|

|

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

1381 John Wycliff is dismissed from Oxford University for translating the Bible into English A Peasants Revolt uses religious principles of Wycliff's followers, the "Lollards," as moral support for their rebellion ... turning the nobility against Wycliff and the Lollards 1409 The Council of Pisa tries to resolve a deep political split among several popes 1415 Czech reformer Jan Hus, who has followed Wycliff's example, is burned at the stake at the Council of Constance ... despite the Emperor's promise of protection 1431 The council of Basel (1431-1449) attempts compromise with the Hussites ... but is opposed strongly by Pope Eugenius 1494 Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola comes to power in the new Florentine republic ... also beginning religious reform there 1498 Savonarola and two other friar reformers are hanged and their bodies burned in Florence 1517 A disillusioned Augistinian friar Martin Luther posts his 95 thesis challenging the Church on a number of doctrines ... especially the sale of "indulgences" 1521 Luther comes (under Emperor Charles V's promise of protection) to the Council of Worms to explain his religious position refuge in the Wartburg castle of German Elector Frederick III of Saxony There he will translate the Bible into German 1522 Swiss priest Ulrich Zwigli urges that Scripture be the sole authority in the Church ... beginning the Swiss reform movement in Zurich ... supported by the local town council 1524 A Peasant's War (1524-1525) breaks out in Germany under the leadership of Thomas Müntzer ... German peasants calling for social-political reform 1525 Luther is shocked by such "radicalization" of his reforms ... and opposes the peasants 6,000 peasants lose their lives at the Battle of Frankenhausen Müntzer is captured and executed 1531 Zwingli dies from wounds received in a battle against pro-Catholic rural Swiss cantons ... but Zwinglian reform continues to grow in urban Switzerland under the leadership of Johannes Oecolampadius 1536 John Calvin writes (the first edition) of The Institutes of the Christian Religion ... to explain to French King Francis I why he should be supportive of the reform movement But Francis's issuing of the Edict of Coucy, forcing "heretics" to reconcile with the Church, convinces Calvin to leave France ... ending him up in Geneva, Switzerland 1537 Calvin and his associate William Farel are forced out of Geneva over a dispute about the exact character of the communion bread 1538 Calvin ends up in Strasbourg, leading a German congregation in reform 1540 Pope Paul III authorizes Ignatius of Loyola's Jesuit Order as papal missionaries ... and as rigorus teachers and defenders of the Catholic faith 1541 A hurting Geneva calls Calvin back to Geneva to contine his reforms there (1541-1564) 1543 Nicolas Copernicus (just shortly before his death) publishes a tradition-shaking observation (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) that makes astronomy easier to compute if the sun, not the earth, is employed as the center of the celestial system 1545 Pope Paul III convenes the Council of Trent (on and off between 1545 and 1563) ... to address the challenges presented by the Protestant reform movement 1546 Catholic priest John Knox joins a Swiss rebellion against Church authority in Scotland Knox is ultimately captured and forced to become a galley slave (1547-1549) 1553 Libertine Michael Servetus challenges Calvin's reforms ... at a time when such Libertinism was gathering some force in Geneva (and elsewhere) A strongly fought trial of Servetus results in his death ... being burned at the stake Bitterly pro-Catholic Mary I becomes English Queen (1553-1558) ... and begins a hunt for Protestant "heretics" 1554 After five years' exile in England, Knox heads to Geneva ... then returns to Scotland ... to undertake reform there 1555 The Libertines are defeated in Genevan elections ... putting Calvin in full power there 1556 Archbishop Cranmer is executed by Mary I ... despite his conservative policies Knox returns to Geneva to lead the English church there (1556-1559) 1559 Knox returns to Scotland to head up the "Presbyterian" Protestant reform of Scotland (1559-1572) |

|

|

A Sense of Growing Decadence in the Church

The profound corruption of the church – from popes down to parish priests – was a source of major frustration to the faithful – who had a profound sense of God's judgment over His people, the Christian community. Judgment would fall on this New Israel as surely as it did the Old Israel. A Growth of Independent Personal Judgment

Combined with this sense of frustration with the church was a growing independent-mindedness on the part of a new Humanist intelligentsia. The Church no longer held a monopoly over the thinking of scholars and teachers. The new printing presses had put in their hands a wider range of reading that had ever been available previously. Some of it was pagan, most of it was Christian. But in any case it opened up a world that was not automatically sifted through the scrutiny of the religious hierarchy. Oddly, one of the most unsettling elements of this new literature were the Hebrew and Greek manuscripts of the Old and New Testaments that became widely available. The new Biblical scholarship that this engendered not only pointed out (minor) flaws in the Latin Vulgate – but gave the new scholars a sense of personal judgment superior to that of the official church. The age of the individual conscience was being born! The Cchurch could no longer expect automatically to command the thinking of its Christian subjects. Within the context of this independent and very critical mood – at least on the part of a new breed of Humanist scholars – "business-as-usual" on the part of the Church was bound to create a massive reaction. A Major Shift in the Traditional Political Order of Medieval Christendom

For centuries, the whole of the medieval Christian order had been a single piece – understood to be ordained and supported by the will of God. It was the widely understood principle that all the social orders, from kings and popes down to the vast multitudes of peasants, all had their respective "place" in that medieval political, economic, social, cultural, religious, spiritual order – such places determined by God's natural ordering of all people. A person was placed into that order by the logic of his or her birth – and that by the will of God. It was God that determined who would be born a king, who would be born a peasant. This being God's righteous decree, there was little further thought that could be given to a rearranging this larger medieval social or political order. True, kings and bishops, who both belonged to the upper aristocratic orders, had been battling among themselves since the 1100s for dominance over this larger medieval social order. But such disputes did not involve the masses of European peasant farmers. They simply awaited the outcome of such struggles to see how marriages, political alliances, wars would move them from the domain of one lord (priestly or princely) to another. They themselves had no say in such matters. Their job was to till the soil and pay the lord their feudal dues. They always prayed that God would set over them a fair or just lord. But they themselves had no voice in the matter of who ruled over the land that they worked with their labors. The Rising Urban Power Base of the Renaissance

However the rise during the 1300s and 1400s of European commercial wealth – in competition with the traditional wealth of rural landholdings – was bound to upset this arrangement. Bankers, merchants, industrialists – who congregated along key trade centers – did not fit easily into this older social order. Though certainly their guilds and unions attempted to formalize their wealth, in fact their wealth was dynamic and always subject to a rapid shift in fortunes. The success of their labors was related to the wisdom of investment decisions that they made. To prosper, they needed a free hand – and a mind open to new and ever changing opportunities. During the 1400s this group sat uneasily under the traditional rule of medieval Church and Crown. Medieval feudal dues in the form of agricultural and military service owed the lord were cumbersome and at times counterproductive to the larger success of this new urban entrepreneurial class. It was inevitable that these towns would become centers of resistance against the medieval land-based social system. Indeed, in case after case these rising towns and cities were able to receive from the traditional local princely or priestly lord new charters which granted them (that is, the commercial elite or oligarchy that ran these towns) a tremendous degree of self-goverment – in exchange for the payment of taxes in currency. This was because money was becoming more important than land in undergirding the military might of a local ruler--and the princely and priestly rulers in fact preferred monetary payments over land service from their vassals. While land assessments and service obligations might feed their courts and fill their armies with men-at-arms – only money could buy them the new luxuries – and the new military technologies – that traditional land-based service could not. Reconstructing a Moral-Legal Order around This Newly Rising Order

But the independence of these towns – in keeping with their real power – did not provide the air of legitimacy that they needed to feel secure in their liberties within the newly rising order. At any time these urban charters might be revoked by the local prince or bishop by any whim or fancy (or suspicion). There really was no "right" of their own that the towns could hold up to these lords in order to demand equitable treatment. At least not until the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s gave them the sense that they had the right to accept or reject political authority in accordance with what their own consciences dictated. There was no power on earth, only God alone, who had the right to judge them in the matters of conscience, even political conscience. |

|

| Actually,

religious reformist urges reached all the way back to the 1200s and

1300s over a growing concern about the moral corruption rising

within the Church ... and a similar desire to return the Church

to its earlier, pre-Constantine ways – where the believer stood

directly before God in faith and not just through the priestly

ministrations of an institutional Church. John Wycliff (1320-1384) and the Lollards

In

1370s England John Wycliff got himself in trouble teaching just such

ideas. He also attacked a multitude of practices and features of the

church – especially the way it accumulated for itself enormous wealth …

at a time when so many of the faithful lived in deep poverty. And

he succeeded in offending the Church hierarchy by having Scripture

translated into English so that individual believers might come to

Godly knowledge on their own. He consequently was dismissed from

Oxford University in 1381 for his actions. But his ideas would

live on after him … picked up by the later reformers of the 1500s.Wycliffe's followers, contemptuously called "Lollards," from a Dutch word of derision meaning "mumblers" (originally directed at the Beguines), preached church reform in England. At first they were protected by some of the English nobility … basically as an excuse to bring some of the Church's vast wealth to their own hands. But then when a Peasants' Revolt broke out in 1381 (mostly due to the huge social stress caused by the Black Death and the ongoing Hundred Years' War) – the rebels justifying their actions employing Lollard themes – the nobility turned against Lollard leadership … despite the fact that the Lollard leaders themselves were no supporters of the rebellion. Wycliffe's Lollard movement was thus suppressed. But so was the intellectual ferment of Oxford university where his teachings had been widely accepted. |

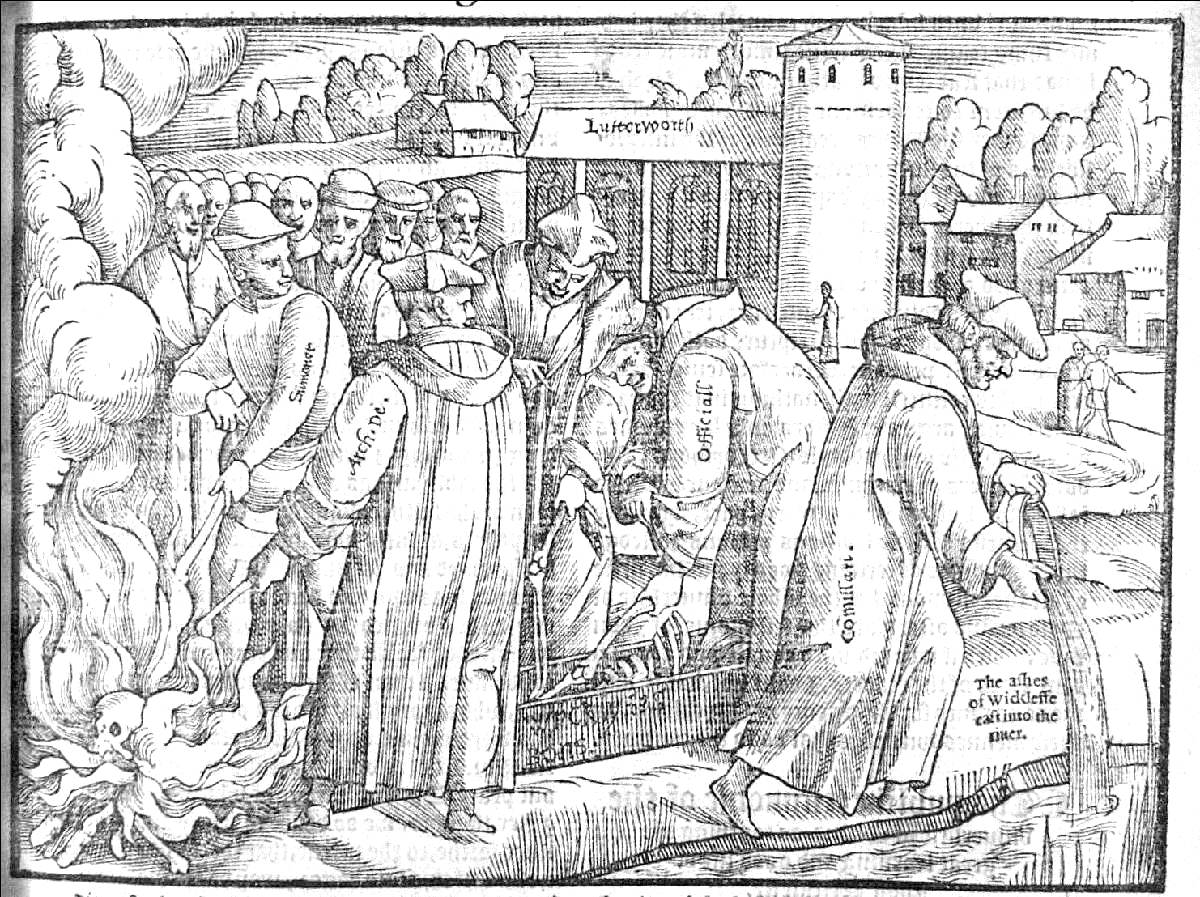

The burning of Wycliffe's bones, from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563)

|

The Reform Councils and the Council of Pisa (1409)

The Conciliar Movement. Also, the political turmoil of the Papal Schism pointed to the obvious need at the turn into the 1400s to get the Church to drop its political programs and get back to its major spiritual duties. Thus various Church councils were called (the Conciliar Movement) to unify and reform the Church – and at the same time bring independent voices of reform under submission. But church politics was not going to be easily put aside ... if at all. For a time it appeared that the various church councils held in the early 1400s might take precedence over the authority of the Pope. But ultimately the Conciliar Movement died on the basis of its own politics. The Council of Pisa (1409). This key council, in order to end the embarrassment of having two contending popes claiming to be the sole head of the Catholic church, deposed the two contenders, Gregory XII and Benedict XIII. This reform was undertaken even by the cardinals of both popes – who then elected a new pope, Alexander V. But when the two popes refused to step down, there were then three contending popes! Jan Hus (1374-1415)

Caught in this firestorm was the Bohemian or Czech reformer Jan Hus ... who took up Wycliff's cause at the University of Prague. Hus translated Wycliff's works into Czech and gave life to the reform ideals to the people. This stirred fear in the hearts of church officialdom. The Czech reform led by Hus was geographically closer to the Imperial powerbase of the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor (based in nearby Austria) … and thus less able to be conducted fairly quietly. Thus in 1414 Hus was called (under the Emperor's promise of safe conduct) to the Council of Constance to explain himself. But treacherously, he was arrested for "heresy" by the Council ... and burned at the stake in 1415. This was clearly intended to be an object lesson to those who had similar ideas of shaking up the Mother Church with their unwanted ideas of ecclesiastic reform. But instead, this display of Church "discipline" merely sparked deep anger over Hus's treatment ... which in turn led to widespread revolt in Bohemia. At first, attempts to put down what had become a popular national revolt failed. Finally a compromise of sorts was reached with the Hussites. |

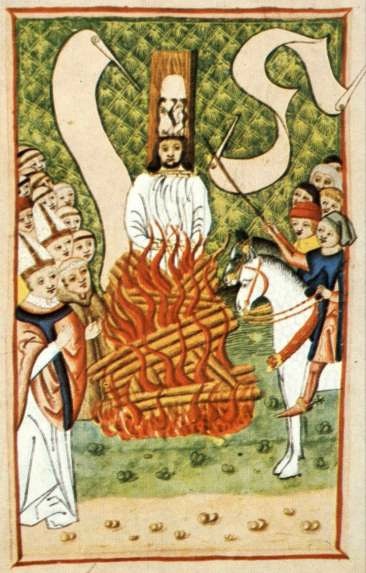

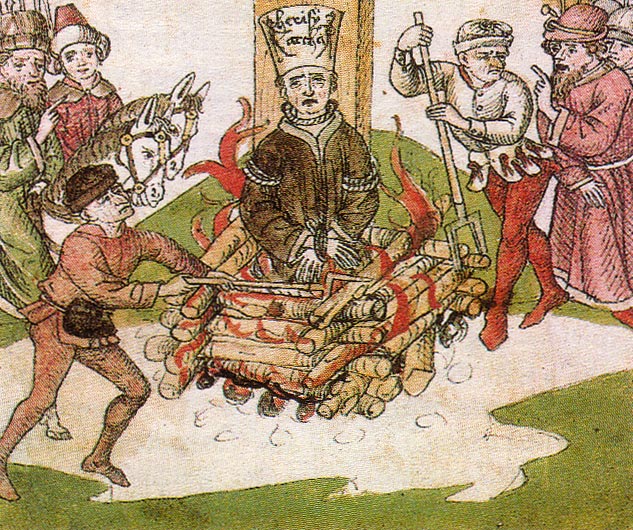

Jan Hus burned at the stake

- 1415

Jan Hus burned at the

stake as a"heretic"

|

The

Council of Basel (1431-1449)

It was a council held at Basel that made the first steps of progress toward reconciliation with the Hussites. Then it went further in defying a papal order to move to Bologna, claiming superior authority to that of the pope (Eugenius IV: 1431-1447). But the Council's subsequent efforts at reform of the ecclesiastical hierarchy caused it to overstep its true power – and Eugenius used this to his own advantage. Also, the pressing problems of the Turks and the need for closer relations with the Eastern church provided the occasion for the pope to split the council's power – bringing a portion of the council to Ferrara while the remainder carried on in Basel. Then its decision in 1439 to elect a pope in opposition to Eugenius undermined most of the council's residual authority. In the meanwhile, the papacy in Rome emerged as an ever-stricter defender of its ecclesiastical authority. Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498)

Florence briefly (the 1490s) came under the direction of a religious reformer, the Dominican monk-preacher Fra Girolamo Savonarola … a very popular figure among the poorer classes of Florence and a thorn in the side of the Florentine aristocracy and the Roman church. His prophecies about a new age arising out of corruptions of the former age seemed validated when the French king invaded Italy and the Medici fled Florence, allowing Savonarola to establish something of a puritanical Republic in Florence in taking on a grand effort to clean up the morals of Florentine society and open Florentine government more widely to the people themselves. But his refusal to join Pope Alexander VI's Holy League (against the French) brought him deep trouble with the church hierarchy (the pope threatened to put all of Florence under a papal interdict) ... and gave a local religious rival the opportunity to challenge Savonarola's religious authority. In 1498, the Pope and his agents challenged Savonarola to a public test by fire – which Savonarola failed miserably. He thus confessed (under torture) to fraud, he lost his popular support at home, and he and two of his supporters were arrested, hanged and their bodies burned in Florence's public square. Again, this was supposed to provide an object lesson for those inclined to challenge the religious-political status quo of old Christendom. Nonetheless, much of his reform movement lived on in Florence among other followers. However, in 1512, the Medici – with papal support – were able to return to power in Florence ... and end the reform movement there. |

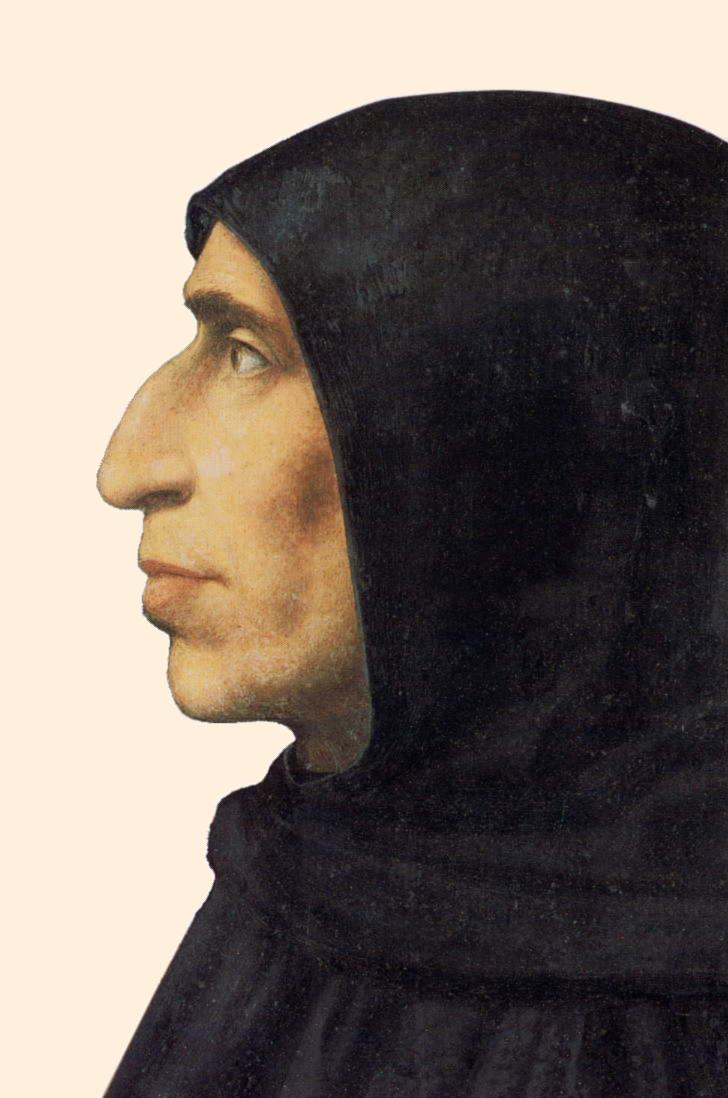

Florentine religious reformer

Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola –

by Fra Bartolomeo

(hanged and burned – May

1498)

Florence, Museo di San

Marco

The death of Savonarola (and followers) in Florence's central plaza - 1498

|

|

Martin Luther (1483-1546)

But

another monk, Martin Luther, was not so intimidated and threw a new

challenge of church reform in the face of the Pope ... and his close

associate, the "Defender of the Faith" Charles V of Habsburg – the

powerful Holy Roman Emperor (and also king of the dominant political

power of the day: Spain). Such a challenge was quite daring ...

if not even suicidal. But

another monk, Martin Luther, was not so intimidated and threw a new

challenge of church reform in the face of the Pope ... and his close

associate, the "Defender of the Faith" Charles V of Habsburg – the

powerful Holy Roman Emperor (and also king of the dominant political

power of the day: Spain). Such a challenge was quite daring ...

if not even suicidal.Behind Luther's defiant spirit was a long personal pilgrimage he had been on, one based on an deep desire to unburden himself of a profound sense of guilt and personal condemnation before God's judgment. For Luther, a personal breakthrough occurred as the message sank into the head of this Augustinian professor concerning Paul's teaching (Galatians and Romans) about divine Grace and forgiveness received through the simple faith of the believer – and not through the demands of any religious law or requirements of a religious system. So "liberated" was he that he felt that his discovery had to be brought to the world. Luther was a teacher of the Bible to his fellow Augustinian monks. His complete familiarity with Scripture made him aware of and angry about the huge disparities between the way the early Church and the contemporary Church functioned ... plus a much anticipated visit to Rome turned into a very disillusioning experience for Luther when he came face to face with the political intrigue and corruption going on in the holy city. Clearly the Church needed to clean up its act. Even Emperor Charles knew that. The popes had become famous for their corruption, epitomized at the beginning of the 1500s by the notorious Borgia family ... Father Rodrigo (Pope Alexander VI), his murderous condottiero son Cesare, and his beauty-queen daughter Lucrezia – among other illegitimate offspring ... not that a celibate pope was supposed to have children, much less mistresses! However, what finally sparked Luther's bold challenge to the Church was the sale of indulgences ... to finance the building of the pope's elaborate cathedral in Rome. This led Luther finally to post in late October of 1517 his 95 theses on the door of the Wittenberg castle church. It was time for the church hierarchy to answer for its actions and behavior. It was time for the church hierarchy to clean up its act! This action of Luther's seemed to be the signal for a number of German (and Scandinavian) princes to rise up in revolt against the political status quo of old Christendom defended largely by the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor. In Luther they saw their chance legitimately (i.e., on the basis of Christian morality) to break away from the monopoly of power held by Pope and Emperor ... and develop their own "Christian" sovereignty.1 Thus one of them, Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, took Luther under his protection just as the pope declared Luther a heretic and consequently to be denied all personal support and even to be eligible to be killed legally by anyone who encountered him. 1Also there was huge resentment in Germany for the heavy taxes imposed on the Germans in support of the Roman Curia ... and especially for the massive and very expensive cathedral being built in Rome with the goal of restoring the majesty of the papacy. |

Martin Luther - by Lucas Cranach

the Elder (1529)

Hessisches Landesmuseum

Darmstadt

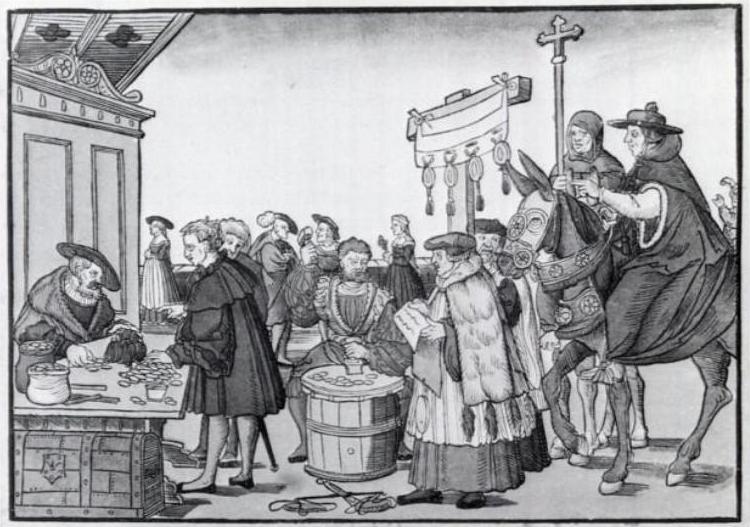

"A Question to a Mintmaker"

(the sale of indulgences) - Jörg Breu the Elder (c. 1530)

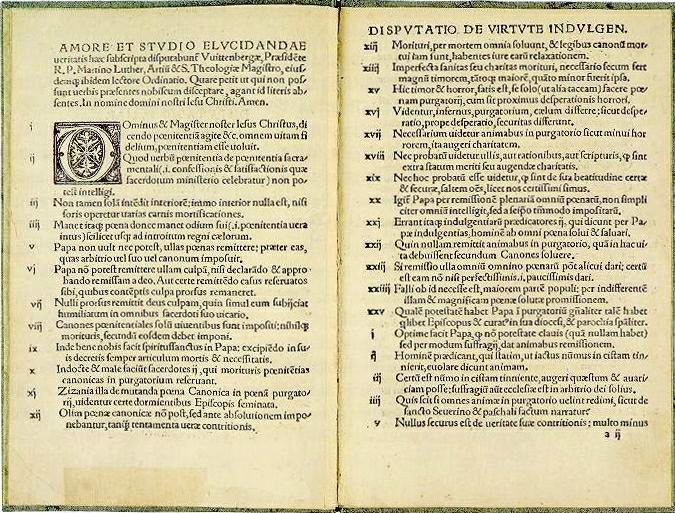

Disputatio pro declaratione

virtutis indulgentiarum (a printed copy of Luther's 95 Theses)

– Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter

d.J., 1522

Detail of Portrait of

Pope Leo X and Two Cardinals - by Rafael Sanzio (1518-1519)

Florence, Uffizi Gallery

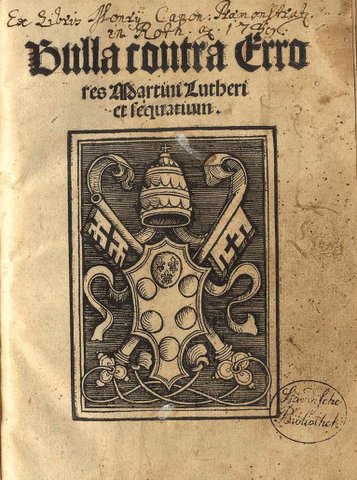

Title page of Pope Leo X's

Bull, Exurge Domine, threatening to excommunicate Martin Luther (1520)

Concordia Theological

Seminary

Wartburg Castle in Eisenach

-

where Frederick III, Elector

of Saxony, hid Luther away (1521-1522)

in order to keep him from falling

in papal or imperial hands

Luther's 1534

Bible

Luther's "Ein Feste Burg"

("A Mighty Fortress")

One of only very few early

printings of Luther's hymn. There are no known first edition printings

left.

This book is a second edition,

and extremely rare.

The Lutherhaus Museum - Wittenberg

|

Emperor Charles V tries to suppress Luther

The

newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V of Hababurg now took up the

issue on the side of the Roman church. Luther, now excommunicated but

still under the protection of Frederick and widely popular in Germany,

was called by the Emperor to an Imperial Council (Diet) at Worms in

1521 to give account of his views. Here Luther stood firm in his

views against the Roman church.And under an Imperial guarantee of his

freedom, Luther was able to get away from the Council before the

guarantee was retracted. From then on for the rest of his life, Luther remained in seclusion in Frederick's Wartburg Castle, translating the Bible into German ... and publishing numerous works denouncing in vivid language the leadership and practices of the Roman church. These writings spread rapidly (thanks in part to the new printing press) throughout Europe – until talk of Luther and his challenges to the Church (and thus Christendom) was under discussion everywhere. In the meanwhile the Emperor found himself preoccupied by an on-going war with France over control of various cities and principalities in Italy. Then the Turkish threat to the Emperor's Austrian holdings rose again. Thus the Emperor was seriously distracted in his effort to quiet Luther. Luther was relatively safe. |

Charles of Habsburg - Holy

Roman Emperor (Charles V) and King of Spain (Charles I)

by Rubens

|

The Peasant War of 1524-1525

But when German commoners took his challenges as an invitation to rise up against the burden of all of Christendom's traditional authority, civil as well as religious, Luther came out passionately against the revolt. Indeed, Luther was no revolutionary .. only a reformer. For Luther his call for religious reform was related to the matter of a sinner's personal justification before God. Luther showed little interest in making broader changes within Christianity beyond the throwing off of Roman spiritual authority – with its traditions of works-righteousness. Substantial changes in worship, for instance, were of lesser interest to Luther. Also the episcopal or hierarchical form of church government (rule "from above" by bishops) was not itself questioned by Luther – although he did strongly support the idea that the bishops were answerable to the local princes ... not to Rome. This it proved to be the case that he stood strongly on the side of the princes against the German rebels (Müntzer and the "Zwickau prophets") who took up the political cause of the German commoner against their rulers. In the course of this peasant rebellion, Luther came down harshly against the peasant rebels, denouncing them in the same strong language that he used to denounce the hierarchy of the Roman Church.2 The peasants and their leaders were put down cruelly by the local princes and their mercenary troops (6,000 peasants lost their lives alone in the one-day battle of Frankenhausen). The result of the Peasant War was to move real power over to the various German princes. Thus in Germany, the rule of the church was not a matter either of local congregational power – nor of the power of popes and bishops. Rather, it was the ruling prince in each of the many principalities that made up Germany who determined each in his own territory its particular Christian character. Some remained loyal to Rome (the southern German princes). Some followed the Lutheran line (the northern German princes) with their new Schmalkaldic League, a powerful political alliance which was dedicated, among other things, to backing Luther in every way possible. But in any case it was the local princes who made that determination. The dependence of church on state was thus set as the characteristic feature of German Christianity. Thus in the end, although he was willing to break from the feudal Church, Luther was not willing to break from the feudal civil government in Northern Germany. Consequently, Luther's reforms would go only part-way in bringing Germany out of its medieval background ... and leave it still with a feudal social system, one that would last all the way up into the early 20th century. Furthermore, because Luther's religious movement was constructed deeply on these social foundations of a rather permanently medieval (rural) north-central Europe, "Lutheranism" would have almost no impact on any of Europe's rapidly developing industrial (urban) areas. Thomas Müntzer (c. 1490-1525)

Müntzer was the active leader of the unsuccessful Peasants' Revolt in Thuringia (1524-1525) that so upset Luther. Müntzer took a mystical view about the humble classes being the true repository of God's Spirit and the proper instrument of God's transformative work on earth. His theological writings and personal leadership were of major importance in motivating the peasants' revolt against the German ruling classes. At the Battle of Frankenhausen in May of 1525 his peasant forces were defeated – and Müntzer was taken prisoner and executed. 2In his Wider die Mordischen und Reubischen Rotten der Bawren [Against the Robbing Murderous Hordes of Peasants] (1525) he advises the German princes to take necessary action against the peasants: "Let everyone who can, smite, slay and stab, secretly and publicly, . . . a poisonous, devilish rebel, like one must kill a rabid dog." |

The Battle of Frankenhausen - May 15, 1525

Thomas Müntzer - Leader

of the Peasant Rebellion

An 18th century engraving

by C. Van Sichem. No contemporary image of the reformer exists.

Andreas Bodenstein von

Karlstadt

A theological scholar who

supported deeper social-political reforms than Luther

|

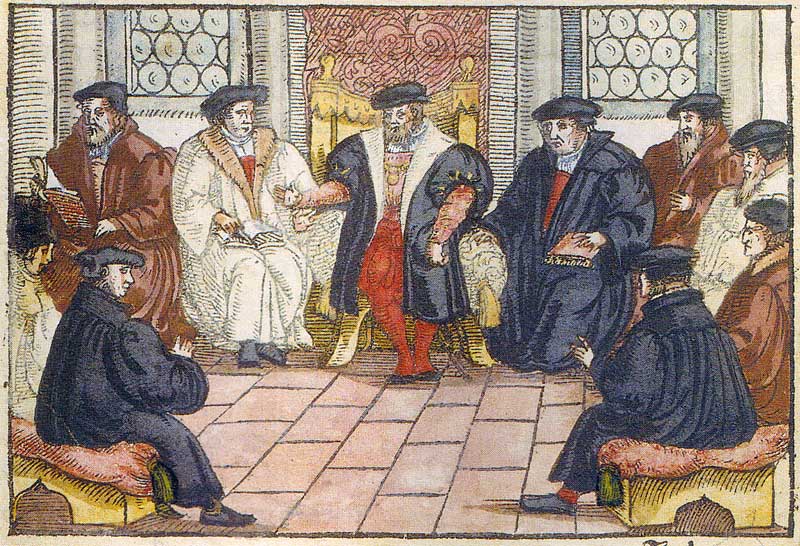

The Religious Colloquium

of Marburg of 1529 - anonymous - wood carving (1557)

By invitation

of the Landgrave

Philipp of Hesse, Luther and Zwingli came to Marburg

in September of

1529.

They were accompanied by

some of their followers, Melanchthon

being among these.

They were to settle their

dispute about communion.

But in this key matter they were not successful.

|

|

But it would be John Calvin in Geneva that would bring the Swiss Reform Movement to full power. Calvin was a Frenchman, schooled in the new humanist tradition … and prepared at the universities of Orléans and Bourges to be a lawyer. He fell in with a circle of French humanists who read with great interest the writings of Luther. Then, somewhere in the period 1532-1534 Calvin experienced a "sudden conversion" (the details of which unfortunately he never discussed publicly.) From this point on his well-organized mind was given over to theology rather than the law. At the same time his theological associations became very dangerous to an increasingly suspicious French king, Francis I. In 1536, Calvin felt compelled to write, with all respect to his monarch, a reply to Francis' suspicions about the "protestants": The Institutes of the Christian Religion.3 It was Calvin's hope that Francis, through this long essay, would come to understand that the protestants posed no threat to his rule – but only sought to revitalize the original Christian ideal on which the whole Christian realm ought to be properly based. Though it was the most compelling theological treatise explaining the protestant position – it did not have its intended effect of swaying the views of Francis. Instead, it identified Calvin as a voice of religious dissent, not tolerated in France. Calvin was thus forced to flee France. He intended to relocate to Strasbourg, where the reform movement was well underway. His path there took him to Geneva (Switzerland) ... where the Protestant reformer William Farel prevailed upon Calvin not to head on to Strasbourg but to stay in the city and help him strengthen the Swiss Reformed Movement which was growing rapidly there. Calvin agreed. But for Calvin, this proved to be a stormy decision. Geneva was an unruly city, and Calvin's natural bent toward orderliness and discipline quickly made him many enemies in the city. In the spring of 1538 Calvin and Farel were banished from Geneva. Calvin headed on to Strasbourg, where, by that time, the "Reformed" movement was well established. But in 1541, the old group of Calvin's supporters in Geneva urgently requested his return to the city. Calvin somewhat reluctantly decided to go back to Geneva – but on his terms. Upon his return, Calvin organized (accepting many compromises with the city Council) the religious life of the city around his new Ordinances – the foundation of Reformed polity. Geneva in turn became identified under Calvin's leadership as the model Christian city, the "New Jerusalem" of Protestantism. Calvin's reforms help develop a strong European "Middle Class"

Calvin was an urban European, steeped in the bourgeois mindset of the rising European urban "middle class." Calvin's interest in reform of the crumbling medieval moral legal order involved importantly a vision of the new urban order as central to a purified Christianity. Thus his interest in reform did not limit itself merely to matters of religious doctrine – as was the case for Luther. Calvin truly was interested in a comprehensive reordering of every aspect of post medieval life: political, economic, and social as well as theological. Importantly, he gave a theological rationale for the independent mindedness of the urban commercial class – arming them with Scriptural justification for going their own way within God's creation. Indeed, he encouraged them to establish purified political economic social orders as a way of purging Christendom of its corruption and of bringing glory to God in Jesus Christ. He made their soul searching independent mindedness a matter of the greatest importance in their standing before God. They not only had the right to be accountable to God alone as sovereign over them – they had the Christian duty to see that this was the case. The supposition was that any earthly lord who positioned himself between them and God was going to be problematic in their "purified" relationship with God and their covenantal life in the purified Christian commonwealth. Certainly the followers of Calvin attempted to convince the rich and powerful kings of Europe that their movement had no treasonous instincts – and that they planned to be good citizens in the realms where they lived. The kings were not convinced. And rightly so. Everything about Calvinism pointed to the idea of these people being accountable to no earthly ruler but to God alone. Switzerland, which was the birthplace of Calvin's Reformed Movement was well recognized for its independent-mindedness and refusal to acknowledge the rule of any princely lord over the land. No ... Calvin's Reformed Movement, or "Calvinism" was destined to bring a clash with traditional princely and priestly rulers who claimed to rule by "divine rights." That was exactly what the Calvinists claimed for their own "self-rule": the common people's own self-rule by divine right – even by divine imperative. There was no way these two mind-sets were going to work cooperatively. The extensive spread of Calvinism to urban Europe

It was not long before word spread widely of what was happening in Geneva under Calvin's reforms. Thus it was that during the second half of the 1500s, individuals from all corners of Europe came to Geneva to be a part of this new Reformed Movement. There they learned of ways to rebuild their communities as "covenant" communities … covenanted with God to live solely by Scriptural standards. And there in Geneva they busied themselves also in translating and publishing exactly those scriptural standards (the Bible) in the various languages spoken across the European continent. And thus it was that "Calvinism" came to be well-planted in the towns and cities of England (the Puritans), Scotland and Northern Ireland (the Presbyterians), Netherlands (the Dutch Reformed), France (the Huguenots), Western Germany, Bohemia and Hungary (the German, Czech and Hungarian Reformed Movement) – and even parts of Poland and Spain, where it later got eradicated by the Catholic Counter-Reformation overseen by the Catholic popes and Habsburg emperors. The Michael Servetus affair

Theologically, the times were very intense ... as we have just seen in Luther's reaction to the peasant revolt in Germany. But the intensity of the times does not offer much of an excuse as to Calvin's behavior in the face of a bitter theological attack on him (just words!) offered by a highly self-important Spanish intellectual (and accomplished medical doctor), who took delight in accusing Calvin of the evil of Trinitarianism, which – according to Servetus' book Errors of the Trinity (1531) – was nothing more than a grand deception of the devil ... and those who held to it, servants of the devil. Furthermore, Servetus presented himself (in his book The Restitution of Christianity) as the Michael of Scripture (from Revelation and Daniel) who was called to fight the antichrist, in order to usher in the End Times. Calvin got involved with Servetus back in 1546, when Servetus sent Calvin a copy of The Restitution of Christianity ... resulting in a correspondence between the two men which started out calmly enough, but which quickly grew increasingly bitter as accusations and counter-accusations intensified. Calvin thus stopped the correspondence ... totally embittered by Servetus. But Servetus went on, announcing abroad that not only was Calvin the imposter Simon Magus, but both Calvin and the Pope were antichrists, needing to be dismissed in order to restore Christianity to its original character. Servetus eventually got himself condemned by French authorities for his supposed Unitarianism ... escaped imprisonment, and decided to head to Italy for refuge. But strangely, he stopped by Geneva (1553) and decided to attend a worship service conducted by Calvin – when he was spotted and arrested. Servetus was duly tried and convicted of heresy ... and sentenced to be burned at the stake. Calvin tried to soften the sentence somewhat by calling for a beheading ... but could not get the Council to back down. Calvin and his friend Farel also visited Servetus in prison to get Servetus to recant of his Unitarian beliefs. But Servetus would not recant. And thus the sentence was carried out. To this day it is debated as to whether Calvin could not have exerted more pressure – for instance, to have Servetus banished rather than executed. But Calvin at the time was having his own political difficulties with the town council over matters of town governance governance … and seemingly needed to appear to be no less strong than the council in the (typical) handling of heretics. In any case, it is another example of how frequently Christian theological precision gets way ahead of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. And it certainly was not the first time, nor certainly also the last. In fact, in those days a lot of this sort of thing would be going on ... doing the West's Christian foundations a huge disservice ... not to mention a huge disservice to Jesus Christ. 3This work underwent numerous editions, increasing in coverage with each new issue, from a single volume of six chapters in 1536 ultimately by 1559 to four volumes of 80 chapters, indicative of his own development as a scholar-teacher. |

A young John Calvin - Flemish

school (Unknown) - (Oil on wood panel) 1500s

Société du Musée Historique

de la Réformation, Bibliothèque de Genève

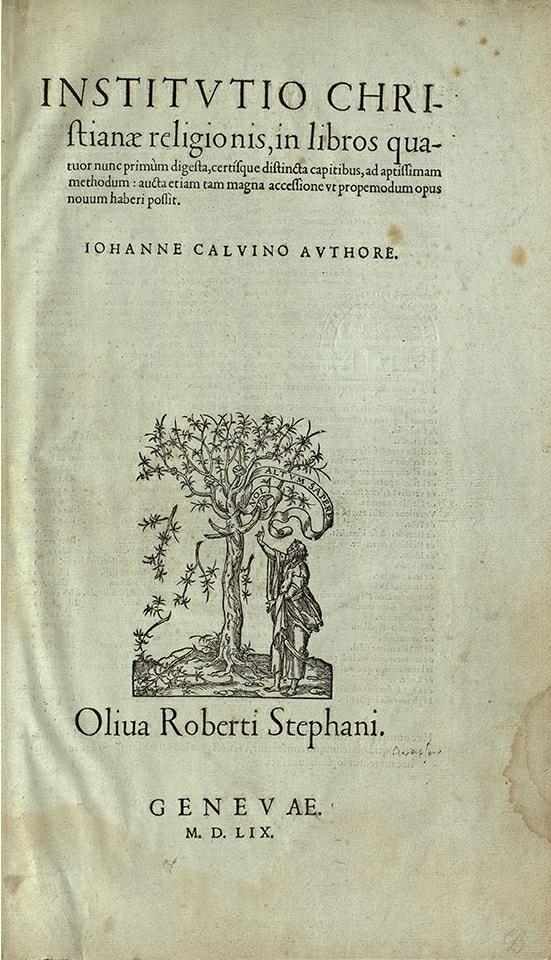

Institutio Christianae

religionis (Institutes of Christian religion). Geneva: Robert Estienne,

1559

This is the definitive and

fourth edition of Calvin's compendium of reformed theology;

the first edition

was published in 1536

Portrait of John Calvin -

anonymous - 1500s

Bibliothèque de

Genève

Portrait of John Calvin -

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) - 1500s

The Reformed Church of France,

Paris, France

Portrait of John Calvin at

fifty-three years old - 1562 - by René Boyvin

Bibliothèque de

Genève

Guillaume (William) Farel

(1580)

original portrait in Theodore

Beza's Icones

Unitarian Michael Servetus

(Miguel Servet) - by Christian Fritzsch

Spanish scientist and theologian

of the Renaissance. Burned at the stake in Geneva in 1553.

Martin Bucer (1560) - by

Jean Jacques Boissard

original in Icones quinquaginta

vivorum held in British Library, London

|

We

must at this point mention one of these "Calvinists": John Knox,

the great Protestant reformer of Scotland. Knox not only helped

direct Scotland to Calvinist Protestantism in the mid 1500s, but also

left a powerful political legacy within the Calvinist or Reformed

branch of Protestantism, a political legacy we call

"Presbyterianism." Knox's Presbyterianism not only deternimed the

organization of the Church of Scotland but also layed the foundations

for the growth of representative democracy in the American middle

colonies (from New Jersey to South Carolina) in the 1600s and 1700s. We

must at this point mention one of these "Calvinists": John Knox,

the great Protestant reformer of Scotland. Knox not only helped

direct Scotland to Calvinist Protestantism in the mid 1500s, but also

left a powerful political legacy within the Calvinist or Reformed

branch of Protestantism, a political legacy we call

"Presbyterianism." Knox's Presbyterianism not only deternimed the

organization of the Church of Scotland but also layed the foundations

for the growth of representative democracy in the American middle

colonies (from New Jersey to South Carolina) in the 1600s and 1700s.As with many Protestant reformers, Knox began as a Catholic priest, highly discontent with the moral and spiritual corruption that had overtaken the Mother Church. He was attracted to the Lutheran teachings of the early Scottish reformer, George Wishart; was appalled when in 1546 the Catholic cardinal had Wishart burned at the stake as a heretic; and then joined the group of rebels who moved to overthrow the hand of the Catholic church over Scotland. This put him in opposition to the pro-French party that ruled Scotland – and when French troops in 1547 crushed this Protestant rebellion in Scotland, Knox was led off to captivity as a French galley slave. His release was finally secured by the pro-Protestant English King Edward VI, leading Knox to come to England to be a Protestant pastor and then chaplain to the King But when Edward died in 1553 and Catholic Mary Tudor ("Bloody Mary") came to the throne, Knox left England and made his way eventually to Geneva Switzerland where he joined a community of English expatriates living and studying under the direction of the great Genevan reformer, John Calvin. Knox took a great liking to both Calvin and his teachings and subsequently became a major voice in the English/Scottish reform movement not only in Geneva, but through letters, to a growing Protestant movement back in Scotland. He returned briefly to Scotland in 1555, then back to Geneva to become pastor of the English church there ... and then finally in 1559 he returned definitively to Scotland to take over the spiritual leadership of the Protestant rebellion against the French-Catholic regent of Scotland, Mary of Guise. Seeing that things were not going well in Scotland for the Protestant party, Queen Elizabeth of England came to their aid against the French in Scotland. But when Mary of Guise died suddenly in 1560, the French Catholic cause in Scotland was dead. Scotland was now won for Protestantism. At this point Knox and his supporters began to reshape the Scottish church – not only theologically along the lines of Calvin's Reformed Faith born in Geneva, but also politically in a way that was Knox's special contribution to the Protestant cause. Knox took the idea of representative government characteristic of Calvin's reformed churches (communities lead by elected elders or "presbyters"), and applied it locally, regionally and nationally in total reversal of the top-down or hierarchical fashion of Catholic or "episcopalian" government. Thus local councils ("Presbyteries"), regional councils ("Synods") and national councils ("General Assemblies") that presided over the faithful were made up of representatives not of the political rulers over the church but of the people themselves. Thus was born "Presbyterian" or representative church government – the source of inspiration for the new Democratic or Republican forms of government that led eventually to the Constitution of 1789 underpinning the new American Republic. Despite success in the Protestant takeover of the church Scotland, the continuing existence of a Catholic monarchy in Scotland under Mary of Guise's daughter, Mary Queen of Scots, made life still highly problematic for Protestant Scotland – and for John Knox personally as the two locked wills in on-going battle. But eventually Mary's political blunders forced her to flee to England, where Elizabeth put her under house arrest ... and eventualy had her put to death. In any case Knox, worn out and sickly, died from his labors in 1572. But his work in Scotland was carried forth faithfully by others, notably Andrew Melville.  |

John Knox

Mary of Guise - Queen consort

of Scotland

mother of Mary I and regent

of Scotland - 1554-1560

(member of the House of

Guise, leaders of the fiercely anti-Protestant

Roman Catholic Party in

France)

Hatfield House

A young Mary I Stuart - Queen of

Scots - by school of François Clouet - 1560-1561

reigned 1554 - 1567 (forced to

abdicate in 1567 in favor of her

one-year-old son, James ... future King of both Scotland and England)

Hatfield House

|

| The

papal party finally realized the seriousness of the challenge to its

moral authority – and in 1546 called a Council at Trent to answer the

Protestant charges of ecclesiastical corruption and theological

deviation. Rigid discipline was re-imposed over the priests who

remained loyal to Rome. Luther's teaching on divine grace and

justification alone by faith was condemned. A campaign was readied to

wipe out any "heretics" not ready to return to Roman discipline. The

war was thus on. The Roman church, championed by the most powerful ruling family in Europe (the Spanish Habsburgs) – well-financed from their plunder of South and Central America – fought back cruelly, trying to stamp out the fires of the Protestant revolt. They succeeded in many places – and might have been fully successful had not the Muslim Turks attacked Vienna – the Eastern center of Habsburg power--during the height of this struggle. With the Habsburgs thus distracted, Protestantism dug in.

Pope Paul III and the Council of Trent

Pope Paul, under some considerable pressure by Spanish king Charles I, called the Council of Mantua (1537) to begin dealing with some of the issues of the reformation. But that Council got disrupted by a new round of warfare between Francis I of France and Charles. In 1542 Paul again called a Council, this time located at Trent (Austria) – thought it did not begin deliberations until the end of 1545. At the same time, Paul established the Supreme Tribunal of the Inquisition – a remake of the old Papal Inquisition which in the previous century had largely been suspended in its operations. The revival of the Inquisition in Spain under the Spanish monk Thomas de Torquemada – who for 18 years used its techniques of torture in a very "successful" manner against Muslims, Jews and Christian heretics – no doubt persuaded Paul of its constructive use in stamping out heresy. But political realities kept Paul's wonderful scheme limited to Italy – where it did a masterful job of discouraging Protestantism among the Italians (as the Spanish Inquisition did in Spain). Paul's Council of Trent continued its meetings after his death in 1549, though he had by then clearly laid out the lines it would take. The Council of Trent met until 1552 (though it had to move to Bologna from 1547 to 1551 to escape an epidemic). After 1552 it did not meet again until 1562 and completed its work the following year. At the Council (as in his life) Paul took a very reactive position in the matter of the need for reforming the church. To him it was a straightforward matter of organizing the powers of the church to stamp out the Protestant heresy. But Charles was deeply desirous of reform in the church in order to steal the ideological advantage the Protestants enjoyed over a number of issues dividing the church. Charles wanted the church to tighten up its moral laxness and make significant compromises in matters of doctrine pressed by the Protestants – in order to restore unity within Christendom. But Paul held the line against anything that looked like a concession to the Protestants. Thus the Council of Trent, under his leadership, moved to anathematize (condemn) the Protestant position and to reaffirm the church's position that Tradition stood as a coequal with Scripture in determining church issues and doctrines. The Latin Vulgate was pronounced the only authoritative version of the Bible. No translations into the languages of the day would be allowed. Further, no copies of even the Latin Vulgate were to be printed or distributed without authorization from church authorities. Also, the Council reaffirmed the doctrine that faith and works jointly formed the path to salvation – and not faith alone, which was a central Protestant position on the subject of salvation. Latin was to continue to be the language of the mass, the cup was to continue to be withheld from the laity during the sacrament of Holy communion, celibacy was to continue to be the order for the clergy – and a number of other doctrinal matters would remain unchanged. There were no doctrinal concessions to be made to the Protestants. However the Council did move to tighten moral discipline in the church – a major Catholic embarrassment in the dispute with the Protestants. Clerical appointments were to be scrutinized more closely for moral-spiritual justification. Education of the clergy was to be stressed. And the preaching skills of the clergy were to be improved. Overall, the tightening up of Catholic doctrine made the church look much less confused in the face of Protestant challenges. And the new moral regimen removed the matters that were the most obvious source of popular discontent against the church among the people (most doctrinal issues escaped popular understanding anyway). Indeed, Pope Paul and the Council of Trent gave the Catholic Church a new crusading spirit against the Protestant "heresy." |

Pope Paul III - who

convened the Council of Trent - painting by Titian

Naples, Galleria Nazionale

di Capodimonte

The Council of Trent - by

Cati da Iesi

(with allegorical figures

representing various virtues including "The Church Triumphant")

|

The Jesuits (Society of Jesus)

In 1540, Pope Paul III authorized Ignatius of Loyola and six companions to form a new priestly order, the Society of Jesus. Unsurprisingly, given Loyola's own background as a nobleman-soldier, the new order took on the character of a military unit, tightly disciplined to undertake very challenging work, as ordered by the Superior General (Ignatius initially) … himself under the personal command of the pope. They were to serve the papacy as frontline missionaries, "soldiers of God," taking Catholicism to all parts of the world – from Canada to Paraguay, to Ethiopia, to Japan, and everything in between! In Christian Europe itself, they would serve principally as teachers of classical theology, rhetoric, mathematics, even music! – most notably to the youth of Europe's ruling class. And as evangelists, they dedicated themselves to countering the evangelism being undertaken by the Protestants. |

The Founding of the Jesuits (Society of Jesus) by Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556)

- founder of the Jesuits - by Peter Paul Rubens (ealy 1600s)

Go on to the next section: The Development of the Dynastic State

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges