Wikipedia

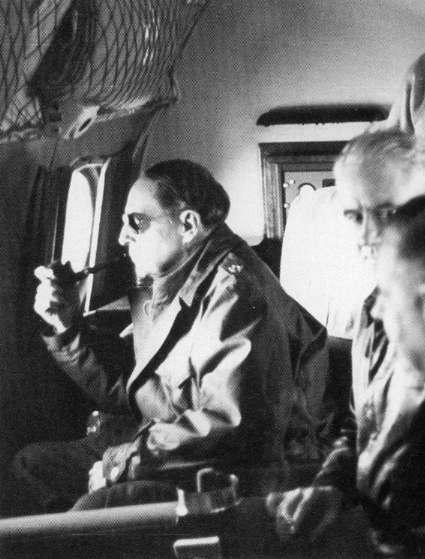

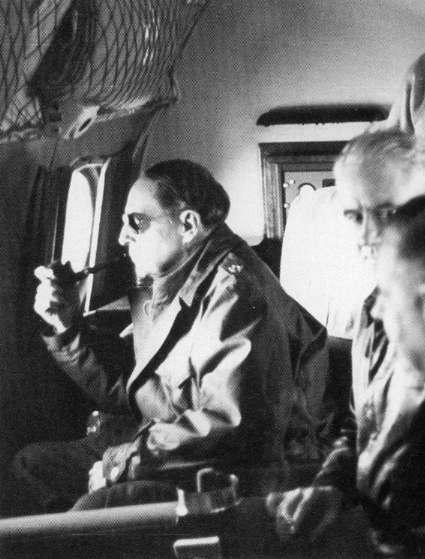

John Foster Dulles being

shown the 38th parallel in Korea – June 17. 1950

(just prior to the North

Korean invasion of the South)

John Foster Dulles Papers,

Public Policy Collections,

Department of Rare Books and Special Collections,

Princeton University Library

General Douglas MacArthur

– leading the UN forces in Korea

Library of

Congress

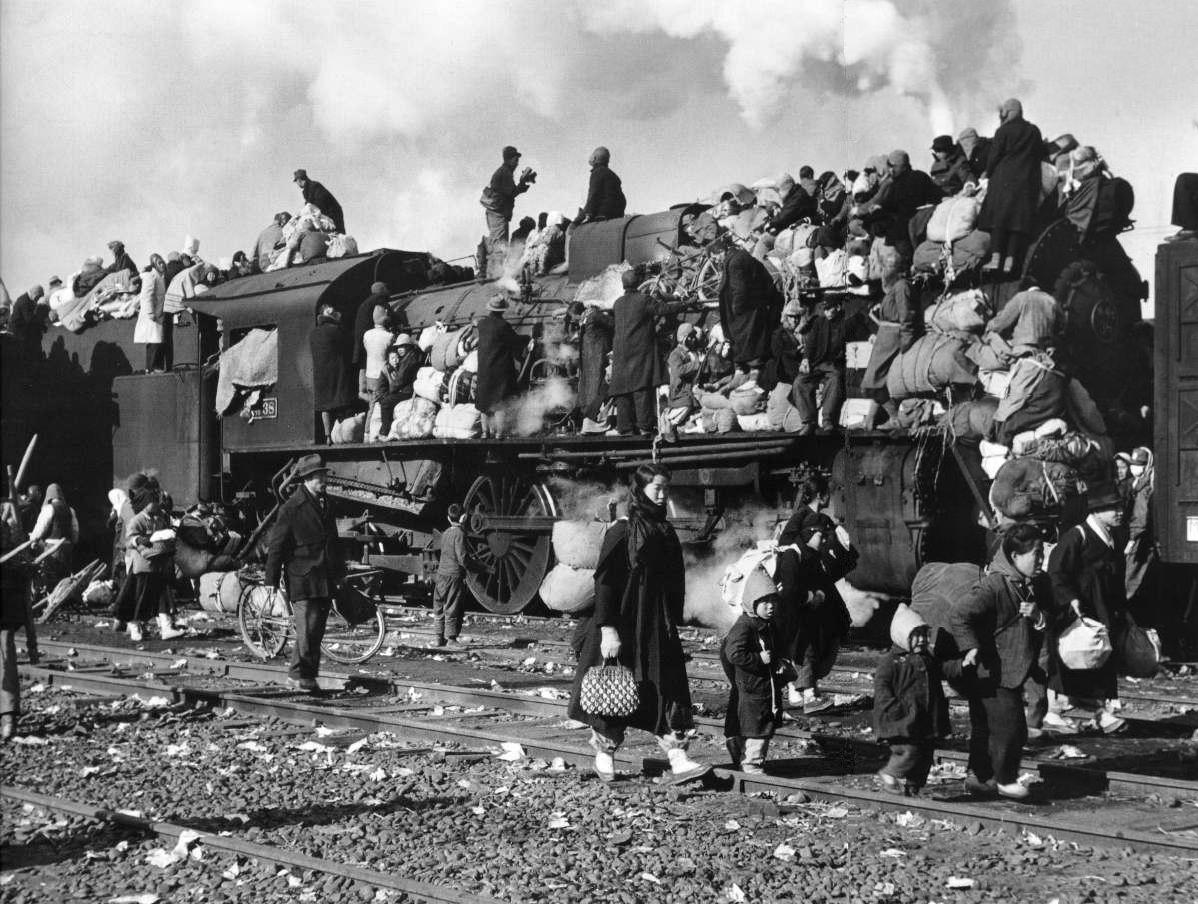

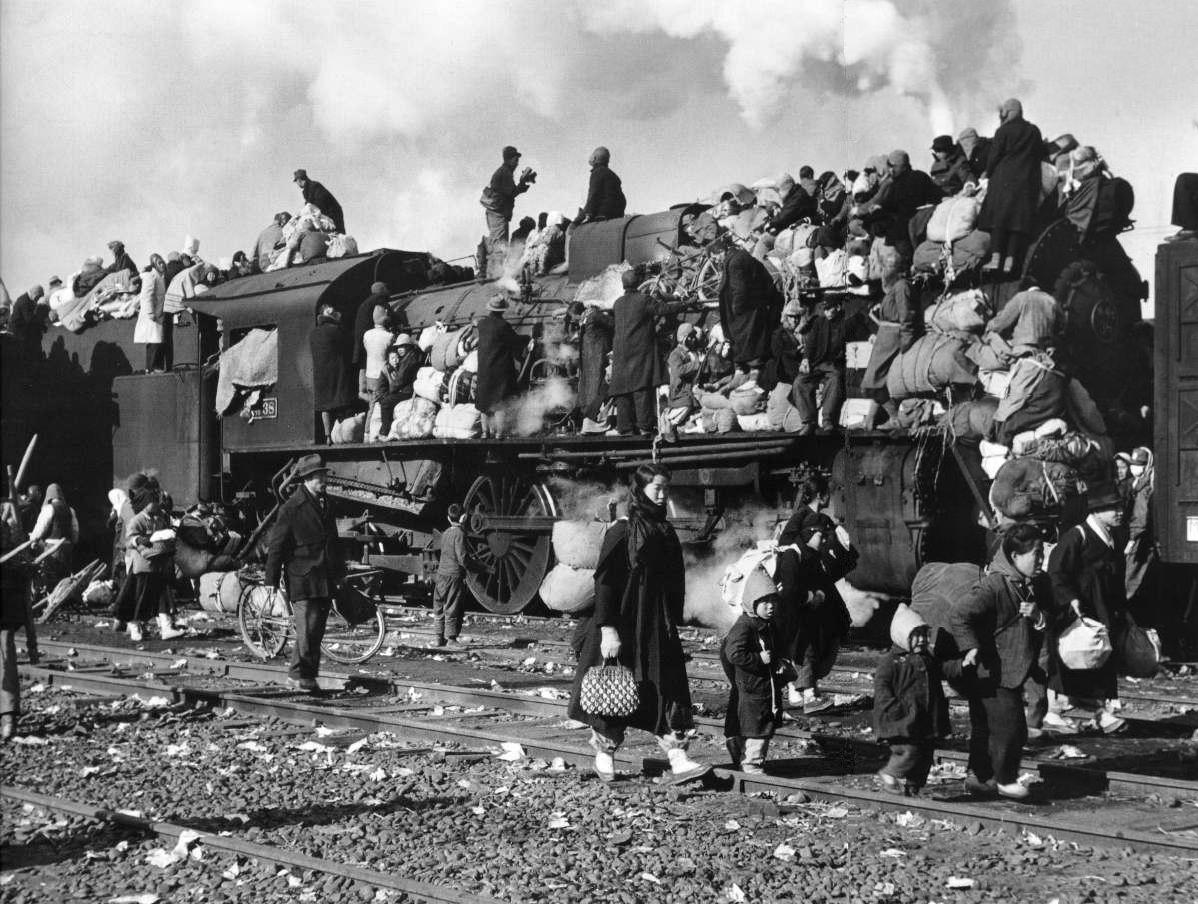

Koreans fleeing the

fighting

United Nations (US

Army)

Men of the 1st Cav Div go

ashore somewhere in Korea, 18 July 50.

United States Army

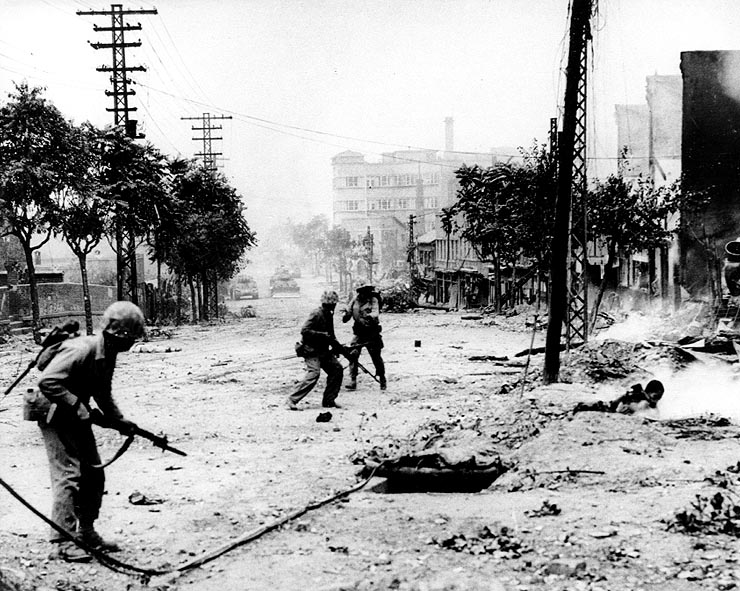

GI's advancing to the action;

Koreans civilians fleeing the action – August 1950

1st LT William Millward of

Baltimore, Md, Civil Assistance Officer, 5th Cavalry Regiment,

1st

Cavalry Division, distributes candy to Korean

children

at a refugee Collecting Point in Western Korea.

United States Army

Conferring at Chipyong-ni,

Korea, during General Ridgway's tour of the fighting front, are L-R:

LT GEN Matthew Ridgway,

CG US Eighth Army; MAJ GEN Charles Palmer, CG, 1st Cav Div;

COL John Daskalopoules,

CO, 7th Cav Regt, 1st Cav. Division

United States Army

Vehicles of the 1st Cavalry

Division move up to the front lines, somewhere in Korea, 3 Aug 1950

United States Army

|

THE LANDING AT INCHON (15 SEPTEMBER)

AND THE MOVE OF THE WAR TO THE NORTH

|

|

|

|

The landing at Inchon and the liberation of Seoul

It was decided to conduct an end run around the

North Koreans by sending an American landing party by sea somewhere to

the north behind the North Korean lines, cutting off their supply from

North Korea and trapping them in an encirclement. General MacArthur

understood well the lessons of Gallipoli (World War One) and Anzio

(World War Two), and was determined to move as quickly as possible off

their initial landing base on the beach ... actually, even quicker than

possible! Also the Americans made visible preparations for a landing

105 miles south of the intended landing point, in order to confuse

North Korean spies into believing that an American landing would take

place at Kunsan.

On 15 September 75,000 Marines were sent

ashore at high tide at Inchon. And then without hesitating they swung

directly behind lightly defended North Korean lines, catching the North

Koreans by complete surprise. Seizing a strategic airfield, the

Americans then began to fly in large numbers of soldiers and supplies.

U.N. troops then headed for Seoul, engaging in a fierce 11-day fight

for the ROK capital. By late September the city was cleared of the

enemy.

By this time North Korean troops were

retreating in huge numbers to the north, to protect their Communist

region from the attack from the south that they sensed would soon be

coming their way.

Crossing the 38th parallel

Mao's Chinese Communist government also

sensed the dangers headed its way and thus warned America not to move

north across the 38th parallel (the temporary line dividing North Korea

and South Korea) or China would be forced to intervene. But by October

1st, ROK troops had crossed the 38th parallel and a week later, with

U.N. authorization, so did a large number of UN (largely American)

troops.

Less than two weeks later the U.N. troops had captured the North Korean

capital at Pyongyang, and then they pushed north, attempting to capture

escaping North Korean leaders. In the process they took 135,000 North

Korean soldiers captive. At this point (the end of September) MacArthur

began speculating publicly about launching into China to capture bases

that had been supplying the North Korean army. But Truman did not want

to provoke the Chinese into a counter-move.

Thus Truman flew (October 15th) to Wake Island in the mid-Pacific to

meet MacArthur (whose arrogance led him to refuse to come to meet the

president in the continental United States) in an attempt to get some

kind of idea of what was happening. MacArthur assured Truman that the

Chinese would not dare to intervene, for "there would be the greatest

slaughter" of the Chinese because they would be lacking adequate air

cover.

|

Soldiers Climbing Sea Wall

in Inchon – September 15, 1950

The Battle of Inchon (code

name: Operation Chromite)

was a decisive invasion and battle during the

Korean War.

Paratroopers of the 187th

A/B BCT float earthward near Munsan, Korea.

United States Army

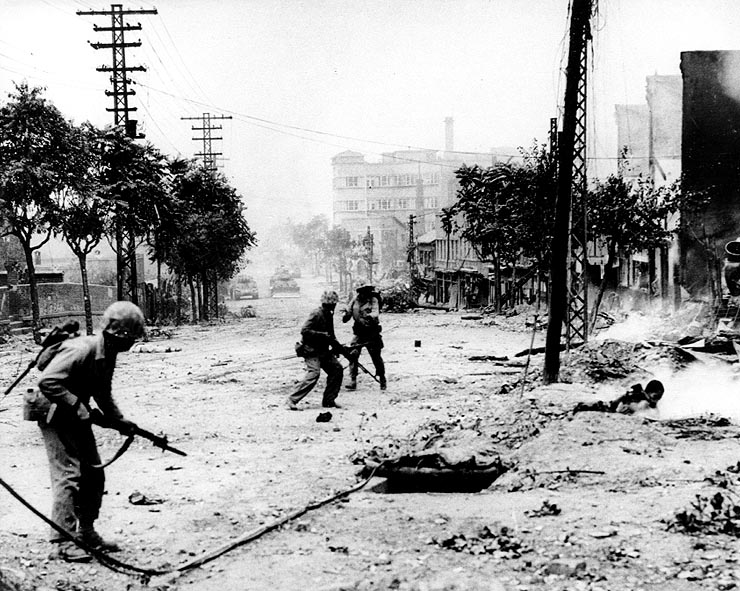

U.S. Marines fighting in

Seoul, Korea, Sept. 1950

Troops manning 90mm guns,

supporting the 5th Regimental Combat Team, 1st Cav Division,

on the Taegu

front lines, ready to lay down a barrage

on the Communist led North Korean as

UN Forces attack.

United States Army

U.N. artillery in

Korea.

U.S. Department of

Defense

Equipment captured from the

North Koreans is examined by men of the 5th Cavalry Regiment,

Waegwan,

Korea.

United States Army

Gun crew of a 105mm howitzer

in action along the 1st Cavalry Division sector

of the Korean battle front.

United States Army

Tanks and infantrymen of

the 1st Cav Division pursue Communist led North Korean Forces

approximately 14 miles north

of Kaesong, Korea.

United States Army

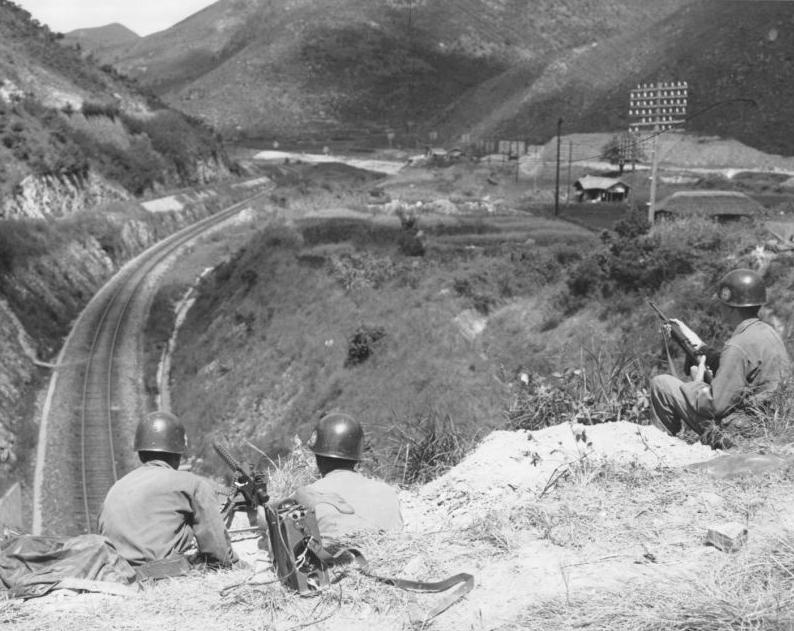

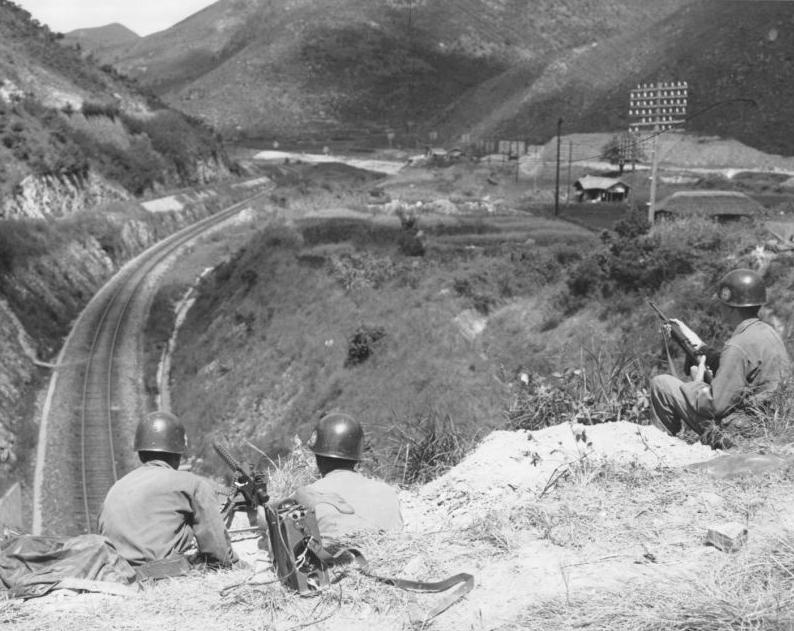

CPL George D. Smedley of

Mt. Vernon, Ind (L) and SGT Thomas P. Montana of Yuma, Ariz,

light machine

gun crewmembers

of Co C, 8th Cav

Regt, 1st Cav Div, watch for Communist-led

North Koreans troops on the

38th parallel line, northwest

of Kaesong.

United States Army

Personnel of the 378th Engineer

Combat Battalion, Eighth US Army, attached to the IX Corps,

install treadways during

the construction of a bridge.

United States Army

Yanks examine a Soviet-built

tank captured from the North Korean forces, Waegwan, Korea.

United States Army

Troops of Co. B, 519th Military

Police Battalion in position

above a railway tunnel with

a .30 caliber air-cooled machine gun.

United States Army

Men of the 5th Cavalry Regiment,

1st Cavalry Division, pass burning buildings and knocked-out

tanks of the North Koreans

as they advance to the front in Pyongyang.

United States Army

Cpl. Elmer Soprano, First

Platoon, Company A, 4th Signal Battalion. leans over a cliff to

fasten

a jumper, as they rehabilitate lines

from Tanyang to Chechon, Korea.

United States Army

Men of the 1st Cav Division

fighting in a train yard in Pyongyang, Korea.

United States Army

The company street of Co.

K, 31st Inf. Regt., 7th US Inf Div.

United States Army

U.S. forces target rail cars

south of Wonsan, North Korea, an east coast port city.

U.S. Army Military History

Institute

But this war – like any

other – is filled with tragedy

"A grief stricken American

infantryman whose buddy has been killed in action is

comforted by another soldier.

In the background a corpsman methodically fills out

casualty tags, Haktong-ni

area Korea."

By Sfc. Al Chang, August

28, 1950

National Archives

Men replace plain headboards

with crosses on graves in the 1st Cavalry Division

Temporary Cemetery, Taegu, Korea, 25 Aug

1950.

United States Army

Medical Co, 8th Cav Regt,

1st Cav Div-SGT E. O'Brien fills out tag to attached to a litter,

while Charles Sutton comforts

a wounded man who will be sent from this

medical aid station near

Yangzi, Korea, to a collection station further to the rear.

United States Army

|

CHINA INTERVENES

|

|

|

|

But Mao was indeed making plans for a massive

Chinese intervention. A buildup of Chinese troops along the border was

severely underestimated in size by MacArthur. Then on October 25th,

200,000 Chinese "volunteer"2 troops crossed the Yalu River into North

Korea, a group of them catching an American regiment by surprise and

nearly surrounding it, sending the Americans into retreat – although

the Chinese also withdrew immediately after the action. The Americans

were not sure what to make of the event.

The Americans resumed their northward

movement, this time running into a Chinese force of about 120,000

troops waiting for them at the Chosin Reservoir, which in the bitter

cold of a North Korean winter threw the 30,000 American troops back, in

a battle that lasted over two weeks – and which cost the Americans half

their troops as dead or wounded. Now the Americans found themselves in

retreat.

By mid-December the American Eighth Army

located in the Northwest had fallen all the way back to the 38th

parallel. This required American troops of the Tenth Corps in the

Northeast to have to fall back to prevent themselves also from being

outflanked, and to assist what was left of the Eighth Army. At this

time the Chinese removed North Korean dictator Kim Il-sung from

military command and took direct control of the armies fighting the

U.N. troops.

Then in early January (1951) the South

Korean capital Seoul was taken by the Communists for the second time.

But otherwise the line elsewhere between the enemy armies tended to

stabilize along something like the North-South line of division at the

38th parallel. Then in mid-February an Allied force of Koreans,

Americans and French managed to break a huge Communist troop offensive

and kill the further momentum of the Chinese. Now the Eighth Army went

on the counteroffensive against the Chinese army, which was running out

of supplies. U.N. troops thus recaptured Seoul and Kaesong and moved

once again across the 38th parallel.

The

Chinese attempted yet another huge attack (700,000 troops) on the UN

forces in late April, but after a month-long back and forth movement,

the line of battle remained pretty much the same as it had been before

the attack. Battles continued. A huge number of Chinese soldiers' lives

were lost (through malnutrition and disease as often as through

battle). But these battles had little effect on the overall picture. A

military stalemate had set in, one that would remain largely unchanged

despite periodic efforts to move it one way or the other.

2They

were classed as "volunteer" troops by the Chinese in the attempt to

avoid the appearance of a direct war being conducted by the Chinese

against the United Nations troops. But they were hardly "volunteers."

|

In late 1950 Chinese "volunteer" troops

(some 3000,000 of them) come charging

across the border into Korea – and suddenly it is an entirely

different game

The battle of the Changjin

or "Chosin" Reservoir – late November 1950

Wikipedia – "Korean

War"

MacArthur looking over North

Korea along the Yalu River border with China as the US

offensive reaches that

border – November 24, 1950. But somehow he failed to detect

the 300,000

Chinese

below gathering to counterattack the Americans.

National Archives

NA-111-SC-352944

GIs retreating before an

on-slaught of Chinese "volunteers" in North Korea

Marines retreating from the

Chosin Reservoir in sub-zero weather

Marine dead brought back

from the fighting in the Chosin Reservoir area

National Archives

NA-127-GK-197-A5348

American aircraft aboard

a snow-covered aircraft carrier – stymied by Soviet MiG-15

fighter jets

PFC William Stinnett Jr.,

Stevensport, Ky, maintains a vigil

against the Chinese Communists

at his post with the 5th Cavalry Regiment in Korea.

United States Army

Koreans fleeing the fighting

in 1951

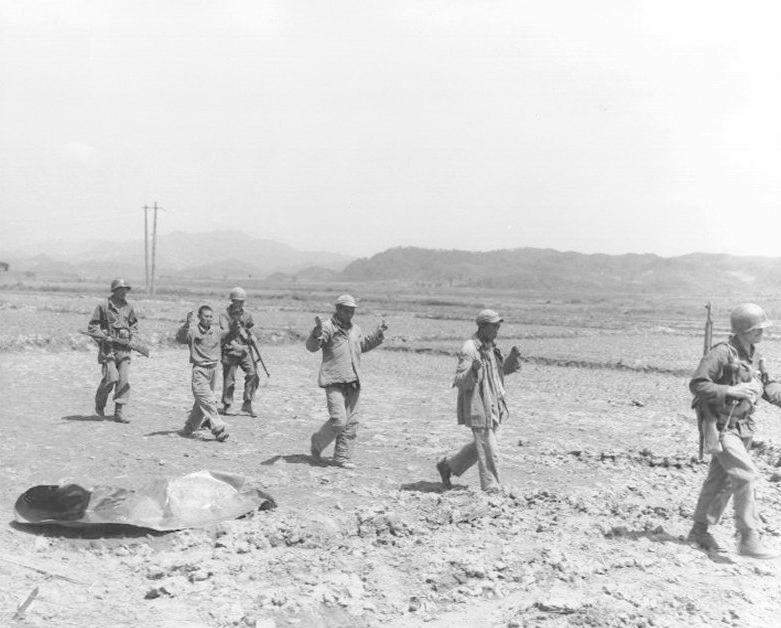

"Men of the 1st Marine Division

capture Chinese Communists during fighting on the

central Korean front.

Hoengsong."

By Pfc. C.T. Wehner, March

2, 1951

National Archives

Pinned down by Chinese

Communist

fire, men of the 15th RCT, 3rd Inf Div, take over

during the drive against the Communist forces

near the 38th parallel. 23 March 1951

United States Army

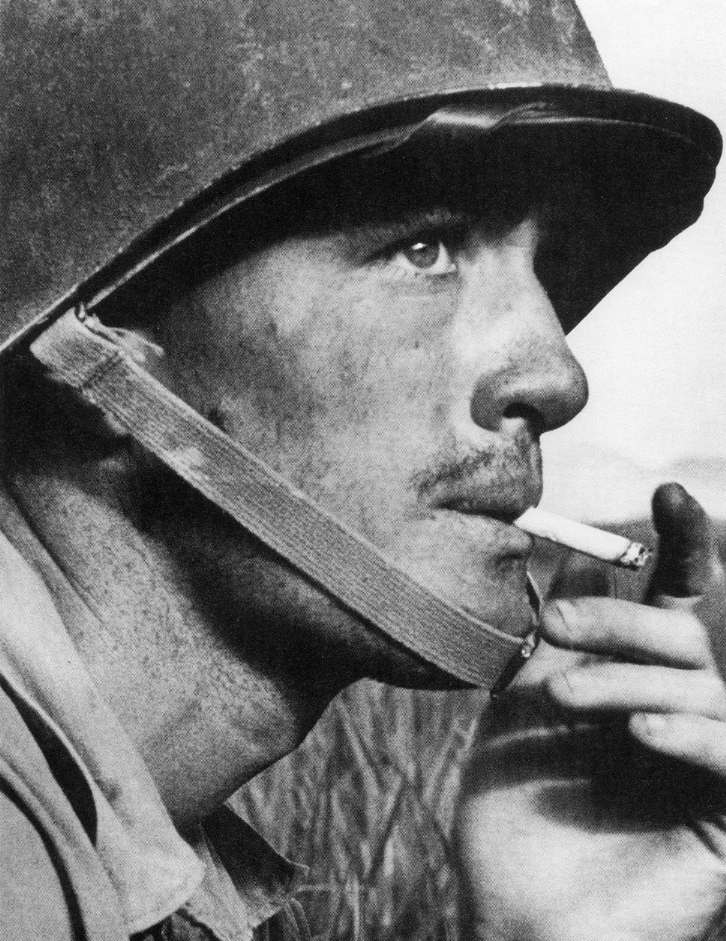

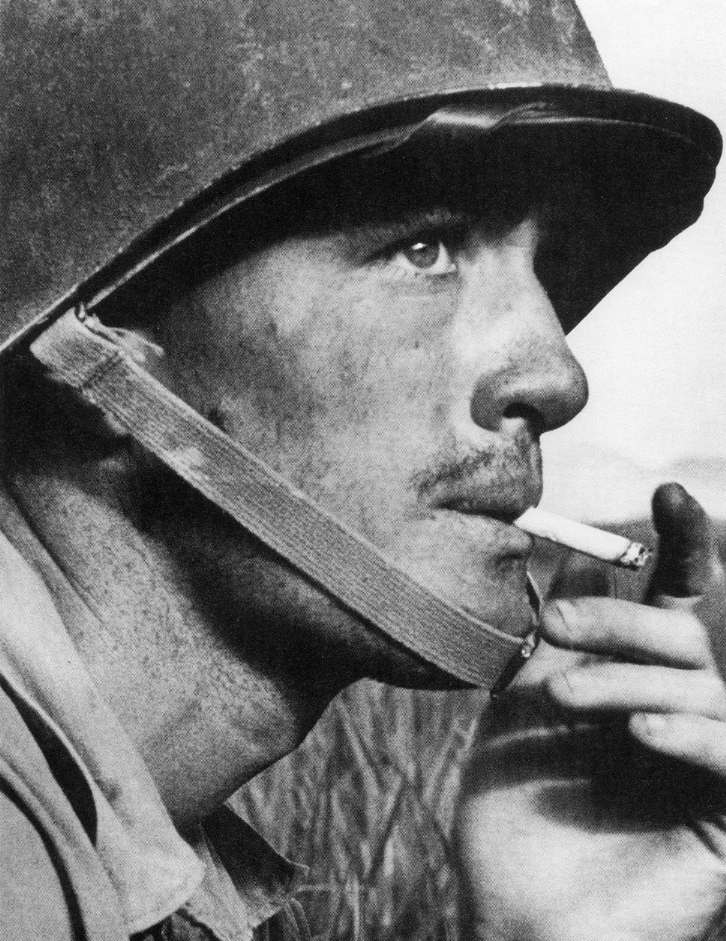

A wearied

Marine

GIs pinned down by enemy

fire near Anyang

|

MACARTHUR IS RELIEVED OF COMMAND

APRIL 1951

|

|

|

|

At this point (mid-April 1951) Truman relieved

MacArthur as Supreme Commander in Korea. Among other elements of

MacArthur's troubling behavior, MacArthur had come to feel that the

decision whether or not to use nuclear weapons in fighting the Chinese

should be his rather than the president's. In fact MacArthur seemed to

be boasting to the press about how he might actually do that, in order

to liberate all of China from the Communists. By now Truman was

furious. He was concerned not only about MacArthur dragging America

into a war involving the entire Chinese nation (which had not worked

out so well for the Japanese!) but he was also concerned about what

such a war would do to the American abilities to hold the line against

Russia in Europe (an issue of no apparent interest to MacArthur, who

was completely focused on the Asian theater of war). Thus it was that

Truman dismissed MacArthur – quite aware of the reaction this would

likely provoke among the American people. But it had to be done.3

3Because

of this action, many Americans came to view MacArthur as a national

hero – and Truman as a coward, if not almost a traitor. But a

Congressional investigation ultimately concluded that Truman had indeed

acted constitutionally, and correctly, and that MacArthur (who actually

spent all his time in Tokyo) was out of touch with the military

realities in Korea, as well as the critical challenges facing America

in the rest of the world.

|

MacArthur receiving a hero's

welcome in New York City (7 million turned out

to cheer him) after being relieved from

duty in Korea by Truman

|

THE WAR DRAGS ON

|

|

|

U.S. Troops advance on

Communist

forces in Korea – June 1951

Library of

Congress

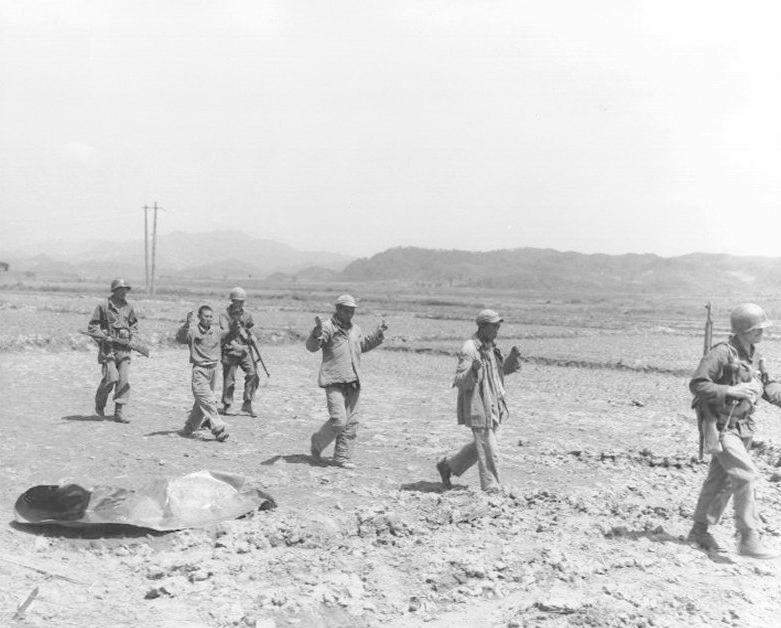

Men of the US 1st Cavalry

Division bring in Chinese Communist captives,

north of the Imjin River,

Korea, June 1951.

United States Army

American troops secure a

mountain top with mortar fire somewhere in Korea.

United States Army

Members of the 68th Battalion,

Division Artillery attached to the 1st ROK Div.,

fire their 90mm anti-aircraft

guns.

United States Army

Artillerymen of the 24th

Infantry Div fire 155mm howitzers at dusk, Korea.

United States Army

Koreans unload empty shell

casings from a truck at the 2nd Infantry Division Ordnance

Salvage Dump, where they will be salvaged

for reuse, 6 September 1951.

United States Army

M4A3E8 "Sherman" Tank of

Company B, 72nd Tank Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division,

fires its 76mm gun at enemy

bunkers on "Napalm Ridge", in support of the 8th ROK Division.

Photograph is dated 11 May

1952.

U.S. National Archives

Men and Pershing Tanks of

the 73rd Heavy Tank Battalion

await orders to board the

LST's at the Pusan Docks, Korea..

|

ARMISTICE

|

|

|

|

During the presidential campaign of 1952, Republican presidential candidate Eisenhower had made

the promise that if elected president he would personally go to Korea

to bring some kind of a resolution to the conflict that had been going

on since 1950, although most serious battlefield action had subsided

since mid-1952.

The sticking point to an agreement among the warring

countries was the question of repatriating Chinese and North Korean

soldiers who refused to return to their home countries, a matter that

was finally resolved under Eisenhower's threat of nuclear weapons use

if North Korea and China did not back down in their insistence on the

return (and likely execution) of their resistant soldiers.

Thus it was

that an armistice (not an actual treaty of peace) was signed among the

warring parties, leaving Korea rather permanently divided north and

south along a line not too far off from the original temporary dividing

line along the 38th parallel. Tensions would flare from time to time

after that, but leave the line itself intact, even down to today.

|

Early discussions (October 1951) concerning an Armistice ... but nothing was ultimately decided

At Kaesong and then at nearby Panmunjom

(located along the line of stalemate) talks began in July of 1951

between U.N. representatives and the Chinese and North Korean

representatives.

These dragged on for two years until the terms for a

cease-fire and a demilitarized zone (DMZ) were finally agreed on in

July of 1953.

|

Meeting at Panmunjom 28 July 1953 between US Army General Blackshear M. Bryan

and North Korean General Lee Sang Cho the day after the Armistice finally went into effect

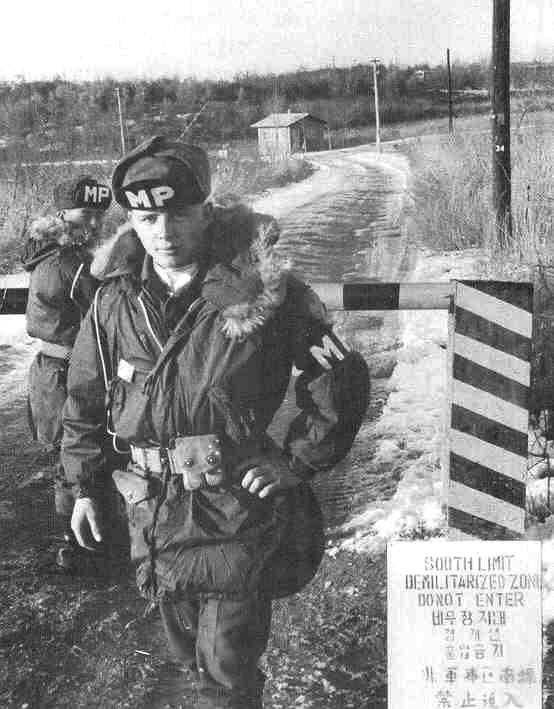

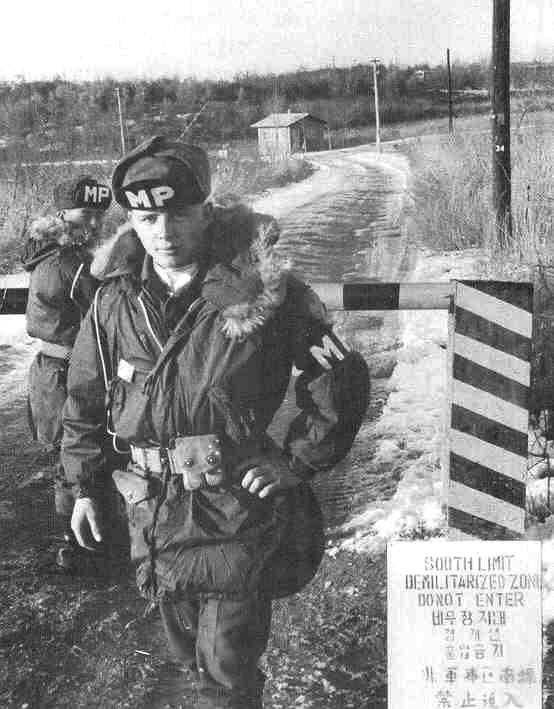

U.N. troops at the Korean

Demilitarized Zone (DMZ)

The early politics of a divided Korea

The early politics of a divided Korea The outbreak of the war

The outbreak of the war The landing at Inchon and the move of the war to the North

The landing at Inchon and the move of the war to the North China intervenes

China intervenes MacArthur is relieved of command

MacArthur is relieved of command The war drags on

The war drags on Armistice

Armistice

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges