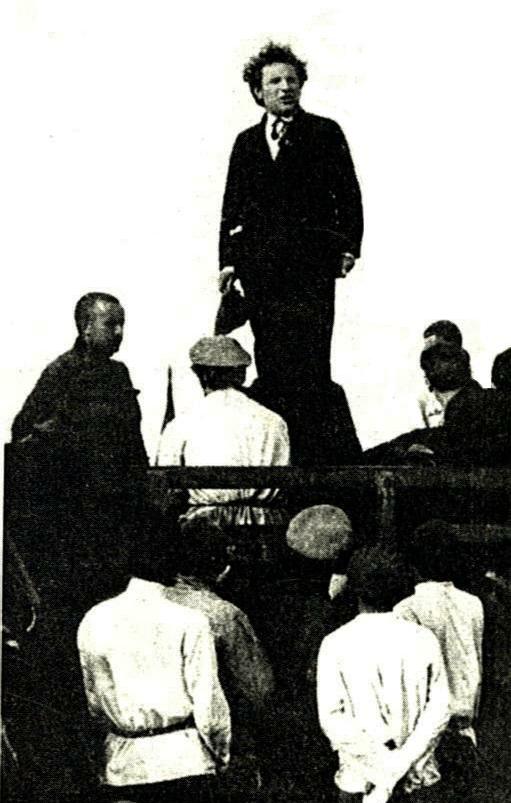

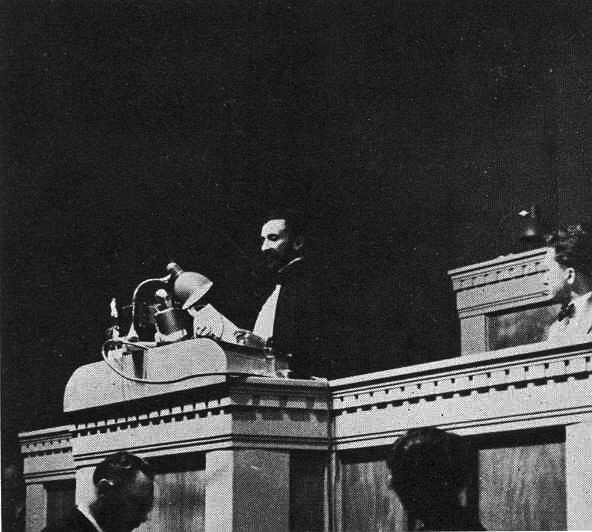

Benito Mussolini pitching

his Fascism to the crowds – 1934

Mussolini aping the German

goose step as he leads fellow Fascists on a march – 1938

Hitler and Mussolini – 1938

Hitler and Mussolini in

Rome

Hitler and Mussolini gaze

down upon a crowd at a Fascist rally in Rome – 1938

Italian infantrymen in Ethiopia – 1935

Ethiopian tribesmen – many

of whom defected to the Italians in the war

Ethiopians killed by Italian

bombing of their village

"It is us today, it will

be you tomorrow."

|

FRANCE AND

ENGLAND

SEEM TO HAVE LITTLE WILL TO STAND UP AGAINST THE RISING

DICTATORS

|

|

|

|

A divided France of the 1930s

In February of 1934 the growing antagonisms in

France between the political Left and the political Right – greatly

exacerbated by the Stavisky investment fraud which implicated many

Leftist cabinet members – erupted in the form of Paris riots, which

many thought was the prelude to an attempt at a Right-Wing political

coup. Order was restored to France. However, Left-Wing suspicions of

on-going Right-Wing Fascist plots, and similar suspicions by the Right

of Communist plots of the Left to take over France, split the country

into deeply hostile political groupings.

Besides the Left-Right deadlock over the

basic political path the country should take, the evolution of the

larger world of European politics, especially during the 1930s, made

French national politics even more complex. The French could not decide

which rising power to the East, Nazi Germany or Communist Russia, posed

the greater danger to Western, or at least French, civilization. Along

with this went wide disagreement on how to respond to Mussolini in

Ethiopia and the civil war raging in Spain (1936-1939).

In short – France really was not able to

get its act together at a time that it was supposed to be one of the

two major enforcers of the post war international status quo (the other

being Great Britain). Indeed, by the late 1930s France found itself

floundering in a deep domestic political war.

|

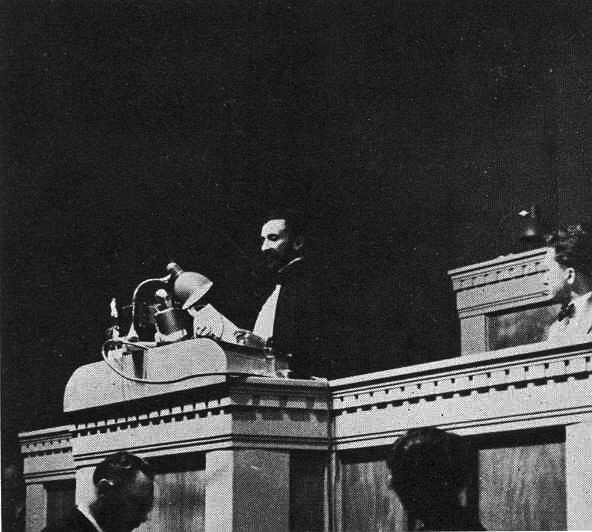

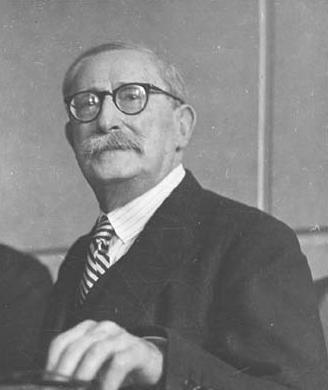

Léon Blum – French

Socialist Party leader and one of France's prime ministers

during the French leftist

"Popular Front" of 1936-1938

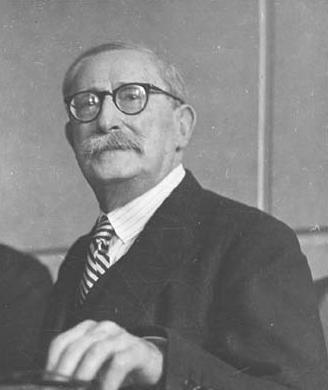

Édouard Daladier – head of the French "Radical" Party

and French Prime Minister

after the fall of the Popular Front in 1938 --

until just before Germany's

invasion of France in 1940

|

The British quest for peace – at any price

The Conservative Party leader Stanley Baldwin

dominated British politics during much of the period following the

Great War. Baldwin’s governance was characterized by a policy of

peace-at-any-price. He understood that the British did not want ever to

go to war again; that they expected him to keep them from diplomatic

entanglements and any military buildup, viewed at that time as largely

responsible for the Great War of 1914–1918; and that his first priority

as Britain’s leader was to get the country back on sound economic

footing.

Thus he cut back tremendously on British

military spending and strength at a time that Germany was rebuilding

its military power (happening even before Hitler took charge of Germany

in 1933) – in well-recognized violation of the terms of the Versailles

Treaty of 1919 and the Locarno Pact of 1925. Every effort was made by

Baldwin (and most British politicians and intellectuals) to excuse

Hitler's moves to remilitarize Germany – on the basis that Germany was

only compensating for the horrible injustices inflicted on Germany by

the now notorious Versailles Treaty.2

Thus Baldwin and fellow Conservative

Party member Winston Churchill (himself a former party leader) found

themselves constantly at odds over this issue of Great Britain's

pacifism in the face of German remilitarization. Baldwin viewed

Churchill as a war-monger who wanted to drag Great Britain into an arms

race and thus another war with Germany. Churchill viewed Baldwin as one

who invited German military adventurism by the obvious lack of English

resolve to stop Hitler before he became so strong that there would be

no way to block his military ambitions.

Basically, Baldwin was working out of the

spirit of the moment, of the times he lived in. Churchill was working

out of a longer sense of British history – and its long-standing role

as balancer of power on the European continent (as for instance in the

days of Napoleon in the early 1800s). History would soon be the judge

of which of the two had it right.

2The

spirit of total pacifism was so strong in Britain that not only did the

British Communist and Labour Parties on the Left denounce British

remilitarization but also in 1933 the Oxford Union debated the issue of

British intervention in the Japanese takeover of Manchuria, producing

(with a vote of 275 to 153) a final resolution declaring that "this

House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country." The

resolution brought on much debate not only in Britain, but around the

world. Churchill was loud in his contempt for this resolution!

|

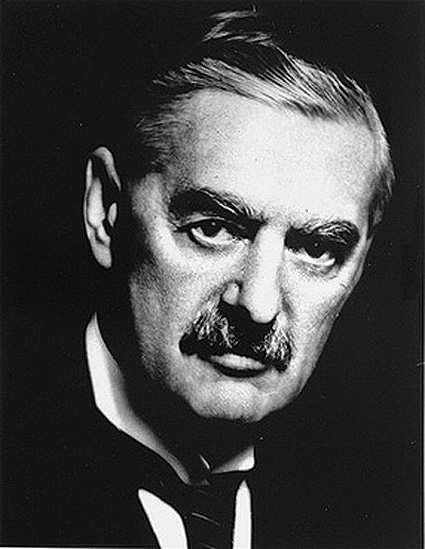

Stanley Baldwin (Conservative

Party) – British Prime Minister – 1923-24; 1924-29; 1935-37

|

Chamberlain's "appeasement" policy

Then in May of 1937 an exhausted Stanley Baldwin

stepped down and the new Conservative Party leader Neville Chamberlain

became English Prime Minister. Whereas Baldwin had been a pacifist,

Chamberlain was actually rather pro-German. As the 1930s developed, it

appeared that Great Britain too was facing a choice of which of the two

growing military powers to the East, Communist Russia or Nazi Germany,

was the greater threat to the peace of Europe (and thus also the

world). Chamberlain took the view that it was the Russian Communists

that posed the greater danger, and a policy of "appeasing" Germany's

Hitler (and Italy's Mussolini) would bring the nations of West and

Central Europe into a broad anti-Communist/anti-Russian front.

But Great Britain (and Europe) would soon discover the shortcomings of the appeasement approach to Hitler and his doings.

|

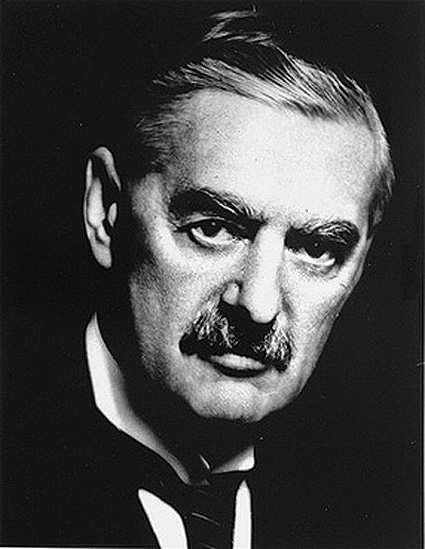

Neville Chamberlain (Conservative

Party) – British Prime Minister – 1937-1940

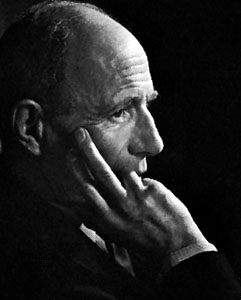

Edward

Frederick Lindley

Wood, 1st earl of Halifax – British Foreign Minister – 1938-1940

also an "appeaser" toward

Germany

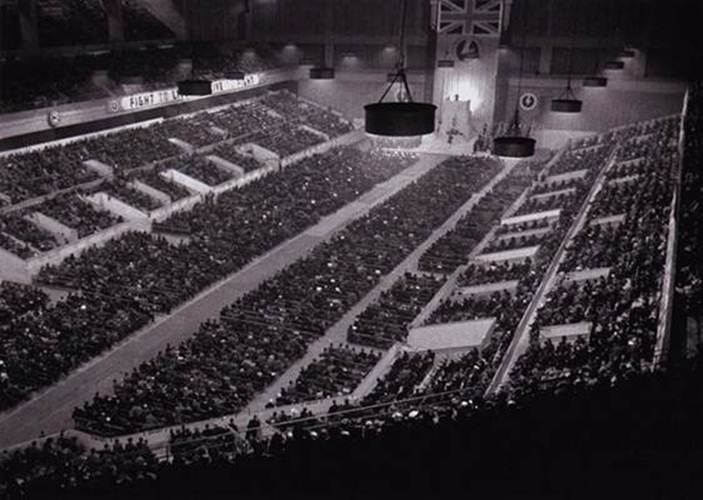

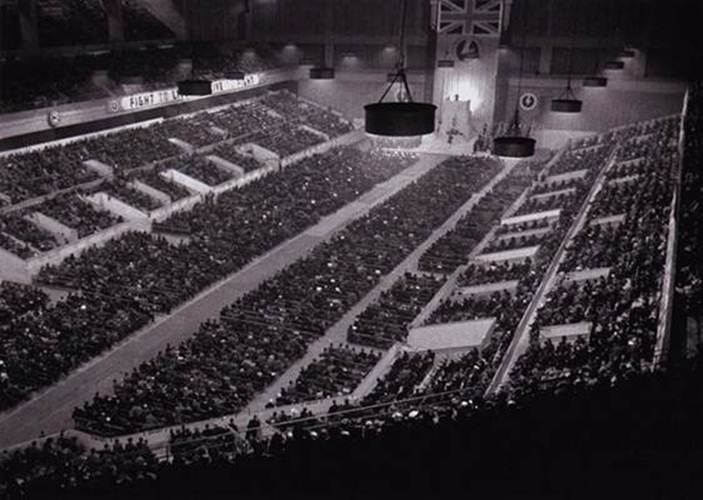

The British Union of

Fascists

and National Socialists Rally – London, 1936

One of the largest public meetings held in

Britain in the 1930s ... and indicative of the mixed

sentiment of the

British

about which way to turn in the face of continental

developments

|

THE SPANISH CIVIL

WAR

(1936-1939)

|

|

|

|

Although Spain was a Constitutional Monarchy (like

Great Britain and most of the rest of the European continent) the

country had actually been run by a system of local bosses (caciques)

with little interest in turning Spain into a modern society. Spain

itself was highly divided as to the direction it wanted to go,

especially after the Great War, which Spain stayed out of but which

benefitted a small group of industrial entrepreneurs who sold goods to

the combatants. The vast and highly traditional countryside (strongly

Roman Catholic and even semi-feudal in mentality) was greatly alienated

by this small intrusion of modernity into a society still romantically

attached to the glorious past of the 1500s, a past that was very

unlikely to ever return. Then there were the new industrial workers who

grudgingly took their place in Spain's factories, who felt a bit of

kinship with the Russian workers who similarly had moved abruptly from

feudalism to modern industrial society – led by Communist idealists

(the Bolsheviks). In short, Spain was a confused and highly divided

society.

Into that confusion stepped Spanish

General Primo de Rivera – who seized power in 1923, and forced economic

and social discipline on Spain, settling things down a bit (and

eliminating the caciques) – but whose rule gradually began to draw

strong criticism from impatient modernizers who felt that his

Mussolini-like grip over Spanish society (and the Spanish monarchy that

supported him) was only serving to block real social progress.

Ultimately both Rivera and King Alfonso, tiring of the situation, in

1931 called for a referendum on Spain's future. The results went in

favor of a Republican government, and Rivera stepped down and the king

abdicated.

But the Republican government's move to

secularize Spain's Catholic culture (undercutting the Church's role in

the country's schooling and cultural disciplines, such as its stand on

marriage and divorce) served only to deepen the cultural division that

split Spain into two hostile groups, the Republicans concentrated

heavily in urban Spain – actually bitter about the slowness of the

social reforms (and increasingly of a Communist or anarchist frame of

mind) – and the more rural Nationalists who clung desperately to a

clearly dying traditional Catholic Spain.

Back and forth power swung in the

national parliament (the Cortes) until by mid-1936 the battle had moved

to the streets in the form of fighting between the two groups: the

Conservative Falangists (backed by a very conservative Spanish

military) and the proto-Communist Republicans (supported by 200,000

Asaltos or fighters). This was the signal for General Francisco Franco

Bahamonde to leave his position in Morocco with accompanying

Nationalist troops and head to Spain, to fight the Republicans. At this

point the very bloody Spanish Civil War broke out.

But this civil war did not actually

remain much of a civil war. Instead it turned itself quickly into a

test run of the superpowers, especially Germany and Italy which

intervened on Franco's side, to try out their new military products and

strategies (dive bombers, for instance). At the same time, Stalin sent

a huge number of advisors to help the Republicans against Franco – as

did also France and Britain, although only on a very small scale.

Volunteers poured in from America serving on one side or another,

Hemingway, for instance, actually serving with the Republicans –

building his 1940 novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, on his own experience in the war.

Feelings ran very hot on both sides of

the war, both sides destroying villages (and killing villagers) caught

in the crossfire. And major atrocities occurred: Leftist Republicans

killing priests and raping nuns – and the Nazi allies of Franco

leveling the town of Guernica as practice in developing divebombing

techniques that would later be used by Hitler in his conduct of

Blitzkrieg (Lightning War).

Little by little Franco's Falangists

(with a lot of help from the Germans and Italians) were able to gain

ground against the Republicans, until in 1939 Madrid was finally taken

by Franco, and the war came to a halt.

Spain was devastated. And it

would have presiding over it a dictator determined to shape Spain

exactly as he himself determined, all the way up until his death

decades later (1975).

Also, Spain was exhausted, and

in no hurry to get involved in another war (they would also sit out

World War Two).

But everything that pointed to the tragedy that

was about to break out in Europe was contained in those events of

1936–1939. The Spanish Civil War, in fact, was simply a dry run

on the larger war that Hitler had planned for Europe. And the

responses of all the major players to the events focused on Spain would

resemble very closely how the diplomacy and military development would

occur as events leading up to World War Two. But few understood

this at the time, especially the British and French who continued to

hope that they somehow knew the formulas for keeping the peace in

Europe. Spain taught them nothing.

|

Francisco

Franco – leader of the Falangists or Nationalists

... who also absorbed the traditionalist Carlists into his organization

Republican militia

closing in on Nationalists barricaded in the ruins of the Alcazar in

Toledo

The famous Alcazar in Toledo,

where the Nationalists held out for days

against the Republicans,

was razed to the ground – August 1936.

On

September 27, Franco's Nationalist forces reached Toledo and drove the

Republicans off – thus ending the siege – and making Franco the hero

of the Nationalist cause. Two days later Franco proclaimed

himself Generalissimo and shortly thereafter took the title as Head of State.

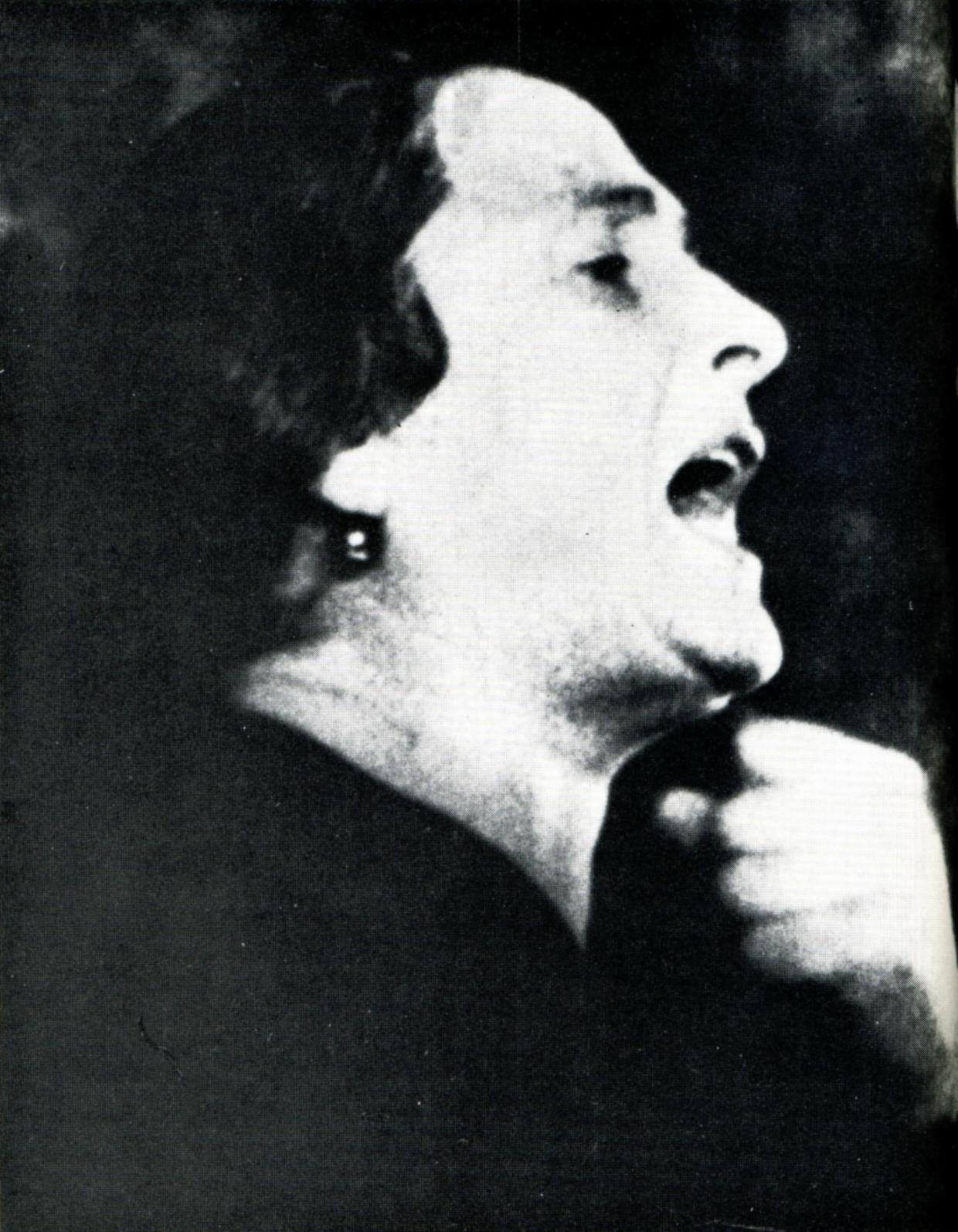

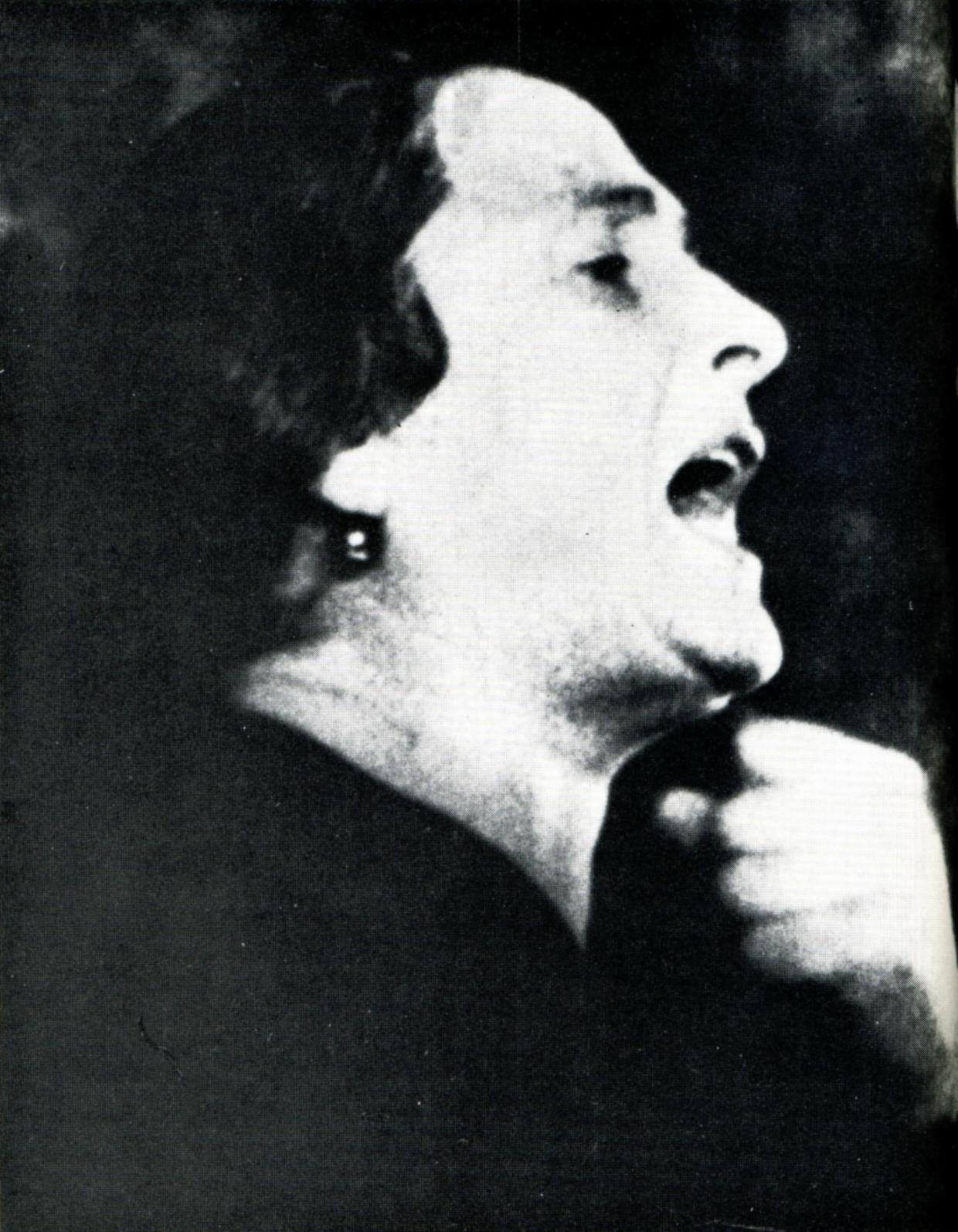

When Seville fell to the Nationalist troops, 200,000 workers (heavily

Communist) were stirred to counter-action in Madrid by the passionate

Dolores Irarruri ("la Pasionaria"). This was a call to arms of

those loyal to the Leftist Republic.

|

Communist militiamen during

the early stages of the Civil War

Republican International

Brigade troops at Casa de Campo on the western outskirts of Madrid

during the battle against

Franco's invading Nationalist forces – November 1936

Spanish loyalist (Republicanist)

women militia

Dolores Ibarruri - "la Passionaria" stirs Communists to action

in support of the Republican cause

Carlist requetés receive

the benediction before an assault on Irun – 1936

|

International Involvement

Seeing a fellow Popular Front Government in Spain under threat by

Rightist forces, Leon Blum's Leftist Popular Front government in France

quickly sent 30 French planes and pilots to help the Republican

government crush the rebels. But in turn, Franco called upon the

Nazis of Germany and the Fascists of Italy to come to the aid of the

Nationalists' cause. By the end of July German and Italian

planes were arriving in Morocco to assist Franco in his revolt against

the Republican government of Spain. Thus the Spanish civil war became

from the very outset an international issue.

However, the Spanish Civil War became an international issue not just because

foreign countries wanted to help out one side or the other in the

struggle – but because the war in Spain gave a number of countries the

opportunity to develop and test larger political, military and

diplomatic strategies of their own.

Battle of Guadalajara (8 March – 23 March 1937)

Mussolini's

Italians and Franco's Nationalists combined forces to

attack Madrid from Guadalajara. Vastly outnumbering the

Republican forces, the Italians and Nationalists were at first

successful in taking one small town after another. But bad

weather – and the arrival of the International Brigade stiffened the

Republican defense (though they were still outnumbered 2 to 1).

The Republican air force was also operating from concrete runways –

whereas their opponents were grounded with an airstrip of mud.

Gradually the Republicans began to push the Italians and Nationalists

into full retreat. The Italians lost some 6,000 men in the action

– and Mussolini lost a huge amount of prestige, for he had personally

organized the Italian effort in order to gain the prestige of what he

originally thought was going to be a grand victory.

|

A Savoia-Marchetti SM.81

during a bombing raid in the Spanish Civil War

|

The bombing of Guernica, April 26, 1937

The bombing of Guernica was an aerial attack by the German Luftwaffe

squadron known as the Condor Legion against the Basque city of Gernika

(Spanish: Guernica).

|

Guernica, after the bombing

of April 26, 1937

Italian troops entering Guernica

after the bombing

Pablo Picasso – Guernica – 1937

The huge mural was produced

under a commission by the Spanish Republican government to

decorate the Spanish Pavilion at

the Paris International Exposition (the 1937 World's Fair in

Paris)

Francoists burning Basque

secular school textbooks in Guernica

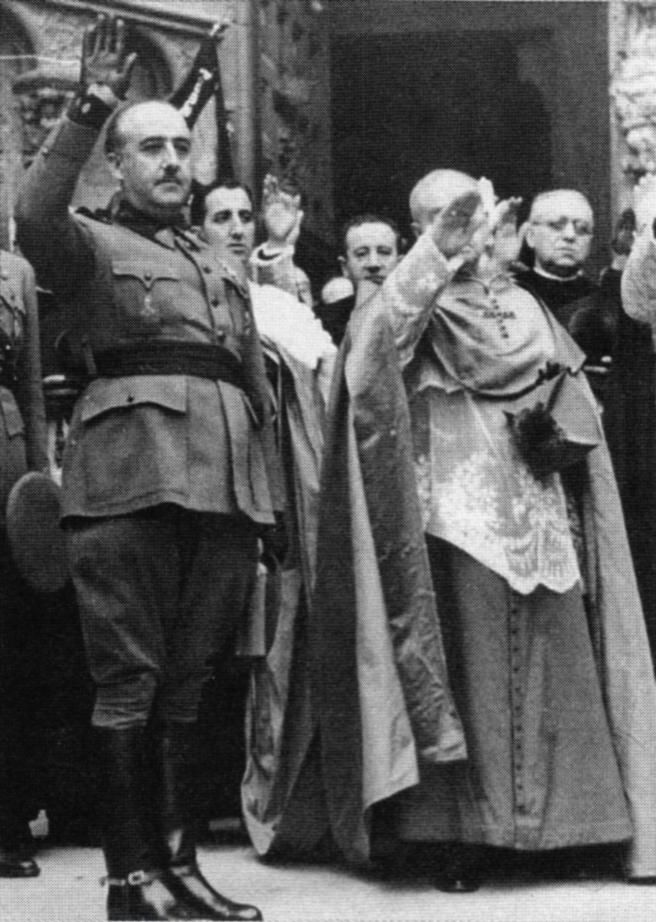

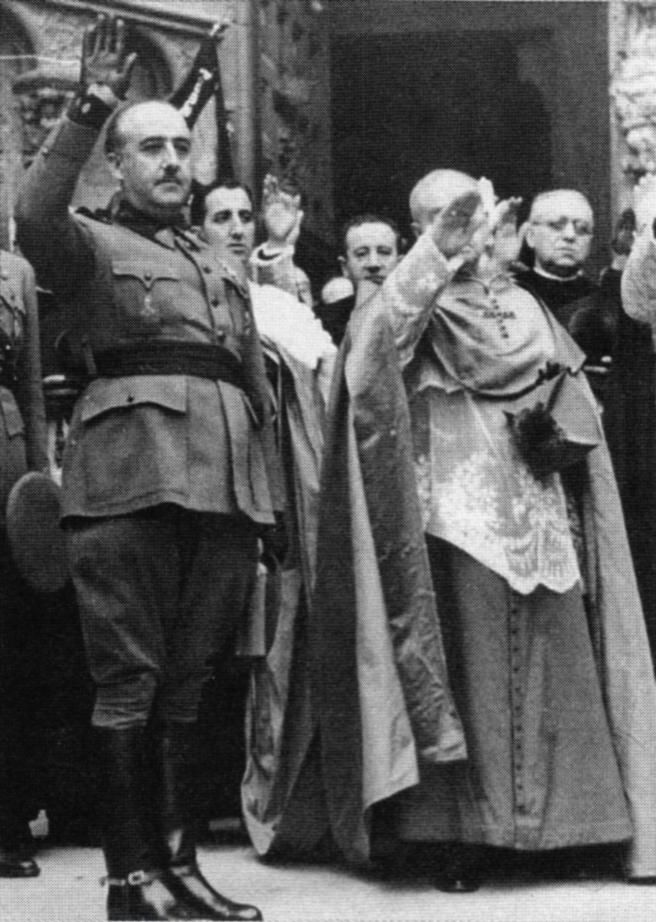

The Catholic Church offers its full support to Franco

in his overthrow of the democratically elected

Spanish Republican government

The Spanish Catholic Church

demonstrating its support of the Falangist (Fascist)

General Francisco Franco – November 1938

Generalissimo Francisco Franco

reviewing his Falangist troops after taking Madrid in 1939

|

JAPANESE

IMPERIALISM

IN ASIA

|

|

|

|

Japan had come to consider itself one of the great

world powers as the 20th century got underway, having modernized its

army and navy to the point that it was able to defeat Tsarist Russia in

a Siberian war fought in 1904 and 1905. Also, although the Great War

(1914–1918) was essentially a European war, Japan played a part as an

Asian ally of the British and French – and was rewarded accordingly by

the formal recognition on the part of those victorious powers of the

Japanese takeover of German colonies in the Pacific.

America, of course, was wary of Japanese

broader interests in Asia (the Philippines was an American protectorate

defended by a number of American troops posted there). But in general

Japanese-American relations remained somewhat friendly, although the

Japanese were insulted by America's 1924 Immigration Act, which reduced

greatly the number of immigrants allowed to come to America – virtually

excluding all Japanese.

But the Japanese were making an effort to

move closer to the ideal of democracy – democracy supposedly having

proved itself the stronger social system in the recent war with

autocracy.

However with the onset of the depression,

democracy was not looking so impressive, and the Japanese military

group within the Japanese Imperial Cabinet began to take a scornful

attitude toward the Japanese pro-democracy civilian politicians – who

had agreed to internationally determined formulas of naval and military

disarmament – the military party pressing instead for a military

buildup of both the army and the navy. Indeed, radicals within the

Japanese military were calling for a revival of Shinto, a somewhat

mystical philosophy stressing the virtue of military valor or bushido –

even the glory of death in battle. For some (especially the younger)

Japanese soldiers, Shinto and its bushido ethic formed for them an

intoxicating ideal.

By the early 1930s civilian leaders were being assassinated – and cabinets were being turned over with destabilizing rapidity.

Also in 1932 young officers in the

Japanese occupation army in Manchuria (northeastern China) staged a

fake crisis and used the event to simply take full control of the

Chinese province and set up a puppet government there. The Japanese

Emperor Hirohito did not seem to object – and the civilian government

seemed unable to undo the takeover (very popular with the Japanese

people).

|

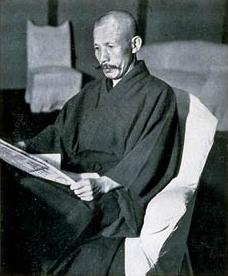

Japanese Prime Minister Makoto

Saito – 1932-1934

The Imperial Pictorial,

vol.2

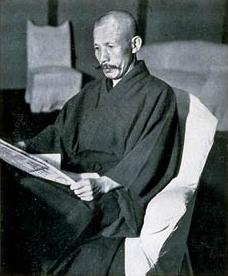

Japanese War Minister Sadao

Araki

The chief theoretician for

the Kodoha ultra-nationalist Japanese

Time 1933

Japanese Prime Minister Okada

Keisuke – 1934-1936

National Diet Library archives,

Tokyo

|

World War Two begins in China (1937).

Tensions began to mount in the Chinese North

between the Japanese Imperial government and the Chinese Republican

government under President Chiang Kai-shek, tensions which exploded

into full battle between the two countries in July of 1937 over a minor

incident at a bridge along the northern border. Using this incident as

an excuse, the Japanese invaded with full force into China – by the

army from the north and by the navy along the east coast. In short

order, the Japanese overran the major cities of the Chinese coast,

bombing the civilian population in Shanghai and worse, raping and

pillaging the Chinese in their capital city of Nanking (Nanjing). But

the Chinese government simply retreated into the huge Chinese interior

– from there to conduct an ongoing resistance movement against their

Japanese occupiers.

Thus, World War Two in the East Asian

theater had actually begun, as the first chapter in this very barbaric

story. Yet America, though deeply shocked by the stories of the

Japanese atrocities committed against the Chinese, chose to look away

rather than get involved.

But developments in Europe, plus an

alliance between the Japanese and Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's

Italy, would eventually change that American stance – dramatically.

|

The "Luo Kuo Chiao Incident"

of July 7, 1937

When the KMT army refused to allow

Japanese troops to cross the bridge in search of a missing

soldier, shooting broke out between the Japanese

and Chinese – as the first blow of the war

Chinese troops defending

the Luguo Bridge

Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi)

announcing the KMT's policy of

resistance against Japan

at Lushan on July 10, 1937,

three days after the Battle

of Lugou Bridge.

Japanese troops marching

through the rubble of a village near Hankow

Japanese generals toasting

their victory at Hsuchow (Xuzhou)

Shanghai – bombed by

Japanese

One of the last humans left

alive after intense bombing during the Japanese

attack on Shanghai's South

Station. August 1937.

A Japanese tank rolls onto

the Shanghai-Nanking railroad

Japanese troops in the ruins

of Shanghai – 1937

Nanking 1937: The ceremonial

entrance of the Japanese forces into the city of Nanking

(Nanjing) after the city

fell to the Japanese on December 13, 1937.

Nanking 1937

“Ten Thousand

Corpse Ditch”, where bodies of mass execution victims were

dumped.

(as many as 300,000 unarmed

civilians may have been executed over a 6-week period,

though the numbers are hotly

debated between the Japanese and Chinese even today)

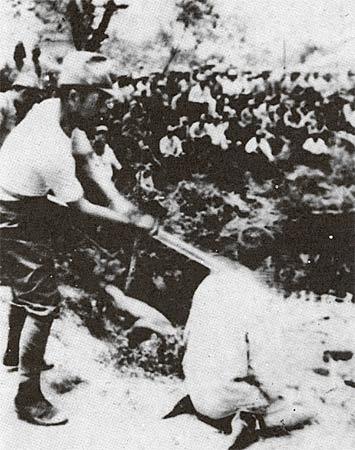

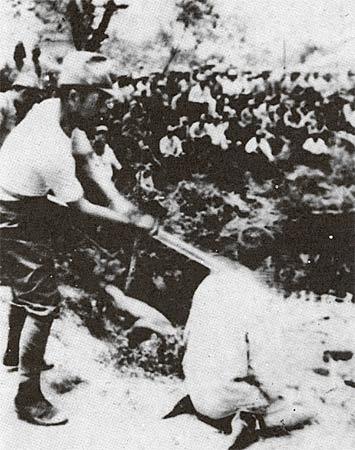

Nanking 1937: rape

and massacre of civilians

Nanking 1937: A photo

first published by Look magazine in 1938.

It shows Japanese army recruits

at a bayonet drill, practicing on Chinese prisoners.

Nanking 1937: Japanese soldier

and beheaded Chinaman

Japanese soldiers celebrating

the capture of Hankow

(temporary Chinese capital after the fall of

Nanking)

|

THE EXPANSION OF HITLER'S NAZI EMPIRE

GOES UNCHALLENGED

|

|

|

|

The logic of Chamberlain's appeasement policy soon

developed a life of its own, especially as Churchill continued to

challenge Chamberlain concerning the grave Nazi danger. Churchill, once

an avid anti-Communist, was taking the view (in the press and on the

radio as well as in Parliamentary debates) that with Hitler's rise to

power in Germany, the Nazi's were quickly becoming the greater threat

to Great Britain's security than even Stalin's Communist Russia.

Promises that each of Chamberlain's many

concessions to Germany would be the last were constantly broken by

Hitler – with each retreat by Chamberlain rationalized as necessary

steps in pacifying Hitler. Actually, each retreat only made the

dictator hungrier for German expansion. Sadly, Chamberlain (like

Baldwin) talked himself into believing that what he was doing – using

diplomatic Reason rather than brute Power – was protecting (rather than

undermining) the peace of Europe.

The German Anschluss with Austria (March 1938)

One

of Hitler's major political goals was

uniting German-speaking Austria with his German Nazi Reich (a move that

was forbidden by the treaties of 1919). He brought both his

cabinet and

his military in line with his policy (replacing leaders in both) and

then pressured the Austrian government to install more Nazis in their

cabinet. Meanwhile he began pushing Chamberlain's government to

allow

the unification of Germany and Austria, in theory as part of a stronger

defense against Communist expansion in East Europe. When

Chamberlain

seemed to be yielding, British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden

resigned. But Austrian Prime Minister Kurt von Schuschnigg

refused to yield,

finally arranging to have the Austrians determine the matter themselves

with a national plebiscite. But two days before the scheduled

election

Hitler threatened to send his troops into Germany if Schuschnigg did

not resign (which he did) and have him replaced by the Austrian Nazi

leader Arthur Seyss-Inquart (March 12, 1938). Then Seyss-Inquart

in

turn invited the Nazis (already moving across the border at this point)

to take over Austria to "restore order." A month later a highly

manipulated national plebiscite was held in Austria, producing the

highly unlikely result of a 99.7 percent approval of the Anschluss

("closing together" or '"connecting") of the two countries into a

single Germany.

The reaction of the enforcing powers of

the treaties forbidding such a union (principally Britain and France)

was weak in the extreme. Chamberlain, sensing the dangers of such

further expansion into other German areas around Hitler's Reich

(principally Czechoslovakia and Poland) did nothing, but did promise

that he would support Germany's neighbors against any further expansion

by Hitler and his Nazis.

|

Hitler's grab of Austria (the German

Anschluss)

German police entering the

city Imst in Tyrol/Austria on 12 March 1938.

Nazi troops being greeted

by Viennese as they move in to effect the Anschluss with

Austria

"Hitler accepts the ovation of the Reichstag

after announcing the 'peaceful' acquisition of Austria."

It set the stage to annex the Czechoslovakian

Sudetenland,

largely inhabited by a German- speaking

population." Berlin, March 1938

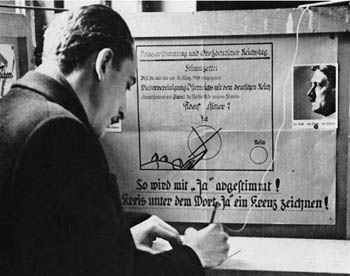

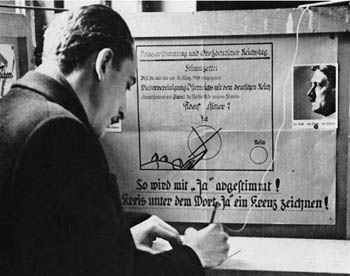

The referendum on 10 April

1938 on the Anschluss in Austria

Propaganda even in the voting

booth

with a poster instructing

voters how to vote "Ja", i.e. "Yes".

Hitler seizes Czechoslovakia ... in stages

|

Chamberlain would have the opportunity soon enough

to make good on his promise – and once again back down in the face of

Hitler’s aggressive moves. Hitler now set his eyes on the Germans

living in the mountainous borderlands of Czechoslovakia (the region

known as Sudetenland). Hitler began to claim loudly that the Czechs

were mistreating the Germans of the Sudetenland (totally untrue) and he

was thus forced to have to deal with this situation. However,

Czechoslovakia’s military defenses (aimed primarily against Germany,

but also the new Poland) were well dug in there, and Czechoslovakia’s

battle-ready forty infantry divisions would have offered very effective

and very embarrassing resistance to any aggressions on the part of

Hitler.

But to avoid a mounting international

crisis, Chamberlain agreed to meet in September (1938) with Hitler (and

Mussolini) in Munich, to seek a peaceful resolution to this (non)

crisis, not knowing that officers in the German high command were

secretly making plans to depose Hitler before he dragged the country

into an unwanted war.

Then as a result of the discussions held

in Munich concerning this Czechoslovakian crisis (to which the

Czechoslovakian leadership itself was not even invited), Chamberlain

was pleased to offer the world a peaceful solution, one that would

avoid dragging Europe into another war. Hitler would be allowed to take

over the Sudetenland (and Czechoslovakia's mountain border defenses),

with Hitler's promise that this was all of Czechoslovakia that he

wanted.

So happy was the European world (except the

outraged Czechs, whose beloved President Edvard Beneš resigned rather

than agree to the terms forced on his country) that Chamberlain had

"saved Europe from another war," that talk grew of awarding him the Nobel

Peace Prize!

And most tragically for the world, it also

forced the German High command to cancel its proposed removal of Hitler

– as Hitler's acquisition of Sudetenland again made him the supreme

hero of the German people.

|

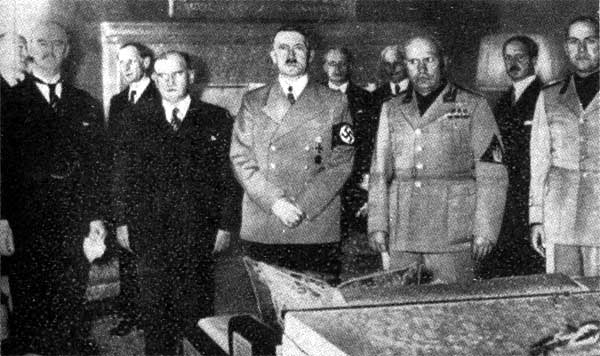

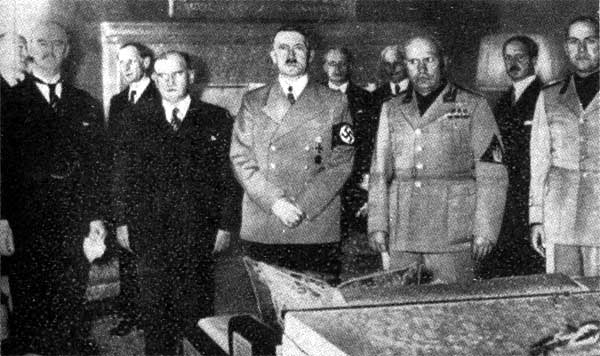

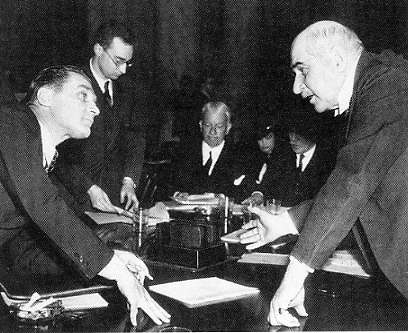

Before signing the Munich

agreement. From left to right: Chamberlain,

Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini,

Ciano

Adolf Hitler and Neville

Chamberlain after the Munich Agreement

which gave Czechoslovakia's defensive borderlands to

Hitler

Edvard Beneš – President

of Czechoslovakia

He was not invited by either

Hitler or Chamberlain to participate or have a voice

in the dismembering of his

country by both enemy and "allied" nations

Neville Chamberlain, on his

return from meeting with Hitler,

announcing "Peace for our Time" – Sept.

30, 1938

Appreciative crowds hail

the British Prime Minister for having brought them "Peace in Our

Time."

Ecstatic Sudeten women greeting

arriving German troops

|

Hitler completes the absorption of Czechoslovakia

Of course Hitler had no intention of

keeping his promise to Chamberlain, and in March of 1939 – at the

"invitation" of Czechoslovakia's new leadership (the browbeaten

President Hacha) – Hitler sent his troops to take over all of

Czechoslovakia.

The world was shocked, but again did

nothing. Chamberlain again repeated his promise that he would protect

Germany's neighbors (Poland the next obvious target) – with the threat

of a declaration of war against Germany if Hitler were to make such a

move.

But by this time few believed that

Chamberlain would – or even at this point could – deliver in a

meaningful way on such a threat.

|

A weary Emil Hácha,

recently elevated to Czech presidency, is brought to Germany

to be browbeaten by Hitler

into the surrender of his country to Nazi control – 1939

Germans arriving in Prague

in front of the Hradčany Castle

March 15, 1939 – Shocked

and angry Czechs reacting to the Nazi takeover

of the whole of Czechoslovakia

and its capital, Prague

"If Hitler were to attack what would

the

Pacifists do?"

French grow increasingly

concerned about Hitler

|

THE NAZI ASSAULT ON THE JEWS INTENSIFIES

|

|

|

Jewish persecution begins

in Austria as Jews are made to scrub

pro-Austrian slogans from streets – March 1938

|

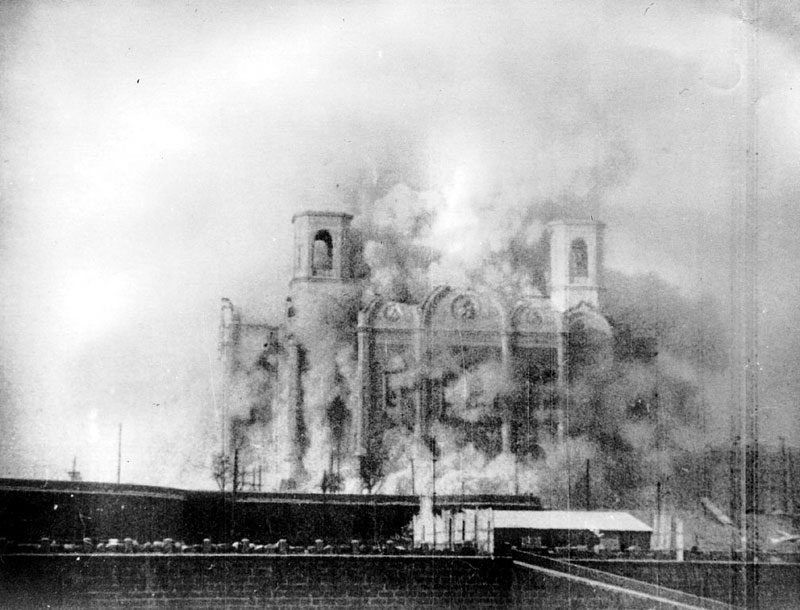

Kristallnacht – November 9, 1938 (The night of broken glass)

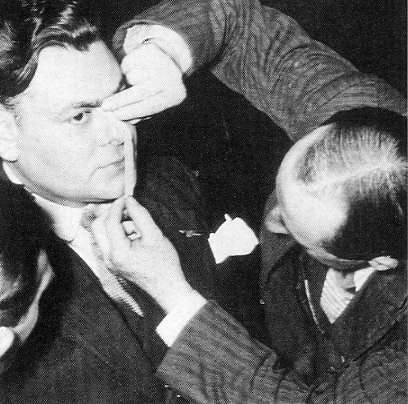

November 7, 1938 – Herschel Grynszpan, a young Polish Jew in Paris,

shot and killed the German 3rd secretary in the embassy there,

providing the Nazi government the excuse to retaliate 2 days later

against Jews everywhere in a night of terror known as Kristallnacht –

for all the glass windows of Jewish stores destroyed. Synagogues

were burned, 7,500 shops were wrecked, perhaps as many as a hundred

Jews were killed, thirty thousands were arrested and fines totaling a

billion marks were levied on the Jews. Also all the insurance

money paid to the Jews for the damage of the Kristallnacht (5 million

marks) was confiscated by the government.

|

Kristallnacht – the day after (November

10,

1938)

Kristallnacht – November

1938

Jewish arrests in

Baden-Baden, Germany (November

10), as a follow-up on

Kristallnacht

Jews being led

away (November

10)

to Dachau,

Buchenwald or Sachsenhausen

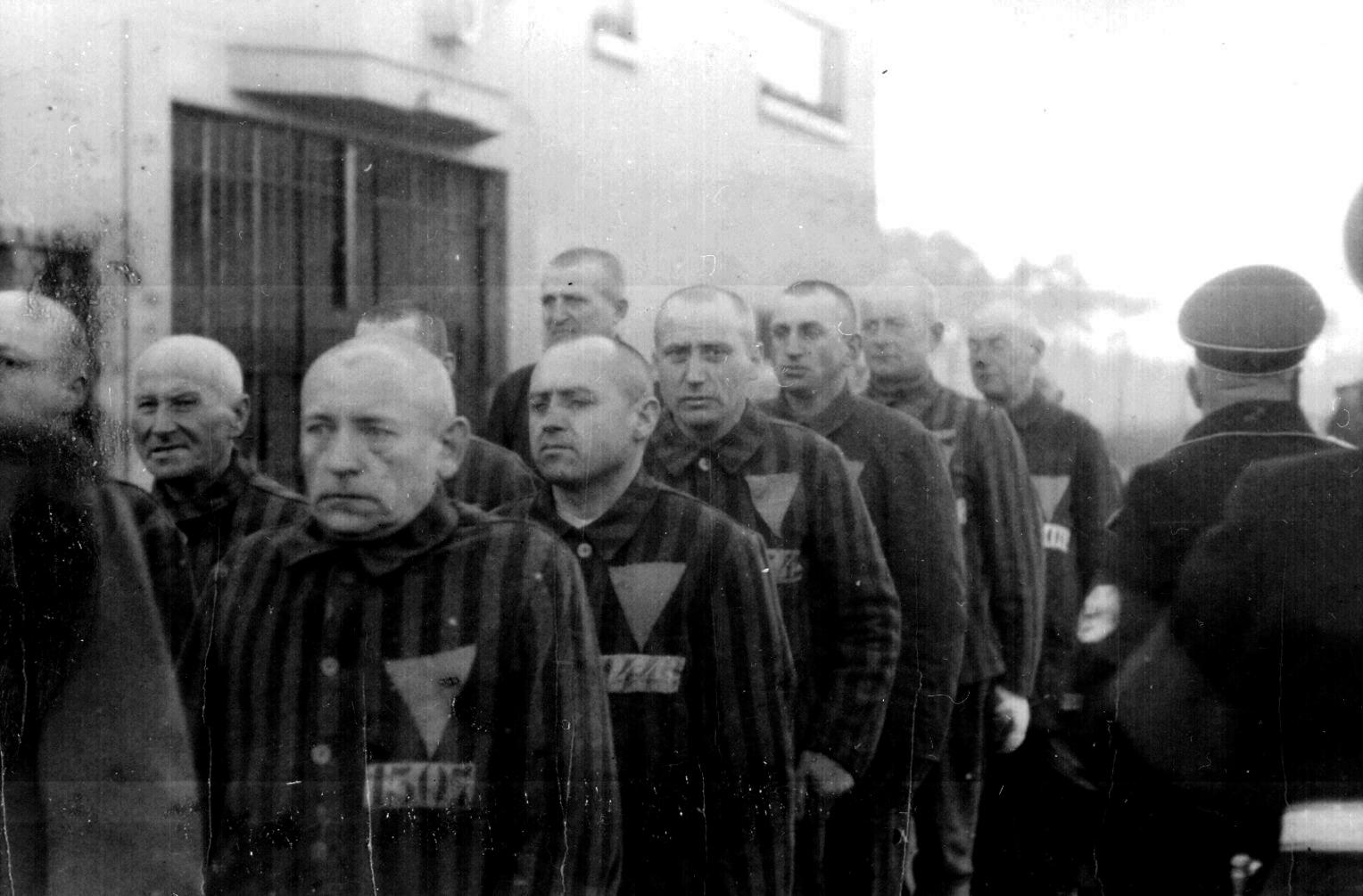

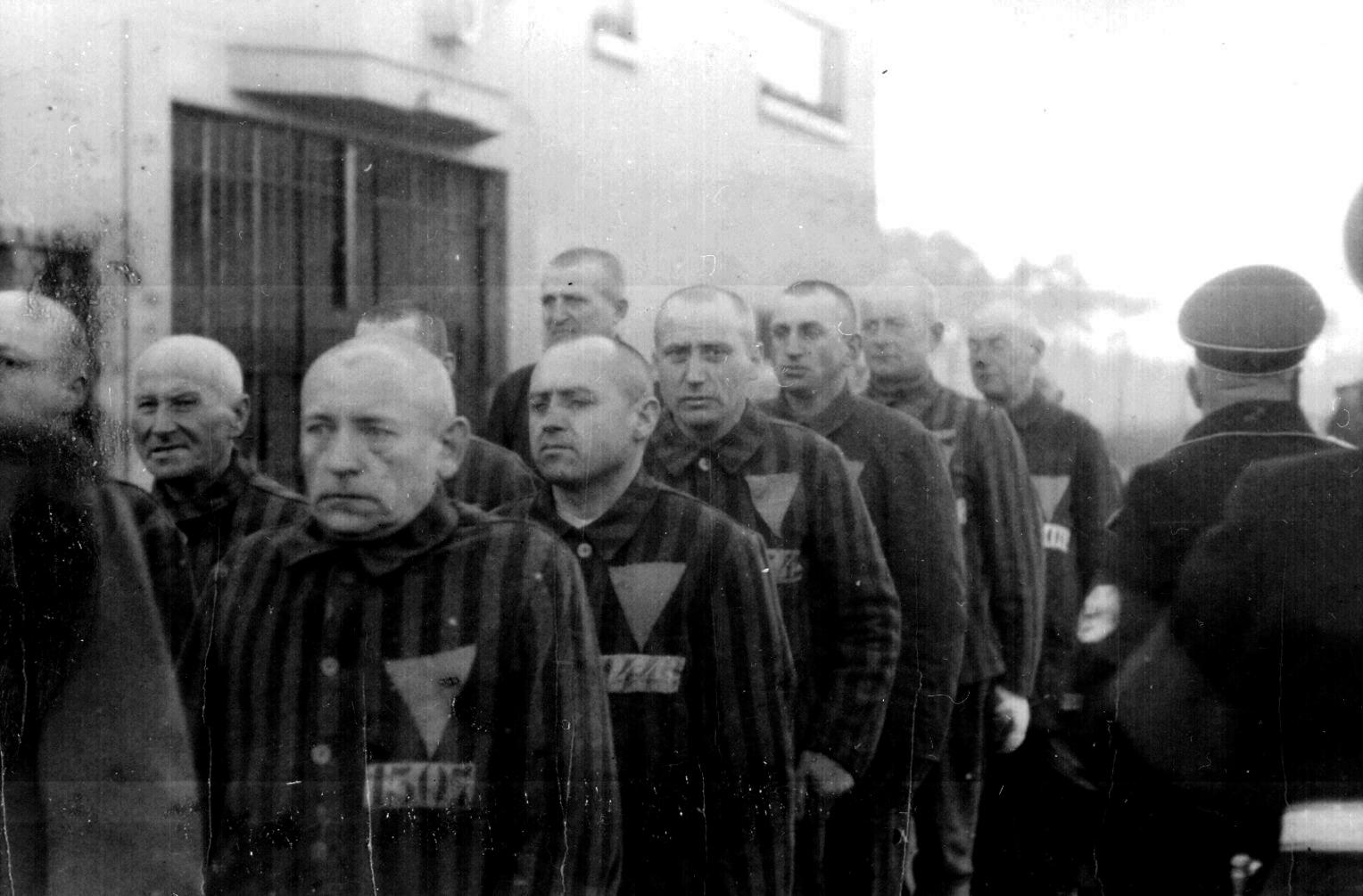

Concentration Camps

Jews arrested during

Kristallnacht line up for roll call at the Buchenwald Concentration

Camp

Prisoners in the concentration

camp at Sachsenhausen, Germany, December 19, 1938.

National Archives

242-HLB-3609-25

The attractiveness of the European

Dictators

The attractiveness of the European

Dictators

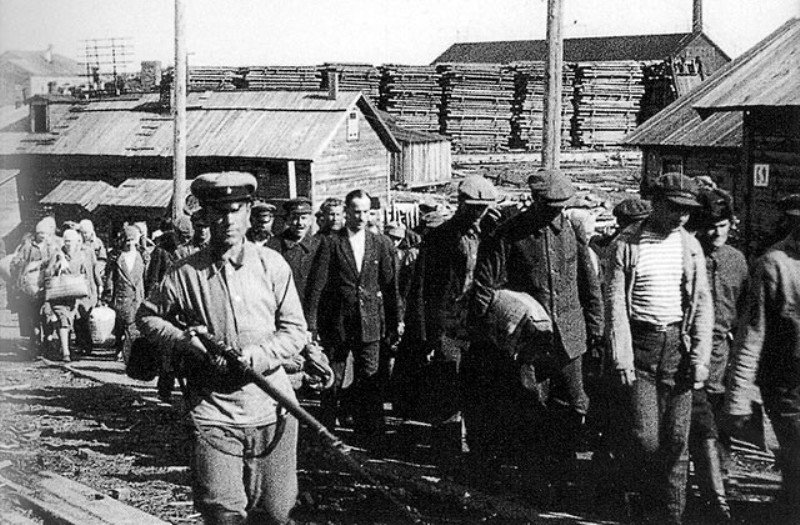

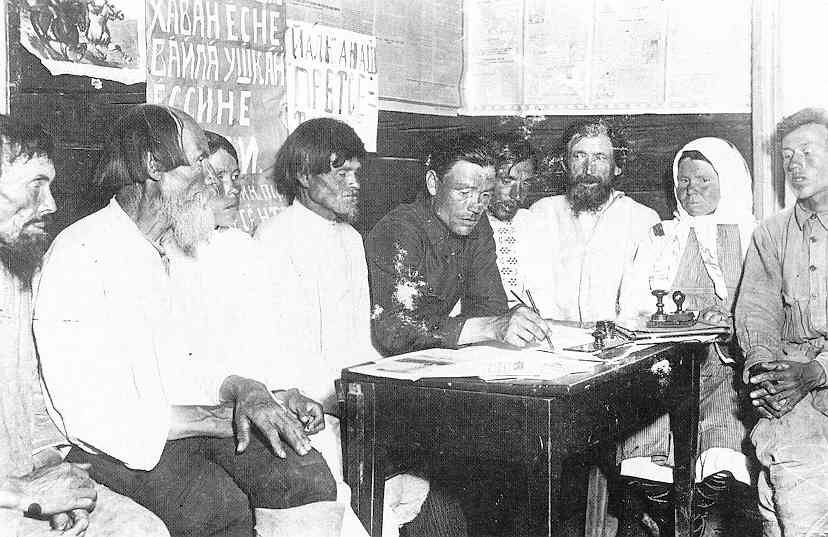

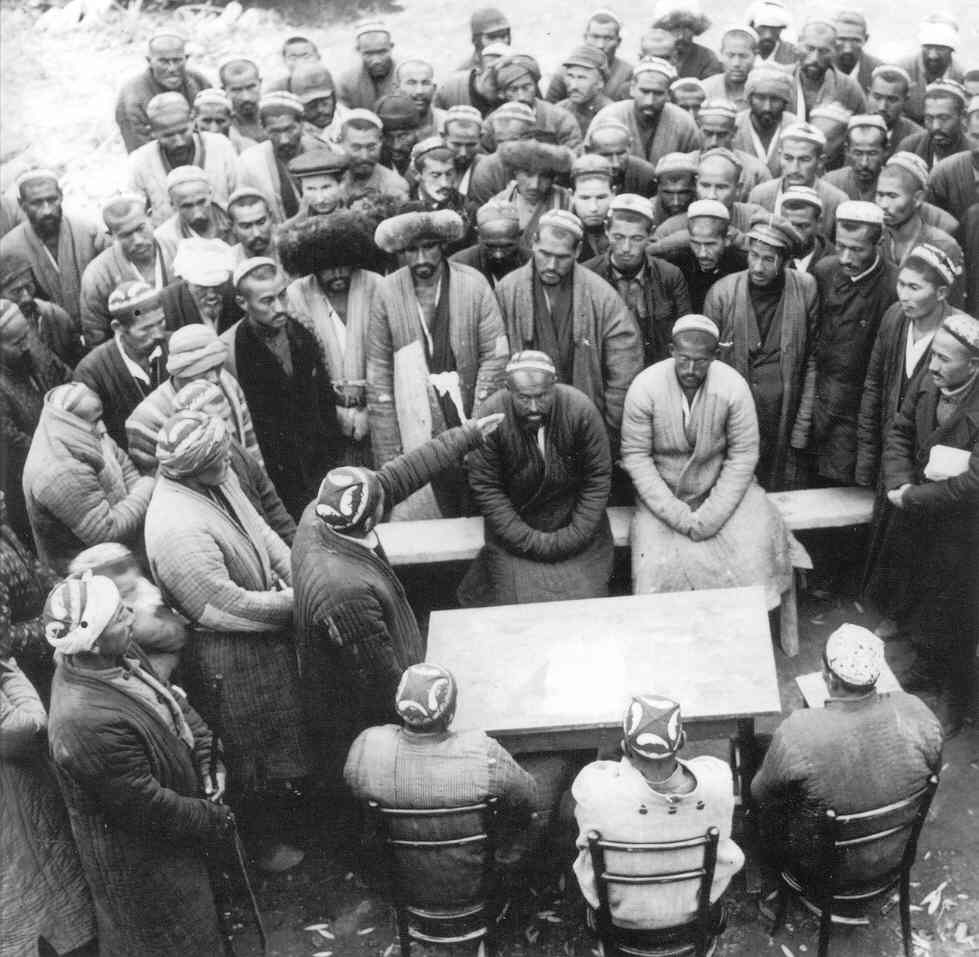

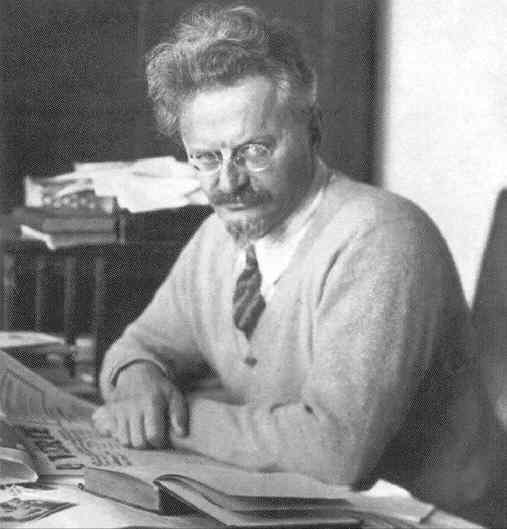

Stalin's Communist "command" economy

(or "state

capitalism")

Stalin's Communist "command" economy

(or "state

capitalism")

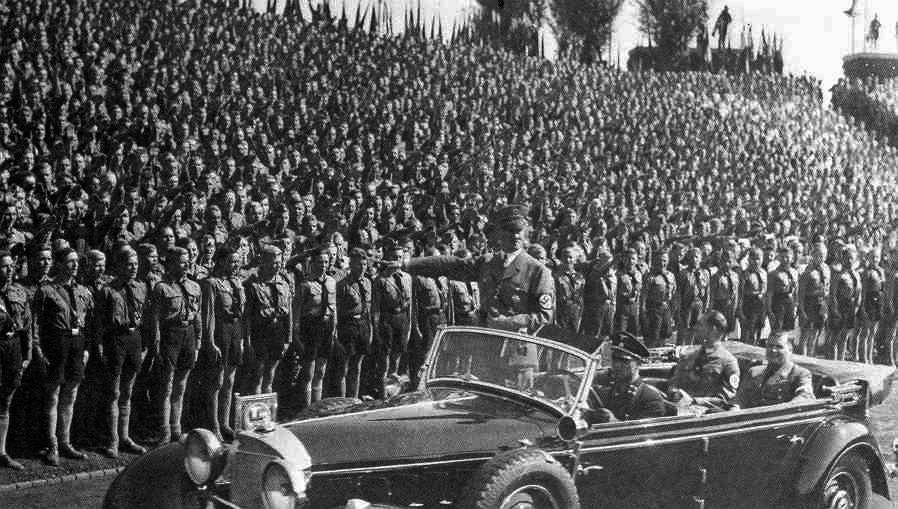

Hitler's "New Order" (Neuordnung)

Hitler's "New Order" (Neuordnung) Italy's Mussolini

Italy's Mussolini France and England seem to have little will to oppose the dictators

France and England seem to have little will to oppose the dictators The Spanish Civil

War

(1936-1939)

The Spanish Civil

War

(1936-1939) Japanese

imperialism in

Asia

Japanese

imperialism in

Asia The expansion of Hitler's Nazi empire goes unchallenged

The expansion of Hitler's Nazi empire goes unchallenged Nazi assault on the Jews intensifies

Nazi assault on the Jews intensifies America retreats into a deep spirit of

isolationism

America retreats into a deep spirit of

isolationism

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges