|

|

War clouds begin to gather in

Europe War clouds begin to gather in

Europe War finally breaks out War finally breaks out

1914: A

bloody stalemate quickly sets in 1914: A

bloody stalemate quickly sets in 1915/1916:

The extremely ugly war

seems to have no end in sight 1915/1916:

The extremely ugly war

seems to have no end in sight Revolution in Russia

(1917) Revolution in Russia

(1917) Wilson (at

first) keeps America

neutral Wilson (at

first) keeps America

neutral The

Americans

finally

enter the War The

Americans

finally

enter the War

America

is fully mobilized America

is fully mobilized

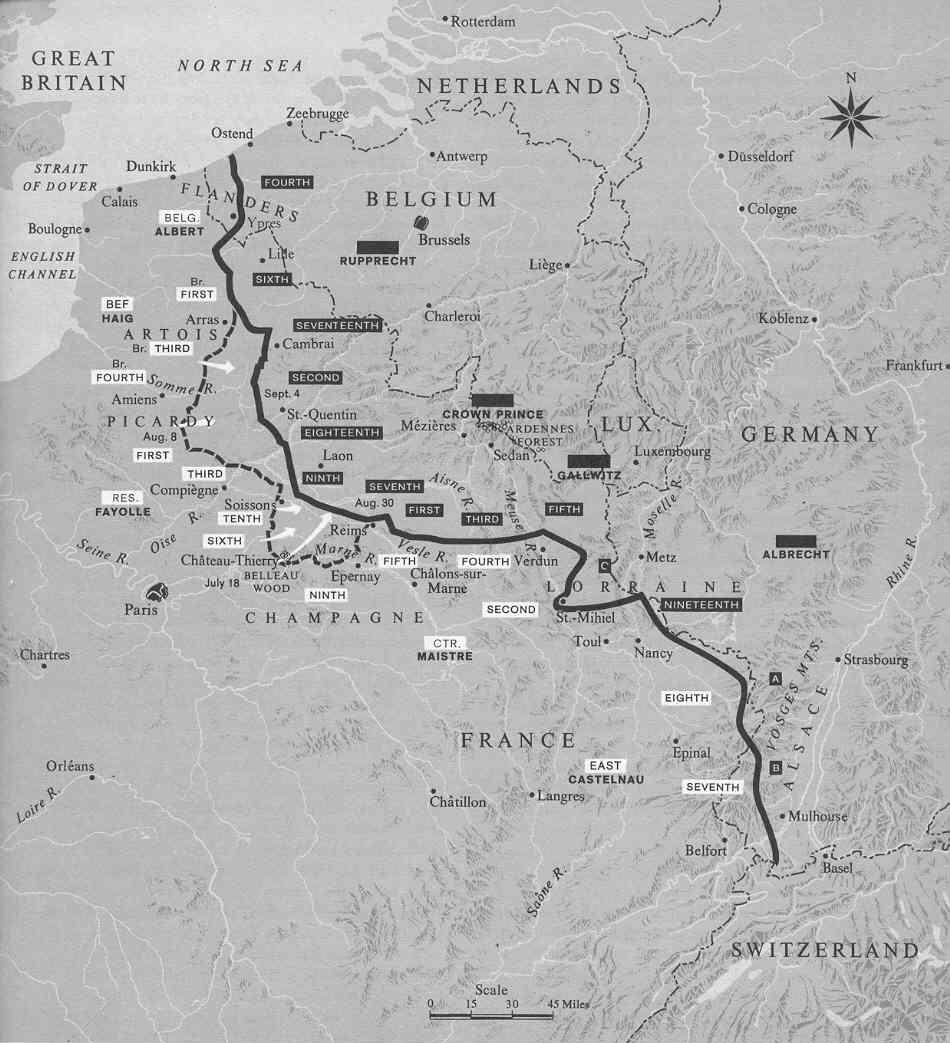

Wilson announces his "Fourteen Points" for world peace Wilson announces his "Fourteen Points" for world peace The German begin to fall back – summer of 1918 The German begin to fall back – summer of 1918

The

Germans are forced into deep retreat – September – November 1918 The

Germans are forced into deep retreat – September – November 1918

The

air war The

air war

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 452-470. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

The mounting dangers of nationalist diplomacy

The royalty and aristocracy (and their upper-middle-class associates) of Europe had long treated wars and diplomacy as a private or personal game of the members of their class. This was a most amazing class – with a good number of the European royalty in the early years of the 20th century being direct descendants of Queen Victoria of England and thus being first cousins, as for instance her grandsons English King George, German Emperor Wilhelm, and Russian Tsar Nicholas! Wars and diplomacy were considered the private business of their class alone. Involving the masses of peasants, townsmen and industrial workers in this game was considered inappropriate – even highly dangerous – as the Napoleonic Wars at the beginning of the 1800s had clearly demonstrated. Armies and envoys were understood to be the tools of the ruling classes, to be used solely to promote the interests of the reigning kings and emperors and their personal dynasties. But the rising spirit of nationalism was drawing the "democratic" masses into this game – clearly enhancing the powers of the ruling class players, but also drawing the European heads of state forward toward a conflict that they would soon discover was beyond their ability to manage or control. The passions of a fully armed society (and not just the ruling class and its private armies) once mobilized would move in the direction that tribal passion – and not diplomatic good sense – would take the nations of Europe. Germany’s new Emperor Wilhelm was becoming an increasing source of concern to the other players. Wilhelm demanded a greater share in the imperialist game than had previously been allotted to Germany. Also, despite the efforts at the Berlin conferences by European envoys to put some order to the redistribution in Southeastern Europe of pieces of the crumbling Turkish or Ottoman Empire, the Balkan peninsula continued to offer dangerous opportunities for trouble. The land-locked Austrian-Hungarian Empire had been looking for expansion into that area (and the possibility of finally acquiring a place to plant a naval base of its own on the Adriatic and thus the Mediterranean Sea), as had been its chief competitor in that region, Russia (for roughly the same reasons) – but also Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia. This potential for growing conflict among these interested powers drew the other European players (Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, etc.) into the Balkan game as well – and soon formal alliances were drawn up to buttress the interests of one side or the other. Thus by the early 1900s, the unifying ideal of the Concert of Europe had been replaced by a deeply divided Europe. On the one side of this division were the powers of the Triple Entente: Britain, France and Russia. This alliance was formed to check the growth of another new alliance, that of the Central Powers: the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires and, for a while anyway, Italy. The first Moroccan crisis (1905-1906)

Wilhelm was very unhappy about Germany's lack of a grand overseas empire such as the French and British possessed. He felt that it was in part the result of a conspiracy of the French and British to keep Germany from its place in the sun. He resented especially deeply the 1904 agreement by which France recognized Britain's dominance in Egypt in exchange for Britain's recognition of French dominance in Morocco (supported by Italy and Spain). Germany had been part of the 1881 agreement on Morocco, but had not been included in this new agreement. Wilhelm fumed. Thus in 1905 Wilhelm sailed to Morocco to meet with the Moroccan sultan and offer German protection in defense of Moroccan sovereignty. A huge diplomatic crisis thus resulted. To avoid a mounting confrontation, all parties finally agreed to a conference to be held the following year. The conference confirmed the sovereignty of Morocco, but in fact allowed for both Spain and France (not Germany) to serve as the "protectors" of that sovereignty. Germany was still excluded from a role there. Bosnia-Herzegovina (1908)

Then with no warning, Austria-Hungary simply annexed the Balkan territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina (part of the weakening Turkish Empire), infuriating the Serbs who had a huge interest in the same region as an addition to their Greater Serbia, and as a path of access to the sea (Serbia also was landlocked). Serbs burned with a deep bitterness against the Austrians over this land grab. But this land grab also widened the divide between Austria and Russia, the latter being a strong supporter of Serbia. It also caused some consternation with Austria’s ally Germany, which had not been consulted prior to the event. And it forced France and Britain – both neither in a position to help Serbia nor willing yet to help Russia – to stand off, very unhappy over the event. Turkey however seemed content to receive monetary compensation for its loss of another two of its provinces. But in general, feelings were running very raw in Europe’s capitals. The second Moroccan crisis (1911)

Morocco was not doing well under French and Spanish protection. The sultan’s finances were in crisis mode and unrest among the Moroccans was building. The French decided to send French troops into Morocco "to protect the lives of foreigners," upsetting greatly Wilhelm who saw this as simply a ploy for the French to add Morocco to their North African empire. He countered the French move by sending a German gunboat to Morocco to protect German citizens, and another crisis erupted. But France (and Britain, backing France) refused to be intimidated. Wilhelm backed down. War fever refused to cool down however. Nationalists of all the major European countries seemed to want a street fight of some kind to finally settle the matter of Europe's power alignment. But what they failed to realize was that such a fight was not destined to be merely an afternoon sporting event. The powers seemed so evenly balanced at this point that once underway such a conflict would simply stalemate itself into a long, unrelenting slaughter – the kind that could result only in a huge loss of political strength by all parties, the kind that would in the end (should there ever be an end) resolve nothing. But passions at this point had greatly overridden cool logic. A war now seemed inevitable.

|

|

|

The assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand (June 28, 1914). The absorption of Bosnia-Herzegovina by Austria was by no means a finished matter. Serbia was in no mood to accept this development and Austria knew it had work to do to complete the absorption of these Balkan provinces. When in June it was announced that the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand – acting on behalf of his eighty-four-year-old uncle, the Emperor Franz Joseph – would be visiting Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, Serbian nationalists (including even some members of the Serbian government) planned his assassination. They wished to disrupt Austria’s plan to create a new Triple-Monarchy (Austria, Hungary and now also a Slavonic state) under the Austrian emperor’s authority. Austria’s plan would have ended the Serbian dream of an independent Greater Serbia. Somehow Austria needed to be stopped.

|

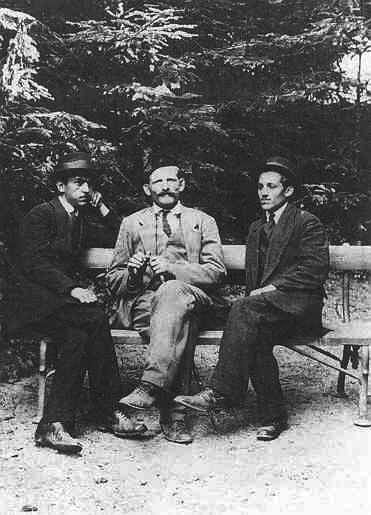

The

Austro-Hungarian Emperor

Franz-Josef followed by the Archduke Franz-Ferdinand

Gavrilo Princip (on right) and fellow Serbian nationalist conspirators

Austrian

Archduke Francis

Ferdinand and his wife Sophie just before their

assassination

|

Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia

Tragically, despite a number of blunders, the assassination succeeded, throwing Europe into diplomatic chaos. At this point Austria wanted to destroy Serbia, but needed German backing. Wilhelm was reluctant to get involved in such a tangle but also knew that German support was vital in keeping the Austrian-Hungarian empire from falling apart. He had to support Austria. Aware of this backing, the Austrian cabinet placed extremely heavy demands on Serbia to allow Austria to take over the search in Serbia for the Serbian criminals – presuming a Serbian refusal, and thus in effect precipitating the war sought by Austria. Surprisingly most of the demands were agreed on by the Serbian authorities. But Austria insisted that not most – but all – of the demands be met by Serbia. When Serbia stalled, Austria felt it had the justification it needed and on July 28 declared war on Serbia. Austria supposed that this would remain a quick, local war, as most of the wars in the Balkans had been. But Austria foolishly had failed to take note of the fact that things were very different in the European diplomatic world at this point. Russia joins in

It was now Russia's turn to decide what to do. Russia was not only the protector of Serbia, it saw in this outbreak of war the opportunity to take advantage of the crisis to seize Constantinople and complete its dream of possessing its own port with direct access to the Mediterranean. But Russia was not really prepared for a major war – and Tsar Nicholas was well aware of this fact. Yet he could not hold back his own ministers who wanted war nonetheless. They demanded a general mobilization. Nicholas knew well that this would constitute a declaration of war against Austria, and that by the terms of the Dual Alliance this would automatically bring Germany into the war as well. But he finally gave in to his ministers. On July 29 the Russian cabinet called for mobilization. A few hours later he received a conciliatory letter from his German cousin Wilhelm. But it was too late to call off the mobilization. Russia was at war. Germany and France join in

Germany reacted immediately to the news

of the Russian mobilization with a demand that the Russians immediately

back down, and declared war (August 1) on Russia when Russia failed to

do so. Germany then sent a letter to France demanding to know whether

or not France was intending to stay out of the conflict, received an

ambiguous reply, and thus most unwisely declared war on France (August

3).

|

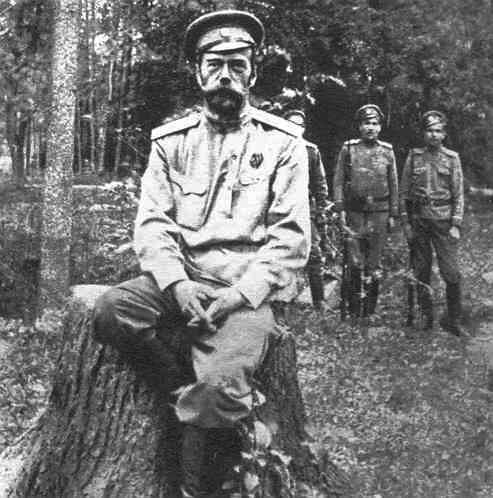

Russian Czar Nicholas

II and

the

Grand Duke Nicholas

|

The German invasion of Belgium, and Britain's entry into the war

Following an older plan laid out by General Von Schlieffen back in the late 1800s – a strategy that worked well for the Germans when they quickly crushed France during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 – the German intent was to immediately march on France and quickly seize Paris, leaving the French largely unable to remain in the conflict that was fast unfolding. But to do so German troops would have to pass through Belgium, whose steadfast neutrality during any European conflict had been guaranteed by treaty not only by Britain and France – but also by Germany. Thus Germany sent a request to Belgium (August 2) for permission to pass through the country in order to attack France. But Belgium refused permission. On August 4th, Germany crossed the border into Belgium anyway. This then led Britain to declare war on Germany for having broken the neutrality treaty. Britain claimed to be acting to protect that guarantee (and its ally France). Italy, however, refused to support its allies Germany and Austria, claiming that it had agreed to support them only in a defensive war, not a war of aggression. Italy thus at this point remained neutral.

|

Berliners

"off to

Paris" – 1914

Englishmen

lining up to join

the British military

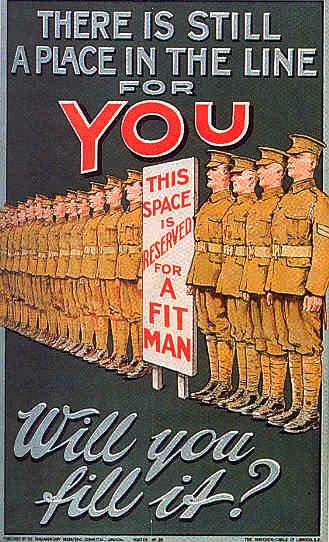

British

War

Poster

Wartime allies: French General

Joffre, French President Poincare, British King George

V,

French General

Foch, and

British General Haig

|

Turkey joins the German-Austrian side

After some indecision on the matter (the British had, after all, been supporters of the Turks in their troubles with the Russians and the Austrians) the Turks, impressed by German military professionalism, decided to come into the war on the side of Germany. Whether or not this would add much to the joint German-Austrian effort was at this point somewhat debatable. But in any case, it put Turkey squarely into the war.

|

|

|

In the first month (August) of this long-developing war, things took pretty much the shape in Belgium and France that it would maintain for the next four years. The Germans had expected to swing through a relatively defenseless Belgium and descend directly on Paris before the French could get organized. Without Paris, France was defenseless. Thus the march through Belgium – which Germany expected would bring a hostile British response. But the action was supposed to be so swift that, by the time the British got moving in defense of Belgium, and France also got itself mobilized, Paris would be in the hands of Germany and the war effectively would be over. But Germany was not expecting such stiff resistance from the Belgians, which slowed the surprise move down greatly. The Germans were furious at the audacity of the Belgians and poured their wrath out onto the population of this small country, civilians included. So savage was the behavior of the Germans that the label "Huns" came to mind to those watching the German action. This would later come to haunt greatly the German national image. Also, Britain was indeed able to get some of its small army (the British Expeditionary Force or BEF as it would be termed during the war) in place in Belgium, at least sufficient in number to help slow down the momentum. And France frantically mobilized whatever resources it could, and though being forced to fall back in the face of the much better prepared German army, was able to slow down and then grind to a halt the German offensive, just north of the Paris suburbs. This halting of the German offensive was much the same along a line that curved eastward and then north through northern France, from the Rhine River in the East to the Belgian border (and into Western Belgium) along the North Sea in the West. Here a well dug-in battle line would hold rather permanently, barely moving but a few miles back and forth from its original position laid out in the first month of the war, despite four years of ferocious assault and counter assault. Millions of men would be sacrificed in the process, all without any seeming effect in breaking the murderous stalemate that settled in along this long line of battle.

|

Belgian Cavalry to the front

Ancient Louvain, destroyed

by the Germans in retaliation for civilian resistance

to the German occupation

Germans

moving through Place

Rogier in Brussels

French troops pass Versailles Palace on their way to the War – August 1914

Destruction of Rheims, France,

by German bombardment – beginning on September 18,

1914

Arras after

German artillery

bombardment

German dead

at the Marne – 1914

More

Frenchmen to the front – October 1914

200,000

French

soldiers died

in the first month of the war alone.

By October, 2 months later,

the glamor of war is gone.

The peasants don't even

look up from their work as the soldiers go by.

|

The Eastern Front

Another long but more changeable line of battle ran through Eastern Europe from the Baltic Sea in the North to the Balkan Mountains of Serbia in the South. Russia and Germany were engaged against each other in the north, Russia and Austria in the middle portions of the line and Serbia and Austria in the south. Russia had a huge (but ill-equipped and poorly trained) army to throw at Germany – and chose to initiate the action. However, Russia’s attack failed, despite Germany’s initial focus on the war in the West with France. Worse, Russia immediately found itself in trouble when one of its large field armies was skillfully surrounded and forced to surrender to the Germans. Russia still had more men to bring into the war. But this initial defeat would be merely the beginning of many troubles the Russians would experience in continuing a war they now had no idea of how to pull out of without a huge loss of national pride. In the central part of the line of engagement, the Russians were facing an Austrian army of equally inferior quality, largely because of the latter's multinational character. Here the war bogged down along a line that reached from the Carpathian Mountains in the south to Silesia in the north, and efforts of both sides to move the line proved to be dismal failures. In the south, Russia’s Serbian allies were able, for the time being, to hold back the Austrians. But they had much smaller resources at their command and thus time was not on their side.

|

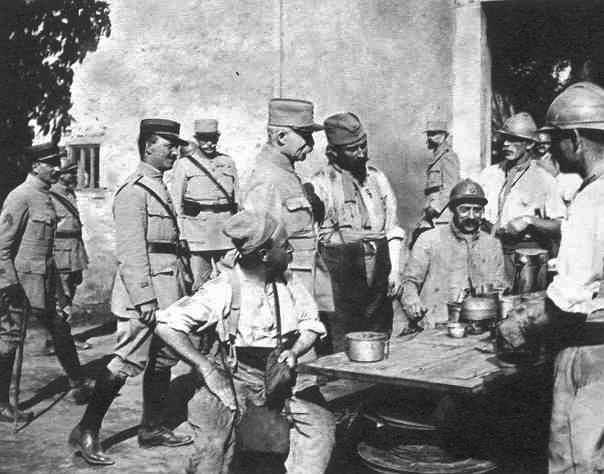

Cossacks on the

attack

Serbian troops moving up to the front against the Austro-Hungarians

Austrian

troops executing

Serbian POWs

|

|

As Christmas 1914 came and went, so with it went the idea that the war would be "over by Christmas." Along the entire Western Front soldiers had dug deep trenches and settled into a life of moving back and forth between the rear and forward trenches, going into action, and then falling back to recover (whatever was left of a unit anyway) in the rear. The routine never varied. At the front the soldiers awaited the pounding of the enemy lines by heavy artillery before being ordered up out of the trenches in order to cross thick lines of barbed wire and a no-man's land filled with shell holes and dead and decaying bodies – facing enemy rifle and machine gun fire as they went – until the remaining soldiers were ordered to retreat after having failed to dislodge the enemy from their trenches. On and on it went. The Germans got the brilliant idea of introducing poisonous gas with the hope of clearing the enemy trenches before their assaults. But while this proved deadly it did not prove as effective as they had hoped in clearing the enemy lines, and soon the British and French were attempting the same tactic, now also employing gas masks to protect themselves in the process. Between the gas attacks and the constant barrage by enemy artillery, life on the front was a person's worst nightmare, one that refused to go away. There was no escaping the slaughter. The casualty lists soon numbered in the millions on both sides. Other countries join in

It seems strange that with the horrifying experience of the Great War (as it was coming to be called) by this point a year old, any other countries would want to get involved. But political folly is not unknown in high political places. For Bulgaria there was in fact a good reason for joining the war: to get back the lands that it had lost to Serbia and Greece in the Balkan wars. In this they largely succeeded – until the war turned against their German allies in 1918. Italy, however, was another story. Italians were deeply divided about the war. In one of the many secret treaties being issued during the war, the British and French in April of 1915 promised the Italian government lands taken from Austria along the upper Adriatic Sea coast and along the southern slopes of the Alps, plus the possibility of picking up colonial territory from the Germans in Africa. And although many Italians were adamantly opposed to getting involved in the war for any reason, pro-war enthusiasts, led especially by the fiery D'Annunzio, finally got most of Italy worked up for war. Finally in May, Italy declared war, coming in on the side of the British and French against Italy's former allies Germany and Austria. Not all Italians would be happy about this. Italy was really not prepared mentally or physically for such a war. As it turned out, the Italians were unable to dislodge the Austrians from the mountainous Italian province of Trentino, despite repeated efforts. Finally they would find themselves in a humiliating retreat in the face of an advancing Austrian army in late 1917 after the fall of the Italian forward position at Caporetto. Romania1 also decided to enter the war (August 1916) after promises by Britain and France for territorial compensation were made to it similar to those made to Italy. When in September Romania invaded Hungarian Transylvania to collect on those promises they were only briefly successful in holding that territory before they were thrown back by a joint attack of Austria and Bulgaria. Before the year was out Romania had to yield not only its capital city Bucharest but most of its land to the invading Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian forces. Romania was effectively knocked out of the war. Serbia is crushed

In the fall of 1915 Austria-Hungary and its allies Germany and Bulgaria joined forces to hit the Serbians hard. The Serbians were forced to retreat, leaving their capital Belgrade in enemy hands, even falling back into the Albanian mountains, and finally being chased down even there. Remnants of the Serbian army were finally, with British and French help, able to escape to Greece. In all, the Serbs lost over a million men (more than a quarter of its population and over half of its male population). The 1916 Brusilov Offensive

The year 1915 did not go well for Russia. The Germans pushed the Russians out of Warsaw as well as the Polish lands further to the east. But the Russians planned to open up an offensive in June of 1916 (the Brusilov Offensive) against the Austrians in the hope not only of relieving the German-Austrian pressure on the Russian Ukraine region but also in the hope of retaking some of the lost Polish territory. The offensive was designed also to relieve pressure on the French at Verdun, where the Germans had earlier that year opened a major offensive on the Western Front. The Brusilov offensive came to an end in September when both armies faced total exhaustion, and when Russian troops had to be withdrawn to try to help the retreating Romanians. The net result of this massive encounter between the two sides was the smashing of the Austro-Hungarian army, which subsequently would have to rely increasingly on German support to conduct its campaigns. But the offensive had also been very costly to the Russian army, in equipment as well as men. This would mark the high point of the Russian role in the war. The battles of Verdun and the Somme (1916)

In the late winter (February) of 1916 the Germans opened up a massive offensive against the French line at the fortress city of Verdun. They literally reduced to rubble the complex fortifications of Verdun, hoping to annihilate completely the French troops gathered there. It was expected that this would open such a huge hole in the French line that the French would be thrown in disarray and the Germans could then move on the French capital and end the war. Massive amounts of German power would be thrown into this operation. But the Germans had not counted on the stiff resistance that the French offered even amidst the rubble, and the French line held as more French divisions were brought into position by the determined French General Pétain. By July it was obvious to the Germans that their plan was not working. Verdun had been a gamble, which failed to yield any significant gains for the Germans despite the heavy costs involved (with somewhere between a third and a half a million casualties on both sides). By July much of the action now moved

north to the Somme River valley when on the first of the month the

British opened up a major summer offensive against the German line. The

goal was both to take pressure off the French at Verdun (which it did)

and do what the Germans had attempted to do at Verdun: open up a gap in

the enemy lines (which, as at Verdun, it did not do). Massed attacks on

German lines failed to dislodge the Germans and hundreds of thousands

of allied British and French troops died in the attempt. The attacks

continued through August, September (growing even heavier) and October,

until finally in November the rains turned the devastated land into

knee-deep mud and the offensive ground to a halt. An interesting new item of war was introduced at the Somme: the British tank. But the British had not yet learned to maximize its use with ground troops, and at this point it did little to impact trench warfare. 1"Rumania"

was actually the way the name was spelled at this time, although

"Romania" was not uncommon. Romania would finally become the

official name of the country in 1975.

|

The medieval Cloth Hall at Ypres beginning to be shelled by the Germans in November 1914

Ruins of

Ypres market square

(1915)

But the worst of all is

life in the Western trenches that get dug in as the lines of war stalemate

into a permanent line

of slaughter ... lines that will

barely move 10 miles either way

despite massive amounts of soldiers ordered to the deaths in order to move

those

lines

British

troops head "over

the top" for a skirmish with their German counterparts

A

British

training camp in

Northern France

– realistic preparation for the recruits for life in the

trenches

Troops

from

French Indo-China

(Southeast Asia) serving in the French army

The Krupp Gun Works at Essen

Women

manufacture artillery

shells in a French factory

The 1916 Battle of

Verdun ordered by the Germans illustrates perfectly the war's mindless

slaughter ... an action that achieved nothing but the pointless murder of thousands of

soldiers

German

cannon blasting the

Verdun Citadel in preparation for an assault – February 1916

Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv,

Munich

French being bombarded at Verdun

French

officer

machine gunned

down in a counterattack at Verdun – 1916

An

ammunition transport being

shelled by Germans

The British effort to take Passchendaele Ridge in the "Third Ypres" assault in 1917 fared no better

British batteries pounding

the German lines – 1917

Stretcher bearers mired in

mud in the Third Ypres – August 1, 1917

Destroyed German trench at

the Battle of Messines

Bapaume

pillaged by the Germans in 1917

"View of Ypres: Photograph taken from a flying machine"

| "The pitiful ghost of one of ravaged Belgium's most beautiful and historic cities. In the central foreground may be seen the roofless remains of the famous Cloth Hall, the largest edifice of its kind in the kingdom, begun by Count Baldwin IX of Flanders in the year 1200. Just beyond looms the scarred and desecrated Cathedral of St. Martin. On all sides are ruin and desolation, where three summers ago dwelt nearly 20,000 happy, thrifty people, engaged chiefly in the peaceful pursuit of making Valenciennes lace." |

War weariness sparks revolt

among French soldiers – May and June 1917

(probably encouraged by the news of

widespread soldiers' revolts among the Russians)

French soldiers begin to

desert

General Pétain meets with

troops to boost French morale

Starving

Berliners cutting

up a dead horse for food – 1917

|

|

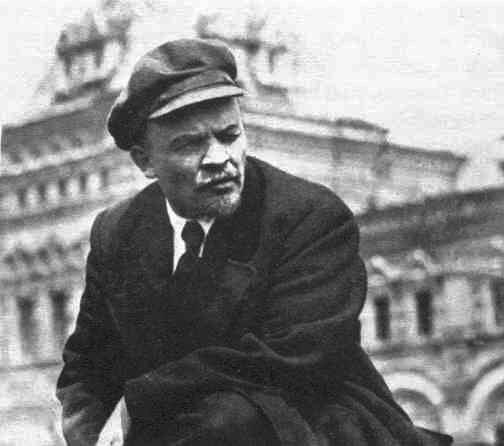

Although Russia's army greatly outnumbered its enemies, it lacked the supplies necessary to make it an effective fighting force. Weapons and ammunition were always in short supply, demoralizing the Russian soldier who was expected to fight on empty-handed. Russian civilians were well aware of these problems and were quick to blame the Tsar and his government for these scandalous shortcomings. Very unwisely, in September of 1915 the Tsar decided that he personally must lead the military from the front and left the governing of Russia to his wife. And the Tsarina in turn left matters to the nasty-smelling and crude mystic monk Rasputin, who made and unmade governments with his own personal appointments, further scandalizing the Russians in their dwindling respect for their imperial government. By the beginning of 1917 wartime shortages had hit the civilian population as cruelly as it had the military. Food in the cities was very difficult to obtain, and grumbling turned into a full-scale protest by Petrograd (St. Petersburg) workers (the Russian "February Revolution"),2 joined by masses of women. The protest built strength over the next days, and soldiers sent to restore order began to join the protesters. Word reached the Tsar at the front that

even his own bodyguard had joined the revolt, and under advisement of

his generals, Nicholas simply abdicated his throne (March 15). When his

brother Grand Duke Michael refused to take the throne, no other

Romanovs stepped forward to take the reins of government, thus bringing

300 years of Romanov imperial government to an end in Russia. All this activity now gave the outward appearance that Russia had just become a democracy. Actually what it had become was hardly decided at that point. However, from a certain vantage point, it could be claimed that now the war had taken on the character of being a great moral matter of democracy (Britain, France, Italy – and now Russia) against autocracy (the empires of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey). Seeing Russian developments in this light was, very importantly, Woodrow Wilson, the president of the United States. Eventually heading up the new Provisional Government was Alexander Kerensky, leader of the Social Revolutionary party, but also vice-Chairman of the powerful Petrograd Council or Soviet. However, understanding the dynamic of this war no more than had the Tsar, Kerensky made the fateful decision to keep Russia in the war, to pursue Russia's new "democratic" cause (and redeem Russia's tarnished honor). But Kerensky proved no more able to keep Russia together in the face of the demands of war than the Tsar, and the Russian soldiers now begin to protest against the new government. This gave the Bolshevik leader Lenin the opportunity to seize power (the Russian "October Revolution")3 in both Petrograd4 and Moscow, on the promise of taking Russia out of the War. This clever move made him instantly more popular among the Russian commoners than their new democratic champion, Kerensky. Lenin soon made good on his promise, and – with a Russian-German armistice in December – took Russia out of the war. Russia was at this point finally out of the war, but tragically only to face now a new one – an internal civil war among various Russian groups, one that would prove to be even more devastating to Russia than had been the Great War that they had just dropped out of. 2Occurring in early March on our Western calendar. 3Occurring in early November on Western calendars. 4St.

Petersburg was renamed "Petrograd" during the War to give it a more

Russian sound. Soon it would be renamed yet again as "Leningrad,"

in honor of the leader of the Communist Revolution in Russia. And

then with the fall of the Communist system in Russia at the beginning

of the 1990s, it would retake its original name, St. Petersburg.

|

Father

Grigori Efimovich

Rasputin and adoring women of the Russian nobility – 1916

(just prior to his

murder)

The

last glory days of the

Russian Imperial household

From left to right, Grand

Duchess Anastasia, Grand Duchess Olga, Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarevich

Alexei,

Grand Duchess Tatiana,

and Grand Duchess Maria, and numerous Kuban Cossacks, ca.

1916.

Soldiers

riding through the

streets of a riotous Petrograd -- March 11-12

precipitating the Tsar's

abdication

Troops from the Petrograd

garrison who take over the Tsar's Winter Palace after his abdication

Russians,

hearing reports

that German cavalry have broken through Russian lines,

have thrown down their guns

and are in full flight – summer 1917

Soldiers

demonstrating for

Communism

Lenin

speaking to a massive

Petrograd crowd on behalf of the Communist

Revolution

Russian and

German troops

fraternizing upon the news of an Armistice

worked out by Trotsky with

the Germans in December of 1917

The signing

of the Brest-Litovsk

Treaty

| The treaty took away a third of Russia's population, half of her industry and nine-tenths of her coal mines. But it enabled the Communists to focus their full efforts at securing their rule over what remained of the former Russian Empire. A huge and extremely bloody civil war was about to begin. . |

|

|

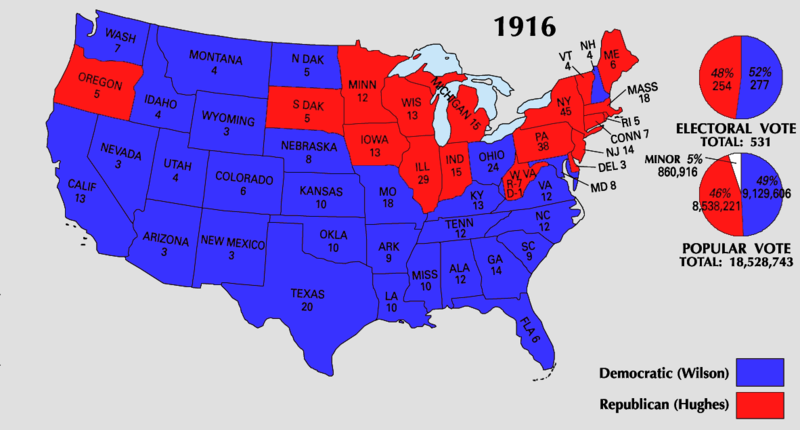

Wilson was American president when World War One broke out in 1914. He correctly understood that this war was merely an ego battle among European empires and that the United States had absolutely no reason to get involved. In 1916 he ran for reelection as president in part on the position that "he kept us out of war." The one-sidedness of American 'neutrality

It had never been easy trying to stay neutral in a war that affected America's vital business in trade with Europe, as European enemies attempted to isolate each other from resupply by America on the high seas. The British effectively put in place a naval blockade against Germany which prevented the Germans from receiving much-needed shipments of even food coming from America, both from the United States and from South American countries such as Argentina, which were also major exporters of food products. Americans complained bitterly about the way the British prevented neutral America from conducting trade with Germany in non-war goods. But the British ignored these complaints. Eventually the Americans responded by simply devoting their trade as a "neutral" nation to Britain and its ally France, which rewarded American businesses richly by purchasing everything America could send them. Germany was thus left out in the cold as its people drew closer to starvation. The Germans countered by attempting to establish a blockade of their own around Great Britain, using submarines as the effective instrument. But submarines were viewed as inhuman instruments of war because they could not rescue the sailors of ships they had sunk. Thus the British blockade took on a legitimacy that the German blockade failed to receive in the eyes of Americans (although actually the German sinking of American shipping was quite light). This played into the hands of the English propaganda machine operating very effectively in America with the American press (the Germans never really learned how to shape the narrative of events in Europe that could draw the sympathy of Americans). The sinking of the Lusitania

