Gaius

Julius Caesar Gaius

Julius Caesar

ca. 100-44 BC.

Julius

Caesar's War Commentaries: Julius

Caesar's War Commentaries:

Caesar Augustus

(Gaius Octavius) (31 BC - 14 AD) Caesar Augustus

(Gaius Octavius) (31 BC - 14 AD)

63 BC - 14 AD. Emperor, 27 BC

- 14 AD.

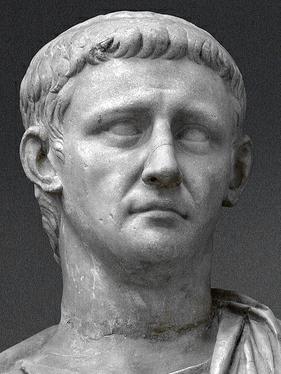

Tiberius

(14-37 AD) Tiberius

(14-37 AD)

Augustus

brought his step-son Tiberius to co-rule with him in his later days,

giving indication of his desires for a successor. The 23 years of

sole rule by Tiberius after his father's death marked a continuation of

Augustus' policies. Tiberius also possessed much of the

diplomatic skill and energy of Augustus – and was undoubtedly the best

of the Julio-Claudian successors.

The reign of Tiberius

was generally a peaceful time for Rome – though turbulent within the

higher reaches of Roman politics as Tiberius gradually descended into a

highly paranoid condition, executing many around him that he suspected

of personal disloyalty (including many of his personal

relatives). This grim situation continued all the way to his

death in 37 AD.

Caligula

(Gaius) (37-41 AD) Caligula

(Gaius) (37-41 AD)

Tiberius was succeeded by his grandnephew Gaius or "Caligula" (little boots) who was probably insane. Ultimately, he was a wastrel ruled by his grand lusts--which

over time turned into true insanity. His rule was thus not much less violent and he and his family were assassinated after only four years of his rule.

Claudius (41-54

AD) Claudius (41-54

AD)

Caligula's

uncle (and Tiberius's nephew) Claudius replaced him – just as the

Senate was giving thought to restoring the Republic. The army's

Praetorian Guard stepped in and declared Claudius emperor – putting an

end to the question. (This would mark the beginning of the role

of the Praetorian Guard as emperor-makers – as well as emperor

"unmakers" or assassins, according to their own political

preferences). Claudius probably survived the purges of his

relatives Tiberius and Caligula – mostly because he was considered to

be an unlikely threat to these men, perhaps because of some kind of

disability.

He basically continued

to move the Empire toward the vision that had once directed the actions

of Augustus. He strengthened the Imperial bureaucracy. He completed

the incorporation of client-states into the direct rule of the empire.

He succeeded in bringing southern Britain under Roman rule. But he

lacked polish and was the object of ridicule for his personal ways.

But he too also developed violent suspicions of those around him, in

particular a number of Senators. In 54 AD he was probably

poisoned – possibly by his wife (who was certainly afraid that he was

going to pass over her son Nero in favor of another imperial candidate).

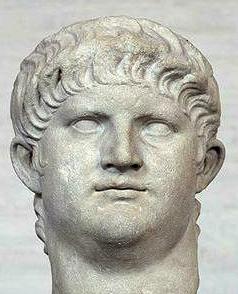

Nero

(54-68 AD) Nero

(54-68 AD)

Thus

Nero, with the help of his conniving mother (whom he will execute in 59

AD) became emperor at age 16. He started off his reign fairly

popular with the people – whom he was always trying to please. He did

what he could to beautify Rome, building theaters and sponsoring

gladiatorial contests to amuse the people. However his projects

grew increasingly extravagant and became a serious burden on the

finances of the Empire. Also, arrogant and by nature suspicious,

Nero became increasingly paranoid and ruthless (even murderous) to a

large circle of individuals immediately around him, including his old

tutor, Seneca.

The Burning of Rome.

In 64 much of Rome burned (actually not an entirely uncommon

occurrence). Rumors were that he himself had done this in an

effort to clear the Roman slums to make way for his expensive,

ever-expanding urban beautification projects. According to the

historian Tacitus, Nero attempted to deflect the blame for the fire on

to the Christians (who were growing rapidly in number in Rome – and

also gaining in a bad reputation for their un-Roman "secret'

ways). He attempted to validate his own accusations against the

Christians by offering the Roman public the entertaining spectacle of

horrible deaths inflicted on members of this "vile sect."

The subduing of Britain.

During his reign he encountered – and largely overcame – rebellions in

various parts of the Empire, most notably in Britain (Queen Boudica's

Revolt of 60-61). Beginning in AD 43, under the Emperor Claudius,

the Romans had begun the process of subduing Britain, one region at a

time. By 47 Britain south of the Humber River and east of Wales

was under Roman control. By AD 60 (Nero was ruling Rome by this

time) the Roman legions had destroyed the Druid religious or political

center at Mona (or Anglesey). But the following year, 61, a major

Celtic uprising led by the Celtic Queen Boudica threatened to reverse

these Roman victories. Emperor Nero was even considering

abandoning Britain when Roman legions under Suetonius defeated a huge

Celtic army – possibly 10 times the size of the Roman army – somewhere

along the main Roman road (later, in the Middle Ages, termed "Watling

Street") which ran from the English Channel to Wales.

The first Jewish-Roman war AD 67-70.

He actually demonstrated diplomatic talent in the way he resolved a

dispute with Parthia (the former Persia) over the kingdom of Armenia

(AD 63) and in securing a peace between these two empires that would

last 50 years.

But eventually revolt also touched the heart of Rome itself: Nero found

himself facing down rebellion and conspiracy – from many different

directions. Even the army was growing unreliable in its support

of its emperor. Finally hearing of a major rebellion brewing, and

finding that no one supported him any longer, he took his own life (AD

68). He was only 30 years old at his death. And with his death

the Julio-Claudian line came to an end.

A Period of Confusion

(68-70 AD)

When Nero died there was a rather thorough

murder of the last of the successors to the Julio-Claudian line of emperors.

This in turn produced a civil war which was decided not by Roman political

leadership but by the might of the contending Roman armies. After

a two-year struggle among a number of major contenders, Vespasian emerged

as the remaining candidate for the imperial title.

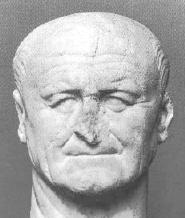

Vespasian

(70-79 AD) Vespasian

(70-79 AD)

Lacking any special family ties or

noble line Vespasian attempted to undergird his hold over the principate

by assuming for himself the title of Caesar. Thus the term

Caesar

now referred not to the Italian family that had once ruled the Roman principate--but

was transformed during Vespasian's rule into a political title or office.

Caesar

now was a title of special imperial authority.

His rule was further undergirded

by strengthening the move started under Augustus to recommend to the Romans

(especially those with Eastern roots where emperor-worship had a natural

history) special reverence for the imperial caesar--to view the

princeps as a ruler with special sacred authority within the empire.

The last year of his rule marked

the beginning of the conquest of northern Britain (under General Agricola):

78-84.

Titus (79-81) Titus (79-81)

Vespasian's

eldest son Titus succeeded his father as emperor. He had

distinguished himself under his father's rule as the commander of the

eastern legions that forced Judea back into submission. As

emperor his rule was short – and troubled. Pompeii was destroyed

by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 and in 80 much of Rome was

destroyed by fire. Otherwise he too was proving to be an

excellent administrator. But Titus died in 81 – seemingly of

natural causes.

Domitian (81-96

AD)

Titus's

place was immediately taken by his brother Domitian ... thanks to the

support of the Praetorian Guard. Domitian was more arrogant –

assuming tremendous powers as the society's divinely ordained

enlightened despot in his effort to rebuild the imperial character of

Rome ... including the physical rebuilding of the city itself, which

had suffered tremendous damage from the recent fires and civil war.

No effort was made to continue the pretense of the Republic's

existence. He ignored the Senate (which grew to hate him) and

surprisingly gave no special favors to his family, very unusual in

imperial politics. He presided over a tightly organized and

surprisingly uncorrupt bureaucracy. He spent most of his time

away from the capital city, leading battles or conducting inspection

tours ... and thus the seat of his government tended to be wherever he

himself was located. It was during his emperorship that Celtic

Britain was finally defeated (by General Agricola) and brought into the

Roman Empire ... except for the northern portions (Scotland) whose

troops managed to escape the grip of the Roman legions.

He cultivated the support of the crowds – with lavish gladiatorial

games in the new Coliseum and through distributions of monies to the

residents of Rome. Surprisingly his regime ended with money still

in the state treasury, probably because of all the wealth he

accumulated by seizing the property of people he had begun to

fear. In 96 he was assassinated in a plot directed by his

own court officials. But in any case, this brought the Flavian

line to an end.

Nerva (96-98)

Nerva

was raised in political, not military circles, and his accession to

power was via the Senate, where he was popular. He immediately

freed the people that Domitian had imprisoned and restored to them

their property he had confiscated. He also attempted to cultivate

popular support in Rome through the lowering of taxes and extensive

welfare grants to the poor. But this created financial problems

for the government. Also Domitian had been popular with the Roman

army. In fact, the Praetorian Guard seized Nerva and forced him

to turn over to them the individuals involved in the death plot against

Domitian. Nerva's rule was brief – he was probably chosen by the

Senate because he was old and childless – and he died of a stroke after

only two years of rule.

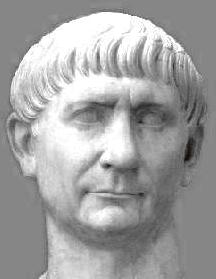

Trajan

(98-117) Trajan

(98-117)

Under

the insistence of the Praetorian Guard, Nerva had named the prominent

general Trajan as his "adopted son (successor). As emperor he

proved to be a capable administrator, as well as a promoter of further

military successes for Rome. He built in Rome both a new forum

and market as well as some important ceremonial landmarks (Trajan's

column). But it is in the area of military and diplomatic policy

that he is best remembered. Under his rule the Empire reached its

furthest extent.

In 106 Trajan forcibly incorporated into the Empire the kingdom of

Dacia (roughly present-day Romania) and the Nabataean kingdom

(present-day Jordan and northwestern Saudi Arabia). In 113 he

turned on Parthia (in present day Iran and Iraq). The Parthian

king Osroes had forced on Armenia a king of Osroes's choosing – in

violation of the Roman-Parthian treaty secured by Nero which had made

Armenia (in the land between the Black Sea and the lower Caspian Sea) a

joint protectorate of both these two great empires. Thus Trajan marched

into Armenia and placed his own man on the Armenian throne. Then

in 116 Trajan continued his conquest into Parthia itself, seizing

Babylon, Ctesiphon, and Susa, deposing Osroes, and placing his own

ruler on the Parthian throne.

But the venture overtaxed his energies – and he faced rebellion in many

places in the newly expanded Empire. Mesopotamia was restless,

and once again the Jews rose up in rebellion against Rome. Very ill, he

managed to return to Rome before he died there in 117. The Romans

knew that they had lost a great Emperor – one of their very best.

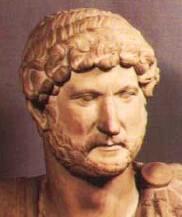

Hadrian

(117-138)

HA

distant relative of the childless Trajan, and supported by Trajan's

wife Plotina, Hadrian was named as successor as Trajan lay dying.

The Senate quickly endorsed the choice. Hadrian had served with

Trajan as something of a military administrator during Trajan's

military campaigns – and was in fact left by Trajan as Governor of

Syria in order to pacify the rebellious Jews.

Hadrian sought to be an excellent administrator and diplomat rather

than conqueror. He chose to spend more than half of his time as

Emperor outside Italy, conducting important inspection tours of the

various provinces of the Empire – enabled largely because his political

position in Rome with the Senators was so secure. Upon accession

to the imperial throne he quickly surmised that holding Mesopotamia

would prove to be more taxing on Roman strength than it would be worth

– and acknowledged Parthia's claim to that region. But elsewhere

Hadrian was determined to hold the line of defense against Rome's

tribal enemies – erecting walls and fortresses in protection of Rome's

now rather "fixed" borders in northern Britain, along the Rhine, along

the Danube, and between these two rivers (the Rhine-Danube limes).

He saw himself as something of an intellectual as well. He

greatly admired Greek philosophy and literature (he even started the

fashion of wearing a beard, Greek-style) and considered himself a poet

and Stoic and Epicurean philosopher.

The end of his rule was marked by a major crisis in Judea – where he

faced massive and destructive revolt by the Jews, led by Bar

Kokhba. The problem began when he rebuilt Jerusalem (destroyed in

the earlier 67-70 Jewish rebellion) – but as a Roman city, Aelia

Capitolina. He also erected a temple to Jupiter on the

foundations of the leveled Jewish Temple. And he decreed an end

to the "barbaric" Jewish practice of circumcision. This proved to

be too much to the Jews and in 132 they rose up again in rebellion. The

Jews proved to be very difficult to tame: he possibly lost an entire

legion to the Jews, and had to call in legions from all around the

Empire to finally bring the Jews to submission in 135. The loss

of Jewish life and social position was enormous. A vindictive

Hadrian dedicated himself to rooting out Judaism from the Empire.

His health was failing and he twice named a successor (the first one

died ahead of him) as he saw his end coming nearer. His choice

was disputed by relatives who attempted a coup – and whom he put to

death. But in 138 his death finally arrived.

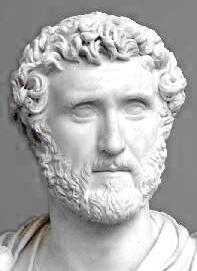

Antoninus Pius

(138-161)

Antoninus was given

the title "Pius" (pious) for his devotion (piety) to his benefactor

Hadrian, whom he pressured the Senate to deify after Hadrian's

death. Importantly also, his devotion was demonstrated in his

willingness to honor Hadrian's deathbed request to Antoninus to adopt

as his own sons two individuals – who would later become the emperors

Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Antoninus did not come to prominence as a military man – nor did he

ever develop any relationship with any of the legions as had those

before and after him. His rule was the most peaceful of any in

the long run of the Empire – though he had to deal with relatively

small military disturbances from time to time. He never left

Italy to personally face disturbances, but always worked through Rome's

governors – drawing praise from many for his relatively peaceful

handling of Roman politics. However this seemed to have produced

the impression of Roman weakness in the estimation of many of Rome's

enemies (such as the ever troublesome Parthians) – which his successors

would have to deal with.

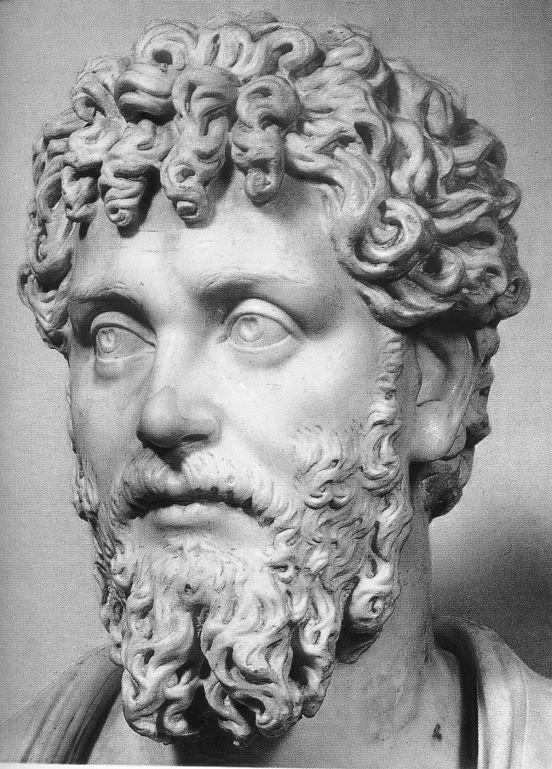

Marcus

Aurelius (161-180) Marcus

Aurelius (161-180)

Marcus

had the very best education of the time and demonstrated a keen

intellect very early in life. He had a natural affinity for

philosophy – which would reveal itself later when he became

Emperor. Upon his accession he insisted his younger adoptive

brother Verus serve as co-emperor – as a way of keeping the immense

army under imperial command, rather than the command of the generals –

while Rome fought off Germans and Parthians simultaneously on two

widely separated fronts.

The German tribes had

taken advantage of Antoninus's softness and were regularly crossing the

Roman border along the Rhine and Danube Rivers (pressure from tribal

peoples further east was also part of the reason). In 166 this

situation became very serious when the Persian Sarmatians raided the

borderlands of the eastern Danube and the Marcomanni, Lombards and

other German tribes crossed the Danube in huge numbers. Both Marcus and

Verus led the counterattack of the Roman Legions. But they were

unable to subdue their tribal enemies. Then when in 169 Varus

died, Marcus was left alone to deal with the situation – which merely

grew worse. The Marcomanni seemed unstoppable in their forays

into northern Italy, while other tribes were invading Macedonia and

Greece. Eventually Marcus got the Germans settled down – but by

accepting them as frontier settlers along the Danube all along the way

up to Bohemia (today's Hungary and Czech Republic).

In the meanwhile, the

Parthians had been undergoing a military revival and in 161 assaulted –

and defeated – Roman legions in Armenia and Syria. Varus was sent

out to deal with the Parthian problem ... and by 166 Varus – or

actually his general Gaius Cassius – captured the Parthian capital,

Ctesiphon, and subdued the Parthians. In 172 a revolt broke out

in Egypt – and again Cassius came to the rescue.

When in 175 a rumor

broke out that Marcus Aurelius had died, Cassius moved to have himself

declared Emperor by his political and military supporters in the East

(principally Syria, Palestine, and Egypt). Although the

misunderstanding was quickly cleared up, the Empire found itself caught

in a civil war. But Cassius's extensive support in Rome's eastern

provinces could not measure up to Marcus's overall support – and the

rebellion ended when one of Cassius's own centurions murdered

him. Ever the Stoic, Marcus was actually saddened by the whole

misadventure.

As ruler of a mighty

empire, there was something Solomon-like about Marcus Aurelius.

From 170 until his death in 180, he recorded his thoughts (in Greek) on

life, death, virtue, human purpose, etc. – that had all the qualities

of Solomon's philosophical reflections found in Ecclesiastes in the

Hebrew Bible (or even of Buddha's teachings about the folly of human

desire). His writings were later collected into a single work,

Meditations. It is a classic in Stoic thought.

In 178 he was forced

to turn his attentions back to the Germans along the Danube. He

again defeated the Germans soundly. The possibility of annexing

Bohemia to the Empire now presented itself. But Marcus's health was

failing him and the idea had to be abandoned. He died in 180 at

Vindobona (Vienna) along the German border.

Marcus

Aurelius' major works or writings:

Meditations

(167 AD) Marcus

Aurelius' major works or writings:

Meditations

(167 AD)

Commodus

(180-192) Commodus

(180-192)

Commodus,

Marcus Aurelius' son, brings the period of the "Five Good Emperors' to

an end. His rule marks the transition to very troubled times for

the Roman Empire. From 177 (at age 15) Commodus had been

co-emperor with his father – and it was hoped that with his father's

death he would be able to continue the good government of his

father. It was not to be. Although his rule began well, a

conspiracy in 182 (promoted primarily by members of his own family) to

assassinate him turned him paranoid. And from paranoia he slipped

into insanity.

Commodus was never really interested in administering the Empire – and

left the task to personal favorites, while he indulged himself in

sports at the family estates outside Rome. In Rome itself

political infighting increased within the upper ranks of Roman politics

– which made the direction of the Empire increasingly chaotic and at

times bloody. More intrigue drove Commodus deeper into isolation

at his family estates. Meanwhile corruption was overtaking the

governance of Rome. Commodus at the same time was becoming more

murderous in his dealings with those maneuvering to take up the reins

of government he himself had dropped.

Commodus was falling increasingly into insanity. He loved to

project himself as Hercules, a god of great physical strength. He

renamed Rome after himself, termed all Romans as "Commodians,"

redrafted the months of the calendar in using his own twelve names for

the months of the year. He did this less out of guile than out of

a case of increasing simple-mindedness. But it was his behavior

in the public arena that finally braced the Senate sufficiently to

organize his death (he would entertain Roman crowds with his slaughter

of hundreds of animals and hundreds of disabled Romans – and hold

hundreds of bloodless gladiatorial combats, which he always "won,' of

course). Finally in 192 he was strangled in his bath by a

wrestler that the Senate had paid to do the job.

Unlike his five predecessors, Commodus had made no arrangements for a

smooth succession upon his death. Roman politics fell into

further chaos. Over the next year there were five different

generals who laid claim to the title of Emperor. Assassinations

and bribes followed in rapid succession as claimants attempted to line

up soldiers and Senators behind their claim to the throne.

Another Period

of Confusion (192-193)

Pertinax (192-193) was chosen emperor

but was murdered soon thereafter by the Praetorian guard. They in

turn offered the imperial position to Didius Julian (133-193). But

he was overthrown and executed by Septimus Severus when the soldiers of

the latter marched on Rome and proclaimed him emperor in 193.

Septimus

Severus (193-211) Septimus

Severus (193-211)

146-211. Begins the period of

rule by soldier-emperors--in which the imperial title is determined by

a power struggle among Roman generals and their armies. He was the

most able of the lot. He did not seek confirmation of his rule from

the Senate--and in fact ignored that body during his tenure. The

Roman army was devoted entirely to himself and his family. But constantly

challenged by contenders, draining off Roman energies in power struggles

for the imperial position.

He was a Roman general from Africa, serving at the time in Pannonia

(modern Hungary and Serbia) and was declared emperor in 193 by his

troops. He marched on Rome and seized and murdered one of the

remaining claimants, then the following year (194) defeated in battle

in Asia Minor another of the contenders. Finally in 197 Septimius

Severus defeated the last of the remaining competitors in Gaul.

He was a military dictator who replaced the untrustworthy Praetorian

Guard with Rome-based soldiers loyal to himself personally – and

executed a scores of Senators and replaced them also with

supporters. Then he went after Parthia in 197, sacking the

capital, Ctesiphon, and restored northern Mesopotamia to the Roman

Empire. He expanded the army in size nearly doubled the wages of

the soldiers – thus securing his popularity among and power over the

military. This all was made possible by increasing the taxes on

the citizenry. But his attack on the political and economic

corruption that had developed under Commodus, an action that was a very

popular with the general citizenry, helped offset the burden of

increased taxes.

Despite his own bold personality, Severus allowed himself to come under

the influence of a series of very powerful prefects of the Praetorian

Guard, in particular his cousin and friend Plautianus who almost ran

the empire for Severus. Eventually Plautianus overreached himself

and he was put to death (205). But the next two prefects proved

to be even more powerful (though better behaved!) than Plautianus.

Severus ended his days personally directing military operations against

Rome's tribal enemies who were constantly threatening Rome's

borderlands. 208 he traveled to Britain in order to extend Roman

rule even to northern Scotland. In the process his troops

slaughtered countless Scottish Celts .... but he also lost 50,000 of

his own men. In late 210 he became ill while still in Britain

... and died early the following year.

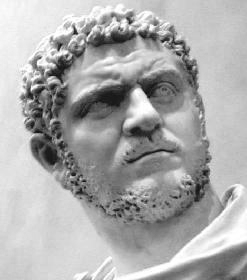

Caracalla (Antoninus)

(211-217) Caracalla (Antoninus)

(211-217)

Both

of Severus's sons succeeded him to the throne upon his death. But

Caracalla (actually a nickname derived from the Gallic hood he

typically wore) had his brother and brother's family murdered in order

to secure sole right to the imperial throne. Caracalla took great

insult to a satire produced in Alexandria (Egypt) mocking his claim

that he had acted in self-defense – and turned his soldiers over to

looting and slaughter of the city in 215, resulting in the death of

over 20,000 Alexandrians, thus establishing his reputation as one of

the cruelest of the emperors.

He treated his army lavishly – understanding the importance of keeping

happy this institution which he both admired and feared deeply.

He also created the last of the great architectural wonders of Rome: a

giant bath that could accommodate over 2,000 at a time (named,

appropriately, the Baths of Caracalla).

He was busied during much of his reign defending Rome's borders against

the Germanic Alamanni at the Rhine frontier. He was, in fact, on

his way to renew the war with Parthia in 217 when he was assassinated

by a member of the Praetorian Guard.

Macrinus (217-218)

Acting immediately,

the Prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Macrinus, claimed the title of

emperor. The Senate confirmed the decision – even though he was

the first emperor not to belong to Rome's senatorial class (he was in

fact a North African Berber of middle-class origins – though a

well-educated and highly skilled lawyer and civil bureaucrat).

He was no soldier – and was unable to command the affections of the

Roman army, a serious shortcoming as the empire became increasingly

soldier-based. Failure to deliver a victory over the Parthians in

Mesopotamia (in fact he had to secure peace by paying the Parthians 200

million sesterces in tribute) alienated the army further. Finally

a plot hatched by the Severan women to set up one of their sons,

Elagabalus, in his place – and confirmed by the army who declared

Elagabalus emperor in 218 – forced Macrinus to flee. He was soon

caught and executed.

Elagabalus (or

Heliogabalus) (218-222) Elagabalus (or

Heliogabalus) (218-222)

Elagabalus,

a Syrian named after the sun-god (El-Gabal or Heliogabalus) for which

he briefly served as priest, was only 14 when he ascended the throne.

He brought his Eastern ways with him to Rome – including the

requirement that all Romans worship Heliogabalus (also known as the Sol

Invictus or the "Unconquerable Sun') in place of Jupiter, the

traditional head of the Roman pantheon. Elagabalus then served as

a high priest as well as emperor in the process. The Romans were

not at all ready for such religious innovation. His behavior was

also even more scandalous than usual for Roman emperors (his crude

sexual adventures with both sexes and his marriage and divorce of five

women in rapid succession – including among them a Vestal Virgin – were

unpardonable sins in Roman eyes). Finally he and his mother were

assassinated by the Praetorian Guard – and his cousin was brought to

the throne.

Alexander

Severus (222-235) Alexander

Severus (222-235)

Alexander

too was only 14 when he ascended the throne. In fact it was his

mother, Julia Mamaea, who was the real power behind the throne.

In general his reign was a stable one for Rome. He did what he

could to put Rome back on something of a moral-legal basis, he

attempted to place Rome's governmental structures on a more rational

footing, and he strengthened the economy by cutting back on

governmental extravagance, lowering taxes, improving the quality of

Roman coinage, placing controls on interest rates, etc.

His difficulties developed in the area of relations with the Roman

military. He never really had control over his armies – and

mutinies were frequent. But his troubles with the military came

to a head in his dealings with the new Persian Sassanid dynasty which

had arisen under Ardashir and his son Shapur. The Sassanids had

not only taken over the Parthian kingdom, but had extended Persian

control deep into Roman territory in the eastern reaches of the Roman

empire. When Alexander marched his army out to meet the Sassanids

in 232, the results were something of a standoff for both sides.

Sassanid kings Ardashir (224-240) and Shapur (240-270)

Two

years later Alexander led his armies out to expel the German armies

that had crossed the Rhine and had overrun eastern Gaul. He

crossed into Germany – and then offered to pay tribute to the Germans

rather than fight them to resolve the issue. The soldiers were

incensed – and plotted his removal and replacement by a soldier popular

among the troops. In 235 Alexander and his mother were both

murdered in a mutiny of his troops.

Maximinus Thrax

(235-238)

A Thracian peasant who was brought to

the imperial position by the military. He reversed Alexander's reforms

and restored military rule as the underpinning of the emperorship.

Marks the beginning of a period of decline of the Roman empire as contenders

to the throne vied in combat with each other. This permitted the

Allamanni and Franks to cross beyond the limes of the empire (along the

Rhine) in 236. In 237 the Goths crossed the Danube into the

Balkans at the other end of the Roman line of defence against the Germans.

Yet Another Lengthy Period

of Confusion (238-253)

The confusion of competing would-be

emperors backed by their own armies which started during the reign of Maximinus

only increased in the period after him. During the next 15 years

emperors came and went in rapid succession--with more than one figure claiming

that title at the same time.

Decius

(249-251)

201-251. Decius was one of those

short-lived imperial figures. He was a major persecutor of the Christians.

He ordered a general sacrifice to the emperor to be conducted around the

empire--and for those refusing to do so to be dealt with harshly.

Decius was killed in a battle to

stop the flow of the Goths--who were crossing the Danube at will.

Valerian (253-260)

193-260. He also ordered a massive round

of persecution of Christians.

As the Romans were pushed to the

defensive against the German onslaught against the Empire in the North,

the Persians were undergoing a revival of power under the new Sassanid

dynasty and began to pose a major threat to Roman power in the East.

The Sassanids laid claim to all the Asian provinces of Rome, and attacked

Antioch. In 259, Valerian, trying to organize a defense, was captured

in this battle. In 260 the Persians succeeded in capturing Antioch.

Valerian died in captivity in that same year.

Gallienus

(260-268)

Son of Valerian. During his rule

the chaos descending on Rome reached a peak. The Roman districts

in Germany beyond the Rhine were lost, never to be recovered. A Gothic

navy of 500 ships harrassed Asia Minor and even Greece itself--sacking

Athens, Corinth and Sparta. Roman legions had to operate pretty much

on their own because of the lack of power at the Roman political center.

Cassianius Latinius Postumus (259-269)

M. Cassianius Latinius Postumus was

not an emperor but a local Roman ruler during the chaotic reign of Gallienus.

Backed by the Roman legions of Gaul, Spain and Britain, he established

a provincial empire of his own in the West (Gaul). The regionalization

of power permitted the restoration in Gaul of security from the attacks

of the invading Germans.

Odaenathus ( -266)

Not an emperor--but another regional

Roman ruler during the reign of Gallienus. As governor of the East,

he drove the Persians from Asia Minor and Syria, even recovering Mesopotamia

for Rome. He ruled--as a sovereign by his own right as Prince of

Palmyra--Syria, Arabia, Armenia, Cappadocia and Cilicia. He was murdered

in 266.

Septimia Zenobia

(266-273)

Though the rulership of Odaenathus formally

went to his young son, Vaballathus, in fact it was his wife, Septimia Zenobia,

who ruled after him. She extended her rule into Egypt--and declared

the independence of Palmyran rule from Roman authority.

Aurelian (270-275)

212-275. Aurelian restored central

Roman authority, destroying Palmyran rule in 273 and bringing Zenobia to

Rome in chains. In 274 he brought an end to the independent Gallic

empire in the West, bringing Gaul back under direct Roman rule. He

rebuilt the defenses along the Danube. He even built fortifucations

around the imperial city of Rome itself--a sign of the trouble of the times.

In 275 he was assassinated by some

of his officers.

Probus (276-282)

Defeated the Franks and Alemanni and

secured the Rhine defenses again.

Carus (282-283)

In 282 Carus restored Armenia and Mesopotamia

to Roman rule and reestablished the old boundaries of Septimus Severus.

Diocletian

(284-305) Diocletian

(284-305)

235-313. Diocletian attempted

a number of reforms designed to strengthen the greatly weakened Empire.

He divided the Empire into two parts: Eastern and Western.

The Eastern part comprising Asia Minor and Egypt he himself ruled directly

from his capital in Nicomedia. The Western part comprising Italy

and Africa he assigned in 286 to Maximinian, "co-Augustus" with himself,

who was to rule from Milan.

In 293 he chose Galerius as his successor

as Caesar and Maximinian chose Constantius as his successor--freeing

themselves to their work as supreme princips or

Augusti. Thus

a quadripartite rule was established.

In 303, deeply worried about the

rising influence of the Christians in the Empire, Diocletian ordered a

major round of persecution against the Christians in his eastern territories.

This lasted through the rest of his reign--indeed until 313

In 305 both Diocletian and Maximinian

abdicated their rule, leaving power to Galerius and Constantius.

Diocletian retired to his huge villa at Salona (Split) in modern Croatia

and lived out the rest of his 8 years there.

Maximian (286-305)

Constantius I

Chlorus (305-311)

Joint rule with

Galerius : 305-311

Galerius (305-311)

Joint rule with

Constantius I Chlorus: 305-311.

Licinius (308-324)

Licinius was an Illyrian peasant who

rose through the ranks of the Roman Army--and in 308 was named "Augustus"

(junior ruler) by Galerius. In 311, with the death of Galerius, he

received Galerius's political holdings in the West. Two years later

he defeated in battle the Emperor of the East, Maximinius, and took his

holdings.

But Constantine had also been building

his strength as "Augustus" and despite their earlier friendship (Licinius

was even married to Constantine's half-sister Constantia) Constantine forced

Licinius to give up lands to him. Finally in 324 the two met in battle

and Licinius was stripped of his powers. The following year he was

executed on charges of conspiring against Constantine.

Constantine

the Great (311-337) Constantine

the Great (311-337)

273-337. Constantine was a Roman

Emperor ruling jointly with Licinius from 311 to 324 and solely thereafter

until his death in 336.

We remember him most importantly

for his conversion to Christianity in 312, which opened the way for the

adoption of Christianity as the official religion of Rome, and for his

establishing in 330 a new Roman capital in the East at Byzantium, just

across from Asia Minor.

He was originally a worshipper of

the Unconquered Sun, a widely popular religion in that time. Interestingly,

even as Constantine came to honor Christ, he retained loyalty to this god,

even establishing the first day of the week as the holy day: "Sun" day.

His conversion to Christianity came

in 312 at the Battle of Milvian Bridge--through a series of miracles and

vows which brought him to faith in Jesus Christ.

Within six months of his conversion

he was asked by the Donatists in North Africa to intervene in their dispute

with "apostate" bishops (ones who had at one point denied their faith under

the pressure of persecution) whose authority the Donatists no longer recognized.

Constantine did intervene--but found in favor of the restored bishops against

the Donatists, and ordered the Donatists to submit to the authority of

these bishops.

He went from there to become increasingly

active in imposing "order" on his new church--seeing this as his imperial

duty to God (as always had been the understanding of the Emperor's responsibility

to the empire: that is, to be the "defender of the faith").

He was responsible for calling the

Council of Nicea (325) to decide the dispute between Alexander, Bishop

of Alexandria and his presbyter, Arius--who had come to espouse a monarchian

or "unitarian" position. The Council itself decided in favor of Alexander--and

outlined the basics of the "Nicene Creed," which stood at the heart of

"Trinitarian" Catholic doctrine.

Though Constantine stood firmly behind

the Council and its decision, he himself remained quite tolerant of the

unitarian Arians--who were widely popular in the East (where the Nicene

"Trinitarian" decision itself was unpopular). Rumors were that he

himself had Arian sympathies--but kept them to himself in order to preserve

the religious unity of his domain.

Triumvirate of

Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans (336-350)

Upon Constantine's death in 337 the

empire was divided up among his three sons. They intrigued and fought against

each other--and others--until in 354 Constantius held position as sole

Roman emperor.

Constantius II

(354-361)

Constantius was a fervent Arian and

intimidated the bishops into an anti-Nicene position. At the same time,

pursuing religious conformity within his empire, he pushed the Christian

cause against paganism more forcefully than his father had--closing the

temples in 356 and removing the alter of Victory from the Roman Senate

in 357.

Julian (361-363)

Called the "Apostate" for his efforts

to end Christianity's religious monopoly and restore pagan worship to prominence

in Rome--even though he himself was raised in his youth as a Christian.

Julian was a nephew of Constantine

who had miraculously escaped the murderous intrigues that took the life

of most of the rest of his family in 337. Upon finally becoming emperor

himself, he disclosed his pagan loyalties and began to try to undo the

work of his Christian uncle Constantine and cousin Constantius. He

tried to substitute a new religion based on Platonism in which the Supreme

Being was identified with the Sun God Helios (akin to the popular Mithras).

He tried also to establish the same moral rigor for his faith that made

Christianity so respectable--and even copied the ecclesiastical organization

of the Christian church.

He did not directly persecute Christianity

but did remove Christianity's privileged position within the government

and forbade Christians from teaching in the public schools (in an effort

to bring the empire back to its pre-Christian traditions through the children).

But there was no real zeal among the populace for his reforms--which became

quickly apparent soon after he took over. This really closed the

book for traditional paganism.

Jovian (364-365)

Valentinian I

(West 364-375)

Western Roman Emperor

Valens (East 364-378)

Eastern Roman Emperor – brother of Valentinian

I.

In 370 Huns poured into Eastern Europe

from Asia, pressing the German-speaking Goths who inhabited the area. Emperor

Valens permitted the Goths (Visigoths or Western Goths) to settle inside

of traditional Roman lands, hoping that they would serve as a buffer to

the Huns. But soon both the Visigoths and their close kinsmen the Ostrogoths

(Eastern Goths) joined forces to defeat the Eastern Roman armies – establishing

Gothic autonomy within the Roman Empire. Eventually many of them were brought

into the Roman army in the hope that they would add vigor to the declining

Roman military power.

Gratian (West

jointly 375-383)

Joint Western Emperor (367-375)

with his father Valentinian until the latter's death in 375 and then with

his 4-year old brother Valentinian II.

The Empire was under constant attack

from Germanic tribes and he spent his rule mostly in Gaul fighting off

the Goths.

In 383 he marched his army against

the usurper of Roman power in Britain, Magnus Maximus. But his tooops

deserted him and he was murdered during his attempt to escape.

Valentinian

II (West jointly 375-383; solely 383-392)

Emperor of the West: jointly with

Gratian from 375 to 383 and solely thereafter until 392.

Theodosius I (East

379-392; East and West 392-395)

346?-395. Eastern Roman Emperor

from 379 to 392. After 392 until 395 he ruled both East and West.

He called the Christian Council of Constantinople.

Symmachus (345-410)

Quintus Aurelius Symmachus was not a

Roman Emperor--but was however a strong voice of the old pagan viewpoint

in the Roman Senate. His life of public service, his sterling moral

character and his wealth and personal influence made him an outstanding

spokesmen against the Christian ascendancy in Rome. In 382 he was

expelled from Rome after his strong protest over the removal of the statue

and altar to Victory in the Senate chamber. He was restored to influence

soon thereafter (prefect of the city of Rome), but proved to be still as

adamant as ever over this issue, appealing to to Emperor Valentinian to

restore these symbols of traditional Rome.

Stilicho (394-408)

Flavius Stilicho was not a Roman emperor--but

a mighty political force in the Empire that at times exceeded in power

the position of the Western Emperor.

He was born to a German Vandal officer

in the Roman army of emperor Valens. Stilicho himself joined the

imperial army and rose quickly up the ranks. In 383 he was sent by

Emperor Theodosius as a diplomatic envoy to the Persian King Sapor.

On his successful return he was brought into the imperial family by marrying

the Emperor's niece/adopted daughter, Serena.

In 385 he began a very successful

military career: in Thrace against the Goths, in Britain against

the Picts, Scots and Saxons, and along the German Rhine.

In 394, with his wife Serena, he

was appointed regent over the youthful joint emperor, Honorius – bringing

Stilicho into the thick of imperial politics. His main rival to his

deep political ambitions was Rufinus. In order to bring him down

Stilicho marched his army to the east to meet Rufinus, but then had Rufinus

assassinated. This made Stilicho the virtual dictator of the Roman

Empire.

In 396 he was drawn into Greece to

fight Alaric and the Visigoths--but

worked out a diplomatic settlement with Alaric instead.

By the year 400 he was consul – and

also father-in-law to Honorius.

In 401-402 he was called to action

again against Alaric (and Alaric's ally Radagaisus) – this time along the

Danube and in Italy. Once again he was successful in delivering the

Empire from this Barbarian threat through military victory and diplomatic

settlement. But in 405 Radagaisus again invaded Italy. This

time Stilicho starved Radagaisus to defeat.

In 408 Stilicho began to strengthen

his hold over Honorius with the marriage of his second daughter to the

Emperor. But then he was accused of plotting to overthrow his son-in-law

in order to establish himself as Emperor. Whatever the truth of the

matter, Stilicho fled to Italy, taking sanctuary in Ravenna. He was

brought out by a promise of safe-conduct – but was seized and executed nonetheless.

Honorius (394-423)

Emperor of the West, whose political

fortunes during the first 14 years of his rule were closely tied to Stilicho.

Arcadius (395-408)

c. 377-408. Emperor of the East, brother

of Honorius. It was during his reign that Alaric

invaded Greece.

Theodosius II

(East 408-450)

Valentinian

III (West 423-455)

|

The Israelites/Jews (Spiritual Pilgrim)

The Israelites/Jews (Spiritual Pilgrim)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges