SOCIAL CONTRACT

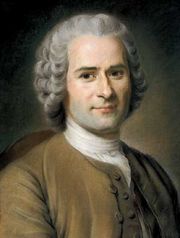

by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

1762

Translated by G. D. H. Cole

Book One

FORWARD This little treatise is part of a longer work which I began years ago without realising my limitations, and long since abandoned. Of the various fragments that might have been extracted from what I wrote, this is the most considerable, and, I think, the least unworthy of being offered to the public. The rest no longer exists.

AVERTISSEMENT Ce petit traité est extrait d'un ouvrage plus étendu, entrepris autrefois sans avoir consulté mes forces, et abandonné depuis longtemps. Des divers morceaux qu'on pouvait tirer de ce qui était fait celui-ci est le plus considérable, et m'a paru le moins indigne d'être offert au public. Le reste n'est déjà plus.

BOOK I I MEAN to inquire if, in the civil order, there can be any sure and legitimate rule of administration, men being taken as they are and laws as they might be. In this inquiry I shall endeavour always to unite what right sanctions with what is prescribed by interest, in order that justice and utility may in no case be divided.

I enter upon my task without proving the importance of the subject. I shall be asked if I am a prince or a legislator, to write on politics. I answer that I am neither, and that is why I do so. If I were a prince or a legislator, I should not waste time in saying what wants doing; I should do it, or hold my peace.

As I was born a citizen of a free State, and a member of the Sovereign, I feel that, however feeble the influence my voice can have on public affairs, the right of voting on them makes it my duty to study them: and I am happy, when I reflect upon governments, to find my inquiries always furnish me with new reasons for loving that of my own country.

LIVRE PREMIER Je veux chercher si dans l'ordre civil il peut y avoir quelque règle d'administration légitime et sûre, en prenant les hommes tels qu'ils sont, et les lois telles qu'elles peuvent être. Je tâcherai d'allier toujours dans cette recherche ce que le droit permet avec ce que l'intérêt prescrit, afin que la justice et l'utilité ne se trouvent point divisées.

J'entre en matière sans prouver l'importance de mon sujet. On me demandera si je suis prince ou législateur pour écrire sur la Politique? Je réponds que non, et que c'est pour cela que j'écris sur la Politique. Si j'étais prince ou législateur, je ne perdrais pas mon temps à dire ce qu'il faut faire; je le ferais, ou je me tairais.

Né citoyen d'un Etat libre, et membre du souverain, quelque faible influence que puisse avoir ma voix dans les affaires publiques, le droit d'y voter suffit pour m'imposer le devoir de m'en instruire. Heureux, toutes les fois que je médite sur les gouvernements, de trouver toujours dans mes recherches de nouvelles raisons d'aimer celui de mon pays!

FIRST CHAPTER SUBJECT OF THE FIRST BOOK

MAN is born free; and everywhere he is in chains. One thinks himself the master of others, and still remains a greater slave than they. How did this change come about? I do not know. What can make it legitimate? That question I think I can answer.

If I took into account only force, and the effects derived from it, I should say: "As long as a people is compelled to obey, and obeys, it does well; as soon as it can shake off the yoke, and shakes it off, it does still better; for, regaining its liberty by the same right as took it away, either it is justified in resuming it, or there was no justification for those who took it away." But the social order is a sacred right which is the basis of all other rights. Nevertheless, this right does not come from nature, and must therefore be founded on conventions. Before coming to that, I have to prove what I have just asserted.

CHAPITRE PREMIER SUJET DE CE PREMIER LIVRE

L'homme est né libre, et partout il est dans les fers. Tel se croit le maître des autres, qui ne laisse pas d'être plus esclave qu'eux. Comment ce changement s'est-il fait? Je l'ignore. Qu'est-ce qui peut le rendre légitime? Je crois pouvoir résoudre cette question.

Si je ne considérais que la force, et l'effet qui en dérive, je dirais: Tant qu'un peuple est contraint d'obéir et qu'il obéit, il fait bien; sitôt qu'il peut secouer le joug et qu'il le secoue, il fait encore mieux; car, recouvrant sa liberté par le même droit qui la lui a ravie, ou il est fondé à la reprendre, ou l'on ne l'était point à la lui ôter. Mais l'ordre social est un droit sacré, qui sert de base à tous les autres. Cependant ce droit ne vient point de la nature; il est donc fondé sur des conventions. Il s'agit de savoir quelles sont ces conventions. Avant d'en venir là je dois établir ce que je viens d'avancer.

CHAPTER II THE FIRST SOCIETIES

THE most ancient of all societies, and the only one that is natural, is the family: and even so the children remain attached to the father only so long as they need him for their preservation. As soon as this need ceases, the natural bond is dissolved. The children, released from the obedience they owed to the father, and the father, released from the care he owed his children, return equally to independence. If they remain united, they continue so no longer naturally, but voluntarily; and the family itself is then maintained only by convention.

This common liberty results from the nature of man. His first law is to provide for his own preservation, his first cares are those which he owes to himself; and, as soon as he reaches years of discretion, he is the sole judge of the proper means of preserving himself, and consequently becomes his own master.

The family then may be called the first model of political societies: the ruler corresponds to the father, and the people to the children; and all, being born free and equal, alienate their liberty only for their own advantage. The whole difference is that, in the family, the love of the father for his children repays him for the care he takes of them, while, in the State, the pleasure of commanding takes the place of the love which the chief cannot have for the peoples under him.

Grotius denies that all human power is established in favour of the governed, and quotes slavery as an example. His usual method of reasoning is constantly to establish right by fact.1 It would be possible to employ a more logical method, but none could be more favourable to tyrants.

It is then, according to Grotius, doubtful whether the human race belongs to a hundred men, or that hundred men to the human race: and, throughout his book, he seems to incline to the former alternative, which is also the view of Hobbes. On this showing, the human species is divided into so many herds of cattle, each with its ruler, who keeps guard over them for the purpose of devouring them.

As a shepherd is of a nature superior to that of his flock, the shepherds of men, i.e., their rulers, are of a nature superior to that of the peoples under them. Thus, Philo tells us, the Emperor Caligula reasoned, concluding equally well either that kings were gods, or that men were beasts.

The reasoning of Caligula agrees with that of Hobbes and Grotius. Aristotle, before any of them, had said that men are by no means equal naturally, but that some are born for slavery, and others for dominion.

Aristotle was right; but he took the effect for the cause. Nothing can be more certain than that every man born in slavery is born for slavery. Slaves lose everything in their chains, even the desire of escaping from them: they love their servitude, as the comrades of Ulysses loved their brutish condition.2 If then there are slaves by nature, it is because there have been slaves against nature. Force made the first slaves, and their cowardice perpetuated the condition.

I have said nothing of King Adam, or Emperor Noah, father of the three great monarchs who shared out the universe, like the children of Saturn, whom some scholars have recognised in them. I trust to getting due thanks for my moderation; for, being a direct descendant of one of these princes, perhaps of the eldest branch, how do I know that a verification of titles might not leave me the legitimate king of the human race? In any case, there can be no doubt that Adam was sovereign of the world, as Robinson Crusoe was of his island, as long as he was its only inhabitant; and this empire had the advantage that the monarch, safe on his throne, had no rebellions, wars, or conspirators to fear.

CHAPITRE II DES PREMIERES SOCIETES

La plus ancienne de toutes les sociétés et la seule naturelle est celle de la famille. Encore les enfants ne restent-ils liés au père qu'aussi longtemps qu'ils ont besoin de lui pour se conserver. Sitôt que ce besoin cesse, le lien naturel se dissout. Les enfants, exempts de l'obéissance qu'ils devaient au père, le père exempt des soins qu'il devait aux enfants, rentrent tous également dans l'indépendance. S'ils continuent de rester unis ce n'est plus naturellement, c'est volontaire- ment, et la famille elle-même ne se maintient que par convention.

Cette liberté commune est une conséquence de la nature de l'homme. Sa première loi est de veiller à sa propre conservation, ses premiers soins sont ceux qu'il se doit à lui-même, et, sitôt qu'il est en âge de raison, lui seul étant juge des moyens propres à se conserver devient par là son propre maître.

La famille est donc si l'on veut le premier modèle des sociétés politiques; le chef est l'image du père, le peuple est l'image des enfants, et tous étant nés égaux et libres n'aliènent leur liberté que pour leur utilité. Toute la différence est que dans la famille l'amour du père pour ses enfants le paye des soins qu'il leur rend, et que dans l'Etat le plaisir de commander supplée à cet amour que le chef n'a pas pour ses peuples.

Grotius nie que tout pouvoir humain soit établi en faveur de ceux qui sont gouvernés: Il cite l'esclavage en exemple. Sa plus constante manière de raisonner est d'établir toujours le droit par le fait.1 On pourrait employer une méthode plus conséquente, mais non pas plus favorable aux tyrans.

Il est donc douteux, selon Grotius, si le genre humain appartient à une centaine d'hommes, ou si cette centaine d'hommes appartient au genre humain, et il paraît dans tout son livre pencher pour le premier avis: c'est aussi le sentiment de Hobbes. Ainsi voilà l'espèce humaine divisée en troupeaux de bétail, dont chacun a son chef, qui le garde pour le dévorer.

Comme un pâtre est d'une nature supérieure à celle de son troupeau, les pasteurs d'hommes, qui sont leurs chefs, sont aussi d'une nature supérieure à celle de leurs peuples. Ainsi raisonnait, au rapport de Philon, l'empereur Caligula; concluant assez bien de cette analogie que les rois étaient des dieux, ou que les peuples étaient des bêtes.

Le raisonnement de ce Caligula revient à celui d'Hobbes et de Grotius. Aristote avant eux tous avait dit aussi que les hommes ne sont point naturellement égaux, mais que les uns naissent pour l'esclavage et les autres pour la domination.

Aristote avait raison, mais il prenait l'effet pour la cause. Tout homme né dans l'esclavage naît pour l'esclavage, rien n'est plus certain. Les esclaves perdent tout dans leurs fers, jusqu'au désir d'en sortir; ils aiment leur servitude comme les compagnons d'Ulysse aimaient leur abrutissement.2 S'il y a donc des esclaves par nature, c'est parce qu'il y a eu des esclaves contre nature. La force a fait les premiers esclaves, leur lâcheté les a perpétués.

Je n'ai rien dit du roi Adam, ni de l'empereur Noé père de trois grands monarques qui se partagèrent l'univers, comme firent les enfants de Saturne, qu'on a cru reconnaître en eux. J'espère qu'on me saura gré de cette modération; car, descendant directement de l'un de ces princes, et peut-être de la branche aînée, que sais-je si par la vérification des titres je ne me trouverais point le légitime roi du genre humain? Quoi qu'il en soit, on ne peut disconvenir qu'Adam n'ait été souverain du monde comme Robinson de son île, tant qu'il en fut le seul habitant; et ce qu'il y avait de commode dans cet empire était que le monarque assuré sur son trône n'avait à craindre ni rébellions ni guerres ni conspirateurs.

CHAPTER III THE RIGHT OF THE STRONGEST

THE strongest is never strong enough to be always the master, unless he transforms strength into right, and obedience into duty. Hence the right of the strongest, which, though to all seeming meant ironically, is really laid down as a fundamental principle. But are we never to have an explanation of this phrase? Force is a physical power, and I fail to see what moral effect it can have. To yield to force is an act of necessity, not of will — at the most, an act of prudence. In what sense can it be a duty?

Suppose for a moment that this so-called "right" exists. I maintain that the sole result is a mass of inexplicable nonsense. For, if force creates right, the effect changes with the cause: every force that is greater than the first succeeds to its right. As soon as it is possible to disobey with impunity, disobedience is legitimate; and, the strongest being always in the right, the only thing that matters is to act so as to become the strongest. But what kind of right is that which perishes when force fails? If we must obey perforce, there is no need to obey because we ought; and if we are not forced to obey, we are under no obligation to do so. Clearly, the word "right" adds nothing to force: in this connection, it means absolutely nothing.

Obey the powers that be. If this means yield to force, it is a good precept, but superfluous: I can answer for its never being violated. All power comes from God, I admit; but so does all sickness: does that mean that we are forbidden to call in the doctor? A brigand surprises me at the edge of a wood: must I not merely surrender my purse on compulsion; but, even if I could withhold it, am I in conscience bound to give it up? For certainly the pistol he holds is also a power.

Let us then admit that force does not create right, and that we are obliged to obey only legitimate powers. In that case, my original question recurs.

CHAPITRE III DU DROIT DU PLUS FORT

Le plus fort n'est jamais assez fort pour être toujours le maître, s'il ne transforme sa force en droit et l'obéissance en devoir. De là le droit du plus fort; droit pris ironiquement en apparence, et réellement établi en principe: Mais ne nous expliquera-t-on jamais ce mot? La force est une puissance physique; je ne vois point quelle moralité peut résulter de ses effets. Céder à la force est un acte de nécessité, non de volonté; c'est tout au plus un acte de prudence. En quel sens pourra-ce être un devoir?

Supposons un moment ce prétendu droit. Je dis qu'il n'en résulte qu'un galimatias inexplicable. Car sitôt que c'est la force qui fait le droit, l'effet change avec la cause; toute force qui surmonte la première succède à son droit. Sitôt qu'on peut désobéir impunément on le peut légitimement, et puisque le plus fort a toujours raison, il ne s'agit que de faire en sorte qu'on soit le plus fort. Or qu'est-ce qu'un droit qui périt quand la force cesse? S'il faut obéir par force on n'a pas besoin d'obéir par devoir, et si l'on n'est plus forcé d'obéir on n'y est plus obligé. On voit donc que ce mot de droit n'ajoute rien à la force; il ne signifie ici rien du tout.

Obéissez aux puissances. Si cela veut dire, cédez à la force, le précepte est bon, mais superflu, je réponds qu'il ne sera jamais violé. Toute puissance vient de Dieu, je l'avoue; mais toute maladie en vient aussi. Est-ce à dire qu'il soit défendu d'appeler le médecin? Qu'un brigand me surprenne au coin d'un bois: non seulement il faut par force donner la bourse, mais quand je pourrais la soustraire suis-je en conscience obligé de la donner? car enfin le pistolet qu'il tient est aussi une puissance.

Convenons donc que force ne fait pas droit, et qu'on n'est obligé d'obéir qu'aux puissances légitimes. Ainsi ma question primitive revient toujours.

CHAPTER IV SLAVERY

SINCE no man has a natural authority over his fellow, and force creates no right, we must conclude that conventions form the basis of all legitimate authority among men.

If an individual, says Grotius, can alienate his liberty and make himself the slave of a master, why could not a whole people do the same and make itself subject to a king? There are in this passage plenty of ambiguous words which would need explaining; but let us confine ourselves to the word alienate. To alienate is to give or to sell. Now, a man who becomes the slave of another does not give himself; he sells himself, at the least for his subsistence: but for what does a people sell itself? A king is so far from furnishing his subjects with their subsistence that he gets his own only from them; and, according to Rabelais, kings do not live on nothing. Do subjects then give their persons on condition that the king takes their goods also? I fail to see what they have left to preserve.

It will be said that the despot assures his subjects civil tranquillity. Granted; but what do they gain, if the wars his ambition brings down upon them, his insatiable avidity, and the vexations conduct of his ministers press harder on them than their own dissensions would have done? What do they gain, if the very tranquillity they enjoy is one of their miseries? Tranquillity is found also in dungeons; but is that enough to make them desirable places to live in? The Greeks imprisoned in the cave of the Cyclops lived there very tranquilly, while they were awaiting their turn to be devoured.

To say that a man gives himself gratuitously, is to say what is absurd and inconceivable; such an act is null and illegitimate, from the mere fact that he who does it is out of his mind. To say the same of a whole people is to suppose a people of madmen; and madness creates no right.

Even if each man could alienate himself, he could not alienate his children: they are born men and free; their liberty belongs to them, and no one but they has the right to dispose of it. Before they come to years of discretion, the father can, in their name, lay down conditions for their preservation and well-being, but he cannot give them irrevocably and without conditions: such a gift is contrary to the ends of nature, and exceeds the rights of paternity. It would therefore be necessary, in order to legitimise an arbitrary government, that in every generation the people should be in a position to accept or reject it; but, were this so, the government would be no longer arbitrary.

To renounce liberty is to renounce being a man, to surrender the rights of humanity and even its duties. For him who renounces everything no indemnity is possible. Such a renunciation is incompatible with man's nature; to remove all liberty from his will is to remove all morality from his acts. Finally, it is an empty and contradictory convention that sets up, on the one side, absolute authority, and, on the other, unlimited obedience. Is it not clear that we can be under no obligation to a person from whom we have the right to exact everything? Does not this condition alone, in the absence of equivalence or exchange, in itself involve the nullity of the act? For what right can my slave have against me, when all that he has belongs to me, and, his right being mine, this right of mine against myself is a phrase devoid of meaning?

Grotius and the rest find in war another origin for the so-called right of slavery. The victor having, as they hold, the right of killing the vanquished, the latter can buy back his life at the price of his liberty; and this convention is the more legitimate because it is to the advantage of both parties.

But it is clear that this supposed right to kill the conquered is by no means deducible from the state of war. Men, from the mere fact that, while they are living in their primitive independence, they have no mutual relations stable enough to constitute either the state of peace or the state of war, cannot be naturally enemies. War is constituted by a relation between things, and not between persons; and, as the state of war cannot arise out of simple personal relations, but only out of real relations, private war, or war of man with man, can exist neither in the state of nature, where there is no constant property, nor in the social state, where everything is under the authority of the laws.

Individual combats, duels and encounters, are acts which cannot constitute a state; while the private wars, authorised by the Establishments of Louis IX, King of France, and suspended by the Peace of God, are abuses of feudalism, in itself an absurd system if ever there was one, and contrary to the principles of natural right and to all good polity.

War then is a relation, not between man and man, but between State and State, and individuals are enemies only accidentally, not as men, nor even as citizens,3 but as soldiers; not as members of their country, but as its defenders. Finally, each State can have for enemies only other States, and not men; for between things disparate in nature there can be no real relation.

Furthermore, this principle is in conformity with the established rules of all times and the constant practice of all civilised peoples. Declarations of war are intimations less to powers than to their subjects. The foreigner, whether king, individual, or people, who robs, kills or detains the subjects, without declaring war on the prince, is not an enemy, but a brigand. Even in real war, a just prince, while laying hands, in the enemy's country, on all that belongs to the public, respects the lives and goods of individuals: he respects rights on which his own are founded. The object of the war being the destruction of the hostile State, the other side has a right to kill its defenders, while they are bearing arms; but as soon as they lay them down and surrender, they cease to be enemies or instruments of the enemy, and become once more merely men, whose life no one has any right to take. Sometimes it is possible to kill the State without killing a single one of its members; and war gives no right which is not necessary to the gaining of its object. These principles are not those of Grotius: they are not based on the authority of poets, but derived from the nature of reality and based on reason.

The right of conquest has no foundation other than the right of the strongest. If war does not give the conqueror the right to massacre the conquered peoples, the right to enslave them cannot be based upon a right which does not exist. No one has a right to kill an enemy except when he cannot make him a slave, and the right to enslave him cannot therefore be derived from the right to kill him. It is accordingly an unfair exchange to make him buy at the price of his liberty his life, over which the victor holds no right. Is it not clear that there is a vicious circle in founding the right of life and death on the right of slavery, and the right of slavery on the right of life and death?

Even if we assume this terrible right to kill everybody, I maintain that a slave made in war, or a conquered people, is under no obligation to a master, except to obey him as far as he is compelled to do so. By taking an equivalent for his life, the victor has not done him a favour; instead of killing him without profit, he has killed him usefully. So far then is he from acquiring over him any authority in addition to that of force, that the state of war continues to subsist between them: their mutual relation is the effect of it, and the usage of the right of war does not imply a treaty of peace. A convention has indeed been made; but this convention, so far from destroying the state of war, presupposes its continuance.

So, from whatever aspect we regard the question, the right of slavery is null and void, not only as being illegitimate, but also because it is absurd and meaningless. The words slave and right contradict each other, and are mutually exclusive. It will always be equally foolish for a man to say to a man or to a people: "I make with you a convention wholly at your expense and wholly to my advantage; I shall keep it as long as I like, and you will keep it as long as I like."

CHAPITRE IV DE L'ESCLAVAGE

Puisque aucun homme n'a une autorité naturelle sur son semblable, et puisque la force ne produit aucun droit, restent donc les conventions pour base de toute autorité légitime parmi les hommes.

Si un particulier, dit Grotius, peut aliéner sa liberté et se rendre esclave d'un maître, pourquoi tout un peuple ne pourrait-il pas aliéner la sienne et se rendre sujet d'un roi? Il y a là bien des mots équivoques qui auraient besoin d'explication, mais tenons-nous-en à celui d'aliéner. Aliéner c'est donner ou vendre. Or un homme qui se fait esclave d'un autre ne se donne pas, il se vend, tout au moins pour sa subsistance: mais un peuple pour quoi se vend-il? Bien loin qu'un roi fournisse à ses sujets leur subsistance il ne tire la sienne que d'eux, et selon Rabelais un roi ne vit pas de peu. Les sujets donnent donc leur personne à condition qu'on prendra aussi leur bien? Je ne vois pas ce qu'il leur reste à conserver.

On dira que le despote assure à ses sujets la tranquillité civile. Soit; mais qu'y gagnent-ils, si les guerres que son ambition leur attire, si son insatiable avidité, si les vexations de son ministère les désolent plus que ne feraient leurs dissensions? Qu'y gagnent-ils, si cette tranquillité même est une de leurs misères? On vit tranquille aussi dans les cachots; en est-ce assez pour s'y trouver bien? Les Grecs enfermés dans l'antre du Cyclope y vivaient tranquilles, en attendant que leur tour vînt d'être dévorés.

Dire qu'un homme se donne gratuitement, c'est dire une chose absurde et inconcevable; un tel acte est illégitime et nul, par cela seul que celui qui le fait n'est pas dans son bon sens. Dire la même chose de tout un peuple, c'est supposer un peuple de fous: la folie ne fait pas droit.

Quand chacun pourrait s'aliéner lui-même, il ne peut aliéner ses enfants; ils naissent hommes et libres; leur liberté leur appartient, nul n'a droit d'en disposer qu'eux. Avant qu'ils soient en âge de raison le père peut en leur nom stipuler des conditions pour leur conservation, pour leur bien-être; mais non les donner irrévocablement et sans condition; car un tel don est contraire aux fins de la nature et passe les droits de la paternité. Il faudrait donc pour qu'un gouvernement arbitraire fut légitime qu'à chaque génération le peuple fût le maître de l'admettre ou de le rejeter: mais alors ce gouvernement ne serait plus arbitraire.

Renoncer à sa liberté c'est renoncer à sa qualité d'homme, aux droits de l'humanité, même à ses devoirs. Il n'y a nul dédommagement possible pour quiconque renonce à tout. Une telle renonciation est incompatible avec la nature de l'homme, et c'est ôter toute moralité à ses actions que d'ôter toute liberté à sa volonté. Enfin c'est une convention vaine et contradictoire de stipuler d'une part une autorité absolue et de l'autre une obéissance sans bornes. N'est-il pas clair qu'on n'est engagé à rien envers celui dont on a droit de tout exiger, et cette seule condition, sans équivalent, sans échange n'entraîne-t-elle pas la nullité de l'acte? Car quel droit mon esclave aurait-il contre moi, puisque tout ce qu'il a m'appartient, et que son droit étant le mien, ce droit de moi contre moi-même est un mot qui n'a aucun sens?

Grotius et les autres tirent de la guerre une autre origine du prétendu droit d'esclavage. Le vainqueur ayant, selon eux, le droit de tuer le vaincu, celui-ci peut racheter sa vie aux dépens de sa liberté; convention d'autant plus légitime qu'elle tourne au profit de tous deux.

Mais il est clair que ce prétendu droit de tuer les vaincus ne résulte en aucune manière de l'état de guerre. Par cela seul que les hommes vivant dans leur primitive indépendance n'ont point entre eux de rapport assez constant pour constituer ni l'état de paix ni l'état de guerre, ils ne sont point naturellement ennemis. C'est le rapport des choses et non des hommes qui constitue la guerre, et l'état de guerre ne pouvant naître des simples relations personnelles, mais seulement des relations réelles, la guerre privée ou d'homme à homme ne peut exister, ni dans l'état de nature où il n'y a point de propriété constante, ni dans l'état social où tout est sous l'autorité des lois.

Les combats particuliers, les duels, les rencontres sont des actes qui ne constituent point un état; et à l'égard des guerres privées, autorisées par les établissements de Louis IX roi de France et suspendues par la paix de Dieu, ce sont des abus du gouvernement féodal, système absurde s'il en fut jamais, contraire aux principes du droit naturel, et à toute bonne politie.

La guerre n'est donc point une relation d'homme à homme, mais une relation d'Etat à Etat, dans laquelle les particuliers ne sont ennemis qu'accidentellement, non point comme hommes ni même comme citoyens,3 mais comme soldats; non point comme membres de la patrie, mais comme ses défenseurs. Enfin chaque Etat ne peut avoir pour ennemis que d'autres Etats et non pas des hommes, attendu qu'entre choses de diverses natures on ne peut fixer aucun vrai rapport.

Ce principe est même conforme aux maximes établies de tous les temps et à la pratique constante de tous les peuples policés. Les déclarations de guerre sont moins des avertissements aux puissances qu'à leurs sujets. L'étranger, soit roi, soit particulier, soit peuple, qui vole, tue ou détient les sujets sans déclarer la guerre au prince, n'est pas un ennemi, c'est un brigand. Même en pleine guerre un prince juste s'empare bien en pays ennemi de tout ce qui appartient au public, mais il respecte la personne et les biens des particuliers; il respecte des droits sur lesquels sont fondés les siens. La fin de la guerre étant la destruction de l'Etat ennemi, on a droit d'en tuer les défenseurs tant qu'ils ont les armes à la main; mais sitôt qu'ils les posent et se rendent, cessant d'être ennemis ou instruments de l'ennemi, ils redeviennent simplement hommes et l'on n'a plus de droit sur leur vie. Quelquefois on peut tuer l'Etat sans tuer un seul de ses membres: or la guerre ne donne aucun droit qui ne soit nécessaire à sa fin. Ces principes ne sont pas ceux de Grotius; ils ne sont pas fondés sur des autorités de poètes, mais ils dérivent de la nature des choses, et sont fondés sur la raison.

A l'égard du droit de conquête, il n'a d'autre fondement que la loi du plus fort. Si la guerre ne donne point au vainqueur le droit de massacrer les peuples vaincus ce droit qu'il n'a pas ne peut fonder celui de les asservir. On n'a le droit de tuer l'ennemi que quand on ne peut le faire esclave; le droit de le faire esclave ne vient donc pas du droit de le tuer: c'est donc un échange inique de lui faire acheter au prix de sa liberté sa vie sur laquelle on n'a aucun droit. En établissant le droit de vie et de mort sur le droit d'esclavage, et le droit d'esclavage sur le droit de vie et de mort, n'est-il pas clair qu'on tombe dans le cercle vicieux?

En supposant même ce terrible droit de tout tuer, je dis qu'un esclave fait à la guerre ou un peuple conquis n'est tenu à rien du tout envers son maître, qu'à lui obéir autant qu'il y est forcé. En prenant un équivalent à sa vie le vainqueur ne lui en a point fait grâce: au lieu de le tuer sans fruit il l'a tué utilement. Loin donc qu'il ait acquis sur lui nulle autorité jointe à la force, l'état de guerre subsiste entre eux comme auparavant, leur relation même en est l'effet, et l'usage du droit de la guerre ne suppose aucun traité de paix. Ils ont fait une convention; soit: mais cette convention, loin de détruire l'état de guerre, en suppose la continuité.

Ainsi, de quelque sens qu'on envisage les choses, le droit d'esclave est nul, non seulement parce qu'il est illégitime, mais parce qu'il est absurde et ne signifie rien. Ces mots, esclavage et droit, sont contradictoires; ils s'excluent mutuellement. Soit d'un homme à un homme, soit d'un homme à un peuple, ce discours sera toujours également insensé. Je fais avec toi une convention toute à ta charge et toute à mon profit, que j'observerai tant qu'il me plaira, et que tu observeras tant qu'il me plaira.

CHAPTER V

THAT WE MUST ALWAYS GO BACK TO A FIRST CONVENTIONEVEN if I granted all that I have been refuting, the friends of despotism would be no better off. There will always be a great difference between subduing a multitude and ruling a society. Even if scattered individuals were successively enslaved by one man, however numerous they might be, I still see no more than a master and his slaves, and certainly not a people and its ruler; I see what may be termed an aggregation, but not an association; there is as yet neither public good nor body politic. The man in question, even if he has enslaved half the world, is still only an individual; his interest, apart from that of others, is still a purely private interest. If this same man comes to die, his empire, after him, remains scattered and without unity, as an oak falls and dissolves into a heap of ashes when the fire has consumed it.

A people, says Grotius, can give itself to a king. Then, according to Grotius, a people is a people before it gives itself. The gift is itself a civil act, and implies public deliberation. It would be better, before examining the act by which a people gives itself to a king, to examine that by which it has become a people; for this act, being necessarily prior to the other, is the true foundation of society.

Indeed, if there were no prior convention, where, unless the election were unanimous, would be the obligation on the minority to submit to the choice of the majority? How have a hundred men who wish for a master the right to vote on behalf of ten who do not? The law of majority voting is itself something established by convention, and presupposes unanimity, on one occasion at least.

CHAPITRE V

QU'IL FAUT TOUJOURS REMONTER A UNE PREMIERE CONVENTIONQuand j'accorderais tout ce que j'ai réfuté jusqu'ici, les fauteurs du despotisme n'en seraient pas plus avancés. Il y aura toujours une grande différence entre soumettre une multitude et régir une société. Que des hommes épars soient successivement asservis à un seul, en quelque nombre qu'ils puissent être, je ne vois là qu'un maître et des esclaves, je n'y vois point un peuple et son chef; c'est si l'on veut une agrégation, mais non pas une association; il n'y a là ni bien public ni corps politique. Cet homme, eût-il asservi la moitié du monde, n'est toujours qu'un particulier; son intérêt, séparé de celui des autres, n'est toujours qu'un intérêt privé. Si ce même homme vient à périr, son empire après lui reste épars et sans liaison, comme un chêne se dissout et tombe en un tas de cendres, après que le feu l'a consumé.

Un peuple, dit Grotius, peut se donner à un roi. Selon Grotius un peuple est donc un peuple avant de se donner à un roi. Ce don même est un acte civil, il suppose une délibération publique. Avant donc que d'examiner l'acte par lequel un peuple élit un roi, il serait bon d'examiner l'acte par lequel un peuple est un peuple. Car cet acte étant nécessairement antérieur à l'autre est le vrai fondement de la société.

En effet, s'il n'y avait point de convention antérieure, où serait, à moins que l'élection ne fût unanime, l'obligation pour le petit nombre de se soumettre au choix du grand, et d'où cent qui veulent un maître ont-ils le droit de voter pour dix qui n'en veulent point? La loi de la pluralité des suffrages est elle-même un établissement de convention, et suppose au moins une fois l'unanimité.

CHAPTER VI THE SOCIAL COMPACT

I SUPPOSE men to have reached the point at which the obstacles in the way of their preservation in the state of nature show their power of resistance to be greater than the resources at the disposal of each individual for his maintenance in that state. That primitive condition can then subsist no longer; and the human race would perish unless it changed its manner of existence.

But, as men cannot engender new forces, but only unite and direct existing ones, they have no other means of preserving themselves than the formation, by aggregation, of a sum of forces great enough to overcome the resistance. These they have to bring into play by means of a single motive power, and cause to act in concert.

This sum of forces can arise only where several persons come together: but, as the force and liberty of each man are the chief instruments of his self-preservation, how can he pledge them without harming his own interests, and neglecting the care he owes to himself? This difficulty, in its bearing on my present subject, may be stated in the following terms:

"The problem is to find a form of association which will defend and protect with the whole common force the person and goods of each associate, and in which each, while uniting himself with all, may still obey himself alone, and remain as free as before." This is the fundamental problem of which the Social Contract provides the solution.

The clauses of this contract are so determined by the nature of the act that the slightest modification would make them vain and ineffective; so that, although they have perhaps never been formally set forth, they are everywhere the same and everywhere tacitly admitted and recognised, until, on the violation of the social compact, each regains his original rights and resumes his natural liberty, while losing the conventional liberty in favour of which he renounced it.

These clauses, properly understood, may be reduced to one — the total alienation of each associate, together with all his rights, to the whole community; for, in the first place, as each gives himself absolutely, the conditions are the same for all; and, this being so, no one has any interest in making them burdensome to others.

Moreover, the alienation being without reserve, the union is as perfect as it can be, and no associate has anything more to demand: for, if the individuals retained certain rights, as there would be no common superior to decide between them and the public, each, being on one point his own judge, would ask to be so on all; the state of nature would thus continue, and the association would necessarily become inoperative or tyrannical.

Finally, each man, in giving himself to all, gives himself to nobody; and as there is no associate over whom he does not acquire the same right as he yields others over himself, he gains an equivalent for everything he loses, and an increase of force for the preservation of what he has.

If then we discard from the social compact what is not of its essence, we shall find that it reduces itself to the following terms: Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will, and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.

At once, in place of the individual personality of each contracting party, this act of association creates a moral and collective body, composed of as many members as the assembly contains votes, and receiving from this act its unity, its common identity, its life and its will. This public person, so formed by the union of all other persons formerly took the name of city,4 and now takes that of Republic or body politic; it is called by its members State when passive. Sovereign when active, and Power when compared with others like itself. Those who are associated in it take collectively the name of people, and severally are called citizens, as sharing in the sovereign power, and subjects, as being under the laws of the State. But these terms are often confused and taken one for another: it is enough to know how to distinguish them when they are being used with precision.

CHAPITRE VI DU PACTE SOCIAL

Je suppose les hommes parvenus à ce point où les obstacles qui nuisent à leur conservation dans l'état de nature l'emportent par leur résistance sur les forces que chaque individu peut employer pour se maintenir dans cet état. Alors cet état primitif ne peut plus subsister, et le genre humain périrait s'il ne changeait sa manière d'être.

Or comme les hommes ne peuvent engendrer de nouvelles forces, mais seulement unir et diriger celles qui existent, ils n'ont plus d'autre moyen pour se conserver que de former par agrégation une somme de forces qui puisse l'emporter sur la résistance, de les mettre en jeu par un seul mobile et de les faire agir de concert.

Cette somme de forces ne peut naître que du concours de plusieurs: mais la force et la liberté de chaque homme étant les premiers instruments de sa conservation, comment les engagera-t-il sans se nuire, et sans négliger les soins qu'il se doit? Cette difficulté ramenée à mon sujet peut s'énoncer en ces termes:

"Trouver une forme d'association qui défende et protège de toute la force commune la personne et les biens de chaque associé, et par laquelle chacun s'unissant à tous n'obéisse pourtant qu'à lui-même et reste aussi libre qu'auparavant." Tel est le problème fondamental dont le contrat social donne la solution.

Les clauses de ce contrat sont tellement déterminées par la nature de l'acte que la moindre modification les rendrait vaines et de nul effet; en sorte que, bien qu'elles n'aient peut-être jamais été formellement énoncées, elles sont partout les mêmes, partout tacitement admises et reconnues; jusqu'à ce que, le pacte social étant violé, chacun rentre alors dans ses premiers droits et reprenne sa liberté naturelle, en perdant la liberté conventionnelle pour laquelle il y renonça.

Ces clauses bien entendues se réduisent toutes à une seule, savoir l'aliénation totale de chaque associé avec tous ses droits à toute la communauté. Car, premièrement, chacun se donnant tout entier, la condition est égale pour tous, et la condition étant égale pour tous, nul n'a intérêt de la rendre onéreuse aux autres.

De plus, l'aliénation se faisant sans réserve, l'union est aussi parfaite qu'elle ne peut l'être et nul associé n'a plus rien à réclamer: car s'il restait quelques droits aux particuliers, comme il n'y aurait aucun supérieur commun qui pût prononcer entre eux et le public, chacun étant en quelque point son propre juge prétendrait bientôt l'être en tous, l'état de nature subsisterait et l'association deviendrait nécessairement tyrannique ou vaine.

Enfin chacun se donnant à tous ne se donne à personne, et comme il n'y a pas un associé sur lequel on n'acquière le même droit qu'on lui cède sur soi, on gagne l'équivalent de tout ce qu'on perd, et plus de force pour conserver ce qu'on a.

Si donc on écarte du pacte social ce qui n'est pas de son essence, on trouvera qu'il se réduit aux termes suivants: Chacun de nous met en commun sa personne et toute sa puissance sous la suprême direction de la volonté générale; et nous recevons en corps chaque membre comme partie indivisible du tout.

A l'instant, au lieu de la personne particulière de chaque contractant, cet acte d'association produit un corps moral et collectif composé d'autant de membres que l'assemblée a de voix, lequel reçoit de ce même acte son unité, son moi commun, sa vie et sa volonté. Cette personne publique qui se forme ainsi par l'union de toutes les autres prenait autrefois le nom de Cité,4 et prend maintenant celui de République ou de corps politique, lequel est appelé par ses membres Etat quand il est passif, Souverain quand il est actif, Puissance en le comparant à ses semblables. A l'égard des associés ils prennent collectivement le nom de Peuple, et s'appellent en particulier citoyens comme participants à l'autorité souveraine, et sujets comme soumis aux lois de l'Etat. Mais ces termes se confondent souvent et se prennent l'un pour l'autre; il suffit de les savoir distinguer quand ils sont employés dans toute leur précision.

CHAPTER VII THE SOVEREIGN

THIS formula shows us that the act of association comprises a mutual undertaking between the public and the individuals, and that each individual, in making a contract, as we may say, with himself, is bound in a double capacity; as a member of the Sovereign he is bound to the individuals, and as a member of the State to the Sovereign. But the maxim of civil right, that no one is bound by undertakings made to himself, does not apply in this case; for there is a great difference between incurring an obligation to yourself and incurring one to a whole of which you form a part.

Attention must further be called to the fact that public deliberation, while competent to bind all the subjects to the Sovereign, because of the two different capacities in which each of them may be regarded, cannot, for the opposite reason, bind the Sovereign to itself; and that it is consequently against the nature of the body politic for the Sovereign to impose on itself a law which it cannot infringe. Being able to regard itself in only one capacity, it is in the position of an individual who makes a contract with himself; and this makes it clear that there neither is nor can be any kind of fundamental law binding on the body of the people — not even the social contract itself. This does not mean that the body politic cannot enter into undertakings with others, provided the contract is not infringed by them; for in relation to what is external to it, it becomes a simple being, an individual.

But the body politic or the Sovereign, drawing its being wholly from the sanctity of the contract, can never bind itself, even to an outsider, to do anything derogatory to the original act, for instance, to alienate any part of itself, or to submit to another Sovereign. Violation of the act by which it exists would be self-annihilation; and that which is itself nothing can create nothing.

As soon as this multitude is so united in one body, it is impossible to offend against one of the members without attacking the body, and still more to offend against the body without the members resenting it. Duty and interest therefore equally oblige the two contracting parties to give each other help; and the same men should seek to combine, in their double capacity, all the advantages dependent upon that capacity.

Again, the Sovereign, being formed wholly of the individuals who compose it, neither has nor can have any interest contrary to theirs; and consequently the sovereign power need give no guarantee to its subjects, because it is impossible for the body to wish to hurt all its members. We shall also see later on that it cannot hurt any in particular. The Sovereign, merely by virtue of what it is, is always what it should be.

This, however, is not the case with the relation of the subjects to the Sovereign, which, despite the common interest, would have no security that they would fulfil their undertakings, unless it found means to assure itself of their fidelity.

In fact, each individual, as a man, may have a particular will contrary or dissimilar to the general will which he has as a citizen. His particular interest may speak to him quite differently from the common interest: his absolute and naturally independent existence may make him look upon what he owes to the common cause as a gratuitous contribution, the loss of which will do less harm to others than the payment of it is burdensome to himself; and, regarding the moral person which constitutes the State as a persona ficta, because not a man, he may wish to enjoy the rights of citizenship without being ready to fulfil the duties of a subject. The continuance of such an injustice could not but prove the undoing of the body politic.

In order then that the social compact may not be an empty formula, it tacitly includes the undertaking, which alone can give force to the rest, that whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body. This means nothing less than that he will be forced to be free; for this is the condition which, by giving each citizen to his country, secures him against all personal dependence. In this lies the key to the working of the political machine; this alone legitimises civil undertakings, which, without it, would be absurd, tyrannical, and liable to the most frightful abuses.

CHAPITRE VII DU SOUVERAIN

On voit par cette formule que l'acte d'association renferme un engagement réciproque du public avec les particuliers, et que chaque individu, contractant, pour ainsi dire, avec lui-même, se trouve engagé sous un double rapport; savoir, comme membre du souverain envers les particuliers, et comme membre de l'Etat envers le souverain. Mais on ne peut appliquer ici la maxime du droit civil que nul n'est tenu aux engagements pris avec lui-même; car il y a bien de la différence entre s'obliger envers soi ou envers un tout dont on fait partie.

Il faut remarquer encore que la délibération publique, qui peut obliger tous les sujets envers le souverain, à cause des deux différents rapports sous lesquels chacun d'eux est envisagé, ne peut, par la raison contraire, obliger le souverain envers lui-même, et que, par conséquent, il est contre la nature du corps politique que le souverain s'impose une loi qu'il ne puisse enfreindre. Ne pouvant se considérer que sous un seul et même rapport il est alors dans le cas d'un particulier contractant avec soi-même: par où l'on voit qu'il n'y a ni ne peut y avoir nulle espèce de loi fondamentale obligatoire pour le corps du peuple, pas même le contrat social. Ce qui ne signifie pas que ce corps ne puisse fort bien s'engager envers autrui en ce qui ne déroge point à ce contrat; car à l'égard de l'étranger, il devient un être simple, un individu.

Mais le corps politique ou le souverain ne tirant son être que de la sainteté du contrat ne peut jamais s'obliger, même envers autrui, à rien qui déroge à cet acte primitif, comme d'aliéner quelque portion de lui-même ou de se soumettre à un autre souverain. Violer l'acte par lequel il existe serait s'anéantir, et ce qui n'est rien ne produit rien.

Sitôt que cette multitude est ainsi réunie en un corps, on ne peut offenser un des membres sans attaquer le corps; encore moins offenser le corps sans que les membres s'en ressentent. Ainsi le devoir et l'intérêt obligent également les deux parties contractantes à s'entraider mutuellement, et les mêmes hommes doivent chercher à réunir sous ce double rapport tous les avantages qui en dépendent.

Or le souverain n'étant formé que des particuliers qui le composent n'a ni ne peut avoir d'intérêt contraire au leur; par conséquent la puissance souveraine n'a nul besoin de garant envers les sujets, parce qu'il est impossible que le corps veuille nuire à tous ses membres, et nous verrons ci-après qu'il ne peut nuire à aucun en particulier. Le souverain, par cela seul qu'il est, est toujours tout ce qu'il doit être.

Mais il n'en est pas ainsi des sujets envers le souverain, auquel, malgré l'intérêt commun, rien ne répondrait de leurs engagements s'il ne trouvait des moyens de s'assurer de leur fidélité.

En effet chaque individu peut comme homme avoir une volonté particulière contraire ou dissemblable à la volonté générale qu'il a comme citoyen. Son intérêt particulier peut lui parler tout autrement que l'intérêt commun; son existence absolue et naturellement indépendante peut lui faire envisager ce qu'il doit à la cause commune comme une contribution gratuite, dont la perte sera moins nuisible aux autres que le payement n'en est onéreux pour lui, et regardant la personne morale qui constitue l'Etat comme un être de raison parce que ce n'est pas un homme, il jouirait des droits du citoyen sans vouloir remplir les devoirs du sujet, injustice dont le progrès causerait la ruine du corps politique.

Afin donc que le pacte social ne soit pas un vain formulaire, il renferme tacitement cet engagement qui seul peut donner de la force aux autres, que quiconque refusera d'obéir à la volonté générale y sera contraint par tout le corps: ce qui ne signifie autre chose sinon qu'on le forcera d'être libre; car telle est la condition qui donnant chaque citoyen à la Patrie le garantit de toute dépendance personnelle; condition qui fait l'artifice et le jeu de la machine politique, et qui seule rend légitimes les engagements civils, lesquels sans cela seraient absurdes, tyranniques, et sujets aux plus énormes abus.

CHAPTER VIII THE CIVIL STATE

THE passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable change in man, by substituting justice for instinct in his conduct, and giving his actions the morality they had formerly lacked. Then only, when the voice of duty takes the place of physical impulses and right of appetite, does man, who so far had considered only himself, find that he is forced to act on different principles, and to consult his reason before listening to his inclinations. Although, in this state, he deprives himself of some advantages which he got from nature, he gains in return others so great, his faculties are so stimulated and developed, his ideas so extended, his feelings so ennobled, and his whole soul so uplifted, that, did not the abuses of this new condition often degrade him below that which he left, he would be bound to bless continually the happy moment which took him from it for ever, and, instead of a stupid and unimaginative animal, made him an intelligent being and a man.

Let us draw up the whole account in terms easily commensurable. What man loses by the social contract is his natural liberty and an unlimited right to everything he tries to get and succeeds in getting; what he gains is civil liberty and the proprietorship of all he possesses. If we are to avoid mistake in weighing one against the other, we must clearly distinguish natural liberty, which is bounded only by the strength of the individual, from civil liberty, which is limited by the general will; and possession, which is merely the effect of force or the right of the first occupier, from property, which can be founded only on a positive title.

We might, over and above all this, add, to what man acquires in the civil state, moral liberty, which alone makes him truly master of himself; for the mere impulse of appetite is slavery, while obedience to a law which we prescribe to ourselves is liberty. But I have already said too much on this head, and the philosophical meaning of the word liberty does not now concern us.

CHAPITRE VIII DE L'ETAT CIVIL

Ce passage de l'état de nature à l'état civil produit dans l'homme un changement très remarquable, en substituant dans sa conduite la justice à l'instinct, et donnant à ses actions la moralité qui leur manquait auparavant. C'est alors seulement que la voix du devoir succédant à l'impulsion physique et le droit à l'appétit, l'homme, qui jusque-là n'avait regardé que lui-même, se voit forcé d'agir sur d'autres principes, et de consulter sa raison avant d'écouter ses penchants. Quoiqu'il se prive dans cet état de plusieurs avantages qu'il tient de la nature, il en regagne de si grands, ses facultés s'exercent et se développent, ses idées s'étendent, ses sentiments s'ennoblissent, son âme tout entière s'élève à tel point que si les abus de cette nouvelle condition ne le dégradaient souvent au-dessous de celle dont il est sorti, il devrait bénir sans cesse l'instant heureux qui l'en arracha pour jamais, et qui, d'un animal stupide et borné, fit un être intelligent et un homme.

Réduisons toute cette balance à des termes faciles à comparer. Ce que l'homme perd par le contrat social, c'est sa liberté naturelle et un droit illimité à tout ce qui le tente et qu'il peut atteindre; ce qu'il gagne, c'est la liberté civile et la propriété de tout ce qu'il possède. Pour ne pas se tromper dans ces compensations, il faut bien distinguer la liberté naturelle qui n'a pour bornes que les forces de l'individu, de la liberté civile qui est limitée par la volonté générale, et la possession qui n'est que l'effet de la force ou le droit du premier occupant, de la propriété qui ne peut être fondée que sur un titre positif.

On pourrait sur ce qui précède ajouter à l'acquis de l'état civil la liberté morale, qui seule rend l'homme vraiment maître de lui; car l'impulsion du seul appétit est esclavage, et l'obéissance à la loi qu'on s'est prescrite est liberté. Mais je n'en ai déjà que trop dit sur cet article, et le sens philosophique du mot liberté n'est pas ici de mon sujet.

CHAPTER IX REAL PROPERTY

EACH member of the community gives himself to it, at the moment of its foundation, just as he is, with all the resources at his command, including the goods he possesses. This act does not make possession, in changing hands, change its nature, and become property in the hands of the Sovereign; but, as the forces of the city are incomparably greater than those of an individual, public possession is also, in fact, stronger and more irrevocable, without being any more legitimate, at any rate from the point of view of foreigners. For the State, in relation to its members, is master of all their goods by the social contract, which, within the State, is the basis of all rights; but, in relation to other powers, it is so only by the right of the first occupier, which it holds from its members.

The right of the first occupier, though more real than the right of the strongest, becomes a real right only when the right of property has already been established. Every man has naturally a right to everything he needs; but the positive act which makes him proprietor of one thing excludes him from everything else. Having his share, he ought to keep to it, and can have no further right against the community. This is why the right of the first occupier, which in the state of nature is so weak, claims the respect of every man in civil society. In this right we are respecting not so much what belongs to another as what does not belong to ourselves.

In general, to establish the right of the first occupier over a plot of ground, the following conditions are necessary: first, the land must not yet be inhabited; secondly, a man must occupy only the amount he needs for his subsistence; and, in the third place, possession must be taken, not by an empty ceremony, but by labour and cultivation, the only sign of proprietorship that should be respected by others, in default of a legal title.

In granting the right of first occupancy to necessity and labour, are we not really stretching it as far as it can go? Is it possible to leave such a right unlimited? Is it to be enough to set foot on a plot of common ground, in order to be able to call yourself at once the master of it? Is it to be enough that a man has the strength to expel others for a moment, in order to establish his right to prevent them from ever returning? How can a man or a people seize an immense territory and keep it from the rest of the world except by a punishable usurpation, since all others are being robbed, by such an act, of the place of habitation and the means of subsistence which nature gave them in common? When Nunez Balboa, standing on the sea-shore, took possession of the South Seas and the whole of South America in the name of the crown of Castile, was that enough to dispossess all their actual inhabitants, and to shut out from them all the princes of the world? On such a showing, these ceremonies are idly multiplied, and the Catholic King need only take possession all at once, from his apartment, of the whole universe, merely making a subsequent reservation about what was already in the possession of other princes.

We can imagine how the lands of individuals, where they were contiguous and came to be united, became the public territory, and how the right of Sovereignty, extending from the subjects over the lands they held, became at once real and personal. The possessors were thus made more dependent, and the forces at their command used to guarantee their fidelity. The advantage of this does not seem to have been felt by ancient monarchs, who called themselves Kings of the Persians, Scythians, or Macedonians, and seemed to regard themselves more as rulers of men than as masters of a country. Those of the present day more cleverly call themselves Kings of France, Spain, England, etc.: thus holding the land, they are quite confident of holding the inhabitants.

The peculiar fact about this alienation is that, in taking over the goods of individuals, the community, so far from despoiling them, only assures them legitimate possession, and changes usurpation into a true right and enjoyment into proprietorship. Thus the possessors, being regarded as depositaries of the public good, and having their rights respected by all the members of the State and maintained against foreign aggression by all its forces, have, by a cession which benefits both the public and still more themselves, acquired, so to speak, all that they gave up. This paradox may easily be explained by the distinction between the rights which the Sovereign and the proprietor have over the same estate, as we shall see later on.

It may also happen that men begin to unite one with another before they possess anything, and that, subsequently occupying a tract of country which is enough for all, they enjoy it in common, or share it out among themselves, either equally or according to a scale fixed by the Sovereign. However the acquisition be made, the right which each individual has to his own estate is always subordinate to the right which the community has over all: without this, there would be neither stability in the social tie, nor real force in the exercise of Sovereignty.

I shall end this chapter and this book by remarking on a fact on which the whole social system should rest: i.e., that, instead of destroying natural inequality, the fundamental compact substitutes, for such physical inequality as nature may have set up between men, an equality that is moral and legitimate, and that men, who may be unequal in strength or intelligence, become every one equal by convention and legal right.5

CHAPITRE IX DU DOMAINE REEL

Chaque membre de la communauté se donne à elle au moment qu'elle se forme, tel qu'il se trouve actuellement, lui et toutes ses forces, dont les biens qu'il possède font partie. Ce n'est pas que par cet acte la possession change de nature en changeant de mains, et devienne propriété dans celles du souverain: Mais comme les forces de la cité sont incomparablement plus grandes que celles d'un particulier, la possession publique est aussi dans le fait plus forte et plus irrévocable, sans être plus légitime, au moins pour les étrangers. Car l'Etat à l'égard de ses membres est maître de tous leurs biens par le contrat social, qui dans l'Etat sert de base à tous les droits; mais il ne l'est à l'égard des autres puissances que par le droit de premier occupant qu'il tient des particuliers.

Le droit de premier occupant, quoique plus réel que celui du plus fort, ne devient un vrai droit qu'après l'établissement de celui de propriété. Tout homme a naturellement droit à tout ce qui lui est nécessaire; mais l'acte positif qui le rend propriétaire de quelque bien l'exclut de tout le reste. Sa part étant faite il doit s'y borner, et n'a plus aucun droit à la communauté. Voilà pourquoi le droit de premier occupant, si faible dans l'état de nature, est respectable à tout homme civil. On respecte moins dans ce droit ce qui est à autrui que ce qui n'est pas à soi.

En général, pour autoriser sur un terrain quelconque le droit de premier occupant, il faut les conditions suivantes. Premièrement que ce terrain ne soit encore habité par personne; secondement qu'on n'en occupe que la quantité dont on a besoin pour subsister; en troisième lieu qu'on en prenne possession, non par une vaine cérémonie, mais par le travail et la culture, seul signe de propriété qui au défaut de titres juridiques doive être respecté d'autrui.

En effet, accorder au besoin et au travail le droit de premier occupant, n'est-ce pas l'étendre aussi loin qu'il peut aller? Peut-on ne pas donner des bornes à ce droit? Suffira-t-il de mettre le pied sur un terrain commun pour s'en prétendre aussitôt le maître? Suffira-t-il d'avoir la force d'en écarter un moment les autres hommes pour leur ôter le droit d'y jamais revenir? Comment un homme ou un peuple peut-il s'emparer d'un territoire immense et en priver tout le genre humain autrement que par une usurpation punissable, puisqu'elle ôte au reste des hommes le séjour et les aliments que la nature leur donne en commun? Quand Nuñez Balboa prenait sur le rivage possession de la mer du Sud et de toute l'Amérique méridionale au nom de la couronne de Castille, était-ce assez pour en déposséder tous les habitants et en exclure tous les princes du monde? Sur ce pied-là ces cérémonies se multipliaient assez vainement, et le Roi catholique n'avait tout d'un coup qu'à prendre de son cabinet possession de tout l'univers; sauf à retrancher ensuite de son empire ce qui était auparavant possédé par les autres princes.

On conçoit comment les terres des particuliers réunies et contiguës deviennent le territoire public, et comment le droit de souveraineté s'étendant des sujets au terrain qu'ils occupent devient à la fois réel et personnel; ce qui met les possesseurs dans une plus grande dépendance, et fait de leurs forces mêmes les garants de leur fidélité. Avantage qui ne paraît pas avoir été bien senti des anciens monarques qui ne s'appelant que rois des Perses, des Scythes, des Macédoniens, semblaient se regarder comme les chefs des hommes plutôt que comme les maîtres du pays. Ceux d'aujourd'hui s'appellent plus habilement rois de France, d'Espagne, d'Angleterre, etc. En tenant ainsi le terrain, ils sont bien sûrs d'en tenir les habitants.

Ce qu'il y a de singulier dans cette aliénation, c'est que, loin qu'en acceptant les biens des particuliers la communauté les en dépouille, elle ne fait que leur en assurer la légitime possession, changer l'usurpation en un véritable droit, et la jouissance en propriété. Alors les possesseurs étant considérés comme dépositaires du bien public, leurs droits étant respectés de tous les membres de l'Etat et maintenus de toutes ses forces contre l'étranger, par une cession avantageuse au public et plus encore à eux-mêmes, ils ont, pour ainsi dire, acquis tout ce qu'ils ont donné. Paradoxe qui s'explique aisément par la distinction des droits que le souverain et le propriétaire ont sur le même fond, comme on verra ci-après.

Il peut arriver aussi que les hommes commencent à s'unir avant que de rien posséder, et que, s'emparant ensuite d'un terrain suffisant pour tous, ils en jouissent en commun, ou qu'ils le partagent entre eux, soit également soit selon des proportions établies par le souverain. De quelque manière que se fasse cette acquisition, le droit que chaque particulier a sur son propre fond est toujours subordonné au droit que la communauté a sur tous, sans quoi il n'y aurait ni solidité dans le lien social, ni force réelle dans l'exercice de la souveraineté.

Je terminerai ce chapitre et ce livre par une remarque qui doit servir de base à tout le système social; c'est qu'au lieu de détruire l'égalité naturelle, le pacte fondamental substitue au contraire une égalité morale et légitime à ce que la nature avait pu mettre d'inégalité physique entre les hommes, et que, pouvant être inégaux en force ou en génie, ils deviennent tous égaux par convention et de droit.5

1 "Learned inquiries into public right are often only the history of past abuses; and troubling to study them too deeply is a profitless infatuation" (Essay on the Interests of France in Relation to its Neighbours, by the Marquis d'Argenson). This is exactly what Grotius has done.

2 See a short treatise of Plutarch's entitled That Animals Reason.

3 The Romans, who understood and respected the right of war more than any other nation on earth, carried their scruples on this head so far that a citizen was not allowed to serve as a volunteer without engaging himself expressly against the enemy, and against such and such an enemy by name. A legion in which the younger Cato was seeing his first service under Popilius having been reconstructed, the elder Cato wrote to Popilius that, if he wished his son to continue serving under him, he must administer to him a new military oath, because, the first having been annulled, he was no longer able to bear arms against the enemy. The same Cato wrote to his son telling him to take great care not to go into battle before taking this new oath. I know that the siege of Clusium and other isolated events can be quoted against me; but I am citing laws and customs. The Romans are the people that least often transgressed its laws; and no other people has had such good ones.

1 "Les savantes recherches sur le droit public ne sont souvent que l'histoire des anciens abus, et on s'est entêté mal à propos quand on s'est donné la peine de les trop étudier." Traité manuscrit des intérêts de la Fr. avec ses voisins, par M. L. M. d'A. (Edition 1782: "Traité des intérêts de la Fr. avec ses voisins, par M. le Marquis d'Argenson, imprimé chez Rey à Amsterdam)" Voilà précisément ce qu'a fait Grotius. 2 Voyez un petit traité de Plutarque intitulé: Que les bêtes usent de la raison.

3 "Les Romains qui ont (mieux) entendu et plus respecté le droit de la guerre qu'aucune nation du monde portaient si loin le scrupule à cet égard qu'il n'était pas permis à un citoyen de servir comme volontaire sans s'être engagé expressément contre l'ennemi et nommément contre tel ennemi. Une légion où Caton le fils faisait ses premières armes sous Popilius allant été réformée, Caton le Père écrivit à Popilius que s'il voulait bien que son fils continuât de servir sous lui il fallait lui faire prêter un nouveau serment militaire, parce que le premier étant annulé il ne pouvait plus porter les armes contre l'ennemi. Et le même Caton écrivit à son fils de se bien garder de se présenter au combat qu'il n'eût prêté ce nouveau serment. Je sais qu'on pourra m'opposer le siège de Clusium et d'autres faits particuliers mais moi je cite des lois, des usages. Les Romains sont ceux qui ont le moins souvent transgressé leurs lois et ils sont les seuls qui en aient eu d'aussi belles." (Edition de 1782)

4 The real meaning of this word has been almost wholly lost in modern times; most people mistake a town for a city, and a townsman for a citizen. They do not know that houses make a town, but citizens a city. The same mistake long ago cost the Carthaginians dear. I have never read of the title of citizens being given to the subjects of any prince, not even the ancient Macedonians or the English of to-day, though they are nearer liberty than any one else. The French alone everywhere familiarly adopt the name of citizens, because, as can be seen from their dictionaries, they have no idea of its meaning; otherwise they would be guilty in usurping it, of the crime of lèse-majesté: among them, the name expresses a virtue, and not a right. When Bodin spoke of our citizens and townsmen, he fell into a bad blunder in taking the one class for the other. M. d'Alembert has avoided the error, and, in his article on Geneva, has clearly distinguished the four orders of men (or even five, counting mere foreigners) who dwell in our town, of which two only compose the Republic. No other French writer, to my knowledge, has understood the real meaning of the word citizen.

5 Under bad governments, this equality is only apparent and illusory: it serves only to-keep the pauper in his poverty and the rich man in the position he has usurped. In fact, laws are always of use to those who possess and harmful to those who have nothing: from which it follows that the social state is advantageous to men only when all have something and none too much.

4 Le vrai sens de ce mot s'est presque entièrement effacé chez les modernes; la plupart prennent une ville pour une cité et un bourgeois pour un citoyen. Ils ne savent pas que les maisons font la ville mais que les citoyens font la cité. Cette même erreur coûta cher autrefois aux Carthaginois. Je n'ai pas lu que le titre de Cives ait jamais été donné aux sujets d'aucun prince pas même anciennement aux Macédoniens, ni de nos jours aux Anglais, quoique plus près de la liberté que tous les autres. Les seuls Français prennent tout familièrement ce nom de citoyens, parce qu'ils n'en ont aucune véritable idée, comme on peut le voir dans leurs dictionnaires, sans quoi ils tomberaient en l'usurpant dans le crime de lèse-majesté: ce nom chez eux exprime une vertu et non pas un droit. Quand Bodin a voulu parler de nos citoyens et bourgeois, il a fait une lourde bévue en prenant les uns pour les autres. M. d'Alembert ne s'y est pas trompé, et a bien distingué dans son article Genève les quatre ordres d'hommes (même cinq en y comptant les simples étrangers) qui sont dans notre ville, et dont deux seulement composent la République. Nul autre auteur français, que je sache, n'a compris le vrai sens du mot citoyen. 5 Sous les mauvais gouvernements cette égalité n'est qu'apparente et illusoire, elle ne sert qu'à maintenir le pauvre dans sa misère et le riche dans son usurpation. Dans le fait les lois sons toujours utiles à ceux qui possèdent et nuisibles à ceux qui n'ont rien. D'où il suit que l'état social n'est avantageux aux hommes qu'autant qu'ils ont tous quelque chose et qu'aucun d'eux n'a rien de trop.

Continue on to Book Two

Return to the Table of Contents

Return to List of Authors and Books