SOCIAL CONTRACT

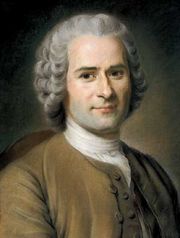

by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

1762

Translated by G. D. H. Cole

Book Four

BOOK IV FIRST CHAPTER

THAT THE GENERAL WILL IS INDESTRUCTIBLEAS long as several men in assembly regard themselves as a single body, they have only a single will which is concerned with their common preservation and general well-being. In this case, all the springs of the State are vigorous and simple and its rules clear and luminous; there are no embroilments or conflicts of interests; the common good is everywhere clearly apparent, and only good sense is needed to perceive it. Peace, unity and equality are the enemies of political subtleties. Men who are upright and simple are difficult to deceive because of their simplicity; lures and ingenious pretexts fail to impose upon them, and they are not even subtle enough to be dupes. When, among the happiest people in the world, bands of peasants are seen regulating affairs of State under an oak, and always acting wisely, can we help scorning the ingenious methods of other nations, which make themselves illustrious and wretched with so much art and mystery?

A State so governed needs very few laws; and, as it becomes necessary to issue new ones, the necessity is universally seen. The first man to propose them merely says what all have already felt, and there is no question of factions or intrigues or eloquence in order to secure the passage into law of what every one has already decided to do, as soon as he is sure that the rest will act with him.

Theorists are led into error because, seeing only States that have been from the beginning wrongly constituted, they are struck by the impossibility of applying such a policy to them. They make great game of all the absurdities a clever rascal or an insinuating speaker might get the people of Paris or London to believe. They do not know that Cromwell would have been put to "the bells" by the people of Berne, and the Duc de Beaufort on the treadmill by the Genevese.

But when the social bond begins to be relaxed and the State to grow weak, when particular interests begin to make themselves felt and the smaller societies to exercise an influence over the larger, the common interest changes and finds opponents: opinion is no longer unanimous; the general will ceases to be the will of all; contradictory views and debates arise; and the best advice is not taken without question.

Finally, when the State, on the eve of ruin, maintains only a vain, illusory and formal existence, when in every heart the social bond is broken, and the meanest interest brazenly lays hold of the sacred name of "public good," the general will becomes mute: all men, guided by secret motives, no more give their views as citizens than if the State had never been; and iniquitous decrees directed solely to private interest get passed under the name of laws.

Does it follow from this that the general will is exterminated or corrupted? Not at all: it is always constant, unalterable and pure; but it is subordinated to other wills which encroach upon its sphere. Each man, in detaching his interest from the common interest, sees clearly that he cannot entirely separate them; but his share in the public mishaps seems to him negligible beside the exclusive good he aims at making his own. Apart from this particular good, he wills the general good in his own interest, as strongly as any one else. Even in selling his vote for money, he does not extinguish in himself the general will, but only eludes it. The fault he commits is that of changing the state of the question, and answering something different from what he is asked. Instead of saying, by his vote, "It is to the advantage of the State," he says, "It is of advantage to this or that man or party that this or that view should prevail." Thus the law of public order in assemblies is not so much to maintain in them the general will as to secure that the question be always put to it, and the answer always given by it.

I could here set down many reflections on the simple right of voting in every act of Sovereignty a right which no one can take from the citizens and also on the right of stating views, making proposals, dividing and discussing, which the government is always most careful to leave solely to its members, but this important subject would need a treatise to itself, and it is impossible to say everything in a single work.

LIVRE IV CHAPITRE PREMIER

QUE LA VOLONTE GENERALE EST INDESTRUCTIBLETant que plusieurs hommes réunis se considèrent comme un seul corps, ils n'ont qu'une seule volonté, qui se rapporte à la commune conservation, et au bien-être général. Alors tous les ressorts de l'Etat sont vigoureux et simples, ses maximes sont claires et lumineuses, il n'a point d'intérêts embrouillés, contradictoires, le bien commun se montre partout avec évidence, et ne demande que du bon sens pour être aperçu. La paix, l'union, l'égalité sont ennemies des subtilités politiques. Les hommes droits et simples sont difficiles à tromper à cause de leur simplicité, les leurres, les prétextes raffinés ne leur en imposent point; ils ne sont pas même assez fins pour être dupes. Quand on voit chez le plus heureux peuple du monde des troupes de paysans régler les affaires de l'Etat sous un chêne et se conduire toujours sagement peut-on s'empêcher de mépriser les raffinements des autres nations, qui se rendent illustres et misérables avec tant d'art et de mystères?

Un Etat ainsi gouverné a besoin de très peu de lois, et à mesure qu'il devient nécessaire d'en promulguer de nouvelles, cette nécessité se voit universellement. Le premier qui les propose ne fait que dire ce que tous ont déjà senti, et il n'est question ni de brigues ni d'éloquence pour faire passer en loi ce que chacun a déjà résolu de faire, sitôt qu'il sera sûr que les autres le feront comme lui.

Ce qui trompe les raisonneurs c'est que ne voyant que des Etats mal constitués dès leur origine, ils sont frappés de l'impossibilité d'y maintenir une semblable police. Ils rient d'imaginer toutes les sottises qu'un fourbe adroit, un parleur insinuant pourrait persuader au peuple de Paris ou de Londres. Ils ne savent pas que Cromwell eût été mis aux sonnettes par le peuple de Berne, et le duc de Beaufort à la discipline par les Genevois.

Mais quand le noeud social commence à se relâcher et l'Etat à s'affaiblir, quand les intérêts particuliers commencent à se faire sentir et les petites sociétés à influer sur la grande, l'intérêt commun s'altère et trouve des opposants, l'unanimité ne règne plus dans les voix, la volonté générale n'est plus la volonté de tous, il s'élève des contradictions, des débats, et le meilleur avis ne passe point sans disputes.

Enfin quand l'Etat près de sa ruine ne subsiste plus que par une forme illusoire et vaine, que le lien social est rompu dans tous les cours, que le plus vil intérêt se pare effrontément du nom sacré du bien public alors la volonté générale devient muette, tous guidés par des motifs secrets n'opinent pas plus comme citoyens que si l'Etat n'eût jamais existé, et l'on fait passer faussement sous le nom de lois des décrets iniques qui n'ont pour but que l'intérêt particulier.

S'ensuit-il de là que la volonté générale soit anéantie ou corrompue? Non, elle est toujours constante, inaltérable et pure; mais elle est subordonnée à d'autres qui l'emportent sur elle. Chacun, détachant son intérêt de l'intérêt commun, voit bien qu'il ne peut l'en séparer tout à fait, mais sa part du mal public ne lui paraît rien, auprès du bien exclusif qu'il prétend s'approprier. Ce bien particulier excepté, il veut le bien général pour son propre intérêt tout aussi fortement qu'aucun autre. Même en vendant son suffrage à prix d'argent il n'éteint pas en lui la volonté générale, il l'élude. La faute qu'il commet est de changer l'état de la question et de répondre autre chose que ce qu'on lui demande: En sorte qu'au lieu de dire par son suffrage: Il est avantageux d l'Etat, il dit: Il est avantageux à tel homme ou à tel parti que tel ou tel avis passe. Ainsi la loi de l'ordre public dans les assemblées n'est pas tant d'y maintenir la volonté générale que de faire qu'elle soit toujours interrogée et qu'elle réponde toujours.

J'aurais ici bien des réflexions à faire sur le simple droit de voter dans tout acte de souveraineté; droit que rien ne peut ôter aux citoyens; et sur celui d'opiner, de proposer, de diviser, de discuter, que le gouvernement a toujours grand soin de ne laisser qu'à ses membres; mais cette importante matière demanderait un traité à part, et je ne puis tout dire dans celui-ci.

CHAPTER II

VOTINGIT may be seen, from the last chapter, that the way in which general business is managed may give a clear enough indication of the actual state of morals and the health of the body politic. The more concert reigns in the assemblies, that is, the nearer opinion approaches unanimity, the greater is the dominance of the general will. On the other hand, long debates, dissensions and tumult proclaim the ascendancy of particular interests and the decline of the State.

This seems less clear when two or more orders enter into the constitution, as patricians and plebeians did at Rome; for quarrels between these two orders often disturbed the comitia, even in the best days of the Republic. But the exception is rather apparent than real; for then, through the defect that is inherent in the body politic, there were, so to speak, two States in one, and what is not true of the two together is true of either separately. Indeed, even in the most stormy times, the plebiscita of the people, when the Senate did not interfere with them, always went through quietly and by large majorities. The citizens having but one interest, the people had but a single will.

At the other extremity of the circle, unanimity recurs; this is the case when the citizens, having fallen into servitude, have lost both liberty and will. Fear and flattery then change votes into acclamation; deliberation ceases, and only worship or malediction is left. Such was the vile manner in which the senate expressed its views under the Emperors. It did so sometimes with absurd precautions. Tacitus observes that, under Otho, the senators, while they heaped curses on Vitellius, contrived at the same time to make a deafening noise, in order that, should he ever become their master, he might not know what each of them had said.

On these various considerations depend the rules by which the methods of counting votes and comparing opinions should be regulated, according as the general will is more or less easy to discover, and the State more or less in its decline.

There is but one law which, from its nature, needs unanimous consent. This is the social compact; for civil association is the most voluntary of all acts. Every man being born free and his own master, no one, under any pretext whatsoever, can make any man subject without his consent. To decide that the son of a slave is born a slave is to decide that he is not born a man.

If then there are opponents when the social compact is made, their opposition does not invalidate the contract, but merely prevents them from being included in it. They are foreigners among citizens. When the State is instituted, residence constitutes consent; to dwell within its territory is to submit to the Sovereign.34

Apart from this primitive contract, the vote of the majority always binds all the rest. This follows from the contract itself. But it is asked how a man can be both free and forced to conform to wills that are not his own. How are the opponents at once free and subject to laws they have not agreed to?

I retort that the question is wrongly put. The citizen gives his consent to all the laws, including those which are passed in spite of his opposition, and even those which punish him when he dares to break any of them. The constant will of all the members of the State is the general will; by virtue of it they are citizens and free.35 When in the popular assembly a law is proposed, what the people is asked is not exactly whether it approves or rejects the proposal, but whether it is in conformity with the general will, which is their will. Each man, in giving his vote, states his opinion on that point; and the general will is found by counting votes. When therefore the opinion that is contrary to my own prevails, this proves neither more nor less than that I was mistaken, and that what I thought to be the general will was not so. If my particular opinion had carried the day I should have achieved the opposite of what was my will; and it is in that case that I should not have been free.

This presupposes, indeed, that all the qualities of the general will still reside in the majority: when they cease to do so, whatever side a man may take, liberty is no longer possible.

In my earlier demonstration of how particular wills are substituted for the general will in public deliberation, I have adequately pointed out the practicable methods of avoiding this abuse; and I shall have more to say of them later on. I have also given the principles for determining the proportional number of votes for declaring that will. A difference of one vote destroys equality; a single opponent destroys unanimity; but between equality and unanimity, there are several grades of unequal division, at each of which this proportion may be fixed in accordance with the condition and the needs of the body politic.

There are two general rules that may serve to regulate this relation. First, the more grave and important the questions discussed, the nearer should the opinion that is to prevail approach unanimity. Secondly, the more the matter in hand calls for speed, the smaller the prescribed difference in the numbers of votes may be allowed to become: where an instant decision has to be reached, a majority of one vote should be enough. The first of these two rules seems more in harmony with the laws, and the second with practical affairs. In any case, it is the combination of them that gives the best proportions for determining the majority necessary.

CHAPITRE II

DES SUFFRAGESOn voit par le chapitre précédent que la manière dont se traitent les affaires générales peut donner un indice assez sûr de l'état actuel des moeurs, et de la santé du corps politique. Plus le concert règne dans les assemblées, c'est-à-dire plus les avis approchent de l'unanimité, plus aussi la volonté générale est dominante; mais les longs débats, les dissensions, le tumulte, annoncent l'ascendant des intérêts particuliers et le déclin de l'Etat.

Ceci paraît moins évident quand deux ou plusieurs ordres entrent dans sa constitution, comme à Rome les patriciens et les plébéiens, dont les querelles troublèrent souvent les comices, même dans les plus beaux temps de la République; mais cette exception est plus apparente que réelle; car alors par le vice inhérent au corps politique on a, pour ainsi dire, deux Etats en un; ce qui n'est pas vrai des deux ensemble est vrai de chacun séparément. Et en effet dans les temps même les plus orageux les plébiscites du peuple, quand le Sénat ne s'en mêlait pas, passaient toujours tranquillement et à la grande pluralité des suffrages. Les citoyens n'ayant qu'un intérêt, le peuple n'avait qu'une volonté.

A l'autre extrémité du cercle l'unanimité revient. C'est quand les citoyens tombés dans la servitude n'ont plus ni liberté ni volonté. Alors la crainte et la flatterie changent en acclamations les suffrages; on ne délibère plus, on adore ou l'on maudit. Telle était la vile manière d'opiner du Sénat sous les Empereurs. Quelquefois cela se faisait avec des précautions ridicules: Tacite observe que sous Othon les sénateurs, accablant Vitellius d'exécrations, affectaient de faire en même temps un bruit épouvantable, afin que, si par hasard il devenait le maître, il ne pût savoir ce que chacun d'eux avait dit.

De ces diverses considérations naissent les maximes sur lesquelles on doit régler la manière de compter les voix et de comparer les avis, selon que la volonté générale est plus ou moins facile à connaître, et l'Etat plus ou moins déclinant.

Il n'y a qu'une seule loi qui par sa nature exige un consentement unanime. C'est le pacte social: car l'association civile est l'acte du monde le plus volontaire; tout homme étant né libre et maître de lui-même, nul ne peut, sous quelque prétexte que ce puisse être, l'assujettir sans son aveu. Décider que le fils d'une esclave naît esclave, c'est décider qu'il ne naît pas homme.

Si donc lors du pacte social il s'y trouve des opposants, leur opposition n'invalide pas le contrat, elle empêche seulement qu'ils n'y soient compris; ce sont des étrangers parmi les citoyens. Quand l'Etat est institué le consentement est dans la résidence; habiter le territoire c'est se soumettre à la souveraineté (Note 34) .

Hors ce contrat primitif, la voix du plus grand nombre oblige toujours tous les autres; c'est une suite du contrat même. Mais on demande comment un homme peut être libre, et forcé de se conformer à des volontés qui ne sont pas les siennes. Comment les opposants sont-ils libres et soumis à des lois auxquelles ils n'ont pas consenti?

Je réponds que la question est mal posée. Le citoyen consent à toutes les lois, même à celles qu'on passe malgré lui, et même à celles qui le punissent quand il ose en violer quelqu'une. La volonté constante de tous les membres de l'Etat est la volonté générale c'est par elle qu'ils sont citoyens et libres (Note 35) . Quand on propose une loi dans l'assemblée du peuple, ce qu'on leur demande n'est pas précisément s'ils approuvent la proposition ou s'ils la rejettent, mais si elle est conforme ou non à la volonté générale qui est la leur; chacun en donnant son suffrage dit son avis là-dessus, et du calcul des voix se tire la déclaration de la volonté générale. Quand donc l'avis contraire au mien l'emporte, cela ne prouve autre chose sinon que je m'étais trompé, et que ce que j'estimais être la volonté générale ne l'était pas. Si mon avis particulier l'eût emporté, j'aurais fait autre chose que ce que j'avais voulu, c'est alors que je n'aurais pas été libre.

Ceci suppose, il est vrai, que tous les caractères de la volonté générale sont encore dans la pluralité: quand ils cessent d'y être, quelque parti qu'on prenne il n'y a plus de liberté.

En montrant ci-devant comment on substituait des volontés particulières à la volonté générale dans les délibérations publiques, j'ai suffisamment indiqué les moyens praticables de prévenir cet abus; j'en parlerai encore ci-après. A l'égard du nombre proportionnel des suffrages pour déclarer cette volonté, j'ai aussi donné les principes sur lesquels on peut le déterminer. La différence d'une seule voix rompt l'égalité, un seul opposant rompt l'unanimité; mais entre l'unanimité et l'égalité il y a plusieurs partages inégaux, à chacun desquels on peut fixer ce nombre selon l'état et les besoins du corps politique.

Deux maximes générales peuvent servir à régler ces rapports: l'une, que plus les délibérations sont importantes et graves, plus l'avis qui l'emporte doit approcher de l'unanimité: l'autre, que plus l'affaire agitée exige de célérité, plus on doit resserrer la différence prescrite dans le partage des avis; dans les délibérations qu'il faut terminer sur-le-champ, l'excédent d'une seule voix doit suffire. La première de ces maximes paraît plus convenable aux lois, et la seconde aux affaires. Quoi qu'il en soit, c'est sur leur combinaison que s'établissent les meilleurs rapports qu'on peut donner à la pluralité pour prononcer.

CHAPTER III

ELECTIONSIN the elections of the prince and the magistrates, which are, as I have said, complex acts, there are two possible methods of procedure, choice and lot. Both have been employed in various republics, and a highly complicated mixture of the two still survives in the election of the Doge at Venice.

"Election by lot," says Montesquieu, "is democratic in nature."E3 I agree that it is so; but in what sense? "The lot," he goes on, "is a way of making choice that is unfair to nobody; it leaves each citizen a reasonable hope of serving his country." These are not reasons.

If we bear in mind that the election of rulers is a function of government, and not of Sovereignty, we shall see why the lot is the method more natural to democracy, in which the administration is better in proportion as the number of its acts is small.

In every real democracy, magistracy is not an advantage, but a burdensome charge which cannot justly be imposed on one individual rather than another. The law alone can lay the charge on him on whom the lot falls. For, the conditions being then the same for all, and the choice not depending on any human will, there is no particular application to alter the universality of the law.

In an aristocracy, the prince chooses the prince, the government is preserved by itself, and voting is rightly ordered.

The instance of the election of the Doge of Venice confirms, instead of destroying, this distinction; the mixed form suits a mixed government. For it is an error to take the government of Venice for a real aristocracy. If the people has no share in the government, the nobility is itself the people. A host of poor Barnabotes never gets near any magistracy, and its nobility consists merely in the empty title of Excellency, and in the right to sit in the Great Council. As this Great Council is as numerous as our General Council at Geneva, its illustrious members have no more privileges than our plain citizens. It is indisputable that, apart from the extreme disparity between the two republics, the bourgeoisie of Geneva is exactly equivalent to the patriciate of Venice; our natives and inhabitants correspond to the townsmen and the people of Venice; our peasants correspond to the subjects on the mainland; and, however that republic be regarded, if its size be left out of account, its government is no more aristocratic than our own. The whole difference is that, having no life-ruler, we do not, like Venice, need to use the lot.

Election by lot would have few disadvantages in a real democracy, in which, as equality would everywhere exist in morals and talents as well as in principles and fortunes, it would become almost a matter of indifference who was chosen. But I have already said that a real democracy is only an ideal.

When choice and lot are combined, positions that require special talents, such as military posts, should be filled by the former; the latter does for cases, such as judicial offices, in which good sense, justice, and integrity are enough, because in a State that is well constituted, these qualities are common to all the citizens.

Neither lot nor vote has any place in monarchical government. The monarch being by right sole prince and only magistrate, the choice of his lieutenants belongs to none but him. When the Abbé de Saint-Pierre proposed that the Councils of the King of France should be multiplied, and their members elected by ballot, he did not see that he was proposing to change the form of government.

I should now speak of the methods of giving and counting opinions in the assembly of the people; but perhaps an account of this aspect of the Roman constitution will more forcibly illustrate all the rules I could lay down. It is worth the while of a judicious reader to follow in some detail the working of public and private affairs in a Council consisting of two hundred thousand men.

CHAPITRE III

DES ELECTIONSA l'égard des élections du prince et des magistrats, qui sont, comme je l'ai dit, des actes complexes, il y a deux voies pour y procéder; savoir, le choix et le sort. L'une et l'autre ont été employées en diverses républiques, et l'on voit encore actuellement un mélange très compliqué des deux dans l'élection du doge de Venise.

Le suffrage par le sort, dit Montesquieu, est de la nature de la démocratie. J'en conviens, mais comment cela? Le sort, continue-t-il, est une façon d'élire qui n'afflige personne; il laisse à chaque citoyen une espérance raisonnable de servir la patrie. Ce ne sont pas là des raisons.

Si l'on fait attention que l'élection des chefs est une fonction du gouvernement et non de la souveraineté, on verra pourquoi la voie du sort est plus dans la nature de la démocratie, où l'administration est d'autant meilleure que les actes en sont moins multipliés.

Dans toute véritable démocratie la magistrature n'est pas un avantage mais une charge onéreuse, qu'on ne peut justement imposer à un particulier plutôt qu'à un autre. La loi seule peut imposer cette charge à celui sur qui le sort tombera. Car alors la condition étant égale pour tous, et le choix ne dépendant d'aucune volonté humaine, il n'y a point d'application particulière qui altère l'universalité de la loi.

Dans l'aristocratie le prince choisit le prince, le gouvernement se conserve par lui-même, et c'est là que les suffrages sont bien placés.

L'exemple de l'élection du doge de Venise confirme cette distinction loin de la détruire. Cette forme mêlée convient dans un gouvernement mixte. Car c'est une erreur de prendre le gouvernement de Venise pour une véritable aristocratie. Si le peuple n'y a nulle part au gouvernement, la noblesse y est peuple elle-même. Une multitude de pauvres Barnabotes n'approcha jamais d'aucune magistrature, et n'a de sa noblesse que le vain titre d'Excellence et le droit d'assister au grand conseil. Ce grand conseil étant aussi nombreux que notre conseil général à Genève, ses illustres membres n'ont pas plus de privilèges que nos simples citoyens. Il est certain qu'ôtant l'extrême disparité des deux républiques, la bourgeoisie de Genève représente exactement le patriciat vénitien, nos natifs et habitants représentent les citadins et le peuple de Venise, nos paysans représentent les sujets de terre ferme: enfin de quelque manière que l'on considère cette république, abstraction faite de sa grandeur, son gouvernement n'est pas plus aristocratique que le nôtre. Toute la différence est que n'ayant aucun chef à vie nous n'avons pas le même besoin du sort.

Les élections par sort auraient peu d'inconvénient dans une véritable démocratie où tout étant égal, aussi bien par les moeurs et par les talents que par les maximes et par la fortune, le choix deviendrait presque indifférent. Mais j'ai déjà dit qu'il n'y avait point de véritable démocratie.

Quand le choix et le sort se trouvent mêlés, le premier doit remplir les places qui demandent des talents propres, telles que les emplois militaires; l'autre convient à celles où suffisent le bon sens, la justice, l'intégrité, telles que les charges de judicature; parce que dans un Etat bien constitué ces qualités sont communes à tous les citoyens.

Le sort ni les suffrages n'ont aucun lieu dans le gouvernement monarchique. Le monarque étant de droit seul prince et magistrat unique, le choix de ses lieutenants n'appartient qu'à lui. Quand l'abbé de Saint-Pierre proposait de multiplier les conseils du Roi de France et d'en élire les membres par scrutin, il ne voyait pas qu'il proposait de changer la forme du gouvernement.

Il me resterait à parler de la manière de donner et de recueillir les voix dans l'assemblée du peuple; mais peut-être l'historique de la police romaine à cet égard expliquera-t-il plus sensiblement toutes les maximes que je pourrais établir. Il n'est pas indigne d'un lecteur judicieux de voir un peu en détail comment se traitaient les affaires publiques et particulières dans un conseil de deux cent mille hommes.

CHAPTER IV

THE ROMAN COMITIAWE are without well-certified records of the first period of Rome's existence; it even appears very probable that most of the stories told about it are fables; indeed, generally speaking, the most instructive part of the history of peoples, that which deals with their foundation, is what we have least of. Experience teaches us every day what causes lead to the revolutions of empires; but, as no new peoples are now formed, we have almost nothing beyond conjecture to go upon in explaining how they were created.

The customs we find established show at least that these customs had an origin. The traditions that go back to those origins, that have the greatest authorities behind them, and that are confirmed by the strongest proofs, should pass for the most certain. These are the rules I have tried to follow in inquiring how the freest and most powerful people on earth exercised its supreme power.

After the foundation of Rome, the new-born republic, that is, the army of its founder, composed of Albans, Sabines and foreigners, was divided into three classes, which, from this division, took the name of tribes. Each of these tribes was subdivided into ten curiæ, and each curia into decuriæ, headed by leaders called curiones and decuriones.

Besides this, out of each tribe was taken a body of one hundred Equites or Knights, called a century, which shows that these divisions, being unnecessary in a town, were at first merely military. But an instinct for greatness seems to have led the little township of Rome to provide itself in advance with a political system suitable for the capital of the world.

Out of this original division an awkward situation soon arose. The tribes of the Albans (Ramnenses) and the Sabines (Tatienses) remained always in the same condition, while that of the foreigners (Luceres) continually grew as more and more foreigners came to live at Rome, so that it soon surpassed the others in strength. Servius remedied this dangerous fault by changing the principle of cleavage, and substituting for the racial division, which he abolished, a new one based on the quarter of the town inhabited by each tribe. Instead of three tribes he created four, each occupying and named after one of the hills of Rome. Thus, while redressing the inequality of the moment, he also provided for the future; and in order that the division might be one of persons as well as localities, he forbade the inhabitants of one quarter to migrate to another, and so prevented the mingling of the races.

He also doubled the three old centuries of Knights and added twelve more, still keeping the old names, and by this simple and prudent method, succeeded in making a distinction between the body of Knights, and the people, without a murmur from the latter.

To the four urban tribes Servius added fifteen others called rural tribes, because they consisted of those who lived in the country, divided into fifteen cantons. Subsequently, fifteen more were created, and the Roman people finally found itself divided into thirty-five tribes, as it remained down to the end of the Republic.

The distinction between urban and rural tribes had one effect which is worth mention, both because it is without parallel elsewhere, and because to it Rome owed the preservation of her morality and the enlargement of her empire. We should have expected that the urban tribes would soon monopolise power and honours, and lose no time in bringing the rural tribes into disrepute; but what happened was exactly the reverse. The taste of the early Romans for country life is well known. This taste they owed to their wise founder, who made rural and military labours go along with liberty, and, so to speak, relegated to the town arts, crafts, intrigue, fortune and slavery.

Since therefore all Rome's most illustrious citizens lived in the fields and tilled the earth, men grew used to seeking there alone the mainstays of the republic. This condition, being that of the best patricians, was honoured by all men; the simple and laborious life of the villager was preferred to the slothful and idle life of the bourgeoisie of Rome; and he who, in the town, would have been but a wretched proletarian, became, as a labourer in the fields, a respected citizen. Not without reason, says Varro, did our great-souled ancestors establish in the village the nursery of the sturdy and valiant men who defended them in time of war and provided for their sustenance in time of peace. Pliny states positively that the country tribes were honoured because of the men of whom they were composed; while cowards men wished to dishonour were transferred, as a public disgrace, to the town tribes. The Sabine Appius Claudius, when he had come to settle in Rome, was loaded with honours and enrolled in a rural tribe, which subsequently took his family name. Lastly, freedmen always entered the urban, arid never the rural, tribes: nor is there a single example, throughout the Republic, of a freedman, though he had become a citizen, reaching any magistracy.

This was an excellent rule; but it was carried so far that in the end it led to a change and certainly to an abuse in the political system.

First the censors, after having for a long time claimed the right of transferring citizens arbitrarily from one tribe to another, allowed most persons to enrol themselves in whatever tribe they pleased. This permission certainly did no good, and further robbed the censorship of one of its greatest resources. Moreover, as the great and powerful all got themselves enrolled in the country tribes, while the freedmen who had become citizens remained with the populace in the town tribes, both soon ceased to have any local or territorial meaning, and all were so confused that the members of one could not be told from those of another except by the registers; so that the idea of the word tribe became personal instead of real, or rather came to be little more than a chimera.

It happened in addition that the town tribes, being more on the spot, were often the stronger in the comitia and sold the State to those who stooped to buy the votes of the rabble composing them.

As the founder had set up ten curiæ in each tribe, the whole Roman people, which was then contained within the walls, consisted of thirty curiæ, each with its temples, its gods, its officers, its priests and its festivals, which were called compitalia and corresponded to the paganalia, held in later times by the rural tribes.

When Servius made his new division, as the thirty curiæ could not be shared equally between his four tribes, and as he was unwilling to interfere with them, they became a further division of the inhabitants of Rome, quite independent of the tribes: but in the case of the rural tribes and their members there was no question of curiæ, as the tribes had then become a purely civil institution, and, a new system of levying troops having been introduced, the military divisions of Romulus were superfluous. Thus, although every citizen was enrolled in a tribe, there were very many who were not members of a curia.

Servius made yet a third division, quite distinct from the two we have mentioned, which became, in its effects, the most important of all. He distributed the whole Roman people into six classes, distinguished neither by place nor by person, but by wealth; the first classes included the rich, the last the poor, and those between persons of moderate means. These six classes were subdivided into one hundred and ninety-three other bodies, called centuries, which were so divided that the first class alone comprised more than half of them, while the last comprised only one. Thus the class that had the smallest number of members had the largest number of centuries, and the whole of the last class only counted as a single subdivision, although it alone included more than half the inhabitants of Rome.

In order that the people might have the less insight into the results of this arrangement, Servius tried to give it a military tone: in the second class he inserted two centuries of armourers, and in the fourth two of makers of instruments of war: in each class, except the last, he distinguished young and old, that is, those who were under an obligation to bear arms and those whose age gave them legal exemption. It was this distinction, rather than that of wealth, which required frequent repetition of the census or counting. Lastly, he ordered that the assembly should be held in the Campus Martius, and that all who were of age to serve should come there armed.

The reason for his not making in the last class also the division of young and old was that the populace, of whom it was composed, was not given the right to bear arms for its country: a man had to possess a hearth to acquire the right to defend it, and of all the troops of beggars who to-day lend lustre to the armies of kings, there is perhaps not one who would not have been driven with scorn out of a Roman cohort, at a time when soldiers were the defenders of liberty.

In this last class, however, proletarians were distinguished from capite censi. The former, not quite reduced to nothing, at least gave the State citizens, and sometimes, when the need was pressing, even soldiers. Those who had nothing at all, and could be numbered only by counting heads, were regarded as of absolutely no account, and Marius was the first who stooped to enrol them.

Without deciding now whether this third arrangement was good or bad in itself, I think I may assert that it could have been made practicable only by the simple morals, the disinterestedness, the liking for agriculture and the scorn for commerce and for love of gain which characterised the early Romans. Where is the modern people among whom consuming greed, unrest, intrigue, continual removals, and perpetual changes of fortune, could let such a system last for twenty years without turning the State upside down? We must indeed observe that morality and the censorship, being stronger than this institution, corrected its defects at Rome, and that the rich man found himself degraded to the class of the poor for making too much display of his riches.

From all this it is easy to understand why only five classes are almost always mentioned, though there were really six. The sixth, as it furnished neither soldiers to the army nor votes in the Campus Martius,36 and was almost without function in the State, was seldom regarded as of any account.

These were the various ways in which the Roman people was divided. Let us now see the effect on the assemblies. When lawfully summoned, these were called comitia: they were usually held in the public square at Rome or in the Campus Martius, and were distinguished as comitia curiata, comitia centuriata, and comitia tributa, according to the form under which they were convoked. The comitia curiata were founded by Romulus; the centuriata by Servius; and the tributa by the tribunes of the people. No law received its sanction and no magistrate was elected, save in the comitia; and as every citizen was enrolled in a curia, a century, or a tribe, it follows that no citizen was excluded from the right of voting, and that the Roman people was truly sovereign both de jure and de facto.

For the comitia to be lawfully assembled, and for their acts to have the force of law, three conditions were necessary. First, the body or magistrate convoking them had to possess the necessary authority; secondly, the assembly had to be held on a day allowed by law; and thirdly, the auguries had to be favourable.

The reason for the first regulation needs no explanation; the second is a matter of policy. Thus, the comitia might not be held on festivals or market-days, when the country-folk, coming to Rome on business, had not time to spend the day in the public square. By means of the third, the senate held in check the proud and restive people, and meetly restrained the ardour of seditious tribunes, who, however, found more than one way of escaping this hindrance.

Laws and the election of rulers were not the only questions submitted to the judgment of the comitia: as the Roman people had taken on itself the most important functions of government, it may be said that the lot of Europe was regulated in its assemblies. The variety of their objects gave rise to the various forms these took, according to the matters on which they had to pronounce.

In order to judge of these various forms, it is enough to compare them. Romulus, when he set up curia, had in view the checking of the senate by the people, and of the people by the senate, while maintaining his ascendancy over both alike. He therefore gave the people, by means of this assembly, all the authority of numbers to balance that of power and riches, which he left to the patricians. But, after the spirit of monarchy, he left all the same a greater advantage to the patricians in the influence of their clients on the majority of votes. This excellent institution of patron and client was a masterpiece of statesmanship and humanity without which the patriciate, being flagrantly in contradiction to the republican spirit, could not have survived. Rome alone has the honour of having given to the world this great example, which never led to any abuse, and yet has never been followed.

As the assemblies by curiæ persisted under the kings till the time of Servius, and the reign of the later Tarquin was not regarded as legitimate, royal laws were called generally leges curiatæ.

Under the Republic, the curiæ, still confined to the four urban tribes, and including only the populace of Rome, suited neither the senate, which led the patricians, nor the tribunes, who, though plebeians, were at the head of the well-to-do citizens. They therefore fell into disrepute, and their degradation was such, that thirty lictors used to assemble and do what the comitia curiata should have done.

The division by centuries was so favourable to the aristocracy that it is hard to see at first how the senate ever failed to carry the day in the comitia bearing their name, by which the consuls, the censors and the other curule magistrates were elected. Indeed, of the hundred and ninety-three centuries into which the six classes of the whole Roman people were divided, the first class contained ninety-eight; and, as voting went solely by centuries, this class alone had a majority over all the rest. When all these centuries were in agreement, the rest of the votes were not even taken; the decision of the smallest number passed for that of the multitude, and it may be said that, in the comitia centuriata, decisions were regulated far more by depth of purses than by the number of votes.

But this extreme authority was modified in two ways. First, the tribunes as a rule, and always a great number of plebeians, belonged to the class of the rich, and so counterbalanced the influence of the patricians in the first class.

The second way was this. Instead of causing the centuries to vote throughout in order, which would have meant beginning always with the first, the Romans always chose one by lot which proceeded alone to the election; after this all the centuries were summoned another day according to their rank, and the same election was repeated, and as a rule confirmed. Thus the authority of example was taken away from rank, and given to the lot on a democratic principle.

From this custom resulted a further advantage. The citizens from the country had time, between the two elections, to inform themselves of the merits of the candidate who had been provisionally nominated, and did not have to vote without knowledge of the case. But, under the pretext of hastening matters, the abolition of this custom was achieved, and both elections were held on the same day.

The comitia tributa were properly the council of the Roman people. They were convoked by the tribunes alone; at them the tribunes were elected and passed their plebiscita. The senate not only had no standing in them, but even no right to be present; and the senators, being forced to obey laws on which they could not vote, were in this respect less free than the meanest citizens. This injustice was altogether ill-conceived, and was alone enough to invalidate the decrees of a body to which all its members were not admitted. Had all the patricians attended the comitia by virtue of the right they had as citizens, they would not, as mere private individuals, have had any considerable influence on a vote reckoned by counting heads, where the meanest proletarian was as good as the princeps senatus.

It may be seen, therefore, that besides the order which was achieved by these various ways of distributing so great a people and taking its votes, the various methods were not reducible to forms indifferent in themselves, but the results of each were relative to the objects which caused it to be preferred.

Without going here into further details, we may gather from what has been said above that the comitia tributa were the most favourable to popular government, and the comitia centuriata to aristocracy. The comitia curiata, in which the populace of Rome formed the majority, being fitted only to further tyranny and evil designs, naturally fell into disrepute, and even seditious persons abstained from using a method which too clearly revealed their projects. It is indisputable that the whole majesty of the Roman people lay solely in the comitia centuriata, which alone included all; for the comitia curiata excluded the rural tribes, and the comitia tributa the senate and the patricians.

As for the method of taking the vote, it was among the ancient Romans as simple as their morals, although not so simple as at Sparta. Each man declared his vote aloud, and a clerk duly wrote it down; the majority in each tribe determined the vote of the tribe, the majority of the tribes that of the people, and so with curiæ and centuries. This custom was good as long as honesty was triumphant among the citizens, and each man was ashamed to vote publicly in favour of an unjust proposal or an unworthy subject; but, when the people grew corrupt and votes were bought, it was fitting that voting should be secret in order that purchasers might be restrained by mistrust, and rogues be given the means of not being traitors.

I know that Cicero attacks this change, and attributes partly to it the ruin of the Republic. But though I feel the weight Cicero's authority must carry on such a point, I cannot agree with him; I hold, on the contrary, that, for want of enough such changes, the destruction of the State must be hastened. Just as the regimen of health does not suit the sick, we should not wish to govern a people that has been corrupted by the laws that a good people requires. There is no better proof of this rule than the long life of the Republic of Venice, of which the shadow still exists, solely because its laws are suitable only for men who are wicked.

The citizens were provided, therefore, with tablets by means of which each man could vote without any one knowing how he voted: new methods were also introduced for collecting the tablets, for counting voices, for comparing numbers, etc.; but all these precautions did not prevent the good faith of the officers charged with these functions37 from being often suspect. Finally, to prevent intrigues and trafficking in votes, edicts were issued; but their very number proves how useless they were.

Towards the close of the Republic, it was often necessary to have recourse to extraordinary expedients in order to supplement the inadequacy of the laws. Sometimes miracles were supposed; but this method, while it might impose on the people, could not impose on those who governed. Sometimes an assembly was hastily called together, before the candidates had time to form their factions: sometimes a whole sitting was occupied with talk, when it was seen that the people had been won over and was on the point of taking up a wrong position. But in the end ambition eluded all attempts to check it; and the most incredible fact of all is that, in the midst of all these abuses, the vast people, thanks to its ancient regulations, never ceased to elect magistrates, to pass laws, to judge cases, and to carry through business both public and private, almost as easily as the senate itself could have done.

CHAPITRE IV

DES COMICES ROMAINSNous n'avons nuls monuments bien assurés des premiers temps de Rome; il y a même grande apparence que la plupart des choses qu'on en débite sont des fables (Note 36) ; et en général la partie la plus instructive des annales des peuples, qui est l'histoire de leur établissement, est celle qui nous manque le plus. L'expérience nous apprend tous les jours de quelles causes naissent les révolutions des empires; mais comme il ne se forme plus de peuples, nous n'avons guère que des conjectures pour expliquer comment ils se sont formés.

Les usages qu'on trouve établis attestent au moins qu'il y eut une origine à ces usages. Des traditions qui remontent à ces origines, celles qu'appuient les plus grandes autorités et que de plus fortes raisons confirment doivent passer pour les plus certaines. Voilà les maximes que j'ai tâché de suivre en recherchant comment le plus libre et le plus puissant peuple de la terre exerçait son pouvoir suprême.

Après la fondation de Rome la République naissante, c'est-à-dire l'armée du fondateur, composée d'Albains, de Sabins, et d'étrangers, fut divisée en trois classes, qui de cette division prirent le nom de tribus. Chacune de ces tribus fut subdivisée en dix curies, et chaque curie en décuries, à la tête desquelles on mit des chefs appelés curions et décurions.

Outre cela on tira de chaque tribu un corps de cent cavaliers ou chevaliers, appelé centurie: par où l'on voit que ces divisions, peu nécessaires dans un bourg, n'étaient d'abord que militaires. Mais il semble qu'un instinct de grandeur portait la petite ville de Rome à se donner d'avance une police convenable à la capitale du monde.

De ce premier partage résulta bientôt un inconvénient. C'est que la tribu des Albains (Note 37) et celle des Sabins (Note 38) restant toujours au même état, tandis que celle des étrangers (Note 39) croissait sans cesse par le concours perpétuel de ceux-ci, cette dernière ne tarda pas à surpasser les deux autres. Le remède que Servius trouva à ce dangereux abus fut de changer la division, et à celle des races, qu'il abolit, d'en substituer une autre tirée des lieux de la ville occupés par chaque tribu. Au lieu de trois tribus il en fit quatre; chacune desquelles occupait une des collines de Rome et en portait le nom. Ainsi remédiant à l'inégalité présente il la prévint encore pour l'avenir; et afin que cette division ne fût pas seulement de lieux mais d'hommes il défendit aux habitants d'un quartier de passer dans un autre, ce qui empêcha les races de se confondre.

Il doubla aussi les trois anciennes centuries de cavalerie et y en ajouta douze autres, mais toujours sous les anciens noms; moyen simple et judicieux par lequel il acheva de distinguer le corps des chevaliers de celui du peuple, sans faire murmurer ce dernier.

A ces quatre tribus urbaines Servius en ajouta quinze autres appelées tribus rustiques, parce qu'elles étaient formées des habitants de la campagne, partagés en autant de cantons. Dans la suite on en fit autant de nouvelles, et le peuple romain se trouva enfin divisé en trente-cinq tribus; nombre auquel elles restèrent fixées jusqu'à la fin de la République.

De cette distinction des tribus de la ville et des tribus de la campagne résulta un effet digne d'être observé, parce qu'il n'y en a point d'autre exemple, et que Rome lui dut à la fois la conservation de ses moeurs et l'accroissement de son empire. On croirait que les tribus urbaines s'arrogèrent bientôt la puissance et les honneurs, et ne tardèrent pas d'avilir les tribus rustiques; ce fut tout le contraire. On connaît le goût des premiers Romains pour la vie champêtre. Ce goût leur venait du sage instituteur qui unit à la liberté les travaux rustiques et militaires, et relégua pour ainsi dire à la ville les arts, les métiers, l'intrigue, la fortune et l'esclavage.

Ainsi tout ce que Rome avait d'illustre vivant aux champs et cultivant les terres, on s'accoutuma à ne chercher que là les soutiens de la République. Cet état étant celui des plus dignes patriciens fut honoré de tout le monde: la vie simple et laborieuse des villageois fut préférée à la vie oisive et lâche des bourgeois de Rome, et tel n'eût été qu'un malheureux prolétaire à la ville qui, laboureur aux champs, devint un citoyen respecté. Ce n'est pas sans raison, disait Varron, que nos magnanimes ancêtres établirent au village la pépinière de ces robustes et vaillants hommes qui les défendaient en temps de guerre et les nourrissaient en temps de paix. Pline dit positivement que les tribus des champs étaient honorées à cause des hommes qui les composaient; au lieu qu'on transférait par ignominie dans celles de la ville les lâches qu'on voulait avilir. Le Sabin Appius Claudius étant venu s'établir à Rome y fut comblé d'honneurs et inscrit dans une tribu rustique qui prit dans la suite le nom de sa famille. Enfin les affranchis entraient tous dans les tribus urbaines, jamais dans les rurales; et il n'y a pas durant toute la République un seul exemple d'aucun de ces affranchis parvenu à aucune magistrature, quoique devenu citoyen.

Cette maxime était excellente; mais elle fut poussée si loin qu'il en résulta enfin un changement et certainement un abus dans la police.

Premièrement, les censeurs, après s'être arrogé longtemps le droit de transférer arbitrairement les citoyens d'une tribu à l'autre, permirent à la plupart de se faire inscrire dans celle qui leur plaisait; permission qui sûrement n'était bonne à rien, et ôtait un des grands ressorts de la censure. De plus, les grands et les puissants se faisant tous inscrire dans les tribus de la campagne, et les affranchis devenus citoyens restant avec la populace dans celles de la ville, les tribus en général n'eurent plus de lieu ni de territoire; mais toutes se trouvèrent tellement mêlées qu'on ne pouvait plus discerner les membres de chacune que par les registres, en sorte que l'idée du mot tribu passa ainsi du réel au personnel ou, plutôt, devint presque une chimère.

Il arriva encore que les tribus de la ville, étant plus à portée, se trouvèrent souvent les plus fortes dans les comices, et vendirent l'Etat à ceux qui daignaient acheter les suffrages de la canaille qui les composait.

A l'égard des curies, l'instituteur en ayant fait dix en chaque tribu, tout le peuple romain alors renfermé dans les murs de la ville se trouva composé de trente curies, dont chacune avait ses temples, ses dieux, ses officiers, ses prêtres, et ses fêtes appelées compitalia, semblables aux paganalia qu'eurent dans la suite les tribus rustiques.

Au nouveau partage de Servius ce nombre de trente ne pouvant se répartir également dans ses quatre tribus, il n'y voulut point toucher, et les curies indépendantes des tribus devinrent une autre division des habitants de Rome. Mais il ne fut point question de curies ni dans les tribus rustiques ni dans le peuple qui les composait, parce que les tribus étant devenues un établissement purement civil, et une autre police ayant été introduite pour la levée des troupes, les divisions militaires de Romulus se trouvèrent superflues. Ainsi, quoique tout citoyen fût inscrit dans une tribu, il s'en fallait beaucoup que chacun ne le fût dans une curie.

Servius fit encore une troisième division qui n'avait aucun rapport aux deux précédentes, et devint par ses effets la plus importante de toutes. Il distribua tout le peuple romain en six classes, qu'il ne distingua ni par le lieu ni par les hommes, mais par les biens. En sorte que les premières classes étaient remplies par les riches, les dernières par les pauvres, et les moyennes par ceux qui jouissaient d'une fortune médiocre. Ces six classes étaient subdivisées en cent quatre-vingt-treize autres corps appelés centuries, et ces corps étaient tellement distribués que la première classe en comprenait seule plus de la moitié, et la dernière n'en formait qu'un seul. Il se trouva ainsi que la classe la moins nombreuse en hommes l'était le plus en centuries, et que la dernière classe entière n'était comptée que pour une subdivision, bien qu'elle contînt seule plus de la moitié des habitants de Rome.

Afin que le peuple pénétrât moins les conséquences de cette dernière forme, Servius affecta de lui donner un air militaire: il inséra dans la seconde classe deux centuries d'armuriers, et deux d'instruments de guerre dans la quatrième. Dans chaque classe, excepté la dernière, il distingua les jeunes et les vieux, c'est-à-dire ceux qui étaient obligés de porter les armes, et ceux que leur âge en exemptait par les lois; distinction qui plus que celle des biens produisit la nécessité de recommencer souvent le cens ou dénombrement. Enfin il voulut que l'assemblée se tînt au champ de Mars, et que tous ceux qui étaient en âge de servir y vinssent avec leurs armes.

La raison pour laquelle il ne suivit pas dans la dernière classe cette même division des jeunes et des vieux, c'est qu'on n'accordait point à la populace dont elle était composée l'honneur de porter les armes pour la patrie; il fallait avoir des foyers pour obtenir le droit de les défendre, et de ces innombrables troupes de gueux dont brillent aujourd'hui les armées des rois, il n'y en a pas un, peut-être, qui n'eût été chassé avec dédain d'une cohorte romaine, quand les soldats étaient les défenseurs de la liberté.

On distingua pourtant encore dans la dernière classe les prolétaires de ceux qu'on appelait capite censi Les premiers, non tout à fait réduits à rien, donnaient au moins des citoyens à l'Etat, quelquefois même des soldats dans les besoins pressants. Pour ceux qui n'avaient rien du tout et qu'on ne pouvait dénombrer que par leurs têtes, ils étaient tout à fait regardés comme nuls, et Marius fut le premier qui daigna les enrôler.

Sans décider ici si ce troisième dénombrement était bon ou mauvais en lui-même, je crois pouvoir affirmer qu'il n'y avait que les moeurs simples des premiers Romains, leur désintéressement, leur goût pour l'agriculture, leur mépris pour le commerce et pour l'ardeur du gain, qui pussent le rendre praticable. Où est le peuple moderne chez lequel la dévorante avidité, l'esprit inquiet, l'intrigue, les déplacements continuels, les perpétuelles révolutions des fortunes pussent laisser durer vingt ans un pareil établissement sans bouleverser tout l'Etat? Il faut même bien remarquer que les moeurs et la censure plus fortes que cette institution en corrigèrent le vice à Rome, et que tel riche se vit relégué dans la classe des pauvres, pour avoir trop étalé sa richesse.

De tout ceci l'on peut comprendre aisément pourquoi il n'est presque jamais fait mention que de cinq classes, quoiqu'il y en eût réellement six. La sixième, ne fournissant ni soldats à l'armée ni votants au champ de Mars (Note 40) et n'étant presque d'aucun usage dans la République, était rarement comptée pour quelque chose.

Telles furent les différentes divisions du peuple romain. Voyons à présent l'effet qu'elles produisaient dans les assemblées. Ces assemblées légitimement convoquées s'appelaient comices, elles se tenaient ordinairement dans la place de Rome au champ de Mars, et se distinguaient en comices par curies, comices par centuries, et comices par tribus, selon celle de ces trois formes sur laquelle elles étaient ordonnées: les comices par curies étaient de l'institution de Romulus, ceux par centuries de Servius, ceux par tribus des tribuns du peuple. Aucune loi ne recevait la sanction, aucun magistrat n'était élu que dans les comices, et comme il n'y avait aucun citoyen qui ne fût inscrit dans une curie, dans une centurie, ou dans une tribu, il s'ensuit qu'aucun citoyen n'était exclu du droit de suffrage, et que le peuple romain était véritablement souverain de droit et de fait.

Pour que les comices fussent légitimement assemblés et que ce qui s'y faisait eût force de loi il fallait trois conditions: la première que le corps ou le magistrat qui les convoquait fût revêtu pour cela de l'autorité nécessaire; la seconde que l'assemblée se fît un des jours permis par la loi; la troisième que les augures fussent favorables.

La raison du premier règlement n'a pas besoin d'être expliquée. Le second est une affaire de police; ainsi il n'était pas permis de tenir les comices les jours de férie et de marché, où les gens de la campagne venant à Rome pour leurs affaires n'avaient pas le temps de passer la journée dans la place publique. Par le troisième le Sénat tenait en bride un peuple fier et remuant, et tempérait à propos l'ardeur des tribuns séditieux; mais ceux-ci trouvèrent plus d'un moyen de se délivrer de cette gêne.

Les lois et l'élection des chefs n'étaient pas les seuls points soumis au jugement des comices. Le peuple romain ayant usurpé les plus importantes fonctions du gouvernement, on peut dire que le sort de l'Europe était réglé dans ses assemblées. Cette variété d'objets donnait lieu aux diverses formes que prenaient ces assemblées selon les matières sur lesquelles il avait à prononcer.

Pour juger de ces diverses formes il suffit de les comparer. Romulus en instituant les curies avait en vue de contenir le Sénat par le peuple et le peuple par le Sénat, en dominant également sur tous. Il donna donc au peuple par cette forme toute l'autorité du nombre pour balancer celle de la puissance et des richesses qu'il laissait aux patriciens. Mais selon l'esprit de la monarchie, il laissa cependant plus d'avantage aux patriciens par l'influence de leurs clients sur la pluralité des suffrages. Cette admirable institution des patrons et des clients fut un chef-d'oeuvre de politique et d'humanité, sans lequel le patriciat, si contraire à l'esprit de la République, n'eût pu subsister. Rome seule a eu l'honneur de donner au monde ce bel exemple, duquel il ne résulta jamais d'abus, et qui pourtant n'a jamais été suivi.

Cette même forme des curies ayant subsisté sous les rois jusqu'à Servius, et le règne du dernier Tarquin n'étant point compté pour légitime, cela fit distinguer généralement les lois royales par le nom de leges curiatae.

Sous la République les curies, toujours bornées aux quatre tribus urbaines, et ne contenant plus que la populace de Rome, ne pouvaient convenir ni au Sénat qui était à la tête des patriciens, ni aux tribuns qui, quoique plébéiens, étaient à la tête des citoyens aisés. Elles tombèrent donc dans le discrédit, et leur avilissement fut tel que leurs trente licteurs assemblés faisaient ce que les comices par curies auraient dû faire.

La division par centuries était si favorable à l'aristocratie qu'on ne voit pas d'abord comment le Sénat ne l'emportait pas toujours dans les comices qui portaient ce nom, et par lesquels étaient élus les consuls, les censeurs, et les autres magistrats curules. En effet des cent quatre-vingt-treize centuries qui formaient les six classes de tout le peuple romain, la première classe en comprenant quatre-vingt-dix-huit, et les voix ne se comptant que par centuries, cette seule première classe l'emportait en nombre de voix sur toutes les autres. Quand toutes ses centuries étalent d'accord on ne continuait pas même à recueillir les suffrages; ce qu'avait décidé le plus petit nombre passait pour une décision de la multitude, et l'on peut dire que dans les comices par centuries les affaires se réglaient à la pluralité des écus bien plus qu'à celle des voix.

Mais cette extrême autorité se tempérait par deux moyens. Premièrement les tribuns pour l'ordinaire, et toujours un grand nombre de plébéiens, étant dans la classe des riches balançaient le crédit des patriciens dans cette première classe.

Le second moyen consistait en ceci, qu'au lieu de faire d'abord voter les centuries selon leur ordre, ce qui aurait toujours fait commencer par la première, on en tirait une au sort, et celle-là (Note 41) procédait seule à l'élection; après quoi toutes les centuries appelées un autre jour selon leur rang répétaient la même élection et la confirmaient ordinairement. On ôtait ainsi l'autorité de l'exemple au rang pour la donner au sort selon le principe de la démocratie.

Il résultait de cet usage un autre avantage encore; c'est que les citoyens de la campagne avaient le temps entre les deux élections de s'informer du mérite du candidat provisionnellement nommé, afin de ne donner leur voix qu'avec connaissance de cause. Mais sous prétexte de célérité l'on vint à bout d'abolir cet usage, et les deux élections se firent le même jour.

Les comices par tribus étaient proprement le conseil du peuple romain. Ils ne se convoquaient que par les tribuns; les tribuns y étaient élus et y passaient leurs plébiscites. Non seulement le Sénat n'y avait point de rang, il n'avait pas même le droit d'y assister, et forcés d'obéir à des lois sur lesquelles ils n'avaient pu voter, les sénateurs à cet égard étaient moins libres que les derniers citoyens. Cette injustice était tout à fait mal entendue, et suffisait seule pour invalider les décrets d'un corps où tous ses membres n'étaient pas admis. Quand tous les patriciens eussent assisté à ces comices selon le droit qu'ils en avaient comme citoyens, devenus alors simples particuliers ils n'eussent guère influé sur une forme de suffrages qui se recueillaient par tête, et où le moindre prolétaire pouvait autant que le prince du Sénat.

On voit donc qu'outre l'ordre qui résultait de ces diverses distributions pour le recueillement des suffrages d'un si grand peuple, ces distributions ne se réduisaient pas à des formes indifférentes en elles-mêmes, mais que chacune avait des effets relatifs aux vues qui la faisaient préférer.

Sans entrer là-dessus en de plus longs détails, il résulte des éclaircissements précédents que les comices par tribus étaient les plus favorables au gouvernement populaire, et les comices par centuries à l'aristocratie. A l'égard des comices par curies où la seule populace de Rome formait la pluralité, comme ils n'étaient bons qu'à favoriser la tyrannie et les mauvais desseins, ils durent tomber dans le décri, les séditieux eux-mêmes s'abstenant d'un moyen qui mettait trop à découvert leurs projets. Il est certain que toute la majesté du peuple romain ne se trouvait que dans les comices par centuries, qui seuls étaient complets; attendu que dans les comices par curies manquaient les tribus rustiques, et dans les comices par tribus le Sénat et les patriciens.

Quant à la manière de recueillir les suffrages, elle était chez les premiers Romains aussi simple que leurs moeurs, quoique moins simple encore qu'à Sparte. Chacun donnait son suffrage à haute voix, un greffier les écrivait à mesure; pluralité de voix dans chaque tribu déterminait le suffrage de la tribu, pluralité de voix entre les tribus déterminait le suffrage du peuple, et ainsi des curies et des centuries. Cet usage était bon tant que l'honnêteté régnait entre les citoyens et que chacun avait honte de donner publiquement son suffrage à un avis injuste ou à un sujet indigne; mais quand le peuple se corrompit et qu'on acheta les voix, il convint qu'elles se donnassent en secret pour contenir les acheteurs par la défiance, et fournir aux fripons le moyen de n'être pas des traîtres.

Je sais que Cicéron blâme ce changement et lui attribue en partie la ruine de la République. Mais quoique je sente le poids que doit avoir ici l'autorité de Cicéron, je ne puis être de son avis. Je pense, au contraire, que pour n'avoir pas fait assez de changements semblables on accéléra la perte de l'Etat. Comme le régime des gens sains n'est pas propre aux malades, il ne faut pas vouloir gouverner un peuple corrompu par les mêmes lois qui conviennent à un bon peuple. Rien ne prouve mieux cette maxime que la durée de la République de Venise, dont le simulacre existe encore, uniquement parce que ses lois ne conviennent qu'à de méchants hommes.

On distribua donc aux citoyens des tablettes par lesquelles chacun pouvait voter sans qu'on sût quel était son avis. On établit aussi de nouvelles formalités pour le recueillement des tablettes, le compte des voix, la comparaison des nombres, etc. Ce qui n'empêcha pas que la fidélité des officiers chargés de ces fonctions (Note 42) ne fût souvent suspectée. On fit enfin, pour empêcher la brigue et le trafic des suffrages, des édits dont la multitude montre l'inutilité.

Vers les derniers temps, on était souvent contraint de recourir à des expédients extraordinaires pour suppléer à l'insuffisance des lois. Tantôt on supposait des prodiges; mais ce moyen qui pouvait en imposer au peuple n'en imposait pas à ceux qui le gouvernaient; tantôt on convoquait brusquement une assemblée avant que les candidats eussent eu le temps de faire leurs brigues; tantôt on consumait toute une séance à parler quand on voyait le peuple gagné prêt à prendre un mauvais parti. Mais enfin l'ambition éluda tout; et ce qu'il y a d'incroyable, c'est qu'au milieu de tant d'abus ce peuple immense, à la faveur de ses anciens règlements, ne laissait pas d'élire les magistrats, de passer les lois, de juger les causes, d'expédier les affaires particulières et publiques, presque avec autant de facilité qu'eût pu faire le Sénat lui-même.

CHAPTER V

THE TRIBUNATEWHEN an exact proportion cannot be established between the constituent parts of the State, or when causes that cannot be removed continually alter the relation of one part to another, recourse is had to the institution of a peculiar magistracy that enters into no corporate unity with the rest. This restores to each term its right relation to the others, and provides a link or middle term between either prince and people, or prince and Sovereign, or, if necessary, both at once.

This body, which I shall call the tribunate, is the preserver of the laws and of the legislative power. It serves sometimes to protect the Sovereign against the government, as the tribunes of the people did at Rome; sometimes to uphold the government against the people, as the Council of Ten now does at Venice; and sometimes to maintain the balance between the two, as the Ephors did at Sparta.

The tribunate is not a constituent part of the city, and should have no share in either legislative or executive power; but this very fact makes its own power the greater: for, while it can do nothing, it can prevent anything from being done. It is more sacred and more revered, as the defender of the laws, than the prince who executes them, or than the Sovereign which ordains them. This was seen very clearly at Rome, when the proud patricians, for all their scorn of the people, were forced to bow before one of its officers, who had neither auspices nor jurisdiction.

The tribunate, wisely tempered, is the strongest support a good constitution can have; but if its strength is ever so little excessive, it upsets the whole State. Weakness, on the other hand, is not natural to it: provided it is something, it is never less than it should be.

It degenerates into tyranny when it usurps the executive power, which it should confine itself to restraining, and when it tries to dispense with the laws, which it should confine itself to protecting. The immense power of the Ephors, harmless as long as Sparta preserved its morality, hastened corruption when once it had begun. The blood of Agis, slaughtered by these tyrants, was avenged by his successor; the crime and the punishment of the Ephors alike hastened the destruction of the republic, and after Cleomenes Sparta ceased to be of any account. Rome perished in the same way: the excessive power of the tribunes, which they had usurped by degrees, finally served, with the help of laws made to secure liberty, as a safeguard for the emperors who destroyed it. As for the Venetian Council of Ten, it is a tribunal of blood, an object of horror to patricians and people alike; and, so far from giving a lofty protection to the laws, it does nothing, now they have become degraded, but strike in the darkness blows of which no one dare take note.

The tribunate, like the government, grows weak as the number of its members increases. When the tribunes of the Roman people, who first numbered only two, and then five, wished to double that number, the senate let them do so, in the confidence that it could use one to check another, as indeed it afterwards freely did.

The best method of preventing usurpations by so formidable a body, though no government has yet made use of it, would be not to make it permanent, but to regulate the periods during which it should remain in abeyance. These intervals, which should not be long enough to give abuses time to grow strong, may be so fixed by law that they can easily be shortened at need by extraordinary commissions.

This method seems to me to have no disadvantages, because, as I have said, the tribunate, which forms no part of the constitution, can be removed without the constitution being affected. It seems to be also efficacious, because a newly restored magistrate starts not with the power his predecessor exercised, but with that which the law allows him.

CHAPITRE V

DU TRIBUNATQuand on ne peut établir une exacte proportion entre les parties constitutives de l'Etat, ou que des causes indestructibles en altèrent sans cesse les rapports, alors on institue une magistrature particulière qui ne fait point corps avec les autres, qui replace chaque terme dans son vrai rapport, et qui fait une liaison ou un moyen terme soit entre le prince et le peuple, soit entre le prince et le souverain, soit à la fois des deux côtés s'il est nécessaire.

Ce corps, que j'appellerai tribunat, est le conservateur des lois et du pouvoir législatif. Il sert quelquefois à protéger le souverain contre le gouvernement, comme faisaient à Rome les tribuns du peuple, quelquefois à soutenir le gouvernement contre le peuple, comme fait maintenant à Venise le conseil des Dix, et quelquefois à maintenir l'équilibre de part et d'autre, comme faisaient les éphores à Sparte.

Le tribunat n'est point une partie constitutive de la cité, et ne doit avoir aucune portion de la puissance législative ni de l'exécutive, mais c'est en cela même que la sienne est plus grande: car ne pouvant rien faire il peut tout empêcher. Il est plus sacré et plus révéré comme défenseur des lois que le prince qui les exécute et que le souverain qui les donne. C'est ce qu'on vit bien clairement à Rome quand ces fiers patriciens, qui méprisèrent toujours le peuple entier, furent forcés de fléchir devant un simple officier du peuple, qui n'avait ni auspices ni juridiction.

Le tribunat sagement tempéré est le plus ferme appui d'une bonne constitution; mais pour peu de force qu'il ait de trop il renverse tout. A l'égard de la faiblesse, elle n'est pas dans sa nature, et pourvu qu'il soit quelque chose, il n'est jamais moins qu'il ne faut.

Il dégénère en tyrannie quand il usurpe la puissance exécutive dont il n'est que le modérateur, et qu'il veut dispenser les lois qu'il ne doit que protéger. L'énorme pouvoir des éphores, qui fut sans danger tant que Sparte conserva ses moeurs, en accéléra la corruption commencée. Le sang d'Agis égorgé par ces tyrans fut vengé par son successeur: le crime et le châtiment des éphores hâtèrent également la perte de la République, et après Cléomène Sparte ne fut plus rien. Rome périt encore par la même voie, et le pouvoir excessif des tribuns usurpé par degrés servit enfin, à l'aide des lois faites pour la liberté, de sauvegarde aux empereurs qui la détruisirent. Quant au conseil des Dix à Venise, c'est un tribunal de sang, horrible également aux patriciens et au peuple, et qui, loin de protéger hautement les lois, ne sert plus, après leur avilissement, qu'à porter dans les ténèbres des coups qu'on n'ose apercevoir.

Le tribunat s'affaiblit comme le gouvernement par la multiplication de ses membres. Quand les tribuns du peuple romain, d'abord au nombre de deux, puis de cinq, voulurent doubler ce nombre, le Sénat les laissa faire, bien sûr de contenir les uns par les autres; ce qui ne manqua pas d'arriver.

Le meilleur moyen de prévenir les usurpations d'un si redoutable corps, moyen dont nul gouvernement ne s'est avisé jusqu'ici, serait de ne pas rendre ce corps permanent, mais de régler des intervalles durant lesquels il resterait supprimé. Ces intervalles, qui ne doivent pas être assez grands pour laisser aux abus le temps de s'affermir, peuvent être fixés par la loi, de manière qu'il soit aisé de les abréger au besoin par des commissions extraordinaires.

Ce moyen me paraît sans inconvénient, parce que, comme je l'ai dit, le tribunat ne faisant point partie de la constitution peut être ôté sans qu'elle en souffre; et il me paraît efficace, parce qu'un magistrat nouvellement rétabli ne part point du pouvoir qu'avait son prédécesseur, mais de celui que la loi lui donne

CHAPTER VI

THE DICTATORSHIPTHE inflexibility of the laws, which prevents them from adapting themselves to circumstances, may, in certain cases, render them disastrous, and make them bring about, at a time of crisis, the ruin of the State. The order and slowness of the forms they enjoin require a space of time which circumstances sometimes withhold. A thousand cases against which the legislator has made no provision may present themselves, and it is a highly necessary part of foresight to be conscious that everything cannot be foreseen.

It is wrong therefore to wish to make political institutions so strong as to render it impossible to suspend their operation. Even Sparta allowed its laws to lapse.

However, none but the greatest dangers can counterbalance that of changing the public order, and the sacred power of the laws should never be arrested save when the existence of the country is at stake. In these rare and obvious cases, provision is made for the public security by a particular act entrusting it to him who is most worthy. This commitment may be carried out in either of two ways, according to the nature of the danger.

If increasing the activity of the government is a sufficient remedy, power is concentrated in the hands of one or two of its members: in this case the change is not in the authority of the laws, but only in the form of administering them. If, on the other hand, the peril is of such a kind that the paraphernalia of the laws are an obstacle to their preservation, the method is to nominate a supreme ruler, who shall silence all the laws and suspend for a moment the sovereign authority. In such a case, there is no doubt about the general will, and it is clear that the people's first intention is that the State shall not perish. Thus the suspension of the legislative authority is in no sense its abolition; the magistrate who silences it cannot make it speak; he dominates it, but cannot represent it. He can do anything, except make laws.

The first method was used by the Roman senate when, in a consecrated formula, it charged the consuls to provide for the safety of the Republic. The second was employed when one of the two consuls nominated a dictator:38 a custom Rome borrowed from Alba.