1. THE ANCIENT GREEK LEGACY

THE ATHENIAN CONTRIBUTION

The 500s to the 300s B.C.

CONTENTS

The ancient Greek political-intellectual The ancient Greek political-intellectual

legacy

Greek origins Greek origins

Early philosophical development: Early philosophical development:

Materialists versus Mystics

Athens' rise to glory Athens' rise to glory

Athens' political-social-moral decline Athens' political-social-moral decline

The Big Three: Socrates, Plato and The Big Three: Socrates, Plato and

Aristotle

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 31-52.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

BC

1900s-1500s? Mycenaeans (or Achaeans) migrate from from S.W. Asia into Greece setting up city-states headed by kings (Athens,

for example)

1200? Possible time of the Trojan War (mainland Greeks v. Trojans)

1150? Doric Greeks begin their invasion of Mycenaean Greece ...causing – or taking

advantage of – a "Dark Age" that descends upon Greece (1150-750 BC)

1000s Doric pressures inspire Greek migration to Asia Minor: Ionians from Attica to Western shores of today's Turkey

(Ionia with its city of Miletus); Aeolians to the Northwestern shores / Dorians to the

Southern shores and then Crete

Eventually Sparta (in the Peloponnesian Peninsula) develops as the

leading Dorian power; Athens continues as a strong, independent Achaean power

700s Homer (early) composes the Iliad and the Odyssey ... central to Greek self-understanding ... with life controlled by competitive human-like

gods

Hesiod (later) composes the Theogony ... presenting a more orderly account of the behavior of the Olympian gods

700s-600s

Greeks settle at both the Eastern (Syria) and the Western

Mediterranean coasts (Sicily and Southern Italy or "Magna Graecia,"

Southern

France, even Spain)

c. 620 Draco institutes a tough ("Draconian") constitution for Athens

Early 500s Thales of Miletus introduces Materialism into Greek thinking: water as the foundation of all matter

Solon offers Athens a more "democratic" constitution

Mid-500s

Anaximander follows up on Thales' Materialism: all matter seeks

unity or harmony with some invisible, formless substance

Anaximenes sees all life derived from air (pneuma) in varying thhicknesses

509

Cleisthenes completes the "democratization" of the Athenian

constitution

c. 500 Pythagoras, teaching in Magna Graecia, develops math and Orphic mysticism; sees all life as an imperfect

reflection of the divine Logos or higher Order

Heraclitus sees life as "process" not substance ... like fire ...

process seeking unity with the Logos

Early 400s Empedocles afirms that the universe is made up of earth, air, fire, and water

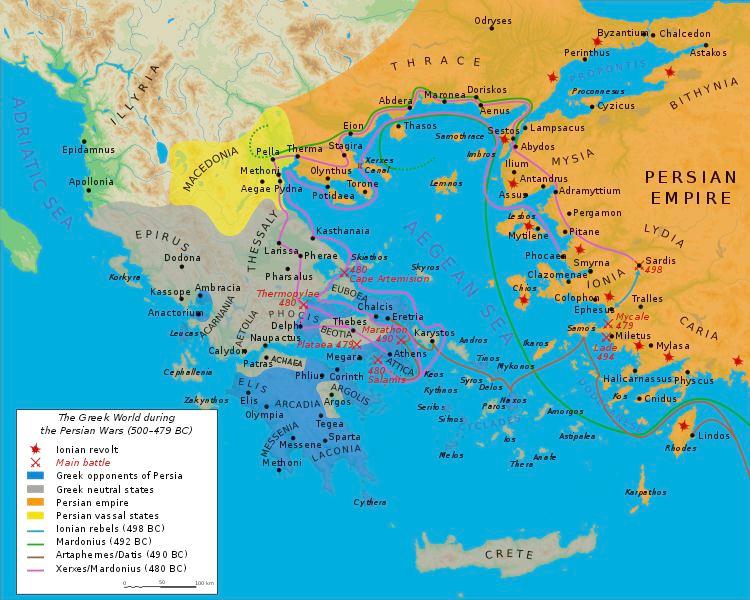

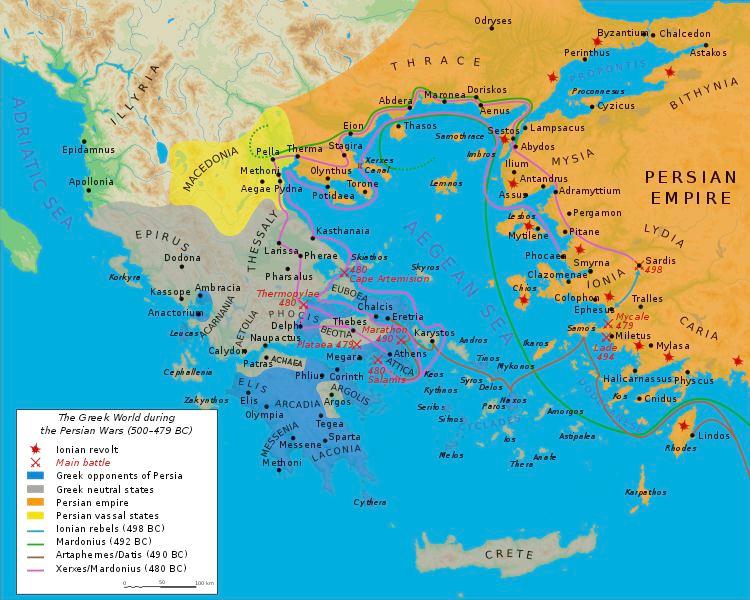

490

The Batle of Marathon begins the Greek war with the Persians

480

Battles do not go well for the Greeks at Thermopyla and

Artemisium (Athens and other Greek cities are burned badly)

... but things go strongly in Greek favor at the sea battle at Salamis

479

At Plataea and at Mycale the Greeks destroy the Persians. End of

the war!

472 Themistocles, a commander at Marathon, is ostracized by the Athenian Assembly

Mid-400s Anaxagoras sees the Eternal Mind (Nous) behind the surrounding material order

Protagoras (Sophist) sees "Truth" simply as that which is useful

Athens is at the height of its glory under Pericles (r. 461-429 BC)

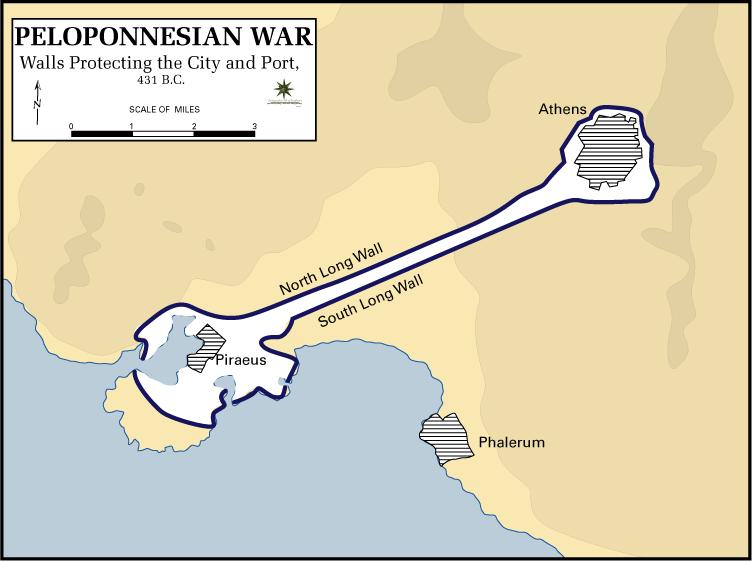

431

Sparta organizes an anti-Athenian revolt ... beginning the

Peloponnesian Wars

First round: 431-421 BC ... Pericles killed in battle (429 BC)

Second round: 421-404 BC ... Athens crushed as a power

c. 400

Democritus takes Greek Materialism even further, with his theory that

all things are derived from miniscule atoms

... which come together (but also break down) to form all life ... even human life

399

Socrates – who

teaches that Truth is real and absolute, not subject to speculation

(such as the Sophists are noted for) – is condemned to death by the

Sophist-led Athenian Assembly

c. 375 Plato publishes his Republic ... describing a "just" or properly-moral city-state

c. 350 Aristotle published his Politics and Nicomachean Ethics in defining his own idea of a moral society ... how it is structured and how it operates

THE ANCIENT GREEK

POLITICAL-INTELLECTUAL LEGACY |

It

is of vital importance to note that America's "Founding Fathers" who

gathered in Philadelphia during a very hot summer in 1787 to draft a

new Constitution uniting their thirteen1

newly-independent states were college educated – or at least

self-taught in the intellectual areas that a college education would

have included – and were therefore well-informed about the ancient

Greeks … and the political and intellectual lessons to be drawn from

Greek history. And it was a huge legacy … highly instructive of

both the good – and the bad – in any society's political and

intellectual development. Thus this Greek legacy would factor

hugely in how those that were called to put together a new American

Constitution would finally design or "frame" this most fundamental

American political foundation. They knew to build on the positive

part of the Greek – especially the Athenian – legacy … and avoid the

horribly negative parts of that same legacy.

At the heart of that legacy was the immense intellectual energy that a

large number of Greek individuals were able to generate. Greek

scholarship brought Greece forward out of its original neolithic

(farming and animal herding) world … and into a highly civilized world

– urbanized on the basis of the very independent Greek

city-states. Such development sparked deep inquiry into a newly

awakening world … and what that meant to the Greeks in terms of the

social "progress" they were seeking to achieve.

But unfortunately, that same highly intellectual spirit would also come

to lead the Greeks, notably the leading Greek city-state Athens, into

very self-destructive political rationalizing. Tragically, the

Athenian "Sophists" (wise ones!) of the 400s and 300s BC used their

intellectual gifts to lead a very gullible Athenian citizenry to take

up very self-destructive political causes … ones that led to a series

of totally ruinous wars.

Thus the cleverly rational Greek Sophists demonstrated to the American

Framers the dangers of human "reason," always clever – but hardly the

kind of Truth that elevates life. After all, half of these

Framers were lawyers, and already knew that a very convincing rational

argument laid before a jury on behalf of a client of theirs was simply

the business they offered their clients. For the jury, deciding

the actual "Truth" of a dispute involving a "rational" defense put

before them by opposing – but equally clever – lawyers was a very

delicate, often very uncertain, matter.

Thus the Framers knew very well that Reason itself never equaled

Truth. Reason merely advantaged one side of a dispute over its

opponents. The actual truth of things thus always stood above –

and often well beyond – human reason. The Greeks proved that

quite clearly.

"Democracy" as Greece's great legacy.

Undoubtedly when Greece is remembered today as a major contributor to

Western civilization it is in the area of "democracy" that Greece – but

especially Athens – is mostly noted. But actually, for almost two

thousand years, the Greek concept of "democracy" dropped from view or

discussion ... and for good reasons.

Democracy or rule by the people (the Greek demos) is an almost sacred

concept today ... but one not well understood by those very ones today

loudest in their promotion of the glories of democracy. The way

they go at this matter comes from their instincts favoring a purely

rational Humanism or Idealism … not from actual experience across the

ages.

Greek government by the demos at one point served the Greeks well ...

and then proceeded to dishonor that record – especially in the leading

Greek city-state of Athens – by engaging in very stupid politics,

"democratic" politics that ultimately brought Athens down from its

power and greatness. The Athenian demos, as it turned out, was

easily led by unscrupulous politicians, who manipulated the masses into

making horrible political decisions ... such as ordering the death of

Athens' premier philosopher Socrates, because he annoyed these

unscrupulous politicians with his constant criticism of their

behavior. That same stupidity was found also in the decision of

the Athenian demos to turn a deaf ear to their fellow Greeks who

complained that the money being sent to Athens, as Greece's leading

city-state, to equip a Greek army designed to protect Greece from the

Persians, was being used instead to dress up Athens with fancy new

buildings and other public works. The other Greek city-states

would have been happy to have kept this money, if it was not going to

the intended purpose of Greek defense, to undertake the same

architectural upgrade to their own communities. Ultimately,

Athens' selfishness led to a horrible series of Peloponnesian Wars

among Greece's various city-states, (431-378 BC), wars that finally

destroyed not only Athens politically, but much of the rest of Greece

as well.

Consequently "democracy" was not well remembered in the West. As

we have already noted, the philosopher Aristotle himself (who was

widely read by educated Westerners ... up until recently), made it

clear that it is not the form of government – whether government by

one, a few, or the many – that produces better government ... but

instead the moral intentions of those who do govern. Dictators

are not the only problem affecting mankind. Democracies (Hitler’s

Germany was actually a "democracy") can be horrible, if horribly led.

Thus it is that the men (who had read their Aristotle!) who gathered in

Philadelphia in 1787 to put together a new American Constitution in

order to perfect the Union of their thirteen states were definitely not

intending to create a democracy. They instituted instead a

"republic" built on a regime of foundational law … which itself called

for a "mixed" system, one of political checks and balances. The

Republic's Constitution was carefully designed to permit, yet restrict,

popular participation in the nation’s politics – out of a fear of

democratic instincts getting out of control. Their new Federal

Union would include government by one (the President), the aristocratic

few (the Senate) and the democratic many (the House of Representatives)

... understanding that this system would work only when all three forms

of rule worked together. This was to prevent any one of the three

forms of government to take over the other two and establish a monopoly

on power ... which unchecked always leads to great social evil.

It would be until only the beginning of the 20th century – notably with

the arrival on the scene of the highly Idealistic American President

Woodrow Wilson, who saw "democracy" as the cure-all for the world’s

ills – that "democracy" would come to have the glamor and intense

devotion that it does today. Thus it is only recently that

Western political philosophers have rejected the wisdom of the ancients

and moved to the call for pure "democracy" both at home and abroad.

This is so much so the case that it is now almost religious heresy to

voice any hesitations about bringing (especially imposing) democracy as

some kind of wonderful benefit to the world's societies … without

having also laid the accompanying moral groundwork that democracy would

need in order not to lead to horrible social chaos and even cruel

tyranny. Democracy is not a basic human right. It is a

major social responsibility.

1Actually,

only twelve of these new states sent representatives to Philadelphia

that summer … because tiny Rhode Island was afraid to join the new

Union, fearing it would lose all sovereignty to a new governing

authority. Rhode Island would, however, soon join … when it was

clear that the new Constitution protected the states' authority –

rather than removed it.

|

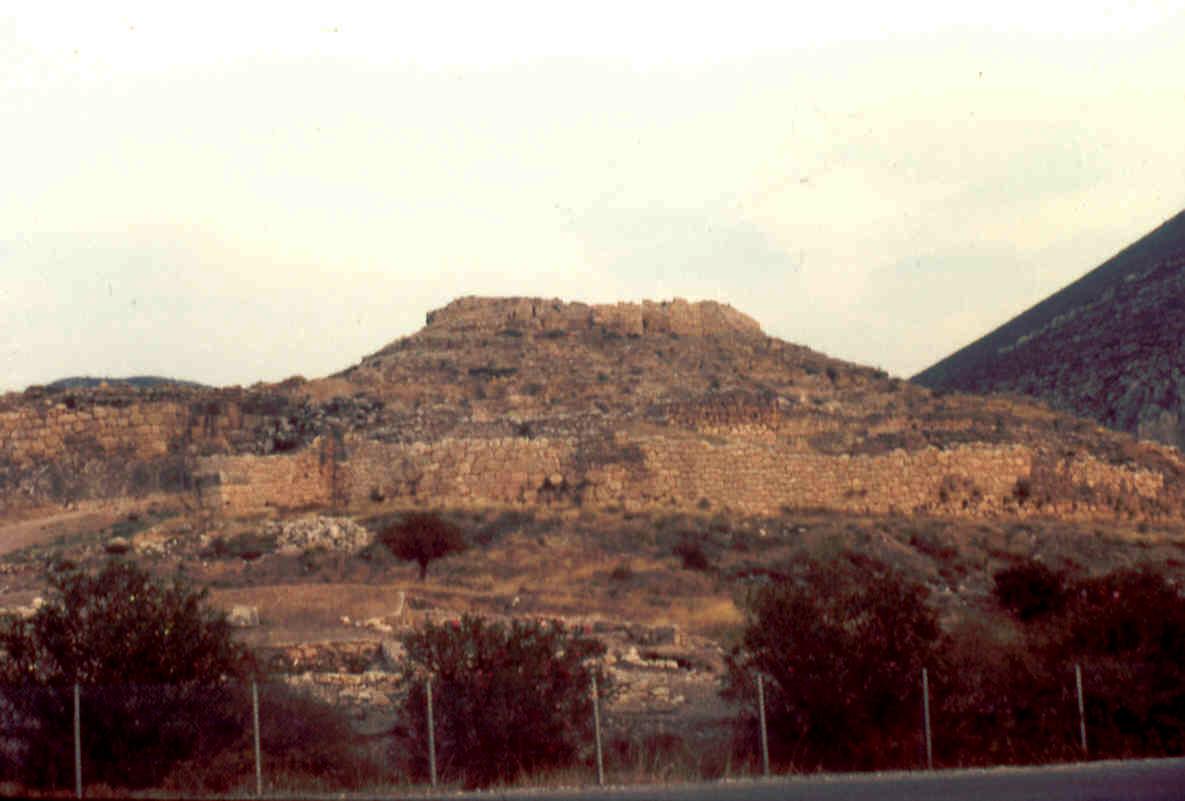

The Mycenaeans or Achaeans

At

some very distant point in time, dating anywhere between 1900 BC and

1500 BC, a number of different Aryan speaking peoples moved westward

from southwestern Russia and invaded/settled in wave after wave into

the land we know as Greece.

These

invaders, sometimes identified as "Mycenaeans" or sometimes as

"Achaeans," spoke an early form of Greek and would become known to

later Greeks as the military heroes in Homer's epic war story or poem,

the Iliad. There on that southernmost Peloponnese Peninsula they

established fortified towns in the valleys between the many mountainous

ridges that reach down to the sea and divide Greece into a number of

distinct geographic units. Each town was headed by a

chieftain or warlord (or "king" as we later termed them).

Eventually

a number of important Greek cities, such as Athens and Thebes that

developed later, could easily trace their origins back to Mycenaean

times.

|

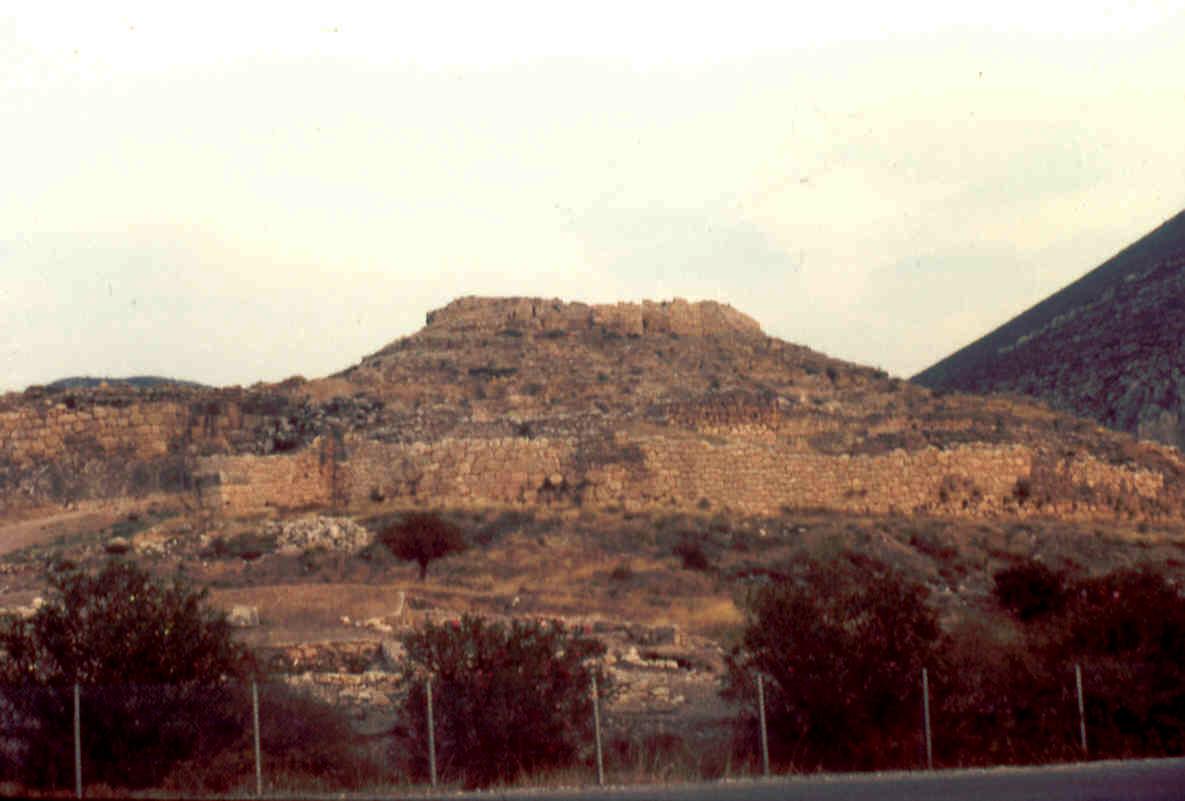

Mycenae at a distance

Miles Hodges

Mycenae

Miles Hodges

The approach to Mycenae and

the Lions Gate

Miles Hodges

Details of the Lions Gate

Miles Hodges

A view of entrance from inside

the walls

Miles Hodges

House foundations inside

Mycenae's walls

Miles Hodges

The Royal Tombs

Miles Hodges

The Citadel at Mycenae

Miles Hodges

The Citadel at Mycenae

The Citadel at Mycenae

Miles Hodges

View of the surrounding countryside

from the Citadel at Mycenae

Miles Hodges

A princely death mask of

gold ("Mask of Agamemnon")

from the Upper Grave Circle at Mycenae - 1500s

Mycenae – Lion head of thick

plate gold

From the upper grave circle

Athens - National Archeological

Museum

Gold cup from the Upper Grave

Circle at Mycenae, 1500s BC

Gold pendant of a goddess – from the women's grave in the Upper Grave Circle,

Mycenae, 1500s BC

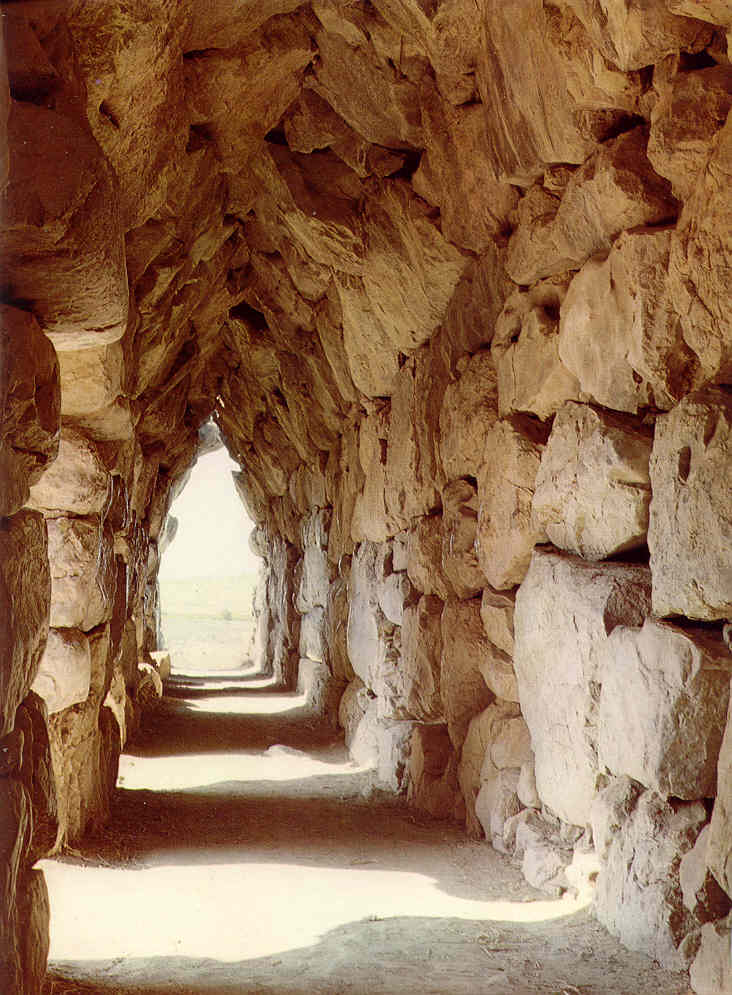

Other Mycenaean era sites and archeological findings

Tiryns

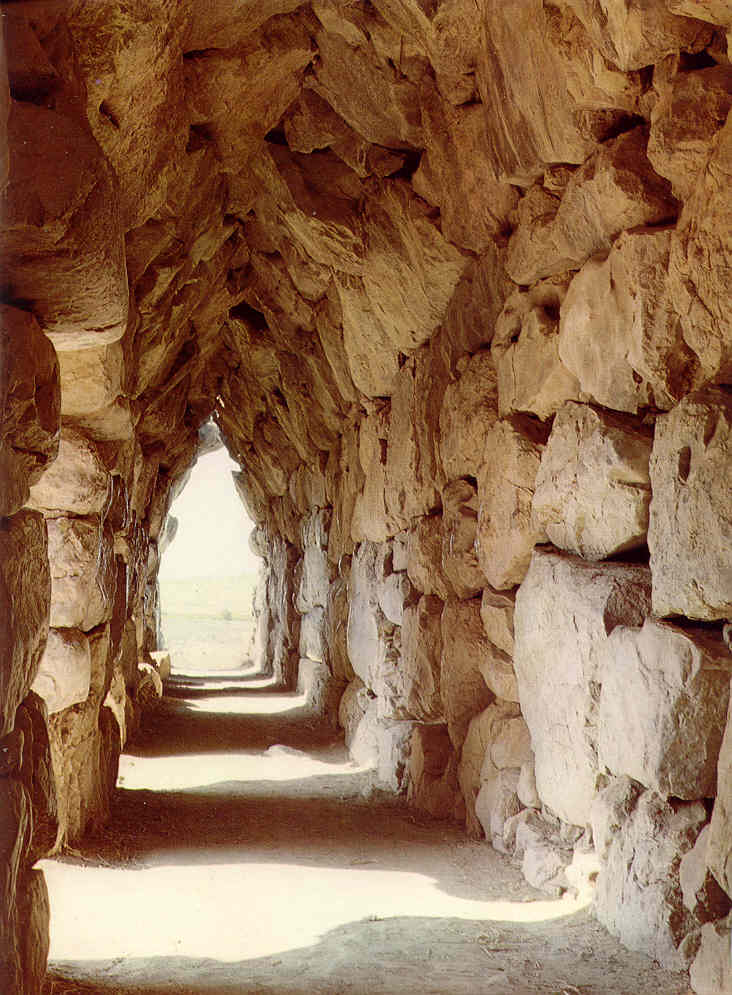

Tiryns – a general view

Entryway through Tiryns'

thick walls

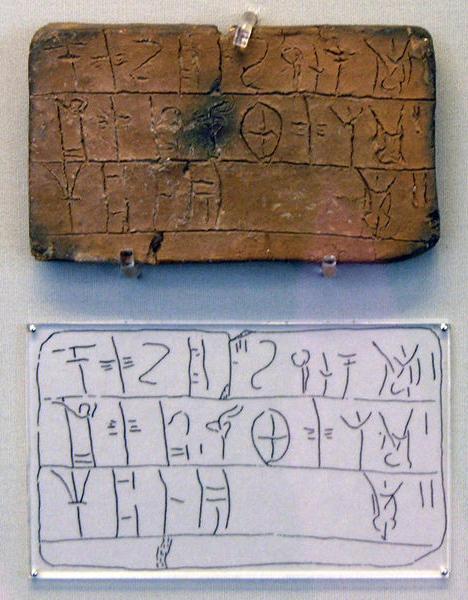

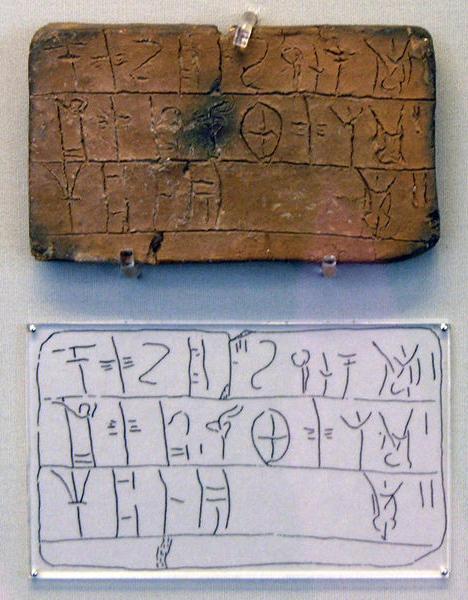

Mycenaean tablet inscripted

in linear B coming from the House of the Oil Merchant

The tablet registers an

amount of wool which is to be dyed

National Archeological Museum,

Athens

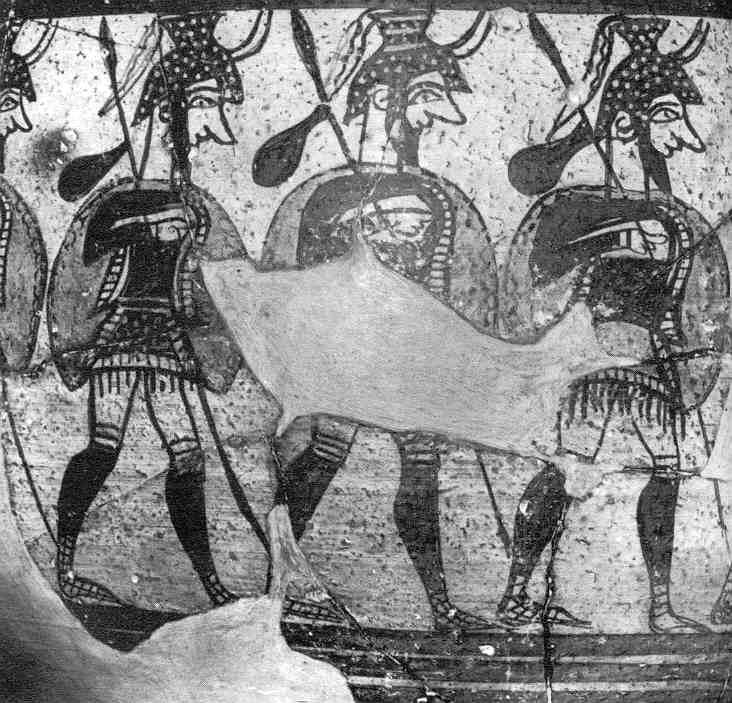

Achaean armor made from boars'

tusks and bronze – 1400s BC

Achaean warrior in boar's-tusk

helmet. Ivory – from a chamber tomb at Mycenae, 1300s BC

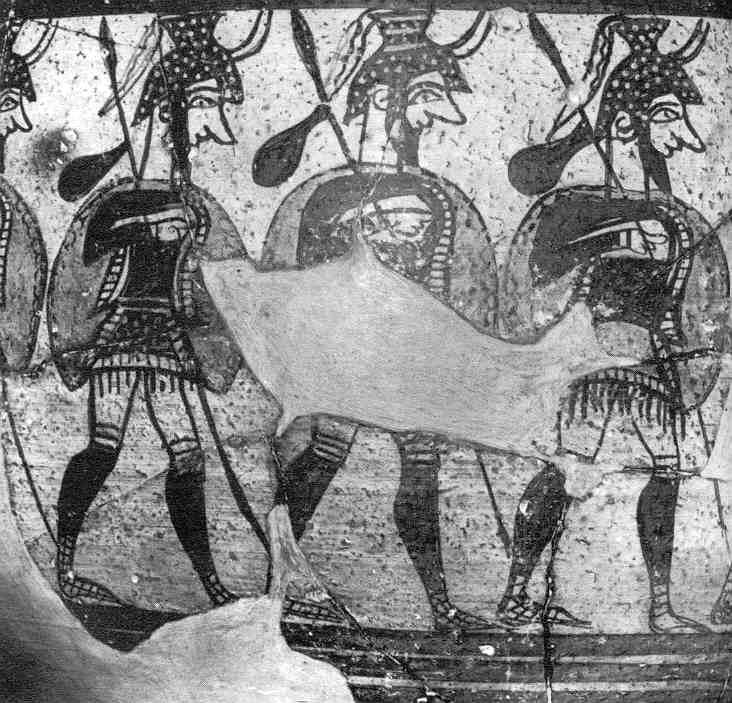

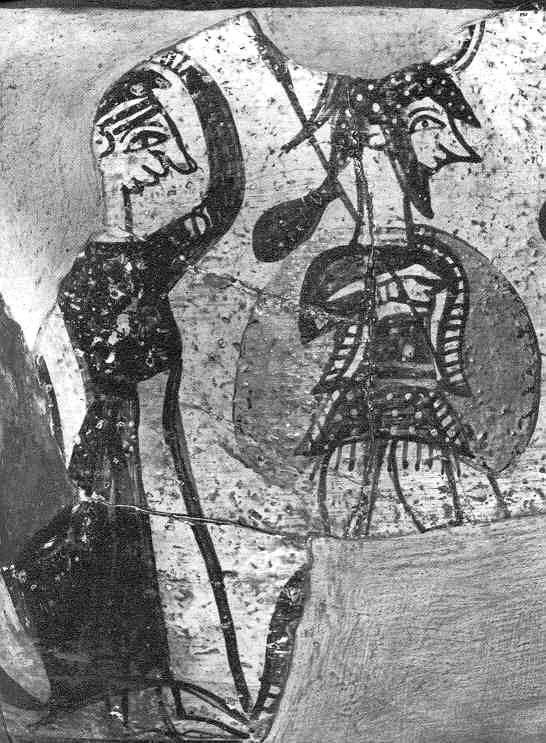

Soldiers marching against

the (Dorian?) barbarians

– from the "Warrior Vase" at Mycenae, 1100s BC

Athens - National Archeological

Museum

A woman laments the departure

of the soldiers –

from the "Warrior Vase" at Mycenae, 1100s BC

Athens - National Archeological

Museum

|

The Dorians ... and a Greek "Dark Age"

But

this Mycenaean/Achaean strength eventually began to decline, and after

approximately 1150 BC Greek culture fell into a 400 year-long Dark

Age. This was either caused by, or led to, yet another wave of

Greek invaders from the Northeast, the "Dorians." All

archeological evidence seems to indicate that probably (though not

certainly: debate lingers on) the Dorians disrupted life in

Greece in a very major way.

Certainly

the Doric invasion set off a reactive wave of Greek migrations in

around 1000 BC – principally to the shores of western Asia Minor.

Ionians from Attica (around Athens) retreated across the Aegean to the

central western shores of Asia Minor (to Miletus) and gave their name

"Ionia" to this particular region along the Asia Minor coastline.

Aeolians (perhaps a later group of Greeks to appear on the scene)

settled the north western shores of Asia Minor. Dorians

themselves eventually continued their own migration across the Aegean

to the shores of southwestern Asia Minor and then onward to Crete.

In

any case, the warlike Dorians eventually settled themselves into the

Peloponnesian peninsula – where they ruled over the helots, the

enslaved or enserfed Greeks who had originally lived in the area.

Eventually Sparta grew up as the leading city-state at the heart of

Doric culture – famous for the intense military discipline all its

citizens (women as well as men) were put under. But

interestingly, Athens (and its hinterland of Attica) managed to fend

off the Dorians – and retain its older Achaean culture.

Greece's "Archaic Period" (700s – to the late 500s BC)

In

the 700s BC Greece began to experience a commercial revival, growth of

its population – and emergence of political powers in reviving Greek

towns in the form of local aristocracies (rule by the heads of

prominent families). But prosperity also strengthened the power

of the more numerous commoner class, who found champions in the form of

tyrants – who would use their political power to support the political

cause of the Greek lower classes. Political revolutions of sorts

thus shook the Greek world as new prosperity put power in the hands of

all sorts of people. As a result democracy (rule by the common

people or demos) – or something like it – resulted in a number of

cities.

This

rise of the common classes however inspired a strong political reaction

in Sparta, where a small elite of Spartan military citizens, who ruled

over the vast numbers of subject peoples in surrounding towns and

villages, took an ever-tougher stance of rulers over ruled – creating

Sparta's famed military aristocracy.

More Greek colonization around the Mediterranean

With

this economic revival of Greece there was also a large increase in the

population – causing a serious strain on Greece's available farmland to

feed that population. However, the surrounding seas, which the

Greeks viewed not as a barrier but as a source of life (in fact a

superhighway for them to move across), offered them an escape from

their problems. Thus, excess population was sent out to create

new settlements or colonies – extensions of sorts of the sending

cities. A new wave of Greek migration thus developed.

During

the 700s and 600s BC Greeks sailed east and west and discovered lands

that they could colonize with their excess population (much as other

cultures were doing at the time, notably the Phoenicians – located

along the Syrian coast – with whom the Greeks had active commercial

relations).

From

the city of Corinth colonies were established to the West on the island

of Sicily and on the southern Italian peninsula (this would eventually

come to be called Magna Graecia or "Greater Greece"). One of

those colonies, Syracuse (founded in 733 BC), soon became a major city

by its own right. Some of the Euboean towns (just north of

Attica) sent settlers to the Syrian coast. From Miletus and other

coastal towns in Asia Minor (a region known as Ionia) settlers were

sent through the Dardanelles straits into the Black Sea where they then

established numerous Greek towns around the coast. Settlers also

headed south to the Egyptian and Libyan coasts of Africa. Others

sailed west beyond Sicily and established towns along the coast of what

is modern day France (notably at Marseille). By the 500s BC they

were reaching to Spain and northern Italy.

Thus

in the course of the 600s BC "Greece" came to describe an area much

larger than the land we today call Greece. In those ancient days

"Greece" encompassed a whole huge area along the northern half of the

Eastern and central Mediterranean Sea. And if we include the

various Greek cities planted along the coast of the Western

Mediterranean (such as Marseilles in southern France) we are describing

a culture that was very extensive.

Soon

Greek towns along the Western coast of Ionia (Western Turkey) and Magna

Graecia (Sicily and Southern Italy) would achieve tremendous cultural

growth of their own – often surpassing in quality the level of culture

of the sending cities back home.

|

Greek colonization around

the Mediterranean

Wikipedia - "Ancient

Greece"

EARLY PHILOSPHICAL DEVELOPMENT |

The Greek cosmic vision: Materialism versus Mysticism

It

is easy to look to the ancient Greeks for the startup of what we have

come to know as "Western culture." The Greeks were great

thinkers. Although they had started out as much of the rest of

the world with rather neolithic ideas about how events on earth were

regulated by gods and goddesses in the heavenlies above (and in the

depths of the earth below), some of them began to notice a high degree

of order around them, one not so easily explained by the doings of

rather human-like and human-acting gods and goddesses. Greek

thinkers began to explore the possibilities of other things being the

source of this order. Thus Greek philosophy was born. And

thus the Greeks put Western culture on the road to intellectual and

spiritual enquiry – one still very much a part of Western culture to

this day. And it all began so very long ago.

This Greek legacy was so strong that it even influenced deeply the

Roman world that eventually took over the Mediterranean heartland from

the Greeks, and indeed also the Christian society that emerged from the

decline of Rome, and even the modern secular world that would one day

in turn challenge the thousand-year tenure of Christendom. This

legacy would be strongly philosophical and ideological in its early

shaping of the West’s fundamental cosmology or world view – but in the

process would take on not one but two distinct forms: on the one hand

an earthy philosophical materialism … and on the other a lofty

mysticism.

From Chaos to Order.

Greek culture had grown up in a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel

gods who, from Mount Olympus, called the shots on earth. It was

often a wild and crazy affair – as witnessed in the sagas of Homer in

his works, the Iliad and the Odyssey. But by the 700s BC, the poet Hesiod was describing in his well-received work, Theogony,

an Olympic realm in which the gods themselves lived under some kind of

a divine order – with Zeus as the presiding figure over this order.

For more on The Trojan War, Homer, and Hesiod ... but also Dionysianism and Orphism

Philosophical Materialism.

By the 500s BC a number of Greek thinkers were already dismissing the

idea of human-like gods living atop Mount Olympus directing life on

earth, especially concerning the affairs of the Greeks

themselves. From the Easternmost reaches of the Greek world in

Western Asia (Ionia in modern-day Turkey) to the Westernmost reaches of

the same world in Southern Italy and Sicily, a number of Greek thinkers

or philosophers were reflecting deeply on this matter of a basic order

underlying all creation … an order that seemed to work quite

"naturally" (as in its very nature to do so) rather than as a result of

some kind of Olympian or divine manipulation.

It

is perhaps surprising to note that it was not in Athens or the Greek

mainland, but in the eastern Greek realm of Ionia across the Aegean

Sea, that this program of "natural science" really got underway.

In the Ionian town of Miletus, the well-traveled teacher Thales (c.

624-546 BC) showed his students the power of mathematics and

engineering in the construction of everything from pyramids to

ships. But he was also the first Western philosopher on record

(and thus acknowledged as the "Father" of Western philosophy) to seek

to find the substance that was the source – material in nature … not

spiritual or divine – that was the foundation of all reality. And

he was certain that it was simply the primary physical reality:

water.

His

legacy was then picked up by Anaximánder (most probably a student of

Thales) and then carried forward by Anaximander's student

Anaximénes. Anaximander (c. 610-547 BC) claimed that it was the

balance of forces inherent in all matter (cold v. hot; wet v. dry) that

formed the underlying dynamic moving all of life forward. Then

Anaximenes (mid-500s BC) went back to Thales' single-substance theory …

except that he claimed that it was pneuma

(breath or spirit) that was the primal material and the source of all

life. But according to Anaximander, pneuma could take on mass,

even take the form as fire, as well as form the foundation for all material

substance.

And thus the "Miletus Triad" opened up the materialist pathway for

Greek philosophy to take. Thus these materialistic philosophers

were early forerunners of our modern scientists – with this same

tendency to look to the material order for answers to the "natural"

structure and dynamics of the universe.

According to these early philosophers, Greek gods had no role to play in the dynamics of life.

For more on The Miletus Triad For more on The Miletus Triad

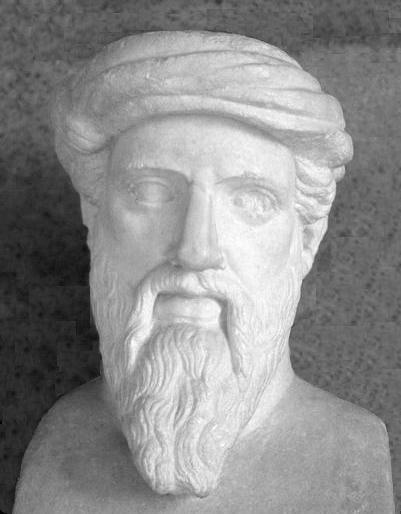

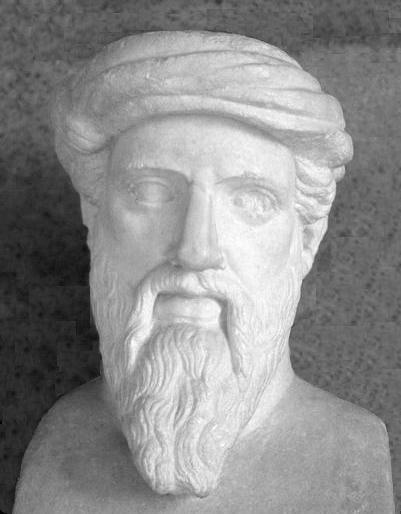

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570 to c. 480 BC)

But

the materialism of the Miletus school was answered by another

individual located on the opposite side of the Greek world – in

Southern Italy at Croton. Today he is remembered for his skill in

the field of mathematics … for instance, the discovery of the

"Pythagorean Theory" of the dimensions of a right triangle, his

discovery of the mathematical rules for the musical harmonies or

scales; his assurance that the sun, moon and earth - as well as the

universe itself – are all perfect spheres. But

the materialism of the Miletus school was answered by another

individual located on the opposite side of the Greek world – in

Southern Italy at Croton. Today he is remembered for his skill in

the field of mathematics … for instance, the discovery of the

"Pythagorean Theory" of the dimensions of a right triangle, his

discovery of the mathematical rules for the musical harmonies or

scales; his assurance that the sun, moon and earth - as well as the

universe itself – are all perfect spheres.

But unlike the Miletus School of Materialist philosophy,2

Pythagoras was noted for being a mystic … even of the Orphic school –

rather than a materialist. Unfortunately, it is hard to say what

his cosmological beliefs actually happened to be … because he worked

with his students in mystic secrecy … although elements of his thinking

slipped out publicly so that we can see that he was an exceptional

philosopher in the mystic category as well.

We know that his philosophy was closely related to Orphism3

… although we can't tell whether Orphism impacted him greatly – or he

impacted the Orphic school greatly. But certainly, the Orphic

mysteries became much more sophisticated in his days … a Greek

philosophical development for which Pythagoras is probably greatly

responsible.

As a mystic he looked beyond the mathematical precision of the world

that so fascinated the Materialists … in the search for the higher

causes of such precision. Certainly this mathematical precision

underlying all physical reality was not achieved by accident … but had

a much higher cause – some divine force behind it all. It was to

this higher realm that Pythagoras was certain that we needed to direct

our search … in order to better understand reality.4

For more on Pythagoras For more on Pythagoras

2With

Pythagoras actually growing up on the island of Samos just opposite

Miletus, it is even probable that he was once a student of

Anaximander's.

3Orphism

shared many features in common with another worship form found further

to the East: Hinduism. Orphism developed a theology of

reincarnation and transmigration of the souls through endless cycles of

birth, growth, decay and death – in which escape from the grip of this

eternal dance was the desired goal of the Orphic devotee (as with

Hinduism's offshoot, Buddhism).

4Einstein’s

discovery of the shockingly simple mathematical relationship between

all matter and all energy, E=mc2, would have greatly excited

Pythagoras. In fact to call Einstein a mystic would not be inaccurate

at all! He and his scientific friends often engaged in

discussions about the precise nature of the Lord God!

The challenge to unite the Materialist and Mystical cosmologies

Heráclitus

(c. 500 BC) was another Ionian … who certainly had his foundations in

the Ionian Materialist camp but who was also interested in exploring

the higher dynamic behind all reality. As a Materialist, he

concluded that fire was the primordial element of life … even though it

is not a "thing" but merely a life process we are presently

observing. But as something of a Mystic, he also believed that

life is actually a dynamic in which divided forces governing physical

reality are always seeking to recover full unity with the higher order

or Logos from which they were

once separated. Unity with the Logos is thus that higher order or full

reality to which we should ourselves seek to be rejoined. Heráclitus

(c. 500 BC) was another Ionian … who certainly had his foundations in

the Ionian Materialist camp but who was also interested in exploring

the higher dynamic behind all reality. As a Materialist, he

concluded that fire was the primordial element of life … even though it

is not a "thing" but merely a life process we are presently

observing. But as something of a Mystic, he also believed that

life is actually a dynamic in which divided forces governing physical

reality are always seeking to recover full unity with the higher order

or Logos from which they were

once separated. Unity with the Logos is thus that higher order or full

reality to which we should ourselves seek to be rejoined.

Interestingly,

Christians would later identify that same Logos as the dynamic

"Word" of God from which all things in creation were originally derived

… but also a Logos which came to earth in the form of man (Jesus) to

live among us in order to show us the way back to that unity with the

Creator himself, our heavenly Father.

Ultimately

however, the Materialists came to some kind of agreement, thanks to

Empédocles (mid-400s BC), that reality was made up of four elements –

earth, air, fire and water – which combine in different ways to shape

the physical world.

Of

course the Materialists would still find the one most important

question in life to be also the most difficult question to

answer: where did all of this material order come from?

Parménides (early 400s BC) answered the question by affirming that the

question itself was an absurd one … because something could not just

come out of nothing. Reality always is … and has always

been. That thus supposedly answered the question.

But

another Ionian philosopher, Anaxagóras (mid-400s BC) would not stop

with that conclusion. Being from Ionia, he was quite naturally a

Materialist. For instance, he saw the sun as an enormous red-hot

stone … and the moon as merely reflecting the sun's light. But he

had some Mystical instincts as well …holding the view that the Eternal

Mind (the Nous) gave life its beginning … and continued to shape and activate all life.

And very importantly for Athens, he left Ionia and moved to that city

to do his study and teaching … helping to start up Athens as a major

intellectual as well as political center.

Democritus of Abdera (ca. 460-370 B.C.)

the creator of Atomic Theory

Another

Greek Materialist, Demócritus (c. 450-370 BC), would take Greek

philosophy its furthest down the Materialist path. He was widely

recognized even in his own days as a brilliant thinker … who brought to

the ancient Greek world the atomic theory of the cosmos.

Basically, his view was that all life is merely the composite structure

of invisibly minute particles of hard matter: atoms (from the Greek

atomos meaning "not divisible"). These atoms – eternal in their

being – are structured into the more visible material entities we

observe in our world – through the laws of motion – also eternal in

their existence. Another

Greek Materialist, Demócritus (c. 450-370 BC), would take Greek

philosophy its furthest down the Materialist path. He was widely

recognized even in his own days as a brilliant thinker … who brought to

the ancient Greek world the atomic theory of the cosmos.

Basically, his view was that all life is merely the composite structure

of invisibly minute particles of hard matter: atoms (from the Greek

atomos meaning "not divisible"). These atoms – eternal in their

being – are structured into the more visible material entities we

observe in our world – through the laws of motion – also eternal in

their existence.

Democritus was also a profound materialist in his view of human

life. To him life is simply patterns of motion of these soul-less

atoms – operating in accordance with equally soul-less

laws. The human soul itself is simply a brief pattern in

the working of the atoms – a pattern which forms in the human womb,

developing, and then breaking down over a human lifetime … until it

simply ceases to exist when we draw our last breath.

To Democritus there was no such thing as eternal life. Likewise,

God or Divinity was to him simply a construct of human thought – and

had no real existence in the cosmos.

Thus in so many ways Democritus anticipated – by thousands of years –

the direction modern secular science would take in its development with

the modern rise of post-Christian Western culture and society!

For more on Democritus For more on Democritus

Greek Materialists vs. Greek Mystics

|

Greek democracy

The Greeks were also a people given to much thought about the best way to shape, run, and occasionally reform Greek society.

All

Greeks originated as proud tribal peoples, complete with their tribal

assemblies that all men were expected to attend ... for their services

would be frequently called on and it was best that they personally had

"bought into' the social decision, especially on the matter of war, in

order to assure their commitment to the cause. And out of this

experience grew the idea of the people governing themselves. Each

tribe, even when it grew in number and became "civilized" (meaning the

people now lived in cities with temples, commercial buildings,

apartments, town walls, etc.), saw itself as practicing "democracy" –

government (kratos) by the citizens (demos) of the towns or cities themselves.

However

the definition of demos or citizen was not as broad as it is today.

The category "citizen" by no means included all inhabitants of the

city-states but only those males of a recognized tribal pedigree ...

meaning full members by birth of one or another of the old tribes

originally making up the community. Foreigners or xenoi living in the

cities – which often included a huge number of the industrial or

commercial workers (and certainly also the many slaves) – were actually

quite numerous in Greek culture. These individuals did not qualify for

democratic privileges ... even if they were descendants of several

generations of xenoi living and working in these "democratic"

city-states.

Athenians and Spartans.

Leading the way in this democratic development was the city-state of

Athens. But the path by which Athenian democracy would develop was

very, very stormy ... just as was the rise to political prominence of

Athens itself.

During most of Greece's Archaic Period the Spartans had been considered the dominant political power or hegemon

in Greece. But during the 500s BC Athens, which was well positioned at

the center of this huge Greek world, and possessing a number of natural

advantages (a very strong citadel, a wide fertile region surrounding

it, and closeness to the sea), soon rose to its own prominence. Also,

having the strongest navy of all the Greek city states (thanks to its

political leader Thucydides), Athens was early looked to in order to

provide leadership in organizing the city states into a great Greek

navy, one designed to keep the Persians away from Greek shores. But

the Athenians proved themselves as well on land as foot soldiers.

Thus

Greek leadership was divided between — and often competed for — by both

Sparta and Athens (Corinth and Thebes were also powerful, though only

at a secondary level).

Athens' struggle to secure

democracy

But

Athens was wracked by internal problems. Athens' rich and powerful

aristocracy, long used to dominating Athens' political and economic

life from its political council, the Areopagus, found itself

increasingly challenged by the Athenian commoners (not really all that

common, since they still occupied a much higher status than the more

numerous xenoi ("foreigners") in Athens and the even more numerous

slave portion of the Athenian population).

The

aristocrats first attempted to control Athens' affairs with a very

tough legal code or constitution (in which the penalty for a wide range

of offenses was death) laid down by Draco (ca. 620 BC) – and thus very

"Draconian" – which, though an improvement over the older oral laws and

traditions, still did not satisfy the political desires of the

commoners. However his constitution did provide for the creation of a

Council of Four Hundred, its members drawn from the commoners by lot.

A generation later, in the early 500s BC, another aristocrat, Solon,

serving as archon (one of several leaders governing Athens), was

commissioned to reform this constitution. He attempted to find a

compromise between the contending social classes by ranking the

citizens into four classes and giving each of them a certain number of

economic and political duties and rights. But soon after his departure

from power, class rivalries gradually returned. Peisistratus, a nephew

of Solon, seized power on behalf of the poorer citizens, thus becoming

"tyrant," actually meaning at the time "champion of the poor." His

political base was never secure and he was in power – and exiled –

frequently from 546 to 527 BC as political confusion continued to grip

Athens. A generation later, in the early 500s BC, another aristocrat, Solon,

serving as archon (one of several leaders governing Athens), was

commissioned to reform this constitution. He attempted to find a

compromise between the contending social classes by ranking the

citizens into four classes and giving each of them a certain number of

economic and political duties and rights. But soon after his departure

from power, class rivalries gradually returned. Peisistratus, a nephew

of Solon, seized power on behalf of the poorer citizens, thus becoming

"tyrant," actually meaning at the time "champion of the poor." His

political base was never secure and he was in power – and exiled –

frequently from 546 to 527 BC as political confusion continued to grip

Athens.

Eventually

a compromise was achieved (509 BC) – in no small part due to the need

to secure unity in the face of the political threat posed by both

Sparta and Persia. A popular politician named Cleisthenes

was elevated to power to reform the constitution. He reorganized the

tribal basis of Athenian citizenship from four to ten tribes –

membership based no longer on class but on residence in the city. From

these tribes were drawn (by lot) members of the all-important

legislative and judicial councils. He saw this not so much as

"democracy" as isonomia: full legal equality of all (male) citizens. Eventually

a compromise was achieved (509 BC) – in no small part due to the need

to secure unity in the face of the political threat posed by both

Sparta and Persia. A popular politician named Cleisthenes

was elevated to power to reform the constitution. He reorganized the

tribal basis of Athenian citizenship from four to ten tribes –

membership based no longer on class but on residence in the city. From

these tribes were drawn (by lot) members of the all-important

legislative and judicial councils. He saw this not so much as

"democracy" as isonomia: full legal equality of all (male) citizens.

The challenge of the Persian Wars

In

the latter part of the 500s BC, just as a number of Greek towns were

beginning to grow in power as "city-states," the Persians surprised the

world by conquering Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt … and Greek Ionia.

Thus was the mighty Persian Empire born. This was the first time

ever that nearly the whole of the Near East had been brought under a

single rule.

Some

of the Greeks living in Ionia did not particularly take well to this

Persian domination (though others did, even serving in the Persian

military) and rose up in revolt against Persian rule in the 490s

BC. The citizens of Athens were quick to back the Ionian rebels –

who, however, were eventually forced back under Persian rule.

This

action of Athens and other Greek city-states in supporting the Greek

Ionian rebellion drew the wrath of Persia … and led to a Persian desire

to crush any further Athenian or other Greek "meddling" in Persian

affairs. Thus the Persian Greek wars began.

This

Persian response to Greek "meddling" in turn forced the two leading

Greek city-states, Sparta and Athens, into cooperation (in fact forcing

a general Greek unity among all the Greek cities that had previously

been lacking).

The Battle of Marathon (490 BC).

Quite surprisingly (to the Persians, anyway!), in a number of major

encounters, the Greeks succeeded in defeating the Persian armies and

navy sent to Greece, thus not only helping to secure Greek freedom, but

elevating Greece – and in particular Athens – to a new status

politically.

In the first encounter, Athenian hoplites (troops) were able to

surround, attack directly, and completely rout the Persian troops that

had just arrived by sea at the Greek coast at Marathon (the Spartans

were no help in this engagement, claiming to be deeply involved in a

religious ceremony at the time). The Persian survivors (they lost over

6,000 troops, in contrast to Athens' loss of 190 troops) retreated to

Asia, where they prepared themselves for a second attempt.

However, a revolt in Egypt against Persian domination delayed that

second attempt.

The

Persian king Xerxes, who took over when his father died in 486 BC, was

as dedicated to the reduction of Greece, and the total destruction of

Athens. After having crushed the Egyptian revolt, and after

three-years of military preparation, Xerxes was finally ready to

undertake just such a mission. However, Sparta now joined Athens

in the effort to fend off the Persians. But most of the other

Greek city-states still chose to stay out of the action.

Setbacks at Thermopylae and Artemisium (480 BC).

The Persians now approached Greece both by land and by sea, with the

first encounter taking place at a narrow pass at Thermopylae, along the

eastern coastal road in Thessaly (northern Greece). A small group

of Spartan-led troops were able for three days to hold off the invading

Persians, before a Greek traitor showed the Persians a path around the

pass, and the Greek troops were ultimately surrounded and slaughtered

there.

At

the same time the Athenian-led Greek fleet managed to fight off the

Persian fleet at Artemisium, until news of the Greek defeat broke the

Greek spirit and the Greek fleet withdrew to Salamis. The

Persians then continued their advance through Greece, destroying

city-state after city-state as they went, including the city of Athens

as well.

The battles at Salamis (480 BC) ... and Plataea and Mycale (479 BC). But the

Persians were blocked at the narrow isthmus that opens the huge

Peloponnesian peninsula to the rest of Greece, and thus Xerxes decided

that a victory at sea would be required to finish off the Greek

resistance. But under the brilliant leadership of the Athenian

general Themistocles, the Greek navy was able to gain a very decisive

victory at Salamis over the Persian navy.

The

next year, Xerxes was ready to try again to conquer Greece, and sent

his troops to Greece, where they assembled at Plataea. A battle

which then took place there did not go well for the Persians, who lost

their commanding general and then found their camp surrounded, and

ultimately destroyed by the Greek hoplites. At the same time,

another sea battle – at Mycale – did not go well for the Persian fleet,

making the Persian defeat even more obvious.

These were horrible setbacks for the Persians, ones they would never recover from – at least in their dealings with the Greeks.

Yet

for the Greeks it proved to be a major turning point in the history not

only of Greece but even of Western civilization itself. From this

point on, Greece, led most importantly by Athens, would leave a deep

political, social, intellectual and moral impact on Western

civilization … one that would shape that civilization not only in the

many centuries of Greek political and cultural greatness, but even down

to today, where that same legacy is built deeply into the ways of the

West.

|

|

The Golden Age of "Periclean

Athens" (and Greece)

The Delian League.

By the mid-400s BC Athens was the dominant sea power in Greece, Sparta

the dominant land power. But the sea was the more important

element in Greek life at that time – and thus Athens naturally tended

to dominate Greek affairs. In fact, although the Persians had

been twice defeated by the Greeks, their shadow continued to loom over

Greek thinking – and thus Greek defenses stood always at the ready,

headed up primarily by Athens which had organized a number of Greek

cities into a defense organization known as the Delian League.

"Periclean Athens." The fact that the Greeks had escaped Persian rule was to become important in the future development of

Greece. Spurred on by the continuing threat of Persia, Greece

developed its own strength, especially under the leadership (even

dominance) of Athens. Athens, after the two grand defeats of the

Persians at Salamis and Plataea, soon became the center of a newly

rising Greek civilization, with Athens itself reaching the height of

its power and glory about 450 BC, roughly the time of the political

leader Pericles (490-429 BC). "Periclean Athens." The fact that the Greeks had escaped Persian rule was to become important in the future development of

Greece. Spurred on by the continuing threat of Persia, Greece

developed its own strength, especially under the leadership (even

dominance) of Athens. Athens, after the two grand defeats of the

Persians at Salamis and Plataea, soon became the center of a newly

rising Greek civilization, with Athens itself reaching the height of

its power and glory about 450 BC, roughly the time of the political

leader Pericles (490-429 BC).

Pericles was born to a highly-placed noble Athenian family … and

followed in his father's footsteps to command the Athenian military in

some of its most important engagements – most notably those conducted

during the First Peloponnesian Wars of Athens versus Sparta in the

period 460-445 BC. Pericles was also a very close friend of the

philosopher Anaxagoras. And Pericles became very active in the

world of politics, becoming the primary prosecutor against the

politician Cimon, who had succeeded in having the great general

Themistocles (a warrior that Pericles greatly admired) expelled or

"ostracized" from Athens. Pericles eventually was indeed able to

have Cimon himself ostracized.

Pericles was a practitioner of "democratic" politics … doing what he

could to use state resources to support the poor – winning obvious

favor from that huge sector of the population. Indeed, he

identified himself as a champion of the little people (tyrant). And he

also limited voting rights to only those Athenians with both parents

being Athenian citizens … so as to keep the voting privileges enjoyed

by even the poorest Athenians from being diluted by the massive

entrance of the foreigners or xenoi into the ranks of Athenian

citizenship.

This all seemed to support the idea that indeed, Athens was a very

grand city … everyone (at least its citizens) able to afford the

pleasures of a highly successful society.

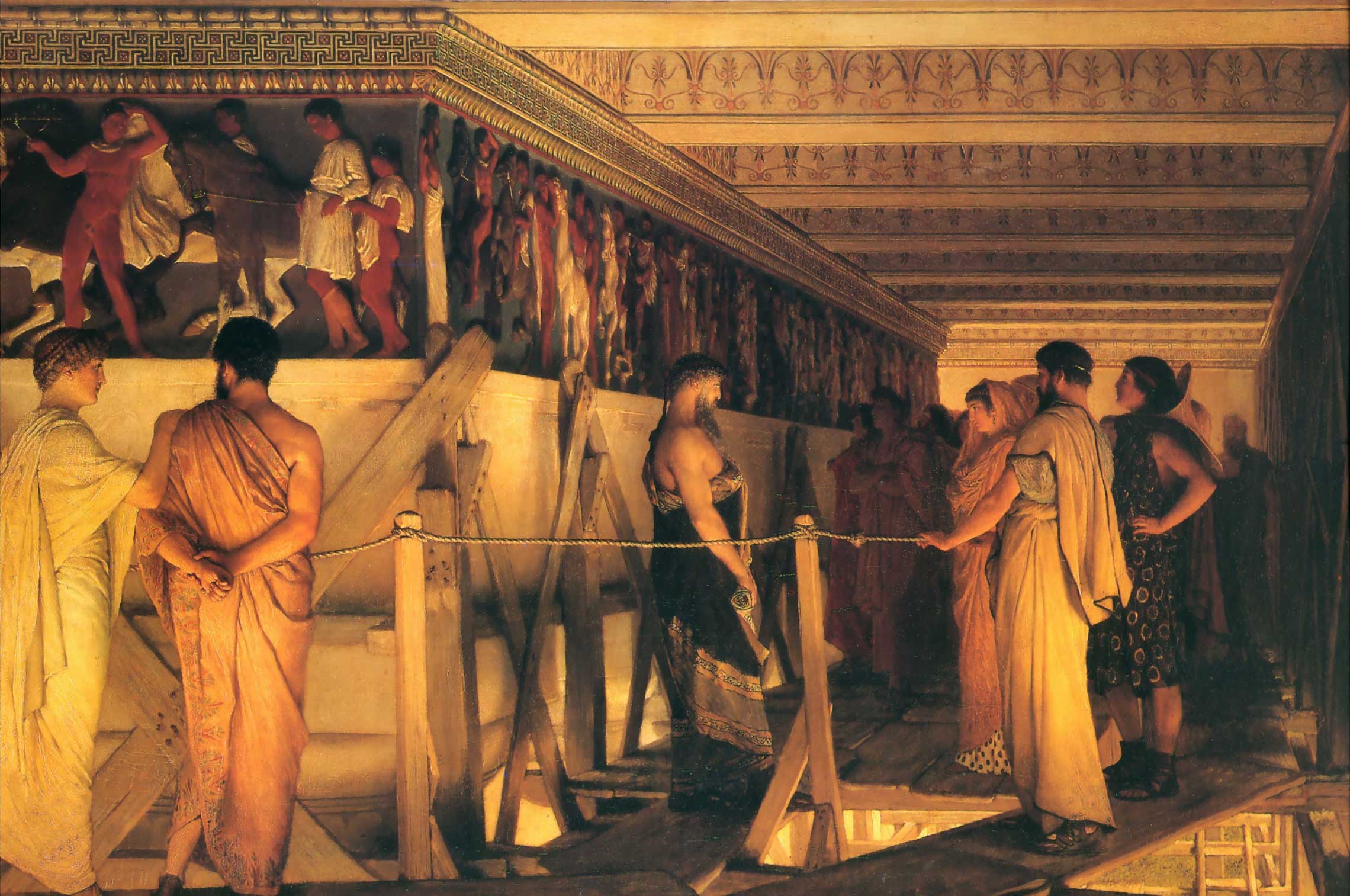

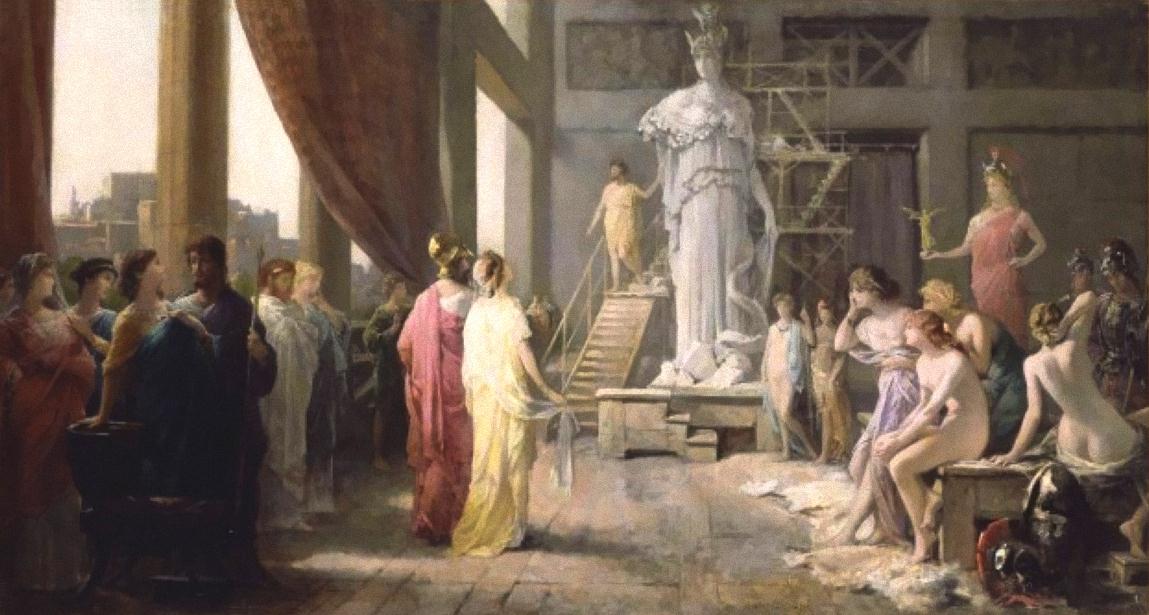

Athens' great cultural achievements.

And yes, indeed, the mid-400s marks the grand age of Athens.

Athens' democracy and the leadership of the very capable

general/statesman Pericles combined to offer Athens' citizens a very

rich life. A lavish building program turned the city into an

architectural marvel. And the tendency of Greece's finest minds

to gravitate to Athens made it "the school of Greece."

|

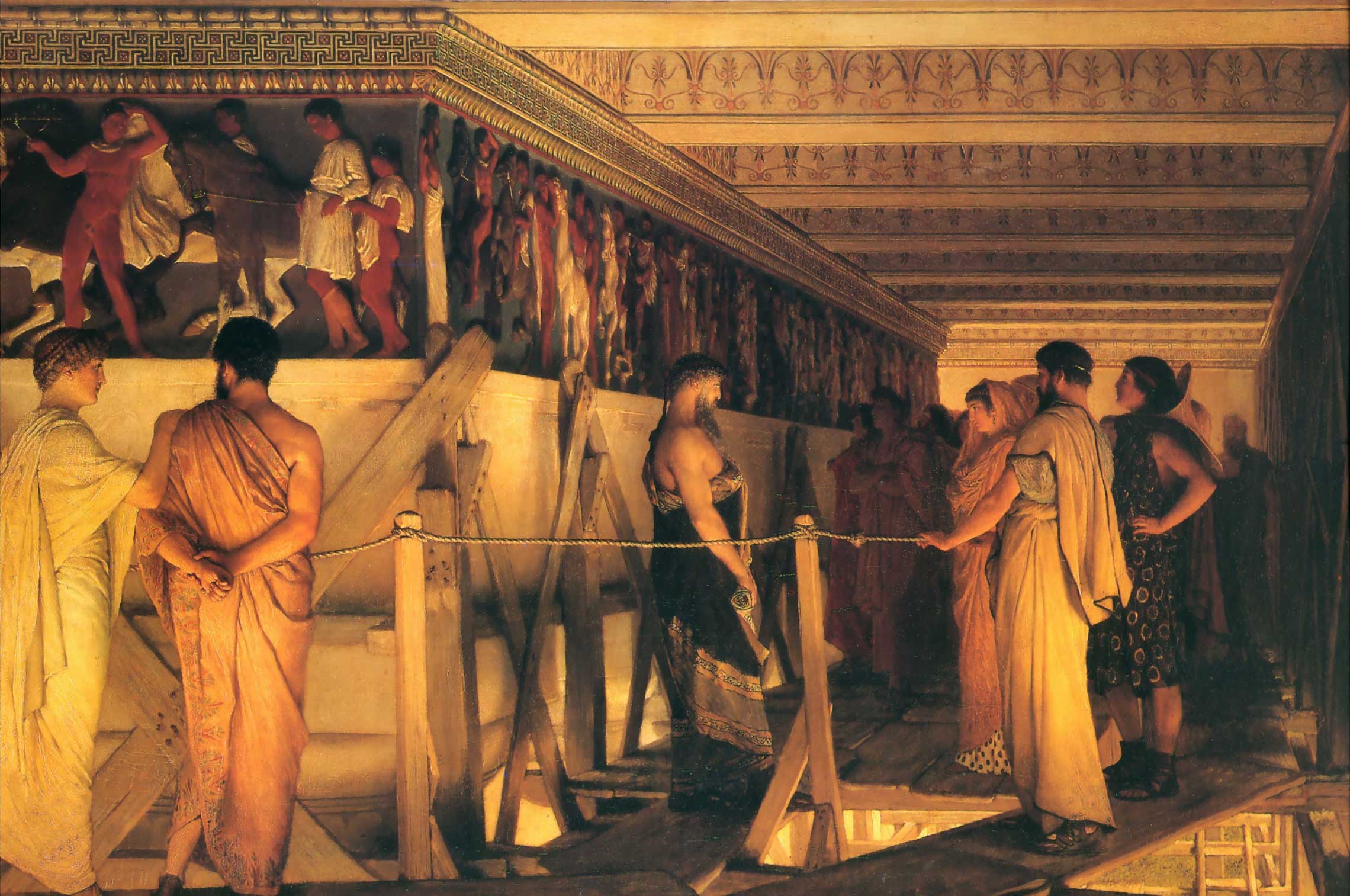

Phidias showing the freize of the Parthenon to his friends - by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1868)

Birmingham (England) Museun and Art Gallery

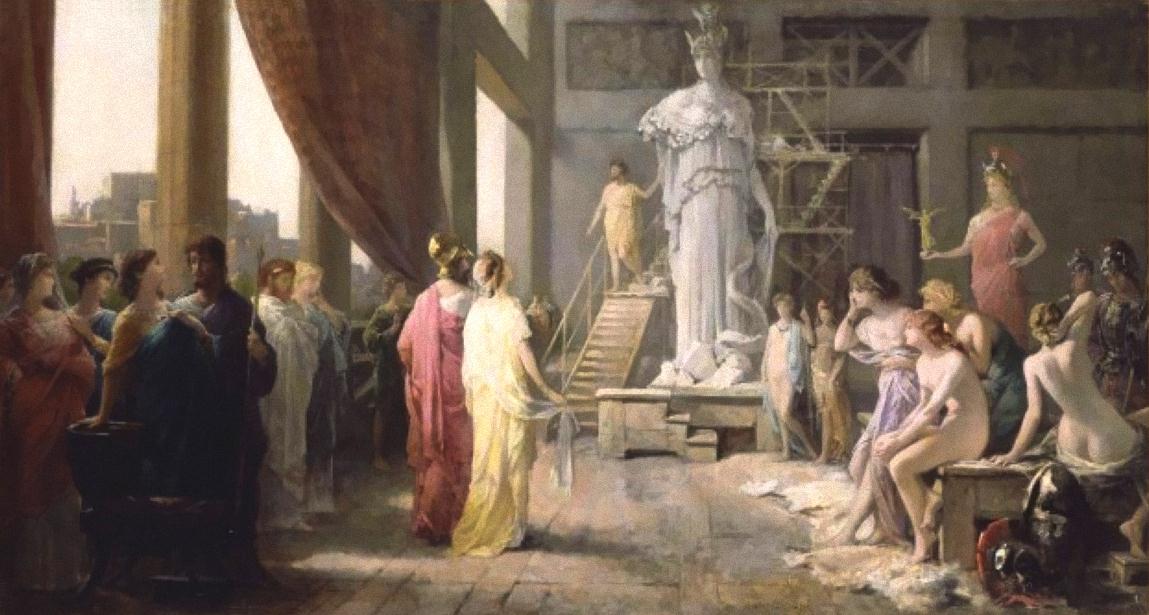

Pericles and Aspasia in Phidias' studio admiring his statue of Athena - by Hector Leroux

Athens - with the Acropolis

in the distance

Miles Hodges

The front of the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The front of the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The entrance to the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Athena-Nike Temple on

the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Propylaea Temple on the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Erectheum Temple on the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Erectheum Temple on the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

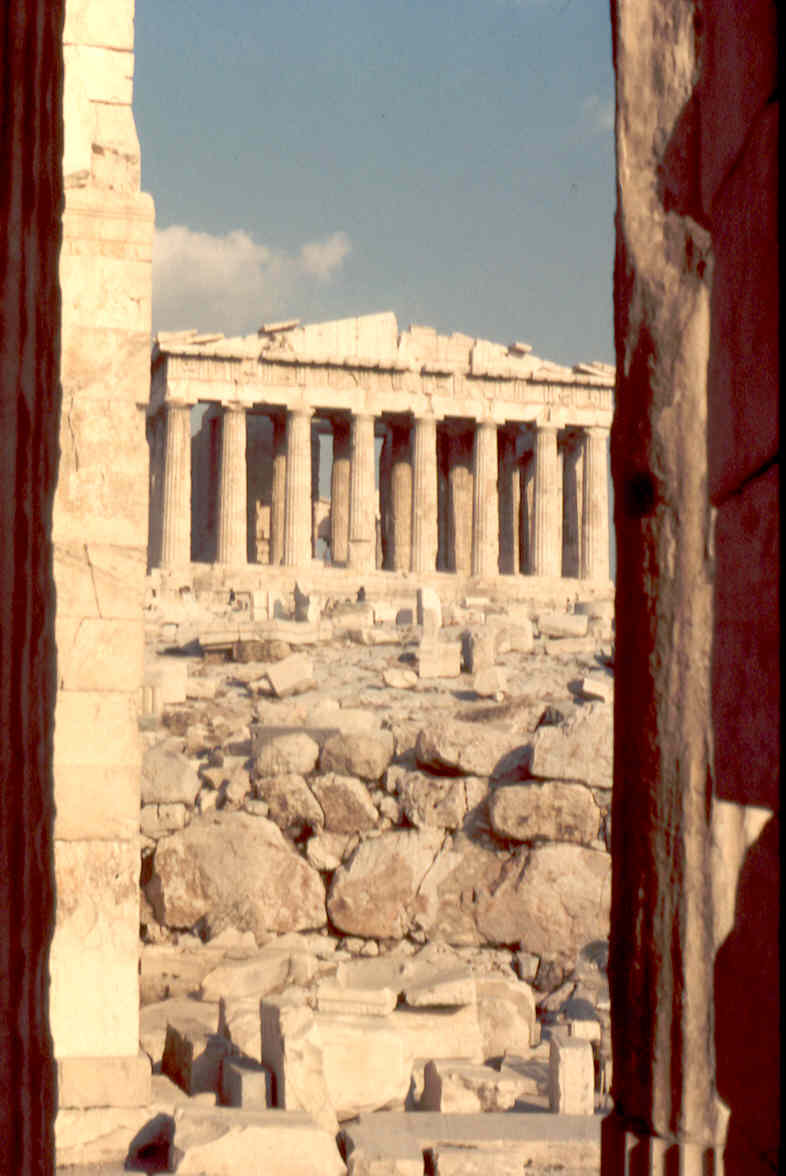

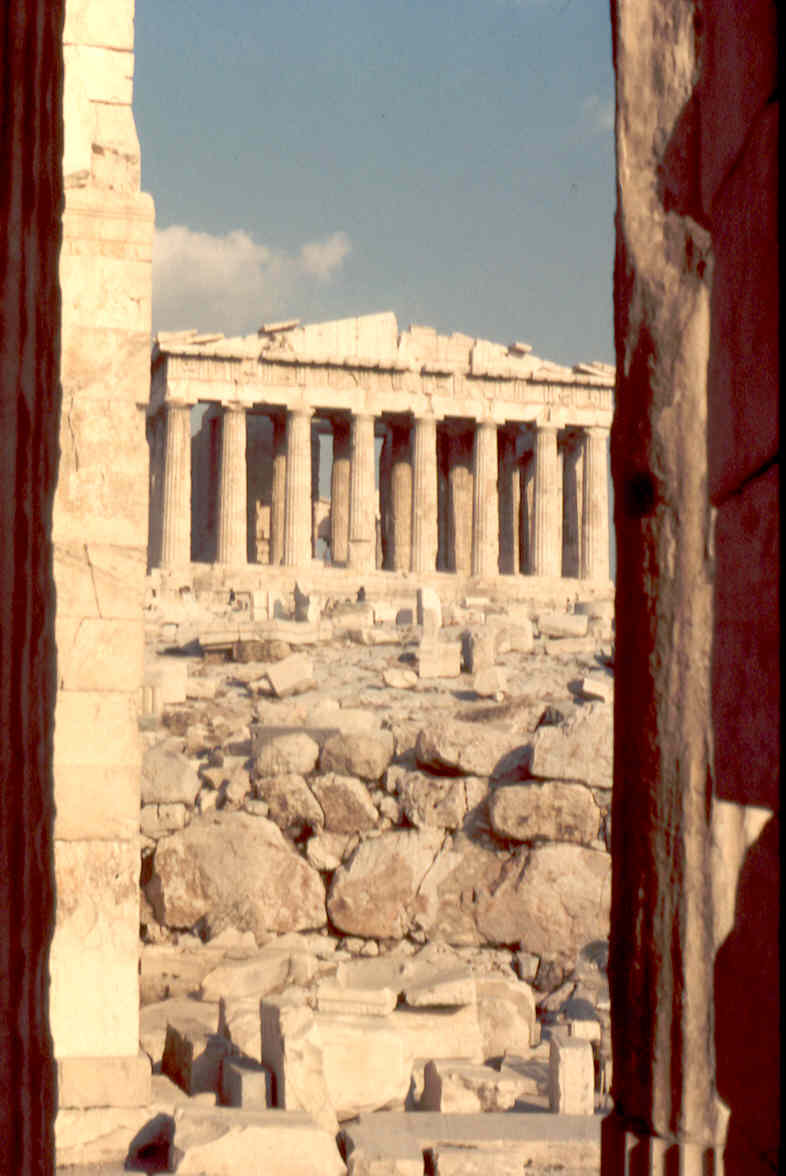

A view of the Parthenon on

the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Parthenon Temple atop

the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

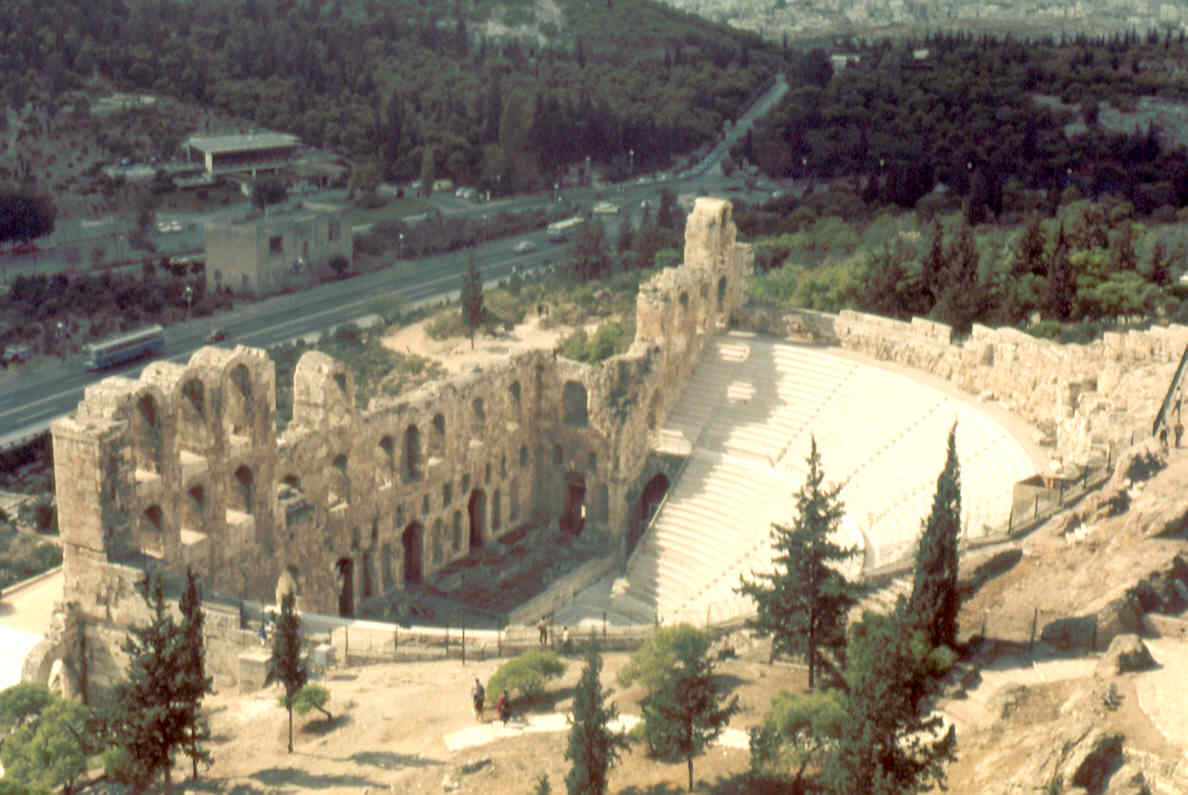

The Dionysian Theater – viewed

from the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

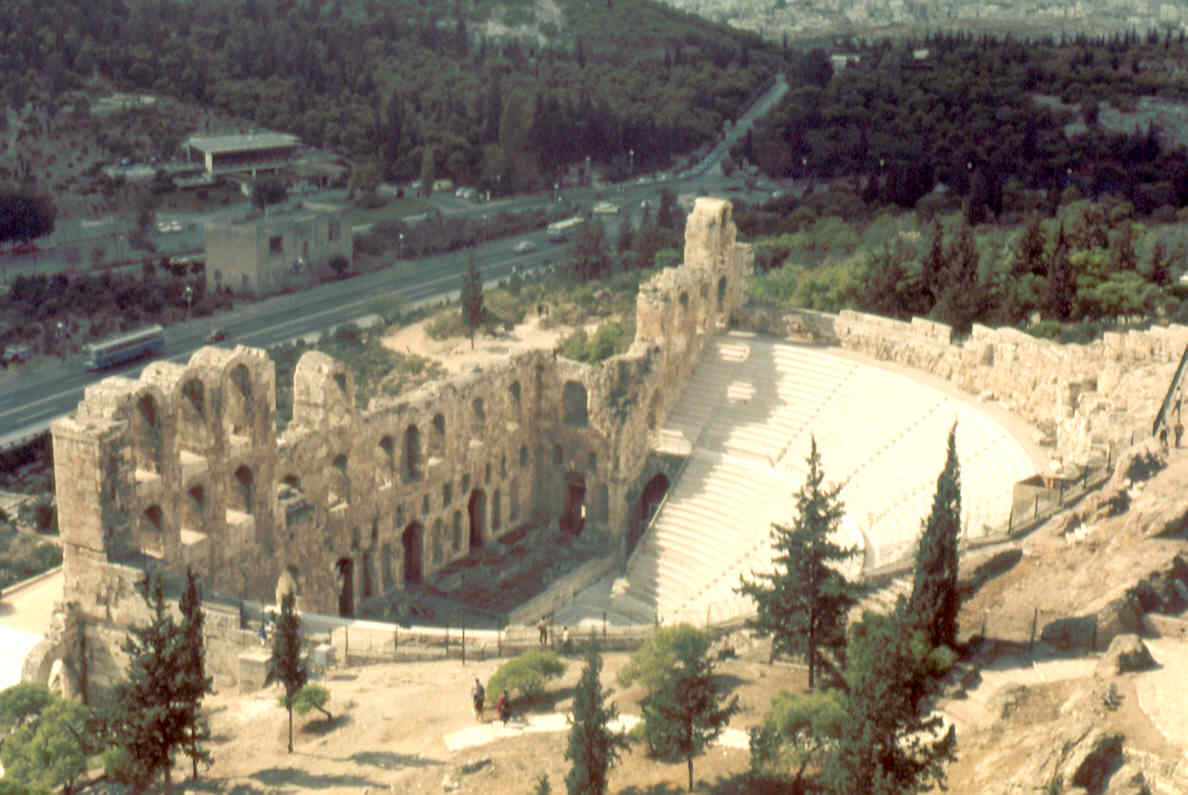

The Theater of Herod Atticus – viewed from the Acropolis

Miles

Hodges

Other Greek communities Sparta

Foundation walls of

Sparta

Miles Hodges

Foundation walls of

Sparta

Miles

Hodges

Olympia

Ruins of ancient

Olympia

Miles Hodges

Ruins of ancient

Olympia

Miles Hodges

Ruins of ancient

Olympia

Miles Hodges

Reconstructed stadium at

Olympia

Miles

Hodges

ATHENS' POLITICAL-SOCIAL-MORAL DECLINE |

|

Athenian democracy under challenge

Actually,

Athenian democracy was more an attitude than a political institution or

policy. The commoners were jealous of their political rights and

quick to defend them against any appearance of usurpation from any

source. Tragically, this "democratic" attitude was easily molded

by the shapers of "popular opinion" – by the political satire of the

popular theaters of Athens ... and by the political maneuvering of

clever speakers in the Athenian Assembly, in particular by the Sophists

and their wealthy disciples – sort of the ancient version of modern day

trial lawyers, who specialized in playing on the prejudices and fears

of the people in order to whip up this or that popular mood ... which

they skillfully directed according to their own personal ambitions.

The Sophists.

As

the Athenians' public life in the middle and second half of the 400s BC

developed in its richness and importance, wealthy families hired tutors

for their sons in order to prepare them for leadership roles in the

public assemblies. This was where the laws guiding Athens would

be shaped. This was where economic, diplomatic and military

decisions that were key to the well-being of the community would be

made. They wanted their sons to become persuasive in their

rhetoric, quick in public debate and noble in their public bearing – so

that they would find themselves at the heart of the doings of these

public assemblies.

A particular class of wise ones or "Sophists" (Greek sophia

= "wisdom") gladly offered their teaching services for a fee to these

families. They built their learning or wisdom around the need to

produce practical results in the form of skilled or adept students. These

Sophists were sort of the ancient version of modern-day trial lawyers, who

specialized in using very clever and highly persuasive "rational"

arguments in order to win their cases. As demagogues, they proved highly skillful in cultivating the prejudices and fears of the people … to whip up this or that

popular mood.

As for the higher issues of life such as truth, goodness, justice,

etc., in general the Sophists tended to be agnostic – that is, they

professed to have no knowledge about (or even concern for) such

ultimate or transcendent things. Indeed, they functioned as if

such things did not really matter in the course of actual

existence. Success was measured not in possessing the knowledge

of ultimate truth, but in knowing how to use truths (or "truthiness" as

it is sometimes termed today) for personal political and economic gain.

Democratic cruelty

Ostracism. At the same time that wealthy Athenian

families were very busy in creating something of a newly-rising ruling

class of "more enlightened" individuals, at the level of the lower

social orders tendencies were also developing that would serve to

weaken further the moral foundations of Greek democracy.

One of these tendencies was the long-standing practice of "ostracism"

or the exiling of Athenians by their fellow citizens, because for one

reason or another they had fallen out of popular favor. At a

special general assembly, citizens were invited (usually by these

Sophist-trained demagogues) to record the name of a person they might

want exiled on a broken piece of pottery and deposit it in urns.

These pottery shards or ostraka were then tallied by a public

official. The person receiving the most votes (although at least

a minimum of 6,000 votes) was "ostracized" and thus automatically

exiled for ten years.

Themistocles is ostracized. In 472 or 471 BC the Athenian general Themistocles … who had been one

of the Athenian commanders at the Battle of Marathon, who then led the

Athenians to develop massive sea power and subsequently devised the

scheme to trap and destroy the Persian navy at Salamis, and who was the

leading political figure over the next ten years … was brought before

the ever-suspicious Athenian Assembly – fed by rumors coming from the

Spartans of a role in a political conspiracy (entirely false in fact,

designed cleverly by the Spartans to destroy their rival Themistocles)

– and adjudged by the Athenian commoners to be guilty of the crime of

arrogance. He was thus was ostracized. He fled to Macedonia

– then moved on to Ionia … where the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes offered

to bring him into Persian service as a regional governor! Themistocles is ostracized. In 472 or 471 BC the Athenian general Themistocles … who had been one

of the Athenian commanders at the Battle of Marathon, who then led the

Athenians to develop massive sea power and subsequently devised the

scheme to trap and destroy the Persian navy at Salamis, and who was the

leading political figure over the next ten years … was brought before

the ever-suspicious Athenian Assembly – fed by rumors coming from the

Spartans of a role in a political conspiracy (entirely false in fact,

designed cleverly by the Spartans to destroy their rival Themistocles)

– and adjudged by the Athenian commoners to be guilty of the crime of

arrogance. He was thus was ostracized. He fled to Macedonia

– then moved on to Ionia … where the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes offered

to bring him into Persian service as a regional governor!

Tragically for Athens itself, it would take some time and distance from

this sad episode before the Athenians would recognize the cruelty that

they had delivered to the one man … who not only saved Athens from

Persian destruction, but put the Greeks on the path to greatness.

Athenian arrogance / Athenian imperialism

Another (and similar) major problem facing the Athenian democracy would

be the arrogant attitude it came to assume with respect to its fellow

Greek city states – and the resentment this would breed among these

other Greeks. At this point Athens no longer was led by wise men

with a deep sense of high-minded virtue, but by cynical, manipulative,

self-serving politicians, setting a similar moral tone for the entire

Athenian community.

With the passing of time, as the Persian threat seemed to dwindle – but

Athenian collection of dues from its allies for "defense" purposes

continued nonetheless – resentment by members of the Delian League

against Athens grew, especially when it became obvious that this money

the other cities were sending to Athens had little to do with Greek

defenses and more to do with a lavish Athenian building program going

on during Athens' "glory days." Consequently, Athens' Greek

allies in the Delian League felt as if they had been seduced into

surrendering their independence to a growing Athenian Empire.

Certainly also, the money they were sending Athens could have been used

to improve their own cities. Anger against Athens began to grow

among the other Greek city-states.

Sparta, the major rival to Athenian power, with its well-disciplined

land army, was quick to take advantage of this discontent and organized

a rebellion against Athens in 431 BC. Also Thebes, seeing the

growing mood of Greek rebellion against Athens, decided to make a bid

for dominance in Greek affairs.

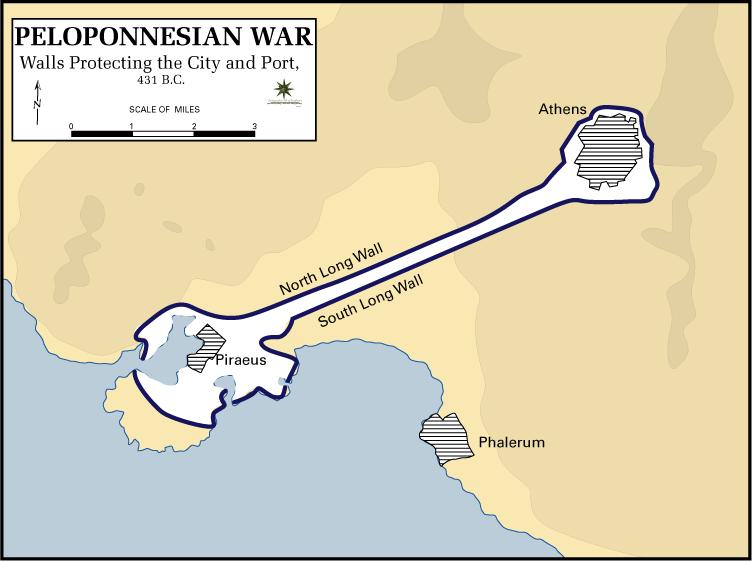

The Peloponnesian Wars, and the decline of Athens.

Thus wars (the "Peloponnesian Wars") broke out in Greece (431-421 BC;

421-404 BC; 395-378 BC), wars that tended to ravage Greece – yet seemed

to resolve nothing. The worst of these were the engagements

between 431 and 404 BC. Truces would be declared only to have one

party or another decide that it was advantageous to break those

treaties and start up a new round of wars. Also political leaders

played treacherous games of shifting their loyalties according to their

personal advantage.

Pericles' efforts to keep Athenian spirits high.

For a while the great general and Athenian political leader Pericles

was able to keep Athenian spirits high as it struggled with the

hostility of the surrounding Greek world. But Athens had taken on

a war that would drain it economically and spiritually … and offer no

gain whatsoever in return. Consequently, Athens found itself

bleeding to death economically and spiritually.

Decline.

Thus things went quickly downhill for Athens. A long-lasting

siege of Athens by Sparta created devastating conditions within Athens,

taking the lives of many Athenians, including Pericles (429 BC).

Athens' new leader Alcibiades

(Pericles' nephew) proved to be largely a disaster for Athens, as he

led Athens on ruinous expeditions and switched loyalties constantly ...

including even siding with Athens' enemies, first Sparta (415-412 BC)

and then Persia (412-411 BC) during his cynical political career! Decline.

Thus things went quickly downhill for Athens. A long-lasting

siege of Athens by Sparta created devastating conditions within Athens,

taking the lives of many Athenians, including Pericles (429 BC).

Athens' new leader Alcibiades

(Pericles' nephew) proved to be largely a disaster for Athens, as he

led Athens on ruinous expeditions and switched loyalties constantly ...

including even siding with Athens' enemies, first Sparta (415-412 BC)

and then Persia (412-411 BC) during his cynical political career!

Ruin. The war

gradually led not only Athens but also much of the rest of Greece to

ruin. Finally, in 405 BC, the Spartans (now allied with the

Persians) defeated Athens even at sea – and Athens was forced into a

humiliating surrender, forced to tear down her town walls, surrender

her fleet and give up all her overseas possessions. Only Sparta's

compassion prevented Corinth and Thebes from getting their wish to

level all of Athens and also enslave the entire Athenian population.

Socrates is condemned to death.

Even more tragically, the West's most famous philosopher, Socrates –

who was loudly critical of the amoral antics of the Sophists – would

eventually (late 400s BC) become the object of the satire of the

playwrights (notably Aristophanes) and the demagoguery of the Assembly

speakers. Both groups turned the public against him.

In 399 BC the Assembly voted for Socrates' death ... given somewhat

honorably in that he was to inflict this punishment on himself (poison,

usually). Actually, they expected Socrates to do what most

Athenians did when the Assembly turned against them: flee Athens.

This was certainly the counsel of Socrates's devoted disciples.

But Socrates reasoned that to flee would be to discredit the very

truths and moral principles to which he had dedicated his life in his

teachings. Thus he took the poisonous hemlock and died,

surrounded by his disciples.

Socrates's death by the decision of Athens' democratic Assembly

consequently caused democracy to be intensely distrusted by some

(Socrates' famous student Plato, for instance) or at least not highly

regarded (Plato's equally famous student Aristotle, for instance).

|

THE "BIG THREE": SOCRATES, PLATO, AND ARISTOTLE |

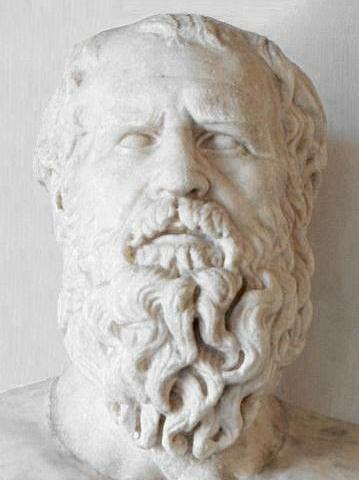

Socrates

is known largely through Plato's heroized representation of him.

We know that subjects such as social ethics or public morality were of

great interest to him – though he was also interested in such subjects

as justice, beauty, goodness, and even physics and metaphysics.

Above all, he was interested in conveying to his students the

understanding of how to live a life of honor and truth … particularly

in service to the larger social order. Socrates

is known largely through Plato's heroized representation of him.

We know that subjects such as social ethics or public morality were of

great interest to him – though he was also interested in such subjects

as justice, beauty, goodness, and even physics and metaphysics.

Above all, he was interested in conveying to his students the

understanding of how to live a life of honor and truth … particularly

in service to the larger social order.

He was keenly aware that objective reality and what our minds

understand of reality are separated by a great mental divide (the

general consensus of Greek philosophy by that time). But to the

optimistic Socrates, rational inquiry, meticulously but humbly pursued

(his dialectical method), could close this divide. In using rational

methods of inquiry, human mind and soul could be brought to discover

transcendent (thus absolute) truth and goodness – and personal

happiness.

Socrates felt optimistically that knowing the truly good would

necessarily direct a person to act in line with this knowledge.

Also, the quest for such knowledge was the very heart of life itself –

its highest form (almost a divine enterprise).

Unfortunately, the Athenians proved not to be so enlightened by the

truth as he had hoped, and ordered him to poison himself … for

"teaching the youth not to reverence the gods" (something actually not

the case at all).

For more on Socrates For more on Socrates

|

The death of Socrates - by Jacques-Louis David (1787)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

|

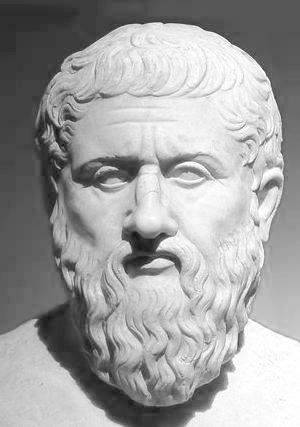

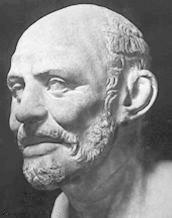

Socrates's student Plato (427-347 BC)

The realm of the Ideon. These perfections were idealized Forms or Ideas (Ideon or Eidei

– terms he used interchangeably) like geometric forms that describe

life ideally. But though these Forms existed only as ideas, they

were more real than the visible world around us. But how could

Plato be so sure that these Forms we had never ever seen were so real?

His thinking went something like this. We know, for instance, that

there are no perfect circles to be found anywhere in nature. Some

things in nature only tend toward a perfect circular form and thus may

be called circular. But how is it that we know that they are not

perfectly circular? Only because for some strange reason our minds can

indeed hold clearly a distinct understanding of a perfect circle –

though we have never seen such anywhere in the world around us.

We can thus make such assertions about circularity – not because we

have seen perfect circles, but because we certainly hold the idea of a

circle clearly in our mind. If we could not conceive of such perfect

ideas in our minds, then we would not be able to think clearly or

rationally. The fact that we can think about circles, to Plato proved

their existence. This existence, of course, was not in the immediate

world around us, but in some mysterious realm of higher being or

thinking.

Plato was interested in uncovering this perfect world of the Ideon or

Forms – in bringing it to light to human understanding. Indeed,

this was to Plato (and by many "Platonists" who came after him) a

religious enterprise – not just a matter of detached scholarship.

Plato and the realm of politics.

With regard to the world of politics, most understandably, after what

the Athenian Assembly did to his teacher Socrates, Plato was no lover

of democracy. But Plato did believe that there existed part of

the realm of the Ideon ... able to guide our shaping of an ideal

state. In his Republic, Plato described that ideal state as one

that was divided by classes or castes into three levels of

society: workers, guardians (soldiers) and governors

("philosopher kings").

Tragically, when later in life Plato was called to Syracuse (Greek

Sicily) by Dion (a former student of Plato's) to help Dion's young but

dissolute nephew Dionysius II become just that "philosopher king" and

put such an Ideal State into effect, the whole thing ended up most

disastrously. Dionysius's older brother-in-law Dionysius the

Elder, who was actually ruling Syracuse at the time, was deeply

irritated by Plato's disdain of his attempts at being a popular tyrant

… and had Plato arrested. Plato was spared death only by being

sold into slavery … from which a friend of Plato's went on to purchase

his freedom. Oddly enough, when Dionysius the Elder died, Plato

was invited back by Dion to Syracuse to try again with the young

Dionysius. But Dionysius fought with his uncle Dion, and had him

expelled … but forced Plato to stay on. Plato was finally able to

get out of Syracuse. Ultimately the "philosopher king" Dionysius

found himself facing a popular uprising … in which he was ultimately

driven from power.

What Plato actually learned from all this very non-Idealist experience

in the realm of politics is not known to us today. Nothing in

Plato's writings points to any kind of development of his political

thinking because of this sad experience.

Apology

Republic

Laws

Statesman

Crito

Critias

Gorgias

Meno

Parmenides

Phaedo

Phaedrus

Sophist

Symposium

Theaetetus

Timaeus  For more on Plato For more on Plato

|

Raphael's School of Athens

At the center, Plato pointing upward to the heavens; Aristotle pointing downwards to the earth ...

a keen depiction of the essential philosophical difference distinguishing the two!

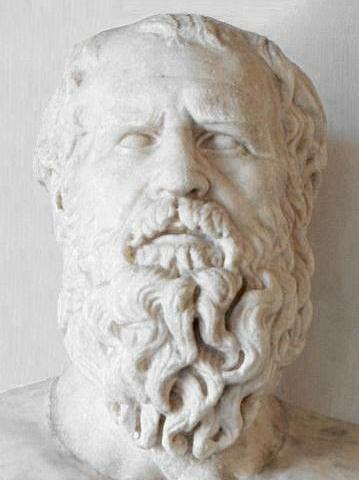

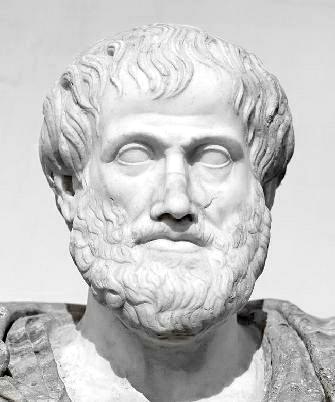

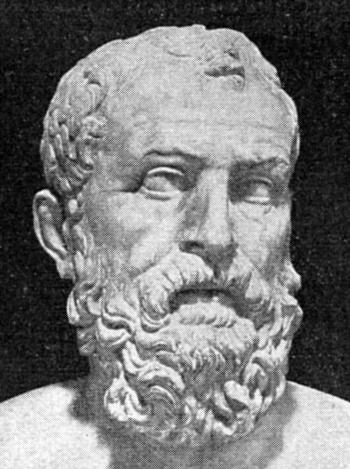

Aristotle (384-322 BC)

Aristotle went in a direction opposite that of his teacher,

Plato. While Plato focused his attention on the mysterious world

of the perfect Forms, Aristotle focused his attention on the messier

visible world immediately around him. Aristotle was greatly fascinated

by this empirical or physical world. He was looking for Plato's

Forms actually contained within this visible world.

But Aristotle eventually surmised that these Forms were merely

abstractions in our mind which we use to categorize the immense

information that comes to us about the surrounding world. These Forms,

though useful to human logic, were themselves only mental constructs or

kategoriai (categories)

… useful to the human mind in developing an organized understanding of

how to understand and work with the surrounding world. "Dog," or

"barn", or "hot", or the color "red" were just such categories.

They had no separate existence like gods or defining spirits (as Plato

had asserted).

But Aristotle was deeply interested in exploring this world of

categories, trying to discover as many different categories as possible

… in all fields of life, from biology to geology, but also in the realm

of logic, ethics, and politics.

As already mentioned, in the field of politics, he was not particularly

interested in one or another particular category of social

organization, whether a society governed by a single person, or a few,

or even the many. What he understood as the "good society" was

one which – whatever the specific form – was carefully ordered by a set

of very strong moral foundations … ones that human cleverness would not

be able to manipulate – but which would offer clear guidance to that

society as it took on life's various challenges. He made this

very clear in his famous publication, Politics.

Most interestingly however, when it came to discussion of things beyond

this earthly realm – the heavenly realm of the sun, moon and stars –

Aristotle evidenced a religious awe. Though the earth might be marked

with physical imperfections, these heavenly bodies were the essence of

the divine, for they were perfect – perfect in their circular shape and

circular movement. Thus for Aristotle the perfect-imperfect

dualism in life occurred not between things seen and unseen (as it had

for Plato), but between the imperfect things seen on earth and the

perfect things seen in the heavens.

Thus even in his religion, Aristotle remained focused on the visible

universe around him. "Heaven" was not a place found beyond the

visible world … but instead was located quite visibly in the skies

above. Beyond that, Aristotle had no particular opinion about the

"heavenly realm" of the gods or whatever.

|

Go on to the next section: Alexander and Hellenism

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | |

The ancient Greek political-intellectual

The ancient Greek political-intellectual Early philosophical development:

Early philosophical development: Athens' political-social-moral decline

Athens' political-social-moral decline

The Big Three: Socrates, Plato and

The Big Three: Socrates, Plato and