a largely unremarkable manner. He attended and graduated with distinction (Phi Beta Kappa) from the University of Vermont in the field of education ... and found a job teaching high school for two years in Pennsylvania and then a year closer to home at a primary school in Vermont. But he was not sufficiently challenged by the work and enrolled in a Ph.D. program at John Hopkins University in Baltimore. He then took a teaching job at the University of Michigan in 1884 ... and then ten years later moved on to Chicago to join the faculty of the new University of Chicago. This innovative Baptist school was set up with major Rockefeller funding designated for research ... also serving as the intellectual centerpiece for a number of affiliated colleges spread across the country. Here he often found himself working with children alongside Jane Addams, as the University was an important supporter of her Hull House. The rationalist atmosphere of the university fit well with Dewey’s growing secular rationalism ... labeled "Pragmatism" (or sometimes "Instrumentalism") as a rising philosophical movement. Here he undertook experiments in early education ... in accordance with his belief that early social education could produce (by way of the pragmatic example set by the excellent teacher) the type of rational adult that Dewey believed would usher in a brave new world of enlightenment. Ultimately however disagreements with the university’s directors caused him to resign in 1904, and take a position in New York City at Columbia University, where he would remain for the next quarter of a century (except for his two sabbatical years spent in China, 1919-1921) until his retirement in 1930. Here at Columbia he continued his experiments in early education and his publications in support of his educational theories (he published some 40 books and over 700 articles in his lifetime). His philosophy was standard Liberal theory (social environment determines human behavior; reform the environment in very practical ways and you will reform human behavior). He also, like so many intellectuals of his generation, believed that democracy was the proper formula for solving society’s problems (though critics were quick to point out that he never really explained how democracy was supposed to work in a mass society). He might not have stood out from the intellectual crowd, except that his massive number of publications made him a well-recognized leader in the rising Humanist movement underway in America. After his retirement from Columbia, Dewey continued over even the next twenty years to be very active in promoting his secular (even atheistic) humanist philosophy, taking a position in 1929 on the board of the Humanist Society of New York, then being one of the composers and signatories of the 1933 Humanist Manifesto, and an avid writer and lecturer on the subject thereafter. Perhaps also he more than anyone else was responsible for the split between the growing Liberal intellectualism of the country and its long-standing moral-spiritual foundation in the Christian faith. |

|

|

To Holmes, a society's foundational legal order was instead to be understood as an ever-developing foundation, a natural byproduct of constant social development or change. Constant changes in social circumstances by very necessity required even the most fundamental laws to be revised according to quite practical needs of the times, as these new social circumstances and thus social needs came into being. In other words, the law – even the most fundamental of all laws – ought to be whatever the political authorities should deem it to be by the sheer necessity of the times. And that held true especially of judges – who were given the critical responsibility of deciding what the rightful rules and conduct and the legal duties of all citizens should be … given the particular circumstances that the society faced at the time. Holmes termed his personal view of the law as "Legal Realism," sometimes also termed "Legal Positivism." As with all Progressivists, Holmes was certain that common sense – at least the "common sense" of those properly enlightened to the wiser ways of life – better served the needs of a constantly changing world. And certainly Holmes felt that he personally possessed all the right qualifications to understand and thus the wisdom to decide as to which were the more "realistic" lines and rules that a society should try to follow … and be judged by. Holmes was born of the right circumstances, his father (Holmes, Sr.) a well-known Boston writer and physician, with the family also close friends with the Transcendentalist Emerson and the famous writers Henry James, Jr. and his brother William James. Holmes followed in his father's footsteps to Harvard, where (like his father) he was a member of the Hasty Pudding writers' group and the prestigious Porcellian Club. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1861 … just in time to join the Massachusetts militia and become deeply involved in the Civil War … in the Peninsula Campaign, at Fredericksburg, the Wilderness, Antietam, and Chancellorsville, among other battles … being wounded on numerous occasions. Overall, the experience determined his view of how duty in service to society – in all its needs, but especially its most critical needs – required a careful marshalling by those given the responsibilities of social oversight (society's leaders). This understanding would become the basis of Holmes's Legal Realism. Not surprisingly, given his mindset, he chose to go into the practice of the law (Harvard Law School and then private practice in commercial and admiralty law), remaining a philosophical writer at the same time, in 1881 publishing a collection of his lectures and writings as The Common Law. It was here that the legal world would learn of Holmes's Legal Realism … underscoring how judges had to make decisions on the basis of numerous factors – in a way that made Legal Originalism "unpractical," even unserviceable. In 1902 Roosevelt appointed Holmes to the U.S. Supreme Court … where he got the opportunity to put his ideas to work. But here is where Legal Realism ran into some difficulties. Even Holmes contradicted himself as he moved from cases to cases over the years, his "realism" inclining him first in this direction and then later in an even opposing direction. Thus in his famous Schenck v. United States (1919) opinion he took a stronger line in defense of the state's rights to censor behavior than he had earlier in his dissent in the Baltzer v. United States (1918) case when he opposed the court in its conviction of an anti-war socialist who had been distributing pamphlets in violation of Wilson's Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918. In the Schenck case, Holmes came down strongly in support of state censorship, citing the state's rights in this famous comment that the First Amendment would not protect a person "falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic." But in that same year, in the Abrams v. United States (1919) case, Holmes now dissented from the view that the state had the right to persecute those demonstrating sympathies with the Russian Revolution then underway ... and who had opposed Wilson's decision to intervene in the subsequent Russian Civil War. So where exactly did Holmes stand with respect to the Espionage and Sedition Acts? That seemed to depend on whatever Holmes was inclined to find himself at the moment. In other words, under Legal Realism, the law was simply whatever the judges decided it to be … under merely the immediate circumstances. Thus the law was not really the law until the society was able to find out what the Supreme Court justices themselves felt about matters at the time. That's a lot of power … that answers to no one but the justices themselves.

|

|

| This

trend of American intellectuals to go down the road of Human Reason did

not mean that there was a widespread mood growing in America to get rid

of the idea of a God presiding over the nation, or Christ as the

designer of the moral-spiritual ideals guiding the nation. For most of

the people in the pews of the American churches, the personal

relationship with God that they held individually had not changed

substantially with all of this "higher" intellectual inquiry into the

nature and meaning of life. If anything, that relationship had deepened

as a result of the pain of going through a vicious Civil War. However, for the more intellectually inclined, the post-Civil-War era appeared as an age of wealth, security and leisure. For such Americans the idea of God did not seem to have a compelling place in the new, highly energetic, even highly competitive, social dynamic driving the country. Science and technology seemed to offer a better path to what faith once secured. In fact, science – not religion – was the key identifier that Humanists applied to this rising Secular Liberal-Democratic faith. Science worked rationally, openly, no miracles, just hard work with predictable results. This seemed to be a vastly better way of going at life than expecting some peculiar intervention from a world beyond to clear away life's hurdles. And as science was clearly leading the country to unprecedented human progress, in the lives of the more intellectually inclined, Christianity simply seemed to shift to the sidelines. A rising question of the reliability or "inerrancy" of Biblical Scripture

Ultimately, the Liberal challenge once again raised the age-old question (since at least the late 1600s) of the reliability of Scripture as foundational Truth. Stories that seemed to contradict what science, or just modern common sense, would dictate came again under attack by the more enlightened minds. But Scripture was the bedrock of American Protestantism. Scripture was the final arbiter on what was Absolutely True and what was just merely human Rationalism. It was the foundation of all that Christian Americans held as moral absolutes. And ultimately, to Christians, it defined the very purpose of human life itself. Liberals, whose faith was built now on the bedrock of secular science, naturally raised questions (and sneers) about Scripture’s tales of changing water into wine, walking on water, raising the dead, stopping the sun in its path, etc. Biblical miracle stories and the rules of science clashed terribly, forcing Americans to choose on which side of the rising controversy they stood: for the Bible of God, Christ, and the Church – or for Science (and 20th century commonsense). Defenders of the faith

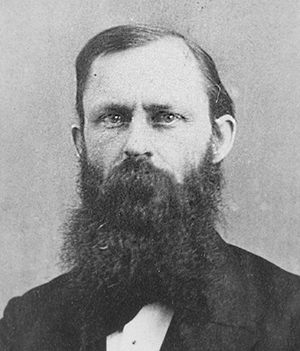

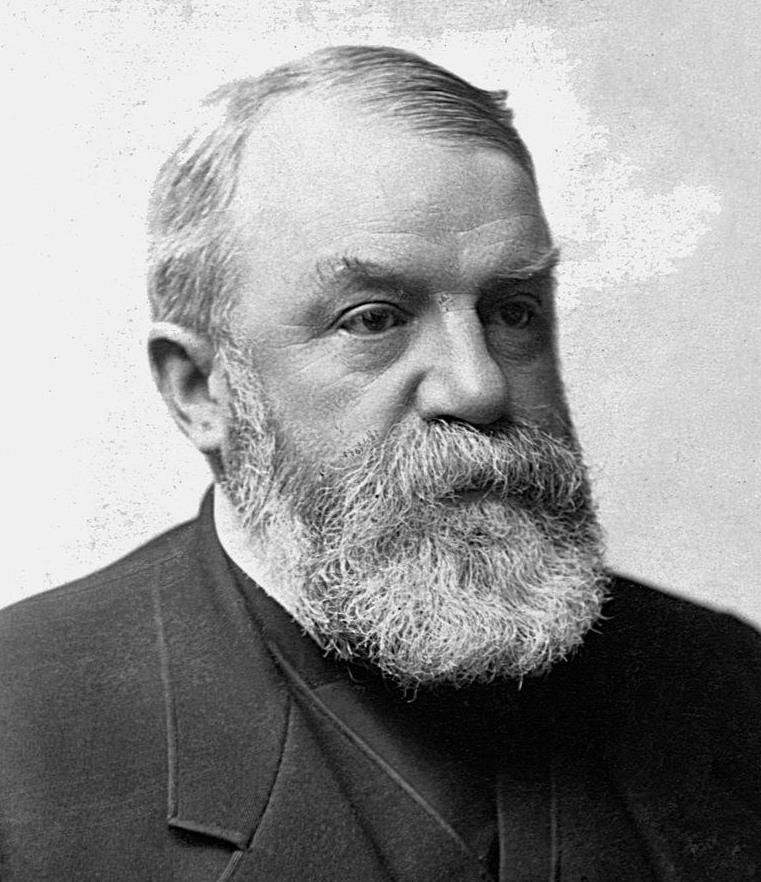

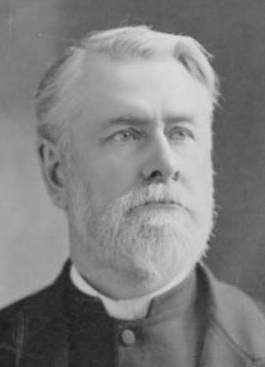

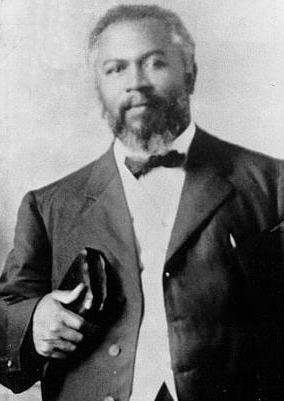

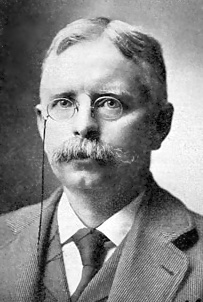

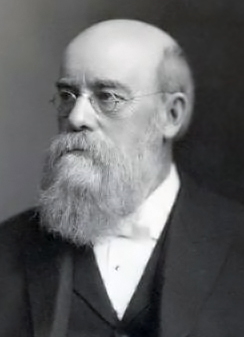

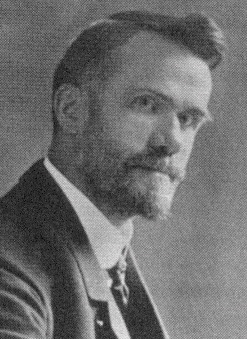

But such attacks on Biblical faith did not occur without defenders of that faith trying to halt or even reverse this development. Given the serious challenge that the rising faith in science made to the old faith in God and Christ, some Christian apologetics (written and spoken defenses of the faith) tried to take on some of the new ideas and attitudes to create a more comfortable fit between the old faith and the rising world of modern science. But these ideas, however, would trouble the Christian community itself deeply. These new ideas and attitudes were not just a matter of new style versus old style – like the earlier battles (during America's Christian Awakenings) between the New Lights and the Old Lights concerning the spectacle of outdoor revival campaigns. Even during the days of the Civil War, Darwin's challenge to the idea of life's divine origins as described in the Bible was finding a strong response in numerous Christian circles. One very notable individual in this regard was Charles Hodge, the dominant personality at the Presbyterian seminary in Princeton all the way up to 1878. He proudly boasted that he had held the line firmly against the kind of theological innovation that was infecting fellow seminarians elsewhere. Others responded simply by taking some kind of middle road between Christian traditionalism and rising Christian Liberalism. One of these was Crawford H. Toy, a professor at the Southern Baptist Seminary, who won hearts by simply focusing on the spirit of love that stood at the heart of Christianity – rather than theological doctrine. Unfortunately even that proved to be too much of a compromise for the otherwise creedless Baptists, whose Convention in 1879 forced him to resign his position at the seminary.   Hodge Toy More successful in advocating a "middling" approach was Henry Ward Beecher,107 son of the conservative Presbyterian preacher Lyman Beecher and brother of fellow Abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom's Cabin). As a popular pastor and circuit preacher, Beecher sidestepped the controversial intellectual issues of evolution and Biblical reliability, even stating at one point that he saw no problem with the theory of evolution – as long as it understood God to be at the heart of the process. He preached a very upbeat message of love, and a willing accommodation to the changing industrial culture developed around the Christian community. And he proved to be quite successful in developing a stable Middle-Class message in the face of Darwinism's intellectual challenge, all the way up until his death in 1887.   Beecher Moody Charles Briggs and Biblical "higher criticism"

Yet

while a number of preachers were trying to find some kind of a middle

road for the "average" Christian to go down, the battle at the higher

realm of Christian intellectualism only hardened. A major contributor

to his hardening was Union Theological Seminary's professor Charles

Briggs. He even succeeded in getting himself excommunicated from the

Presbyterian denomination in 18934

because of his teachings that text-criticism or literary analysis amply

proved among other things that Moses did not actually write the first

five books of Scripture but that these writings were the result of the

much later collection of at least four different narrative traditions,

and that Isaiah did not write the entire work given under his name but

that later disciples of the Isaiah school had written the second half

of the work. Although for any who might have understood that the Jewish

Scriptures were community narrative (not "science"), such a revelation

should have come as no surprise. Biblical narrative was about finding

the path to Truth through divine inspiration, and was not assembled

anciently by those with a modern scientific worldview. Yet

while a number of preachers were trying to find some kind of a middle

road for the "average" Christian to go down, the battle at the higher

realm of Christian intellectualism only hardened. A major contributor

to his hardening was Union Theological Seminary's professor Charles

Briggs. He even succeeded in getting himself excommunicated from the

Presbyterian denomination in 18934

because of his teachings that text-criticism or literary analysis amply

proved among other things that Moses did not actually write the first

five books of Scripture but that these writings were the result of the

much later collection of at least four different narrative traditions,

and that Isaiah did not write the entire work given under his name but

that later disciples of the Isaiah school had written the second half

of the work. Although for any who might have understood that the Jewish

Scriptures were community narrative (not "science"), such a revelation

should have come as no surprise. Biblical narrative was about finding

the path to Truth through divine inspiration, and was not assembled

anciently by those with a modern scientific worldview.But Briggs went further, even claiming that the Old Testament was morally inferior to the moral development of modern times. This so enraged the Presbyterian denomination that it not only excommunicated him but moved to block Briggs' professorial appointment to the faculty of the Union Seminary in New York City. But the seminary refused to dismiss Briggs, and instead the seminary withdrew from the Presbyterian denomination. Azusa Street Pentecostalism

Then,

while all of this intellectual warfare was going on within the higher

reaches of Christian leadership, a strange revival (but all revivals

start out as strange events!) which exploded at the beginning of the

20th century across the Atlantic in Wales, deeply transforming Welsh

society, made its way to America – thanks to a number of Holiness

evangelists who brought the event to American shores. It dug in deeply

in California in early 1906 when strange physical healings and

"speaking in tongues" broke out at a home – when guest speaker William J. Seymour

was kicked out of church after bringing his Pentecostal message there,

and simply moved his activities to this home. The event soon drew

crowds to witness and then participate in this strange behavior, until

it became literally an on-going twenty-four- hour- a-day phenomenon.

When the crowds collapsed the porch to the house, the revival moved its

operations to a Black Apostolic Faith Mission building on Azusa Street,

making it quite inter-racial in nature as well as inter-ethnic

(Hispanics also attending), even bringing women forward to take leading

roles in the revival. Hundreds, then over a thousand individuals would

soon be attending the meetings. Then,

while all of this intellectual warfare was going on within the higher

reaches of Christian leadership, a strange revival (but all revivals

start out as strange events!) which exploded at the beginning of the

20th century across the Atlantic in Wales, deeply transforming Welsh

society, made its way to America – thanks to a number of Holiness

evangelists who brought the event to American shores. It dug in deeply

in California in early 1906 when strange physical healings and

"speaking in tongues" broke out at a home – when guest speaker William J. Seymour

was kicked out of church after bringing his Pentecostal message there,

and simply moved his activities to this home. The event soon drew

crowds to witness and then participate in this strange behavior, until

it became literally an on-going twenty-four- hour- a-day phenomenon.

When the crowds collapsed the porch to the house, the revival moved its

operations to a Black Apostolic Faith Mission building on Azusa Street,

making it quite inter-racial in nature as well as inter-ethnic

(Hispanics also attending), even bringing women forward to take leading

roles in the revival. Hundreds, then over a thousand individuals would

soon be attending the meetings.Thus pentecostalism or the Charismatic Movement came to America. But eventually the Azusa Street Revival would burn itself out, although it would leave behind rather permanently a strong spiritual legacy – occasionally picked up again here and there in 20th century America. Most notable was the large Assemblies of God Christian denomination formed in 1914 out of the Azusa Street Revival. The Assemblies of God or AG Church would continue to develop pentecostalism or the charismatic movement all way to the point today in which the denomination has around 370 thousand congregations with over seventy million members worldwide. The Social Gospel

At the same time, Christian Liberals busied themselves trying to find, through their Social Gospel, a middle ground in the science-versus-Christianity controversy, explaining that fact and faith were two different things. Science dealt with fact. But faith dealt with the question about how you handled fact. Christianity was ultimately what you did with your life, the moral quality of the decisions you made, especially in the social context of family, community, nation and even the world. Key voices in this approach to Christianity were the economist and founder of the American Economic Association and also founder and secretary of the Christian Social Union, Richard Ely; the Congregational pastor, writer and ardent social reformer Washington Gladden (considered the Father of the Social Gospel Movement of the late 1800s/early 1900s); and Baptist pastor and seminary professor, Walter Rauschenbusch. All three of these men were very active in their support of Progressivist economic programming, designed to help lift the American working class out of poverty – a very noble enterprise.    Ely Gladden Rauschenbusch

But all of this fine work had little to do with personal salvation, the individual "born-again" experience that comes with stepping back from the world and its ways in order to embrace a more personal relationship with God. Rauschenbusch was in fact very dismissive of such an approach to Christianity, seeing the true sin that needed to be addressed by the Christian as that of society and its cruelties. In short, Christian Liberalism, with its Social Gospel, was largely a matter of high social morality, the value of which one did not need to be a Christian to appreciate. Indeed, as Liberal America opened itself to the larger world around it, it encountered Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, all of which had different ideas about the place of God in nature, but all of which held pretty much the same moral views on social behavior. Universalism

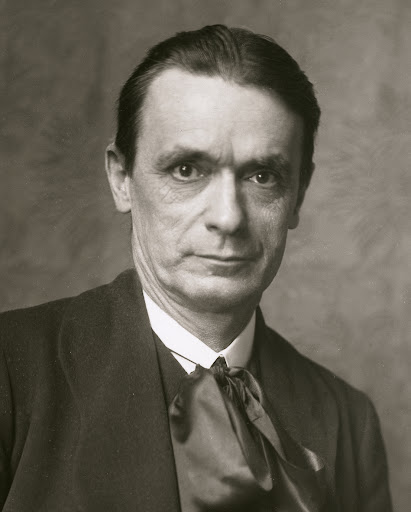

Indeed, a number of intellectuals even proposed simply to create some kind of universal religion, combining the moral features of Christianity, Buddhism, etc. Theosophy was just such an example – cultivated outside America by such Humanists as the Russian occultist and author Helena Blavatsky, her British disciple Annie Besant, and the Austrian educator Rudolf Steiner – that was taken up in America by intellectuals seeking to combine science and the mysticism of the world's great religions, as a form of personal development (also very popular later in the 20th century among very self-focused American hippies!). Thus science could continue to pursue fact and Progressive Liberals could pursue through private faith some kind of universal moral code, even some kind of personal mysticism.    Blavatsky Besant Steiner Humanism

All of this of course was simply another version of the age-old philosophy of Humanism (the self-sufficient enlightened individual) – pursued at various times in history with mixed results. It was idealized during the Renaissance, leading eventually to the corruption and ultimately splintering of the medieval Church, and then after that the rise of fully sovereign monarchs pursuing greedily their own dynastic fortunes, which produced exhausting wars that accomplished nothing, until another attempt to humanize a bankrupt monarchy in France brought forth a very violent Revolution, and subsequently the bullying Napoleonic Empire required to save France from its self-destructive ways (by focusing those destructive instincts abroad). On and on it went – from one age to the next, enlightened man about to bring the world to utopia through clever human design and effort – ending up instead destroying huge sections of that world. But at the time, these memories had faded from the minds of America's (and Europe's) rising group of Humanists, who as they stepped into the 20th century were unaware of how close they were coming, in the name of idealistic nationalism (and in America, its democratic Idealism), to the huge moral accounting known as the "Great War" (World War One: 1914-1918). 4Commentators have noted that part of his difficulty with the denomination occurred in part also because of his abrasive manner when challenged. |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges