|

|

The decline of moral vision in the nation's

political

leadership The decline of moral vision in the nation's

political

leadership

Coolidge attempts to bring back a sense of the old

Puritan values Coolidge attempts to bring back a sense of the old

Puritan values A few heroes

gave the 1920s a bit of something

higher to hope for A few heroes

gave the 1920s a bit of something

higher to hope for

The 1928 elections offered two quite capable leaders

as U.S. president The 1928 elections offered two quite capable leaders

as U.S. presidentThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 490-496. |

|

|

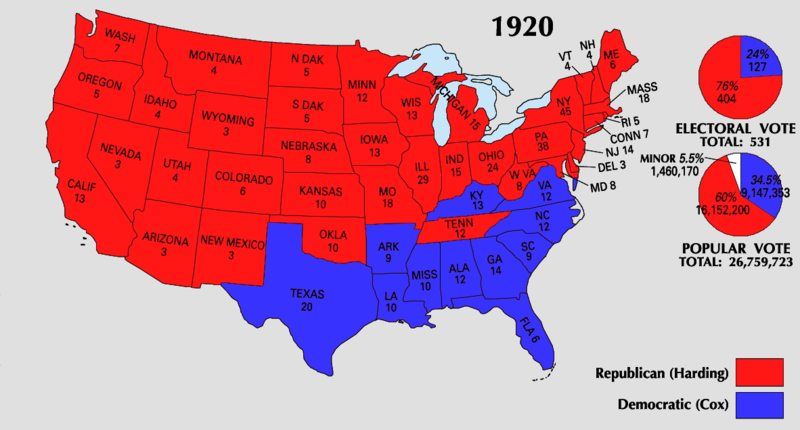

Back in America, the Republicans were deadlocked in their effort to pick a presidential candidate for the upcoming elections of 1920, and finally settled on the supreme nice guy, Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio, as a compromise candidate. He campaigned on the idea that as president he would do everything possible to promote a "return to normalcy" of life in America. With all of the wartime disruption of life and the post war political agitation that seemed to abound everywhere, this idea of a "return to normalcy" was so compelling to the American voter that in the November elections, Harding received a huge 60 percent of the popular vote – against the Democratic candidate James Cox's mere 34 percent of the popular vote, the most lopsided presidential vote in American history. Harding's postwar presidency (1921–1923).

But when it came to the personal behavior of many of these "Ohio Gang" advisors, Harding seemed to exercise little or no control. The results were embarrassing to the president (it would have been even more embarrassing had he lived a few more years to see his friends get what was due them)! In fact, Harding died as a result of a heart attack he experienced following a trip across the country in which he had set out to give answer to the growing rumors about the corruption of his presidential team. One of the most outrageous examples of the corruption of the Harding Administration was the behavior of Harding's secretary of the interior, the elderly Albert Fall. He had secretly leased public oil lands to private companies for his own profit. Most scandalous were the Elk Reserve lease to Edward Doheny and the Teapot Dome Reserve lease to Harry Sinclair, earning Fall $105,000 and $304,000 respectively. This all came to light several years after the end of the Harding Administration as a result of investigations led by Senator Thomas Walsh (Montana). Then there was Harry M. Daugherty, Harding's Attorney General, or top cop, in charge of the Department of Justice. Daugherty earned the nickname "The Fixer" for his role in arranging connections, such as the one that led to the Teapot Dome scandal. But there were others, including the corrupt Assistant Attorney General, Jess Smith, who committed suicide (or was he murdered?) when it was apparent that a Congressional investigation on corruption in the Justice Department was closing in on him (Smith's death occurred just before Harding's ill-fated trip).

|

America votes in a new President,

the Republican Warren G. Harding –

hoping for a "return to normalcy"

Warren G.

Harding

A picnic of President Harding

and industrial notables – at the Firestone estate, 1921

(along the back side of

the table: Firestone, Edison, Harding and Ford)

Warren and Frances Harding

But under President Harding there was a decided lack of moral direction in the nation's top leadership

Harry M. Daugherty, "the Fixer" – Harding's Attorney General

Albert Fall – Harding's Secretary

of the Interior – being helped into court for his trial in 1929.

He had secretly leased public oil lands to private companies – to his own profit. Most scandalous were the Elk Reserve lease to Edward Doheny and the Teapot Dome Reserve lease to Harry Sinclair, earning Fall $105,000 and 304,000 respectively. This all came to light several years after the end of the Harding Administration – as a result of investigations led by Senator Thomas Walsh (Montana). |

Harry F. Sinclair arrives

in Washington. D.C. to begin his jail sentence

The coffin of President Harding

in the East Room of the White House – August 1923

(he died on August 2, 1923

while on a speaking tour to try to boost support for his scandal-ridden

administration)

|

|

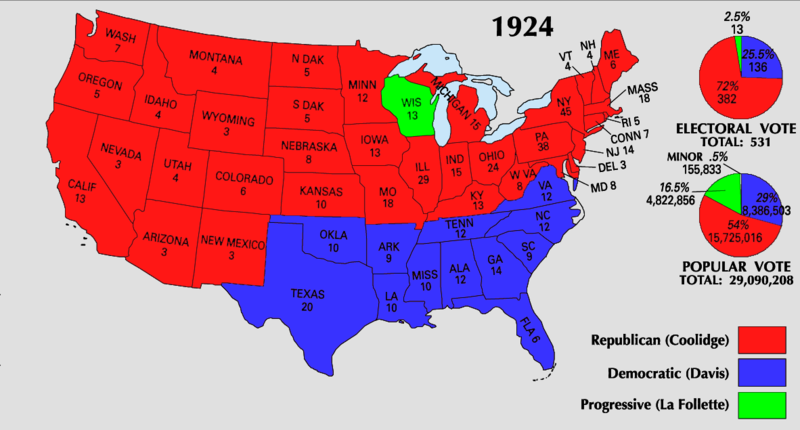

To almost the same extreme that Harding was the picture of loose personal standards, Coolidge was the opposite: the picture of authentic Puritan morality! Coolidge grew up in Vermont, a descendant of a long line of Coolidges who had migrated to Massachusetts with the very first Puritans in 1630, and whose genealogy included officers of the American War of Independence and members of the Vermont House of Representatives. His ancestors tended to be farmers – very active in local politics. Coolidge graduated as an honor student from Amherst College and then went on to clerk and study law in a Massachusetts law firm, eventually being admitted to the bar and setting up his own practice in Northampton, Massachusetts. He married a Vermont school teacher, Grace, and the two of them built a diplomatic marriage, reflective of the quiet and cautious way they both approached life. He soon entered politics and performed decently in the elective offices he pursued, first as representative to the Massachusetts state assembly (the General Court), then as mayor of Northampton, then as state Senator, where he became noted for his moderately progressive positions on a number of issues. In 1915 he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts and then in 1918 the state's Governor. He conducted himself as a moderate-progressive, and a reluctant spender of the state treasury – nothing that would have brought any particular notice to him nationally. What brought him to national attention was the 1919 Boston police strike over the issue of a police union, pitting the state against the rising power of the labor unions. Coolidge took a strong position in support of the Boston mayor, calling out the national guard and answering the union that "there is no right to strike against the public safety by anyone, anywhere, any time." That indeed brought Coolidge national attention, at a time that America was undergoing a serious Red Scare. And thus it was that in the Republican National Convention in which Harding was nominated as the party's presidential candidate, Coolidge was chosen as Harding's vice-presidential running mate. And from there – with Harding's unexpected death in 1923 – Coolidge found himself in the White House as the nation's president. As president his attitude conformed nicely to the old adage: "the government that governs least governs best." Although Coolidge was deeply supportive of civil rights for Blacks (speaking out on their behalf in a time of extensive KKK activity across the nation, and appointing them to Federal positions) and Indians (pushing for full American citizenship of all American Indians), when it came to government programs and spending he was strongly opposed. He worked to cut back federal spending and move the budget to a balance instead of a spending deficit. As far as he was concerned the business of business was not the business of the government, but instead a matter of the private or capitalist sector (which was doing quite well during his presidency). In 1924 he was returned to the White House on his own merits. He did quite well in the vote despite his very low-key candidacy (low key in great part due to the death of his sixteen-year-old son that July) and despite a third-party run of Progressive politician La Follette, which the Democratic Party opposition hoped would split the Republican vote and give the Democrats the victory – much as Teddy Roosevelt's third-party run opened the way for the Democratic candidate Wilson to gain the presidency in 1912 on a mere plurality rather than a clear majority of the votes. But given the hugely upbeat mood of the country during the Roaring Twenties, Coolidge actually received 54 percent of the popular vote and 72 percent of the electoral vote. He finished out his four years in office with no major programs of note (he believed that those matters belonged to the states, not the federal government) and no scandals. As there were no major foreign policy issues burning at the time, American foreign policy during his presidency was also quite low key. But that was the way Americans wanted things. They had other things personally to focus on, like getting rich fast. And in 1928, as his term approached a close, Coolidge made it clear that he would not take on another term, although many expected him to do so. He was tired and ready to go home. Little did he know that by doing so he saved himself from being the one identified as "responsible" for the country’s economic catastrophe, the Great Depression.

|

Calvin

Coolidge – Governor

of Massachusetts with called-up National Guardsmen – 1919

| ... in a delayed response (a full two days of a breakdown of law and order) to a strike of the Boston police. Though the Boston mayor was the one who brought the city under control,Coolidge got credit for breaking the strike with his response to Samuel Gompers concerning the crisis: "There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time." This well-publicized line got him the nomination as Vice President on Harding's national Republican ticket. |

Vice

President

and Mrs. Coolidge

- 1921

The

Presidential Election

of 1924

Coolidge

delivering his inauguration

address – 1925

Calvin

Coolidge arrives to

dedicate a park in Hammond, Indiana – June 14, 1927

|

There was Charles Lindbergh –

the picture

of traditional American virtues of bravery and simplicity

Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974)

and his plane, Spirit of St. Louis

preparing

for his flight non-stop from Long Island, New York, to Paris, France

Charles Lindbergh (25) and

the Spirit of St. Louis

Lindbergh lands at Le Bourget

airfield in Paris – May 21, 1927

English crowds rushing to

greet Charles Lindbergh on his return from France -

after his trans-Atlantic

flight of May 20-21, 1927

Charles Lindbergh's ticker-tape

parade on Wall Street – 1927

Charles Lindbergh in a ticker tape parade through New York City

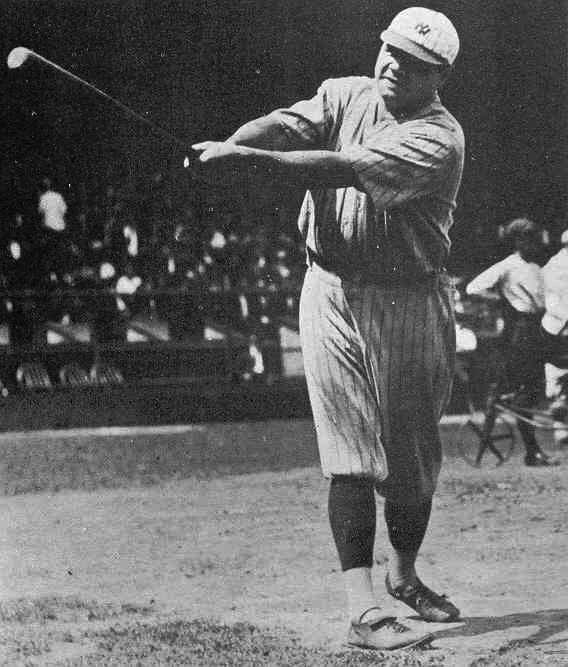

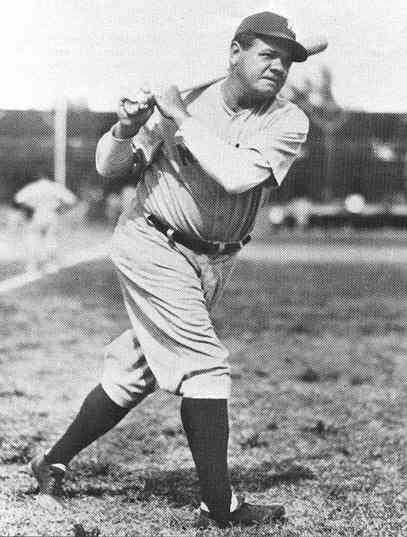

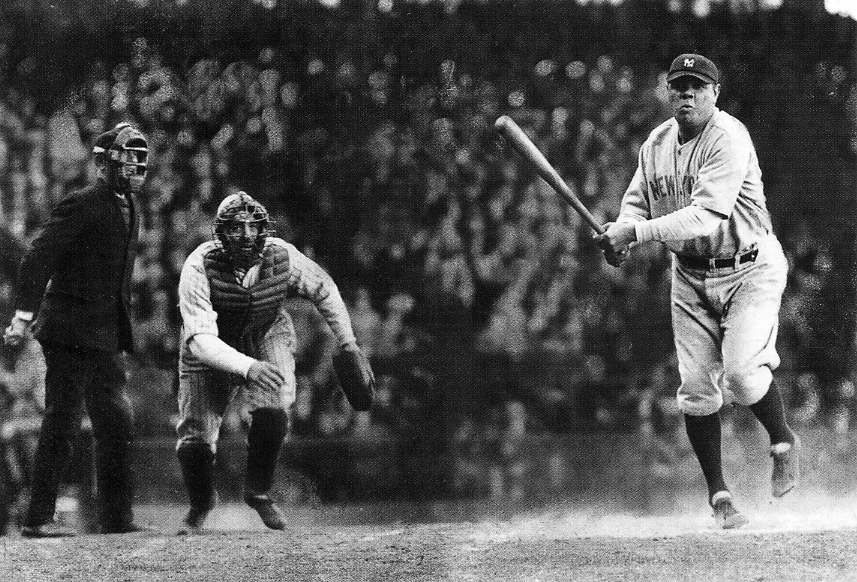

And there was the "Sultan of Swat," Babe Ruth

Babe Ruth – "Sultan of Swat"

- 1920s

Babe Ruth – Sultan of

Swat

Babe Ruth hitting another

homer (60 alone in 1927)

(he helped to restore the

sport to popularity after the 1919 Black Sox scandal)

Quarterback Red Grange (with

football) of the Chicago Bears helping to strengthen the NFL

|

|

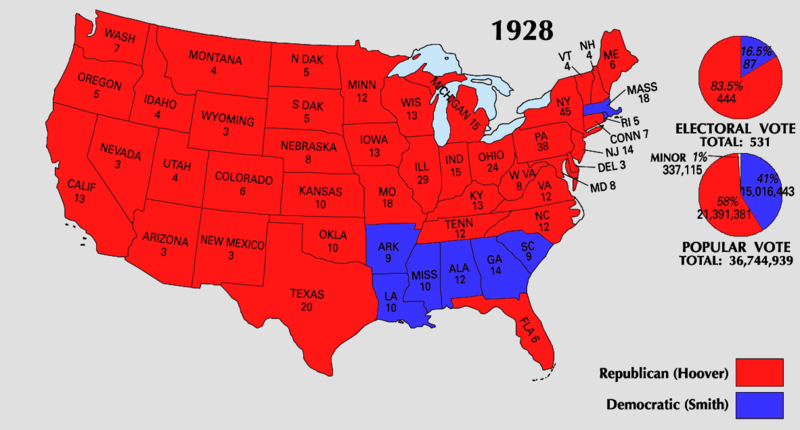

Herbert Hoover (U.S. president 1929-1933)

Hoover was born in 1874 to a Quaker family in Iowa, his father dying when he was six and then his mother a few years later – leaving him and an older brother and younger sister orphans at a very early age. After changing hands among relatives, he finally ended up in the care of an uncle living in Oregon, settling in to work for his uncle and attend night school. At 17 he entered with the first class of the new Stanford University in California where he majored in geology. After graduation from Stanford in 1895, he went to work for a mining engineering firm in California, moving two years later to work in the goldfields of Western Australia. Desert conditions there were harsh, but he worked hard and soon became a very young manager of a gold mine. Rivalry between himself and a higher official in the company led Hoover to move his operations to China (in 1899 marrying a Stanford college sweetheart, Lou, along the way), where he became the chief engineer for the Chinese Bureau of Mines and general manager of the Chinese Engineering and Mining Corporation. Along with his rise in professional importance he seemed to pay close attention to the status of his workers, whether the Italians who were brought in to work under him in Australia or the Chinese who worked for him. He (and also his wife) would always have a strong humanitarian interest accompanying his extensive work in the mining profession. He and his wife Lou held their own in Tianjin during a month-long siege (1900), part of the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, but soon after it was put down opened new operations in Australia (1901). At this point he became part owner of the gold mining company that was responsible for half the gold production in Australia, and thus found himself at a very early age on his way to enormous personal wealth. Soon his operations expanded to South African gold mines, to Burmese silver mines, to Russian copper mines, and now also to Australian zinc mining. By 1908 he had established his own mining consultancy business, traveling the world from his offices in San Francisco, New York City, London, Paris and St. Petersburg (Russia). He soon found himself lecturing at various universities and writing what quickly became standard texts in his field of metallurgical engineering. With the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Hoover put aside his work to focus on getting Americans trapped in Europe back to the States, covering their travel expenses in the process. This was the beginning of the turn of his primary interest away from making money, to organizing operations (and money) needed to help people hurt by the ravages of the war that now consumed the Europeans. Basically, he undertook to feed the Belgian population, whose economy was devastated by the war. He did this for the next two years, heading up the Commission for Relief in Belgium, negotiating the arrangement with the German, Belgian, Dutch, French and British governments in order to be able to import massive amounts of food – and make sure it got delivered to the Belgian civilian population (over ten million individuals per day at the height of its operations) rather than the German troops occupying Belgium. Then with the entry of the U.S. in the

war his position as a neutral was ended and he returned to the States,

newly appointed by President Wilson to head up the U.S. Food

Administration, to avoid having to put the nation on rationing but

nonetheless some kind of discipline in order to bring food to the

American troops serving in Europe. In the meantime, Hoover had not lost his interest in scholarship and left a huge endowment to his alma mater, Stanford, for the purpose of gathering important documents relating to the war. This effort led to the founding of the Hoover War Library, subsequently known as the Hoover Institution. Now the 1920 presidential election was coming up, and Hoover announced himself as a candidate – with the Republican Party. But he did not do well early in the primaries and thus did not impress the national party greatly, which instead turned to Harding as its candidate. But Hoover supported the choice, Harding was elected, and Hoover was then asked by Harding to be his secretary of commerce (a fairly new cabinet position, whose exact function was not yet well established). As secretary of commerce, Hoover went about organizing the operations of the department of commerce, finding new areas of responsibility for the department in – as he understood matters – improving the efficiency of the American economy. This of course put his hands in a wide range of government activity, so much so that at times (given the general restraint of the Republicans with their narrow view of the responsibilities of the federal government) Hoover seemed to be more central to governmental matters than the president! His goal was not to fight American industry (as trust-busting Progressives tended to do) but to work in close association with that industry, in order to get the very best out of it – with his activities in the field of electrical power generation, rural water management (and flood control), automobile and highway safety, aviation, radio broadcasting, and a sincere concern for the lives of sharecroppers, especially Black sharecroppers. Sensing in 1928 that he now had a better chance at the U.S. presidency (Coolidge had announced that he would not run again), Hoover once again announced his candidacy, this time his wide popularity opening the door to the candidacy quite easily. And in the general election that November he easily carried both the popular vote – 58 percent against his Democratic Party opponent, the Roman Catholic and "wet" New Yorker (strongly opposed to the 18th Amendment prohibiting the consumption of alcohol), Al Smith with only 41 percent – and 444 electoral votes to Smith's 87 electoral votes. Thus when Hoover took office in 1929, America was expecting to see the fabulous economic journey that the country found itself embarked on expanded even more. Little did the country realize that the very opposite was soon to occur. But in any case, that's how the country finished out the Roaring Twenties politically.

|

Al Smith – Democratic nominee

for the Presidency in 1928.

He was Catholic, big-city

and "wet" (anti-prohibition).

He lost to Hoover – but

not nearly as badly as the Democrats had done in 1920 and 1924.

He began the refashioning

of the Democratic Party through a strange marriage between

the northern urban and southern

populist voter

Herbert Hoover – heading

up the Committee for Relief in Belgium – 1915-1918

An amazingly talented and

philanthropic individual, he prospered greatly as a mining

engineer and gained respect as one

dedicated to helping the poor and hungry.

His volunteer work in Belgium

and France saved countless thousands

from starvation during and

after World War One

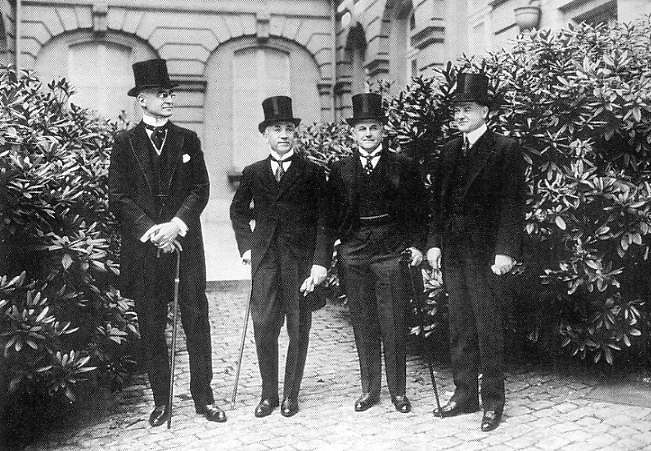

Hoover (right) with Bernard

Baruch, Vance McCormick and Norman Davis

in Brussels – 1919

... attempting to help rebuild

war-torn Europe

Hoover, as Secretary of

Commerce,

investigating radio signaling.

He helped establish minimum

safety and performance standards in US industry.

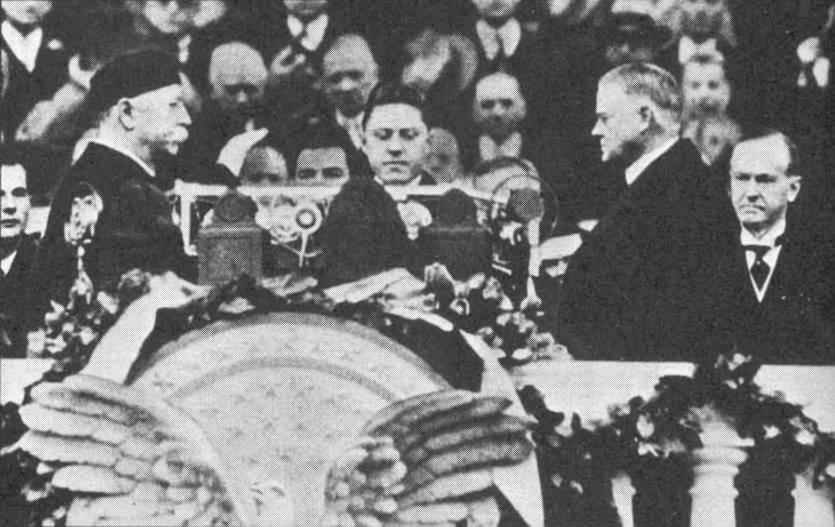

Hoover's inauguration – March

4, 1929

(the start of the Great

Depression was only 7 months away)

Herbert Hoover – President 1929-1933 – by Douglas Chandor

Hoover, in the years following

the end of World War Two, again served as philanthropist:

he raised $325 million to

help ward off the horror of starvation among Europe's children

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges