|

|

The "Peace" of 1919: An overview The "Peace" of 1919: An overview Armistice

on the Western Front Armistice

on the Western Front

The 1918

Spanish Flu epidemic The 1918

Spanish Flu epidemic Managing

Allied grudges and greed Managing

Allied grudges and greed

The

new face of Europe and its former empires The

new face of Europe and its former empires But

America retreats into

isolationism But

America retreats into

isolationism The Women's suffrage campaign The Women's suffrage campaign

The

Socialist-Communist contribution to

Democratic Idealism The

Socialist-Communist contribution to

Democratic Idealism The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 470-475. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

The

disappointing

peace

But Wilson's peace ultimately does not work out as he had planned. Wilson attempts

to negotiate a fair end to the slaughter with his Armistice – but fails

to connect American power with American diplomacy – and the English and

French take the opportunity to pounce upon the exhausted Germans to wreak

an expensive revenge. Probably no English or French politician who

failed to bring home to his people some major exaction of retribution against

the Germans would have had a political future.

Wilson hopes to undo the unfairness of such "peace" terms with the creation of a new League of Nations, an international deliberative body which he hopes will provide the forum for more rational reshaping of the post-war world – when tempers have had a chance to cool down and diplomats are more able to think clearly and fairly. However the extensive commitment required of membership in the League alarms American Senators when Wilson’s League of Nations idea is put before them as a treaty requiring Senatorial ratification. But Wilson will hear of none of their complaints – unwilling to hear of any opposition to what he, ever the Idealist, considers to be a plan whose perfection must not be compromised. The net result of Wilsonian "purity" is that the Senate fails to ratify – and America does not join the League (the only major nation not to do so). Without American power linked to League action, the League is condemned to effectiveness only on very minor matters that do not demand a strong international hand. The German sense of betrayal

Furthermore, the betrayal of Wilson’s promise of an equitable peace, to which the Germans thought they were agreeing when they laid down their arms, will become the source of German ideological opportunity for those (Hitler and his Nazis) who seek to exploit this sense of betrayal to overthrow Germany's new "democracy" and institute a Neuordnung (New Order) in Germany. In short, the "peace" of 1919 merely sets the scene for a return engagement 20 years later in the form of World War II Chaos among the "losers." Russia is plunged into a long and bloody civil war (1918-1923) between Lenin’s Communist "Reds" and the coalition of Kerensky’s and the Tsarist’s "Whites." More soldiers and civilians die from this civil war than had died during the Great War. The decrepit Ottoman Empire is taken over by "Young Turks" who want to modernize the Turkish nation – and purify it by ridding it of the many non-Turkish minorities living within its borders. Germany forces the Emperor Wilhelm to abdicate and comes under a Weimar Republic which is challenged on all sides by Germans who have no love or understanding of republican democracy – especially one associated with the stigma of national defeat. The Austro-Hungarian empire is broken up into a number of mini-states, each of whose political viability as new "democracies" is questionable. Poland is restored out of territorial loss of Russia, Germany and Austria – with no tradition of democracy to guide it into the new era of democracy ... and existing as a vulnerable target should its neighbors recover strength enough to grab back their lost territory (which they do in 1939 – starting another World War in Europe) |

|

|

Armistice (November 11, 1918) ends the war

Ultimately Wilson's offer of a fair and just peace was heard in Germany, now wavering in its loyalty to the Kaiser. Inquiries were sent to Wilson at the beginning of October 1918 about the possibility of a cease fire. Then when around the same time the Allied armies broke through Germany's heavily defended line of defense, the Hindenburg Line, the Germans realized that the war was finally truly over for them. But Wilson's requirement that the Kaiser abdicate was a major sticking point. Then, inspired by the Russian Revolution of the previous year, in late October first sailors, then soldiers, then workers joined a growing revolt and simply took command and set up Soviet-style councils in various cities across Germany. Political chaos resulted, especially when the two wings of the large Social Democratic (Marxist) Party fell into fighting over whether or not to accept Wilson's peace offering – and then move quickly to set up a Soviet style Communist government in Germany – or instead redesign Germany as a parliamentary republic. Ultimately most of the soldiers and workers threw their support to the pro-parliament Social Democrats (led by Friedrich Ebert), who took control of Germany's government on the 9th of November after Prince Max announced the end of the German monarchy. Realizing that he had lost all political support, the next day Kaiser Wilhelm went into exile in the neutral Netherlands. Meanwhile Germans had taken up discussions with Wilson about an Armistice, which they were now willing to accept – on the basis of his Fourteen Points. Wilson agreed. However, America's allies, Great Britain and France, had no intentions whatsoever of honoring Wilson's peace terms, as they sought unconditional surrender of Germany and nothing less. They had gone along with Wilson's Fourteen Points only because they needed American aid and because they had recognized the propaganda value these had in undermining the Kaiser's political authority in Germany. Unaware of what was actually going on politically within the camp of its adversaries, the Germans complied with Wilson's demands and declared at Weimar the creation of a German republic (thus known as the Weimar Republic) and announced their willingness to accept an Armistice based on Wilson's Fourteen Points. Thus at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of the year (November 11th 1918) the guns finally fell silent in Europe for the first time in over four years. The war was over

|

The trains which brought

the two sides together at Compiègne for Armistice negotiations

November

1918

Officers in the forest of

Compiègne after reaching an agreement

for the armistice that ended World

War I.

This railcar was given to Ferdinand

Foch for military use by the manufacturer,

Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits.

Foch is second from the right.

President Wilson reading

the Armistice terms to Congress. November 11, 1918.

photo by Sgt Vincent J.

Palumbo.

National Archives

Armistice celebrations in

the trenches

Jubilant Harlem Hellfighters

(369th Infantry) – on return from Europe

after serious combat against

the Germans (they were the first to reach the Rhine River)

(3/4s of the 200,000 "Colored"

troops served as menials during the war)

National Archives

US soldiers excited to be

leaving training camp at Camp Dix, New Jersey – late 1918

(122,500 soldiers were killed

or missing, 237,135 wounded during the war)

National Archives

Medal of Honor and Croix

de Guerre winner Alvin York and his mother back in Tennessee

(in the 1918 Meuse-Argonne

offensive he charged a German machine-gun nest by himself,

killed 25 Germans and captured

132 others in two separate forays)

Armistice celebrations in

Paris

Londoners celebrating the Armistice

Londoners celebrating the

Armistice

|

|

Whereas the war had caused approximately sixteen million deaths, a flu which struck broad sections of the world (including America) in 1918 within mere months killed three times as many people. The flu hit in the spring of 1918 – but involved few deaths. But when the disease reappeared in the fall of 1918 – it was devastating. Age, health, city or country-living made no difference in its attacks. Half a million Americans died from this flu. And those it did not kill, it produced permanent effects for approximately a quarter of the US population. In a few short months it lowered life expectancy in the US by twelve years. And thus it was that as 1919 came into view, it was with much hope that the Western world greeted the first year since the end of the war – and the devastating Spanish flu. Hopefully much, much better days lay ahead.

|

Removing the body of a soldier killed by the influenza virus

Seattle policemen masked

against the Spanish flu – December 1918

National Archives

A street car conductor in Seattle

not allowing passengers aboard without a mask. 1918

National Archives

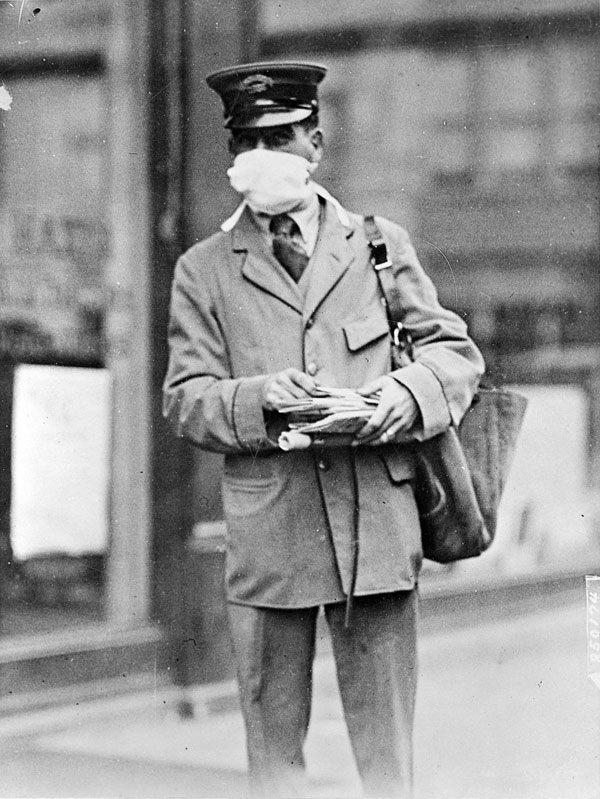

A mailman in New York

wearing mask for protection against influenza.

New York City, October 16,

1918

National Archives

A nurse wearing a mask as

protection

against influenza. September 13, 1918

National Archives

A typist wearing mask, New

York City, October 16, 1918

National Archives

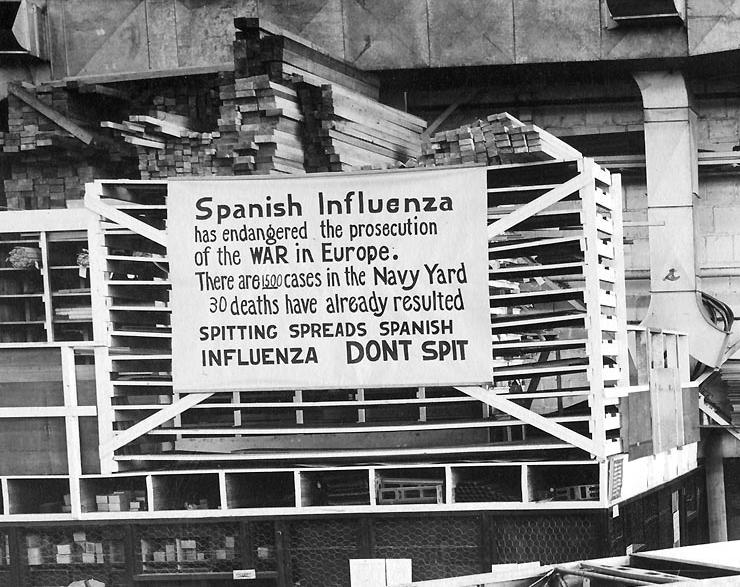

An influenza precaution sign

at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia October 19, 1918

National Health

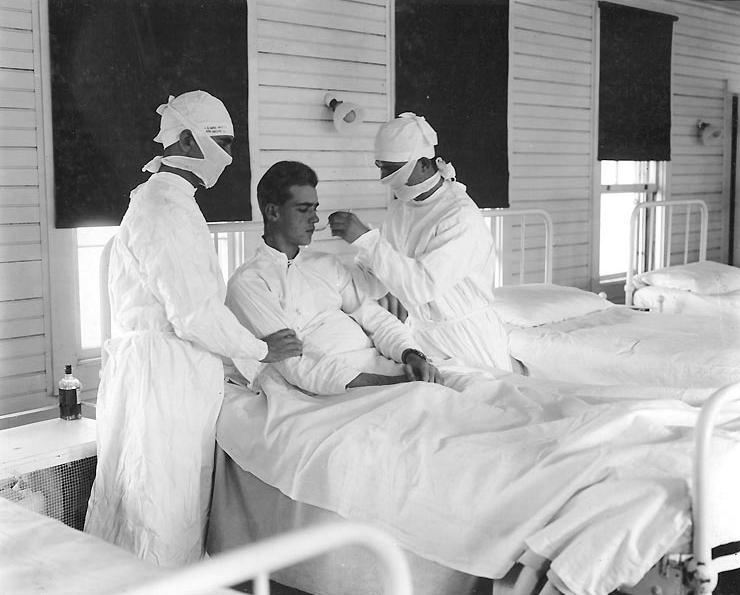

Treating an influenza patient

at Naval Hospital – New Orleans

National Health

Crowded sleeping area at

Naval Training Station, San Francisco

National Health

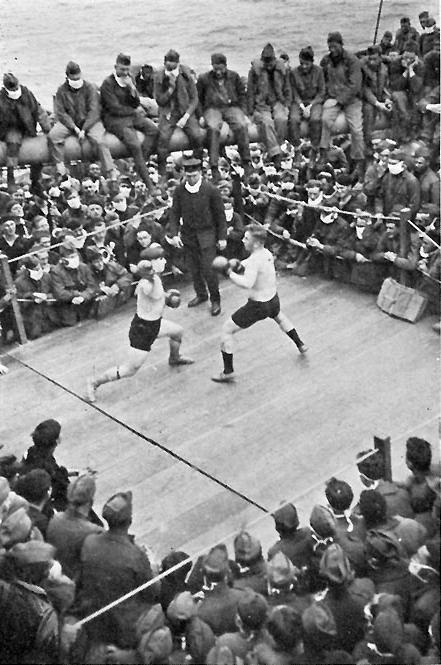

A boxing match on the USS

Siboney – with many spectators wearing protective masks

National Health

|

|

The "Peace of Versailles"

But tragically, reality would soon deliver a huge, disappointing blow to such hopes, and especially to the expectations of a triumphant Wilson, when all the warring parties sat down together to work out the specific terms of the peace that had looked so promising as 1918 came to a close. Being the Idealistic Humanist that he was, Wilson failed to connect American power with American diplomacy (much less even attempt to understand the dynamics of international power), and thus the English and French took the opportunity to pounce upon the exhausted Germans to wreak an expensive revenge – despite Wilson's protests. Probably no English or French politician who failed to bring home to his people some major exaction of retribution against the Germans would have had a political future. But Wilson had power to use to move things more in the direction he wanted to see them go. But caught up in his utopian world, he failed to see the diplomatic opportunities he actually possessed in order to direct negotiations along the lines he had desired. Wilson was deeply troubled at the

bullying behavior at the peace table of his democratic allies Great

Britain and France – quite in violation of his much-cherished notion

that democracies will automatically behave only in the most enlightened

way. His fellow democracies instead were determined to force crushing

peace terms on Germany and to confiscate the Arab lands of the Ottoman

Turks – very much in violation of the equitable peace terms which

Wilson had announced to lure everyone to the peace table in the first

place. Also, to Wilson's great distress, things were not doing well in Russia – because not blissful democratic peace but instead a violent civil war had accompanied Russia's move to democracy. And this civil war had Russia's democrats lined up on the same side with the old Russian autocrats (the Whites) in a ferocious battle against Marxist-Leninist Communist insurrectionists (the Reds). Wilson's proposed League of Nations

On the other hand, Wilson was able to get his allies at least to accept the fourteenth and final point of his Fourteen Points: the idea of a world assembly (the League of Nations) where he hoped cooler heads could eventually come together once the fever of war had subsided and then reasonably right the wrongs of the abominable peace treaties foisted by the democracies on their defeated enemies. But his plan was greatly foiled by his own United States Senate's refusal to go along with his grand international project, and more importantly, by his own personal intransigence. The extensive commitment required of membership in the League alarmed American senators when Wilson's League of Nations idea was put before them as a treaty requiring senatorial ratification. Senators demanded some compromises that permitted Congress to still control American foreign policy, in particular the Constitutional rule that Congress must be the one, not an international organization, to take America to war. The Senate (whose approval was necessary for all treaties to be fully ratified) was willing to cooperate with this new international government, but with a few key reservations. Wilson's advisors begged Wilson to accept some compromise with Congress concerning these quite reasonable demands. But Wilson was an autocratic purist for whom compromise was an ugly and inadmissible concept. He would have the treaty bringing America into membership in his new international organization only on his terms, and no other. Thus the venture came to nothing in the United States when in late 1919 the Senate failed by only a few votes to ratify the treaty – even while most of the rest of the world went ahead with Wilson's project and joined the League of Nations. Irony of ironies, America was the only nation of note not to join. Wilson incapacitated by a stroke (July 1919)

Not only was treaty ratification crippled by Wilson's intransigence, but so was his health, when during a tour of the country to gain support for ratification of the Versailles Treaty (and thus entrance into the League of Nations) Wilson suffered a crippling stroke. The seriousness of his disability was kept from the American public, who remained unaware during his last two years in office of how feeble Wilson had become (his more ambitious wife basically took care of what little presidential business there was during this time period.) The larger impact on the international status quo

The German sense of betrayal. The betrayal of Wilson's promise of an equitable peace, to which the Germans thought they were agreeing when they laid down their arms, would become the source of German ideological opportunity for Hitler and his Nazis. They skillfully exploited this sense of betrayal (Dolchstoss or Stab in the Back) by the weak new German Weimar Republic, which had agreed to the grand humiliation forced on Germany at Versailles by the so-called democracies. The Nazis played the Dolchstoss idea so effectively that they were eventually able to overthrow the Republic and institute a Neuordnung (New Order) in Germany, one built on German tribal power – not on democratic virtues such as Wilson had believed would soon save the world. They sneered at the weakness of all such democracies and readied themselves to demonstrate exactly what the Neuordnung was to mean to the rest of the world. In short, the peace of 1919 merely set the scene for a return engagement twenty years later of a new round of war: World War Two. Czechoslovakia. In those peace treaties, the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires had large slices of land taken away from them, to be awarded to the newly reconstituted Poland and the newly invented Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. The latter, Czechoslovakia, was founded on an uncomfortable union between the Westward-oriented Czechs or Bohemians and the Eastward-oriented Slovaks – and contained a huge number of Germans along the Czech borders with Germany (Sudetenland). Poland. Poland was restored (after having disappeared previously for a century) out of the territorial loss of Russia, Germany and Austria – with no tradition of democracy to guide it into the new era of "Polish democracy." This reconstituted Poland also contained vast numbers of ethnic Germans – which would make for a very uncomfortable situation facing the new Polish Government, leaving Poland as a vulnerable target should its neighbors recover strength enough to grab back their lost territory (which they would do in 1939 – starting another World War in Europe). Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary was split into two separate nations, losing a lot of territory in the process, and like Germany acquiring democratic governments in order to make them members in good standing of the new democratic world. Yugoslavia. The Serbs, who had been allies of the Big Four, were awarded the central or commanding position in the newly constituted nation of Yugoslavia (South Slavia) – also an uncomfortable union among Serbs, Croats, Slovenians, Bosnians, Albanians and Macedonians. Romania. A large section of Hungary was awarded to another ally, Romania, a recently independent nation split off in 1877 from the Ottoman Turkish Empire; this too would make for a very uncomfortable Romanian union between ethnic Hungarians and ethnic Romanians. Bulgaria. Bulgaria, an Ottoman province until it achieved full independence in 1908, had been an ally of Germany and Austria and thus suffered accordingly with the loss of territory along the strategically vital coast of the Aegean Sea awarded to its newly formed or reformed democratic neighbors. The Turks. The autocracy to suffer undoubtedly the largest territorial and thus political loss was the Turkish Ottoman Empire. This empire had its vast (but quite loose) Middle East Muslim holdings carved up into a number of newly independent nations – leaving the ethnic Turks themselves only a small remnant of an independent state in the center of Asia Minor. Expansion of the English and French empires. The English and French took for themselves big slices of the Ottoman Empire, awarding themselves control over the newly formed Arab states under the Mandate system. The idea of the Mandate system was that these new Arab states were not ready for self-rule – and thus though independent, were to be carefully supervised by the holders of these mandates: Britain and France. Thus it was that Mesopotamia (Iraq), Palestine, and Transjordan were put under the "protection" of the British, and Syria and Lebanon were placed under the French. The Arabs. These new states had some ancient historical claim to political existence, though hardly as true nations. Although mostly Arab in culture, these former provinces of the Ottoman Empire were made up of a mix of various contending Muslim sub-communities and even a mix of ancient Christian communities. They had lived side by side in some degree of peace under the enforcement of the Ottoman Turks. But with the Turkish authority removed these new states were forced to try to find a spirit of national unity on their own – a virtually impossible task. Western imposed democracy instead offered these many sub-communities the opportunity to revive ancient and bitter ethnic rivalries – which only strong-handed monarchies (backed by British or French power) seemed able to bring forcefully to some semblance of national peace. Indeed as democracies, these new states were pure fictions. Germany's loss of its colonies. Germany suffered the loss of its African colonies (Great Britain and France held on to theirs for another forty years), these too being turned over to the English, the French and their Belgian and South African allies – also as "mandates." German colonies in the Pacific were awarded to Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand – and even Japan as mandates. Italy. Italy, for its pitiful contribution to the winning of the Great War for democracy, was awarded German-speaking Austrian lands on the southern side of the Alps (South Tyrol). Russia ... lost in its own civil war. Russia, meanwhile, was plunged into a long and bloody civil war (1918– 1923) between Lenin's Communist Reds and the coalition of Kerensky's and the Tsarists' Whites. Ultimately, more soldiers and civilians died from this civil war than had died during their participation in the Great War. In the end it was Lenin's Communists and the Red Army that won the day in Russia. But interestingly, in finally achieving some degree of control, Lenin backed away from some of his original ideas about moving directly to a Communist economy and society. Instead, with the new Russian or Soviet economy in shambles, Lenin introduced (1921) his New Economic Policy (NEP) allowing small-scale farming and light industry to operate on a moneyed or capitalist basis, which indeed soon brought some stability back to the Russian economy. Moral-spiritual disillusionment among the victors

In general, the victorious democracies – America, Britain, France and Italy – were badly stung by the death and destruction that had ultimately produced no real progress in world civilization. Consequently, the democracies suffered a deep drop in moral nerve after the war. The aggressive instinct that marked the West's presence in the larger world before the war was largely lost, replaced among a number of the West's political leaders by a tired, timid spirit – a spirit which hoped that future conflicts could be avoided by a new attitude of mutual appeasement.

|

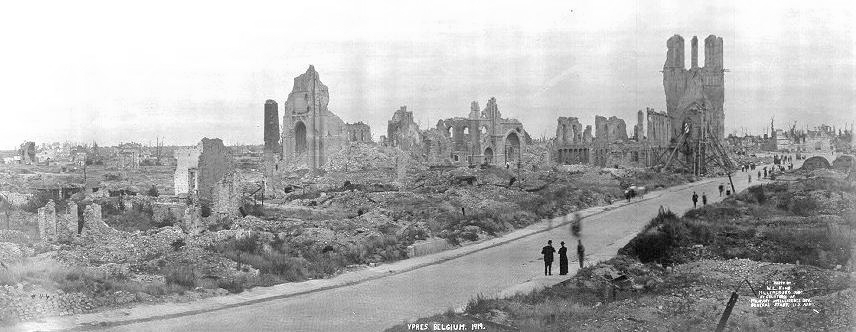

Despite the Armistice or

cease-fire, the Allies are in a deeply angry mood

about all the destruction that the German invasion

has brought

to northern France and Belgium

Ypres, Belgium, after the

Battle of the Lys

Ypres, Belgium, at War's

end – 1919

Passchendaele – before and

after the War

Imperial War

Museum

The Town Square, Arras, France.

February, 1919.

National Archives

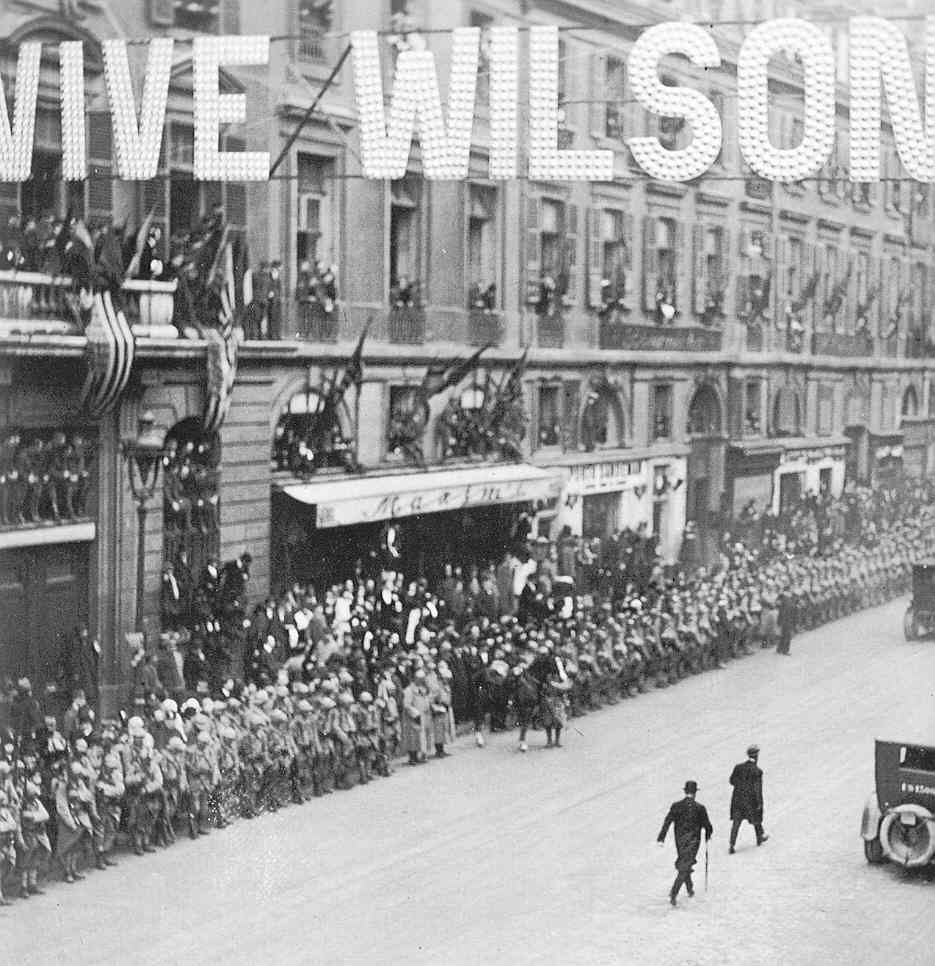

As he heads to Europe, Wilson

has no idea of the difficulties he will be facing to get a "fair"

post-war agreement between

the Allies and the Central Powers at the Paris peace negotiations

Woodrow Wilson leaving for

the Peace Conference in France

Wilson being hailed upon

his arrival in England

National Archives

The Paris crowds waiting

for President Wilson

National Archives

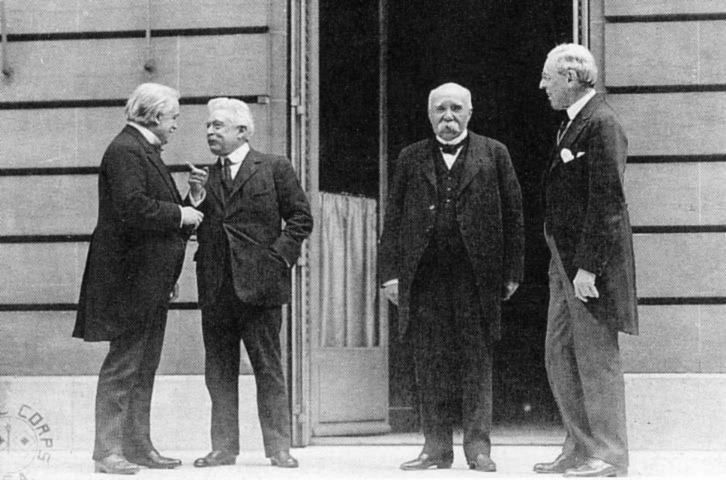

Paris – Wilson and

Poincaré

The Paris "Big Four"

David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow

Wilson

National Archives

Orlando, Lloyd-George,

Clemenceau

and Wilson

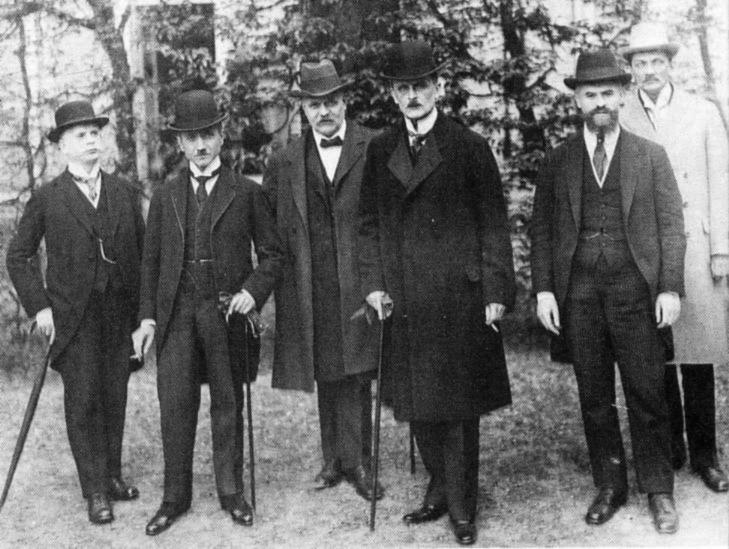

The German delegation at

Versailles – 1919

National Archives

Wilson and the American

Delegation

at Versailles – 1919

The signing of the peace

treaty at the Palace of Versailles

- June 28, 1919

National Archives

The Signing of the Treaty

of Versailles

Spectators craning to see the German signing of the Versailles Treaty – June 28, 1919

|

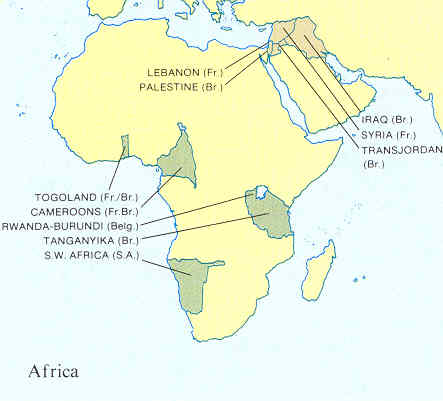

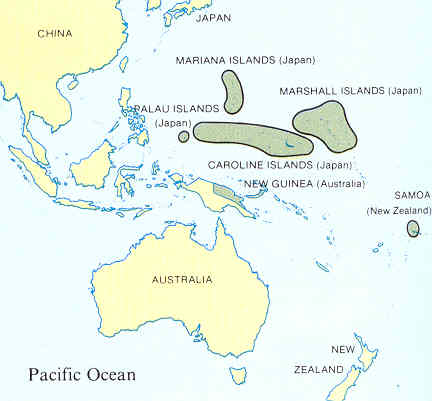

Europe after World War One

- 1923

Stavrianos (1979), p.

127

Fisher, p. 518

German colonial territory

in Africa and the Pacific

and Turkish imperial holdings

in the Middle East

lost after World War

One

Fisher, p. 518

|

|

American

disillusionment

Indeed, America came quickly to the

conclusion that it had been deceived in taking up arms to fight for the

cause of democracy. The results of the peace were not at all what

Wilson had promised that the sacrifices of the war would produce.

Americans quickly became cynical about Wilson's great crusade – and

determined never again to be smooth-talked into getting involved in a

European war.

|

A very hopeful Wilson and

US troops aboard

USS George Washington

returning to the States

- 1919

National Archives

NA-111-SC-61183

"Overseas men welcomed home.

Parade in honor of returned fighters

passing the Public Library,

N.Y. City" – 1919 – photo by Paul Thompson.

National Archives

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

(Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee)

Library of Congress

LC-USZ62-96172

|

Lodge organized the

opposition to Wilson's

cherished League of Nations. Because Wilson would not compromise

with Lodge on some of the principles of the Treaty establishing the League,

it failed narrowly (53-38) to gain the two-thirds Senate vote necessary

for ratification

|

Isolationist Senators William

Borah (R-Idaho) and Hiram Johnson (R-California)

Library of Congress

LC-F81-11547

President Wilson ends his term in the

White House a very sick, very disillusioned man -

and his vision of a new world led by

democratic virtues fades away

Edith Wilson (nee Edith Bolling

and widow of Norman Galt)

Library of Congress

LC-USZ62-70151

|

She held the

office of

President

together during the last year and a half of Wilson's presidential term;

he was too sick to function – a situation known to only a very few people

in the nation at the time.

|

President Woodrow Wilson,

seated at desk with his 2nd wife,

Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, standing at his

side

He was paralyzed on his

left side,

so Edith holds a document steady while he signs – June 1920.

Library of Congress

A very sick Woodrow Wilson

makes

a public appearance on his 65th birthday – 1921

Library of Congress

LC-F8-17266

|

|

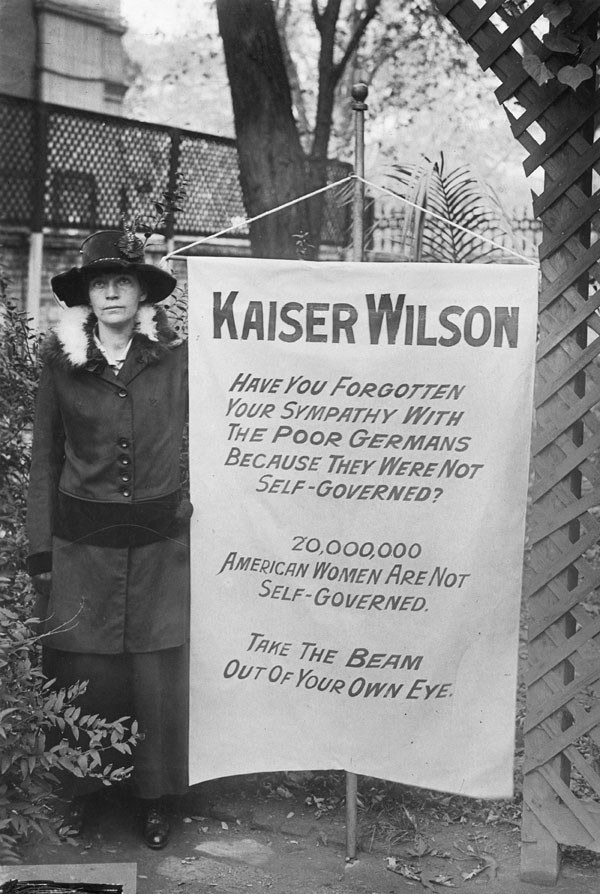

Women’s

suffrage (the right to vote)

had been advanced in the late 1800s as an idea to bring the woman’s motherly

sense of morality to the vices of male politics – an inspired way of reforming

or cleaning up the often sordid business of American boss politics.

Eventually the rationale for women’s suffrage was simply reshaped as a

matter of basic rights, regardless of the moral impact it might or might

not have on American politics. This idea was finally put forward

by Congress as a proposed constitutional amendment in May of 1919 and sent

to the states for ratification.

|

"Suffragette banner. One

of the banners the women who picketed the White House carried"

By an unknown photographer,

Washington, DC, 1918

National Archives

A suffragette protest in

front of the White House, 1918

Library of

Congress

Florence F. Noyes as

"Liberty" in suffrage pageant – 1919

Library of

Congress

Men looking in the window

of the National Anti-Suffrage Association headquarters – 1919

Library of

Congress

The Congressional Resolution

beginning the process of adopting

the 19th Amendment on women's

right to vote – May 19, 1919

Library of

Congress

|

|

Intellectual "Progressivism"

It would be most unfair to blame Wilson entirely for the rise of the kind of "Democratic Idealism" that pushed aside the voices of a wiser and more circumspect political Realism ... a realism that had carefully guided European (and American) diplomacy through most of the previous century. In the first decades of the twentieth century there were other intellectual forces sweeping through the intellectual and cultural centers of Western (and American) society that would challenge that hard-nosed Realism. A growing number of social and political philosophers since the latter part of the 1800s had become convinced that, through some kind of Darwinian process, Western civilization (and, via the West, also world civilization as well) was moving into some kind of bright future in which utopian existence seemed to loom into view. Society just needed some adjustments here and there – led of course by these social and political philosophers – in order to bring this process to completion. For Wilson, of course, that process of adjustment had meant the spread of "Democratic" government to all peoples around the world. But other thinkers had other ideas ... although most of them tracked along similar paths. Historical progress and democracy – however conceived specifically (and the variation was indeed huge) were the bywords, the slogans, the shibboleths, of those who supposed that they possessed special intellectual insights into where the world was headed. |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges