|

For centuries, the tale of this single event – the war between the Greeks and the Trojans – served as a social-religious explanation of life, its purpose, its powers, and its limitations.

The "judgment of Paris."

The war supposedly began as a result of a beauty contest among the

goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite ... with the unfortunate Prince

Paris of Troy as the judge. The other two goddesses were burned

when he awarded Aphrodite title as the most beautiful goddess ... and

Aphrodite "rewarded" Paris by having the exceedingly beautiful Helen,

wife of Spartan King Menelaus, fall in love with Paris.

The Achaean alliance.

When both Paris and Helen fled for Troy, King Agamemnon of Mycenae (and

brother of Menelaus) organized a huge Achaean Greek army and navy (some

100,000 men and over a thousand ships) and headed to Troy to try to get

Helen back.

Leading

soldiers of the Achaean army were Achilles – the greatest of all Greek

warriors – and Odysseus the adventurer ... and on the Trojan side,

Hector, son of the Trojan king and kindly hero but also a very

courageous and capable military leader.

The intervention of the gods.

But in any case it would be more than human dynamics that would

determine the outcome ... for the Olympian gods themselves became very

involved in the events, some supporting the Achaeans, others the

Trojans. Deception was often the tool used by the gods to confuse

matters.

The

walls of Troy were insurmountable (thanks to the help of the gods) and

despite the very bloody action between the two sides (often one-on-one

battles among the heroes) years went by with the Achaeans unable to

breach those walls ... although Achaean warriors, such as Ajax, laid

waste to the territories surrounding Troy.

Achilles kills Hector.

Years of failure began to break down Achaean morale ... and Achilles

abandoned the effort when he and Agamemnon fell into a dispute over a

concubine. The Trojans and Achaeans then finally met in open

field for battle which raged back and forth (thanks in part to the

intervention of the gods). Achilles returned to battle when his

friend Patroclus was killed by Hector ... and took on Hector directly

and killed him (dragging Hector’s dead body behind his chariot as he

circled the walls of Troy). Then the story as narrated in the

Iliad ended with Hector’s funeral.

The Achilles heel.

Other legends then take up the narrative from there. One stated

that Achilles was killed by an arrow shot by Paris, who struck

Achilles’s heel ... the only part of Achilles not protected by his

mother’s holding him there in order to dip him into the River Styx for

his eternal protection.

The Trojan horse.

The famous ending to the Trojan War (in its tenth year) was the story

told by the later Roman writer Virgil in his epic poem, the Aeneid,

(also mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey) about the wooden horse that was

left behind in front of the walls of Troy as the Achaeans finally

‘departed’ (though only just out of sight) ... which the Trojans took

as a sign of Achaean acknowledgment of Troy’s ultimate victory.

The Trojans foolishly rolled the horse inside the gates of Troy ...

despite the warning of the Trojan priest Laocoön to “beware of Greeks

bearing gifts”! Indeed, that night, as the Trojans fell into a

wildly drunken stupor, Achaean soldiers hidden inside slipped out of

the horse and opened the Trojan gates, allowing returning Achaean

troops to enter Troy to slaughter, rape, pillage and burn the city ...

to the ground.

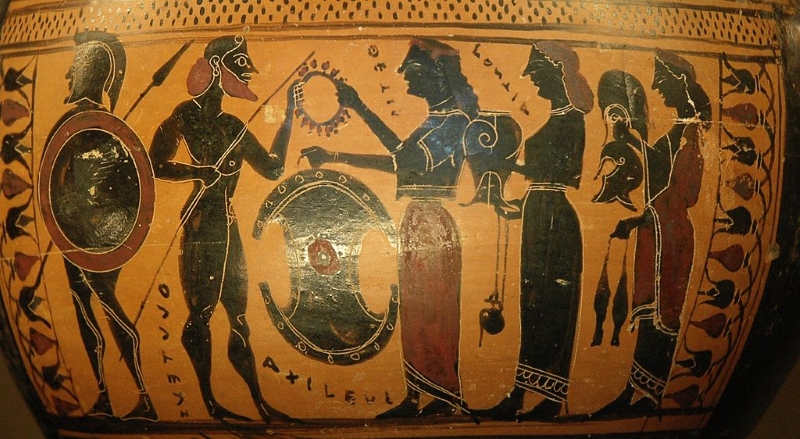

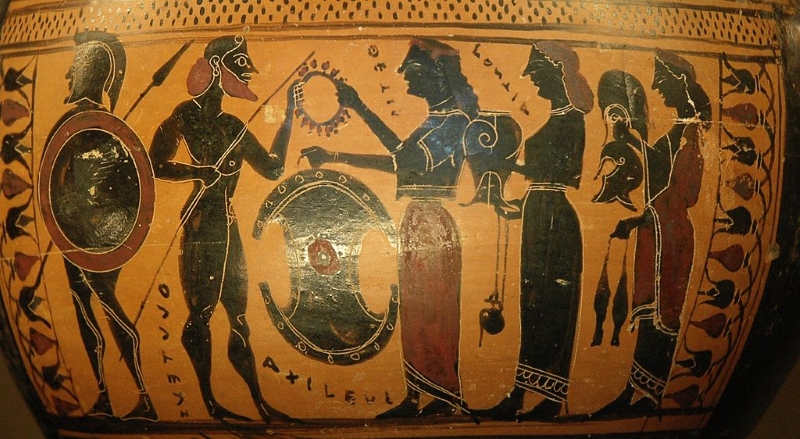

Thetis gives her son Achilles weapons forged by Hephaestus

Paris, Louvre Museum

Achilles treating Patroclus wounded by an arrow

Berlin, Altes Museum

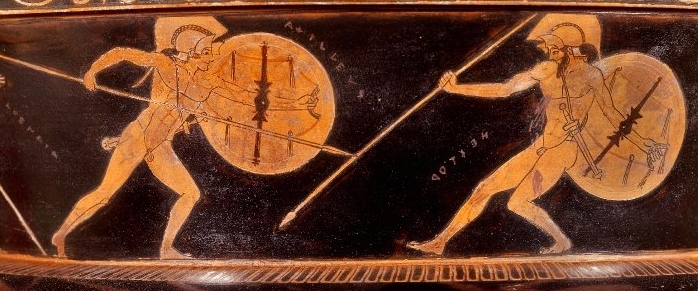

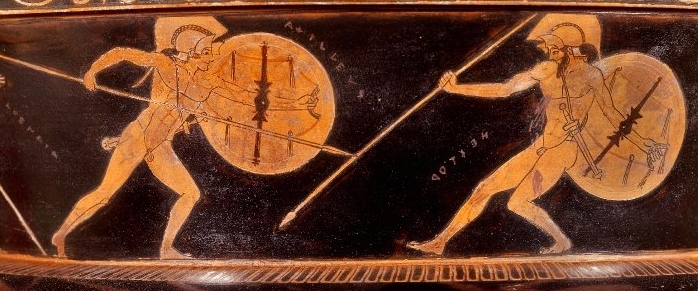

Hector fighting Achilles

British Museum

The earliest-known depiction of the Trojan Horse – from the Mykonos vase (c. 670 BC)

Archeological Museum of Mykonos

HOMER AND THIS HIGHER ORDER |

|

Homer was

an ancient bard (late 800s

or early 700s BC?) whose epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey,

gave tighter definition to this divine order. Homer portrayed

a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel gods who, from Mount Olympus,

called the shots on earth. It was often a wild and crazy affair.

Yet some small sense of equity or justice prevailed to force the gods to

behave (somewhat). Homer was

an ancient bard (late 800s

or early 700s BC?) whose epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey,

gave tighter definition to this divine order. Homer portrayed

a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel gods who, from Mount Olympus,

called the shots on earth. It was often a wild and crazy affair.

Yet some small sense of equity or justice prevailed to force the gods to

behave (somewhat).

In Homer's

saga, the Iliad,

the gods have taken sides in this war between the Greeks and the Trojans.

They serve as protectors over some of the key human players in the drama – most

notably Hector and Achilles.

But their

powers are limited – not

just by Zeus' dominion, but by forces which even Zeus cannot control.

The Greek heros can be protected by the gods – but their ultimate fate,

and the timing of such fate, not even the gods can set aside. Zeus

can hold the scale by which the length of the life of the hero Achilles

is measured – but Zeus himself cannot influence the outcome.

‘Fate’

has a higher power than even the Olympian gods.

Thus

it was that by the time of Homer the ultimate or cosmological Order was

beginning to be understood as somehow transcending the world of the

humanlike Olympian gods. Such Order is a mystery

– yet it is quite real.

Also, we see in Homer's work a very strong moral as well a religious or cosmological message. It seems that the sagas

of Homer were designed to touch the hearts of the aristocratic, more military

minded of the Greeks. Very likely this was some carryover from the

religions brought into Greece by the Greek (Aryan) invaders – offering

religious encouragement and moral justification for their dominant political

roles. The moral theme underlying these sagas was (not surprisingly)

that of valor – valor of the lone conquering hero in the face of overwhelming

odds and even death.a name="Hesiod"> |

HESIOD AND AN ORDERED PANTHEON

(flourised mid-500s BC) |

|

Anaximenes (anak-SI-muneez) was reportedly

a pupil of Anaximander's and the third in the trio of great Milesian philosophers.

He rejected most of Anaximander's theories about the world and the surrounding

universe. He felt that it was self-evident that the world was a flat

object, not a cylinder, and he rejected the idea of the earth just hanging

in a void of space. Like Thales, Anaximenes looked to a less mysterious

source of all things, to a primary material substance foundational to all

things, one more readily present in our observable world.

Anaximenes

concluded that the primal

substance of life was air or mist (pneuma) – an invisible

substance that filled all the universe. It could be both the source

of all things, and yet one of the created things itself – because of its

power to change form. Here too, it was probably natural for Anaximenes

to accord air the honor of being the primal substance or underlying material

of all things. Greeks commonly understood air to be the ‘breath’

or ‘spirit’ (also pneuma) of life, the source of the soul, and so

it was logical to think that air might be the primal substance of all things,

the soul or spirit of all life.

In any case,

he argued that through

a process of becoming more or less dense, air could change form.

Thus fire was air in its most rarified form. The natural progress

from there as air thickened was: wind, clouds, water, earth, and

stone. Also, the soul quality of air (as the Greeks understood it)

could explain movement, events, life itself.

All in all, Anaximines' theory of

the substance of life seems more complete than his Milesian predecessors.

It was truly a great intellectual accomplishment – though being founded

on a faulty premise, we find it interesting only for its methodology and

not for its conclusions.

|

|

Side by side

with the Olympian pantheon

existed a number of religious ideas and practices of the Greeks.

Some of it came in with the Doric invaders of the 1100s BC and some of

it either predated all Aryan Greek invasions – or else came in later from

the East. These tended not to be so orderly but instead seemed to

anticipate the disorder of life caused by gods who needed to be appeased

directly (through sacrifices) and often.

Among the

Greeks one of the most

persistent and widely popular of such non-Olympian religions was Dionysianism.

This was a rather wild fertility cult that perhaps predated the Greeks

– a cult which managed to get a quite a hold on the Greeks at some point

in their history.

The Thracian story of Dionysus/Bacchus

seems to have developed many versions over the centuries--especially as

the story was assimilated into Greek theology. It may have originally included blood sacrifice

– perhaps even human as well as animal. Indeed part of the original

Dionysian myth brings the hero Dionysus to a bizarre death at the hands

of female devotees, who literally tore him limb from limb in a religious

frenzy.

One of the major versions

tells us that Dionysus/Bacchus (called also Zagreus) was the "illegitimate"

son of the god Zeus and the goddess Persephone. He was torn to pieces and

eaten as a boy by the Titans--set up in their fury by a jealous Hera, the

wife of Zeus. The Titans then themselves took on divinity from such a grisly

meal. But in turn, the Titans were struck by lightning--and turned to ashes.

But from the ashes of the

Titans grew the human race: which is thus part divine (Zagreus) and part

evil (the Titans)!

But also: Bacchus' heart was

not eaten but given to Zeus, who used it to bring Bacchus back to life.

Some versions of the story tell that this happened as Zeus swallowed the

heart himself. Other versions tell that this happened when the heart

was given to Semele--who swallowed it and gave birth to Dionysus.

Another version of the story

tells us that Dionysus was reputedly the son of Zeus and Semele (Phrygian

goddess of the "earth" or "Earth Mother"). By mysterious circumstances,

Semele was destroyed by Zeus' power of lightning--along with the boy.

But Zeus rescued the boy from the ashes, taking him up and encasing him

in his thigh--from which he was reborn later in his maturity.

According to most accounts,

Dionysus traveled the world to teach the cultivation of grapes (and to

spread his worship among men).

According to several different

accounts, Dionysus was killed by either a group of crazed women--or by

his own his own mother--in a frenzy of the very worship which he introduced

to the people.

Thus the tearing and eating

of raw flesh of a sacrificial animal (symbol of Bacchus) was understood

to impart divinity to the devotee--as it did the Titans.

Being a

fertility cult, it was a

rite closely associated with the growing season – especially of the grape,

the source of the Greek's precious wine. Drunkenness was thus a natural

accompaniment to the festivities.

It seems however that gradually this

worship form was toned down by the Greeks – until it became a respectable

worship form involving even the Greek aristocracy (who were always the

bastions of original Olympian worship). Indeed, it was the

refinement of Dionysianism that produced Greek drama – for it was at the

Dionysian festivals that the famous Greek playwrights (Sophocles, Euripides,

Aristophanes, etc.) offered their new theatrical pieces to their Greek

audiences.

|

|

Orphism seems to

have been part of

that effort to tame Dionysianism. But even this later development

within Dionysianism is so clouded with mythology that it is hard to tell

how or where it all started. The figure of Orpheus stands at the

heart of this Dionysian "movement." There may have actually been

a religious reformer who gave rise to the Orphic myth. But by and

large, the Orpheus that has come down to us in story or myth seems to belong

to the world of the gods rather than men.

The common story was that he was the

son of the Thracian king Oeagrus (or some Thracian god) and a Muse.

From his mother's side he inherited great musical talents. From his

father's side he inherited his love of adventure.

As an adventurer, he took part in

the Argonaut expedition of Jason--where he played a key role with his music

making.

Later stories have him as a wandering

philosopher in search of knowledge.

He married Eurydice, who was bitten

by a serpent and died. Being inconsolable over this loss, Orpheus

went down to Hades to get her back. He wooed her from the gods with

his beautiful music--who let her go. But they did so on the promise

that she would not look back on her way out of Hades. But she failed

in this important stipulation--and was returned to Hades as a ghost.

As a result, Orpheus vowed to have

nothing more to do with women. But the Thracian women (or frenzied Maenads?),

during a Dionysian orgy, tore him apart--the same fate that met Dionysus.

(Beware of Thracian women!)

Ultimately Orphism developed into a

theological refinement of the Bacchic religion. At first it was strongly

persecuted by Bacchic priests. But eventually it became established

within the Bacchic system.

Orphic teachings that began to come

forth over time had much in common with Hinduism and Buddhism (perhaps

from mutual Aryan roots). Orphism held a sense of dualism about human

existence: 1) the earthly or physical existence (derived from the Titans)

and 2) the heavenly or spiritual existence (derived from Zagreus or Bacchus

or Dionysius).

Within Orphism, earthly life was

seen only as a merciless round of pain and trouble (product of evil).

Though we humans belong to the heavens, to the stars (as semi-gods), we

are also bound to life by a cycle of death and rebirth. The goal

of life: escape from earthly existence and release to eternal life.

But the fate for most folks was really

not escape--but rather a period of death (and torment) and then rebirth--according

to the merit of one's earthly deeds.

Thus Orphism held much concern about

the after-life. It included instructions on how to enter the after-world.

Likewise, it sought to reform Bacchic or Dionysian worship in order to

increase one's spiritual nature--and diminish the portion of one's physical

being so as to become one with Bacchus (or Dionysus).

Orphism

shared many features in common

with another worship form found further to the East: Hinduism.

Orphism developed a theology of reincarnation and transmigration of the

souls through endless cycles of birth, growth, decay and death – in which

escape from the grip of this eternal dance was the desired goal of the

Orphic devotee (as with Hinduism's offshoot, Buddhism)

Orphism, as a worship or religious

form also had various kinds of purity rituals designed to help the devotee

avoid certain types of contaminating influences. Thus the most rigorous

practitioner avoided animal food (as with the Hindus) except for sacrificial

rituals. Further, despite its connection with wild Dionysianism,

the Orphic devotee took wine only as a sacramental act--as a symbol indicative

of the mystical enthusiasm of one who sought union with the god Bacchus--or

Eros!

Orphism

shared many features in common

with another worship form found further to the East: Hinduism.

Orphism developed a theology of reincarnation and transmigration of the

souls through endless cycles of birth, growth, decay and death – in which

escape from the grip of this eternal dance was the desired goal of the

Orphic devotee (as with Hinduism's offshoot, Buddhism)

|

Return to the section: Early Philosophical Development

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

|

The fabled Trojan War

The fabled Trojan War

Hesiod and an ordered pantheon

Hesiod and an ordered pantheon

Homer was

an ancient bard (late 800s

or early 700s BC?) whose epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey,

gave tighter definition to this divine order. Homer portrayed

a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel gods who, from Mount Olympus,

called the shots on earth. It was often a wild and crazy affair.

Yet some small sense of equity or justice prevailed to force the gods to

behave (somewhat).

Homer was

an ancient bard (late 800s

or early 700s BC?) whose epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey,

gave tighter definition to this divine order. Homer portrayed

a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel gods who, from Mount Olympus,

called the shots on earth. It was often a wild and crazy affair.

Yet some small sense of equity or justice prevailed to force the gods to

behave (somewhat).