In May of 1915 a German U-boat sank the massive English luxury liner Lusitania just off the coast of Ireland, with nearly 1200 people drowned, over a hundred of whom were Americans, including some very prominent citizens. The Germans had warned ahead of the dangers of bringing a luxury liner into the war zone, especially with huge amounts of contraband war materials in the ship's hold. Indeed, what the Lusitania had been doing was very illegal under the international rules of war as they stood in those days. Nonetheless American fury was immense, and the Germans backed down by promising that no more civilian liners would be targeted. For the moment the crisis passed and America maintained its neutrality, as lopsided as it was in the way it favored only Britain and France. But the Germans could do little about it, unless they wanted to make an enemy of America.

|

A

Pro-Germany march in Chicago – 1914

An

American ship hit by a

German U-boat – 1915

The

Lusitania – sunk

May 7, 1915 – torpedoed by a German submarine

with 1,198 people – including

128 Americans – drowned

An American Lusitania victim being carried by Irish pallbearers

|

Wilson’s War “To Make the World Safe for Democracy”

|

The Germans resume submarine warfare

But pushed to total frustration by a starving Germany, the Kaiser in early 1917 made the fateful decision to resume U-boat attacks on shipping, hoping to force the Americans to take a truly neutral side in the war. This resumption of U-boat attacks on American shipping heading to Great Britain and France instead served only to outrage the Americans, an outrage so great that it easily pushed America towards a readiness to go to war with Germany over this matter. Then there was the incident of an incredibly stupid telegram sent around this same time by the Germans to the Mexicans – and intercepted by the British (and purposely placed in American hands) – inviting the Mexicans to go to war against America under the promise that the Germans would help them recover territory previously lost to the U.S. if they joined the Germans in this struggle. The Mexicans of course were not that foolish, and the telegram was ignored. But its exposure had helped immensely to stir up the demand of angry Americans for war against Germany. But were these sufficient reasons in themselves to now take America into the War? Was the situation for America any different than it was in 1915 when Wilson was able to use diplomacy to keep heads cool and America out of the war? But it was actually events in Russia that would tip the balance for Wilson towards the decision to finally take America into the European war. The impact of the Russian Revolution on Wilson's thinking

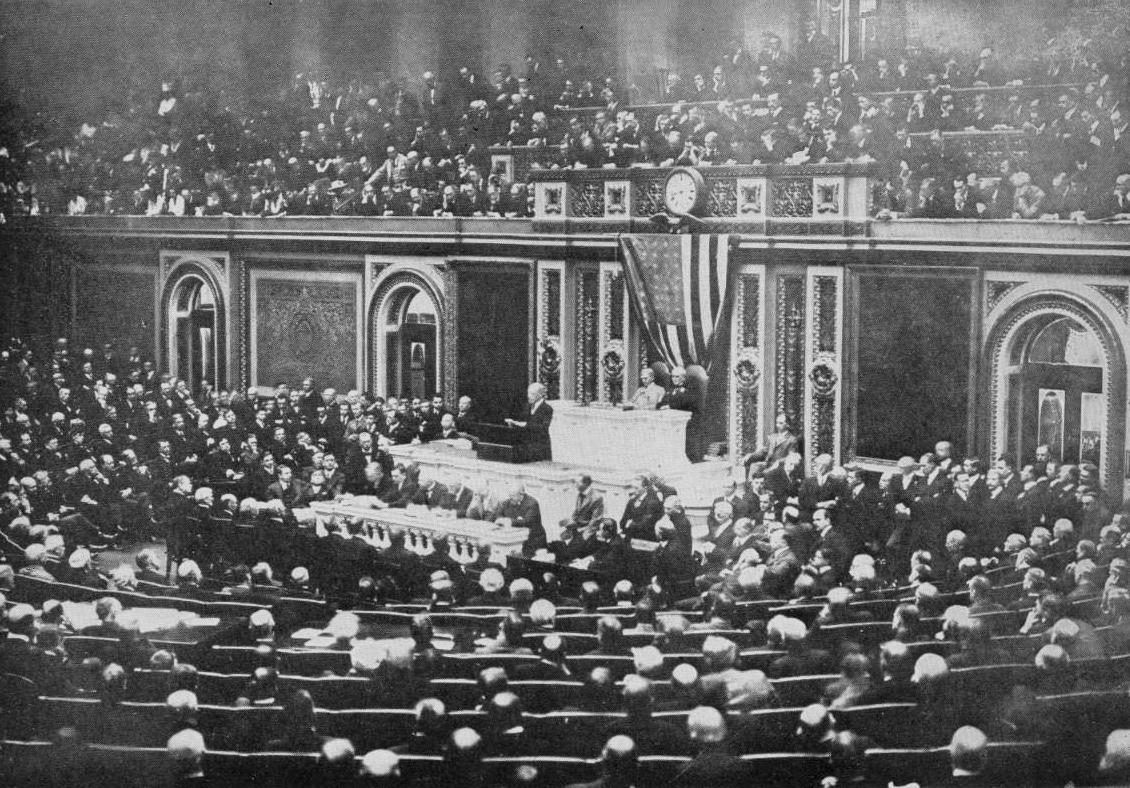

Subsequent to the February Revolution – which occurred just as Wilson was being installed for his second term in office – Wilson no longer viewed the European conflict as a mere brawl among European powers. The collapse of the Tsar's imperial government in Russia in early 1917 and its replacement by a democratic Provisional Government certainly to Wilson gave the war a new look. Now on one side were the democracies – Great Britain, France, Italy and, complements of the recent Revolution in Russia, that country as well. Opposing them were the imperial governments ("autocracies" as Wilson termed them) of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Ottoman Turkey. To Wilson the war now took on the appearance of being the good guys versus the bad guys. Now the war seemed to Wilson to have a moral cause worthy of American involvement. Thus on April 2nd (1917) he called Congress together to request a declaration of war. America's crusade for democracy, against evil autocracy

In his speech delivered before Congress,118 Wilson waxed eloquent (and amazingly wrong) in his appraisal of how recent Russian events had changed the game:

This was an amazing misrepresentation of Russia in every way possible. It was also very characteristic of the Romantic view of human nature held by very privileged members of the American intellectual class – the class that Wilson himself belonged to – members of which tended to be far, far removed from the harsh realities of life lived by the vast majority of people on this planet. These were harsh realities (soon to be

encountered with America's entry into the pointless war) that sadly not

only Wilson was about to encounter but also the American people as

well. Instead of serving some great cause of democracy, America would

end up serving only the grim imperial interests of Britain and France,

and little else. And ultimately, soon coming face to face with this

unpleasant reality, it would break the spirit (and health) of Wilson

... and, in odd ways, that of the American people. "To make the world safe for democracy"

In any case, Wilson represented the war as the opportunity to engage America in another one of the crusades of political reform that so captivated the imagination of this autocratic reformer. To the American people he now proclaimed that the war was an historical struggle between the forces of world democracy and the tyranny of autocracy – and that America needed to get involved on the side of democracy, "to make the world safe for democracy." He and the American people (their sons, brothers and husbands) needed to take up the challenge of defeating evil autocracy and bringing democracy – and consequently full political freedom, prosperity and justice – to the world. Wilson's Idealism was boundless. And his mind was made up on this matter.5 He was going to sell the war to the American people not only on how this was going to spread democracy everywhere in the world – but that in doing so this would finally bring a lasting peace to the world. To Wilson, democracies were always presumed to be reasonable societies – not grasping, not bullying and brawling like European autocracies of the Old World. According to Wilson (and other American and European Idealists or Humanists), by natural instinct democracies used calm reason in pursuing their national politics – and sought merely for international understanding in their engagement in the world of international relations and diplomacy. Wilson thus fashioned the idea that the war which broke out in 1914 had been nothing more than the result of the disastrous policies of the ruling classes of the autocracies – rather than the passionate nationalist urge of the masses or commoners of nearly all European nations. Also, of such an autocratic personality himself, Wilson did not bother to truly check out his claims that Germany was the autocracy and Britain (and now Russia!) the world's true democracies. He had simply made up his mind himself on the subject. End of discussion. However, not only were Germany and Britain governed in a fairly similar manner by cousin kings, Germany had enacted some of the most socially progressive legislation at a time when Britain's treatment of its own industrial workers was still a major problem in that country. In any case, in his speech before Congress Wilson outlined clearly his lofty cause he was asking young Americans to give their lives for:

"To make the world itself at last free."

According to Wilson, in the bright new world that would unfold with democratic victory, people everywhere would be ruled by unselfish reason rather than by greedy, brute force. Once freed from the tyranny of power and power holders (the imperialistic autocrats), mankind would live by the higher moral power of logic and Truth. Thus this last great wartime struggle, no matter how violent it might become (and how many young Americans it might kill), would be well worth the terrible sacrifice – for it would "make the world itself at last free." His concluding remarks state the matter clearly:

America's democratic allies have a different agenda

Tragically, Wilson's take on the war was not exactly how America's new allies Great Britain and France saw the war. At their home front, in their national capitals, they were indeed democracies. Actually they were empires too, with both Britain and France controlling vast empires in Africa and Asia – and with clear intentions of extending their imperial grip into the Muslim Middle East once the Ottoman Turks were knocked out of the way. But they played along with Wilson. They were certainly glad to get American help in crushing their "autocratic" enemies, and thus played along with Wilson's crusading Idealism. American assistance would likely break the terrible stalemate that had set in on the war and finally bring their side to victory in this long and deadly (and largely pointless) struggle. 5But

like Wilson, ironically (or maybe not), the reformist American

Progressives (with the strong exception of Wisconsin Senator Robert M.

La Follette) were the ones who had for years taken the position that

America needed to join the war. It was the conservatives who had

long held out in opposition to such involvement.

|

Declaration and mobilization

President Wilson appears

before Congress,

requesting a Declaration

of War against Germany

– April 2, 1917. The Senate passed the Declaration

on April 6: 82 in favor, 6 opposed;

the House passed it: 373 to

50.

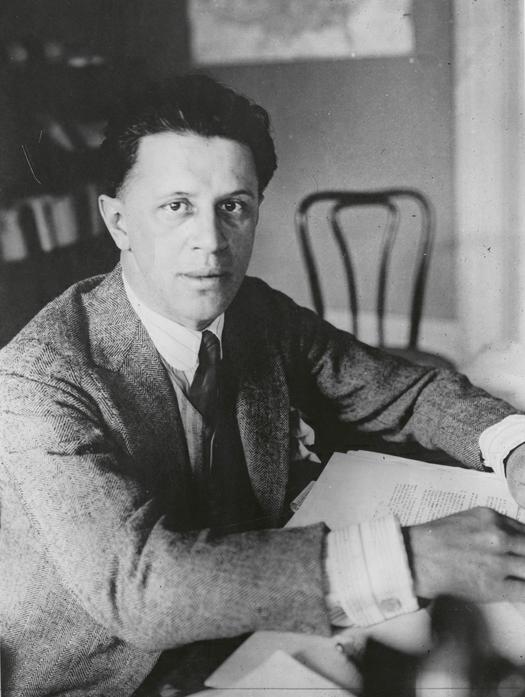

The strong Progressivist,

Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr.

He

would

strongly oppose

the U.S. entry into the war – and suffer tremendously as war

fever rose

rapidly in America (but

in

1957, a Senate Committee

selected La Follette as one

of the five greatest U.S. Senators, along with

Henry Clay, Daniel

Webster, John C. Calhoun,

and Robert Taft.)

Col. E.M. House – special

advisor to President Wilson

Joseph Patrick Tumulty – along with Col House, Wilson's alter ego

Robert Lansing – Anglophile

Secretary of State (who had his difficulties with Wilson)

Wilson and his second wife

Edith (married December 1915)

She became a very assertive,

but not particularly politically astute, advisor to the president

|

Gearing up

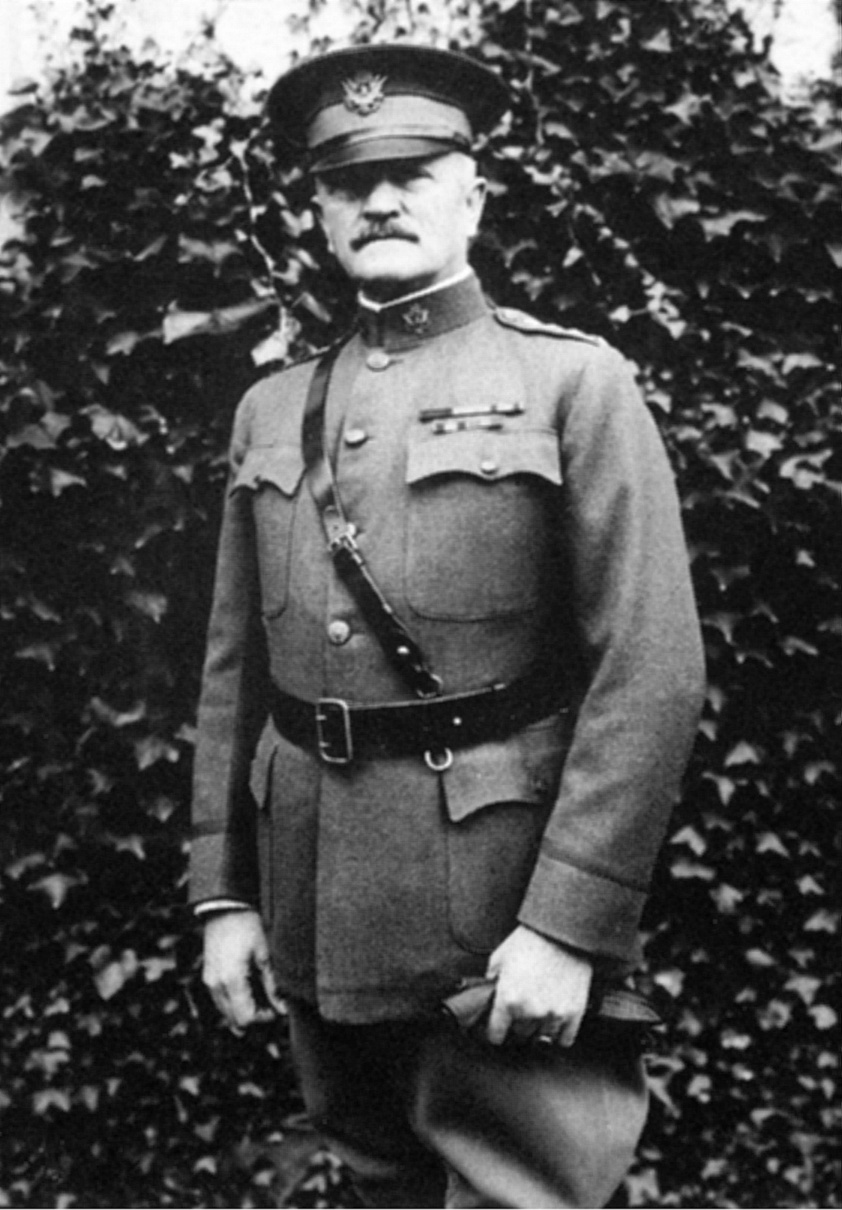

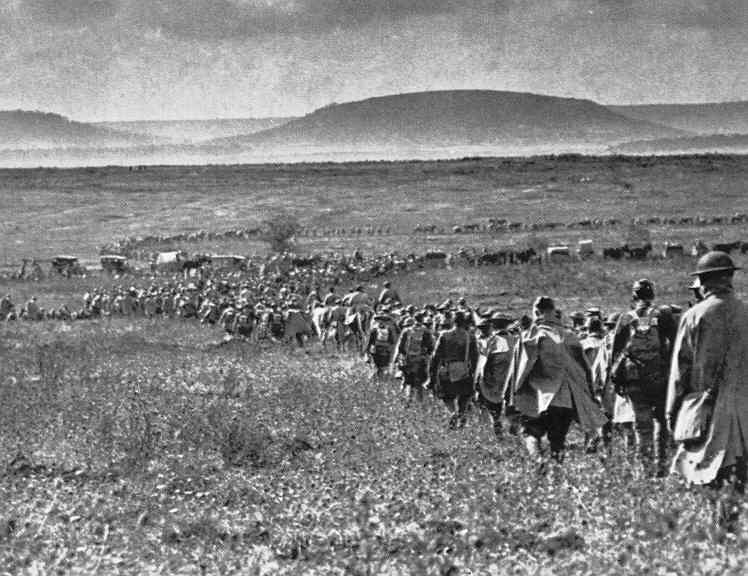

In any case, America was not immediately ready to go to war. The U.S. Army was very small in size, there having been since the end of the Civil War (and the American-Indian wars) no apparent need of a large force, except to fight nationalist insurgents in the Philippines (early 1900s) and Mexican raiders set loose to do damage along the Mexican-American border (Pancho Villa was still conducting raids along the border at the time of America's entry into the Great War in Europe). General Pershing was sent to Europe in June of 1917, at the head of a small American military force, to give tangible evidence of America's commitment to the war cause there. But before America could get seriously involved, millions of troops would have to be trained for battle. It would not be until the late spring of the next year, 1918, before the Americans would arrive in strength in Europe. The Americans join the fight

The French

and English attempted to direct American troops into their own ranks as

replacement troops for their exhausted armies. But American commanding

General Pershing refused to use American troops as mere replacements in

the ranks of the French and British armies. He demanded that they be

given their own sector along the long line of battle, where they could

fight under their own flag as a fully American army. The allies

reluctantly agreed, having no basis on which to refuse this American

demand. And thus in early 1918 Americans began taking their position at

the Belleau Wood and St. Mihiel sector near Verdun. Having helped to push back the German lines in those sectors in the late summer they then took on the Germans dug in within the Argonne Forest, which proved to be much slower going and more murderous for the Americans. But the soldiers conducted themselves well. |

General Pershing arrives

in France – June 13, 1917

"Lafayette, we are here!"

Pershing speaking at Lafayette's

tomb outside of Paris

(actually the words were

pronounced elsewhere by another American officer but attributed

to Pershing because of the

censor's refusal to mention any other US officers by name)

General Pershing meeting with French leaders Poincaré and Pétain

George Creel – the head (and

actually sole active member) of the United States

Committee

on Public Information.

He sponsored the "Four-Minute

Men"

(some 75,000 of them by war's end) who went about the country

drumming

up popular support for America's participation in the war

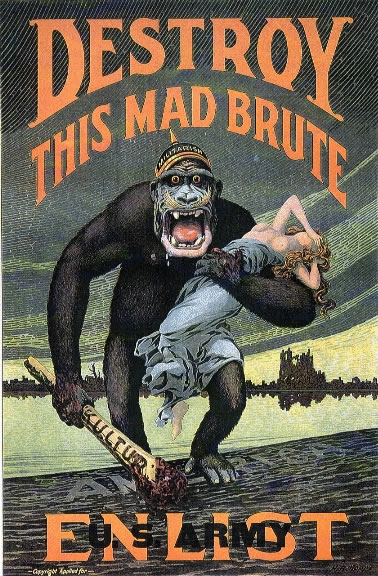

The US Public Information

Committee adopted this British poster

in an effort to stir up American

war fever

American recruits

American conscripts are sworn

in

Former President Roosevelt

addressing American trainees at Camp Grant, Illinois

American recruits ready to

go

New York – 5th Avenue – Flag-waving

well wishers

send off the American boys to the European War

An American family saying

Goodbye

A New York National Guardsman

saying goodbye to his family as he heads off to war – 1917

The War shifted political alliances – at least temporarily

Suffragettes register to

work as war volunteers during world war I

But not everyone bought into the shift

"Woman anarchist leader and

aid in draft war. Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman

convicted of conspiracy

against draft law and sentenced to two years

in penitentiary and fined

$10,000 each, July 9, 1917."

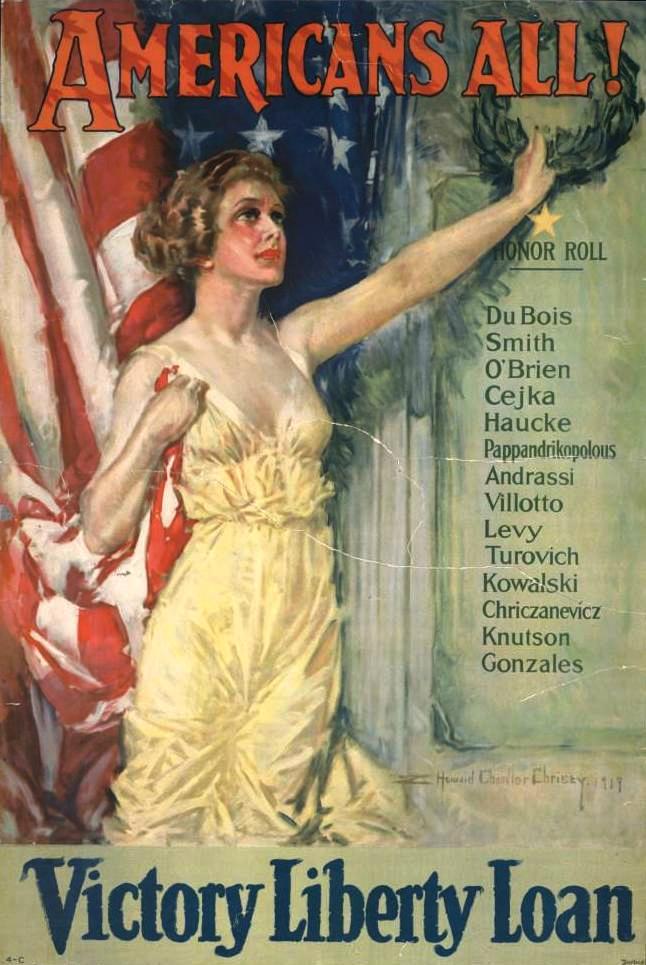

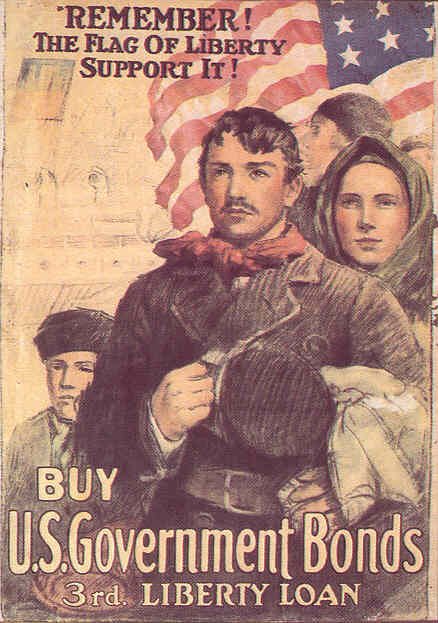

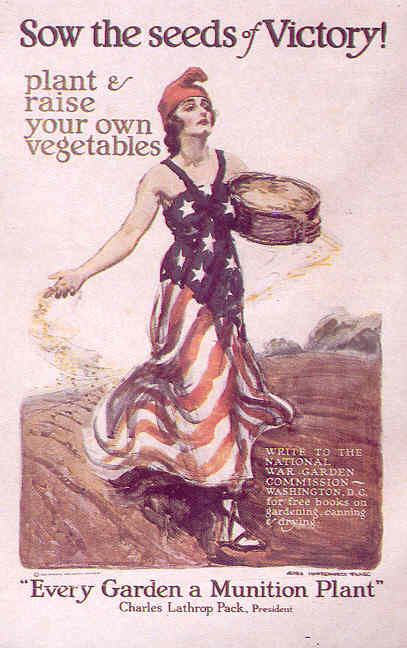

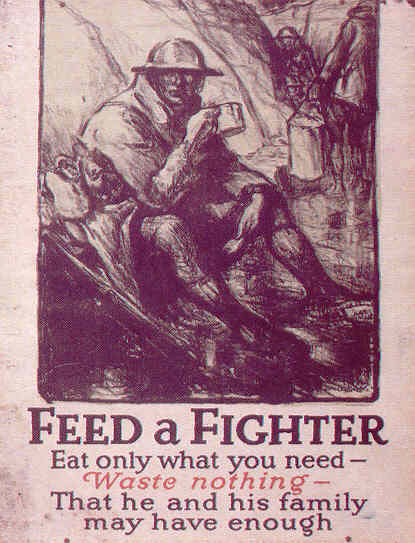

To finance the War a major

campaign to raise money via war loans got underway

(American incomes were not

yet taxed directly by the Federal Government)

Color posters by Howard Chandler

Christy

Before the end of the year American troops begin to pour into Europe

American troops arrive in

London – August 1917

Newly arrived American troops

marching through London

American troops welcomed

in London – 1917

New American troops – winter

1917-1918

|

Actor-celebrity Douglas Fairbanks

encourages deeper financial support for the War –

New York, Wall Street – 1918

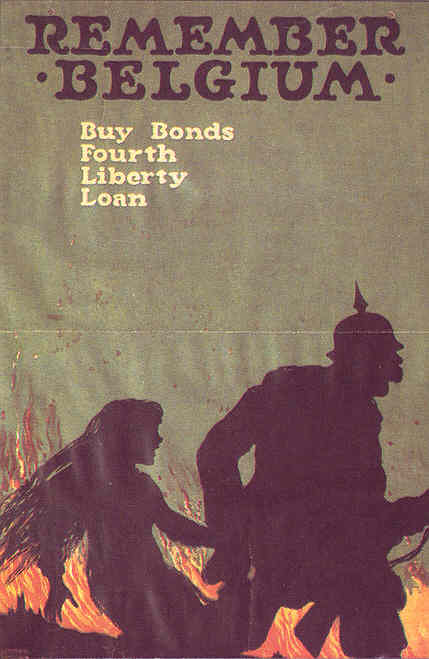

American War Posters

"Liberty Loan Choir sings

on the steps of City Hall, New York City during third Liberty

Loan campaign. Bishop William

Wilkinson leads the choir"

Women welders at the Hog

Island shipyard near Philadelphia

Women workers in ordnance

shops, Midvale Steel and Ordnance Co., Nicetown, Pa.

Hand chipping with pneumatic

hammers – 1918 – photo by Lt. Lubbe

Women immigrants to America

from 5 different countries sewing an American flag

American women operating

farming machinery

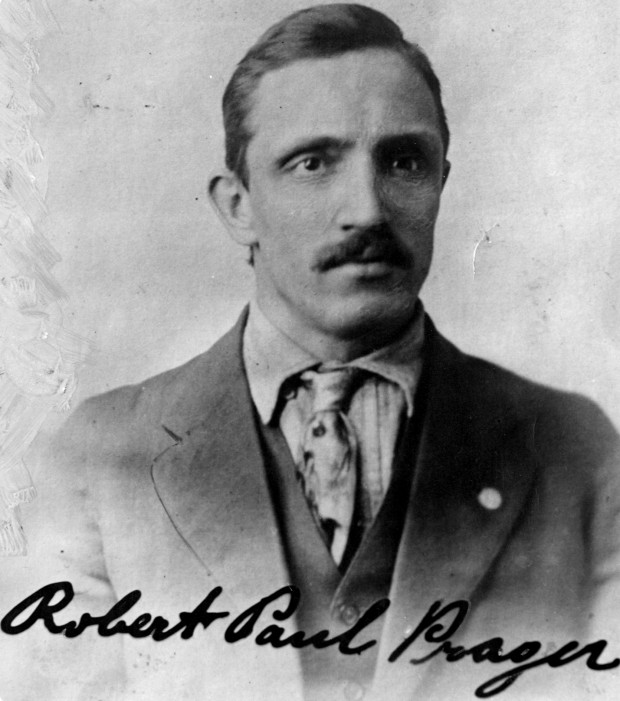

The downside to all this patriotic enthusiasm

was the anti-German xenophobia it unleashed:

Mob hysteria leads to the

lynching of a German immigrant – Robert Paul Prager

April 5, 1918 in

Collinsville, Illinois

"Look Back: Robert

Paul Prager Lynching, 1918"

St. Louis Post Dispatch – May 25, 2012

"Look Back: Defendants

walk in lynching of German immigrant in Collinsville in 1918"

At the trial on May 28th,

1918 all were acquitted of murder by the jury

|

|

In January of 1918 Wilson went before Congress to outline what he expected to be the specific terms of the peace that America was fighting to secure. The terms were presented as Fourteen Points, including the end to secret treaties (which Wilson supposed were the primary cause of the war in the first place); the guarantee of full freedom of all navigation on the high seas (a major source of American annoyance with both the Germans and the English); the adjustment of territories such as would restore Russia, revive Poland and return to France territory lost to Germany in 1871; the opportunity for independence of nations part of the Austro-Hungarian and Turkish Ottoman Empires; and most importantly (in Wilson's eyes), the creation of a general association of nations to guarantee the political independence and territorial integrity to all states, large or small. This last point was the intellectual foundation for what would become the first truly international diplomatic organization: the League of Nations. He made it clear that even for the Germans he sought only a fair or equitable peace – though he would negotiate such a peace with only a German delegation representing the majority members of the Reichstag (the German National Assembly) and not the "military party and the men whose creed is imperial domination." This was a clear indication that America would not deal with the Kaiser but instead with only a German group representing supposedly the broader interests of the people of Germany. In theory, this was all very noble. But it would leave the Germans at the negotiating table facing very hostile adversaries – at the same time having to operate from a position of incredible political weakness. Because of Wilson's requirements, Germany’s national interests would be defended by a group of negotiators possessing very little German political or emotional support by their own German people to work from. Consequently, Germany would be walked over by France and Britain – despite Wilson’s protests – and ultimately leave Germany in the future itching for a rematch to readjust the unfair outcome of the peace talks. Hitler would soon play big on this German understanding of what happened under Wilson’s Armistice. Wilson's 14 Points

|

|

|

Meanwhile the Germans were having tremendous difficulties keeping up their end of the war. This two-front war was draining down Germany's economic and spiritual strengths to a dangerous low. In December of 1917 the Germans signed at Brest-Litovsk a treaty with Lenin's Communist government in Russia, in which the Germans agreed to halt their assault on Russian territory – thus freeing the Russian Communist Red Army to focus its efforts completely on defeating the Russian White Armies made up of a poorly united coalition of pro-Tsarists, Cossacks, ethnic minorities and pro-republicans. Part of the payoff for the Germans was the huge German territorial gains in Eastern Europe given up by the Russian Communists. But the main reason the Germans had agreed to this treaty was that they would then be free to rush the vast number of German troops massed in the Russian Front back to the Western Front. With this new concentration of German troops on the Western Front they could then break through the French and British lines and grab Paris, thus collapsing French resistance and ultimately ending the war itself before the Americans could arrive in number in Europe in the spring of 1918. Indeed, that next spring of 1918 the

French and British lines initially were pushed back heavily in the face

of Germany’s new offensive (begun in March), but then held firm, so

that overall the Germans failed in reaching their objective: Paris. By July the Germans found themselves merely exhausted all the more through this desperate effort. Meanwhile back in Germany, the population was finding itself on the brink of starvation, and movements to pull Germany out of the war were starting to form in opposition to the Kaiser's determination to fight the war to the finish. |

Marshall, p. 293

US troops being transported

to the trenches – 1918

Pershing address U.S.

Marines – June 1918

American Signal Corpsmen

donning gas masks

Marine receiving first aid

before sent to hospital in rear of trenches.

Toulon Sector, France. March

22, 1918. Sgt. Leon H. Caverly, USMC.

"Negro troops in France.

Picture shows a part of the 15th Regt.

Inf. N.Y.N.G. organized

by Col. Haywood, which has been under fire." ca. 1918. IFS.

US troops resting up after

the bitter fighting at Belleau Wood – June 1918

Foch and Pershing in one

of their few pleasant moments together – June 1918

General John Pershing – General

Headquarters, Chaumont France – October 19, 1918

photo by 2d Lt. L J.

Rode

|

Marshall, p. 340

Americans advance against the Germans' St. Mihiel salient

American troops moving forward

into the St.-Mihiel salient – September

A 75-mm. American gun crew

targeting the St.-Mihiel salient

American charge against the

St.-Mihiel salient

(one doughboy has just taken

a hit from German fire)

A French couple in Brielles-sur-Bar

greeting American soldiers

who have just delivered them from four years

of German occupation

They then move into the Argonne

Forest

– where fighting proves to be vastly more difficult

Because of their victory

at St-Mihiel,

American troops head into

the Argonne Forest with spirits running high

American troops going forward

to the battle line

in the Forest of Argonne

in Renault FT-17 tanks. September 26, 1918.

But the Argonne Forest affords

only a very painful inch-by-inch advance for men of the 23rd Infantry

Machine gunners of the German

Fifth Army in the Argonne

A makeshift-hospital in a

bombed-out French church

treats American wounded

from the first day's action (September 26)

American soldiers advancing

on a bunker

October

Fierce fighting accompanies

the American advance through the villages of the Meuse valley

(a dead German lies next

to the tank)

Young Brigadier General Douglas

MacArthur (38) in a French manor

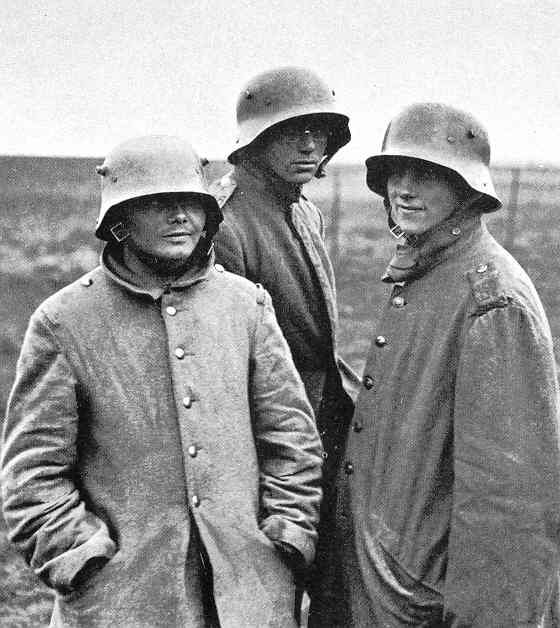

The number of German prisoners now grows astronomically

A long line of German prisoners

near Amiens escorted by a handful of Australian guards

Young German prisoners seeming

relieved that the action is all over

Very dis-spirited German

soldiers

German prisoners carry a

wounded comrade to an American aid station

|

Baron Manfred von Richthofen

(26) – Germany's "Red Baron" air ace for 20 months

(80 confirmed kills). He was shot down near Amiens on

April 21, 1918

"Capt. Edward Rickenbacker,

America's premier "Ace"

officially credited with

22 enemy planes and the proud wearer

of the French War Cross

as he appeared upon his arrival on board the Adriatic"

Eddie Rickenbacker (27),

former race car driver – by war's end an American air ace

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges