|

|

The

war in Vietnam grows ever-darker The

war in Vietnam grows ever-darker

The

politics and diplomacy of the war The

politics and diplomacy of the war In

the meantime opposition to the war begins to mount in the US In

the meantime opposition to the war begins to mount in the USThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 191-194. |

|

|

Vietnam, and the domino theory

With Johnson taking command of American foreign policy, the long-brewing crisis in Vietnam took on major significance. T he necessity of acting boldly in Vietnam was put forward to the American people in the form of a "domino theory." This theory was that if you did not take a firm stand against aggression in one place in the region and let that nation fall to Communism, then soon the country next door would fall, then the one next to that, and then next to that, like a line of dominoes. The presumption was that Communism was a single-minded force ultimately directed from a single command center: the Kremlin in the Soviet Russian capital at Moscow. Tragically the role of nationalism and nationalist varieties within the so-called Communist camp, often in sharp conflict with each other, did not factor into this erroneous American assumption that Communism was a single-minded force. Thus arose the conclusion that America needed to take a strong stand in Vietnam, lest all the countries in Southeast Asia fall to Communism like a line of dominoes.1 The professionalization of the Southeast Asian conflict Johnson did not reveal right away what the strategy might be that he would bring into play to block the fall of the "dominoes" to Communism. But being the mechanical-minded operator that he was, one who was awed by and devoted to professionalism in the world of politics, an equally professional military engagement in the area made the most sense to him. And by that he meant heavy involvement of the American military – obviously much more professional than the Vietnam Republic's unimpressive military. But he wasn't ready to call the nation to war.2

Rather, he was hoping to keep this as a limited "police action" and

nothing more. He would attempt to pursue this war without involving the

American citizens too much – although he would be drafting their sons

for Vietnam service! He did not want the nation distracted from the

bigger priority of his Great Society program. Unfortunately, this would turn out to be a huge mistake, sending young American males off to war without enlisting the full support of American society itself. The necessity of enormous sacrifice laid on the shoulders of ordinary Americans was never explained or rewarded emotionally by the Johnson team. And thus this lack of emotional connect between a very draining war in Vietnam and an American national spirit willing to make the sacrifices required by such a war would not only handicap Johnson in what he was able to do to win in Vietnam, it would end up adding greatly to the moral-spiritual division beginning to tear the country apart at that time. The mistake of presuming that victory in war Here too, Johnson and his generals made

the classic mistake in believing that it is battlefield victories that

win wars, rather than understanding that wars are won on the basis of

one side or the other able to keep the spirits running longer than the

opposition. A war is won not on any particular battlefield but on the

ability of one side in the conflict to get the other side to want to

quit. Battles help. But economic, social, cultural factors also play

hugely in the way a war is brought to success. Military professionals

(including Johnson) involved in the Vietnam War would have a hard time

understanding this basic idea.3 The strategy Johnson and the generals came up with seemed to this inner circle itself quite manageable and rather limited in scope. American soldiers would be put ashore at various points along Vietnam's long shoreline, establish secure military positions there, and then step by step expand America's area of military control as American soldiers fanned out from each of these beachheads. Eventually all of Vietnam would thus fall under secure American military control. The plan sounded totally logical in conception. That is, after all, how wars typically proceeded in the past. And it was so very clear on the map how this simple plan would work out. Again, it seemed impossible for Americans (including the President, and even his generals) to understand the nature of the political crisis in Vietnam. The Communist enemy wore no uniforms, and in fact was indistinguishable from the people America was trying to save for democracy. Most of the people America was trying to save were Buddhist, loving neither Communism nor the Western culture Americans were trying to uphold in Vietnam. Mostly they wanted to be left alone by everyone so that they could peacefully tend their rice fields. There were of course pro-American Vietnamese, located especially in the city of Saigon and some of the other urban areas of the South. And the montagnards, the mountain people who centuries ago had originally inhabited the area but had been driven by invading Vietnamese into the mountains for survival, were big supporters of the American presence. But mostly the Vietnamese were simply proud nationalists who wanted non-Vietnamese (that would be the Americans), out of their country, along with the Communist fighters out of the North who were helping to make life in the South miserable. Saving Vietnam for democracy had little meaning to them. Thus the goals of America's involvement in Vietnam remained unclear. And the means by reaching these unclear goals were thus equally unclear. It was a frustrating war. So, contrary to Johnson's original expectations, America's strong presence in their country did not bring forth exuberant Vietnamese praising and thanking the Americans for their liberation from Communism. Instead American soldiers found themselves encamped behind barbed wire enclosures, venturing out into the countryside in search of an enemy they could not distinguish from the general population and getting shot at from behind as well as in front. There were no front lines of military progression but merely an uneasy occupation of sections of territory here and there – territory which changed hands constantly. Americans were getting killed without any visible signs of progress, except that Americans seemed to be killing more of them than they were killing of the occupying soldiers, though also there were a whole lot more of them than Americans to be killed. "Them" was not a clear concept, and Americans soon found themselves killing anything that looked suspicious, even whole villages by aerial strafing and bombing. It was an ugly sight, covered in gory detail by a watchful American press. Back home, Americans were getting very uneasy about the war. The Vets were an unshakably patriotic group, standing with the government no matter what ("my country right or wrong"). But the Boomer youth were trained hardly to see things that way. They were beginning to voice openly their opposition to the war. Why should America's youth be drafted to serve in a distant war whose morality was questionable? Soon the Boomers began to do what they had been long trained to do: fiercely protest against the political authority in Washington, whose actions to them seemed entirely wrong – even evil. In October of 1967 they gathered en masse in front of the Pentagon to call for an end to the war – meaning simply the withdrawal of all American troops from war-torn Vietnam. 1Wisely Truman had not made this error – when he swung support to America's former opponent, Yugoslavia's Communist leader Tito, when Tito resisted Stalin's attempt to take control of the Communist Party in Yugoslavia. By backing Tito, Truman helped prevent Stalin from being able to extend Soviet Russian power all the way to the Adriatic and thus to the Mediterranean Sea! 2He requested of Congress no declaration of war, but only authorization to take whatever steps necessary to stop Communist aggression in the region. He got this authorization (the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution of August 7, 1964) by exploiting the reaction of the American public to a minor incident which was rather hazy in detail and in part of dubious authenticity as it was portrayed by the White House to Congress and the nation. 3Lincoln,

back in the 1860s, well understood the demands of warfare. His generals

at first did not – until Grant and Sherman came along, two military men

who well understood the savage nature of war. Washington, who himself

was seldom a battlefield hero, also understood the challenge of war and

held up the Patriot cause through the darkest of days – refusing to

yield to the English, regardless of what they threw at him by way of

English battlefield victories.

|

Body count of NLF guerrillas

– 1962

US officer training Montagnard

troops in Vietnam – 1964

|

Barry Goldwater – unsuccessful

Republican Presidential candidate – 1964

|

Lyndon Johnson reviewing

American troops

US Marines landing at Khe

Sanh military airbase near the North-South Vietnamese border

US helicopter and troops

in Vietnam – 1965

America beginning to realize

that the Vietnam War was not going to be easily winnable –

1966

"SP4 Ruediger Richter (Columbus,

Georgia), 4th Bn., 503 Inf., 173 Abn Bde (Separate),

lifts his battle weary eyes

to the heavens, as if to ask why? SGT. Daniel E. Spencer

(Bend, Oregon) stares down

at their fallen comrade. The day's battle ended, they

silently await the helicopter

which will evacuate their comrade from the jungle

covered hills in Long Khanh

Province."

US Marines on search and

destroy mission in South Vietnam

(nearly 550,000 US troops

were in Vietnam by the spring of 1968)

U.S. artillery in

Vietnam

Peasants working in the Mekong

River Delta rice fields while bombs go off nearby

An F-4C Phantom air strike

on a Vietcong-controlled village

A village after an air

strike

A VC guerrilla captured during

"Operation Piranha" – November 1965

Vietcong on the move – May 1965

Operation Rolling Thunder

... an attempt to bomb North Vietnam into submission ...

begun in March

of 1965 and continued until just before the American presidential elections

in November of

1968

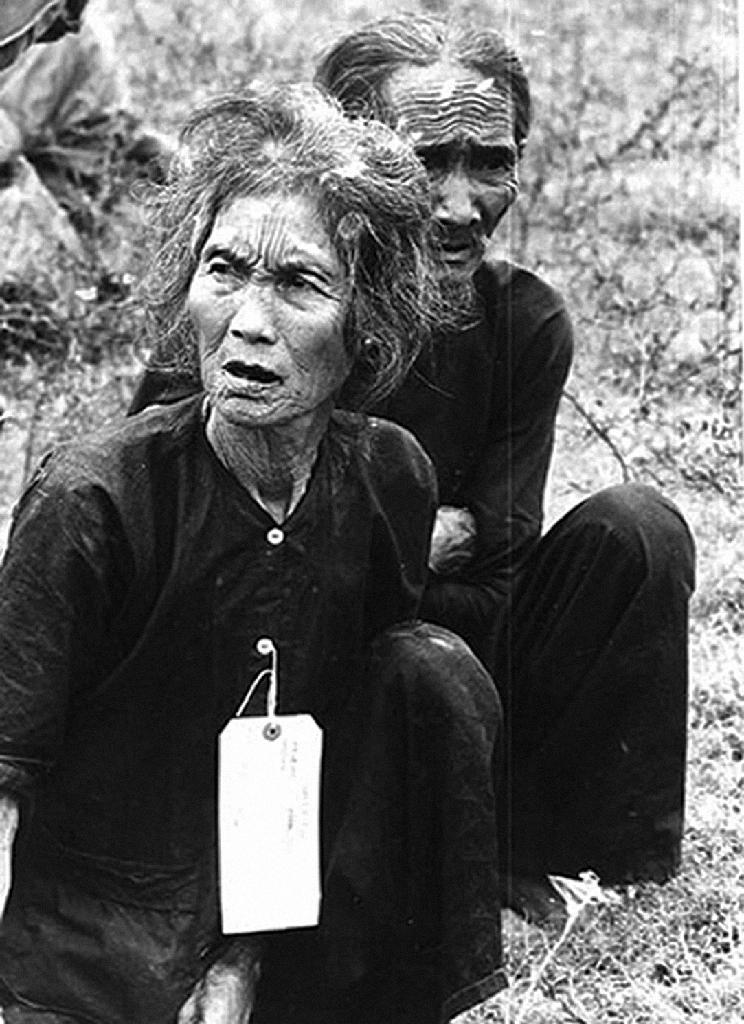

Peasants being held and questioned under suspicion of being Viet Cong supporters – 1966

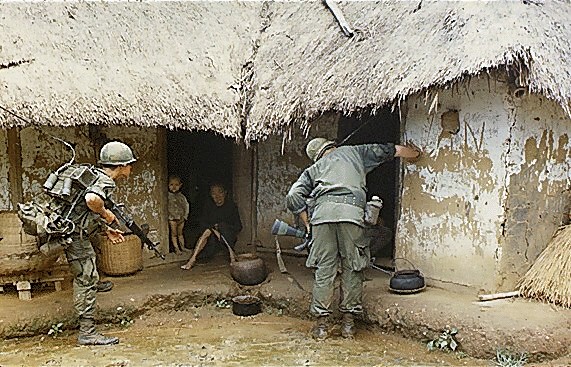

Checking a Vietnamese house in an anti-VC sweep in October of 1966

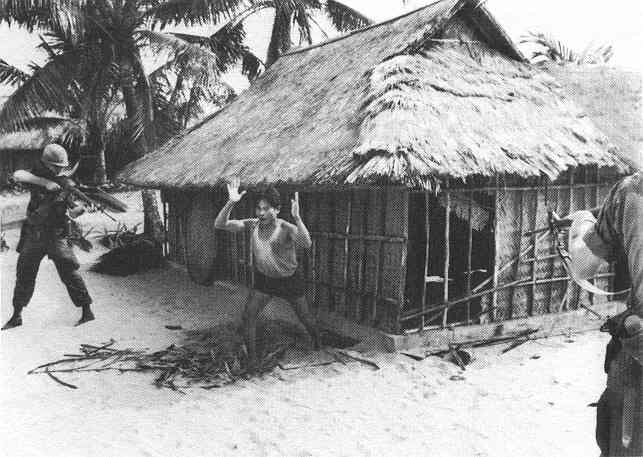

Marines capturing a VC suspect emerging from a "spider hole" behind this house – 1967

Dead Marines are stacked

on a tank near Con Thien

after hand-to-hand combat

with North Vietnamese regulars – July 1967

|

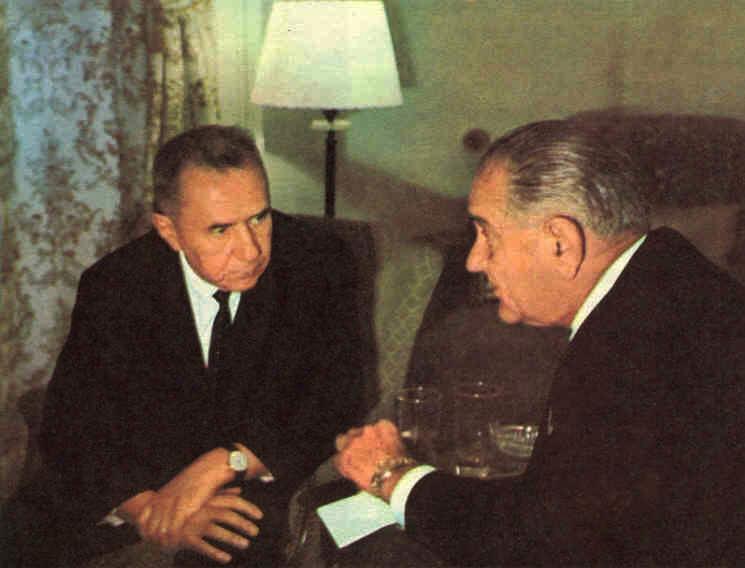

Soviet Premier Aleksei Kosygin

confers with Johnson in Glassboro, New Jersey – June 1967

Johnson confers with Soviet

Premier Alexei Kosygin at Glassboro, NJ – June 1967

Official inspection tour

of "progress" in the Vietnam war by US envoys – June 1967.

Seen here conferring are

Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker (left), Gen. Maxwell Taylor,

Clark Clifford, and Gen.

William Westmoreland

Johnson confers with Gen.

William Westmoreland and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara

July

1967

Nguyen Van Thieu sworn in

as S. Vietnamese President; Vice-President Nguyen Cao Ky

behind him October

1967

|

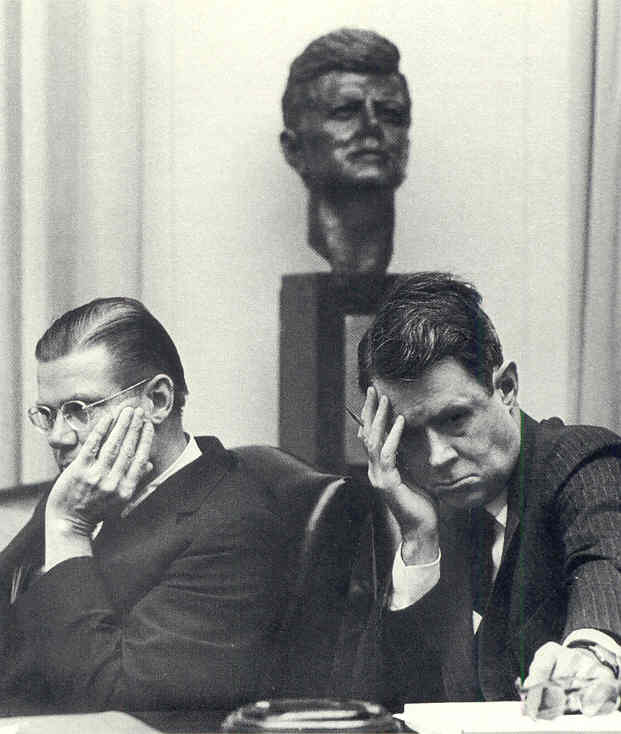

Defense Secretary Robert

McNamara and his Deputy, Cyrus Vance – May 1965

(McNamara, who had become

despondent over the war, left his position

in February of 1968 to become

chairman of the World Bank )

Anti-War demonstration in

San Francisco – April 1967

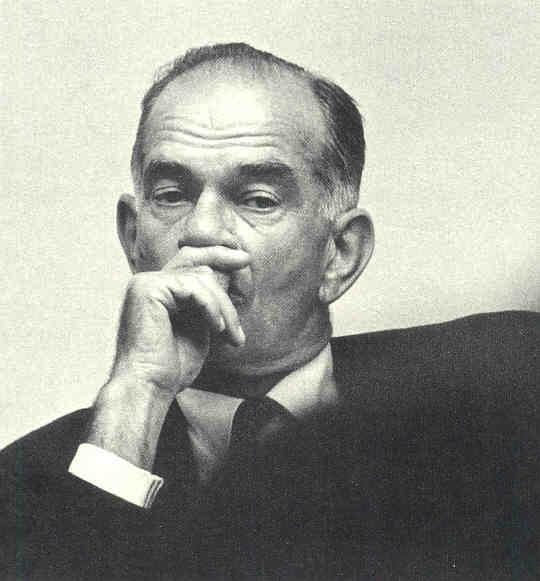

J. William Fulbright – Democratic

Chair of Senate Foreign Relations Committee (1960s)

Senator J. William Fulbright

(D-Ark) Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Giving the Vietnamese War

a scrutiny which made LBJ very uncomfortable

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges