Born in 1884, Truman had been raised on a 600-acre

farm in Missouri to a father who was active in local Democratic Party

politics and a mother who encouraged in him an early interest in music

(the piano) and reading (though he did not undertake formal schooling

until he was eight). After graduating from high school in 1901 he

briefly (one year) attended a business school in Kansas City and then

took a series of jobs as a clerk, before returning to the family farm.

He had wanted to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but

had been rejected because of his poor eyesight. Thus he joined the

Missouri National Guard in 1905, attaining the rank of corporal in an

artillery battery (he was able to enter the National Guard by first

memorizing the eye chart!).

He dropped out of the National Guard in

1911, but rejoined the unit when America entered World War One in 1917

– helping to sign up other young men to his unit. Popular with the men,

they elected him as their 1st lieutenant. At training camp, he worked

with both Edward Jacobson, who would become a business partner after

the war, and Tom Pendergast, son of Kansas City Democratic Party

political boss Pendergast – a connection that would eventually bring

Truman into the world of politics.

In France Truman was promoted to captain,

and given command of an unruly artillery battery, which he disciplined

– to the strong opposition of the men, at first. He ultimately proved

to be an excellent leader, and also an independent thinker, who

disobeyed orders and had his men destroy a German artillery battery –

thereby saving an American division that would have come under the

heavy fire of the German battery. His discipline and leadership

resulted in the loss of not a single man in his unit, and their eternal

love and support of Truman (which would later factor into his political

rise from obscurity). After the war Truman would continue to serve in

the Reserves, rising to major (1920), lieutenant colonel (1925) and

colonel (1932).

Also after the war, Truman joined up with

Edward Jacobson to open up a men’s clothing store (haberdashery) in

Kansas City, giving Truman enough financial leverage to finally marry

Bess Wallace. But the store failed in the post-war recession of 1921.2

However his relationship with Tom Pendergast led Truman to be supported

in his run for office as a county judge (actually more like a county

commissioner, as it was an administrative rather than a judicial job).

In 1923 he took up the study of law (night school) hoping to eventually

become a lawyer. But even Pendergast’s Democratic Party support could

not prevent Truman from losing his office in the 1924 Republican Party

electoral sweep across the nation, and he took up another clerical job

and dropped his law studies (1925). Then in 1926 he was returned to

office (again with Pendergast support) as the county’s presiding judge,

but did not resume law studies. He would be re-elected to the office in

1930.

At this point Truman’s hard work and

self-discipline registered itself in the modernization of Kansas City

(numerous public works projects), in which Truman played a key role.

Then with the onset of the Great Depression, Kansas City Boss Tom

Pendergast (Pendergast’s father, who was personally very impressed with

Truman’s strong performance) had Truman appointed by Roosevelt as

Missouri director of one of the president’s New Deal programs,

initiating a personal connection between Truman and Roosevelt’s special

advisor, Harry Hopkins.

After much back and forth maneuvering,

Pendergast finally decided to support Truman as the Democratic Party

candidate in the 1934 race for U.S. Senate. With the nation's

continuing blame of the Republican Party for the Great Depression,

Truman scored a huge margin of victory over his Republican rival and

entered the U.S. Senate in 1935, with the accompanying label as "the

senator from Pendergast." Living down the reputation as being nothing

more than the tool of a notorious urban boss would not be an easy

challenge to rise above. But Truman would eventually prove himself to

be a man of unshakeable integrity. At the same time, he would also be a

through-and-through New Deal Democrat, voicing the standard litany

against Wall Street and the greedy corporate world. However, being a

freshman senator, it would be a long while before Roosevelt would take

any particular note of him.

In 1940, Truman was on his own in facing

reelection (Boss Pendergast had been imprisoned for income tax

evasion), being opposed in the Democratic Primary by Missouri's former

governor and by a well-known U.S. Attorney. But the two opponents split

the vote of the group opposing Truman and Truman received the

Democratic Party nomination, and a narrow victory over his Republican

opponent in the November 1940 elections.

Meanwhile, Truman's hostility to corporate waste had him in late

1940 create and chair a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Military

Affairs investigating U.S. army bases. Then with America's entry into

World War Two a year later, the work of his Truman Committee would soon

draw national notice. His committee not only eventually saved the U.S.

government from as much as $15 billion in waste but also drew the

attention of Time Magazine which featured him on its March 1943 cover

(the first of many).

Thus it was that Truman's name came up

when in 1944 Roosevelt began considering his run for a fourth term as

U.S. president. Henry Wallace had been serving as Roosevelt's vice

president. But Wallace's virtually Socialist ideals were putting off

Democratic Party leaders. Close involvement with Russia was raising

many questions about how America wanted to shape its post-war economy.

Socialism was coming to be identified with government tyranny, on the

Stalinist model. Meanwhile capitalism had cleared itself with its

enormous output of industrial goods during the war. Thus the country

was swinging against the Socialist tendencies of New Deal programming

and more to the hope of a post-war capitalist revival (though certainly

not an idea that would go unchallenged). Wallace was thus increasingly

problematic as vice president. And so it was that Roosevelt and his

advisors turned to Truman as a compromise candidate. And with the

Democratic Party's 432–99 win over the Republican Party in the 1944

election, Truman became America's vice president. And thus it was also

that Truman soon became the new U.S. president.

Personally, Truman was himself shocked

that, with Roosevelt's death only a few months into the new

presidential term, such a heavy post-Rooseveltian legacy had suddenly

fallen on his shoulders. He was fully aware of the heavy

responsibilities of the presidential office, especially during this

time of war, and was unsure of the level of support he would receive in

having to fulfill those responsibilities. But he was one who had

learned to accomplish much, especially when so little was expected of

him.

In that same month that the presidency

fell on his shoulders Truman went before Congress and prayed a prayer

that certainly also the nation was praying at that time:

As I have assumed my heavy duties, I humbly pray Almighty God, in the words

of King Solomon: "Give therefore thy servant an understanding heart to

judge thy people, that I may discern between good and bad; for who is

able to judge this thy so great a people?" I ask only to be a good and

faithful servant of my Lord and my people.

Indeed, Truman would attempt to live up to that enormous

responsibility. But actually, few thought at the time that this new and

unsought president would be able to meet those standards. In fact

Truman would have a hard time winning the hearts of the American

people, who had become used to the rather majestic presence of

Roosevelt at the helm. Getting the Americans to see in Truman little

more than the qualities of a next-door neighbor or somebody's uncle

would take longer than the time he was actually in office. It would

really not be until a generation later that Americans could look back

and see that Truman at the helm – rather than Roosevelt, at a time when

hard-nosed common sense and not just presidential majesty was required

in the mounting conflict with Soviet Russia – was itself an act of the

same Almighty God that Truman had appealed to in that prayer.

Despite his common ways (often even

profane in language) Truman personally was a man of great personal

faith in God and Christ, a man of daily prayer, and highly Biblical in

the way he analyzed, categorized and chose critical decisions that fell

to him to make. Most of this was of a very private nature, but highly

important to the nation that he would have to guide through the

political, economic, social and spiritual minefields that awaited

America and the world after the collapse of the German and Japanese

empires.

Preparing for a post-war world

Preparing for a post-war world Roosevelt suddenly dies (April 12, 1945)

Roosevelt suddenly dies (April 12, 1945) The

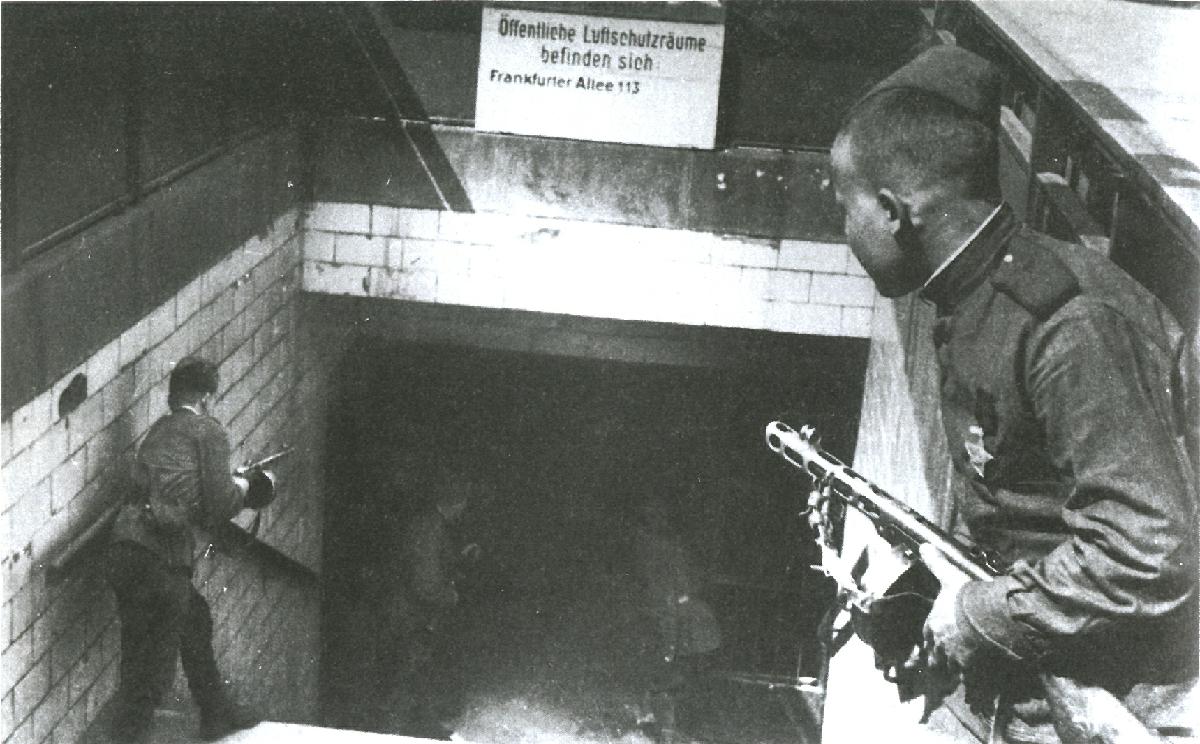

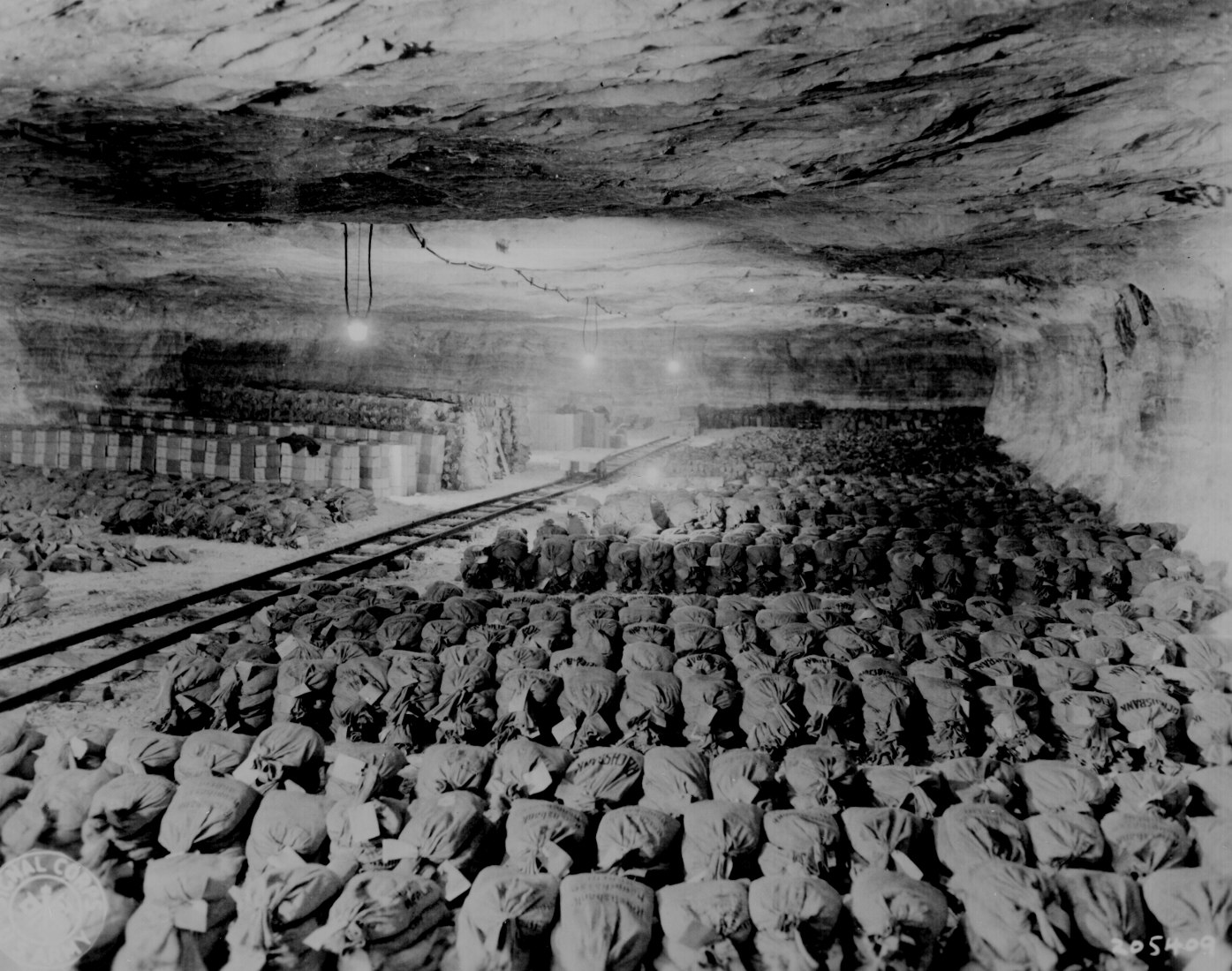

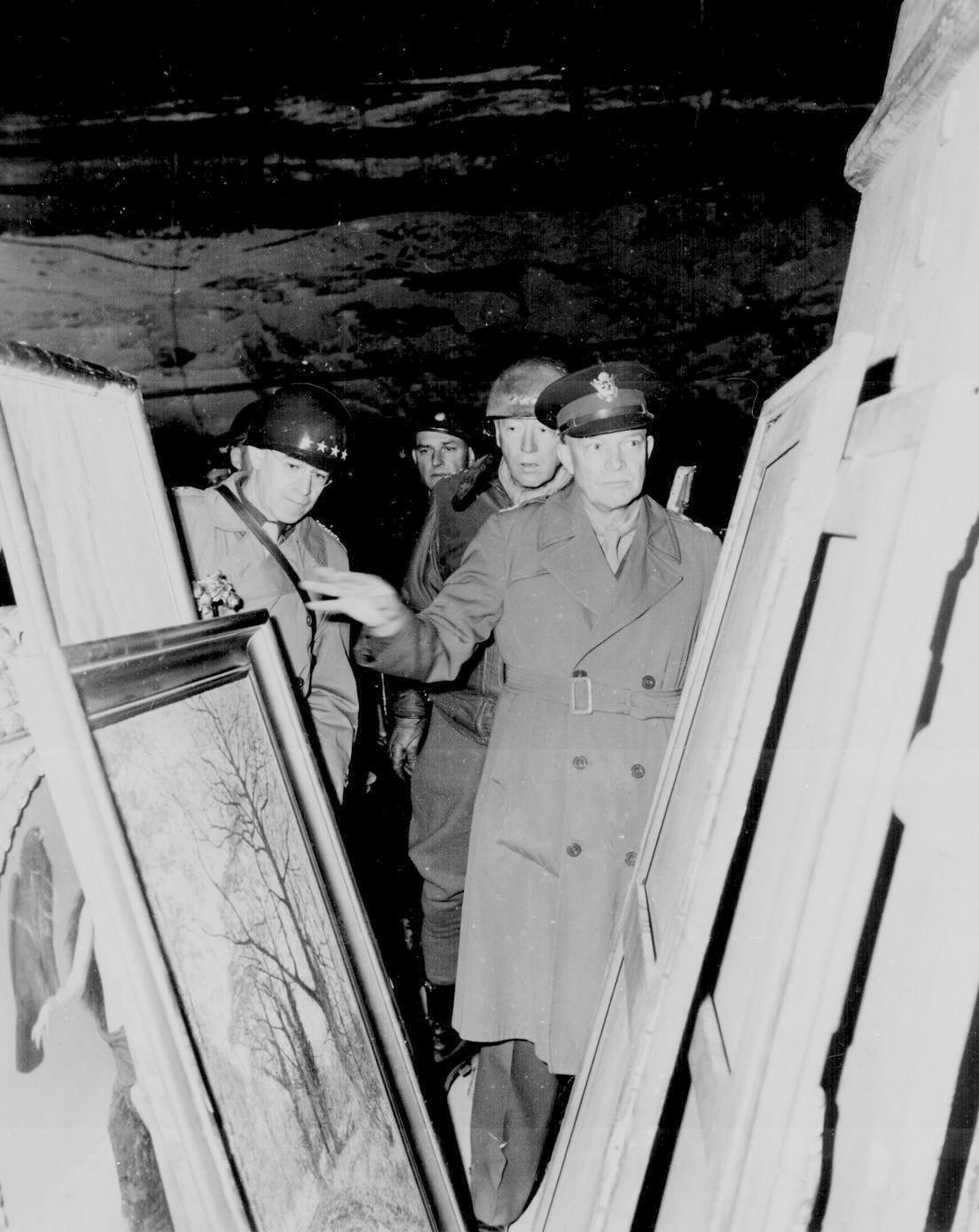

final destruction of Hitler's German Reich – April-May 1945

The

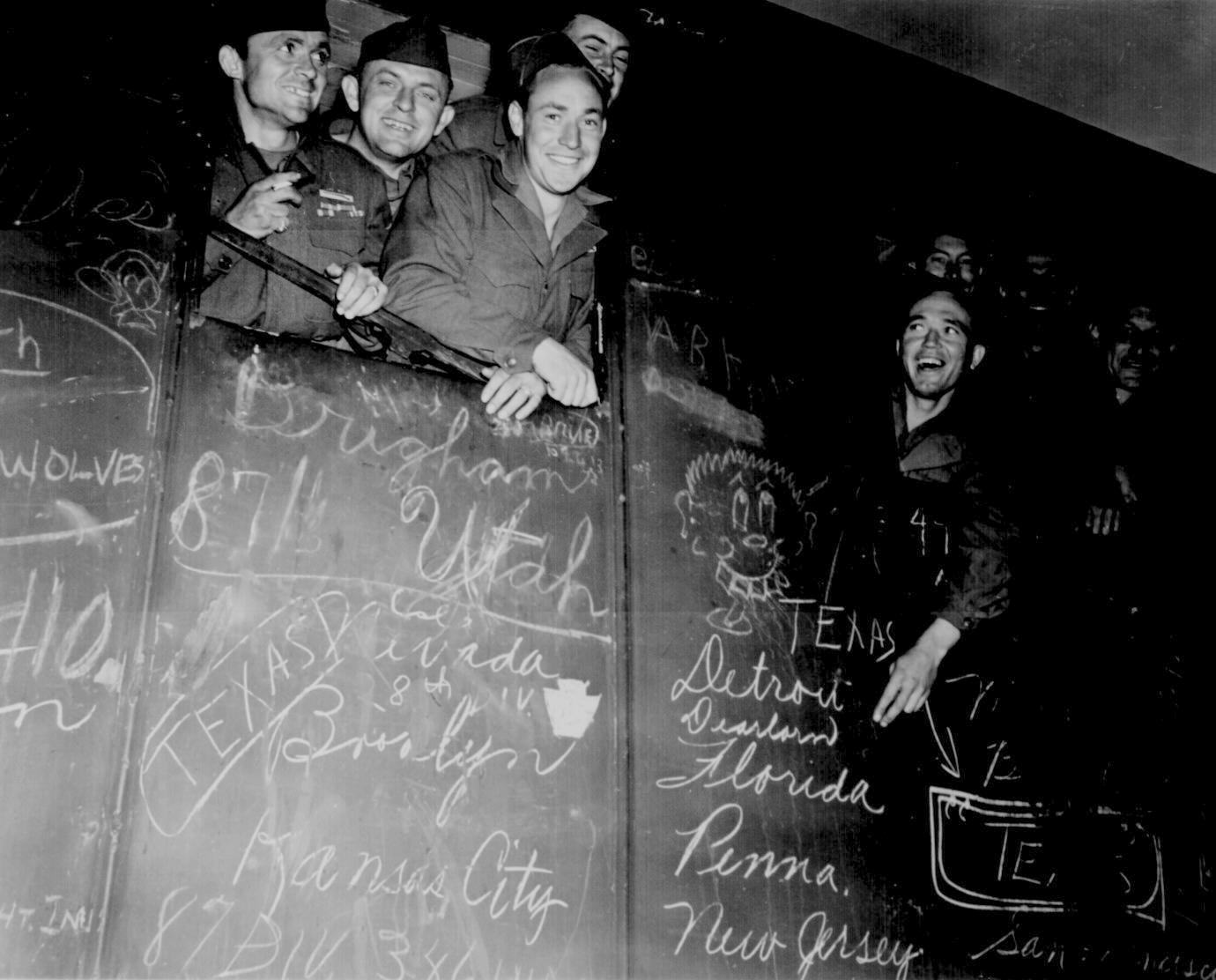

final destruction of Hitler's German Reich – April-May 1945 The war in Europe is finally over

The war in Europe is finally over Political considerations thrust themselves

forward

Political considerations thrust themselves

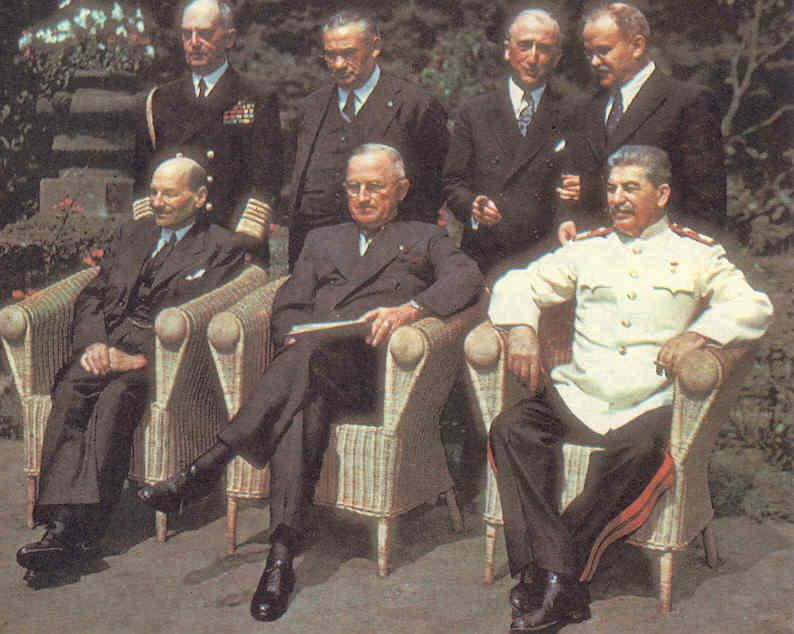

forward The Potsdam Conference – July 1945

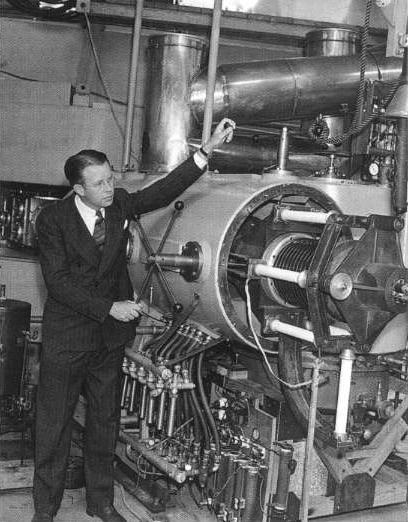

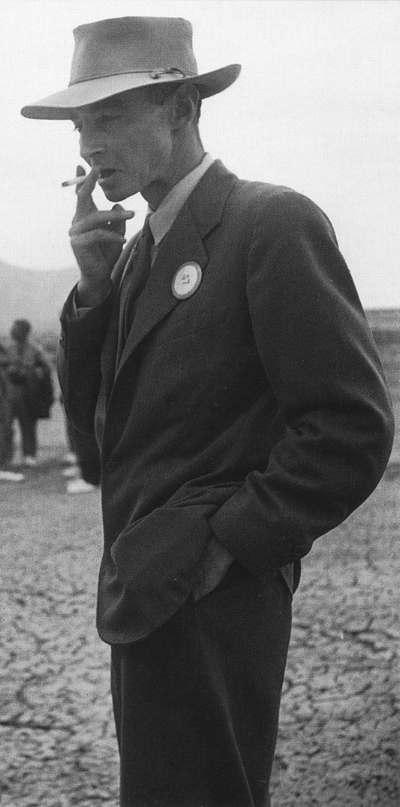

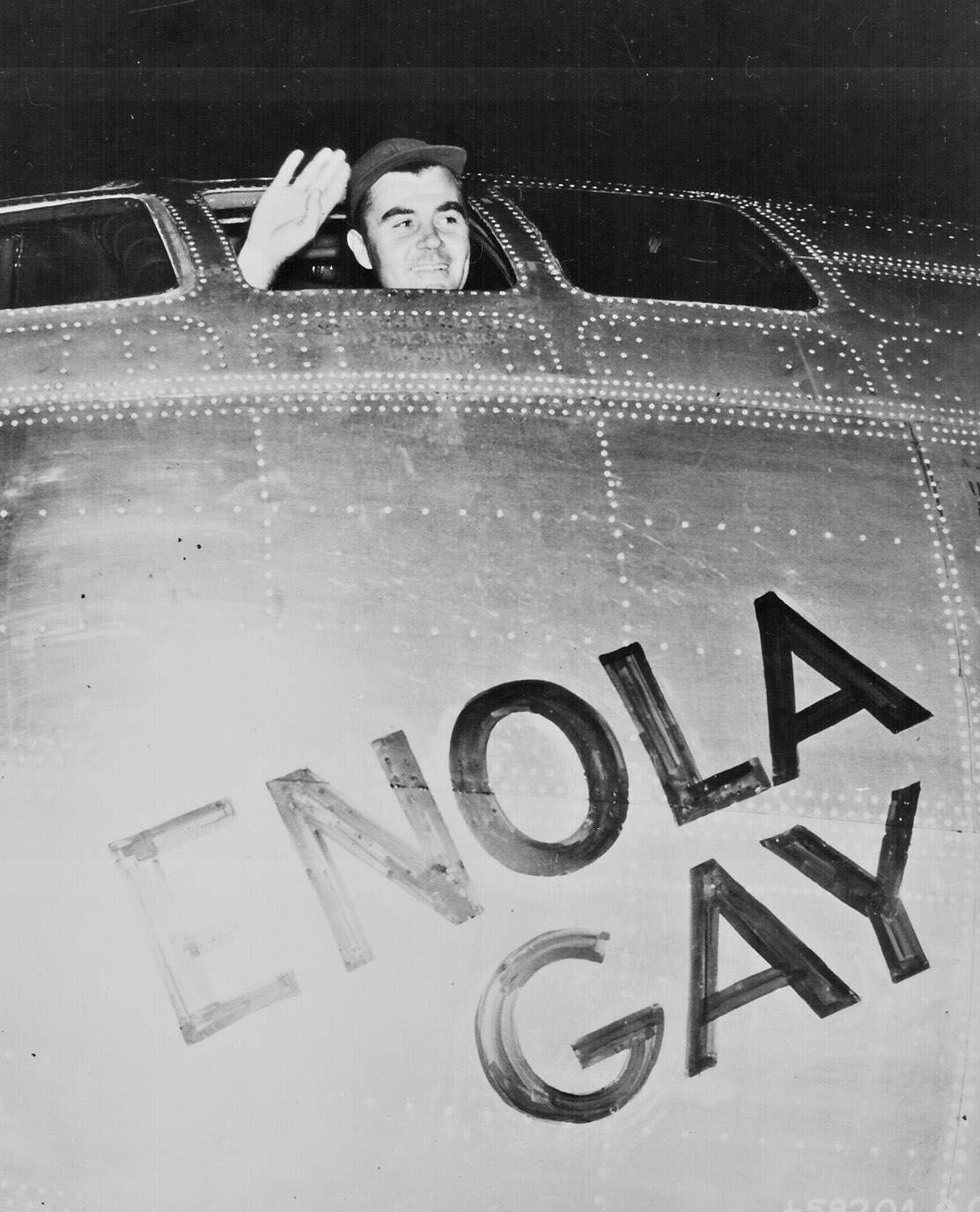

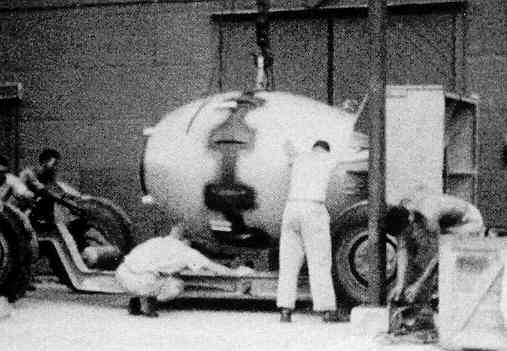

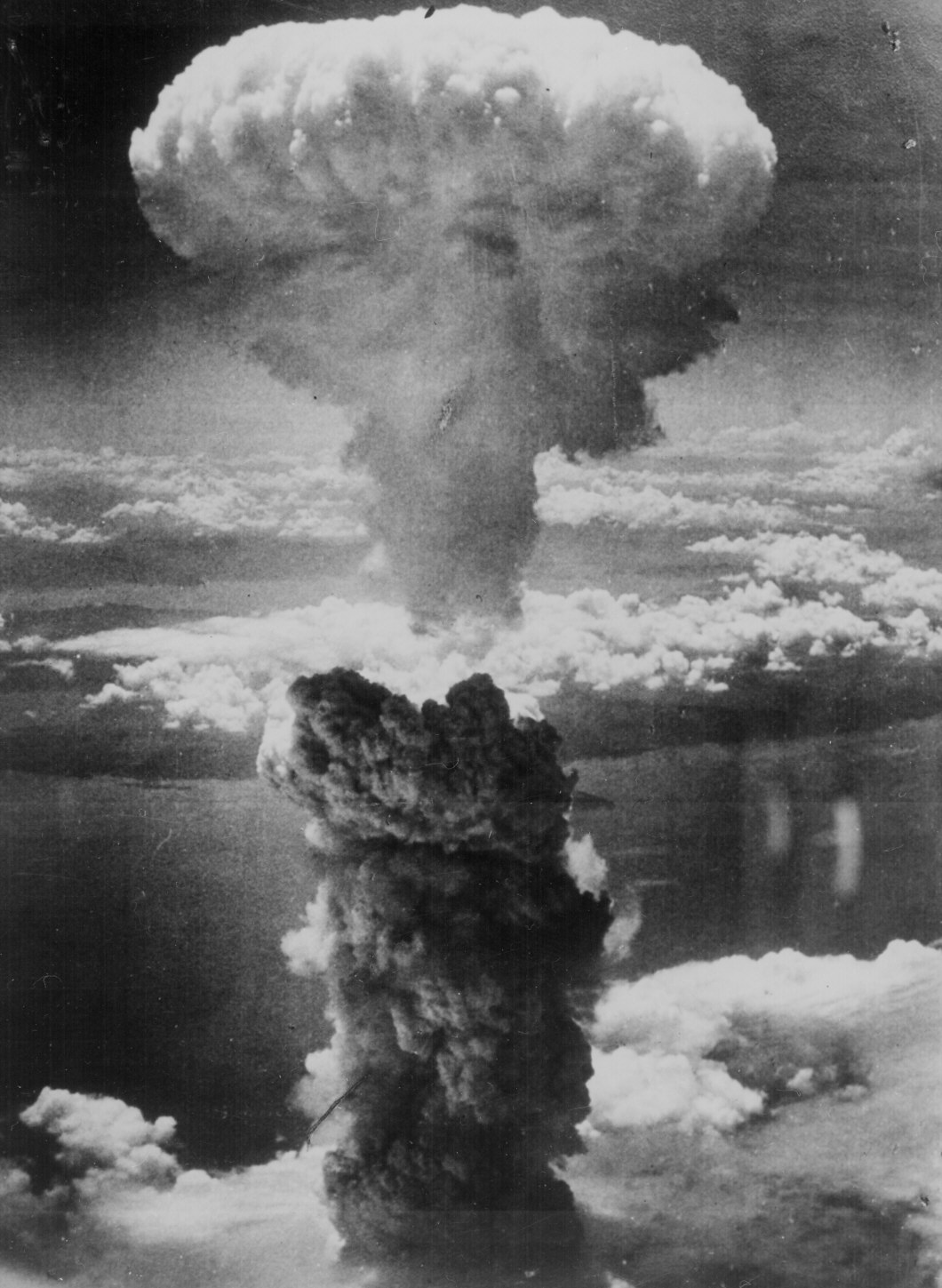

The Potsdam Conference – July 1945 The atomic bomb

The atomic bomb Peace at last!

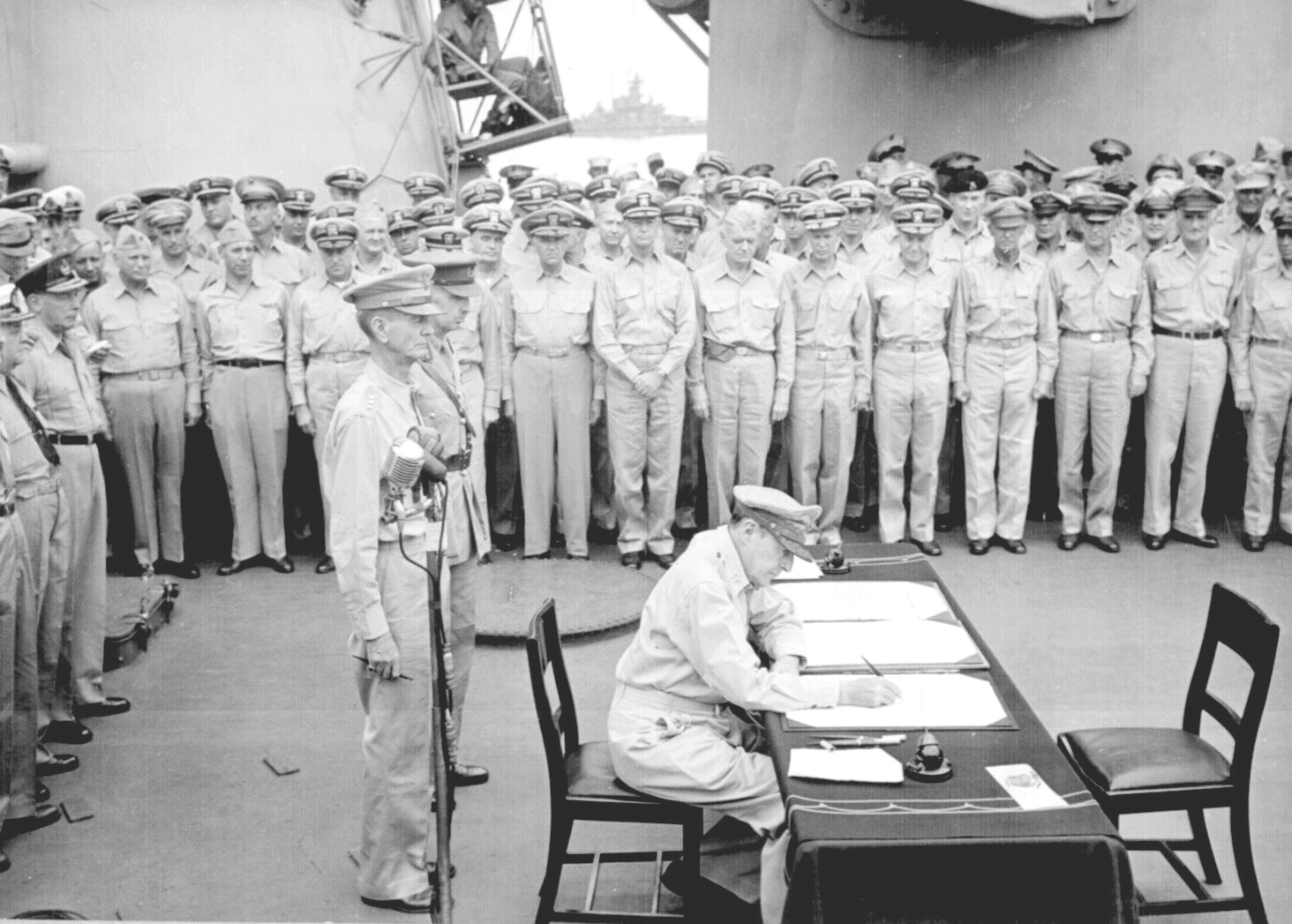

Peace at last! Japan's formal surrender -

September 2, 1945

Japan's formal surrender -

September 2, 1945