6. THE SHAPING OF A NATION

JACKSONIAN CULTURE

| CONTENTS

De Tocqueville's Democracy in De Tocqueville's Democracy in

America

The industrial revolution continues The industrial revolution continues

forward in the East

Individualism and isolation of life in the Individualism and isolation of life in the

opening West

Unitarians and Deism also flourish in Unitarians and Deism also flourish in

the East

The Second Great Awakening The Second Great Awakening

The Mormons The Mormons

The Larger Christian mission The Larger Christian mission

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 230-247.

|

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1820s |

Americans prove themselves to be highly inventive – materially and spiritually

1820s Inspired by the dedication of the highly active Bishop Francis Asbury (1790s to 1816), Christian "Methodism" spreads

quickly ... especially in the isolated and hardscrabbled western

frontier lands – where hundreds of circuit riders work feverishly to spread the Christian Gospel

Finney

turns religous camp meetings into something of a religious science ...

his carefully engineered religious program soon followed by other revivalists

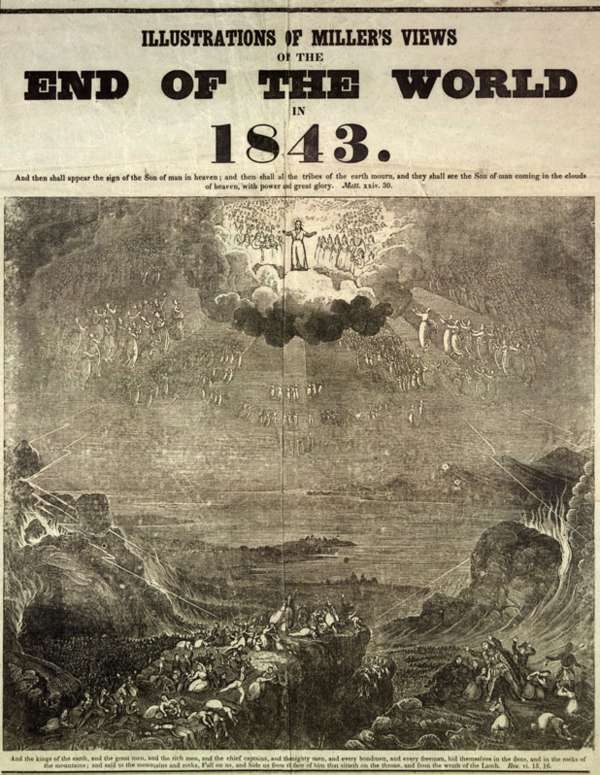

Millennialism (expecting the 2nd coming of Christ) infects the

American religious heart everywhere

Thus the "Second Great Awakening" (actually started in the 1790s)

gathers momentum .. most notably in Western New York (later

termed the "Burned-Over District")

This is

coupled with the growth of various Christian organizations uniting

various Protestant denominations:

American Bible Society, American Sunday School Union, Board of Foreign Missons,

Anti-Slavery Society, American Temperance League (anti-alcoholism), etc.

1825

The 8-year project of the Erie Canal is completed, opening

a water route from New York City all the way to Lake Erie in the Great

Lakes region

1828

The first segment of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad is

started up (completed in 1830) beginning a rush to build railroads that

will continue unabated through

the entire 1800s

|

| 1830s |

This inventive momentum carries over into the 1830s

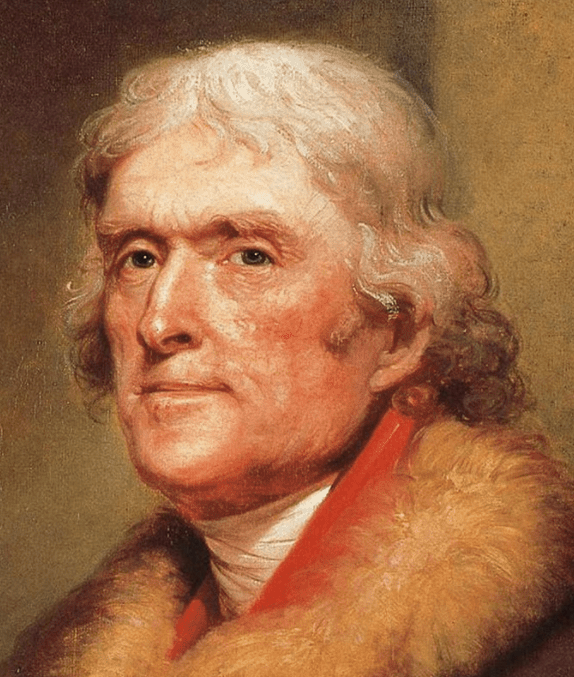

1830s Unitarianism and Deism also show strong growth in America (supported greatly by Jefferson)

1830 Joseph Smith publishes the Book of Mormon, beginning the Latter Day Saints (LDS or "Mormons") ... also birthed in the "Burned Over District" of New York!

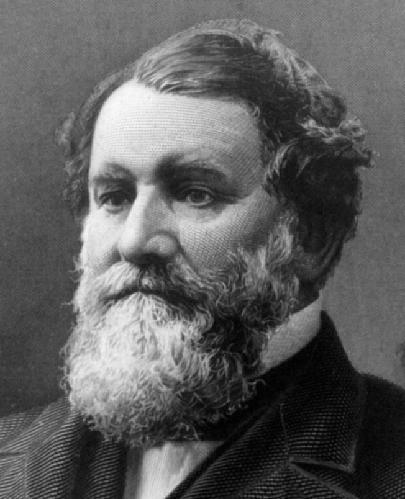

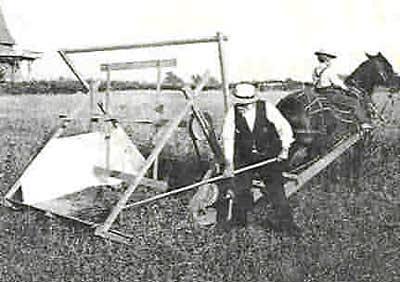

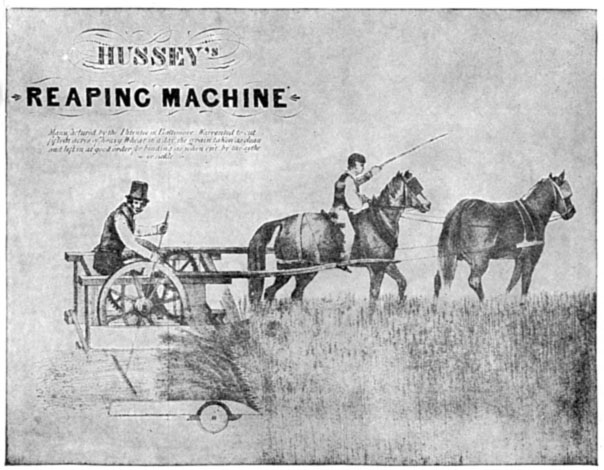

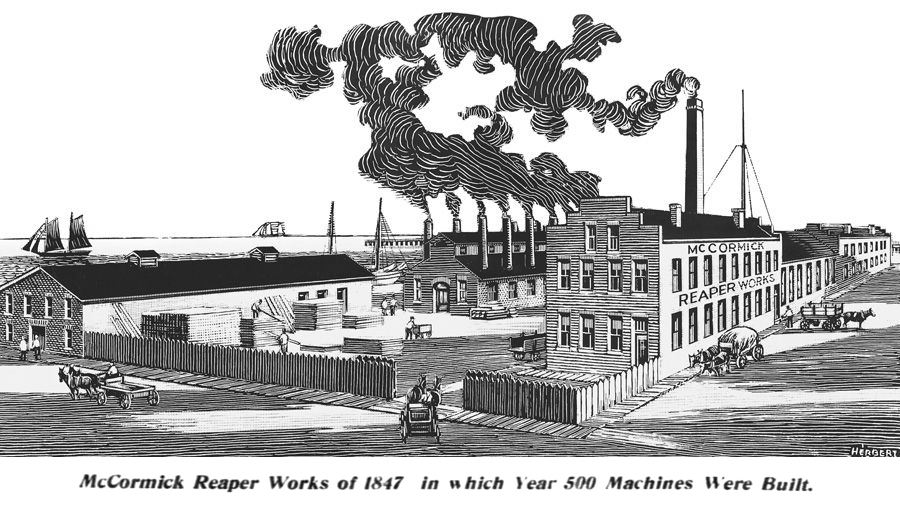

1831 Cyrus McCormick demonstrates his new mechanical reaper ... revolutionizing the farming industry

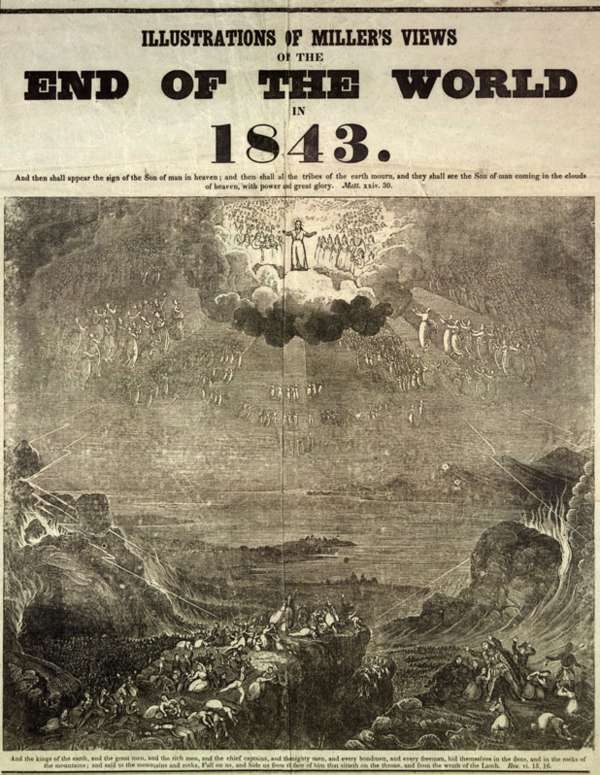

1833 William

Miller (also based in the Burned Over District) predicts Christ's

second coming to take place in 1844

... birthing what eventually becomes the Seventh-Day Adventist

movement.

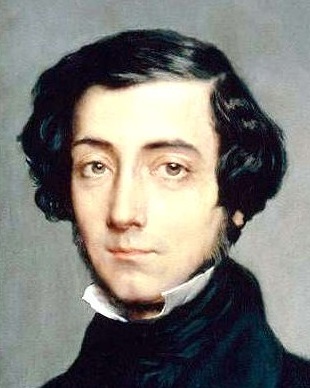

1835

The Frenchman Alexis de Toqueville will detail what he observes of the

unique America spirit in his two volume study, Democracy in America (1835/1840)

Late 1830s

Emerson (and his neighbor Alcott) propose a Higher or more

"Transcendental" religion ... one drawing much of its character from

Hinduism

|

DE TOCQUEVILLE'S DEMOCRACY IN

AMERICA |

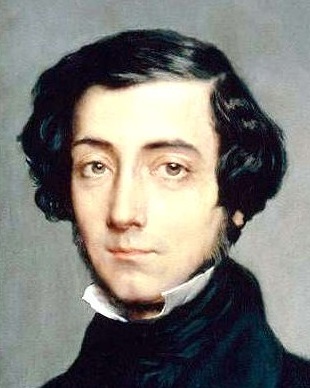

Alexis de Tocqueville – author of Democracy in America (two volumes: 1835-1840) offering a French perspective on America's democratic society

... admiring of Americans' egalitarian spirit and restless individualism

but negative about Americans' still-Puritan personal ethics

and concerned about where American slavery was taking the country

|

De Tocqueville's Democracy in America

In 1831 the Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville

arrived in America, ostensibly to study the American prison system. But

he and his associate Gustave de Beaumont were truly more interested in

studying the American society in general, a subject of great interest

to the French. Tocqueville published in two volumes the results of his

study as Democracy in America, appearing in 1835 and 1840 at the height

of the Jacksonian era. It provides an incredibly insightful view of the

American culture by one standing outside that culture.

He noted the hugely individualistic spirit of the

typical American and the restlessness of the American heart, which was

already looking for the next challenge before it had completed the work

on a previous challenge. He also noted the spirit which defended the

basic equality of all (Whites), ever-ready to challenge presumptions of

superiority on the part of others. He correctly attributed the origins

of this egalitarian spirit to the Puritans of New England as well as

the principle of the sovereignty of the people founded in the early

Puritan covenants and state constitutions.

But he also noted the contradictions to all this

posed by the agonizing question of slavery. Also, from a Frenchman's

view with its more liberal attitudes toward marriage and the sexes, he

was distressed at how rigid were the sexual roles assigned to men and

women, both in and out of marriage (but this also was a Puritan legacy,

unknown in France). He was also concerned about the dangers of

democracy turning into a tyranny of the ignorant majority, unrestrained

by the more enlightened understanding of social dynamics by society's

more polished and better educated social elite. And he correctly

predicted the tragedy of war that would eventually occur over the

wrenching issue of slavery. In short, he described clearly the good and

the not-so-good of Jacksonian America, at least as the French

understood the social ideas of good and bad.

|

THE

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

CONTINUES FORWARD IN THE

EAST |

|

The restlessness of the American heart that

Tocqueville noticed was clearly obvious in the incredible amount of

industrial activity – and innovation – pushing the American economy

ever-forward. The development of the steam engine permitted extensive

mechanical operations to take place where no water power was readily

available to turn the wheels of industry's many new mills appearing

across the North (by 1840 there were some 1,200 cotton mills in

operation, mostly in the American Northeast).

Foodstuffs, raw materials, and even finished goods were constantly on

the move in America – along the turnpikes and the many canals being

laid out across the East. By 1818 the National Road had been completed

linking the American East at Baltimore and Philadelphia with the Ohio

River valley at Pittsburgh and thus providing access to the American

interior all the way to the Mississippi. With the development of steam

power,1 paddlewheel boats able to go both ways on the great rivers of

the American interior were soon moving vast amounts of produce from the

West back to the East – and people and their goods headed to new lives

in the West.

The Erie Canal

Not to be outdone by Baltimore and Philadelphia,

New York, under the direction of its industrious Governor DeWitt

Clinton, decided in 1817 to dig a canal from the Hudson River at Albany

all the way to Lake Erie at Buffalo, thus gaining access to the

American interior by way of the Great Lakes. The 363-mile project was

open for business by 1825 (which turned out to be a highly profitable

venture!).

The first railroads

In 1827 the town fathers of Baltimore, seeing

water traffic outbid their wagon road, decided to investigate the

possibilities of laying a railroad, similar to one under development in

England. In 1828 they laid the first rails and by 1830 they had

completed the first portion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Then, not to be outdone by New York with its Erie

Canal and Baltimore with its railroad, Massachusetts in 1830 and 1831

decided to undertake the building of a railroad across the low

mountains to the West, to link Boston with Albany on the Eire Canal,

completing the program by 1842.

Eight years later (1850) almost 3,000 miles of rail line then connected

New England towns with even the Great Lakes. And by 1852 the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad was the first Eastern railroad to reach the Ohio

River. This was such a boon to business, that the following year (1853)

the mighty New York Central Railroad was formed by consolidating ten

smaller railroad companies.

Meanwhile in the South, in 1828 the town fathers

of Charleston decided to open up their city by rail all the way south

to the Savannah River (to gain some of the trade which was prospering

rival city Savannah tremendously). When it was completed in 1833 it was

at that point the world's longest railroad. Eventually the South

extended the reach of its rail system, by 1851 reaching Chattanooga on

the Tennessee River and from there ultimately Memphis on the

Mississippi River.

The mechanical reaper revolutionizes agriculture

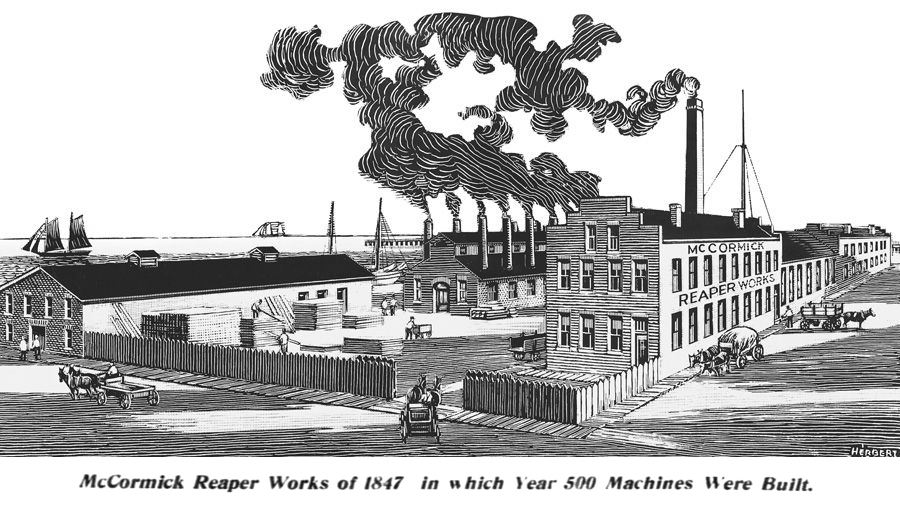

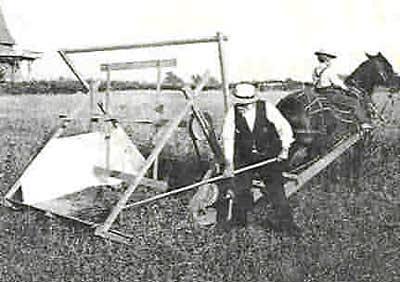

In 1831 Cyrus McCormick held a demonstration of

his new reaper, which with one mule and one driver could harvest wheat

at six times the rate of a single farm worker.2 Needless to say, the

reaper now became not only highly sought after, it soon became standard

equipment on the large farms of the American Midwest, which themselves

were industrial enterprises rather than just mom-and-pop operations

designed merely to support a single family.

1In August of 1807 Robert Fulton's steam-driven dual paddlewheel North River Steamboat

made the amazing 150-mile boat trip up the Hudson River from New York

City to Albany in 32 hours of actual travel (not counting stops along

the way).

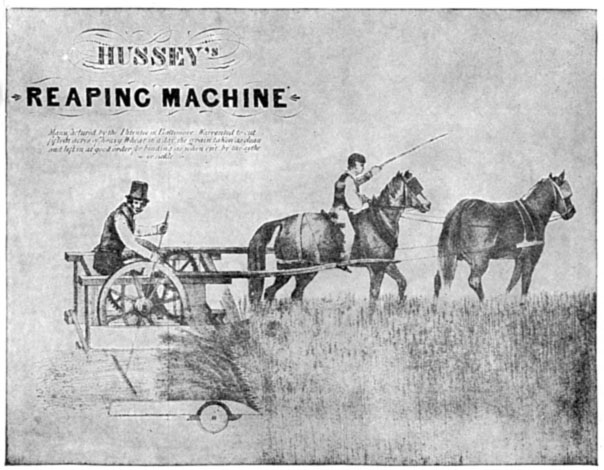

2McCormick's

claim to have invented the reaper was challenged by another inventor,

Obed Hussey, whose 1833 invention was in fact a better machine. The two

improved their models and competed until Hussey was finally driven out

of business.

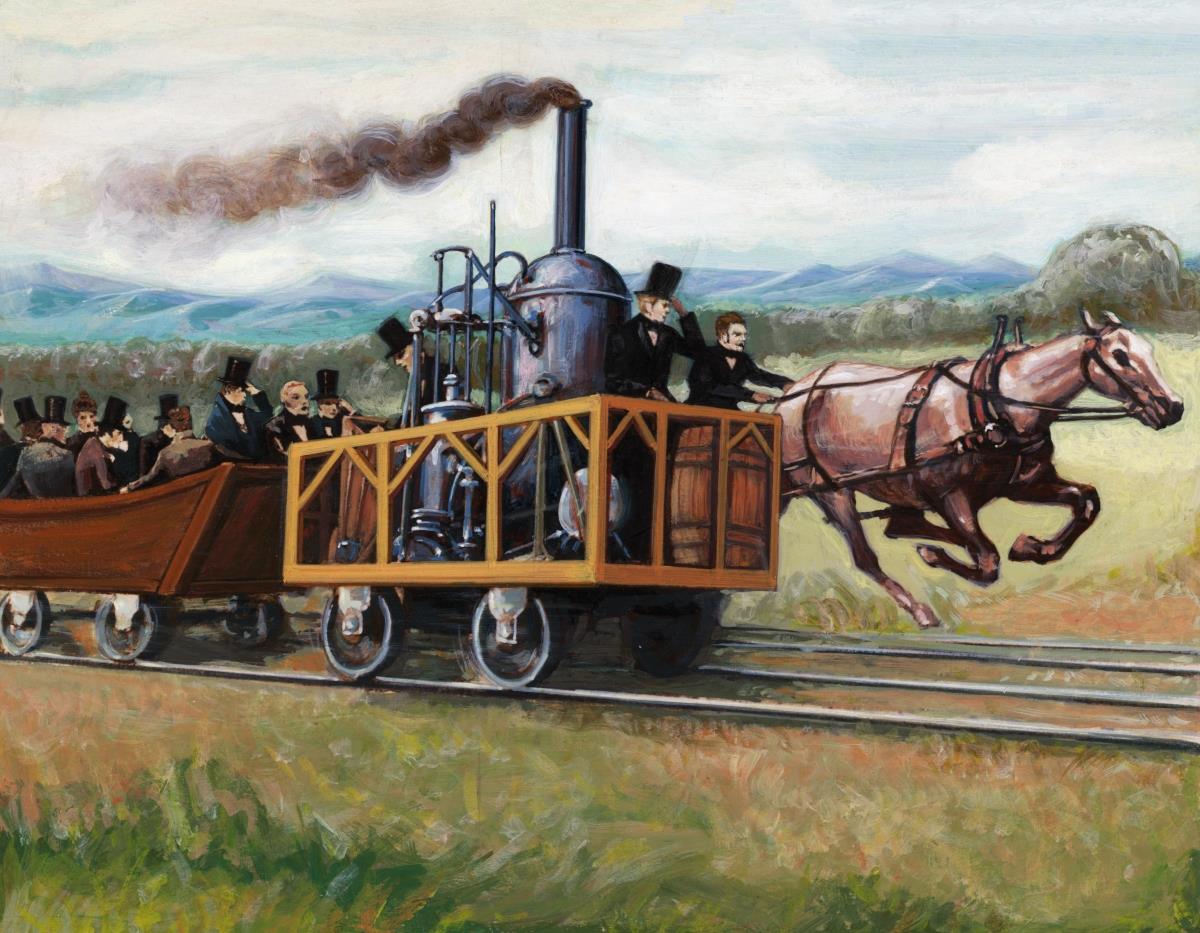

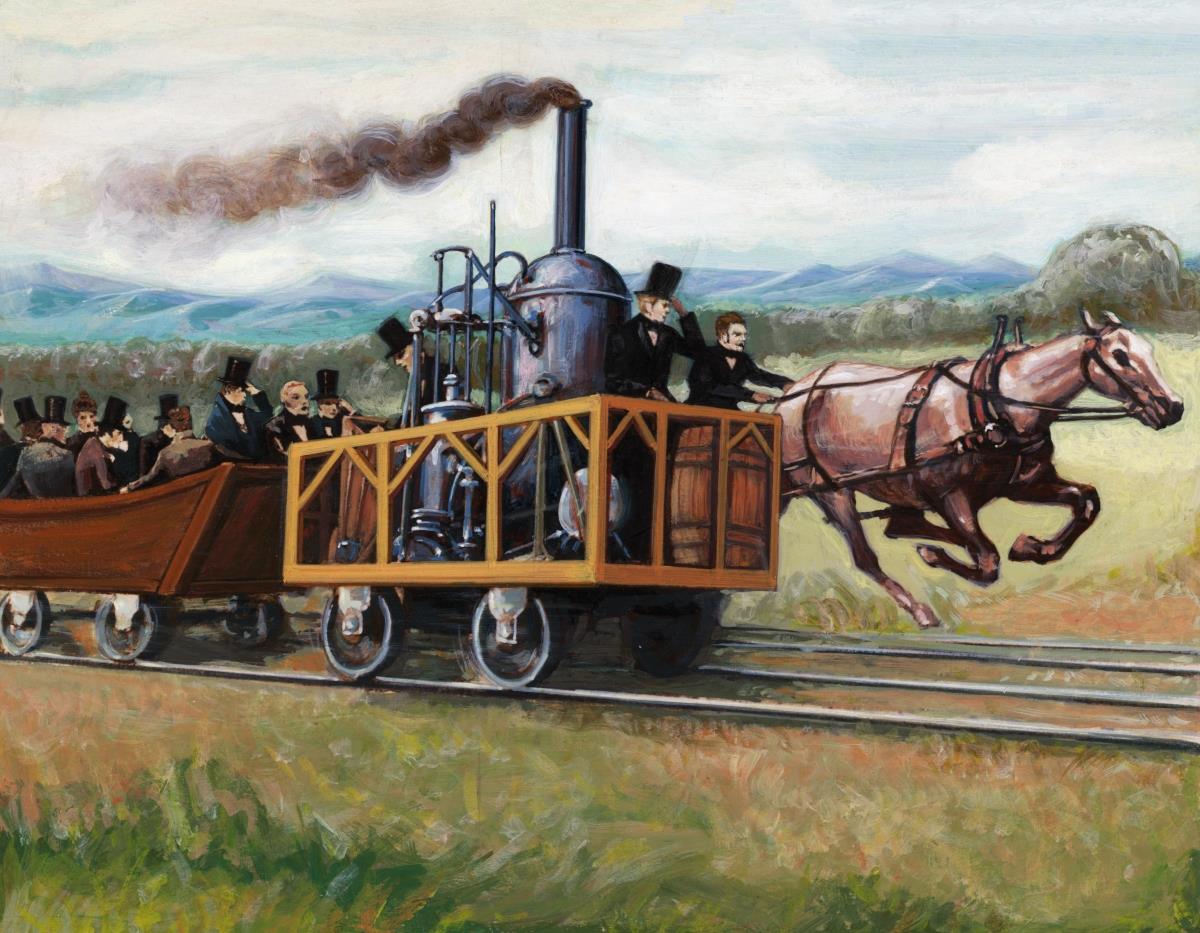

Steam-driven Tom Thumb racing a horse (August 1830)

The locomotive pulled well ahead of the horse ... until a belt broke in the locomotive, ending the race.

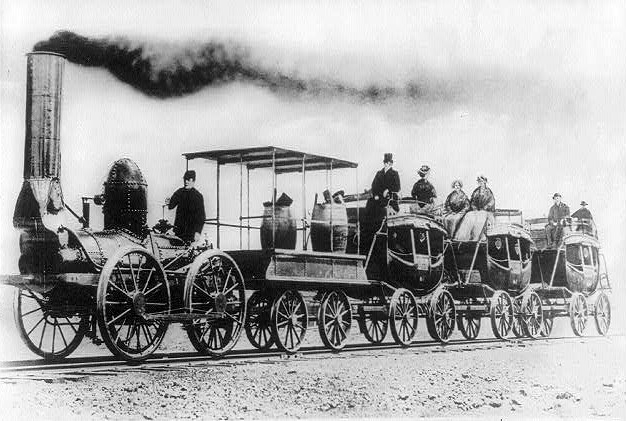

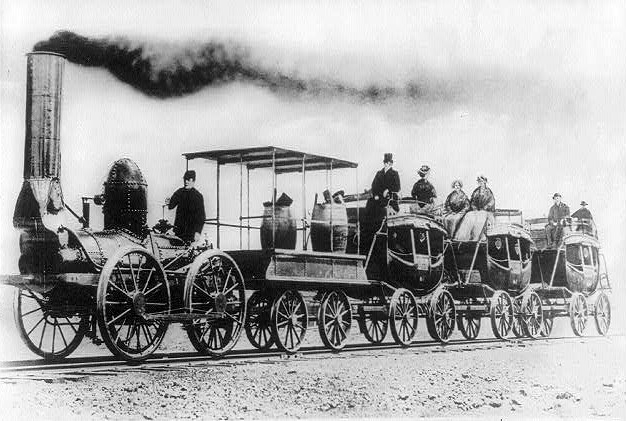

A very early American steam-driven locomotive, the De Witt Clinton – 1831

(named after the New York

governor)

Library of

Congress

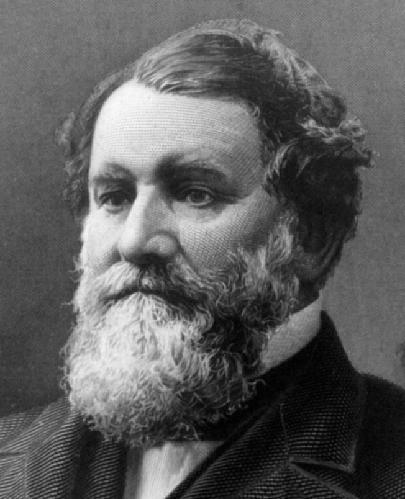

Cyrus McCormick

His reaper helped revolutionize the American farming industry

A demonstration

being given on the operation of the McCormick reaper (1831)

In competition with McCormick was the reaper invented by Obed Hussey (1833)

INDIVIDUALISM AND ISOLATION OF LIFE IN THE OPENING

WEST |

|

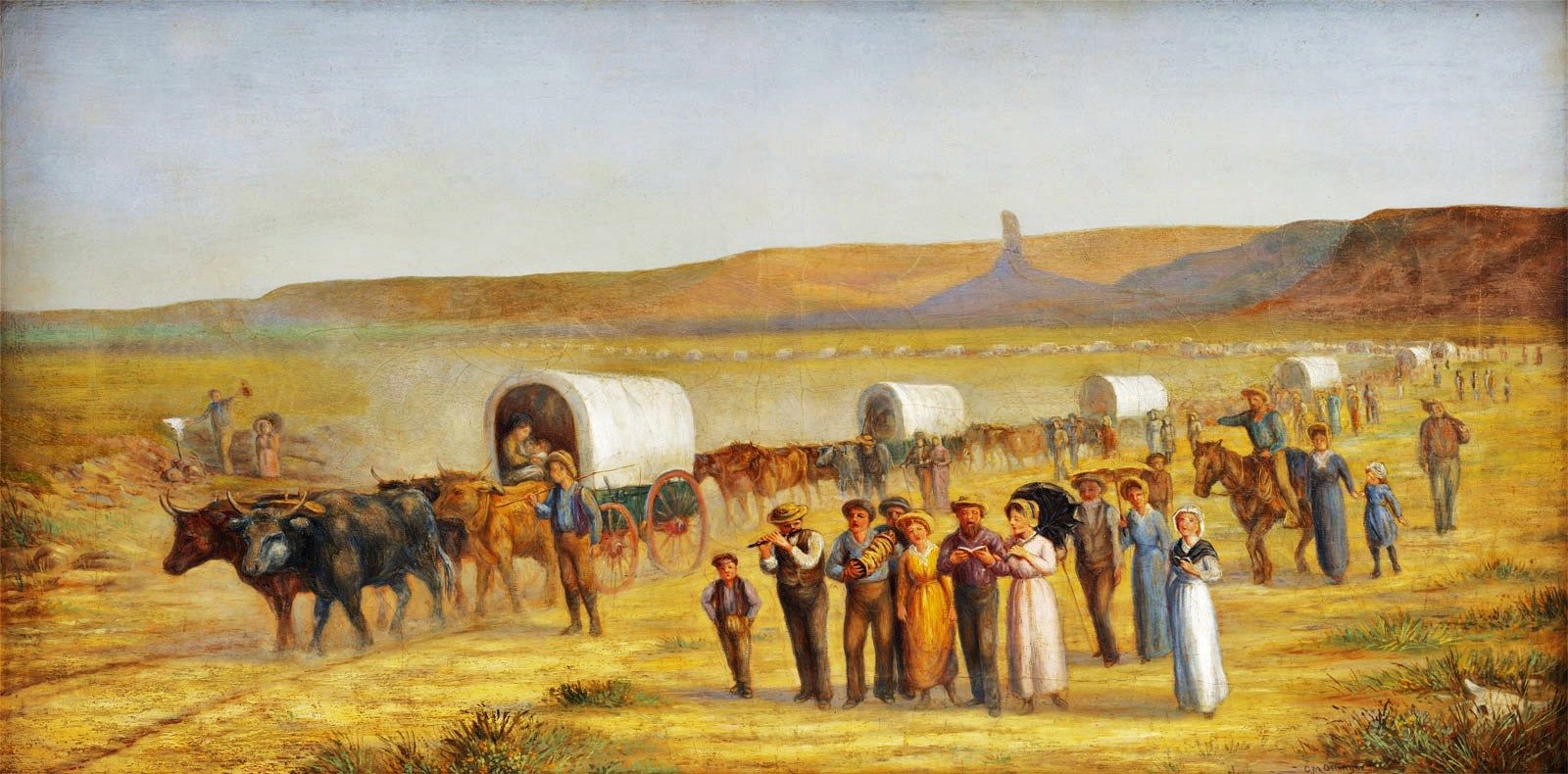

The American world was changing fast, and change itself produced its own problems, psychological as well as physical.

On top of all this change, it was obvious by 1830

that the land was playing out in the East. The stony soil of New

England had never been that great and – stressed by a rapidly expanding

population – the region was unable to sustain a stable agricultural

existence. So the 1830s and 1840s saw streams of New Englanders heading

West across the Appalachian Mountains and down the Ohio River to find

new homes in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and across the

Mississippi into Missouri. Likewise, the cotton farms of Virginia, the

Carolinas and Georgia were playing out, sending settlers West into

Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and even into the northern Mexico

territory of Texas.

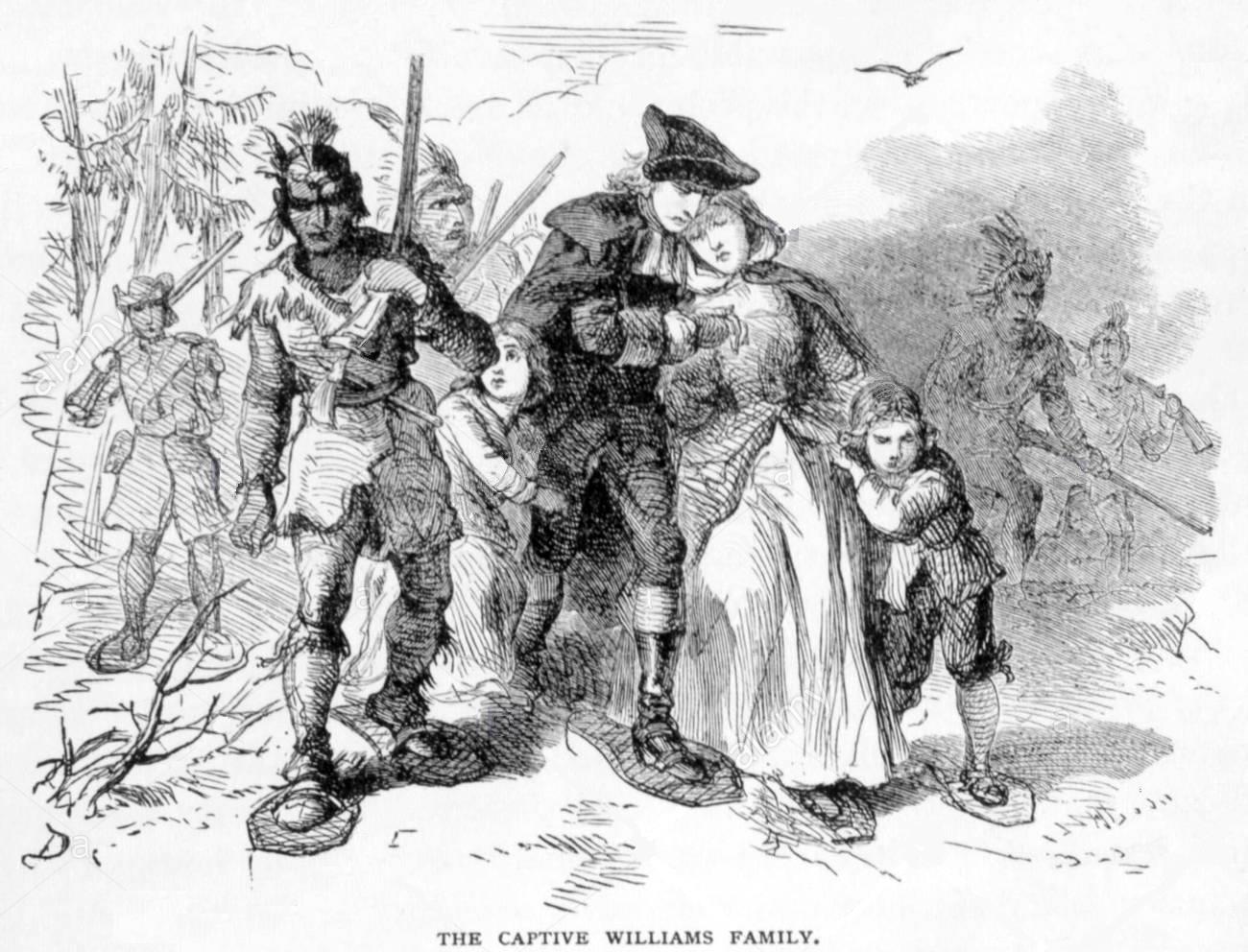

Unlike the planned movements and settlements of

the Puritans two centuries earlier, there was no organization or

coordination to this movement. Individuals just simply up and moved in

the hope of starting a new life in the West. But life in the West

proved to be isolating, and dangerous under the constant threat of

Indian attack.3 Yet such a life produced highly independent and

self-sufficient Americans, hunters and riflemen, well able to secure

meat from nature, and prepared to fend off the dangerous Indian.

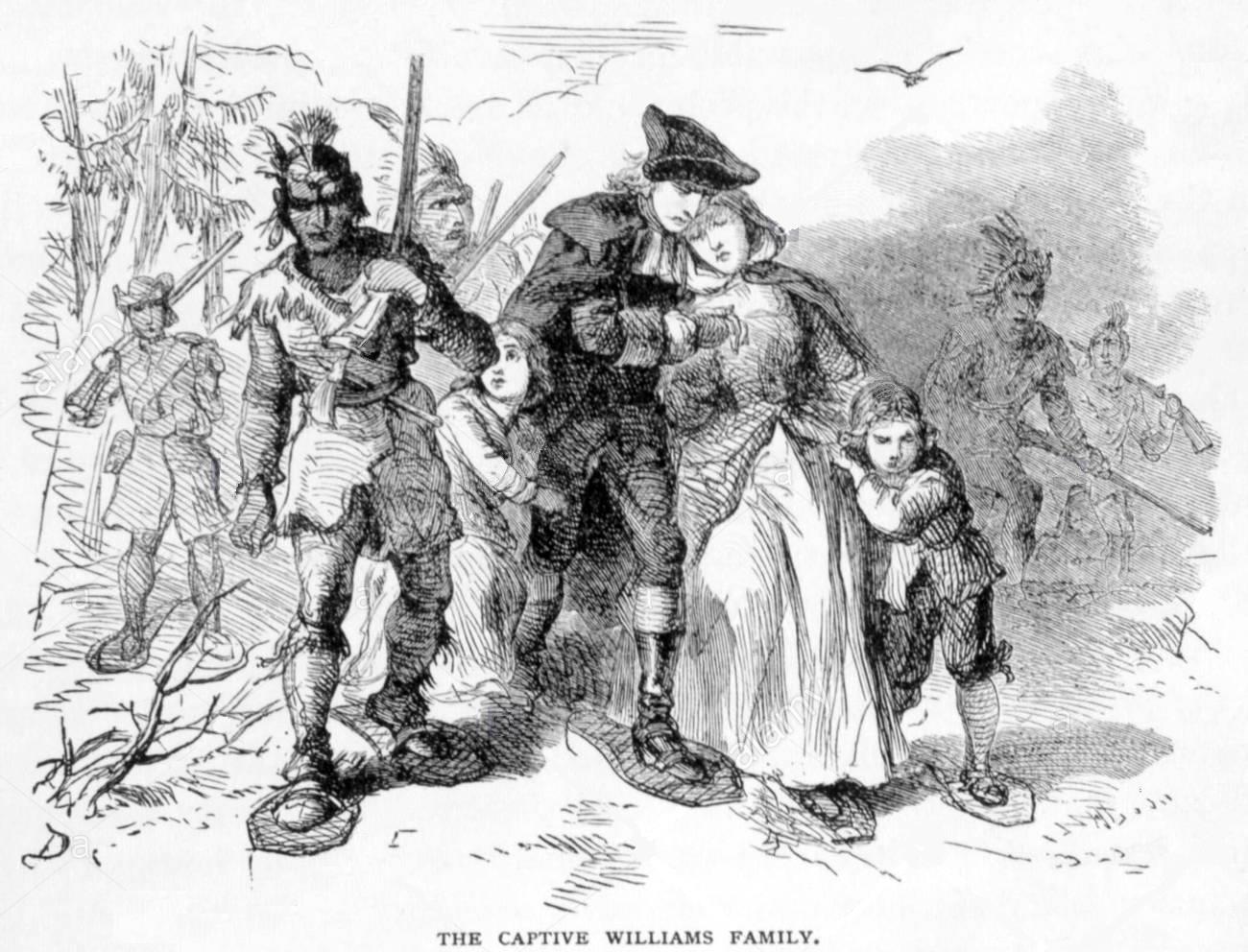

3The

results were always murderous for men, women and children, or worse,

torturous, because Indians loved to gather to watch their captives

writhe in carefully administered pain until they finally expired.

As

the lands of the East filled up and the soil got overworked through the

generations, streams of Anglos headed westward, looking for new land to

set up their homes

Life on the frontier was very, very tough

And there was always the matter of the Indians ... who understood this land to be theirs – not up for giveaway to the intruding Anglos

Indian raids were of course common on the frontier

And Indians played by their rules, not the Anglo rules of warfare

Reverend John Williams and his family taken captive

UNITARIANISM AND DEISM

ALSO FLOURISH IN THE

EAST |

|

Unitarianism and Deism flourish in the East

At the same time, for others, especially those

living along East-coast America, a comfortable small-town life

(dependent on an economy other than just agriculture) seemed to have a

natural peace and prosperity to it. Not surprisingly, life took on a

more rational character, thus stepping back from its previous fervency

in its Christian spirituality. Americans, especially among the more

leisured professional classes, found themselves less interested in what

God might do in their lives and more interested in what they might

achieve for themselves under this more rational social realm emerging

around them.

They did not abandon Christianity, because being Christian was

understood to be the same as being civilized. But the faith component

(trust in God as the essential higher power in their lives) was

disappearing. Its place was being taken by a rational morality, a key

part of Enlightenment Humanism that was sweeping intellectual circles

at the time, in America as well as Europe. Such Humanism usually

claimed the moral teachings of Scripture, especially the teachings of

Jesus, as its Christian foundation. But in the end, no such connection

was absolutely necessary, for these were self-evident truths that any

rational person would understand as the foundation of any life well

lived (French revolutionaries had gone so far as to disdain even this

slender Christian connection with their utopian Idealism).

Once again (as in the enlightened days of the late

1600s and early 1700s) enlightened Americans of the early 1800s were

convinced that Human Reason was vastly superior to the pre-scientific

superstitions about life held by simpler Americans – Americans who were

intellectually unable to shake off the irrational beliefs about people

walking on water and raising the dead back to life. The enlightened

ones were easily disdainful of those who clung emotionally to a

religion drawn from a darker past. Of course, they failed to notice

that their new Rational Humanism was no newer than the story of Adam

and Eve's fall in the Garden of Eden or the long Biblical narrative

about the repeated wandering of ancient Israel away from the counsel

and discipline of God – and its tragic results.

Christian Unitarians

In the early 1800s a huge split occurred within

the Congregationalist churches of New England, a split that ultimately

came to center on the professorship of theology at Harvard College, a

position which remained empty from 1803 to 1805. When the position was

finally awarded to the Liberal Henry Ware, the conservative Calvinists

left Harvard and founded the Andover Seminary. There they would be

joined by the more evangelical members of the New Divinity4 group.

Meanwhile, Harvard College moved off more strongly in the Unitarian

direction.

Inspired by a sermon preached in Baltimore in 1819

by Boston pastor William Ellery Channing, entitled "Unitarian

Christianity," a sermon that found itself well-received among numerous

New Englanders, the Unitarian movement began to grow rapidly,

particularly among a large number of (mostly Congregationalist)

pastors. This soon (1825) led over a hundred Unitarian pastors, again,

mostly from New England, to come together to form the American

Unitarian Association, in part to undo the Calvinism that had earlier

formed the foundations of the New England Congregationalist churches.

Their goal was to bring Christianity more in line with the recent

discoveries of science, and with simple Humanist logic that found much

of the traditional Biblical claims of Christianity to be completely

unbelievable, most notably about man's inherent sinfulness, and need of

repentance and renewal by the Holy Spirit. They proposed a simpler

formula of good works undertaken by a kindly heart as the goal that a

single God (the one and only God) set out for all mankind. In taking

this position, they were certain that they were strengthening the

foundations of a more progressive Christian religion, one that promised

to underlie a newly-arising and fast-developing post-Trinitarian

American society and culture. Inspired by a sermon preached in Baltimore in 1819

by Boston pastor William Ellery Channing, entitled "Unitarian

Christianity," a sermon that found itself well-received among numerous

New Englanders, the Unitarian movement began to grow rapidly,

particularly among a large number of (mostly Congregationalist)

pastors. This soon (1825) led over a hundred Unitarian pastors, again,

mostly from New England, to come together to form the American

Unitarian Association, in part to undo the Calvinism that had earlier

formed the foundations of the New England Congregationalist churches.

Their goal was to bring Christianity more in line with the recent

discoveries of science, and with simple Humanist logic that found much

of the traditional Biblical claims of Christianity to be completely

unbelievable, most notably about man's inherent sinfulness, and need of

repentance and renewal by the Holy Spirit. They proposed a simpler

formula of good works undertaken by a kindly heart as the goal that a

single God (the one and only God) set out for all mankind. In taking

this position, they were certain that they were strengthening the

foundations of a more progressive Christian religion, one that promised

to underlie a newly-arising and fast-developing post-Trinitarian

American society and culture.

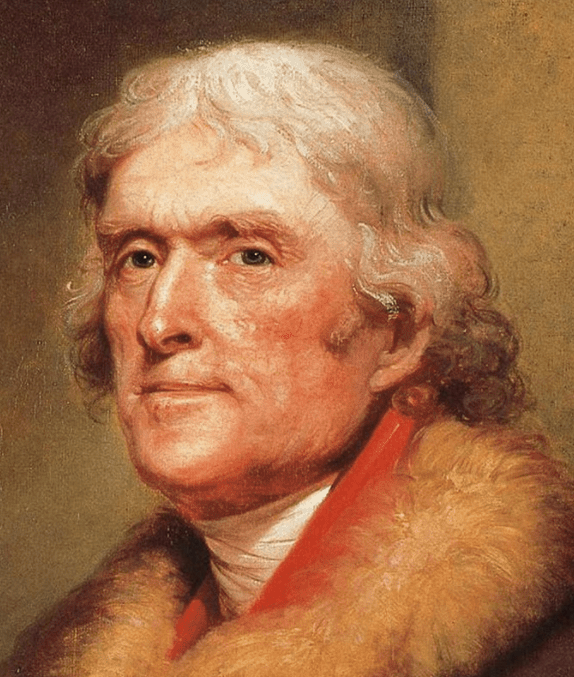

Jefferson

Another individual to figure big in this rising

Humanism around this same time (but now in his later life) was Thomas

Jefferson. In 1822 Jefferson wrote his friend Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse

attacking the foundations of traditional Christianity, pointing out in

particular the ancient apologist Athanasius and the more recent Calvin

as false shepherds and usurpers of the Christian name

teaching a counter-religion made up of the

deliria of crazy imaginations, as foreign from Christianity as is that

of Mahomet. Their blasphemies have driven thinking men into infidelity.

In that same letter Jefferson (who had published

an updated Bible eliminating all the miracle stories and focusing only

on the moral teachings of Scripture) professed that the simple

doctrines of Jesus (to love the only God with all one's heart and one's

neighbor as oneself) had been perverted by adding Platonizing doctrine

(Jefferson did not like Plato very much either) most evident in

Calvinist dogma.

But he was confident that such dark days were becoming a thing only of the past. Thus he states:

I rejoice that in this blessed country of free

inquiry and belief, which has surrendered its creed and conscience to

neither kings nor priests, the genuine doctrine of one only God is

reviving, and I trust that there is not a young man now living in the

United States who will not die a Unitarian.

For those living in the comfort of a secure

existence and untroubled by enemies or economic hard times, the promise

of the Enlightenment seemed to be above and beyond all serious questioning.

4A

major leader in the New Divinity movement was the religiously

conservative Yale College president Timothy Dwight, who worked very

hard to head off the Deism and Unitarianism spreading among the New

England clergy. Dwight was also the head of the Federalist Party in

Connecticut and an early supporter of the inter-faith American Board of

Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABDFM) created in 1810.

The Unitarian Thomas Jefferson detested the Calvinism of old (Puritan) America

On a hilltop in

rural Virginia, Jefferson spent himself into near bankruptcy building

his Monticello mansion into the place of ultimate human perfection (his

physical "bubble")

|

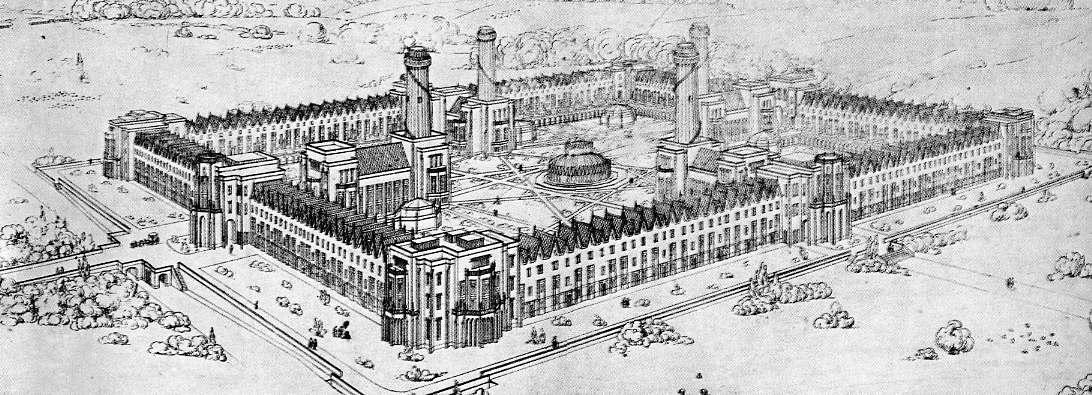

Robert Owen and his communitarian or socialist experiments in America

Right in line with this rising Humanist Idealism

were many experimental communities set out in America to show how a

perfectly designed social order could produce unprecedented prosperity

and happiness. One of the most active of such idealists was the

Scottish social philosopher, Robert Owen. He actually set up a number

of such utopian societies in America. But the most famous of these, the

one he put his heart and soul into, was his New Harmony community, set

out in the frontier land of Indiana. Owen bought the land in 1825 from

a community that had also, under the leadership of the Lutheran Pietist

George Rapp, attempted a similar experiment in perfect Christian

Socialist living, a Harmony project that failed because of the

inability of the German immigrants to live up to Rapp's great hope for

them. Right in line with this rising Humanist Idealism

were many experimental communities set out in America to show how a

perfectly designed social order could produce unprecedented prosperity

and happiness. One of the most active of such idealists was the

Scottish social philosopher, Robert Owen. He actually set up a number

of such utopian societies in America. But the most famous of these, the

one he put his heart and soul into, was his New Harmony community, set

out in the frontier land of Indiana. Owen bought the land in 1825 from

a community that had also, under the leadership of the Lutheran Pietist

George Rapp, attempted a similar experiment in perfect Christian

Socialist living, a Harmony project that failed because of the

inability of the German immigrants to live up to Rapp's great hope for

them.

But anyway, what textile manufacturer Owen was

proposing to do in his New Harmony had nothing to do with Christianity.

A huge effort was made to make his New Harmony the perfect setting of

purely Secular economic and social perfection. While Owen went around

to promote support elsewhere for his New Harmony project, he left its

supervision to his sons. They in turn ran into all sorts of

difficulties when well-intended and not so well-intended individuals

flocked to the project, a project that was designed to become

self-supporting through the industrial enterprises Owen attempted to

start up there. Some were willing to accept the responsibilities

required of this communal (Socialist) venture. Many were not. Chaos

quickly set in. Ultimately no moral structure (other than a breezy

Humanism) underlay the project. Owen himself was strongly

anti-Christian, and strongly pro-Humanist, but like all Humanists,

could never figure out how to get a free people to accept social

responsibilities on the basis of their own instincts. Other prominent

Humanists visited and offered counsel to the community. But they got no

further in getting a true social order up and running. Two years later

(1827) the Owens had to abandon their project – without having learned

anything in the process.

|

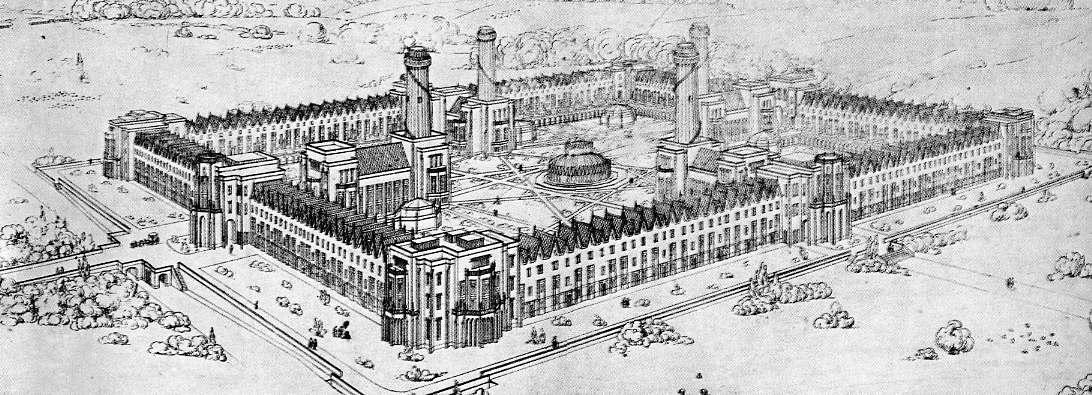

Robert Owens' proposed "New Harmony"

|

Emerson and the Transcendentalists

Another version of this development was found

among the Transcendentalists, who reached well beyond the purely

rational world of the Unitarians and other Humanists with their

mystical quest for the Divine as a higher order of disciplined thought.

They sought, through different forms of spiritual discipline, to

embrace Divinity both in a oneness with nature and a sense of reaching

beyond even the natural. They sought to be as fully human as possible

so as to find the Oneness of Divinity as fully as possible. They too

tended toward lofty communalism in the hope of reaching beyond the

coarse nature of selfishness and sin, to find a more perfect human

harmony.

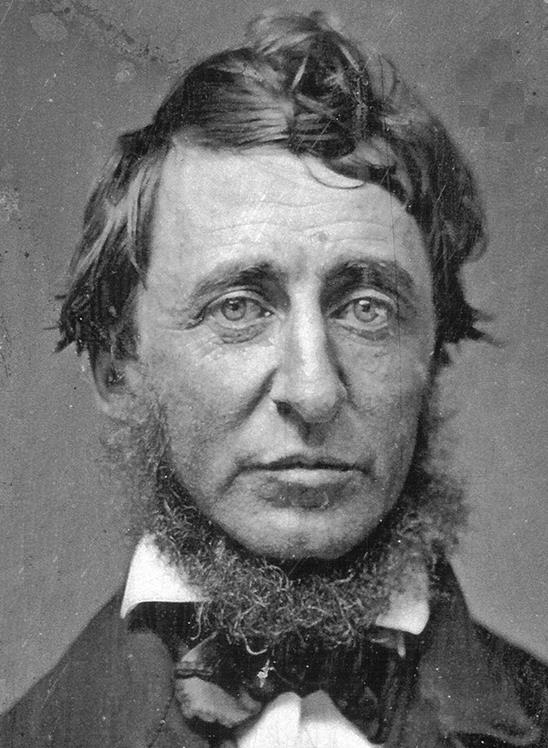

Another

group of intellectuals of the day were the "Transcendentalists" who

dreamed of a coming world of similar perfection ... but one based more

importantly on the simplicity of the pure human spirit in close touch

with the forces that direct the universe

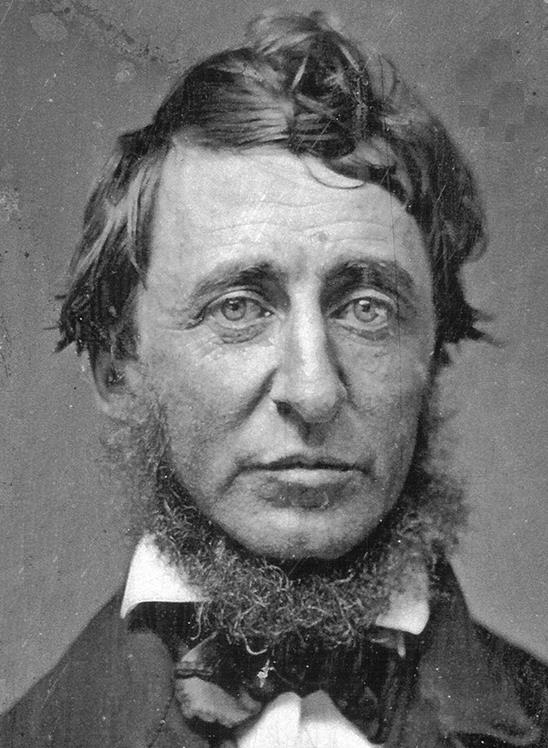

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Henry David Thoreau

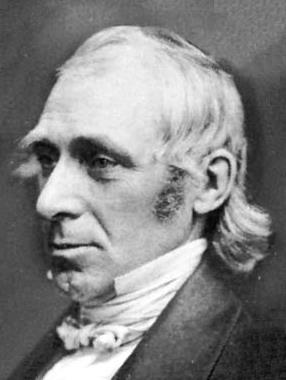

Amos Bronson Alcott

|

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Amos

Bronson Alcott (father of novelist Louisa May Alcott) were neighbors in

Concord, Massachusetts, who set the pace of Transcendentalism. Thoreau

attempted to find serenity in two years (1845-1847) of relative

isolation in the woods at Walden Pond, Alcott in his experimental

school in Concord, and Emerson in his philosophical lectures and

writings.

Emerson, born in 1803, grew up as the second of

five sons (two daughters and another son died in infancy) of a

Unitarian minister William and his wife Rebecca. His father died when

he was almost eight and he was raised by a circle of women, including

an aunt with whom he would become very close. At age fourteen he

entered Harvard College and graduated at age eighteen (surprisingly,

only in the middle ranking of his class). He went to work with a

brother, William, teaching young women at his mother's home. When

William went off to Germany to study divinity, Emerson then established

his own school. Several years later he himself entered Harvard Divinity

School for study. In early 1829 he was ordained to the ministry at

Boston's Second Church as its junior pastor.

Then tragedy began to hit Emerson. In 1831 his

young wife Ellen died of tuberculosis. Then a younger and very

brilliant brother, Edward, who also had long been struggling with his

health, both emotional and physical, died of the same disease in 1834.

Finally another younger brother, Charles, died in 1836, also of

tuberculosis. Emerson was devastated.

Following his wife's death, he began to distance himself emotionally

from traditional Christianity. The following year (1832) he resigned

his position at the church to begin the search elsewhere for the answer

to life's questions. At the end of that year he departed for a grand

tour of Europe, where he would meet a number of such intellectual

luminaries as the English philosopher John Stuart Mill and the Scottish

lecturer and social commentator Thomas Carlyle. In Paris he would

become intrigued by the botanical gardens of the Jardin des Plantes,

where he hit upon the thought of how all things in life seemed

mystically interconnected.

Returning to America in October of 1833 he

contemplated Carlyle's career as a lecturer, and the next month

undertook the first of the 1,500 lectures he would offer over the next

near-half century. These lectures would be his stock-in-trade, the

source of a number of books he would publish.

In 1835 he remarried (Lydia or Lidian) and they

moved to Concord, where two sons and two daughters were born. Here, in

company with three other scholars, the Transcendental Club was founded

(1836) – with the hope of birthing a community similar to the salons of

Europe where intellectuals would gather to discuss weighty matters of

life. Among those who would join them was Thoreau, for whom Emerson

took on something of a role as a father-figure.

Emerson's split with Christianity became evident

when in 1838 he delivered a lecture at Harvard Divinity School,

affirming that Biblical miracles and the claim of Jesus' divinity were

merely the inventions of the classic mind that assigned God-like

qualities to their heroes. Emerson instead advocated something of a

Humanism that freed the soul from the shackles of traditional religion

so that it could soar in search of the higher meaning of life. Harvard

Divinity School was scandalized by his bold Humanism (he would not be

invited again to lecture there, until thirty years later when even

Harvard Divinity School had begun to come around to holding many of

Emerson's Humanist ideas).

Efforts were made by Emerson's neighbor Alcott to

put their organic philosophy into full operation as an experiment in

communal living, when the entirely vegetarian farm Fruitlands was

established. It was not a grand success. After it failed, Emerson

purchased another farm for Alcott for a second attempt. He even

purchased two sections of land for himself (though he himself did not

work the land). As it turned out, the Transcendentalists were better at

thinking, discussing, lecturing and publishing than at securing

material success, although Emerson's lectures were beginning to pay

well and his books were being widely read.

Emerson now branched into esoteric or

Universalistic study, taking up the study of Hindu Vedanta, reading the

Bhagavad Gita and commentaries on the Vedas by Henry Thomas Colebrooke.

His philosophy of the Oneness of Life had the larger religious

confirmation of the Hindu religion. This fit his temperament better

than traditional Christianity.

The earthier intelligentsia

Meanwhile, for those less comfortable, where

life's dangers were not guaranteed to be manageable, where life could

suddenly take a violent turn (hunger, disease, Indian massacre) such

Humanist Rationality seemed as absurd as their personal trust in a God

of miracles seemed absurd to the Humanists.

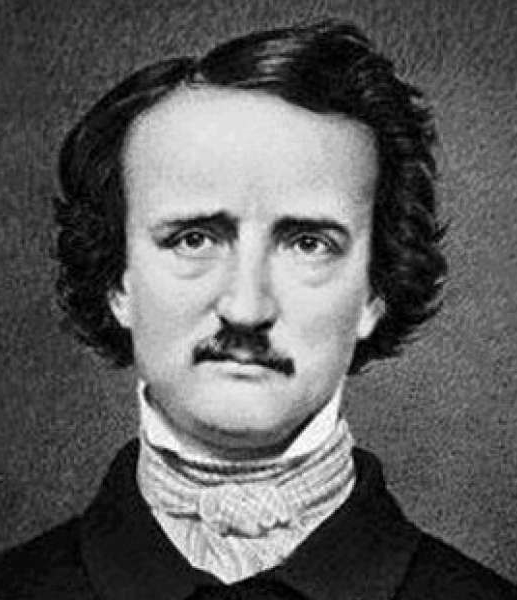

Indeed, even Nathaniel Hawthorne, who once was a

neighbor of the Concord Transcendentalists, eventually became something

of an anti-Transcendentalist, tending to delve more into the darkness

of the religious ethical issues of his era in his novels The Scarlet

Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851). Likewise, Edgar

Allan Poe could be just as abrasive in his dislike of the romantic

optimism of Transcendentalism.

There were also a number of other American writers

and artists who represented well the life of the common man, the serene

primitiveness of the American landscape and the exotic culture of the

Indians, giving excellent characterization of the democratic realities

of life in America. James Fenimore Cooper wrote elegantly of the

complexities of life in America in such novels as The Pioneers (1823)

and The Last of the Mohicans (1826). And in the field of graphic art,

the works of Thomas Cole and others of the Hudson River School were on

a parallel with the best of European landscape artists of the same era,

as were the works of George Bingham who, in addition to his beautiful

landscapes, portrayed insightfully democratic life in the Mississippi

and Missouri River valleys.

|

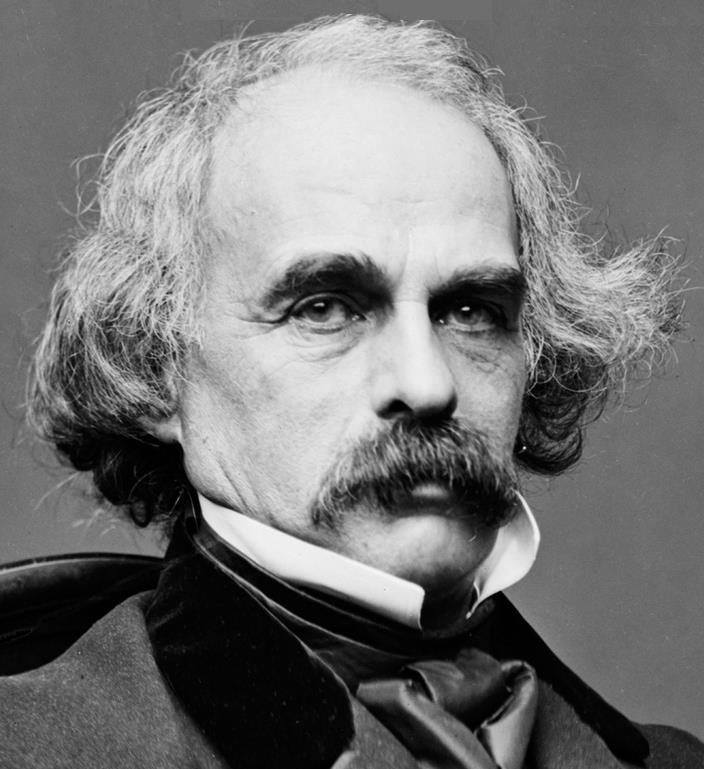

But

there were other intellectuals who saw life in darker colors

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Edgar Allan Poe

James Fenimore Cooper

THE

SECOND GREAT AWAKENING |

|

As far back as the 1790s, the first decade of the

new Republic, it appeared as if Christianity might be resolving itself

simply into a civic religion serving to provide a moral foundation and

discipline for the emerging United States as a distinct society.

Certainly that was how the intellectuals, especially the Deists among

them (most all intellectuals at that point), understood things. But

such civic religion did not fill churches, for it resided solely in the

independent thinking and behavior of citizens as they went about their

daily routines. It did not need pulpits to show the people how to go

about doing such things. Human logic itself seemed pretty good at

constructing such moral-intellectual systems.

Part of this developing religious dynamic

of Christianity as principally a civic religion was the result of the

way that the war and the consequent independence of American society

had a tremendous impact on the religious character of America. The

Church of England, well beloved by the Tories particularly numerous in

the American South, was devastated by the war. Eventually it was able

to service Anglican loyalists in America by establishing its own

Episcopal authority, and thus be able to carry on as before, but

independent of England itself in doing so.5

As for the Calvinist Congregationalists

in New England and Presbyterians in the Middle Colonies that had been

active in leading the independence movement, post-war America had been

expanding in population at a far greater rate than the slow process of

producing seminary-trained pastors could meet the demand for new

churches and individuals to pastor them. Also the very logical

character of Congregationalist and Presbyterian theology, especially

among the more highly educated of the membership (including,

importantly, pastors), caused many to be quite comfortable in the Deist

camp, leading some of them even to switch their loyalties to the

growing (for the time being anyway) Unitarian movement.

Baptists and Methodists however did not

have this same problem, being open to the recruiting of lay pastors

(not seminary trained but simply called out of general society to

Christian ministry). These individuals had been led to take up their

calls not by academic logic, but by a highly personal, and most

frequently highly emotional, sense of personal judgment, moral

cleansing and new purpose to their lives, a purpose calling them into

full service to the very process that had personally saved them out of

a world of sin. They were on fire to bring others to this same

spiritual renewal or revival that they themselves had gone through

personally. And they were willing to face all sorts of obstacles, both

by nature and by man, in order to bring (especially to the frontier

where churches were virtually non-existent) the gospel of salvation in

Jesus Christ to hungry hearts there. This was not mere civic religion.

This was religion of a very personal spiritual nature.

Millennialism6 and perfectionism

Behind all this religious activity was

something very much part of the spirit of the Jacksonian times. As

Tocqueville had noticed, Americans had a strong sense of personal

destiny, an urgency to accomplish some greater work, to move forward,

to fulfill some nobler purpose in life. Life was viewed as a challenge,

one faced with many obstacles, many of them deficiencies in the people

themselves, personal deficiencies or sins that needed cleansing, ones

that required some act of purification which would clear the way for

them to gain some personal victory. Christian revivals offered exactly

just such an opportunity for getting things right with God.

Empowering this activity was an abiding

sense that history was about to find completion in the form of the

second coming of Christ and his final judgment of all people, saints

and sinners, a widespread sentiment of the times due in part to the

horrible 1837–1841 Depression which undercut severely the American

belief that life moved forward along largely logical lines. Surely this

grand catastrophe pointed to the ultimate and thus final judgment of

God in the form of the long-awaited coming of Christ as the ultimate

judge of life on earth.

Consequently, many Americans came easily

to the conclusion that they were approaching the millennium described

in Scripture (Revelation) in which all must be made perfect in

preparation for that final coming of Christ. Sinful behavior needed to

be corrected, both for society as well as the individual. Perfectionism

or social reform was thus urgent. The institution of slavery in

particular needed to be abolished – immediately. Alcoholism, which was

rampant on the Frontier and in the workshops back East, also needed to

be curbed. Caring for the poor became a priority. Injustices of

whatever variety needed to be addressed, the treatment of women being

one of the issues taken up by a new generation of feminists. Social

experiments accompanied this mood, in which varieties of utopian

programs were put in place to answer the challenge of the times. Most

of these failed miserably, but failure did not seem to discourage

others from trying.

Sadly, the quest for perfection usually

set one group against another, even splitting groups time and again as

perfectionists understood faults in the others, even small faults, to

be the work of the devil in his attempt to stop the arrival of the

millennium. It got confusing, and at times it became very bizarre in

the routes such perfectionism took this rather primitive religious

instinct so endearing to the American frontiersmen. But it made those

simple souls, those who had moved to the frontier because their lives

back East amounted to so little, now understand how special they were,

even how royal they were, their purity of conscience bringing them into

a very special relationship with God. On this sentiment they were very

ready to build a new world.

5In

the years between the 1st Great Awakening and America's war for

independence, the Church of England's Society for the Propagation of

the Gospel not only sought to bring the unchurched of America to

Christ, but more importantly, it set out to bring non-Anglican

Christians to leave their Congregational, Presbyterian, Quaker churches

and join the Church of England, being far more active in setting up

Anglican churches in coastal New England and the Middle Colonies than

along the American frontier. As we have already noted, this assault on

highly independent American Protestantism was another one of the ways

that England had infuriated the colonies and driven them to want full

independence from the mother country!

6A

belief that the coming of Christ will usher in a 1,000-year Golden Age,

a long period of time prior to the Day of Judgment, and the

establishment of a New Heaven and a New Earth.

|

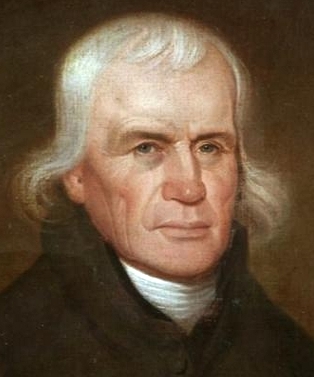

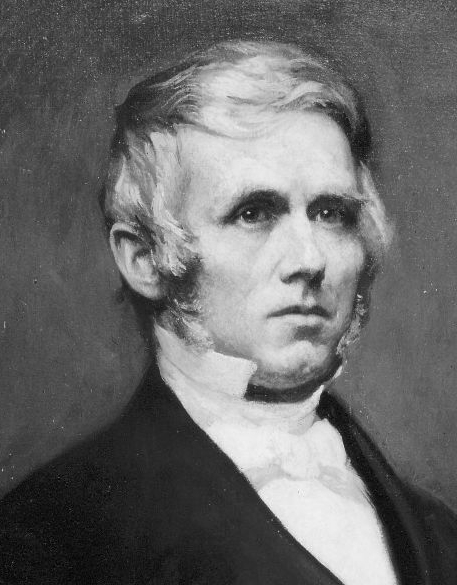

Francis Asbury

Highly empowered by this national mood was the

rising body of Methodists. Earlier, Methodism's actual founder, John

Wesley, had originally been very opposed to the American rebellion

against English royal authority. Consequently almost all of the

preachers Wesley had sent to the colonies returned to England when the

war first broke out. But Francis Asbury stayed behind, to organize

Methodist lay preachers to help nurture American hearts during the dark

days of the war. After the war, Wesley agreed to ordain American

Methodist pastors – including Asbury, whom he named as one of his two

Methodist superintendents in America, authorized to supervise those

pastors – in order to bring the Methodists into some kind of proper or

apostolic communion with the English Methodists. Thus it was Asbury and

his lay preachers in America who would push Methodism forward,

preachers who fit more closely the democratic mood of the times, able

to relate better to life on the frontier. Estimates are that Asbury

himself, in order to preach on virtually a daily basis, traveled

thousands of unimaginably horrible miles each year in hunger, cold, wet

or heat, frequent loneliness and extreme exhaustion, for a possible

total as much as 275,000 miles in order to deliver a total of 16,000

sermons! During his time of leadership (1784–1816) the Methodists grew

in number from 1,200 to 214,000 members, with 700 ordained preachers to

pastor the flock. Highly empowered by this national mood was the

rising body of Methodists. Earlier, Methodism's actual founder, John

Wesley, had originally been very opposed to the American rebellion

against English royal authority. Consequently almost all of the

preachers Wesley had sent to the colonies returned to England when the

war first broke out. But Francis Asbury stayed behind, to organize

Methodist lay preachers to help nurture American hearts during the dark

days of the war. After the war, Wesley agreed to ordain American

Methodist pastors – including Asbury, whom he named as one of his two

Methodist superintendents in America, authorized to supervise those

pastors – in order to bring the Methodists into some kind of proper or

apostolic communion with the English Methodists. Thus it was Asbury and

his lay preachers in America who would push Methodism forward,

preachers who fit more closely the democratic mood of the times, able

to relate better to life on the frontier. Estimates are that Asbury

himself, in order to preach on virtually a daily basis, traveled

thousands of unimaginably horrible miles each year in hunger, cold, wet

or heat, frequent loneliness and extreme exhaustion, for a possible

total as much as 275,000 miles in order to deliver a total of 16,000

sermons! During his time of leadership (1784–1816) the Methodists grew

in number from 1,200 to 214,000 members, with 700 ordained preachers to

pastor the flock.

The Methodist circuit riders

Also

playing a key role in this development were the Methodist circuit

riders, formed from that same adventurous spirit of the frontier

culture, who had answered a call from God to head out alone on

horseback into the Western wilderness. Here they faced storms, hunger

and hostile Indians – to bring the comfort of the Christian religion to

scattered settlements and cabins that dotted the wilderness. Their

offerings were not just the assurance that God was with these settlers

but that they were also somehow still connected with the rest of

society, which was also with them. The way the circuit riders helped

settlers to keep body and soul together was thus enormously appreciated

on the Western frontier, where the Methodist church – or at least the

Methodist movement – grew rapidly, soon to become the largest of the

Christian denominations in America. By 1840 some 3,500 circuit riders

and some nearly 6,000 pastors were supporting the faith of 750,000

Methodists!

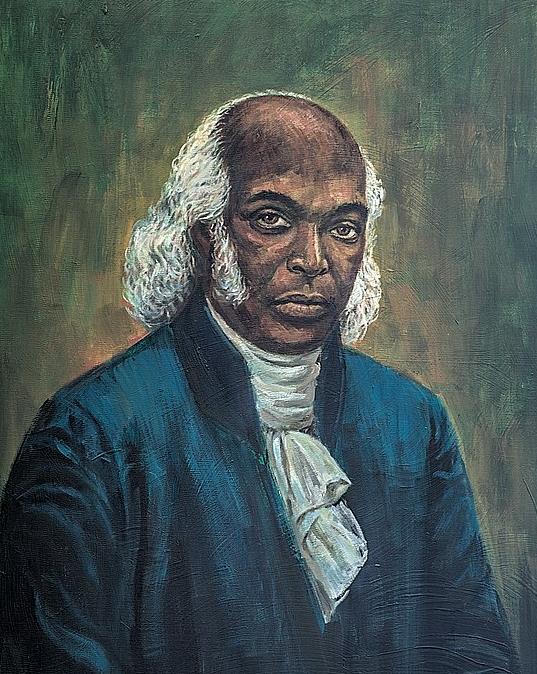

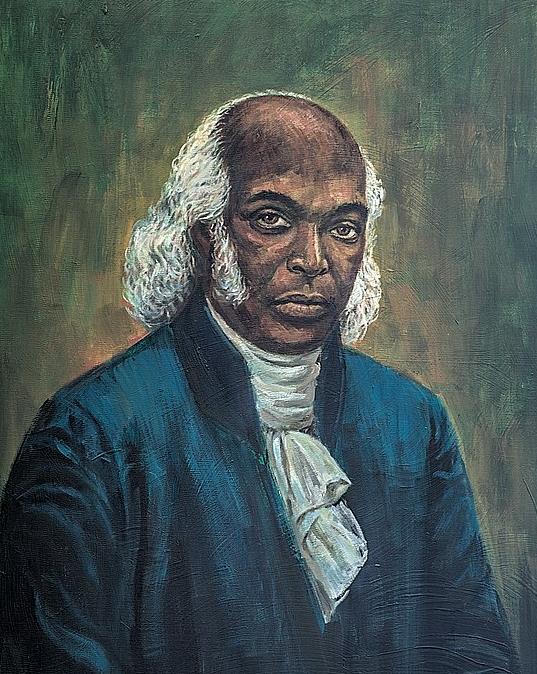

The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and AME Zion churches

The Methodists were officially opposed to

slavery from the beginning of the denomination's entry onto the America

scene in the 1760s. Asbury was hotly opposed to the practice, but

learned that to reach Black audiences held in bondage as well as

Whites, he would have to tone down his rhetoric on the subject.

Otherwise he would send slaveholders off into fellowship with Baptists

and Presbyterians, which at the time took no such position on the

subject. But the Methodist position did not go unnoticed by free

Blacks, and Methodism would have a tremendous impact in getting their

Christian world organized and up and running.

Richard Allen was a Black slave who was

able to work to pay for his freedom from his Philadelphia master. In

earlier years he had been very attentive to the Methodist circuit

riders who had come to his plantation, and even before securing his

freedom he had become active in encouraging fellow slaves with the

gospel message. Once free he continued this activity, forming one small

society and then another, until in 1816, in association with another

free Black pastor, Daniel Coker, five newly developed congregations in

Philadelphia were able to hold their first Methodist General

Conference. Taking up the spiritual disciplines of Wesley's Methodists,

they took the identity as the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church,

the beginning of what would eventually turn into another of one of

America's larger denominations.

Meanwhile in New York City in 1800

another group came together to form the Zion Church which grew

significantly, until in 1821 they were able to constitute themselves as

the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church under Bishop or

Superintendent James Varick. The AME Zion Church too spread across the

country among free Blacks. Both Methodist churches would compete in

eventually playing a leading role in shaping the religious lives of

newly freed slaves after the Civil War.

Richard Allen

James Varick

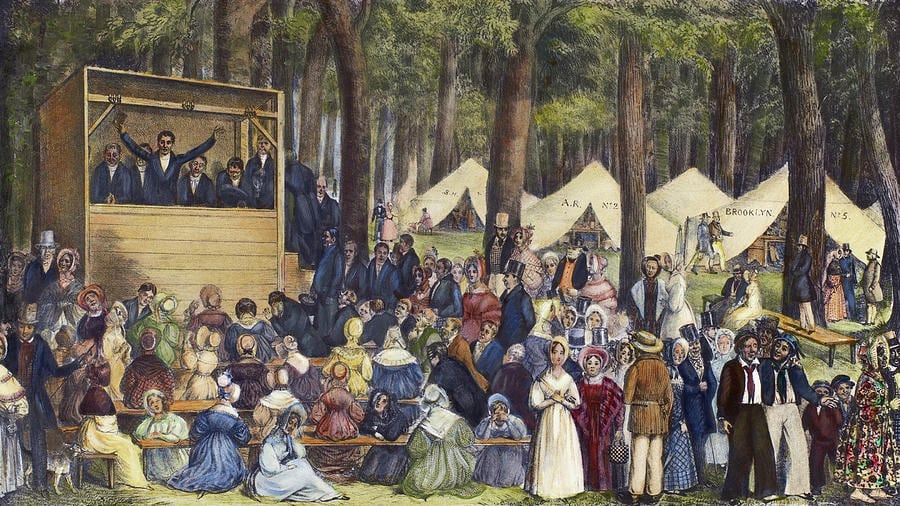

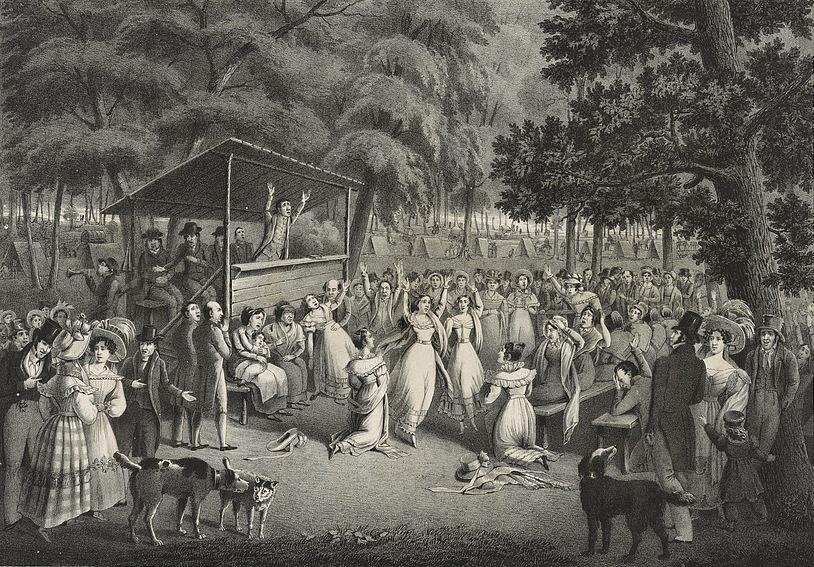

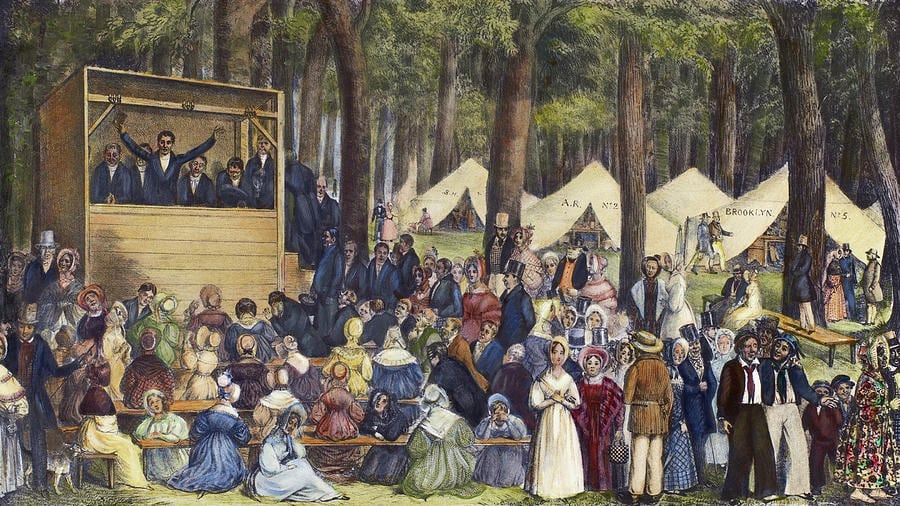

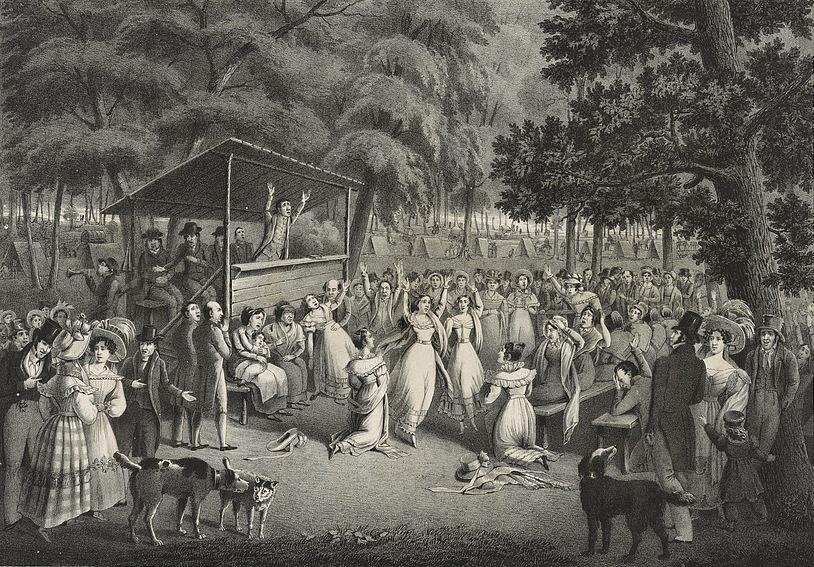

Camp meetings.

Meanwhile, off on the American frontier,

the highly individualistic but also highly isolated life on the part of

those Americans that lived well away from the comforts of the East

produced among Westerners a hunger for personal meaning within the

context of community, membership in larger society being a rare but

well-appreciated commodity. Most frequently this took the form of huge

gatherings whenever a local Christian revivalist appeared in the

region. Thousands would turn out to spend a week at an improvised

encampment listening to an array of preachers, singing and dancing,

shouting and fainting, and having a thoroughly good time.

|

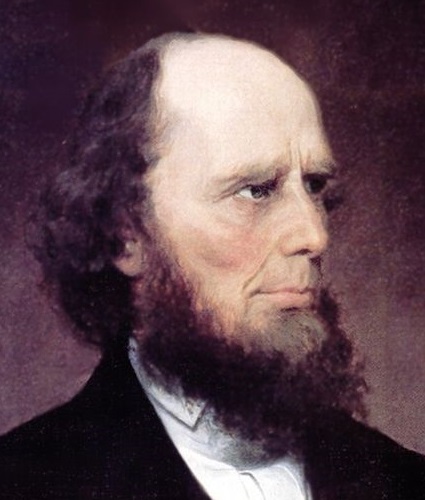

Charles Grandison Finney – Presbyterian revivalist

| In

a day of declining spirituality, Finney developed a highly organized

camp revival program which brought the gospel to the faithful in both

upstate New York (the "burned-over district" Finney termed it ...

because of the constant run of camp revivals there) and New York City. Others would copy his precise methodology.

|

|

Finney

Taking a more structured (and thus "logical")

approach to revivalism was the lawyer-turned-Presbyterian-minister

Charles Grandison Finney. Though a Presbyterian, a denomination which

traditionally viewed salvation as solely a matter of God's graceful

election (and thus not really a personal work or achievement of man

himself), Finney fit better the spirit of the Baptist and Methodist

revivalists. He was required to appear before a Presbyterian board to

examine his views on faith versus works, an issue which has caused considerable controversy since almost the founding of

Christianity. In the end he satisfied the board that he preached a

doctrine of grace rather than works, although his revivals' goal of

cultivating immediate repentance and renewal had something of the

quality of works before grace.7 His careful structuring of his

revivals, taking place in the period 1825 to 1835 in both the rural

setting of up-state New York and the urban setting of New York City,

became a model that other revivalists would follow. It helped not only

tone down (somewhat) the emotional level of these revivals, it also put

them on steadier religious foundations.

7But this is a subject that no Christian has ever satisfactorily resolved by mere logic or precise theological argument!

A Methodist camp meeting employing the Finney model

|

Millerites and the Seventh-Day Adventists

Another New York revivalist who played big on

these instincts was the farmer and Baptist lay-preacher William Miller,

who in 1833 predicted (on the basis of calculations he drew up from the

Book of Daniel) that the long-awaited event of Jesus Christ's return to

earth was going to take place sometime in the period 1843–1844, the

accompanying rapture also ending life on this planet. His views began

to gain wider acceptance as the 1840s loomed into view, his prophecy

even taken up by followers in England, Norway and Chile. Ultimately in

1844 he and his followers gathered on hilltops and rooftops in March,

again in April and finally in October in anticipation of the rapture.

But instead a Great Disappointment occurred when Jesus failed to show

up on schedule, causing his following to break up.

Surprisingly, however, this was not the

end of his massive religious movement. Others picked up Miller's vision

(particularly its millennialist perspective), importantly the female

prophet Ellen G. White, who cultivated a huge group of followers that

would eventually take the name Seventh-Day Adventists. They took up

perfectionist ways in the avoidance of alcohol, meat, and other foods,

advocating instead vegetarianism. From this group would eventually come

such famous breakfast food producers as Kellogg and Post.8

The Burned-over district9

One of the

places that seemed to be particularly active in this new religious

dynamic was the "burned-over district" of Western New York. Here wave

after wave of millennialist revivals occurred, producing some of the

most notable elements of the Second Great Awakening. The Millerites

were very numerous in this region. Shakers were also numerous in this

part of the state.10 The utopian Oneida Society was also established

there to practice the idea of social communalism.

8Vegetarianism was a common trend among the millennialists, who believed that meat-eating made man a brutal beast.

9The

term "burned-over district" was assigned by Finney to this region

because it had held so many revivals that Finney was certain that there

could be no one there left to convert.

10The

Shakers, as the Quakers before them, were noted for the shaking of

their bodies when they entered into a rapturous union with the Spirit

of God. They were notable also in that they believed that sex was

bestial behavior and thus they did not have offspring of their own,

forcing them to keep the community going through converts. Their

religion required all property to be held jointly; the equality of the

sexes; children (brought in from the outside world) belonging to the

whole community; the profits of workmanship shared communally, etc.

William Miller

Ellen G. White

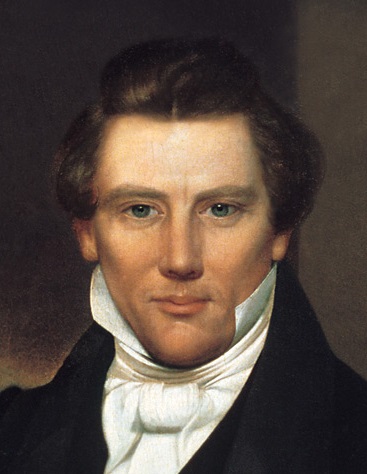

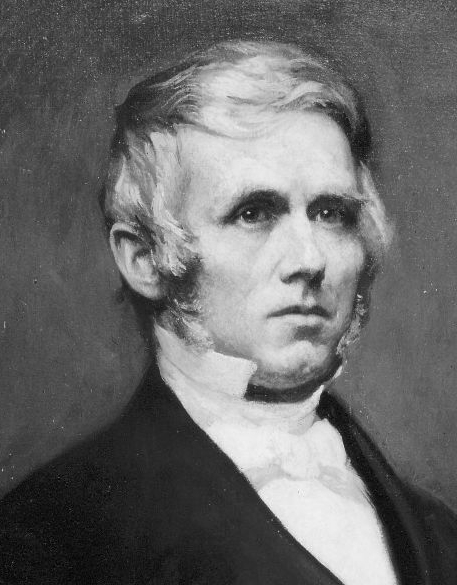

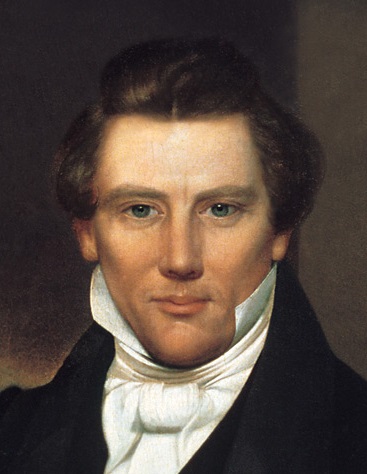

Joseph Smith

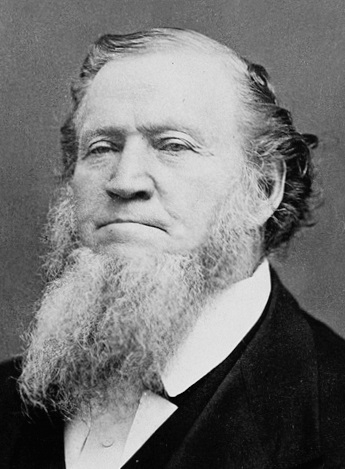

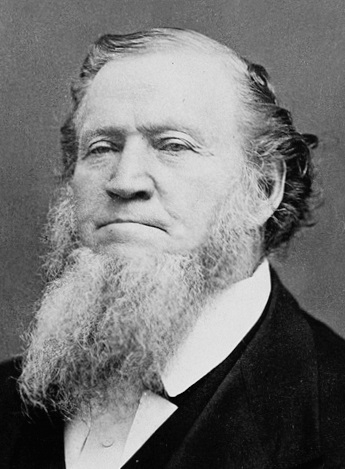

Brigham Young

|

The Mormons

Certainly the most amazing phenomenon to come out

of all this millennialism, and in this case even this same burned-over

district of Western New York, were the Latter-day Saints or Mormons, a

group that followed the prophecies and teachings of Joseph Smith, Jr.

As a teenager, Smith claimed that he had

a number of visions, the most important being a visit by the Angel

Moroni in 1827, who directed him to a place where he reportedly uncovered a book

of golden plates on which were written in some form of reformed

Egyptian the story of the ancient Jews and of Christ and his visit to

America. Using a special technique, he translated what he saw written

there by ancient authors (Mormon being chief among them), which in 1830

Smith published in English translation as the Book of Mormon.11

That same year he formed his first congregation as the Church of

Christ, teaching his followers the new doctrines, and then sending them

west to spread the new revelation as Latter-day Saints.

His ultimate goal was to establish a new

Zion, a community of the Latter-day Saints, to prepare the way for the

coming of Christ. At first he thought it would be in Ohio, where in

1831 a large group of his followers assembled. But then some of his

followers moved on to Missouri, planning to establish his New Jerusalem

or Zion there. But they ran into trouble when the local citizens

reacted to the Mormons pouring into their area. Smith ran into the

resistance of the local Missouri militia when he arrived in Missouri to

try to secure the land for his followers, and thus he decided to build

his temple in Ohio. But a major bank failure (resulting from the panic

of 1837) undermined the harmony of his followers and Smith migrated

with those who still remained with him back to Missouri. Once again he

faced stiff resistance there, except this time organized by the

governor of Missouri, who in 1838 was determined to drive the Mormons

from his state. Thus some eight thousand Mormons followed Smith to

Nauvoo, on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River.

For the next few years he was able to

proceed in the building of his temple, until the citizens of Illinois –

seeing the land being overrun by these Mormons and shocked at the

practice of polygamy taken up by Smith in 1843, a practice that seemed

now so central to Mormon social organization – thus also began to take

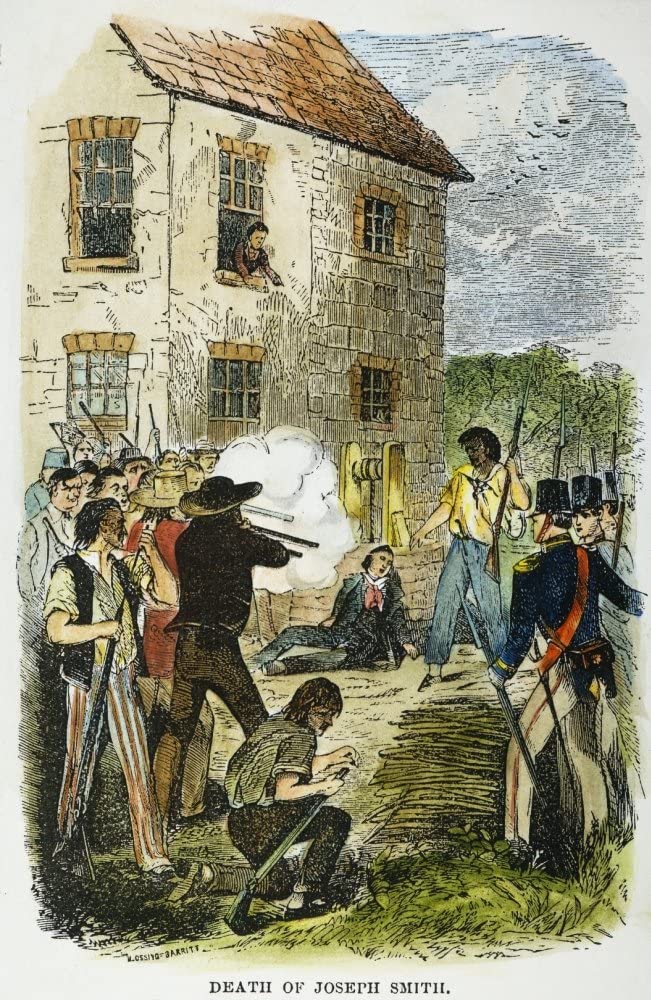

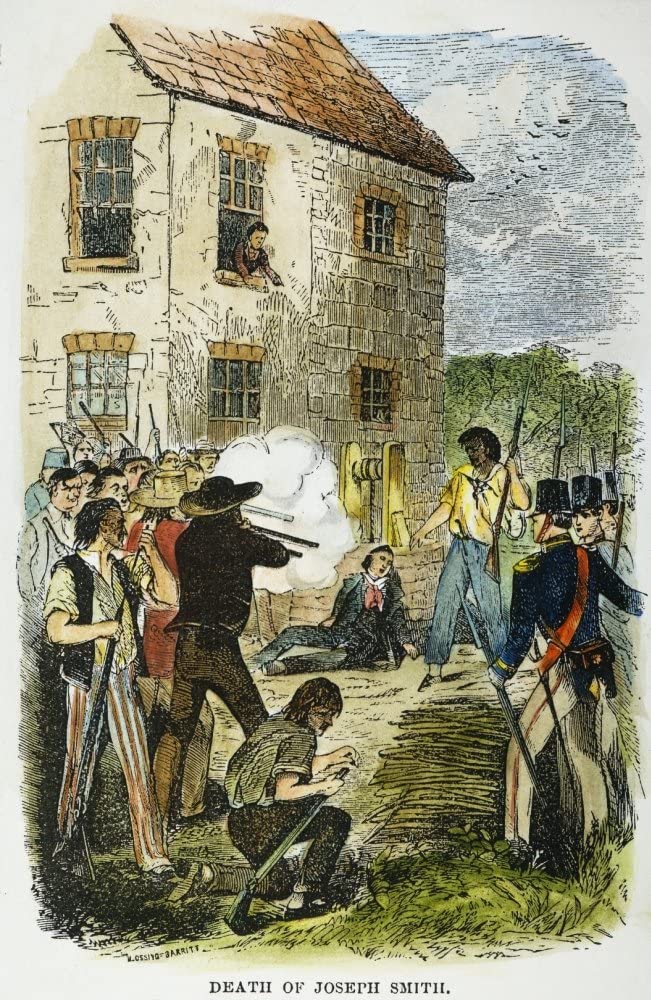

up arms against the Mormons. Then in June of 1844 Smith and his brother

Hyrum were killed by an angry mob, throwing the Mormon community into

confusion as to who was then to lead them.

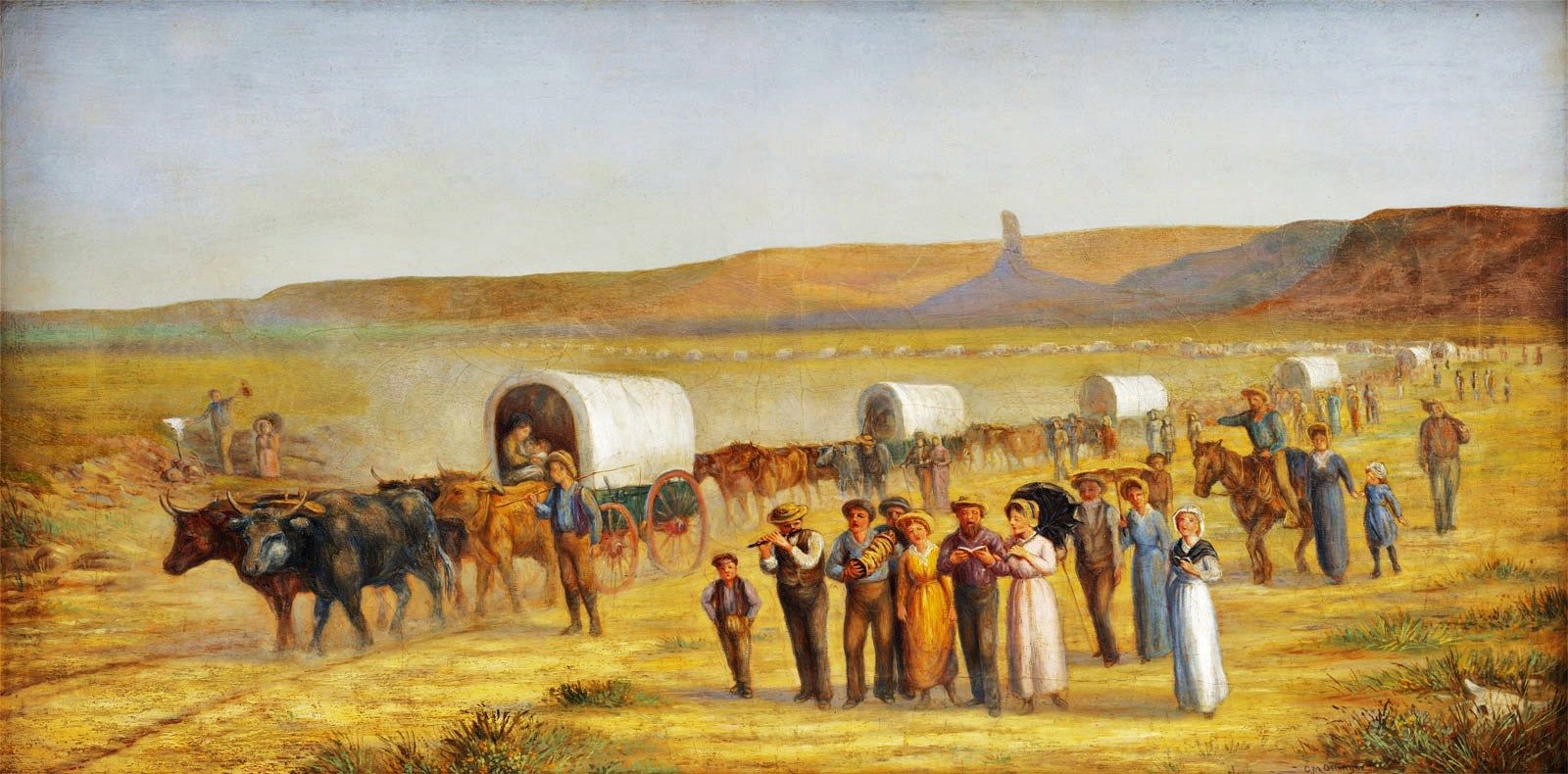

At this point a number of Smith's

colleagues stepped forward to claim succession. Brigham Young took the

lead, although other individuals also claimed the title and led their

followers off to form their own separate Mormon communities. But after

two years of trying to make things work out for them in Illinois, Young

decided in 1846 to take his thirty-five wives and hundreds of followers

West, all the way to the Utah territory in 1847 where they hoped to be

able to build their community in peace. There indeed they found just

such security – at least for a decade – and from there began to send

out missionaries to the larger world around them, to build the new

faith in anticipation of the coming millennium.

11The

book states that tribes of Israel (the Ten Lost Tribes?) had managed to

get themselves to the New World – as well as Jesus himself, who

appeared to the Indians soon after his Resurrection, producing several

centuries of exceptional peace among the Indians. Indeed, the book

claims that the Indians were in fact descendants of these migrating

Israelites.

Smith's Temple at Nauvoo, Illinois

Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum murdered by an angry mob of local citizens

(June 27, 1844)

Young leads the Mormons West from Illinois ... to Utah

THE LARGER CHRISTIAN MISSION |

|

New School versus Old School Christians

All of this highly emotional spiritual adventure

impacting the young Republic was having the effect of splitting the old

Calvinist religions (Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Dutch Reformed)

between two camps: the New School group, supporting the revivalist

trend, and the Old School group opposing it. Once again, similar to the

earlier Great Awakening of the 1740s, the highly emotional character of

these revivals seemed to Old School conservatives to be a most

undignified way to bring people to Christ and also very shallow in how

it might develop Christian life over the long-term in comparison to

well-thought-through traditional Christian understanding. Worse, New

School revivalism seemed to support the Arminian (or Methodist) idea

that man was somehow able on his own to rise above his state of moral

or self-focused depravity and elect or choose entirely on his own his

personal salvation. Also, of course, the very idea that a person was

not properly aligned with God without having one of these highly

emotional moments of conversion seemed highly offensive to those raised

since their youth to follow the lines of the faith as best as they

could, understanding that they were indeed sinners, but always

throughout their lives as faithful Christians sensitive to the need to

keep themselves open to the judgments of God. For this latter group of

Old School or Christian conservatives the suggestion that the path they

were on was not sufficient because it had never arrived at an emotional

crisis point of decision was outrageously ridiculous.

Christian mission societies

However, the

Second Great Awakening did not in fact somehow leave the Old School

churches out of the religious developments of the early 1800s. On the

contrary, there were some very significant developments that took place

among these older denominations. Although they did not take on the

colorful features of New School revivalism, they went a long way in

developing the religious character of the young Republic.

What is being described here is the birth

in the 1810s and 1820s of a large number of interdenominational

Christian societies that sought to set Christianity to the task of

taking on a number of social problems, blemishes that embarrassed good

Christians. These Old School Christians also believed strongly that

America had a vital role to play as a model of Christian virtue to the

larger world. These new societies were thus set up to provide Christian

demonstrations as to how such issues as poverty, illiteracy, and just

plain ignorance of the Christian gospel were to be taken on by the

faithful.

Working across denominational lines

(Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed,

etc.), Americans were very active in forming such groups as the

American Bible Society (to help every American family find itself in

possession of a Bible), the American Sunday School Union (to develop

Biblical literacy among the children of all social classes), the

American Tract Society (to put in the hands of everyone the simplest

explanation of and call to Christianity), the American Anti-Slavery

Society, and the American Temperance League (both fighting particular

social evils). Then there was the inter-faith (Congregational,

Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed) American Board of Commissioners for

Foreign Missions (ABDFM) created in 1810, which sent missionaries to

the Cherokee (and other American Indians) and ultimately overseas to

Hawaii, China, India, the Middle East and finally Africa. These

volunteer organizations became a vital part of the American

social-cultural dynamic that developed in accompaniment with America's

spread across the North American continent, and soon across the world.

Christian colleges

Christian colleges. As we have already

noted, from the time of the Puritans' early settlement in America,

higher education was a matter of vital necessity, not only in training

the pastors who would be expected to lead the Christian communities the

Puritans were establishing but in training in other areas such as the

law, business, finance, and teacher training – all so vital to the life

of their communities. Thus Christian America founded Harvard, Yale,

William and Mary, King's (Columbia), Georgetown, the College of New

Jersey (Princeton), New Brunswick and Andover Theological Seminaries,

as well as colleges such as Mount Holyoke, designed to give women the

same opportunity at a higher education. In fact, in the period between

the founding of the colonies and the mid–1800s, over 500 colleges were

founded by America's various denominations. This too was a key part of

Christian America's larger mission to be a Light to the Nations.

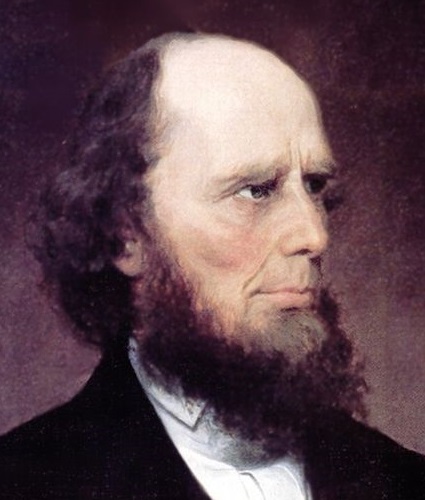

Horace Bushnell

And then there was the compelling voice

of a Connecticut pastor calling for interdenominational compromise, a

spirit of Christian unity ... and in doing so would greatly impact his

times (and continue to do so even through the rest of the 1800s): the

persuasive voice of Horace Bushnell. He took a unique position that

aligned him exactly with none of the contending Christian groups, yet

found value in all of them. With respect to the Old School Christians,

he was quite respectful of the way traditional Calvinist Christianity

was able to shape from a person's very early life, even childhood, key

Christian understandings that helped direct a person (elected purely by

the grace of God to the privilege of being born into full Christian

fellowship of Christian family and church) toward a long-term and

deeply faithful Christian life. This understanding was clearly laid out

in his very popular book, Christian Nurture

(1847). At the same time, he was highly supportive of the Unitarian

(and Arminian or Wesleyan or Methodist) viewpoint that man did have the

responsibility (and thus the choice in the matter) of disciplining or

ordering his own thoughts and actions as part of the mature Christian

life. And for a period of time he was quite supportive of the

Transcendentalists' mystical approach to God, seeing such a higher

reach of the soul as vital to a strong personal relationship with God.

However, in early 1848 he found himself decisively back in the support

of the idea of God, not in the form of the Transcendentalists'

Universalist Deity, but rather in the traditional Trinitarian view of

God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. But even in this retreat, he

continued to believe that although emotional revivalism was not

necessary for everyone to reach God, it certainly served very well

those who had become quite lost in their journey in life and was an

authentic way of bringing such lost but spiritually hungry souls to

Christ – provided that such revival always was followed up by on-going

fellowship with a worshiping community, in order to make the

salvation-event a lasting transformation.

Although he would draw criticism from all

the communities for his less than full embrace of their respective

positions, his ability to see Christianity above these divisions would

come to be of great value to American Christianity in the days ahead.

|

Horace Bushnell

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | | | | | | |

Inspired by a sermon preached in Baltimore in 1819

by Boston pastor

Inspired by a sermon preached in Baltimore in 1819

by Boston pastor

Right in line with this rising Humanist Idealism

were many experimental communities set out in America to show how a

perfectly designed social order could produce unprecedented prosperity

and happiness. One of the most active of such idealists was the

Scottish social philosopher, Robert Owen. He actually set up a number

of such utopian societies in America. But the most famous of these, the

one he put his heart and soul into, was his New Harmony community, set

out in the frontier land of Indiana. Owen bought the land in 1825 from

a community that had also, under the leadership of the Lutheran Pietist

George Rapp, attempted a similar experiment in perfect Christian

Socialist living, a Harmony project that failed because of the

inability of the German immigrants to live up to Rapp's great hope for

them.

Right in line with this rising Humanist Idealism

were many experimental communities set out in America to show how a

perfectly designed social order could produce unprecedented prosperity

and happiness. One of the most active of such idealists was the

Scottish social philosopher, Robert Owen. He actually set up a number

of such utopian societies in America. But the most famous of these, the

one he put his heart and soul into, was his New Harmony community, set

out in the frontier land of Indiana. Owen bought the land in 1825 from

a community that had also, under the leadership of the Lutheran Pietist

George Rapp, attempted a similar experiment in perfect Christian

Socialist living, a Harmony project that failed because of the

inability of the German immigrants to live up to Rapp's great hope for

them.