|

|

Hoover's indecision Hoover's indecision The spiral downward of the

American economy The spiral downward of the

American economy America and the

world during the Hoover

Administration America and the

world during the Hoover

Administration The Bonus Army

incident The Bonus Army

incident The 1932

presidential election The 1932

presidential election Roosevelt: The story behind

the

man Roosevelt: The story behind

the

man The Depression has

deepened as Roosevelt

enters the White House The Depression has

deepened as Roosevelt

enters the White House Roosevelt quickly sets out to institute a "New Deal" for

America Roosevelt quickly sets out to institute a "New Deal" for

America The Supreme Court shoots

down FDR's New Deal programs The Supreme Court shoots

down FDR's New Deal programs Persistent

drought

creates the Midwest "Dust Bowl" Persistent

drought

creates the Midwest "Dust Bowl" Migration West to California takes up

in

earnest Migration West to California takes up

in

earnest Poverty remains a

serious problem throughout the 1930s Poverty remains a

serious problem throughout the 1930s "Roosevelt's New

Deal

brought us out of the Depression" ... yes or no? "Roosevelt's New

Deal

brought us out of the Depression" ... yes or no?The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 507-522. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

The October 1929 crash occurred during the first year of the presidency of the Republican Herbert Hoover, the famous philanthropist who at the end of the Great War had organized a huge relief effort for the starving people of war-torn Belgium. Now it was his turn to do something about a worsening economic picture in America. In the face of this massive shock to the American stock market, Hoover tended to follow the common wisdom of the Republican Party (which had long dominated American politics) which was simply to follow the central principle of capitalism and let the market correct itself; it was not the government's job to meddle with the nation's economy.

|

A very wearied President

Hoover at a gridiron dinner – March 1932

|

Hoover looked especially to his Secretary of the Treasury Mellon for encouragement and advice. But Mellon's approach to the depression was not only Republican but even rather Darwinian: government should not intervene, but instead allow a natural liquidation or shake out of weak or poor business factors (notably labor, farmers, and small businesses) in the market mechanism. But ultimately this philosophy helped no one, not even the big capitalists who depended on an affluent society to sell their products to. Enforced poverty helped no one. The economy worsened. Eventually Mellon was dismissed by Hoover – though only when his failure to pay federal income taxes was discovered. |

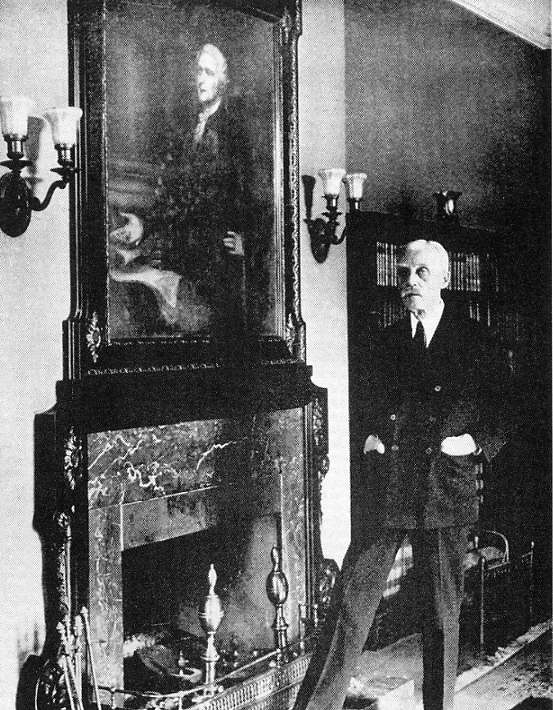

Hoover's

Treasury Secretary,

Andrew Mellon

|

Some of the 6,000 men who

queued up for jobs offered by a New York employment agency – 1930

(135 found jobs; by 1932

almost 30% of the American workforce was unemployed)

A Brooklyn family evicted

from their apartment

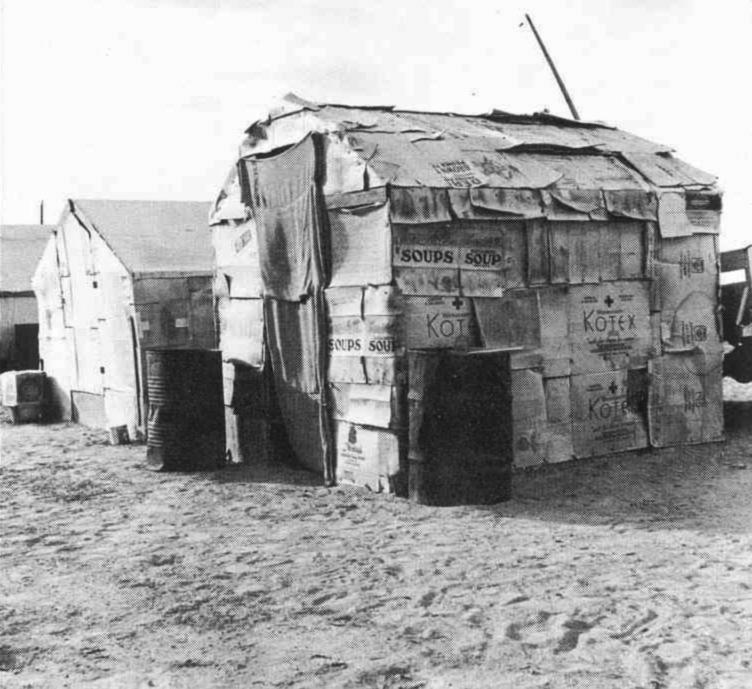

Shacks of the Seattle's "Hooverville"

A typical "Hooverville" shack built during the Depression around cities with high unemployment

As

1930 turned

into 1931, and 1931 into 1932, the economy only worsened

|

Belated government efforts to support the economy

Finally and belatedly, as the economy continued to fail to revive (one fourth of American workers were unemployed), Hoover began to propose government measures to try to help out the worst parts of the economy. The 1932 Emergency Relief and Construction Act attempted to start up public works programs to put the unemployed to work and to provide government-secured capital to help start up industries. But these measures came too late to swing the country back in support of Hoover's presidency. Besides, the Democrats smelled political victory in the November 1932 elections and were not in a mood to be very cooperative with the Hoover presidency, which they were pleased to blame as the cause of the Depression.

|

|

|

Foolish trade barriers Congress at one point attempted to help the economy – through the erecting of a new trade barrier (the infamous Hawley Smoot Tariff) designed to protect struggling American producers. But it only made the situation far worse. It stirred up a trade war with America's trade partners – who in retaliation against American protectionism moved to protect their own industries from American competition. Ultimately this merely helped to pass the depression on to the rest of the Western world.

|

Otherwise, America's foreign policy was one

basically

of isolationism

– except within its own Western Hemisphere where it continues its

economic

overlordship

Henry Stimson, Hoover's

Secretary

of State – 1931

(he eventually became a

believer in non-intervention in Latin American affairs)

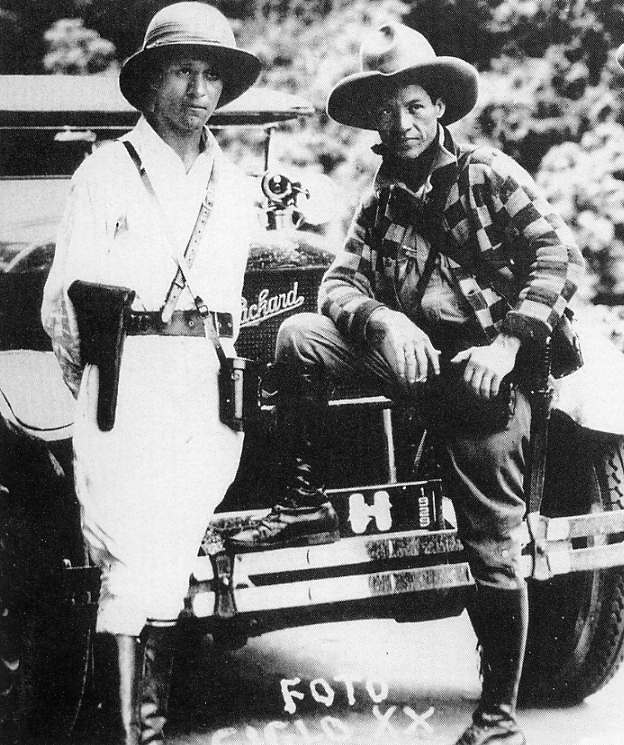

One of the biggest issues

of the times was the anti-capitalist / anti-American

uprising in Nicaragua led

by the charismatic Augusto Sandino

| Over a period of six years he attacked American military forces in his country – until their removal in 1933. He then retreated from public view – but was murdered the following year under the orders of the commander of the National Guard, Anastasio Somoza – who soon maneuvered himself into position as Nicaraguan dictator. |

Nicaraguan rebel leader Augusto

Sandino – [right] enroute to Mexico. June 1929

National Archives

NA-127-N-522050

"One of our speed cars mounted

with Heavy Browning Machine Guns

to offset any possibility

of rioting during the 1932 Presidential Elections

in Nicaragua." photo by

Capt Charles Davis.

National Archives

Sandino's Flag – Nicaragua

- 1932

|

|

One sad incident that happened toward the end of Hoover's presidency was the march on Washington of the Bonus Army in the summer of 1932. The marchers came to Washington, D.C., to demand their veterans' bonus payments early from Congress, a bonus that had been promised them for their service in the Great War. But the payments were not due to begin until 1945. The veterans wanted them now – even if it meant they would be receiving these bonuses at a lower rate. They and their families needed the money now in order to survive. After several months of camping near the Anacostia River, and after several confrontations with police, federal troops (commanded by Douglas MacArthur and his staff assistant Dwight D. Eisenhower, aided by George Patton), upon orders by Hoover, drove the marchers from the city. The roughness of the police and troops on these war veterans shocked the nation – and further alienated the people from the Hoover administration.

|

Some of the 17,000 members

of the "Bonus Army"

who had descended on Washington,

D.C. in mid 1932

vowing not to leave until

the bonus promised them for service during the War was paid.

"Bonus Army" encampment in Washington, D.C. – 1932..

"Bonus Marchers" and

police

battle in Washington, DC.

National Archives

General Douglas MacArthur

conferring with his aide, Major Dwight D. Eisenhower

about plans for evicting

the Bonus Army from Washington, D.C. – 1932

General MacArthur and Major

Dwight Eisenhower in uniform

prior to the forceable dispersing

of the Bonus Army – 1932

Federal troops tear-gassing the Bonus Army – July 1932

|

|

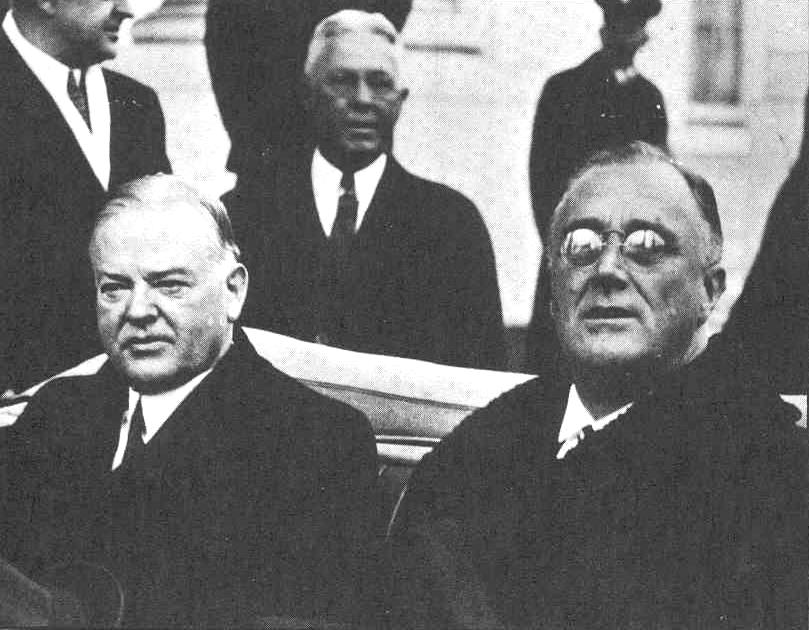

General disillusionment with the Republican Old Guard

politicians paved the way for Franklin D. Roosevelt to gain a grand victory in the 1932

elections Hoover was an easy target for his opponent, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the 1932 presidential race. Roosevelt took Hoover to task for his many failures as president in dealing with this national crisis. Ironically one of his favorite lines of attack during the campaign was Hoover's extravagant spending in order to buy the country out of the economic crisis – and how Hoover wanted to turn Washington into the control center of the American economy. Roosevelt's Vice-presidential running mate, Nance Garner, even accused Hoover of advancing the cause of Socialism in America. How ironic, for the incoming Roosevelt Administration would not only undertake exactly these same kind of Washington-directed measures – but would do so in massive proportion! Blaming

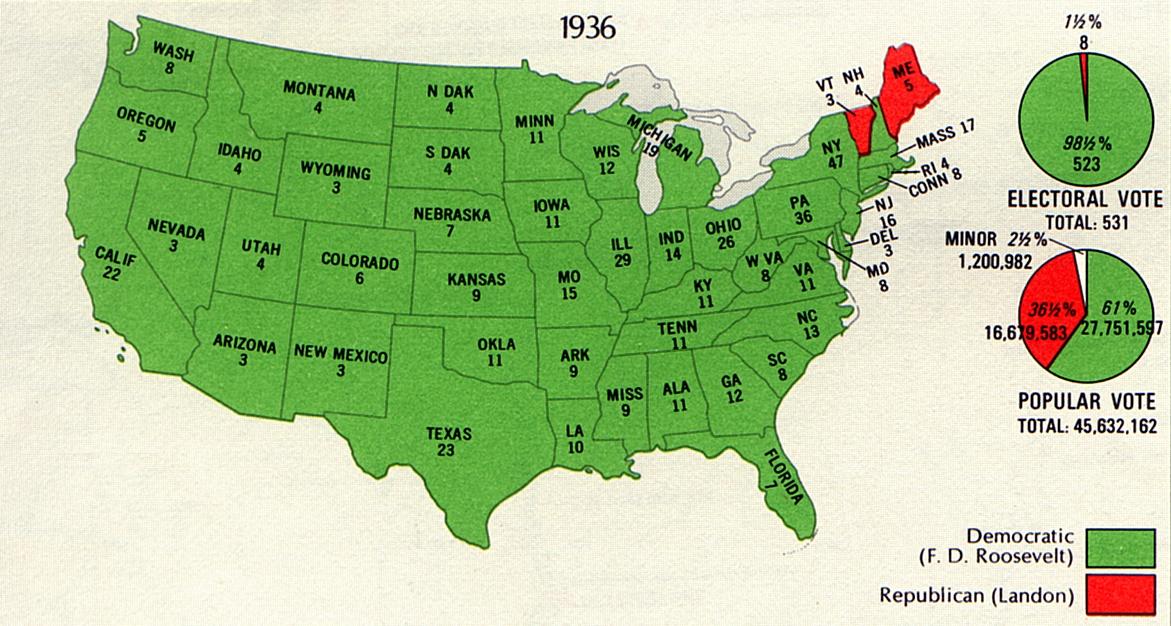

Capitalism for the Depression No one really understood the actual dynamic that had caused the Depression: the fanciful belief that reached down to very ordinary Americans that somehow the fast path to wealth offered through Wall Street investment was destined to go on forever and the presumption that the hot consumer market that kept millions employed was also a permanent feature of American life. The 1920s economy was all so new that there was bound to be little perspective available to the average American as to how economics actually worked. And when the dream came crashing down, confusion, then bitterness, naturally took over. Worse, Americans grasped ahold of easy explanations, simple portrayals of evil behind this whole catastrophe. And history reveals that there is nothing uglier to behold than a society's treatment of a respected prophet, whose prophecies have failed to come to pass. And in the case of early 1930s America those failed prophets would be the capitalists, once worshiped as gods, and now despised as the very devils themselves. And Roosevelt picked up on this opportunity to use exactly just that imagery in this run against the heavily pro-capitalist Republican Party. Using Christian religious imagery quite familiar to the American people, in his acceptance speech as the Democratic Party's presidential candidate he blamed the depression on those among the American people who had "made obeisance to Mammon" (worshiped wealth and the providers of just such wealth). This attack on the prophets of capitalism played well, for to the average American it was the only thing that made sense as they faced a surrounding world of economic disaster. The capitalists themselves had caused this through their own greediness. What Americans now needed was a nation run by compassion, directed not by capitalism but by a government in Washington sensitive to the needs of the people. And Roosevelt promised to be exactly that sensitive caretaker if elected. During his campaign he regularly employed Christian ideals and language that had been at the heart of the older Social Gospel, promising the people in so many words that the Democratic party would do the "Christian thing," unlike the insensitive pro-capitalist Republicans. And of course the tactic worked beautifully, because the Republicans had no countering ideas to offer. Clearly the god Capitalism had failed. The November elections were extremely sad for Hoover and elating for Roosevelt. Roosevelt had received 57.4 percent of the popular vote to only 39.7 percent for Hoover. And the electoral vote went 472 for Roosevelt and 52 for Hoover. And just to drive home this anti-capitalist message, in his inauguration address delivered in early 1933, he not only issued his famous "firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is, fear itself" he went on to attack the legacy that greedy capitalism had left Americans with. Again, using familiar Christian terminology to bash the greedy agents of capitalism, whom he referred to as "the money changers," he stated: ...rulers of the exchange of mankind's goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and have abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men.His promise to the American people was that his administration would now take over the matter, and undertake action, such as capitalism had failed to do in the face of this national tragedy. I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken Nation in the midst of a stricken world may require. These measures, or such other measures as the Congress may build out of its experience and wisdom, I shall seek, within my constitutional authority, to bring to speedy adoption.And thus it was that Americans now hungrily looked to Washington – not Wall Street – to move their lives forward. None dared call this Socialism (except a group of Humanists that year who were proud to do so) because in a still highly individualistic America, Socialism remained largely a taboo concept. Thus the Roosevelt program was never assigned any other label except "New Deal," although Roosevelt's actions would come to look amazingly like that which was going on in a number of European countries faced with the same problem. Many Americans were quick to point this out. But it was not wise to speak out too much about what was happening to an American society increasingly dependent on the good intentions of political authorities gathered in Washington. The election had made it quite clear: the majority of the Americans had just given Roosevelt full authorization to fix the problem any way he saw fit to do so. Roosevelt the Christian

It is important to note however that behind this carefully chosen anti-capitalist political stance there existed a very strong personal faith that moved Roosevelt, one which actually guided him very strongly as he made his way through the challenges before him. He had been raised a believing Episcopalian and had been directed in key times of his life by strong Christian counsel, and called on that faith when he was stricken in the prime of his professional life by crippling polio. But he was an overcomer by character, amazingly confident that all challenges could be met simply by seeking to do the right thing. He believed strongly in a God of justice and fairness, and a sense that despite – or even because of – his crippling affliction he had been chosen by God to show the world how to overcome life's worst challenges. He was therefore incredibly optimistic, a personal trait that would attract many to this man of enormous moral and spiritual strength, including a nation that would somehow have to keep moving forward even in the darkest of times. That was his understanding of his Christian faith, a matter of enormous importance to him, and as he saw it, to America and the world as well. |

FDR stumping along the Jersey

shore – 1932

Roosevelt meets

farmers

FDR whistle-stopping in

Goodland,

Kansas – 1932

He promised a "New Deal"

- and the repeal of the 18th Amendment on Prohibition

Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers

a speech in New Albany, IN,

during the 1932 Presidential

campaign

1932 Democratic Presidential

nominee Franklin Delano Roosevelt

and VP nominee John Nance

Garner

FDR, with his son James, being introduced by the comedian Will Rogers – 1932

The presidential election

of 1932

Hoover and Roosevelt on the

latter's inauguration day – 1933

Franklin Roosevelt delivers

his inaugural address, March 4, 1933

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1933

|

|

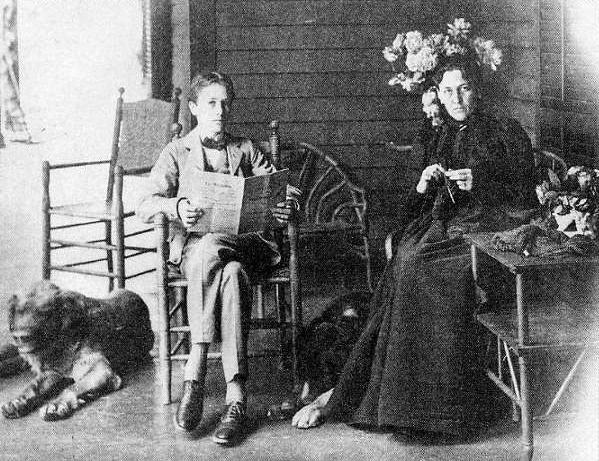

The making of the president

Roosevelt was born in 1882 in the Hudson River Valley town of Hyde Park to a very prominent New York family, was raised as an only child in considerable privilege, and was watched over carefully by a doting mother, Sara. Sara, who was of Massachusetts stock, directed him to spend his summers in her home state (when not in Europe, which the family also visited every year) and had him enrolled in the prestigious Groton Academy in northern Massachusetts. Most significantly, here under the direction of the Episcopal priest and school headmaster Endicott Peabody,1 he was taught the importance of those raised to privilege in developing a commitment to public service – but also the importance of a strong Christian sense of responsibility toward those less fortunate than they. This effort of Peabody's would not be lost on Roosevelt. As was generally expected of a Groton boy, he then went on to study at Harvard, where he continued his standing as an average student. But while at Harvard he began to develop political ambitions, particularly with his uncle Theodore (Teddy Roosevelt) becoming U.S. president at that time. He now had a political role model to follow – however as a Democrat, unlike his Republican uncle (nearly all those around him, even since he had entered Groton, were also Republicans). With the death of his father James at the

end of 1900, Roosevelt's mother Sara became even more directly engaged

in her son's life (she had even followed him to Boston when he was at

Harvard). But Franklin finally found that a relationship which

developed in 1902 with Eleanor Roosevelt (Teddy's niece and thus a

distant cousin of Franklin's) allowed him to free himself considerably

from his mother's domineering ways (Sara was very opposed to Franklin's

and Eleanor's relationship). His marriage with Eleanor was not an easy one for either of the two. They had six children in fairly short order between 1906 and 1916, although the third child died soon after birth. They both took the child's death very hard. Also in moving after their marriage to the Roosevelt estate (Springwood), Sara moved in with them, a constant source of irritation for Eleanor. Also, Franklin had a fascination with a number of other women, producing scandals – especially his affair with Eleanor's social secretary, Lucy Mercer. Divorce was considered – but Lucy was not interested in a marriage with Franklin (too many complications). His marriage with Eleanor thus somehow survived, after he promised not ever to see Lucy again (a promise he did not keep). But it was a cold marriage, mostly thereafter just an arrangement of some small degree of social and political convenience. Eleanor found herself busied elsewhere with a number of social causes that kept her away from her husband. In 1910 Roosevelt ran for the position as New York State senator, the local Democrat Party glad to have a Roosevelt name to put forward in a district that had been solidly Republican since before the Civil War, and shocked when he was actually elected to the position. In the New York Senate he found himself in opposition to the New York Tammany Hall political machine, and consequently developed considerable experience in the art of political maneuvering – which helped him be reelected to the Senate position in 1912 as something of a distinct social reformer or progressivist. But that same year he had also thrown personal support to the reformist Democratic Party presidential candidate, Woodrow Wilson (who also was running against Franklin's uncle), earning Franklin a cabinet appointment as the assistant secretary of the navy – a position he would hold for the next seven years, (ironically, the same position that also his uncle had held in the early years of his national political career). Also, like his uncle, the younger Roosevelt actually had long been interested in naval affairs, was very well read-up on the subject, and was fully capable of being an excellent contributor to American naval policy. He would continue to serve in this capacity through the years of the Great War. In 1920, the Democratic National Convention picked Roosevelt, only thirty-eight at the time, to run as the party's vice-presidential candidate, serving alongside the party's presidential candidate, Ohio Governor James Cox. But the election turned into a landslide for the Republican ticket of Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. After the election Roosevelt returned to his law practice in New York. But tragedy struck in August of the next year (1921). He contracted polio while vacationing at Campobello Island in Canada, the polio leaving him permanently paralyzed from the waist down. A man of iron will, he refused to admit defeat by the disease and maintained his law practice, while at the same time attempting various therapies. In 1926 he purchased a resort at Warm Spring, Georgia, not only for his own treatment, but for others also afflicted with the disease. His disease in fact had become for him something of a cause, and two years later he created the organization that would eventually become the famous March of Dimes, dedicated to fighting the scourge of polio. He also developed immense upper body strength and the ability to walk (short distances) with the aid of iron braces, often also leaning on the arms of an assistant – so as not to have to appear in public in a wheelchair. In the meantime, he kept up with New York Democratic Party politics, improving his relations with Tammany Hall, and supporting Alfred E. Smith in the New York race for governor in 1922 and again in 1924 (which Smith won), then for U.S. president in 1928 (which Smith lost). At the same time Smith encouraged and supported Roosevelt's candidacy for New York governor in 1928, which Roosevelt won (twice) making him the state's governor from 1929 to 1932, when he chose to run for the U.S. presidency. And in 1932, with the country caught in the depths of the Great Depression his win over his Republican opponent Hoover (naturally blamed for the tragedy) was fairly easy: Roosevelt was elected to the U.S. presidency with one of America's widest margins of victory (14 percent) over his Republican opponent. 1Roosevelt became very close to Peabody, having him preside at his wedding with Eleanor and at the weddings of his children.

|

A young FDR and his mother

Sara

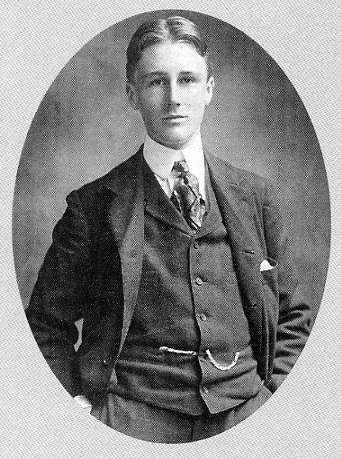

FDR as a last-year student

at Groton at age 18

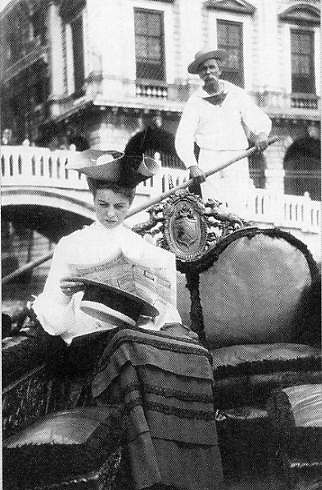

Eleanor Roosevelt in

Venice

Asst. Secretary of the Navy

Roosevelt exhorting the crowd to buy Victory Loan bonds – 1919

Democrat Vice-Presidential candidate FDR

with Presidential candidate

3-term Ohio Governor James Cox – 1920

Polio-stricken FDR being

helped from a car

(he contracted the debilitating

disease in 1921 at age 39 – but generally hid it from public view)

|

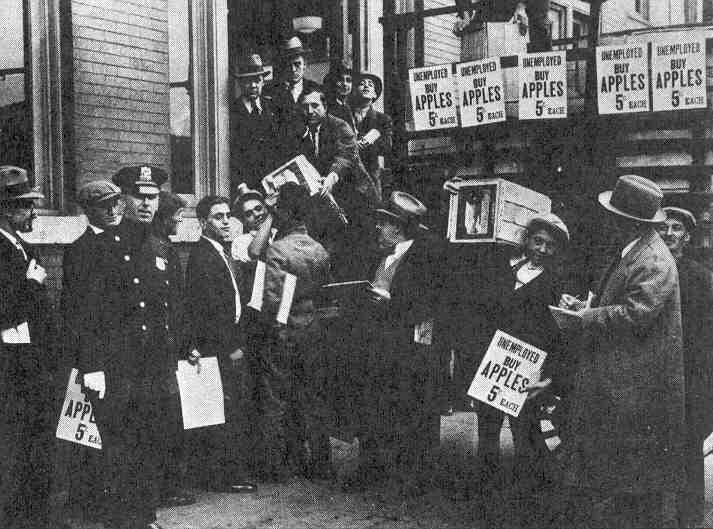

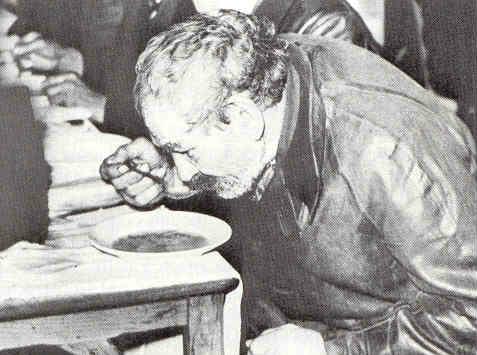

Selling apples

Distributing apples for the unemployed to sell on street corners

Land auction – Spotsylvania,

Virginia -

1933

Unemployed Americans lining

up for relief assistance

Soup and Bread Line

"White Angel

Breadline"

relief in a soup

kitchen

Bread and canned goods being

distributed by St. Peter's Mission in New York City

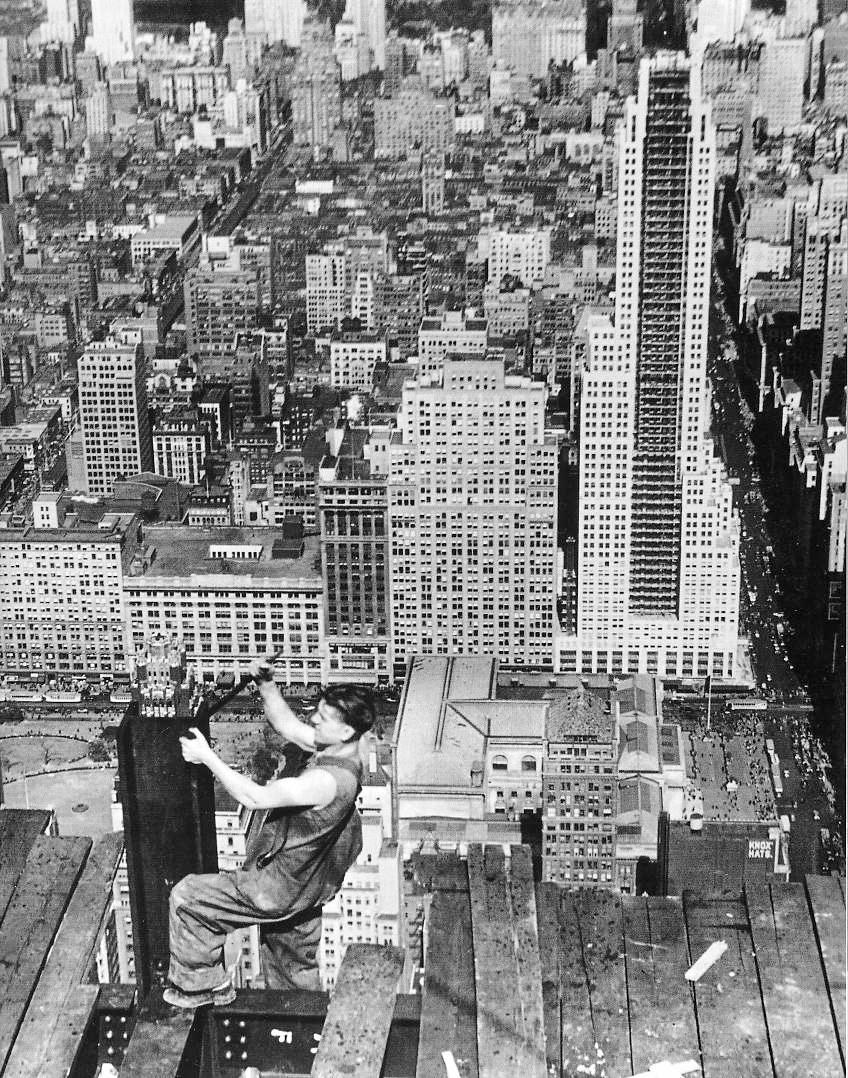

Some economic life does move forward in America during the 1930s despite the tough times

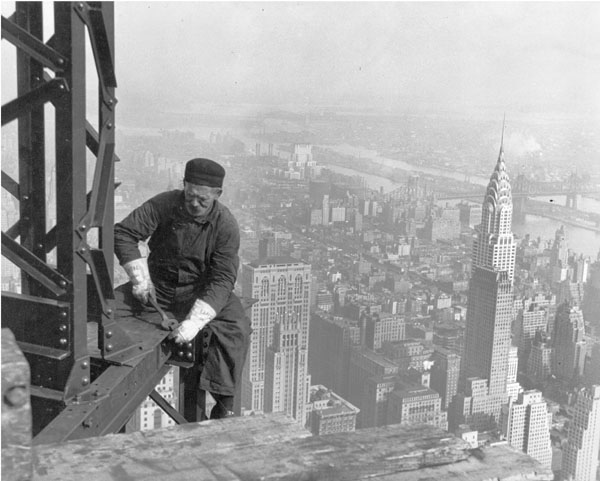

"Old-timer, keeping up with

the boys. Many structural workers are above middle-age.

– Empire State

[Building]"

Construction work on the

1250 foot high Empire State Building![]()

|

|

The basic philosophy of the "New Deal" As can be seen in the way Roosevelt attacked Hoover for his new government-spending programs – which is exactly what Roosevelt would come quickly to advocate early on in office – Roosevelt really did not have a specific set of plans in mind to deal with the Depression as he took office in early 1933. In his acceptance speech at the Democratic nominating convention in 1932 Roosevelt had talked about a "new deal" for the American people, though he had not given any details as to what that might specifically be all about. The idea "new deal" soon became the program "New Deal" (a term he chose which sounded quite similar to his uncle Theodore's "Square Deal") – and it meant whatever Roosevelt chose for it to mean as he struggled forward to put policies into play that might solve the problem of the Depression. Roosevelt's "Brain Trust"

Whatever it meant specifically, it meant generally that the national government was going to have to step into the realm of the economy and take the lead in getting things moving again. Roosevelt assembled an advisory council made up of a number of intellectuals (originally a small group of Columbia University professors, soon joined by a number of lawyers), that would come to be known as Roosevelt's "Brain Trust." These economic and legal experts would advise Roosevelt in ways to program the country out of the economic mess it found itself in. They would be the ones to put actual substance to Roosevelt's New Deal idealism. The "First 100 Days"

One of the early projects during the Roosevelt Administration's First-100-Days push was the National Recovery Administration (NRA) set up in 1933. It was a voluntary program that employers were supposed to engage in, promising that they would observe certain minimum pricing schedules for their products (to stop the competitive lowering of prices designed to drive the competition out of business) – and help their workers by offering at least minimum wages and maximum working hours. Those businesses which signed on with the program were permitted to display the Blue Eagle poster. But those that did not were often boycotted – and thus the voluntary nature of the program was compromised. There were complaints about this. Roosevelt also in those First 100 Days created the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) to provide three million jobs for young family men, building 800 national or state parks and planting three billion trees. He put some price-control policies in place (the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933) to help raise the incomes of the American farmer, essentially by taking land and thus crops out of production, thus raising the farmers' prices for their crops (but also making food more expensive for everyone else). Also in 1933 he set up the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to control the Tennessee River flowing through the heart of the American South, offering not only flood control but also electrical generation and transmission to the entire region, which previously had no electrical service. Supporting and regulating the banking and finance industry

In accordance with the Glass Steagall Act of 1933, Roosevelt set up the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as a guarantee to Americans that their bank accounts were protected by a Federal insurance guarantee against bank failure – thus putting confidence back into the American banking system (the FDIC is still in operation today). The Act also prevented commercial banks (which receive checking and savings deposits and extend loans to individual Americans) from involvement in the realm of investment banks (which buy and sell stocks, bonds and other securities). The next year, 1934, he set up the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to put the stock markets under federal regulation, to curb the excesses of speculation that appeared to have caused the problems in the first place – and to put confidence back into the American stock markets (the SEC is also still in operation today). He also in 1934 created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA also still in operation today) to insure home mortgages and thereby stabilize the mortgage market.2 The growth of government as industrialist

He also, through the Works Progress Administration or WPA of 1935, had the government move into the new realm of state-directed industry: the building of national highways, new libraries, government buildings, special camp and park facilities, even hydroelectric power generating dams. He hired artists to paint murals in public buildings and musicians and playwrights to compose new music and plays. His program even paid women to sew. Roosevelt also moved to strengthen labor's position in the bargaining with the owners of America's major businesses (The National Labor Relations Act or Wagner Act of 1935). This gave a tremendous boost to the American labor movement ... and made the labor unions very loyal to the Democratic Party after that. Social Security

And the New Deal set up a program of basic social security for the elderly in their years of retirement (the Social Security Act of 1935). The program also included unemployment insurance and welfare support for the poor and handicapped. 2Unfortunately,

much of the regulatory work of the SEC and FHA was most unwisely cut

back by the Bush, Jr. administration in the opening years of the 2000s

– presumably to help free up a slowing economy. Actually, what it did

was to help produce, through the so-called "shadow banking system," the

subprime mortgage crisis which started in early 2007 and reached the

level of a major financial meltdown in September of 2008.

|

One of his first promises fulfilled was the reversing of the 18th Amendment (Prohibition)

Hollywood celebrities toasting

the end of Prohibition – December 1933

Celebrating the end of Prohibition

A thirsty Clevelander takes

a deep gulp of beer with the end of Prohibition in 1933

The other promise was to

put America back to work again –

even if it took Government work to do

it

Harry L. Hopkins – Secretary

of Commerce, major architect of the New Deal ...

and close personal advisor

to Roosevelt

President Roosevelt confirming

Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor-

and the first woman to sit

on a presidential cabinet – 1933

Frances Perkins

National Archives

NA-208-PU-155Q-38

FDR at the site of the future

Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River, Washington State – 1934

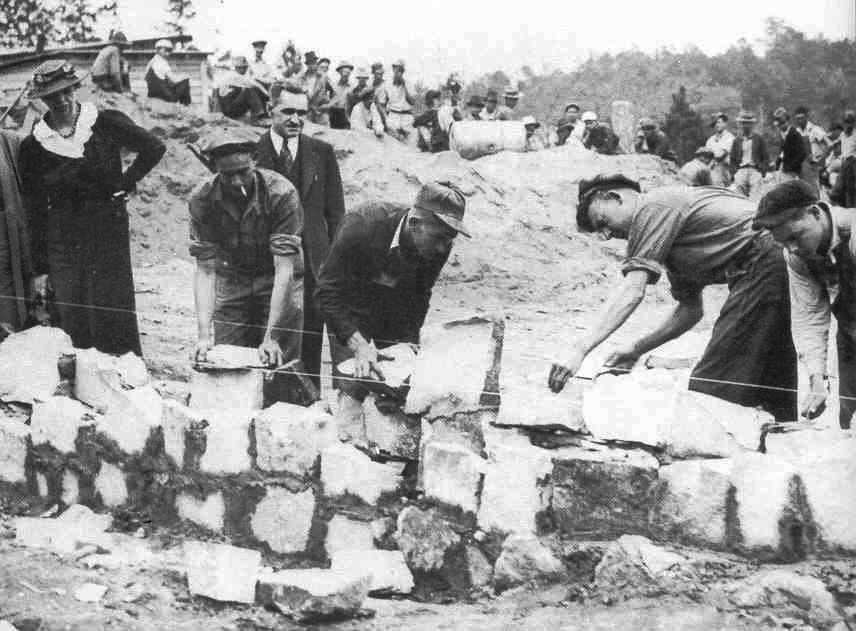

Civilian Conservation Corps

work site

A WPA highway construction

project

National Archives

A WPA project: New

York City ferry boat

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

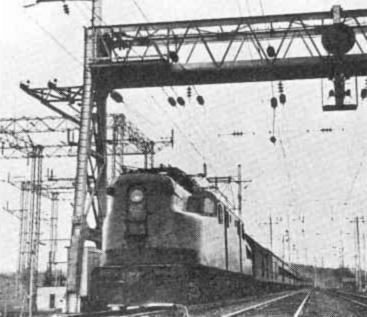

A WPA project:

Electrification

of the Pennsylvania Railroad

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Pavilion,

Huntington Beach, California

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

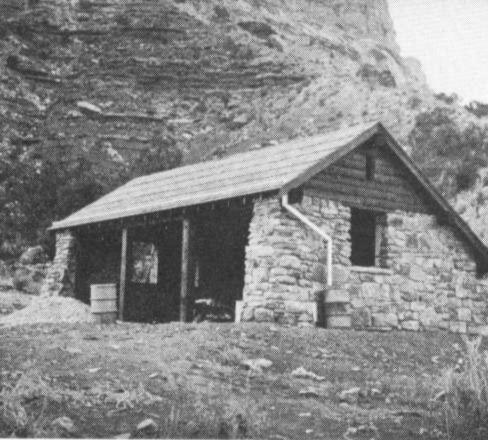

A WPA project: Work

Shed – Grand Canyon National Park

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

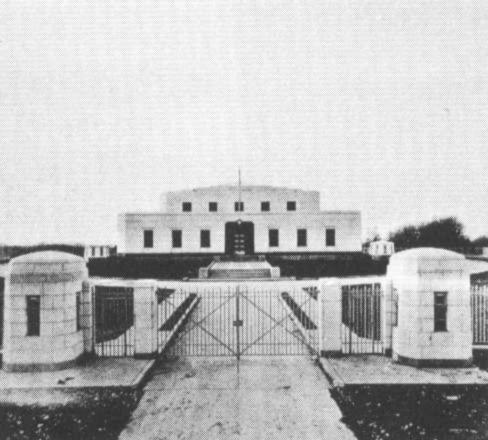

A WPA project: Mental

hospital, Camarillo, California

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

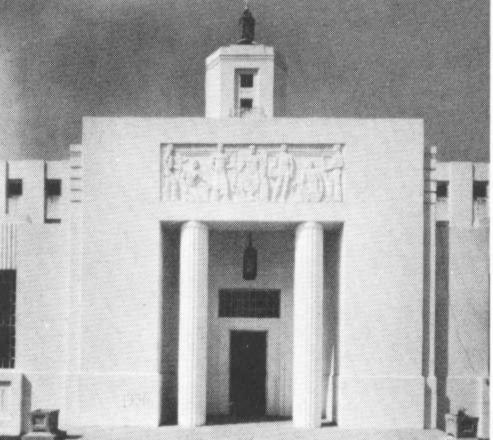

A WPA project: San

Francisco Fair

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Lincoln

Tunnel, New Jersey to New York City

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Gold

depository, Fort Knox,Kentucky

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Triborough

Bridge, New York City

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: The

Mall, Washington, D.C.

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Prison

Farm, Tattnall County, Georgia

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Boulder

Dam, Colorado River

By Ansel Adams,

Nevada

National Archives

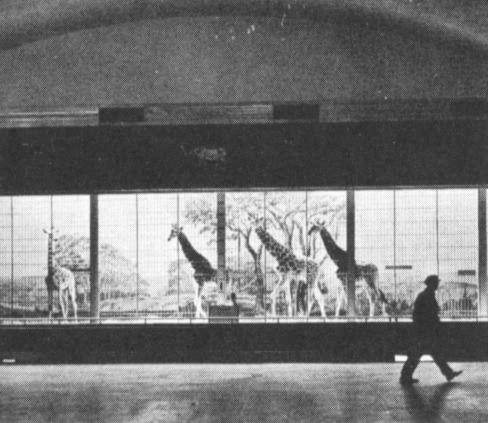

A WPA project: Zoo,

Washington, D.C.

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Swimming

Pool, Wheeling, West Virginia

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

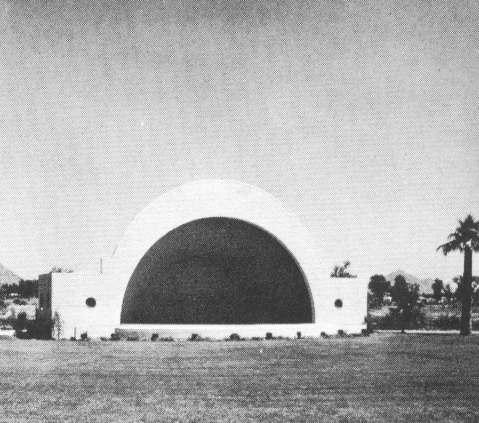

A WPA project: Band

shell, Phoenix, Arizona

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

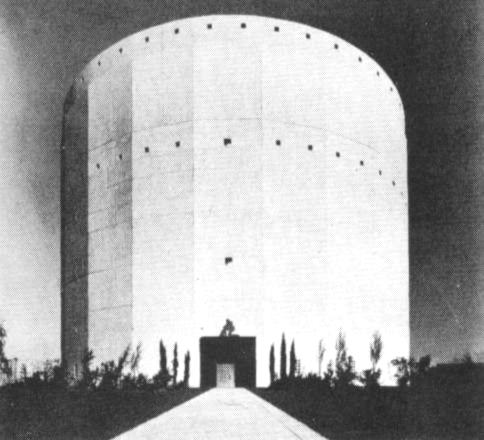

A WPA project: Water

tank, Sacramento, California

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: The

Jewel Box, Shaw's Garden, St. Louis

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

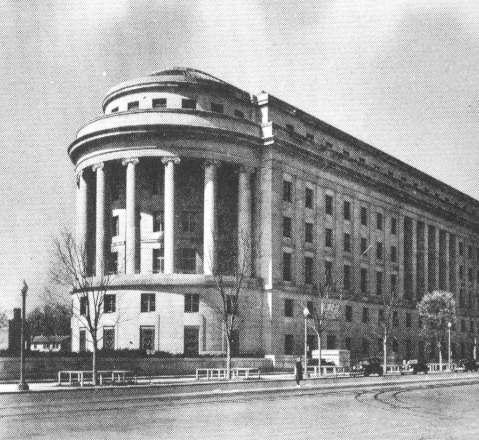

A WPA project: Federal

Trade Commission Building, Washington, D.C.

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

Increasingly, the nation looked to FDR to lead them through the troubled times

These families, about to lose their homes, appeal to President Roosevelt for aid

Part of his success in getting

the nation behind him was his way

of taking his case to the American people

over radio

FDR and his "fireside chat"

with the American people over the radio

Another part of his success was due to the warmth and energy of his wife, Eleanor

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt Foundation,

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Eleanor and

FDR

Eleanor Roosevelt visiting

a WPA work site in Covington, Georgia

Things seem definitely to

be improving – and the nation registers its approval

by re-electing Roosevelt

to office by a huge majority

The presidential election

of 1936

Department of the

Interior

|

|

The New Deal runs into serious problems

Roosevelt's first term in office, especially his First Hundred Days, saw the coming into existence of a massive number of government economic programs. Roosevelt seemed the master of the situation – and encountered relatively little opposition. But towards the end of his first term, and in the early part of his second term, Roosevelt found his programs coming under a lot of criticism – and even determined opposition. Criticism began to build about how his New Deal was becoming simply creeping Socialism. There was also mounting criticism about how many of these make-work programs were a waste of taxpayers' money. Jokes and sneers arose about all the standing around that seemed to accompany many of these work projects. Problems with the Supreme Court

The biggest problem however was the Supreme Court. By 1935 the Supreme Court was knocking down one program after another of Roosevelt's New Deal for being unconstitutional. According to the Supreme Court, there was no constitutional basis for the national government to be meddling in the affairs that were clearly reserved to the states as part of their jurisdiction. The worst blow came on Black Monday (May 27, 1935) when the Supreme Court pronounced unanimously on three cases – all of them going against Roosevelt's New Deal. The hardest of them for Roosevelt to swallow was the Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States case in which the Court declared that the NRA was unconstitutional. The NRA, in violation of the constitution's design of the separation of powers, had assigned legislative powers to the Presidency that belonged alone to Congress. But also Congress's use of the interstate commerce clause to justify the creation of the NRA program was clearly in excess of the powers allotted Congress by the Constitution. But more such anti-New-Deal decisions were to be handed down during the next year. The Court-packing scheme

Roosevelt was so upset by this personal rebuff by the Supreme Court that he decided to remake the ideological character of the Supreme Court. In early 1937 he announced that he would be introducing into Congress a new Judiciary Reorganization Bill, expanding the number of the Court's justices. The political intent was clear to all: he was looking to pack the Court, through the presidential power of appointment, with enough new justices to swing the Supreme Court rulings in his favor politically. The public reaction was negative, despite Roosevelt's many efforts during the spring of 1937 to enlist popular support for his idea. To the contrary. Opposition to the idea grew with the passage of time. Opposition in the House of Representatives was apparent from the outset, so Roosevelt introduced the bill into the Senate instead. But the Senate dragged on in debate. Eventually a split began to open up between the president and the senators of his own Democratic Party. Roosevelt was losing political ground fast. But in the meantime, a switch of votes in the Supreme Court had occurred, with one of the justices changing sides from anti to pro New Deal, and another justice retiring, thus giving Roosevelt the opportunity to make a new appointment. He now had a voting majority without having to pack the Court. Roosevelt backed down on his court-packing scheme. But he had lost a lot of political standing in the process. Many Americans felt that Roosevelt was taking notes from the highhanded ways of the European dictators, Stalin, Hitler and Mussolini. Roosevelt not only had gambled personally and lost in this contest, his attack on the Supreme Court also greatly weakened his ability to continue the political reforms he felt the country needed to undergo in order to get back to sound economic health. Bad economic news continues

This event was also timed with another slowdown in the American economy which hit in 1937, resulting in the growth again in the number of unemployed Americans. 1938 was not any better economically – and 1939 saw only a very slight economic recovery. There seemed to be little that Roosevelt could do to get the economy back on track again.

|

The U.S. Supreme Court -

1930

The U.S. Supreme Court in

session

|

|

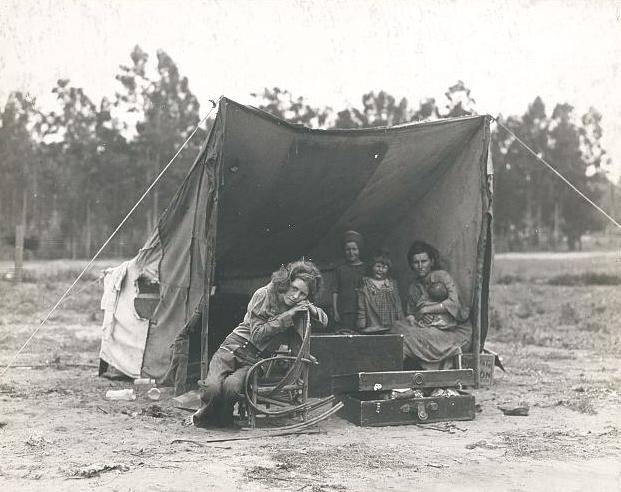

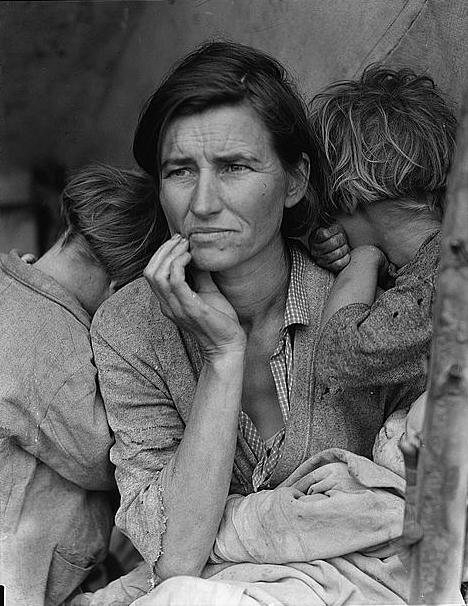

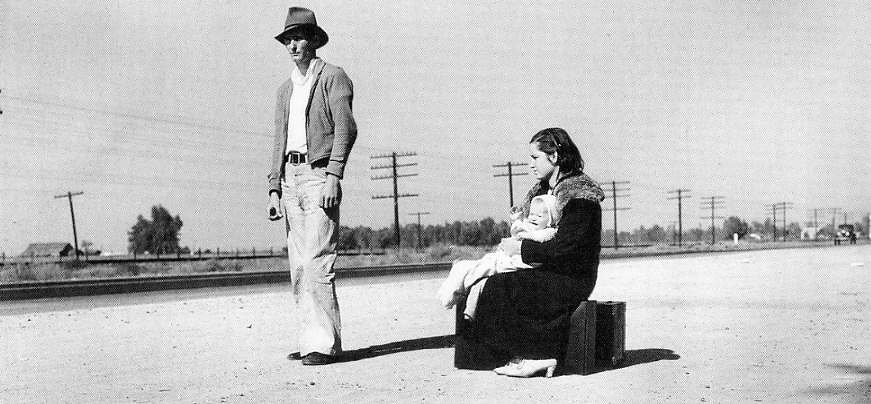

To make matters worse, during the entire 1930s,

but becoming incredibly intense in the mid-1930s, a deep and persistent

drought hit the Midwest states, worst in the Panhandle area of Texas

and Oklahoma, northwestern New Mexico, western Kansas, and eastern

Colorado – but extending all the way from central Texas in the south to

the Dakotas in the North. The topsoil was simply blown away by hot

winds which turned the air into black clouds of choking dust. Farms

were simply abandoned as destitute farmers headed west to California to

look for work – any work. Most of them ended up living in migrant

workers' camps under the worst conditions imaginable. People survived –

but only by toughening up tremendously. With all of this happening to America, Roosevelt found his popularity slipping during the latter part of the 1930s. He would not regain the popularity he had in the first of his terms in office until the entrance of America into World War Two in late 1941.

|

A dust storm in Texas -

1935

A dust storm about to envelope

Elkhart, Kansas – May 21, 1937

Prolonged drought throughout

the 1930s reduced the Kansas wheat fields to dust.

Library of Congress

LC-USZ62-35799E

One of the many dust storms

that hit the American Great Plains – 1932-1936

Library of

Congress

Two Colorado girls still

able to draw water from a well

amidst the storms raging

through the "Dust Bowl" – 1935

Dust Storm – by Arthur Rothstein

Library

of Congress

An abandoned farm in the

South Dakota Dust Bowl – May 1936

National Archives

NA-114-SD-5089

An abandoned farm in New

Mexico hit hard by the dust storms

|

"Dust Bowl" families heading

West

Library of

Congress

Oakie Family heading

West

(What's this? ... It looks like he just dropped his cell phone!!!)

Broken down on the road to

the West

Library of

Congress

A family living out of their

flatbed truck – California – February 1935

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

Migrant mother of Seven -

Nipomo, California – March 1936

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

Migrant mother of Seven -

Nipomo,

California – March 1936

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

A migrant worker's family

in Oklahoma – 1936

Library of

Congress

Heading west to California

in search of a better life

Library of

Congress

A young couple who had been

working the fields along Highway 99 in California's Imperial Valley.

Dorothea Lange, November

1936

Library of Congress LC-USF34-16102

A Texas family living in

a tent in Exeter, California – 1936

Library of Congress

LC-12466-F34-9841

A family fleeing the Southwest

Dust Bowl to California

A migrant worker

shaving

Library of

Congress

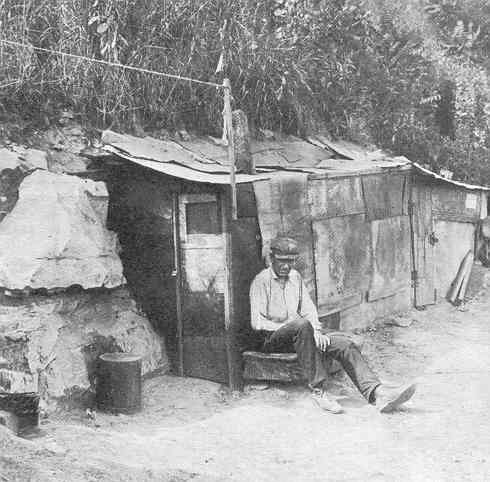

Migrant workers'

shack

Library of

Congress

Mother washing children's feet in a

sharecropper's shack in Missouri – May, 1938

Russell Lee

Library

of Congress

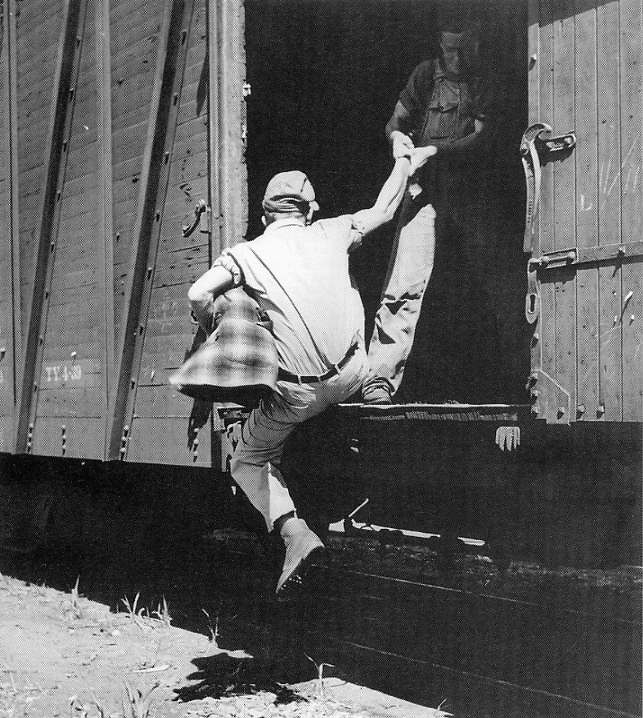

Family

who traveled by freight train – Washington, Yakima Valley – August 1939

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

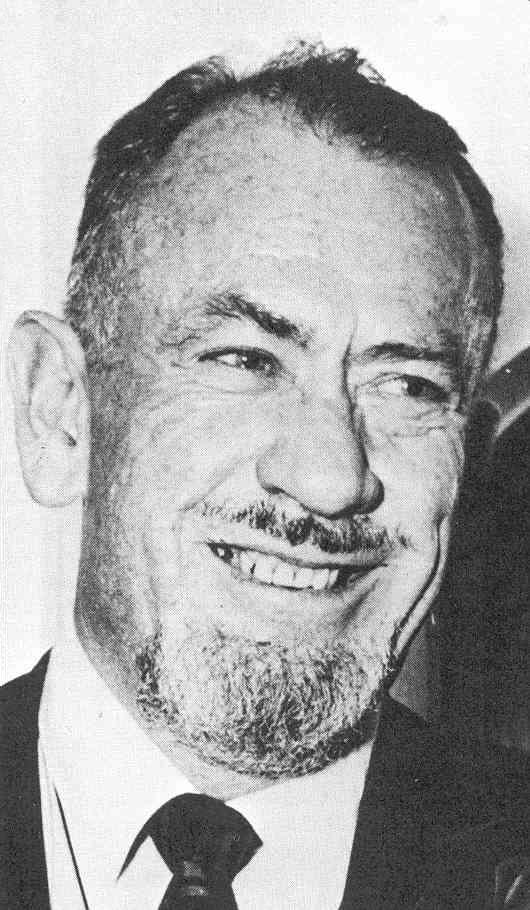

An individual who plumbed the depths of the American soul during this time was John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck

Tortilla Flat -

1935

Of Mice and Men -

1937

The Grapes of Wrath

- 1939

|

A Federal relief worker visiting

a Tennessee family in 1935

Daughters of a WPA worker

and a sick mother

Library of

Congress

"Cheap Auto Camp Housing

for Citrus Workers"

Dorothea Lange, Tulare

County, California, February 1940

Riding the rails – Bakersfield, California 1940

|

|

Actually, no! Not at all! It is common among

most Americans today to refer to how "Roosevelt's New Deal brought us

out of the Depression" when contemplating what to do in the face of a

new round of economic difficulties facing the nation. This popular myth

however is quite untrue. Certainly, the New Deal helped many idle

workers find work. It certainly built highways, dams, municipal

buildings, national parks, rural electrification, new rail services,

etc. Government projects were truly a blessing to many Americans

desperate to find work. But these projects did not solve the problem of

the Depression itself. The American Free Market or "consumer" economy

America has long been a grass-roots democracy not only in the area of government or politics, but also in the very nature of its economy. Unlike most societies of the world which throughout history have traditionally been driven by the economic wants or goals of the rich and powerful – emperors, kings, aristocrats and priests – the American economy has been built, since its origins in the early 1600s, on the interests of very ordinary people. There have been of course exceptions to this picture: the slave-holding South prior to 1865 and the Gilded Age of the late 1800s dominated by the captains of industry – or, as some would say, the industrial robber barons. But in general, the American economic system has been built on the labor, the product, and the economic desires of very ordinary citizens. The personal or private consumer is king

What determines what actually gets made

in America are the simple interests of the average American – known

simply as the American consumer. These interests of the American

consumer register themselves in what is termed the market place or free

market. The matter of what gets made, how much gets made, and what it

will cost, are all determined simply by how much interest the American

consumer has in a product when it goes to market. If it is a really hot

item, drawing strong consumer interest, it will enter the market place

quite pricey – and highly profitable to the producer. But other

producers with a typical American entrepreneurial spirit will want to

get into the act and also begin producing this highly profitable

product (or – under copyright laws – something somewhat like it) and

bring it to market – and themselves share in the blessings of high

profits. But this entrepreneurial urge will eventually be met with a

declining consumer interest – as most of the people who wanted these

hot items now are in possession of them (radios, cars, tractors,

washing machines, etc.). Unsold items will begin to pile up on the

market shelves. To move these items to sale, producers will attempt to

make these same products continue to be attractive – thus the American

advertising industry – but ultimately attractive through lower pricing.

Lower prices will help bring some additional consumers to the market –

but not at the rate that they were there when the item was hot. At this point the producer has to make some decisions. He can continue to make the product, though at a slower rate – which means he is going to have to cut back on production and let some workers go. He does not need their labor, and anyway, because his products are not selling well and profits are way down, he cannot afford to pay them. Or – he can switch to a new product, even a new line of products, simply to keep his business going. This means he has to be inventive, imaginative – and a natural risk taker. He needs to listen to the market, to the consumer, to sound the consumer out in terms of possible interest in new products. He can also go to advertising in an attempt to create consumer interest – by letting the consumer know in written or broadcast advertising, in words, song, or even drama, how wonderful life would be if the consumer only had his new product! But this is how the Free Market works. The consumer is king. It's all very democratic. There is no political authority dictating production or distribution or pricing according to official decrees. In fact, the American free market system has traditionally been highly suspicious of such governmental interventions into the economic system (commonly termed a "Command Economy") and tolerates only the slightest of such interventions under very special circumstances, and only for a limited time. For government intervention to go beyond that would be to undermine the whole idea of the Free Market system – and instead produce an economic system in which "enlightened" social authorities decide for the people themselves what they are going to get from the economy and how they are going to get it. This latter economic system is termed "Socialism" or "Communism" (although Fascism has many of the same characteristics.) Dealing with the business cycle

Of course, as with all social systems, this Free Market economic system is not without its problems. Market saturation such as described above, when most consumers have these products and therefore show a declining interest in them, is one of these problems. This is a big part of what was happening to the American economy at the end of the Roaring 20s. The market for consumer products stopped roaring. Because of this tendency of the market to heat up as new products are brought to market – and then cool down as the market becomes saturated – industrial production, and the economy in general, tends to move in cycles of growth, maturity and decline. Economists call this the business cycle. Economists have long attempted to find ways to smooth out the peaks and valleys of the business cycle, to make the economy steadier in its movement. But the very nature of the Free Market system itself seems to make it immune from such efforts. The famous English economist John Maynard Keynes put forth the idea in the 1930s that the business cycle could be modulated or smoothed by the government's interventions as the economy goes through the various phases of a business cycle. He advocated a governmental strategy of loosening money supply (creating more money for the market to work with) during the cooling phase of the business cycle and then tightening that money supply during period of a hot market. This Keynesian theory seemed to make a lot of sense to a lot of economists – and to a lot of government officials. In a sense Roosevelt's New Deal moved in accordance with this theory. But whether it actually contributed to – or simply slowed down – the recovery of the market economies in the 1930s remains even to this day a matter of great debate. What is not debatable is the fact that what a Free Market truly needs to keep going or get back going if it has slumped and fallen into idleness is new products. New products are what bring the consumer back to the marketplace to do business. In a sense the New Deal produced new products – but products desired not by the individual consumer, but collectively by the society, sometimes termed infrastructure items. These items are vital to the society as a whole … but beyond the scope of any individual or even group of individuals to produce or sell (or even finance). The New Deal produced highways, parks, public buildings, etc., social items certainly desired by the average American – but products that no one single consumer would have ever been able to buy. So in that sense the New Deal worked. Government-funded projects certainly met important infrastructure needs of American society. "Market saturation" for government products (roads, dams, parks, etc.) But even here part of the problem was that the New Deal suffered from its own version of market saturation. Under the New Deal a great number of national highways were built. But once built, Americans did not need new ones to replace them right away. Highway building slowed down. New dams were built at the most likely spots where energy could be cheaply generated. After that, dam building became much less cost effective. Dam building slowed to a halt. Parks were built – until the need for park building was greatly reduced. In short the government as producer was facing the same problem that the private producer had faced at the end of the 1920s: market saturation for government or social products. By the late 1930s, with the government forced to slow up in its building projects, unemployment began to rise again in America. Government intervention into the economy certainly had taken up some of the slack in an idle American economy during a good part of the 1930s. And it had brought good things to America. But it had not solved the basic problem of the Depression. The American economy simply seemed to have no urge to take off again on its own. That's because new personal consumer products were needed to bring the American consumer, the bedrock of the American economic system, back to market. But coming up with a new line of products to go to market with is not easy. It takes discovery, new technologies, changing circumstances – many things that are not automatically brought into being. And during the entire 1930s there really was no such development of new product lines by private industry. Some blame the New Deal itself for the failure of new products, new technologies, to develop during the 1930s. They claim that scarce investment funds were all used up by the government to push its own economic agendas. Financial capital that was needed to back up new inventions and new production was simply not available to the private entrepreneur because it was all flowing to the government. Perhaps this was true. But perhaps not. Clearly there was another factor involved that unquestionably shaped the way the private industrial system was to behave in the 1930s. Consumer confidence The New Deal put money in the pockets of the workers that built all these New Deal products. But what did the worker do with this money? In general, the worker put it away in a safe place. The old adage is that he put it under his mattress! Actually, he most likely put it in a savings bank. Thanks to Roosevelt's FDIC insurance of bank deposits, a savings bank was finally a safe place to put one's money. In any case he was not going to put it in the stock market any time soon. He was still too frightened about what might happen if he put his money there. So, workers' wages were of little help in producing a revival of the capital market which financed the business ventures of private manufacturers. The banks where he deposited his money were of no help to the capital market either. And it was not just because banks too had been scared away from involvement in that market. Actually because of the Glass Steagall Act of 1933 it was illegal for such commercial or depository banks to enter the capital market. Only banks licensed as investment banks were permitted to trade in the capital market. These were not the banks where the worker placed his savings. Investment banks were not permitted to do this simple kind of business. They were the banks you went to if you wanted to buy or sell (or borrow – though with new limits) corporate stocks, bonds or other kinds of corporate securities. Thus it was that workers' wages did not usually translate themselves into new inputs into the capital markets vital to the recovery of private industry. In short, the average American wage earner now suffered from the economic disease of lacking consumer confidence in the market place. He earned his money – and then put it away, where it would go unused in stimulating new market demands. And thus the market continued to sit quietly while little happened in the private economic sector. World War Two finally brought America out of the Depression

World War Two finally brought America out of the Depression. In the end what brought America out of the Depression was not the New Deal – but was World War Two, which the country embarked upon only at the very end of 1941. The war, and the war alone, proved to be the factor that would put America back to work. New products (uniforms, guns, fighter planes, bombers, tanks, trucks, cannons, battleships, carriers, submarines, etc.) would be needed in vast, virtually unlimited quantities. Every American that was not in uniform would be needed to support the war on the home front – in particular even young women working in the production and assembly plants where these products were manufactured. And there was no danger of market saturation – at least until the war was over. Such products were quickly destroyed in the action of war and thus immediately called forth replacement products. In the American economic system, the government did not make these products. Private industrial manufacturers did. Of course, the finished product did not need to go to market. The government was the market – under contract to buy the product as soon as it came off the assembly line. But as with the New Deal economy, the average American was the financial underwriter of the war economy. Part of this support was in the form of taxes paid to the government – which Americans were quick to offer because this was their war – not just their government's. But taxes were not sufficient to cover the huge government expenditures involved in this business of war. The government needed to go into deficit spending – borrowing money now with the promise to pay it back later, when the emergency of the war was over. And who was the lender to the government? The American people themselves. They lent to the government huge amounts of their personal industrial earnings (created by war production) – in the form of war bonds: contracts or certificates issued by the government which promised the American lenders that they would be repaid in the future, with nice interest earnings added. Purchasing war bonds turned the average American into a capital financier lending to the government. The possibility of guaranteed interest earnings was part of the motivation. Besides, what was a person to spend his or her money on anyway? Automobile manufacturers had turned to the business of making army trucks and tanks. No automobiles were manufactured during the war. Except for war goods there wasn't much of anything to spend your money on anyway. Everyone was under rationing so you couldn't even go on a food-spending splurge. So putting your money away in the form of war bonds made natural sense. Besides, it seemed to be one's patriotic duty. And that's how the American economy came

back to life. World War Two, not the New Deal, brought America finally

out of the Great Depression.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges