|

|

The growing Liberal-Conservative split

within

the church itself The growing Liberal-Conservative split

within

the church itselfThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 522-530. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

Bringing down the High Priests of Wall Street

With the failure of the former god Capitalism to make any kind of a comeback, a toughening American spirit turned itself into a vindictiveness against those responsible for the Depression. For instance, the elderly inventor and business tycoon Samuel Insull fled to France when the Stock Market collapsed, moved from country to country until he was arrested in 1934 by the Turkish government and sent back to America. Here he was sent to jail for a brief period. Actually, at his trial, the jury could not find him guilty of violating any particular law or laws, although he certainly was guilty of the moral sin of selling worthless stocks to people who trusted him because of his high position in Wall Street. Also the collapse of his holding company had wiped out the life savings of some 600,000 shareholders. Also, in 1938 a jury convicted and imprisoned Richard Whitney, former president of the New York Stock Exchange (1930-1935), after he pleaded guilty to two charges of grand larceny, having embezzled funds from the Stock Exchange Gratuity Fund (and elsewhere) to cover huge personal and corporate financial losses.

|

Some of this toughness translates

itself into a vindictiveness

against those "responsible" for the

Depression

Inventor and business

tycoon Samuel Insull heading to jail for a brief period – mostly as the

nation's

revenge on the mighty for their failure to sustain the Wall Street

dream. Actually the jury could

not find him guilty of violating any

particular law or laws.

National Archives

NA-306-NT-92795

Former president of the New

York Stock Exchange, Richard Whitney,

indicted after pleading

guilty to two charges of grand larceny.

|

|

Going after the mob

At the same time, Americans became much less tolerant of the colorful doings of America's urban bosses and the corruption and violence of the American mobsters. Hot on their trail was the Bureau of Prohibition agent, Eliot Ness – leader of the Untouchables, agents who would not accept bribes. And bringing many of them (at least the New York operations) to court was New York's Special Prosecutor, Thomas Dewey, who from 1935 to 1937 won seventy-two convictions in seventy-three of his cases (including Whitney's). So outraged by Dewey's relentlessness was New York mobster Dutch Schultz that he had scheduled a hit on Dewey in 1935 – but was himself gunned down by a rival gang in a Newark, New Jersey, restaurant just a few days before the scheduled event – which thus never took place! Dewey also ended the career of the New York mob fixer James J. Hines – a Tammany Hall ward heeler who had long protected the likes of Lucky Luciano, Dutch Schultz, Frank Costello and Joe Adonis by bribing police and judges – Dewey gaining a conviction and prison sentence for Hines in 1939.

|

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover

(center) and his inseparable friend Clyde Tolson (right)

National Archives

NA-65-H-301-8

Chicago mobster Al

Capone

Al Capone leaving the federal

court in October 1931, convicted of tax evasion

John Dillinger hiding out

at his dad's house

Eliot Ness – leader of the

"Untouchables" – Prohibition agents who would not accept bribes

While the authorities began

to chase down urban crime,

desperation in the countryside

sparked a new wave of crime there

Bonnie Parker (23) and Clyde

Barrow (25) – 1934

Bonnie Parker – gun-Moll

Their reign of violence (12 murders and countless bank robberies across Texas, Oklahoma,

Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Louisiana, Illinois, Ohio, New Mexico and Indiana held to their account!)

ended with their own deaths at the hands of six officers in Bienville Parish, Louisiana – May 23, 1934

The bullet-ridden car that

Bonnie and Clyde were driving when they were gunned down by law

officers

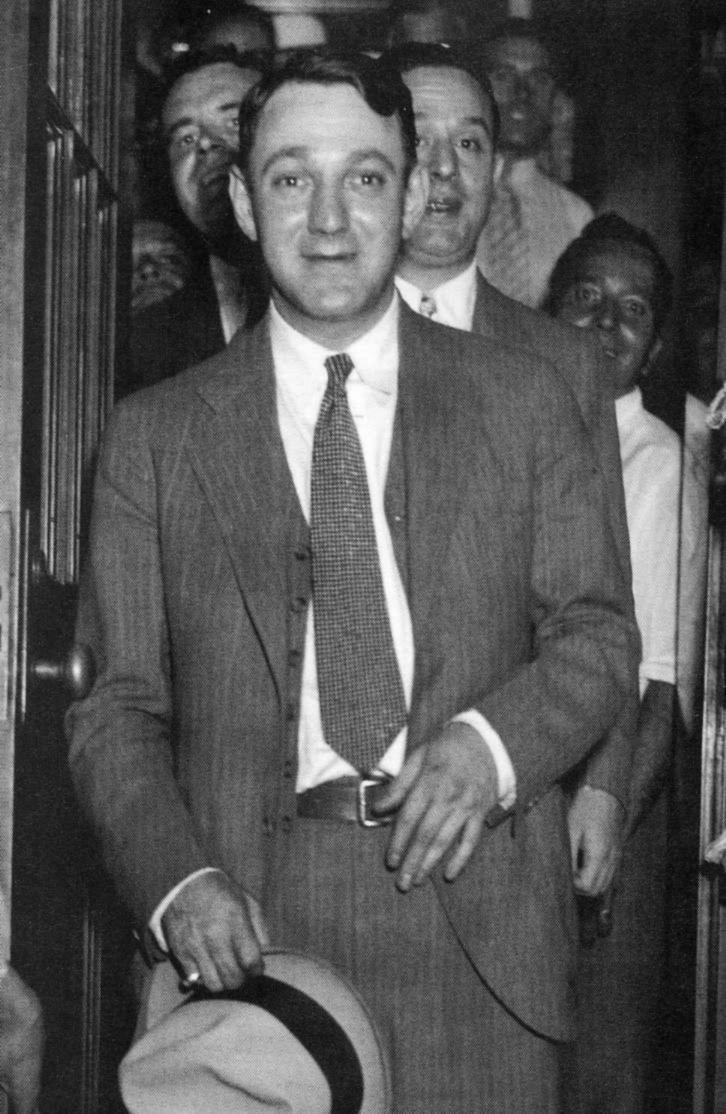

An "innocent" New York mob

leader Dutch Schultz

leaving a tax-trial in Malone,

New York – August 2, 1935

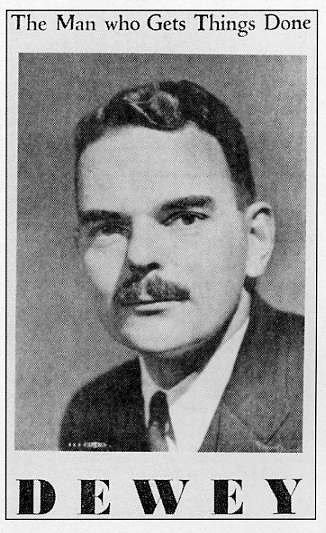

Campaign poster for Thomas

Dewey – running for NY Governor – who was at that time

New York's Special Prosecutor – who from 1935-1937 won 72 convictions in 73 of his cases

(An outraged Dutch Schultz

had scheduled a hit on Dewey in 1935 –

but was himself killed just

a few days before the scheduled event – which thus never took

place)

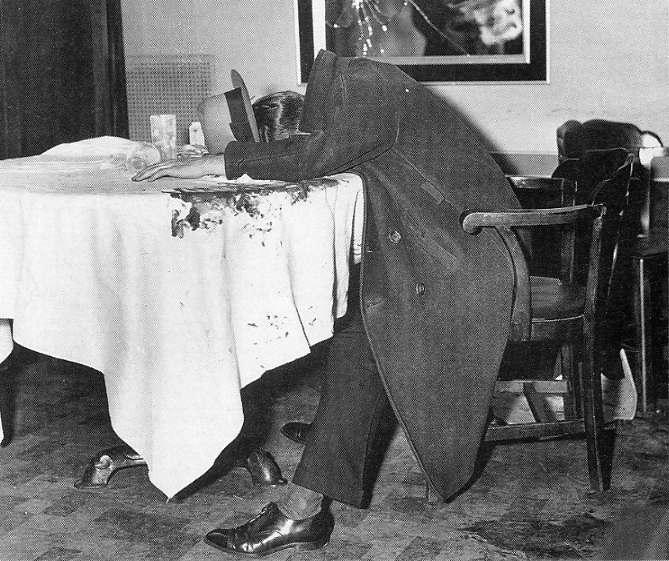

Dutch Schultz – gunned down

by a rival gang in a Newark, NJ restaurant – October 23, 1935

The New York Mob's fixer

James J. Hines

A Tammany Hall ward heeler

who protected the likes of Lucky Luciano, Dutch Schultz,

Frank Costello and Joe Adonis

by bribing police and judges. Thomas Dewey finally

succeeded in putting his

career

to an end with a conviction and prison sentence in 1939.

New York Mayor Fiorella La

Guardia –

surprisingly, reputed to be of excellent moral character ...

and recognized as one of America's outstanding mayors

|

|

The failure of the high priests of capitalism was also met with the rise in labor militancy, demanding better wages and working conditions – and displaying a readiness to shut down American businesses that did not meet these demands. Labor unions were not waiting around to see what economic wonders might come their way. They were quick to move to safeguard and extend their economic position wherever they could. And of course there was a degree, at times quite high, of ideology involved in this dynamic, inspired in part by the American Communist Party, in part simply by the ambitions of labor leaders themselves, and by the continuing infusion in the ranks of American labor by immigrants with European political attitudes – at least Socialist if not even Communist. Likewise on the business side of the conflict there was an equal ideological-philosophical concern. Capitalists had not only lost their former place of glory, they had become the object of wrath, for having "caused" the Depression. But they themselves had lost whole fortunes, were struggling to keep business operations going, and were confused and angry – hungry for some kind of idea or philosophy that could restore for them a sense of social pride rather than scorn. Tensions even beyond FDR’s New Deal operating out of Washington were running hot in the rest of the nation. In May of 1934 a massive general strike called by the dockworkers of the entire West Coast (joined by merchant sailors) succeeded in shutting down the ports that fed the West Coast. Working conditions at the docks were tough (as they were also in the mines and factories of America), and the striking workers were demanding $1 an hour wages – and no more than six hours of work per day or 120 hours per month. And in shutting down the ports, they had a strangle-hold on the cities lining the coast, most violently San Francisco and Seattle where the strike dragged on and in early July turned violent. Roosevelt tried arbitration, but the strikers were not interested in any compromise. Police and then troops were brought in and two workers were killed. At the same time, sailors refused to dock their ships to unload their cargoes, and truckers refused to pick up and ship inland goods that had been unloaded – in sympathy with the striking workers. But eventually no one was gaining much in all this. Finally in October a compromise was reached in which the workers made almost the $1 per hour wage, the promise of safer working conditions, and shorter working hours. Leading the way through all this was the very charismatic labor union leader John L. Lewis – not only willing to take on big-business (actually not so big at this point) but also the Republican Party, which traditionally had stood so strongly in support of American capitalism. A favorite target of Lewis was Kansas governor Alf Landon, running as the Republican presidential candidate in the 1936 elections, whom Lewis accused of being a mere puppet of the steel industry. There were, of course, still many unemployed men out there eager to find jobs. And when union members went on shutdown strikes against their employers their employers were more than happy to offer the positions of the absentee workers to newcomers – or "scabs," as striking workers called them. The hatred of the two groups, strikers and scabs, became very violent, as for instance during the 1937 Republic Steel strike in Cleveland, in which a battle between the two groups (and police) resulted in eighteen deaths.

|

American Labor is no longer intimidated by the failed gods of capitalism

Union leader John L. Lewis.

Labor leader John L. Lewis

denouncing Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon

as being merely a puppet

of the steel industry

San Francisco butchers parading on Labor Day

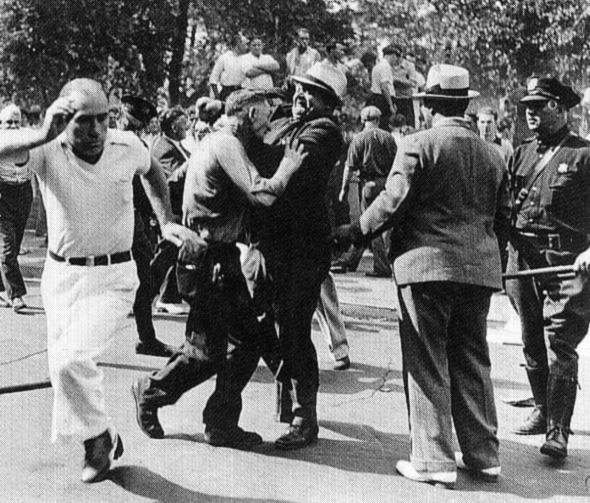

Cleveland cop trying to break

up an effort by strikers to overturn a foreman's car

"Sit down" strike of United

Auto Workers at the General Motors Plant in Flint, Michigan in 1937

GM workers in a sit-down

strike to protect their right to unionize workers – 1937

Wives supporting striking

husbands at the Chevy Plant in Flint, Michigan – 1937

GM workers celebrating their

victory in getting the United Auto Workers

union recognized by

management

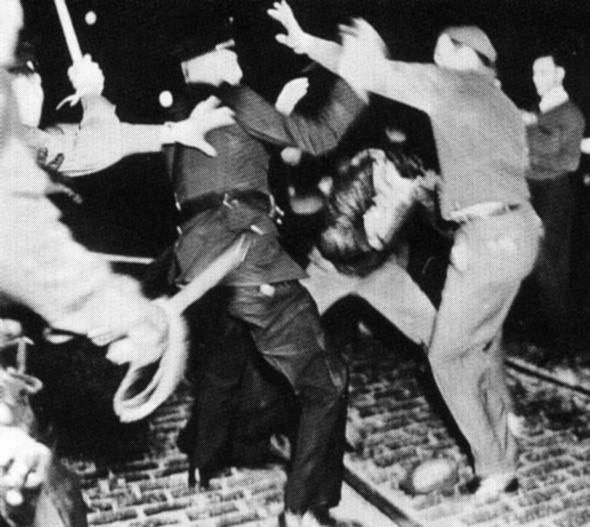

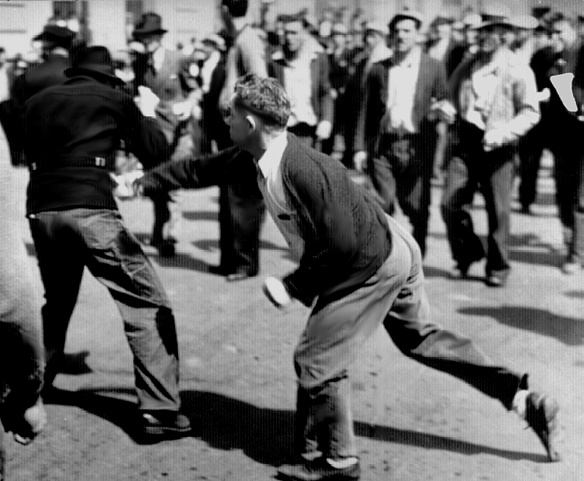

A bloody battle between strikers

and "scabs"

(those hired by the company to take over the jobs of the striking

workers)

in the May 1937 strike at Republic Steel in Cleveland (eighteen workers lost their

lives)

A display of muscle between

strikers and police also brings tragedy at a picnic of workers and family

at Republic Steel in Chicago – also in late May 1937

The 1937 Memorial Day Massacre

by police at the Republic Steel plant in Chicago

264 Chicago police attacking

a Memorial Day picnic of approximately 1000 unarmed strikers and

family

members at the Republic Steel plant. 10 were shot dead,

another 30 were

wounded, and nearly the same number suffered serious head

injuries from police beatings.

Police attacking strikers at the Republic Steel plant in South Chicago

Ford Motor Company toughs

hired by Harry Bennett of Ford's "Service Department"

approach union leaders Robert

Kanter, Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen,

who are passing out union

pamphlets at the River Rouge plant – May 1937

The toughs set to work on

Frankensteen

Reuther and Frankensteen

after the beating

(they were also thrown down

a flight of 39 steps after the beating)

Striking Pennsylvania steel

workers attacking the Rev. H.L. Queen

who was a management

spokesman

Police breaking up a strike

of Ohio rubber workers in Ohio

Police breaking up a strike

of machinists in New Jersey

Chrysler strikers warning scabs to stay away

San Francisco longshoremen attacking scabs along the waterfront – 1938

Fiorello La Guardia discussing

the WPA strike with reporters in Washington – 1939

|

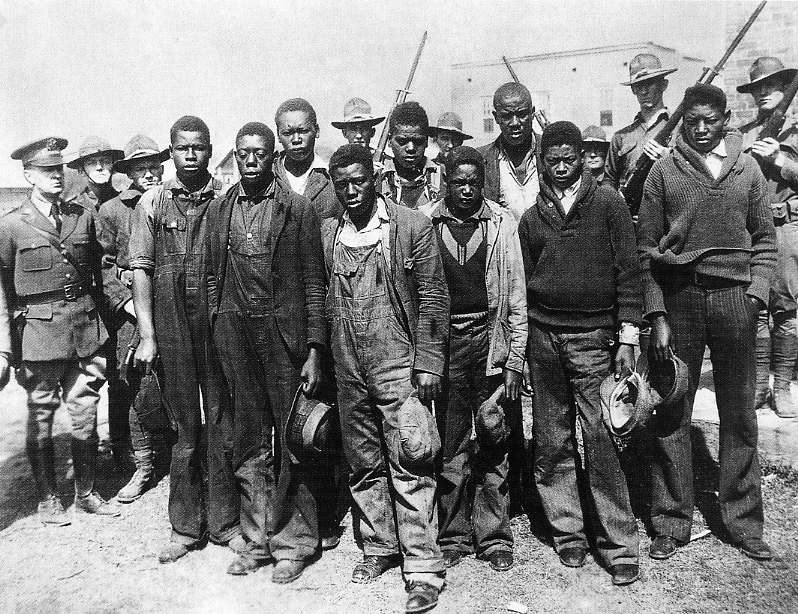

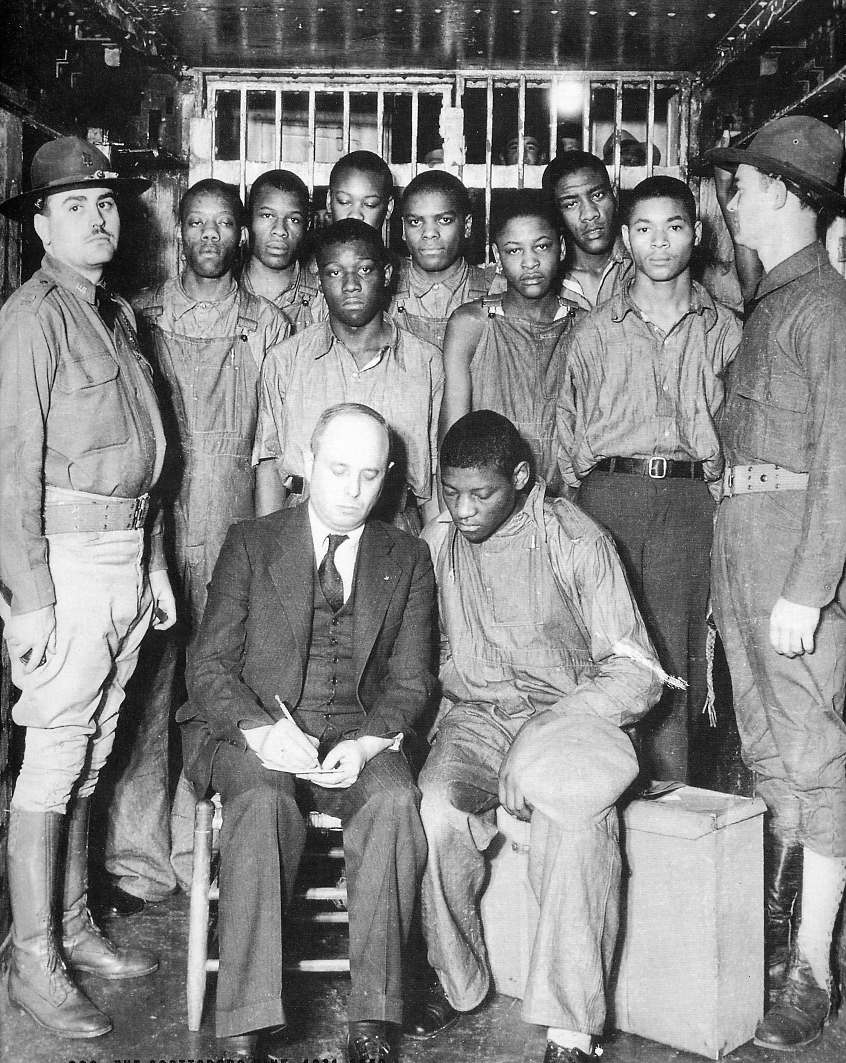

The "Scottsboro boys"

Corbis / Bettmann -

UPI

|

When in 1931 Alabama police discovered 11 itinerants on a freight train, the two women among them claimed that the others – Black youth – had raped them. Doctors found no evidence to corroborate the womens' stories. Yet 8 of them were found guilty and sentenced to die. The Supreme Court threw out the Alabama case twice before Alabama finally backed down. Even then, Clarence Norris (second from left) remained in prison until 1946. |

The Scottsboro Nine -

1931

A Plea For Clemency In the

Scottsboro Negro Case, by Matthew Woll – 1933

Saint Louis children and

their parents behind a police line

during their protest against

transfer to a school open to black children, March 1933

Library of

Congress

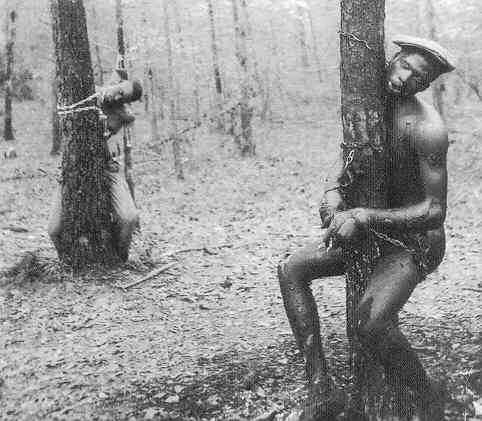

Two Blacks lynched for an

alleged murder in Winona, Mississippi – April 1937

|

|

America's home-grown variety of Fascism

While the country seemed to be falling apart in a desperate scramble of Americans simply to find work, feed a family and stay alive, Germany clearly had its act together. The contrast between the precise order of Germany and the listless wandering of America was quite upsetting to many Americans. Indeed, it even seemed in America to be a very bad time for democracy – and for its cousin, free market economics or capitalism. State-managed (even dictated) life seemed to work better in providing the people a much better life than a free market capitalist economic system and a democratic government representing directly the clear voice and will of the people themselves. Strong leaders (such as the German Führer, Hitler; the Italian Duce, Mussolini; the Soviet First Secretary, Stalin; etc.) seemed to know better what would work best for the people than the people themselves. Political elitism seemed to be the better way to embrace the future. Indeed, America (as also other countries such as Great Britain and France and Spain) seemed to be producing their own varieties of Fascist or Communist or Populist leaders. The times seemed to demand bold leadership. And there were a number of American candidates willing to put themselves forward as just the answer to the nation's problems. Father Charles E. Coughlin

Through his radio reach to forty-five million regular listeners, this powerful Catholic priest put forth stinging social commentary on the times. He could be really biting in his attack on the flaws of the country. Eventually he moved more and more to the ultra-Conservative Right, becoming increasingly anti-Semitic and anti-New-Deal – even pro-Fascist with respect to events in Europe. The "Kingfish" Louisiana Governor Huey Long

Quite a different style was forthcoming from this ambitious Southern Populist, who talked about taking the money from the rich and giving it to the poor so that there could be a chicken in every American pot. Statistically that made no sense, because confiscating the wealth of the rich would have made little financial difference to the millions of poor Americans. But the rhetoric sold well – until an irate medical doctor shot and killed this little Führer wannabe. "Roosevelt actually saved capitalism."

A thesis argued back and forth is the idea that Roosevelt's New Deal actually saved capitalism. There is no way actually to prove or disprove what exactly it was that were Roosevelt's true thoughts and actual intentions concerning capitalism. He certainly picked up much of the language of the radical Left in attacking capitalism as an insensitive, deficient economic philosophy, although it has been argued that he did so only to steal the thunder of a small but growing American Communist Party, the American Labor Party, and the Farmer-Labor Party, rising political movements which advocated all-out Socialism as the policy that America must turn to in order to save itself. Roosevelt purposely opened the ranks of his New Deal organization to rising leaders within those Leftist movements, to undercut the possibility of them becoming third-party movements which would steal millions of votes from the Democratic Party, thus preventing these parties from inadvertently (as third-party movements always do) advancing the Congressional position of the Republican Party opposition. Certainly, given the rising anger of impoverished Americans – on the farms and in the industrial cities – Roosevelt helped head off the political urge of millions of Americans (perhaps as much as a quarter of the citizens) to want to push America toward the National Socialism (Italian Fascism or German Nazism) on the one hand or the Workers' Socialism (Russian Communism) on the other that seemed to be working so well in Europe. But exactly how Roosevelt’s politics saved capitalism is not quite clear, because throughout the rest of the 1930s – until World War Two when American capitalists were called on to rebuild a huge wartime economy – capitalism itself remained the bad boy in popular thinking.

|

Radio personality Catholic Father Coughlin takes on Fascist tendencies

Father Charles E. Coughlin, 1891-1979

| Through his radio reach to

45 million regular listeners, he put forth social commentary on the times. Eventually he moved more

and more to the ultra-conservative right, becoming increasingly

anti-Semitic and

anti-New Deal – even pro-Fascist with respect

to events Europe. |

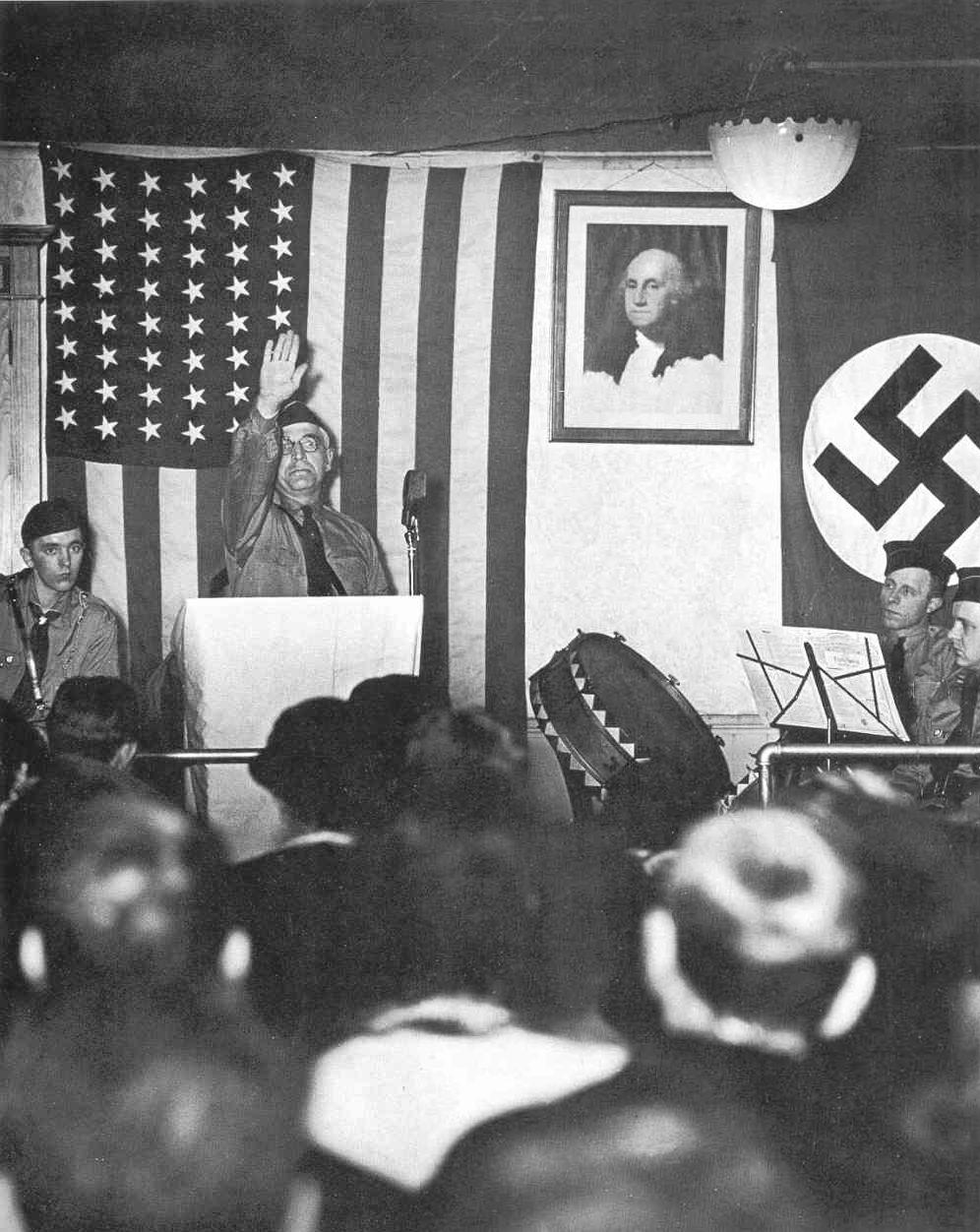

Some Americans even openly espoused Nazi sentiments – as loyal Americans, of course

German-Americans at a 1938 meeting in New Jersey of the Deutsche Bund

And then was the strange

and highly flamboyant populist figure the "Kingfish"

Governor Huey Long

of Louisiana

Louisiana Governor Huey

Long

Demagogic Louisiana Governor

Huey Long and supporters

Huey Long – the "Kingfish"

of Louisiana

National Archives -

NA-306-NT-315J

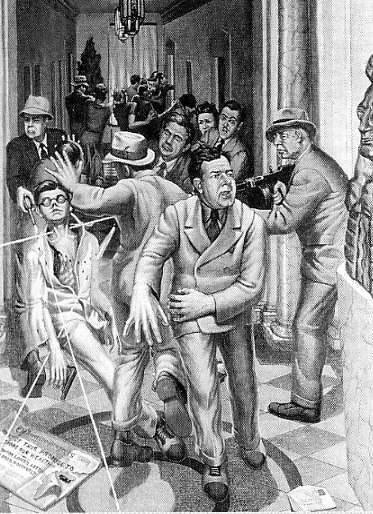

Huey Long shot down by Dr.

Carl Weiss – September 8, 1935

as Long was leaving the

Louisiana State Capitol building

From The Shooting of Huey

Long, 1939, by John MCCrady

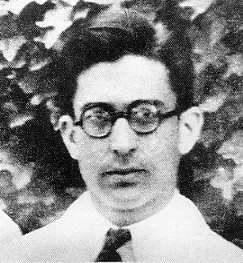

Dr. Carl Weiss – who shot

Huey Long to avenge Long's gerrymandering

of his father-in-law out

of a judgeship

|

Roosevelt attempts to keep up a positive view on things

FDR – exudes the spirit of

"happy days are here again" – 1939

Will Rogers – "Aw, shucks" showman

Will Rogers – America's favorite

comedian (but died in a plane crash in 1935)

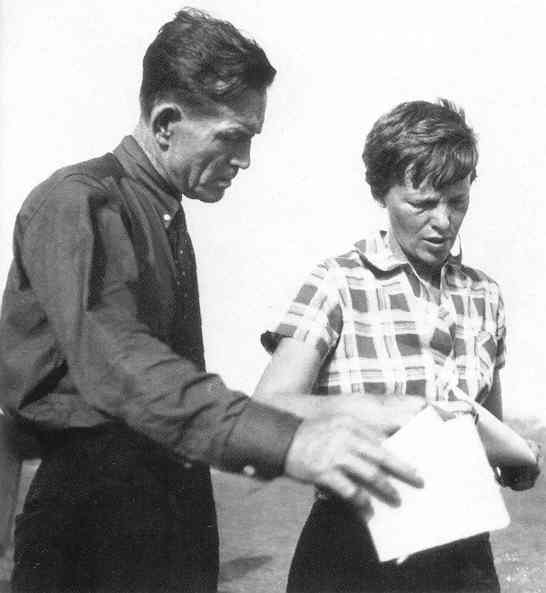

Amelia Earhart

(1897-1937)

The first woman to fly from

Hawaii to California;

but she went down in the

Pacific in 1937 attempting to circumnavigate the globe

Amelia Earhart and her navigator

Fred Noonan plan their round-the-world flight -

but disappear in July of

1937 out of New Guinea

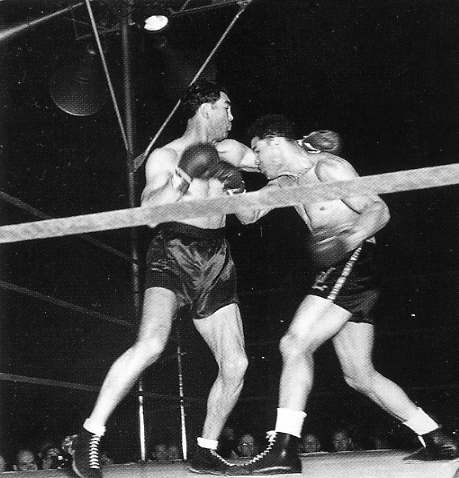

Heavyweight boxing champion

Joe Lewis and his manager, John Roxborough

Joe Lewis at a much publicized

rematch with German champion Max Schmeling – 1938

(Lewis dropped Schmeling

two minutes into the first round)

|

Radio provided its own home-spun heroes

Fibber McGee and

Molly

George Burns and Gracie

Allen

Ozzie and Harriet

Nelson

Amos and Andy (Freeman Gosden

and Charles Correll)

Charlie McCarthy (the puppet!),

Edgar Bergen and W.C. Fields

Hollywood glamor queen Jean

Harlow – 1911-1937

And there was the fashionable. wealthy upper class of the "cafe society" to keep everyone distracted

Doing the "Lambeth Walk" – an import from England in 1938

Debutante Brenda Frazier

leading the Grand March at the Velvet Ball

Socialite Alfred B. Vanderbilt

dancing with film star Joan Crawford

at the 1937 Screen Actors

Guild Ball in Los Angeles

Things were not always so

glamorous with the Cafe Society

English KIng Edward VIII

who abdicated his throne

in order to marry divorcee

Wallis Simpson – 1936

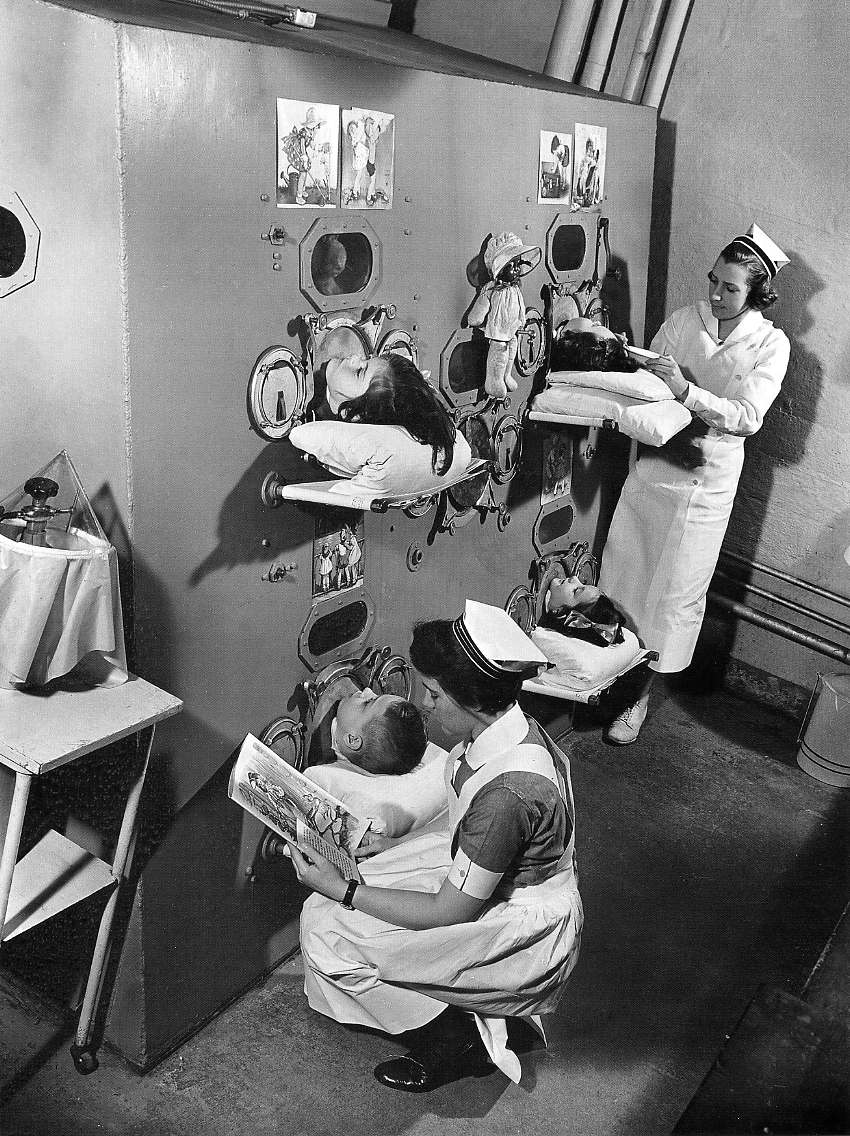

The iron lung helping young

polio victims breathe – Cambridge, Mass

|

The Wizard of

Oz

The Civil War epic movie

(220 minutes in length) Gone with the Wind

Orson Welles and the War of the Worlds hoax – October 1938

|

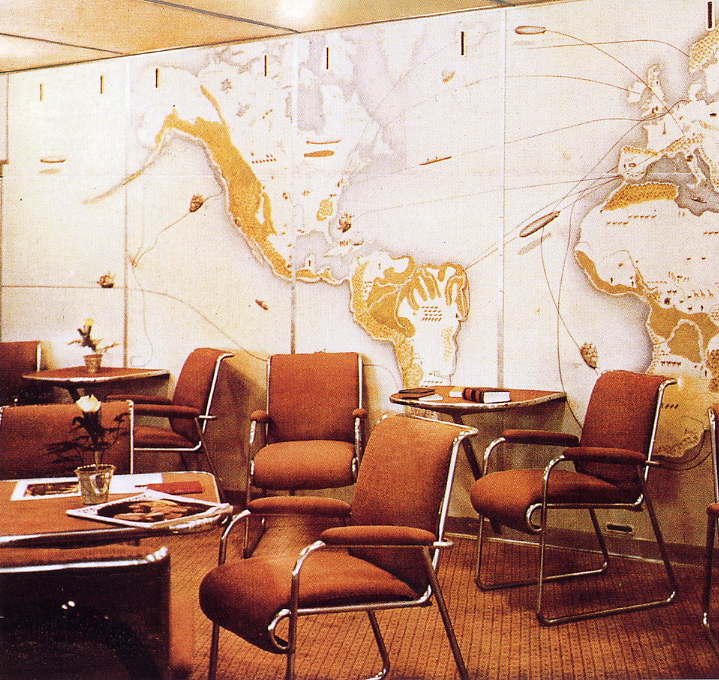

The lounge of the

Hindenburg

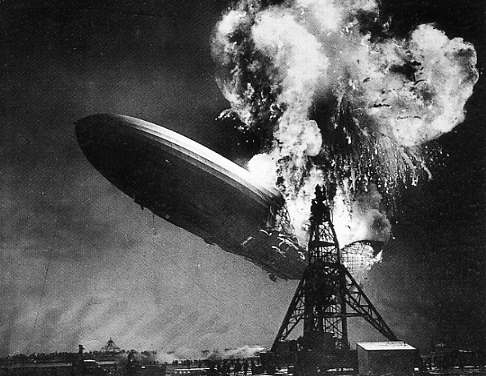

The Hindenburg burning at

its moorings at Lakehurst, NJ in 1937

(it was only 76 feet shorter than

the Titanic; 61 of the 97 aboard survived)

|

|

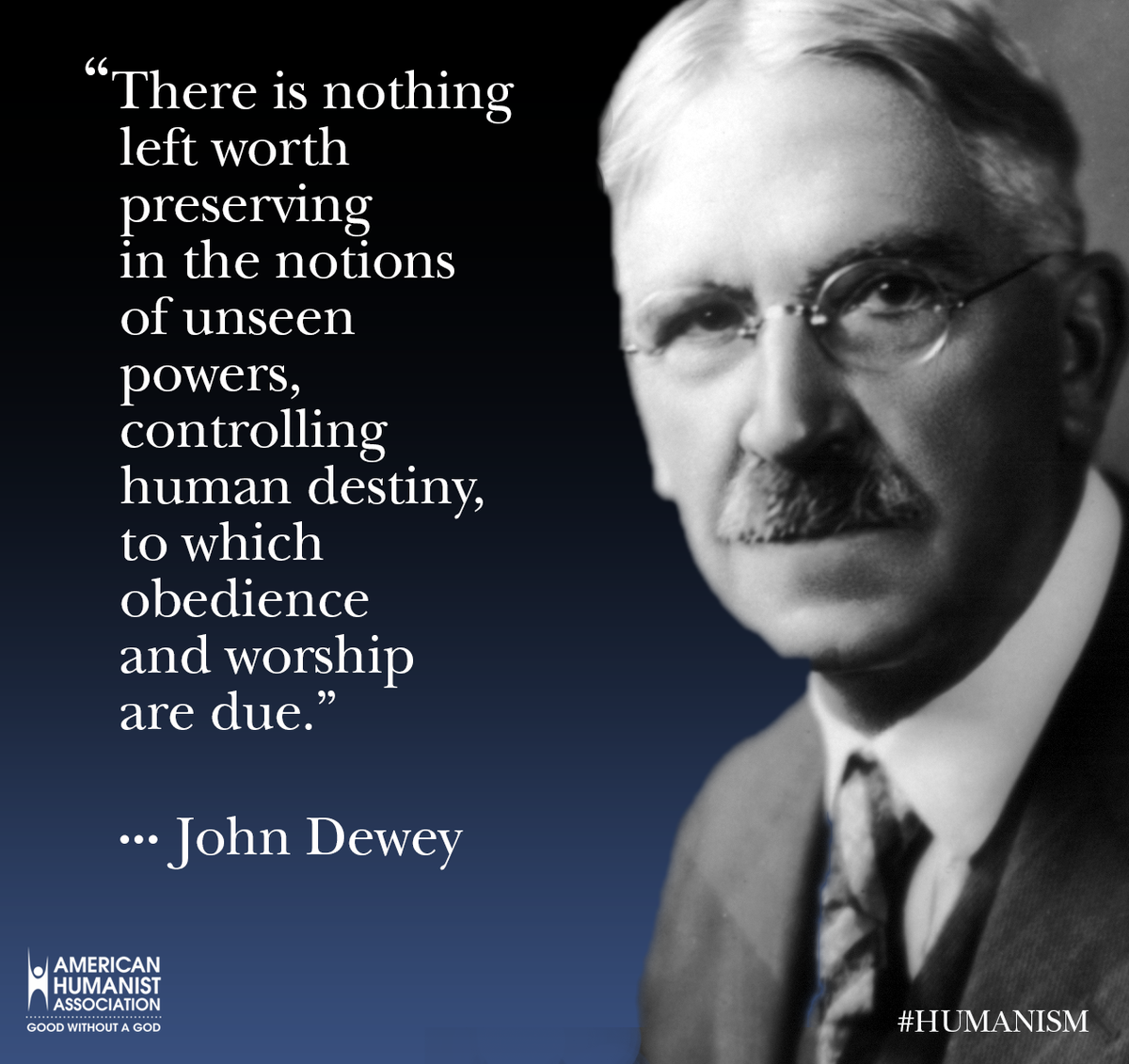

Liberal Humanism vs. Traditional Christianity

Meanwhile, all this economic stress was also shaking the very spiritual foundations of the country. What had happened to America? It seemed almost as if America’s God had failed the country. In fact, who exactly was at fault? And what exactly at this point could be done to get the country up and moving again? The very popular early 20th century American philosopher John Dewey, who more than anyone else shaped modern American Liberal views on education and social reform, was a self-avowed Humanist who believed completely in the power of human logic and in man’s basic goodness. There was no place in his worldview for God – though he did not attack the idea directly. He simply moved on past the idea of God to build his ideas of secular Liberal reform entirely around the notion of man’s instinctive logic and good intentions. In this he was very typical of a growing segment of intellectual America. To Dewey's way of thinking, Christianity needed to be pushed out of its central position as the foundational worldview of Western society and culture in order that the way could be made for the birth of a new religion, a secular religion originally identified as Humanism (referred to more often today as Secular Humanism, or just simply Secularism). The 1933 Humanist Manifesto calls for a new religion

In 1933, thirty-four individuals well-placed in the world of academics, the publishing industry, and Unitarian ministry, published a Humanist Manifesto – calling for a new religion and an accompanying social order focusing on the powers of man. Among those signers was, unsurprisingly, John Dewey. The goal of the Humanist Manifesto was to take up the responsibility of restoring a bright light of human optimism in the midst of a very gloomy Great Depression America. The Manifesto declared that the time had passed for "mere revision of traditional attitudes." It was time to come to terms with "new conditions created by a vastly increased knowledge and experience." Thus: . . . any

religion that can hope to be a synthesizing and dynamic force for

today must be shaped for

the needs of this age. To establish such a The Manifesto's fifteen affirmations made clear the specifics of this necessary new religion ("Religious Humanism"). Its beliefs were: no creation but simply self-existent creation; man as an evolved natural creature; truth only through scientific study; the end to theistic (God based) religion; social concern and service to replace the self-serving profit motive of capitalism; the need to embrace life rather than flee from it (seeing traditional religion, as the famous psychiatrist Freud claimed it to be, as escapist in nature). Of particular interest are several of the Manifesto’s affirmations. In the Ninth Affirmation it claims that humanists will replace "old attitudes involved in worship and prayer" with "a heightened sense of personal life" and "a cooperative effort to promote social well-being." In the Tenth Affirmation the Humanists proclaim that in their Humanism "there will be no uniquely religious emotions and attitudes of the kind hitherto associated with belief in the supernatural." In the Eleventh Affirmation they claim that in approaching life’s crises, employing "reasonable and manly attitudes" – acquired through education (their version of education, of course) – that their Religious Humanism "will take the path of social and mental hygiene and discourage sentimental and unreal hopes and wishful thinking." In the Thirteenth Affirmation, they make it very clear that the intent of Religious Humanism is to remake the religious life of the nation around their modern religious ideals and to see that particular traditional church practices and activities "be reconstituted as rapidly as experience allows, in order to function effectively in the modern world." It is very important to note that the Humanists of the 1930s were well aware that in their fervor for Humanism they were pushing for the establishment of a new religion in America. They intended at that time to do so simply by appealing to the common sense of a greatly distressed American people (thanks to the Depression) to see that the old days were gone. It was time to go modern. But things did not ultimately go that way. World War Two came, the Depression consequently disappeared, America came out of that war victorious and ever stronger in its Christian faith. This was not the way the Humanists wanted to see things go and did not give up their battle. But instead of appealing to the American people, they eventually went to the federal courts, complaining that Christianity’s central place in American culture was in violation of the Constitution’s "separation of church and state" – their own (and Jefferson’s) interpretation of the words of the First Amendment.1 And therefore something "not religious" – like supposedly their "secular" Humanism – should properly be the only foundational cultural principle supported and defended by the federal courts. In this quest, the Humanists got the Supreme Court finally to bow to the Humanist viewpoint in the 1971 case of Lemon v. Kurtzman. In that case the idea that secular Humanism was itself a fundamental worldview or religion was not mentioned (of course not). The embarrassing 1933 Humanist Manifesto (which would have made a complete lie of the Humanists' position in the case) was conveniently overlooked. And the Humanists were quick in 1973 to come out with Humanist Manifesto II, which drops the affirmation that what the Humanists are doing is pure religion, and instead recasts Humanism as simply "scientific Truth." But all religions are about what a community sees as fundamental Truth, the kind of Truth that everything else about their society’s norms and laws flow from faithfully. But anyway, there it is, the 1933 Humanist Manifesto, admitting that it is seeking avidly to bring America to a new religion. 1"Congress

shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of

speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to

assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

|

|

|

Meanwhile the mainline churches continued to plunge deeper into Liberal- Fundamentalist infighting. In 1933 J. Gresham Machen, who had left Princeton Seminary and had founded Westminster Seminary in order to keep a more traditional evangelical Presbyterian theology alive and well, was finally forced by more progressive Presbyterians out of the Presbyterian denomination itself. He subsequently helped found the Conservative Orthodox Presbyterian Church, contributing to the movement of a number of individuals and congregations out of membership in the old mainline denomination. But it was a departure that gladdened the hearts of mainline Christians – who tended to be major supporters of the Social Gospel of good works as Christianity's central message to the country and the world. Furthermore, this departure of the Conservatives left the old mainstream Christian churches all the more clearly in the hands of Christian Liberals. Within the American church in general, Conservatives everywhere sensed that they were fighting a rear-guard action similar to the Presbyterians. And of course Liberals likewise felt that history and time were on their side – and that soon all reasonable people would be joining them in their modernizing religious camp. To forward-thinking Americans, their nation was entering enthusiastically another Age of Reason. Sadly, the more Liberal the churches became, the more they sounded like the Secular Humanists in the way they approached life. And as the mainline churches drifted further and further in this direction, they increasingly lost their strong, clear moral voice – once the moral bedrock of American politics. The churches were fast making themselves irrelevant. How ironic: it was their claim that by making themselves look more like the world they would enhance their influence in the world's affairs. But in fact, the end result was quite the opposite of what they were hoping for! This cultural movement would not occur as rapidly in America as it had in Hitler's Germany. But the nature of the movement would remain much the same: man, not God, would be looked to as the Savior of the rising world. In the midst of this religious transition one of America's greatest theologians, H. Richard Niebuhr, so tellingly described what was happening to the message of the American church: A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross. Fifield's Spiritual Mobilization movement

Yet outside of the world of theological academics there was some serious action underway to get the country back on course with God, and away from an increasing dependence on salvation by social design coming from FDR’s Washington experts. Los Angeles Congregational pastor James W. Fifield, Jr. – who had some of the same bold instincts as did once the greatest of the American capitalists. In the mid-1930s he founded Spiritual Mobilization, a grass-roots movement dedicated to getting the gospel of personal independence out to the nation, through the sermons preached from the pulpits of the movement’s extensive pastoral membership. Fifield was able to gain enormous financial backing from key business leaders so as to hold conferences, bring in speakers and publish materials to enlighten America’s clergy as to the role they needed to play in bringing the country out of its drift towards Socialism and back to America’s tradition of personal freedom, one that prompted personal initiative and responsibility, and ultimately personal success, something they were certain was mandated by God himself. This broad mix of Christianity with conservative political values during the last half of the 1930s (continuing through the 1940s and into the 1950s) brought thousands of pastors (and hundreds of businessmen) to active support of Spiritual Mobilization. Vereide's prayer breakfast movement

On another front, and also originating in the American West, was Norwegian-born Methodist minister Abraham Vereide's City Chapel program, bringing businessmen and local political officials (across the broadest religious and political spectrum possible, although basically Protestant in character) to "breakfasts" where extensive prayer would be offered – for the local community, the nation and the world. Vereide had earlier founded and led the Seattle operations of Goodwill Industries, a company focused on offering employment to those who had such disabilities that they would not likely find employment elsewhere. Vereide proved to be an outstanding organizational leader, building up the Seattle operation to involve tens of thousands of workers and supporters. But gradually he grew disillusioned with the failure of charity to change people's circumstances for the better, and resigned – to look for life's answers elsewhere. He too was a strong believer in personal initiative rather than governmental dependency. His next direction in life came when he visited San Francisco during the violent longshoremen's strike of 1934, and found himself invited to lead the local businessmen's association in prayer during those dark times. Then when he returned to Seattle (where the strike was also ongoing) he deliberately set up an early morning breakfast prayer meeting at his City Chapel for some of Seattle's business leaders, soon joined as well by some local politicians. These prayer breakfasts proved so encouraging to Seattle's demoralized business class that they continued their existence year after year, growing all the while. Here too in the early 1940s the war would only amplify the sense of need of such prayer gatherings, spreading Vereide's movement from city to city across the nation so that they would eventually become a key part of the American national religious and political scene, eventually including the president's annual Prayer Breakfast, started up in 1952.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges