|

|

|

|

|

|

Chinese history

Chinese cultural history. The origins of Chinese civilization are clouded with myth and are subject to much historical controversy. The first serious attempt to put the origins of Chinese society and civilization to historical record only occurred sometime around 1000 A.D. – and even that was done mostly on the basis of ancient traditions and a small amount of archeological material. In fact it was not until the beginning of the 20th century that anything close to the historical standards we rely on in the West began to be brought into the study of Chinese history. Chinese dynastic history. This is not to say that the Chinese were devoid of a sense of history. Actually the case is quite the opposite. The Chinese have long been one of the most - if not the most - historical minded of peoples. Chinese scholars kept a very careful account of at least one element of their 'national' history: the record of the various ruling kings, emperors and dynasties that commanded the country over thousands of years. The purpose of such history was not simply to render some kind of sketch of China and its people during particular political periods ... as is how 'good' history is viewed today. Rather the history that was carefully recorded of the comings and goings and the various doings of China's imperial rulers served an important political function: to demonstrate how the thread of a vital line of authority served to hold together the Chinese community on an ongoing basis, a continuing flow of 'civilized' politics that distinguished the Chinese race from the "barbarians" that surrounded the Chinese and that drifted in and out of their national story (usually as major nuisances!). However ... very unfortunately (as certainly the Chinese themselves understood such matters) this dynastic thread was not always continuous. It was all too frequently broken by period of chaos and disaster when that authority disintegrated ... because of natural disasters which dramatically upset the orderly world of the Chinaman (such as the huge flooding of the Yellow River, or the visit by harvest-destroying locusts, or nomadic hordes who breached the protective Walls supposedly protecting the community, etc) ... or just the inability of weak emperors to hold ambitious clan leaders under check. At such times China would be plunged into such civil chaos that hundreds of thousands of lives would be lost. And China might be visited by a long period of political and economic confusion until a new ruler, and a new dynasty established by such a new imperial figure, could bring China back under order. The moral "centrality" of Chinese society

(China as the central or "Middle Kingdom": the Zongguo This rather ritualized sense of an ongoing line of highly exaulted imperial political-religious authority served to convey the idea of the Chinese community being historically the universally central society or "Middle Kingdom" - or Zongguo - around which all other societies circled as supposedly dependent satellites. ["China" was a term in reference to their land that was unfamiliar to the Chinese until introduced by Westerners in the 1800s.] The Chinese, for the longest time unaware that other civilizations occurred beyond the western slopes of the Pamir Mountains or the southern slopes of the Himalayas, supposed that all human life was organized on a perfectly logical hierarchical basis - from lesser beings (the surrounding, mostly nomadic, "barbarian" peoples) to the Chinese commoners, to the important Chinese ruling clans and their leaders, to the Chinese Emperor and his particular ruling dynasty, and ultimately to the realm of Heaven (Tian) under which the Emperor, the rulilng dynasties and clans, the Chinese people, and the barbaric dependencies drew their power (in reverse order). It was all very logical, all very well organized in the Chinaman's mind as the proper moral arrangement of all human life on this planet (such as they knew human life to exist). And it would serve as a powerful political force which held everyone, including emperors, to some kind of moral account. The Tianming "Mandate of Heaven"

Any breakdown in this order was viewed as a negative force drawn from the top downward in society. The most important of such forces was the hand that Heaven played in the life of Chinese society. Heaven ultimately decided who was to rule and who was not. Heaven sent its support to the ruling elements of the Chinese social-political hierarchy ... offering China blissful peace and prosperity. But a displeased Heaven could as easily withdraw that support ... which would cause China to fall into chaos. Likely explanations for Heaven's negative actions was because of the failure of Emperors to offer proper rutualized sacrifices to Heaven ... or (extremely important) because they failed to demonstrate a proper sense of moral responsibility toward the people. And those responsibilities included protection from barbarian raids, flood control of the mighty Yellow or Yangzi or Wei (or other) rivers that fed the fields of China's vast farming world ... and most frequently, keeping peace among contenting Chinese clans and their leaders (often despised by Chinese commoners as mere warlords). Failure of an emperor to hold the peace and security of China was an indication to the Chinese that the emperor had lost the Mandate of Heaven. This was the signal for the various clans to try to secure the imperial title by a show of superiority in battle with the other clans ... security military victories that offered proof that the Mandate of Heaven had moved to favor this new ruling dynasty under its new Tianzi ("Son of Heaven") ... China's new emperor. Sadly this process of reestablishing the imperial thread of continuity could often take generations ... leaving China in a sad state politically, economically and socially, with the population registering this chaos with a huge dip in their total numbers. But eventually that thread of imperial continuity would be reestablished, China would live on with its sense of historical continuity restored and all would be well under Heaven. And the Chinese historians would continue to write their historical accounts of the dynasties ruling China, in particular the one they lived under as they wrote ... being sure to give glorious account of its doings ... in almost religious demonstration of the whole social order being properly fixed under Heaven.1 This is what the Chinese wanted and expected ... not democracy, but the high moral (and thus politically effective) rule of supreme Chinese political authority. This is what they well understood brought happiness to the land and people. 1Bamboo Annals - written around 300 BC (portions lost or reworked much later) which was basically a dynastic history beginning from the Yellow Emperor (ca. 2600s BC); ... and Records of the Grand Historian - written around 100 BC by Sima Qian, also basically a dynastic history and also beginning from the Yellow Emperor down to Sima Qian's own era. |

|

|

Origins

The Xia Dynasty of the Yellow River Basin. As best as we can piece together the story of China, Chinese civilization began along the northern plains region (or Central Plains because to the Chinese this area was the central region in China's development) bordering the Yellow River (or Huang He) ... named "Yellow" because of the heavy silt mixed in with the waters. This area developed a rich bronze age culture shared by a number of towns located there. This Central Plains or Yellow River Basin area was also united under the rule of a 'Xia Dynasty,' the exact date and identity of which is much debated – but probably somewhere around 2000 to 1600 BC. Coexistence with other societies inhabiting "China" at that time. But we must be careful in using the words "united" and "dynasty." These convey the idea of early China as a tightly organized society reaching across the vast expanse of what is today modern China - the political whole held together by a single family whose rule was passed on from father to son across many generations. Actually there is archeological evidence that there were a number of different communities inhabiting China simulatenously, particularly to the south and west of the Yellow River area ... not by any means under Xia rule. These other societies (such as those south around the Yanzi River region) may have shared many things in common materially or culturally with the Xia of the Yellow River region, but spoke different languages (as they still do today) and even may have been of very different ethnic character, especially those at some distance from the Yellow River Basin. But ultimately the only early or founding communities of interest to the Chinese official historians were those whose history seems in some ways connected to the rise of the Xia, and their successor states under the early Shang, Zhou and Han dynasties centrally based in the Yellow River region. Thus whereas many different societies lived simultaneously under their own political leadership in China, official Chinese history traditionally acknowledges only one ruling dynasty at a time (except during warlord periods when Chinese history hesitantly admits to China being subdivided into a number of separte, rather independent states). This simplifies Chinese history. But it also conveys a serious inaccuracy. Xia culture ... according to tradition.

Tradition

states that the Xia descended from the "Three Sovereigns and Five

Emperors" ... though exactly who these were is a matter of conflicting

historical claims. But in general the Three Sovereigns were the

man-gods who gave the Chinese their various traits and skills ... and

the Five Emperors were rulers whose moral teachings and examples helped

define the earliest ideals of Chinese society (basically family

centered). Tradition

states that the Xia descended from the "Three Sovereigns and Five

Emperors" ... though exactly who these were is a matter of conflicting

historical claims. But in general the Three Sovereigns were the

man-gods who gave the Chinese their various traits and skills ... and

the Five Emperors were rulers whose moral teachings and examples helped

define the earliest ideals of Chinese society (basically family

centered). Among these the "Yellow Emperor" or Huangdi (reputed to have ruled during the 2600s BC) who figures as the most prominent among these founding rulers ... possibly referring to an early deity who was eventually converted by Chinese history into the first "emperor." He represented all the moral qualities that the Chinese claimed that any emperor must exemplify. He was also claimed to be the inventor of a vast number of Chinese cultural items, including early writing, math, music, laws, tools, transport items, sports, etc., etc. Furthermore, supposedly all "Han" Chinese are descendents of his (this idea was suppressed during the Maoist period of the mid-20th century, but recently revived). |

|

|

The Yellow River civilization and the Shang Dynasty

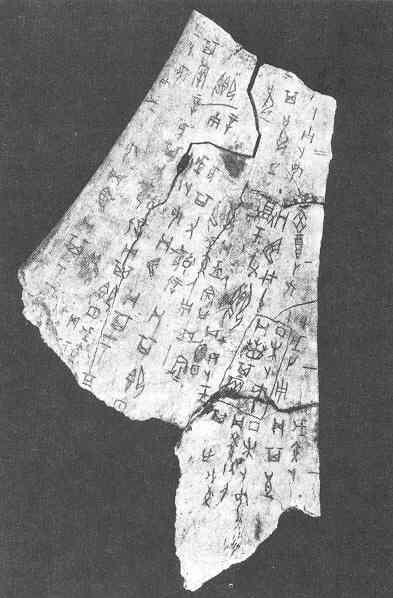

It is not until the 1300s or so BC, when the Yellow River region was under the Shang Dynasty (ca. mid 1700s to the mid 1000s BC), that we begin to get a better (though still limited) picture of ancient Chinese society and culture. We can be fairly certain of this dynasty’s rule from Erlingang and Zengzhou in its earlier phase and from Yin (Anyang) in its later, "golden" period. But how far Shang rule extended beyond this region we do not know. There were likely other dynasties ruling simultaneously in other areas of China (such as the ones at Hemudu southeast of this area and Chengdu to the southwest... which left a rich record of wealth and power of their own right). But it is on the Shang Dyanasty that official Chinese history focuses. Thirty-one Shang kings are known by name according to an ancient kings list and it is known that they located their capitals in different cities at different times during the Shang era. The oracle bones. Two very important archeological finds form the basis of what we know of China during the Shang era. One of these are the large deposits of oracle bones or shells found at Yinxu, near the city of Anyang. turtle undershells or ox shoulder blades that were heated and cracked ... the cracking offering an answer from Heaven concerning a request for divine insight or information concerning a particular problem. The answers were than usually recorded (in characters surprisingly closely related to modern Chinese writing) on the bones ... offering us today insight into aspects of Shang cultural life ... life at least as it was lived by the Shang kings and their families ... as it was one of the king's duties to perform these rites of interpreting the oracle bones. Consulting the ancestors. Interestingly, whom they consulted was not the deities of heaven themselves ... but rather departed ancestors - who were expected to have access to the doings of Heaven and thus from their lofty position be able to continue to guide the living community that the living Shang king was responsible for. This gives us a clear insight into the importance of ancestor worship. Ancestors were to be respected (even feared) and appeased with offerings ... and with obedience to the information relayed through the oracles. This concerned everything from the day's coming weather, to births, to wars, to agricultural decisisons. to marriages, etc. The heavy bronzeware. The second important archeological find at the Shang capital (Yinxu) was the massive amount of fancy bronzeware uncovered at one of the burial sites that had excaped the notice of grave robbers over the centuries. The social implications of this find were clear: the labor and expense involved in the mining of the copper, tin and lead needed to make the tinware pointed to a very wealthy and probably very small class of very privileged owners of such bronzeware ... and the cheapness of the labor (and consequent poverty of the laboring class) that made this bronzeware possible. Archeological evidence points to the relative splendor of the homes of the ruling elite ... and the crushing poverty (some homes seemed to have been no more than roofed pits dug into the ground to house a working-class family). |

Chinese oracle bone pit at

the late Shang Dynasty capital of Yinxu (near modern Anyang)

Chinese oracle bone from

the Shang Dynasty

Columbia University (East

Asian Library)

Bronzeware excavated at the

tomb of Lady Fu Hao, Yinxu

Houmuwu Ding made in the

late Shang Dynasty at Anyang

This wine vessel is the

heaviest piece of bronze work found in China so far.

Height 133 cm, width 112

cm, depth 79.2 cm, weight 875 kg.

The National Museum of

China.

Chinese bronze wine vessel

from the Shang Dynasty

The Metropolitan Museum

of Art, Rogers Fund 1943

Bronze owl-shaped vessel

(zun), Late Shang Period (c. 1200 B.C.)

The Institute of Archaeology,

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing

Bronze two-sided mask, Late

Shang Period (c. 1200-1050 B.C.)

Jiangxi Provincial

Museum, Nanchang

Bronze standing figure, Late

Shang Period (c. 1300-1100 B.C.)

Sanxingdui

Museum, Guanghan

|

|

The declining days of the Shang Dynasty

As the centuries advanced the effective hold of the Shang kings was reduced to an ever smaller area, with other principalities operating rather independently. However there still remained a sense of legitimacy in having the Shang kings serve ritually as the primary link between the people and Heaven ... with the Shang kings busied reading and recording on the oracle bones Heaven's opinion on every conceiveable matter affecting the region. Thus it was that rulership in China was early identified with a ruling dynasty's close relationship with the powers of Heaven ... and with the management of a literate bureaucracy which carefully recorded (in a style amazingly similar to the Chinese writing in use today) these communications. The Western Zhou Dynasty

Eventually a new dynasty came to the fore in China, the Zhou Dynasty. This dynasty originated along the Yellow River as a Western Shang territory, whose regional governor, Duke Wu led a successful revolt against the Shang king, Di Xin in 1045 BC. He thus became king and founder of a new Chinese dynasty... though he enjoyed this privilege only briefly, dying two years later. The Duke of Zhou and the Tianming (Mandate of Heaven). To give legitimacy to this overthrow of traditional Shang authority, Wu's younger brother, the Duke of Zhou (who as uncle of Wu's young son became the young king's protector or regent), claimed that his family had been successful in this challenge to traditional authority because it possessed the Tianming. The Mandate of Heaven would immediately need to be verified ... as a number of jealous Zhou brothers joined with the Shang in rebellion. The Duke however organized a major military offensive which not only swept away the challengers, but brought Zhou rule effectively all the way down the Yellow River to the Sea. Distinctly, the young Zhou King Cheng and his protector, the Duke of Zhou, had demonstrated clearly how important it was that they possessed the Mandate of Heaven. The feudal foundations of Zhou rule. To govern this vast territory from their capital at Fenghao (today's Xi'an), family members and military commanders were assigned sections of the new kingdom to administer ... forming the basis of an aristocratic rulership that would be the forerunners of a number of famous families and dynasties that would eventually come to rule China The Duke of Zhou as the perfect example of the moral ruler. After seven years of serving as the regent to the young King Cheng, the Duke of Zhou (who truly established Zhou rule in Northern China) retired from his duties - an act of such generosity and spirit of public service that he became heroized as the model of the perfect ruler ... creating a moral standard politically that all subsequent Chinese rulers would be measured against. This was the type of ruler that Heaven favored and mandated. Thus it was that political morality and political success were closely linked in the thinking of the Chinese. The expansion of Zhou rule

The Zhou domain gradually - over the centuries - spread its symbolic rule southward to the Yangtze River – accompanied by a southward expansion of the Chinese population (the beginning of a Chinese migratory pattern that would force the original inhabitants of China, such as the Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians, down into the Indo-Chinese peninsula). Chinese culture under the Western Zhou Dynasty

It would be during the Zhou Dynasty that the cultural features that we identify as typically Chinese took shape. It was a time of great intellectual activity as well as material achievement. Chinese pictographic script or writing took its familiar shape during this time, Chinese artistic styles developed, and classical principles and laws of Chinese political administration established. The long-standing ancestor worship of the Chinese was blended with Chinese political theory to produce a strong sense of governmental legitimacy linking the Chinese king or emperor emotionally to the Chinese population: the emperor was something of a chief father-figure given the right to rule by the judgment of Heaven itself, demonstrated in his visible military, economic and administrative success that he was the Tianzi (Son of Heaven.) But by the same token, failure of a ruler to handle natural disasters or provide strong defense of the land against foreign enemies or prevent corruption from infecting Chinese political administration, worked equally powerfully in the eyes of the Chinese against his right to rule – setting up the right of some political challenger to demonstrate that he now possessed the "Mandate of Heaven." Success in battle between the challenger and the challenged ultimately resolved the matter in the opinion of the Chinese. Literary and artistic development

Although the Zhou kings continued the practice of divining oracles with cracked bones, they added to this practice - and eventually displaced it - with the reading of oracles through the casting of six special sticks ... and divining the resulting configuration (a form of hexigram). References to this form of divination are found widely in the literary work composed sometime during the 800s BC: the Yijing (I-Ching) or "Book of Changes." Another literary work composed during this same period, the Shijing or "Book of Songs" testifies to the early poetic and musical style that matured with further Chinese cultural development. Indeed, during these early years of the Zhou Dynasty, Chinese artistic culture began to take on very clear, very distinctive and very enduring national traits. The dynastic cycle

As was so typical of things politically, the Zhou rule under the founding generation of the Duke of Zhou and his nephew Cheng (1035-1003 BC) ... and Cheng's son Kang (1003-978 BC) was a time of great unity and prosperity. Then troubles set in with following generations. Political subordinates became more independent, even rebellious, and the political grip of the Zhou monarchy loosened over the country. In typical feudal fashion, the Zhou domain remained held together loosely in part by the family politics of the ruling Zhou, supported by a growing bureaucracy of professional administrators and by the Zhou army. Here too, the ebb and flow of Zhou power was directly dependent upon the personal strengths of various Zhou kings (or emperors) ... reflecting the Tianming. But more importantly, the religious or ritualistic role of the Zhou kings remained strong despite the loose political ties ... and key symbolically to the cultural unity which still characterized the period. In the eyes of the Chinese people, the Zhou kings served spiritually as vital intercessors between the Chinese people and the forces of Heaven (principally the royal ancestors in Heaven in a position there to aid ... or trouble ... the earthly community). This ritualistic role (offering the sacrifices and receiving the oracles from Heaven) came to be viewed as the most important of all kingly responsibilities - one understood as vital to the life of earthly community ... even more important than direct political or military rule (which was devolving to the ducal level of the various families ruling China's various provinces). |

Ancestor "worship"

Burning incense at a grave

in the Qichun village, Hubei province, China

Wikipedia - "Ancestor

worship"

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges