Westerners were shocked by the Communist takeover

in formerly free Czechoslovakia ... including finally the

Americans. Truman of course was not. Nor did he come to the same

sense of alarm as did the newly awakened Americans. In America

the Czechoslovakian crisis succeeded in reviving an old Red Scare, one

that would shape nearly all understandings of America's role in the

world for the next generation.

Truman saw things a bit differently. He

certainly understood the challenge that Marxist ideology posed to the

values of Western democracy. But he was more interested in how this

challenge directed political behavior of specific societies, in

particular Stalin's Russia. Truman was more interested in power

politics than in grand ideology. He was thus able to carry off a highly

advantageous diplomatic move, one that within a couple of years would

have been impossible, given the rising ideological mood of America.

This diplomatic move concerned Tito's Yugoslavia.

During World War Two Josip Broz Tito had

headed up a huge military unit of Communist Partisans that gave the

Germans a massive amount of trouble in Yugoslavia. In early 1945, as a

full German defeat looked increasingly likely, Tito took charge of a

new provisional government debating the question of forming a new

republic or continuing the monarchy under the young King Peter II. In

elections held in November of 1945, the pro-monarchists largely

boycotted the event, delivering a huge victory to Tito's

pro-Republicanists – dominated heavily by the Communists, who had

achieved a very high moral standing among Yugoslavia's various ethnic

groups because of their dedication to ousting the Germans from the land.

Though Tito was a loyal Stalinist, he was

also an independent thinker, and had specific plans of his own for

Yugoslavia. Those plans included incorporating all of the Trieste

territory to the northwest of the country (including shooting down

American planes supplying Trieste with aid) plus building his own

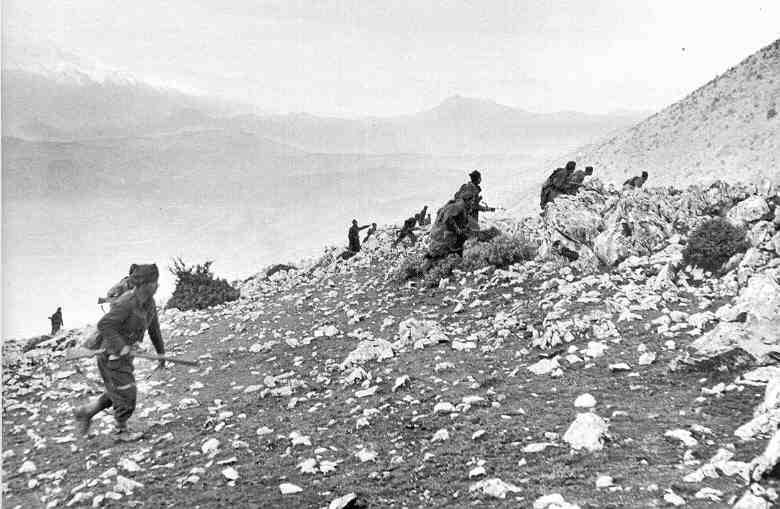

diplomatic alliance with the Greek Communists to the south. This upset

Stalin greatly because he was afraid that Tito's activities would call

forward a strong American response (which it did), Stalin having come

to appreciate the strengths of the new American leader, Truman.

Tito also had his own ideas of how he wanted to unite economically the ethnically divided Yugoslavia.

Such independent-mindedness annoyed

Stalin greatly, as he wanted all Communist organizations to function

under his sole authority. Problems between Tito and Stalin thus began

to develop.

Ultimately, Tito refused to attend the

second meeting of Stalin's new Cominform held in June of 1948,

expecting to be verbally attacked by Stalin. Stalin was furious at this

affront and called for Tito's expulsion from the Cominform, Stalin

expecting his personal disapproval to be the undoing of the

independent-minded Tito. When expulsion did not seem to have the

desired effect, Stalin took up his more usual program of seeking to

eliminate any who dared to oppose, or even question, him. None of

Stalin's efforts succeeded however. Tito in turn now went after any

supposed Stalinists in his own country, arresting thousands.

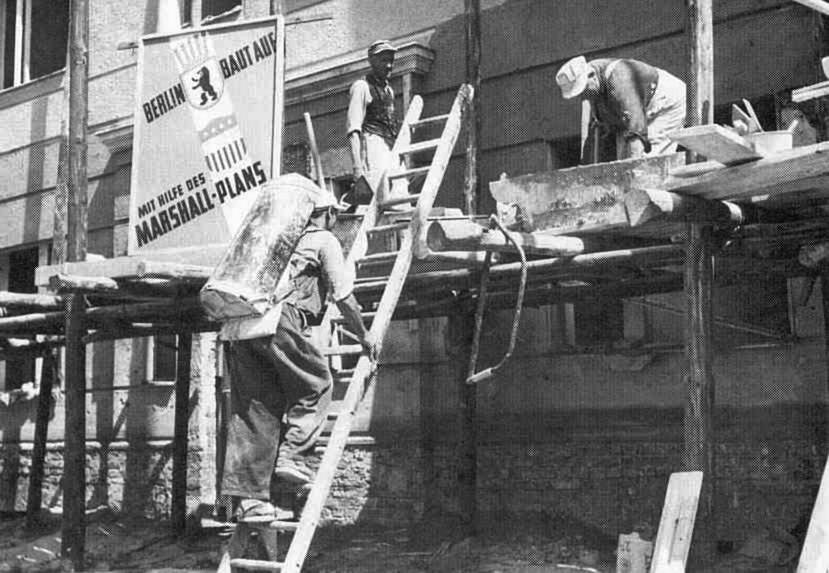

This turn of events opened the way for

Tito to access America's Marshall Plan (1951). Receiving American

financial (and also some military) support did not exactly align Tito

with the growing Western diplomatic alliance headed up by America. But

it effectively made Yugoslavia an openly neutral or non-aligned country

in the Cold War. Indeed, Tito went on to be one of the key leaders of

an international movement – at the time principally among Asian states

– which declared itself to be aligned with neither the West nor the

East. These non-aligned countries saw themselves as comprising a new

"Third World."

Truman was not looking for Yugoslav

loyalty in his swing of economic support behind his former adversary.

What Truman did achieve through this support of Communist Yugoslavia

was keeping Stalin from acquiring Yugoslavia as another satellite

state, one particularly that might have given Stalin the opportunity to

extend his political reach all the way to the Adriatic Sea just

opposite Italy and thus also a position on the Mediterranean Sea, a

goal long sought by the Russians. In supporting the Communist Tito,

Truman had contained Stalin. That loomed in importance much larger in

Truman's mind than the idea of opposing Communism, no matter where it

showed its head, for such ideological crusading would have helped drive

Tito back into Soviet hands, the very thing sought by Stalin.

This was cool-headed thinking on the part

of Truman, something unfortunately that would be lost on the vast

majority of Americans – who at this point were beginning to see things

in absolute Black-White (or Red-White!) dimensions.

Truman takes on early global challenges

Truman takes on early global challenges The mounting sense of a Soviet or Stalinist danger

The mounting sense of a Soviet or Stalinist danger Crisis in Greece and Turkey ... and the "Truman Doctrine"

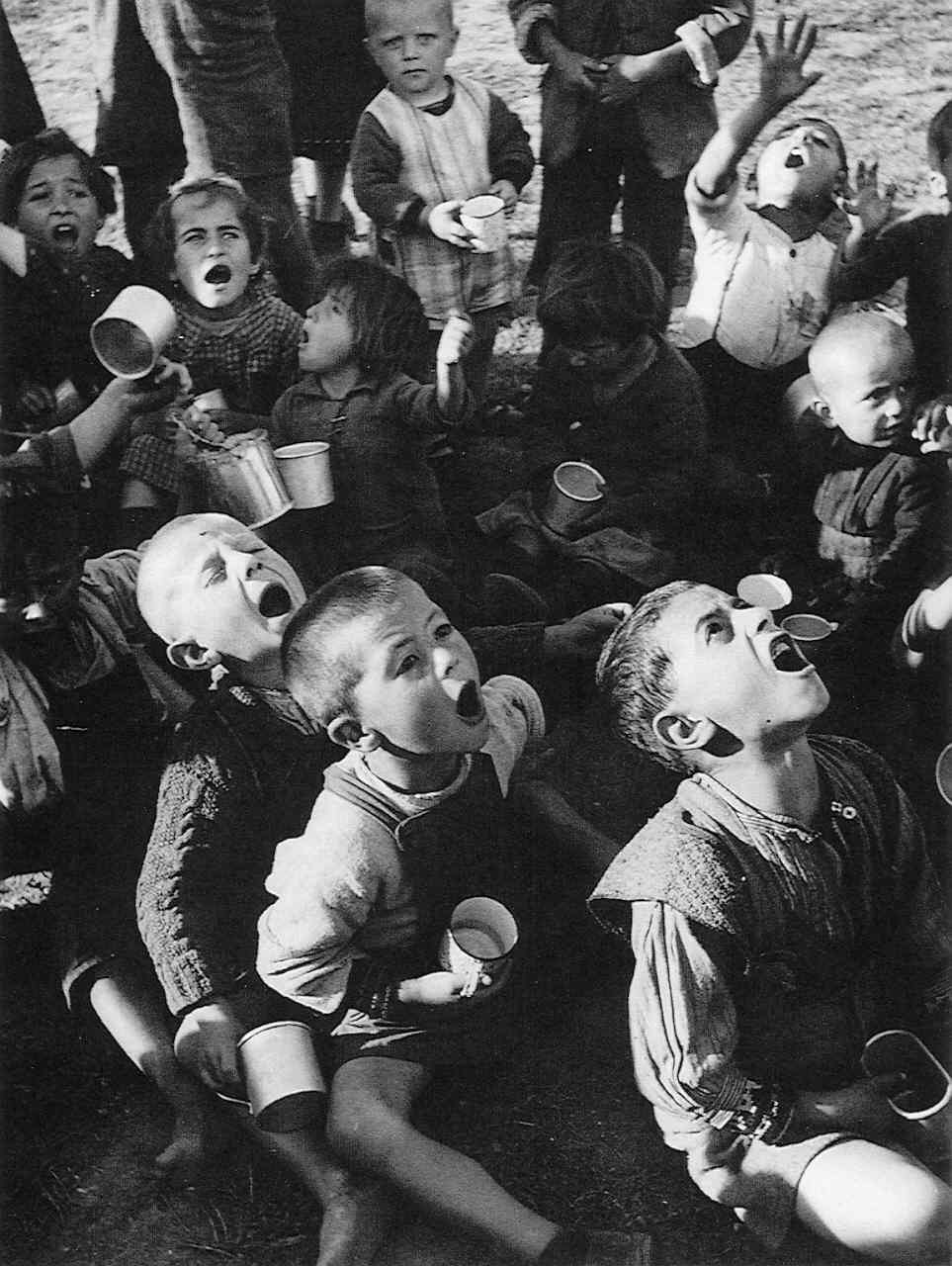

Crisis in Greece and Turkey ... and the "Truman Doctrine" Mounting problems in Western Europe ... and the Marshall Plan

Mounting problems in Western Europe ... and the Marshall Plan The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia

The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia  Helping Tito move out from under Stalin's control

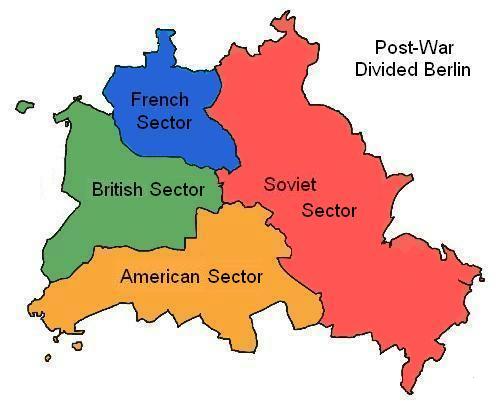

Helping Tito move out from under Stalin's control The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May 1949)

The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May 1949) The ineffectiveness of the UN ... and the Creation of NATO

The ineffectiveness of the UN ... and the Creation of NATO

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges