12. GLORY

THE RISING SPIRIT OF NATIONALISM

CONTENTS

The French Second Empire The French Second Empire

The Founding of the Italian Nation-State The Founding of the Italian Nation-State

(the Risorgimento)

Bismarck and the New Germany Bismarck and the New Germany

Victorian England Victorian England

Tsarist Russia Tsarist Russia

The American Civil War ... but The American Civil War ... but

subsequent rise to industrial greatness

The Third Republic of France The Third Republic of France

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 1-25.

|

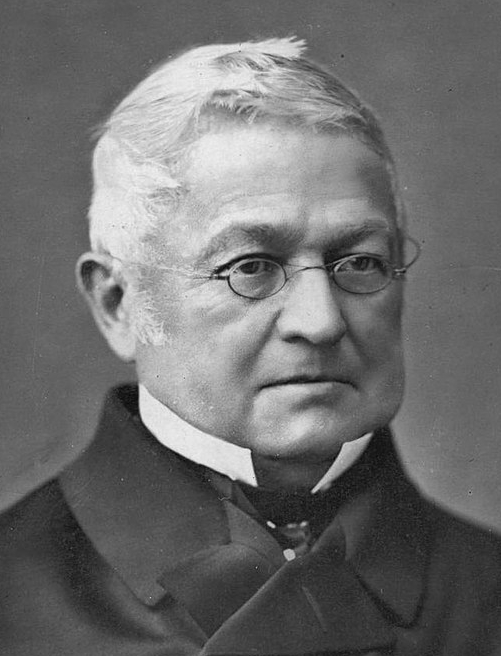

Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III)

Although Louis Napoleon was the nephew of the great Napoleon Bonaparte,

he was very different from him in temperament ... and ability.

Yet the name Napoleon was what brought him to his position of French

leadership ... and what forced him to move in directions that he was

really not able to manage successfully. He did his best when he

did little.

Because of the growing disillusionment among the middle and working

classes of France with their "citizen king" Louis-Philippe, a highly

romanticized cult of Napoleon (and thus things Napoleonic) began to

infect France during the 1840s. When Napoleon’s son died in 1832

(Napoleon II), the Bonapartists looked to Louis Napoleon to take the

lead. Being an individual with a love for the dramatic, Louis

Napoleon was more than happy to do so ... in 1836 and then again in

1840 attempting to overthrow the government of Louis-Philippe by

military action. Both efforts failed ... resulting in his brief

banishment in the first instance and his imprisonment in the

second. But while in prison he was active writing political

tracts which kept the Bonapartist dream alive. Then in 1846 he

escaped prison by disguising himself as a prison worker, fleeing

through Belgium to London ... where he waited for a new opportunity to

arise.

In 1848, with Louis-Philippe's abdication, that moment had

arrived. He moved immediately to France, but let Bonapartists

open the doors for him politically ... being elected to multiple seats

in the new (Second) Republic’s National Assembly. His name was

then put forward for the Presidency ... in which he was up against only

the conservative candidate, General Cavaignac, who had fired on Paris

protesters when Louis-Philippe was first in trouble. By a 5 to 1

margin, the popular vote in December (1848) went to Louis Napoleon as

the Republic’s new president.

The birth of the Second Empire

But once in office Louis Napoleon began to move on his dream of being

head of a restored Empire. The conservative majority in the

Assembly (which disliked the populism of Louis Napoleon) did the job

for him, passing voting restrictions which in essence took the vote

away from a third (the working classes) of the voting population.

Napoleon played on the anger of the lower classes by touring the

country and holding public meetings among the adoring masses. He

then challenged the Assembly to restore the votes to those taken off

the roles, which the Assembly refused to do ... giving the appearance

of Louis Napoleon as being the true champion of the people.

He was by this time ending his four-year term limit as president and

knew it was time to act. On the night of 1-2 December (1851) he

had officers arrest a large number of civil and military opponents and

awakened France the next morning to the news that the Assembly had been

dismissed, universal suffrage restored, and a new constitution was in

the making, one which would give the president (himself) virtually all

governing powers for a term of ten years.

The reaction to the news in Paris proved to be timid ... though

resistance in the French countryside was substantial. Then on

December 21, the French voted an overwhelming approval of the new

constitution ... and a year later also voted overwhelmingly to

re-designate the head of the country as Emperor rather than

President. And thus the French Second Empire was born (December

1852), with Louis Napoleon as Emperor Napoleon III.

For more on Louis Napoleon For more on Louis Napoleon

|

Napoleon III - French Emperor - Versailles Palace - December 1852

Napoleon III - French Emperor - Versailles Palace - December 1852

|

The glory years

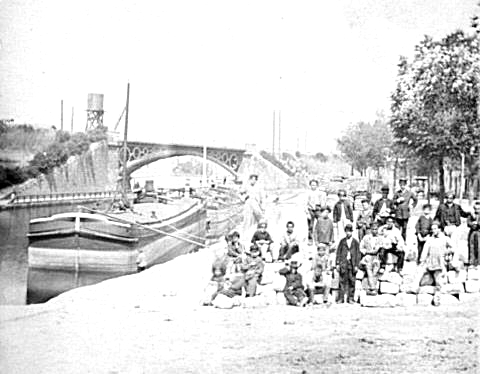

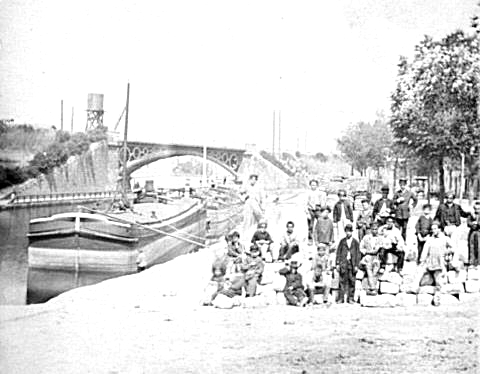

The amazing prosperity that followed in the next years settled the

French into a political calm not experienced in a long time. New

commercial banks were founded, canals dug, railroads laid out, and

steamships added to the French commercial fleet. The emperor and

his Spanish wife Eugénie were active in improving and increasing the

health, safety and nurture (hospitals, orphanages, convalescent homes)

of the French working class. The Paris capital was rebuilt

extensively by Baron Haussmann with new and elegant public and private

buildings, tree-lined boulevards, parks, bridges, public buses, a new

water system, sewers, paved streets, gas street lights, etc. ...

turning Paris into the most elegant city in the world.

The Crimean War (1854-1856)

Being a Napoleon, of course, the emperor could not avoid even in his

own mind being compared to his famous uncle, the fabled general of

old. Louis Napoleon felt compelled to measure up somehow.

And that meant military action in some form or other.

He

soon found his opportunity when Tsar Nicholas began pressuring the

Turkish "Sick Man of Europe" (the Ottoman sultan) to have himself named

as "Protector" of the Christian subjects and Christian places of

pilgrimage inside the Ottoman Empire. Napoleon saw this as a move

to replace Catholic supervision with Orthodox supervision ... and the

British saw this as simply a ploy of the Russian Tsar to seize land in

the Balkan Peninsula ... and even along the Mediterranean coast if

possible. Thus both France and Britain (and the smaller Italian

Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont) moved to support the Turkish sultan

against Russian aggression. When the Tsar moved Russian troops

into Moldavia and Wallachia, the allies responded with their own

counter-move against Russia (March 1854). Actually the Turks on

their own managed to turn the Russians back when they attempted to

march on Constantinople (Istanbul) ... and it looked as if the matter

had resolved itself as a standoff.

But the British were not content to let it end there, and decided to

carry the war to the Russians, in particular to Sevastopol in the

Crimea where a Russian naval fleet was based. The British wanted

to end any possibility that the Russians might get into a position to

challenge the British domination of the Eastern Mediterranean ... where

British commerce had to pass to reach India and the huge British

interests there. Thus the allies combined forces and landed about

60,000 troops in Crimea in order to seize the Russian naval base.

But they wasted valuable time getting moving once on land, allowing the

Russians to move their own troops into a strong, defensive

position. Thus the attack stalled ... and at Balaclava the attack

even turned into a grand disaster for them.1

Then a hard winter – for which the allies were totally unprepared – set

in, creating even more anguish and death than had the guns of the

Russians.

Fighting resumed the next spring, but it was not until September

that the Russian fortress at Sevastopol was finally taken by the

allies. Nonetheless the war dragged on through another winter ...

until finally in early 1856 the Russians called for a peace

settlement. The allies wisely accepted the request, for their own

citizens were tiring greatly from a war that seemed to yield nothing

but dead and wounded. Thus the powers gathered in March to sign

the Treaty of Paris (March 1856).

Overall, the war cleared the Black Sea of a Russian navy ... at least

for a while. It undercut the great power status of

Russia. It shattered the basic unity that had characterized

the Concert of Europe, not only isolating Russia among the Big Five

powers of Europe, but also undercutting Austria ... which had failed to

come to the aid of its formerly close ally Russia. Smarting from

this Austrian betrayal, Russia would return the snub when Austria found

itself in trouble, particularly in the face of a rising Prussian power

to the north in Germany. Also, although the Ottoman Empire came

out on the "winning" side, it clearly revealed that it did so only

because of the support of England and France. Indeed, it

highlighted the Ottoman Empire as the "Sick Man of Europe" ... inviting

various ethnic minorities in the Empire to begin to push for their own

national autonomy within, even independence from, the Ottoman Empire.

Yet most importantly for Louis Napoleon, it restored France to the

status of being the strongest continental power in Europe. It was

thus at this point that Emperor Napoleon III reached the height of his

popularity at home and glory abroad.

1This

was the event that inspired the English Poet Laureate Alfred Lord

Tennyson to write his famous poem, "The Charge of the Light Brigade."

British Commander Baron Raglan, Turkish Commander Omar Pasha, and

French Marshall Pelissier conferring during the Crimean War - 1854-1856

Interestingly,

Omar Pasha was born as Mihajlo Latas to a Serbian Christian military

family ... but in 1823 escaped to the Ottoman Empire to avoid a

corruption scandal, converted to Islam, then led Turkish troops in

putting down various Christian rebellions against Ottoman authority. During the Crimean War, he

led Turkish forces to victories against the Russians in the Danubian

provinces ... and also commanded the Turkish forces at the Siege of

Sevastaopol.

|

The Charge of the Light Brigade - by Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. (1894)

| Alfred Lord Tennyson would commemorate the event (December 1854) with the famous line "Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. " The neary suicidal charge against the canon and guns of the Russians at the Battle of Balaclava (October 25, 1854) resulted in the death and wounding of 40 percent of the British cavalry. |

The Russians defending Sevastapol against a British and French assault - 1854-1855 - by Franz Roubard

THE FOUNDING OF THE ITALIAN NATION-STATE

(THE RISORGIMENTO) |

Since

the fall of the Roman empire "Italy" was more a geographic designation

on a map of Europe than an actual political entity. Italy – like

Germany – was made up of a number of small but very independent states

... including the Pope’s own Papal States. Being so divided,

Italy was thus easy prey for the larger powers of Europe, Spain and

France ... joined eventually by Austria.

Italy got caught up in the political turmoil of the French Revolution,

especially when in 1796 Napoleon Bonaparte brought his French army into

the region and established something of a Republic which briefly

included most of Italy ... until a peasant reaction in Napoleon’s

absence returned Italy to its former status quo (including the

restoration of the Papal States and Austria’s dominance). But

once Napoleon took full power in France he returned to Italy (1800) and

brought quickly most of northern Italy again under French

control. He established in 1805 the title of "King of Italy" and

then had his troops seize the southern Kingdom of Naples (1806), adding

it to the Italian kingdom. In 1809 he completed the unification

of Italy by seizing Rome and the Papal States. At this point,

whether they were for or against Napoleon, Italians clearly understood

the importance – and the possibilities – of a unified Italian state.

When Napoleon was finally overthrown in 1815, Italy was divided into

nine states ... and efforts were made by Metternich and the ‘Big Five’

of Europe to restore Italy to its pre-Napoleonic social-cultural

status. But young Italians had little love for this

situation. Secret societies were formed, chief among them the

Carbonari, for the purpose of instituting a unified Italian state – by

force if necessary. But failed uprisings in 1820 and 1831 brought

great discouragement.

Nonetheless they persisted. And by the mid-1800s it appeared that

the possibilities of a unified Italian state hinged greatly on the

efforts of three key individuals: Giuseppe Mazzini, Count Camillo di

Cavour, and Giuseppe Garibaldi (with Victor Emmanuel II also important).

Mazzini

The young and energetic intellectual Mazzini, with strong republican

loyalties, was imprisoned in 1830, escaped, founded from his exile in

France an organization called Young Italy (1832) which spread rapidly

in membership and reach in Italy. He wrote countless pamphlets

brought secretly into Italy, outlining the noble nature of a

"Risorgimento" ("resurgence" or "rising again') ... involving the

political unification of all Italy. Thus it was that he himself

became something of its "soul" in the process.

The young and energetic intellectual Mazzini, with strong republican

loyalties, was imprisoned in 1830, escaped, founded from his exile in

France an organization called Young Italy (1832) which spread rapidly

in membership and reach in Italy. He wrote countless pamphlets

brought secretly into Italy, outlining the noble nature of a

"Risorgimento" ("resurgence" or "rising again') ... involving the

political unification of all Italy. Thus it was that he himself

became something of its "soul" in the process.

His cause was naturally opposed by others – those wanting a national

monarchy rather than a republic ... and those who wanted an independent

but federal Italy of unified states under the authority of the

pope. Indeed when the liberal-minded Pius IX took the papal

position in 1846 this seemed to be the most likely path that Italian

independence would take... until the huge support of many Italians for

the ideals of the 1848 revolutions sweeping Europe shocked the

pope. Pius was bitterly opposed to such democratic or republican

instincts and turned himself into a full reactionary.

Cavour ... and the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont

The uprisings of 1848 indeed brought movement, at least briefly, toward

the ideals of Mazzini and Young Italy. All through northern Italy

the Austrians and their local colleagues were driven from power, and at

first the rulers of Tuscany and Naples – and the pope – joined in

support of this nationalist movement. But strong disagreements as

to what direction Italy was to take next crippled the movement, and

Naples and the Papal States pulled out of the movement

altogether. This left only the liberal-minded King Charles Albert

of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont to continue the battle as the

Austrians and their colleagues regained their positions in northern

Italy. By 1849 the Austrians had defeated Charles Albert and his

smaller army ... and the effort on behalf of Italian independence

seemed to have come to an end. But the Italian hopeful would not

forget the sacrificial effort of Sardinia-Piedmont in support of the

cause.

The uprisings of 1848 indeed brought movement, at least briefly, toward

the ideals of Mazzini and Young Italy. All through northern Italy

the Austrians and their local colleagues were driven from power, and at

first the rulers of Tuscany and Naples – and the pope – joined in

support of this nationalist movement. But strong disagreements as

to what direction Italy was to take next crippled the movement, and

Naples and the Papal States pulled out of the movement

altogether. This left only the liberal-minded King Charles Albert

of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont to continue the battle as the

Austrians and their colleagues regained their positions in northern

Italy. By 1849 the Austrians had defeated Charles Albert and his

smaller army ... and the effort on behalf of Italian independence

seemed to have come to an end. But the Italian hopeful would not

forget the sacrificial effort of Sardinia-Piedmont in support of the

cause.

A tired Charles Albert turned his throne over to his son, Victor

Emmanuel II (1848), who continued his father’s liberal policies.

Best of all, he had the wisdom in 1854 to pick as his prime minister the highly

capable Cavour. Cavour understood that Italy’s destiny was

closely connected to Sardinia-Piedmont’s leadership and immediately set

himself to the task of building up the social muscle (industrial,

commercial, military) of the kingdom. He also understood the

importance of diplomatic connections ... and thus engaged

Sardinia- Piedmont fully in the Crimean War as ally with France and

Britain. Cavour even sent his attractive cousin, the Countess

Castiglione, to woo (successfully) Napoleon III.

A tired Charles Albert turned his throne over to his son, Victor

Emmanuel II (1848), who continued his father’s liberal policies.

Best of all, he had the wisdom in 1854 to pick as his prime minister the highly

capable Cavour. Cavour understood that Italy’s destiny was

closely connected to Sardinia-Piedmont’s leadership and immediately set

himself to the task of building up the social muscle (industrial,

commercial, military) of the kingdom. He also understood the

importance of diplomatic connections ... and thus engaged

Sardinia- Piedmont fully in the Crimean War as ally with France and

Britain. Cavour even sent his attractive cousin, the Countess

Castiglione, to woo (successfully) Napoleon III.

Now, in alliance with France, Cavour was ready to move against Austria

in northern and central Italy. He cleverly drew Austria into

declaring war (1859) to which France and Sardinia-Piedmont responded by

routing the Austrian forces at Magenta and Solferino (June).

Then, just as Austria was about to be run out of Italy, Napoleon III,

seeing his own armies badly bloodied by the action, decided to conclude

his own separate armistice with the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph,

ignoring his promise to Victor Emmanuel to fight until Austria was run

out of all of Italy. However, in its treaty with France, Austria

ceded much of its holdings in northern Italy to Sardinia-Piedmont ...

but was allowed to keep Venice and its large holdings in the northeast.

While this was a cruel blow to Cavour ... it was also a hugely foolish

move on Napoleon’s part. Napoleon did get the regions of Nice and

Savoy added to France (given up by Sardinia-Piedmont as part of the

deal). But his actions so strongly in favor of Austria raised

questions about his reliability as an ally and as a player in Europe’s

diplomatic games. It also seemed in the eyes of liberal French to

be a betrayal of the hope of a spread of liberal political philosophy

to the rest of Europe ... and to Italy in particular. And on the

other hand the alliance with Cavour, and his clear goal of absorbing

all of Italy (including the Papal States) into a liberal Italy,

alienated Napoleon III from the strongly Catholic instincts of the

French countryside. His Italian policy would thus mark the

beginning of Napoleon III’s political decline.

For Cavour however, things worked out better. Inspired by his

actions, a number of Italian states in northern Italy took the

initiative themselves in 1860 to oust their Austrian overlords and

declare their union with Sardinia-Piedmont.

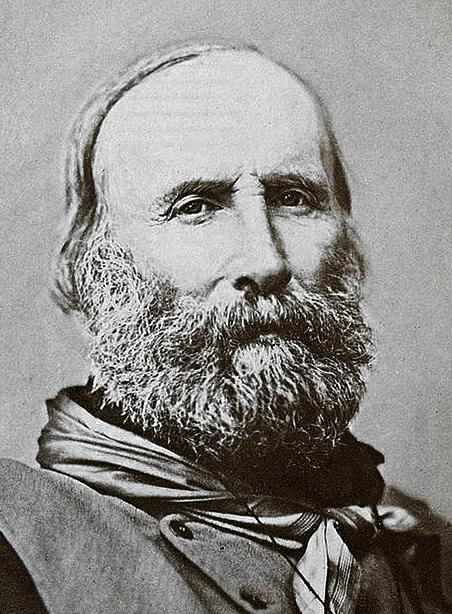

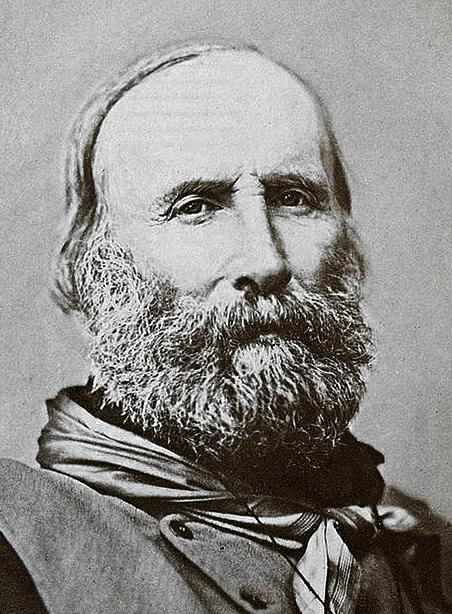

Garibaldi

At the same time (1860) activity of the same nature was stirring in the

south of Italy. At its head was the adventuresome Garibaldi, a

long-time rebel in favor of political liberalism, who had escaped to

South America after a failed uprising in Genoa in 1830 and there

learned the art of guerrilla warfare. He returned in 1847 in time

to participate in the 1848 uprising, put down by Napoleon III, which

forced him to flee Italy a second time. He made a small fortune

in America and returned to live on a small island off the coast of

Sardinia in 1854. Then when in 1859 things began moving again in

the form of a revived Italian nationalism, he organized in Naples a

small army of ‘Red Shirts’ and in 1860 moved them to Sicily and then,

accompanied by Victor Emmanuel, to Naples to end the Bourbon Kingdom of

the Two Sicilies ... and bring the region into union with Victor

Emmanuel’s kingdom. In 1861 a new Italian national parliament

then met at Turin to organize the new Kingdom of Italy ... and put it

to a vote of the Italian people. By an overwhelming majority, the

Kingdom and its constitution ... and Victor Emmanuel as its king ...

were approved by the people.

At the same time (1860) activity of the same nature was stirring in the

south of Italy. At its head was the adventuresome Garibaldi, a

long-time rebel in favor of political liberalism, who had escaped to

South America after a failed uprising in Genoa in 1830 and there

learned the art of guerrilla warfare. He returned in 1847 in time

to participate in the 1848 uprising, put down by Napoleon III, which

forced him to flee Italy a second time. He made a small fortune

in America and returned to live on a small island off the coast of

Sardinia in 1854. Then when in 1859 things began moving again in

the form of a revived Italian nationalism, he organized in Naples a

small army of ‘Red Shirts’ and in 1860 moved them to Sicily and then,

accompanied by Victor Emmanuel, to Naples to end the Bourbon Kingdom of

the Two Sicilies ... and bring the region into union with Victor

Emmanuel’s kingdom. In 1861 a new Italian national parliament

then met at Turin to organize the new Kingdom of Italy ... and put it

to a vote of the Italian people. By an overwhelming majority, the

Kingdom and its constitution ... and Victor Emmanuel as its king ...

were approved by the people.

his

left the question of Venice (still under the Austrians) and the status

of Rome and the Latium region unanswered. Wars elsewhere would

soon provide the answers. When in 1866 Prussia defeated Austria

in a struggle over German leadership, Austria was forced to give Venice

(and the entire region of Venetia) over to the new kingdom of Italy as

part of the peace agreement. Then when Prussia engaged France in

war in 1870, Napoleon III was forced to pull his troops out of Rome,

and the Pope lost his military protector. This allowed Victor

Emmanuel then to hold an Italian plebiscite on the matter, with a

majority of Italians voting in favor of attaching both Rome and Latium

to the Italian Kingdom. This then allowed him to seize Rome and

make it his new capital city, minus a very small area inside of Rome

left to the Papacy – "Vatican City."

Thus it was that the Italian dream had just been fulfilled. The

Italians now had their own kingdom, with Rome as its grand capital.

Pius IX (pope 1846-1878) fights back.

The huge political loss by Pius of the Papal States to the new Kingdom

of Italy turned him from something of a social Liberal to a very

conservative – most would even say highly reactionary – Catholic

leader. He excommunicated the Italian King Victor Emmanuel and

the rest of the Italian political leadership for how they had

terminated the Church's ability to carry out its long-standing

responsibilities.

But at least the loss freed Pius to turn his attention to strictly

religious matters, although he – and the popes that would follow for

the next half century – remained deeply opposed politically to the new

Italian state ... and would denounce it at every opportunity.

Early on Pius knew how to reach the hearts of Catholics everywhere –

whether they be Italian, Spanish, Polish, Irish, German, Austrian,

Belgian, French, American etc. – with his efforts in 1848 to elevate,

through a papal encyclical, Jesus's mother Mary to the status of being

totally sinless, most notably untouched by sexual intercourse,2

having brought forward the Christ Child through a process of

"immaculate conception." And being thus sin-free (from birth to

death) she was herself well-situated to be sought devotedly for divine

intercession on behalf of a confessing sinner.

However, this in turn raised the question: does the pope have the

right to decide such theological matters through the simple means of

papal encyclicals – of which Pius had been issuing many? Thus in

1869 a council (the First Vatican Council) was called to decide the

matter. And indeed it did. When the Council concluded its

work the following year, it had confirmed very strongly the doctrine of

"papal infallibility." The pope's words issued ex cathedra

carried the full weight of Catholic Truth in all matters of faith and

morals. Period.

But would this bold step forward of Catholic authority hold back the growing Secular trend clearly overtaking the West?

And what about the rising spirit of nationalism? National

loyalties were clearly growing ever-stronger than traditional Christian

loyalties. True, Westerners continued to identify themselves as

"Christians." But what they truly seemed ready to stand on – and

even die for – was their identities as Italians, Spanish, Polish,

Irish, etc. Christian loyalties by no means held anywhere near

the same position in the hearts of Westerners that rising national

loyalties now did.

2This

inevitably raised the old question: who exactly then were the

brothers and sisters of Jesus mentioned in Scripture (Mark 3:31-35,

Mark 6:3, Galatians 1:19, etc.)?

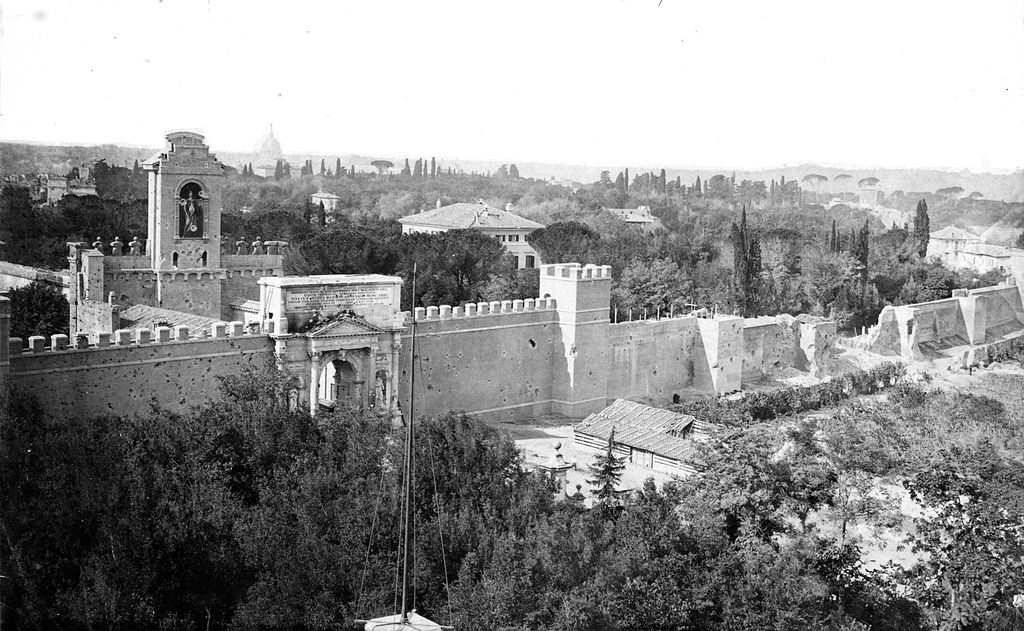

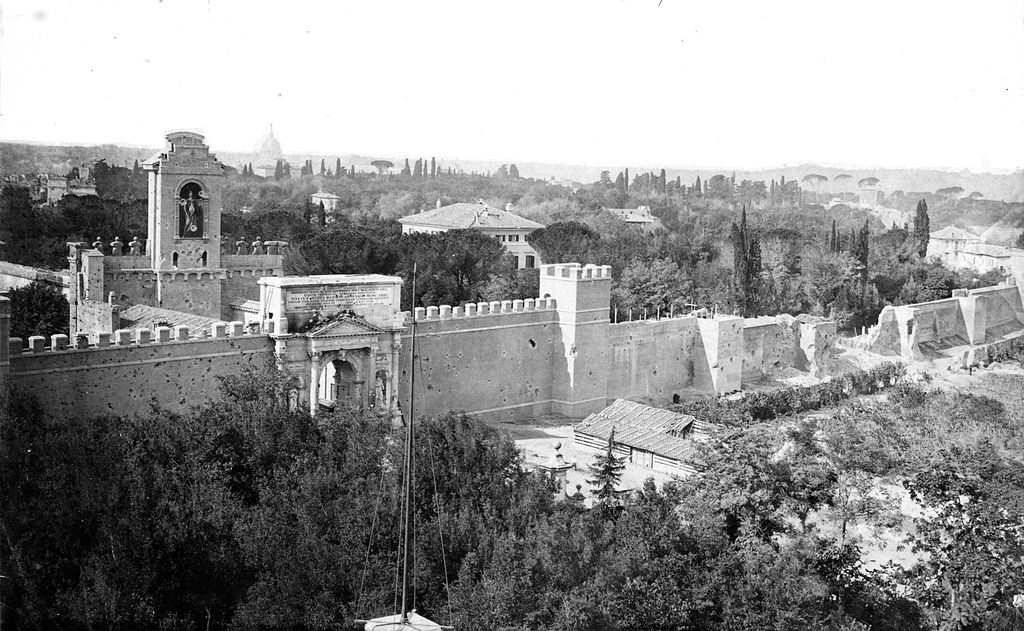

Victor Emmanuel's troops forcing their way into Rome - September 20, 1870 -

by Carlo Ademollo (1880)

Museo del Risorgimento - Milan

A photo of the breach in Rome's Aurelian walls where Victor Emmanuel's troops entered Rome

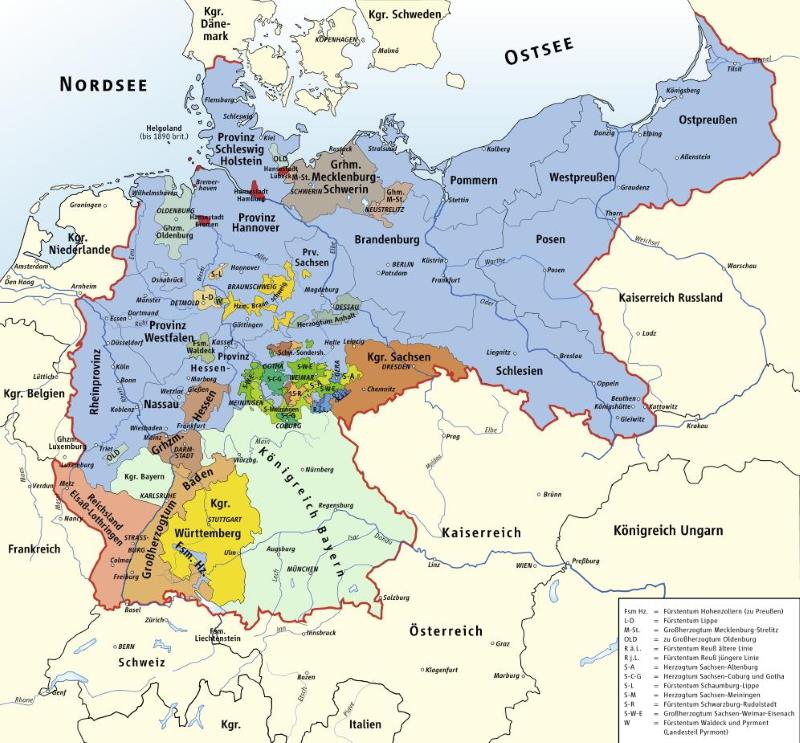

BISMARCK AND THE NEW GERMANY |

|

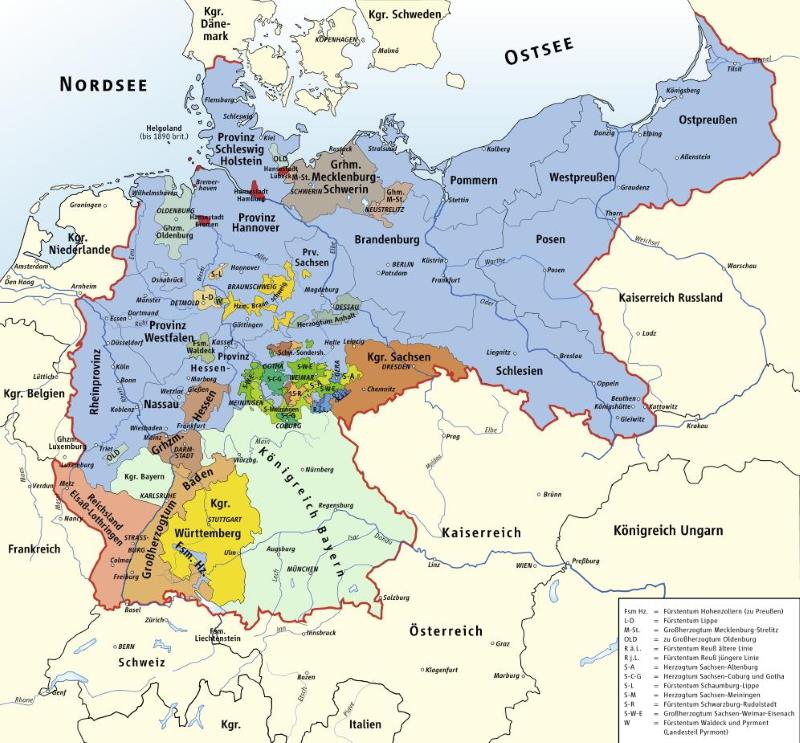

The Zollverein

As Italy had formerly been, Germany had long been more a geographic

designation on the map of Europe than a single society.

Linguistically the German language (in the form of many quite distinct

dialects) had been something of a unifying factor ... thanks in great

part to Luther’s German Bible. But politically, Germany had long

been split into a multitude of competing German states large and small

... some 300 of them! Napoleon had forcibly consolidated this

vast number into 39 German states ... a configuration that was retained

even after Napoleon’s defeat. But that meant that in the early

1800s there were still 39 German states continuing to compete

politically and economically, crippling German power.

A move towards union occurred when after the Napoleonic wars Prussia

started to liberalize the tariffs among the German states ruled by the

Hohenzollern king of Prussia. But other German states were

invited to join Prussia in some kind of expanding customs union.

This finally led in 1834 to the creation of a grand customs union or

Zollverein. Initially the Zollverein included 18 states.

Austria was not part of the membership (Austria was unwilling to lower

its high protective tariffs ... and Metternich was opposed to such a

link with Prussia). But over the years other German states joined

... until by the early 1850s Austria was the only German state outside

the Zollverein. Thus Germany was taking shape as a single entity

... at least economically. But such economics easily registered

itself politically.

|

|

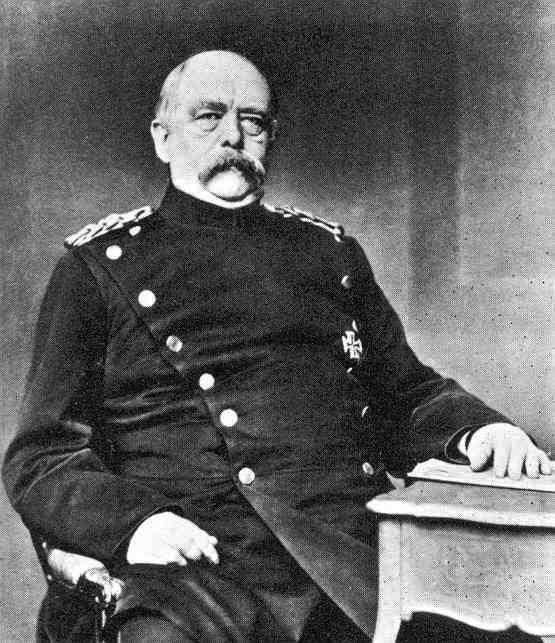

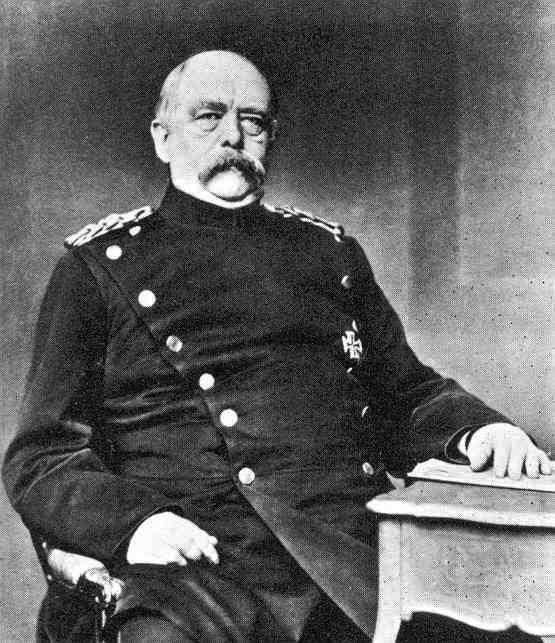

Bismarck vs. the German Liberals

The son of a Prussian Junker (minor nobleman), Otto von Bismarck came

to public attention first as a delegate to the Prussian assembly or

Diet that the Prussian king Frederick William IV (Friedrich Wilhelm IV) had called in 1847 in

response to liberal demands. He stood out from the liberals in

his strong defense of the sovereign rule of the Hohenzollern ... and in

his belief that only the Hohenzollern monarchy had the call to unite

all of Germany. In 1851 he was a Prussian representative to the

Diet of the Austrian-dominated Germanic Confederation where he showed

himself unwilling to bow to the Austrian domination of German

politics. To Bismarck, only Prussia had the makings of true

German leadership. He made his views well known not only to

Austria and the rest of the German world, but also to Frederick

William, whom he regularly consulted with in Berlin.

The son of a Prussian Junker (minor nobleman), Otto von Bismarck came

to public attention first as a delegate to the Prussian assembly or

Diet that the Prussian king Frederick William IV (Friedrich Wilhelm IV) had called in 1847 in

response to liberal demands. He stood out from the liberals in

his strong defense of the sovereign rule of the Hohenzollern ... and in

his belief that only the Hohenzollern monarchy had the call to unite

all of Germany. In 1851 he was a Prussian representative to the

Diet of the Austrian-dominated Germanic Confederation where he showed

himself unwilling to bow to the Austrian domination of German

politics. To Bismarck, only Prussia had the makings of true

German leadership. He made his views well known not only to

Austria and the rest of the German world, but also to Frederick

William, whom he regularly consulted with in Berlin.

In 1857, when Frederick William was incapacitated by a massive stroke,

his brother William (or Wilhelm) took over Prussian rule as

Regent. But Wilhelm was of a more liberal mind-set and found

Bismarck’s politics so challenging to the prevailing liberal political

mood that in 1859 he sent Bismarck to Russia as ambassador. This

effectively removed a frustrated Bismarck from the unfolding drama

taking place in Italy and central Europe. But Bismarck used his

time "on ice" in St. Petersburg to good effect, learning more about the

intricacies of European diplomacy and building up a relationship with

the Russian court that would later serve him well. He would also

use that time to develop a close political relationship with Prussian

generals von Roon (Prussian Minister of War) and von Moltke (Prussian

Military Chief of Staff). Then in 1862 Bismarck was sent to Paris

as Prussian Ambassador, using his time there to become acquainted with

the personal traits of Napoleon III ... and in a long visit to London,

to familiarize himself with Britain’s chief politicians, Prime Minister

Palmerston, Foreign Secretary Russell and Conservative Party leader

Disraeli.

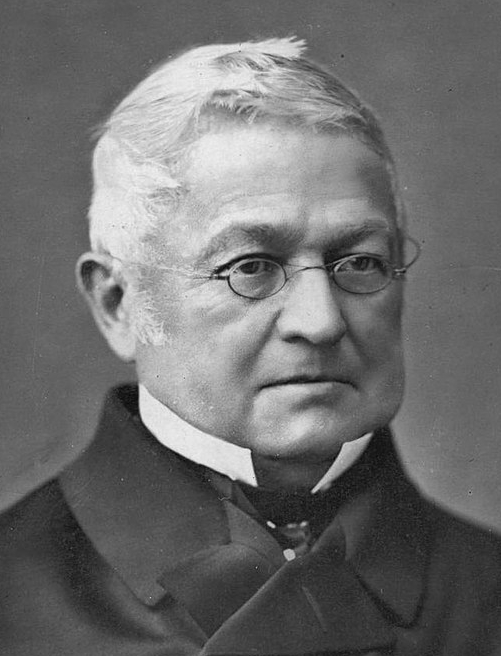

Friedrich

Wilhelm IV

Wilhelm I

The situation in Berlin began to swing in Bismarck’s favor when in 1861

Friedrich Wilhelm died and Wilhelm I became fully Prussian king ... and

found himself increasingly at odds with the Liberals in the Prussian

Diet. A crisis developed in 1862 between Wilhelm and the Diet

when the Liberals refused to fund the strengthening of the Prussian

army. The situation reached a point where Wilhelm was ready to

abdicate, when Bismarck, called to Berlin by Roon, arrived in time to

talk him out of it. At this point Wilhelm was ready to entrust

the strong-willed Bismarck with the position of president of his

ministry (effectively, prime minister or chancellor). Now

Bismarck could get to work building his long-sought united Germany

under Prussian command. With Roon and Moltke at his side,

Bismarck was about to show Europe how the game of politics and

diplomacy is supposed to be played.

With respect to the Liberals’ unwillingness to provide funding for the

military, Bismarck simply ignored the Prussian constitution and

continued to collect taxes on the basis of earlier legislation ...

infuriating the Liberal Diet, which however seemed to have no answer to

the overbearing Bismarck. Bismarck then tightened supervision of

the press, causing him even greater unpopularity. But neither

Bismarck – nor Wilhelm – were slowed up by popular opposition, even

when a new Diet came to office with an even greater Liberal majority.

Ignoring his liberal opposition, Bismarck had moved to strengthen greatly the Prussian military, explaining that:

Germany looks not to the

liberalism of Prussia, but to its power. ... The great questions of the

time cannot be resolved by speeches and parliamentary majorities – that

was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849 – but by iron (Eisen) and blood (Blut).

For the next four years (1862-1866) he was unquestionably the most hated person in Germany. But that was about to change.

|

A meeting of the German Confederation - 1863

|

The Schleswig-Holstein question

and the Austro-Prussian War

(1863-1866)

Bismarck was looking for some pretext to put Austria

to the test before the watchful eyes of the rest of Germany. In

1863 he found his opportunity when Frederick VII of Denmark died ...

and a dispute arose over who should inherit the throne ... and in

particular the Danish duchies of German-speaking Holstein and Schleswig

(the southern half also with a German-speaking population). When

the new Danish king Christian IX moved under a rising spirit of Danish

nationalism to fully annex Schleswig, Bismarck reacted to this insult

to the equally strong spirit of German nationalism and got Austria to

join him (1864) in invading Denmark and forcing Christian to give up

both provinces. Now the question remained of who should get which

of the two duchies. Ultimately (1865) Austria took Holstein and

Prussia took Schleswig.

But, as Bismarck anticipated, Austria began to encourage a German duke

to claim the right to rule the duchies ... giving Bismarck opportunity

to depict Austria as trying to stir up liberal troubles in northern

Germany. Claiming this to be simply a defensive move, Bismarck

ordered his Prussian troops into Austrian-occupied Holstein. The

Austrians resisted ... and Bismarck (with his carefully cultivated

Italian allies moving against Austria in Italy) easily crushed a

divided Austrian army at Königgrätz (or Sadowa).

By this time the Germans had been stirred to intense patriotic

nationalism (and Bismarck had become Germany’s national hero, no longer

its most hated citizen!). But Bismarck played a cool hand by

refusing to let Prussian troops do any more damage to a crushed

Austrian ego. To add further insult to injury, Bismarck was

relatively generous to his defeated enemy, increasing greatly Prussia’s

political stature. In victory Prussia received additional German

lands ... but none taken from Austria. Austria was forced only to

pay a small indemnity to Prussia and to accord full rights to Prussia

in Schleswig-Holstein. However Italy did receive Venetia from

Austria as its reward for allying with Prussia in the conflict.

Austria also had to agree to the dissolution of the German

Confederation – which Austria had long dominated – its place taken by a

new huge North German Confederation – in which clearly Prussia would

dominate (Austria was excluded from membership). According to the

new constitution, member states would retain full sovereignty in

domestic matters. As a federal union it would possess a legislature of

an upper house (Bundesrat) representing the various member states and a

lower house (Bundestag) representing the German voting public.

Also the new North German Confederation would be headed by the Prussian

king, who would also be charged with the conduct of the confederation’s

foreign diplomacy.

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871)

Now it was time for Bismarck

to bring the southern German states (still excluding Austria) into his

newly forming Germany. Napoleon III would unwittingly facilitate

that move. Napoleon had been expecting to be a Prussian ally in

the conflict with Austria. He thus expected in compensation the

extension of French territory in the south of Germany all the way to

the Rhine River. But the war was over so quickly that he lost out

on the payoff. He then complained that at least his neutrality

deserved him such a reward. Bismarck tricked him into putting his

demand in writing ... and then showed it to the southern German states,

infuriating them and driving them into Prussia’s arms as protector

against such French ambitions. Now all Bismarck needed was an

event – a French attack on Germany – to spark just those conditions,

and complete the unification of all Germany.

That event was to soon develop around the matter of naming a successor

to the Spanish throne after Queen Isabella was deposed by a Spanish

revolt in 1868. A Hohenzollern Prussian prince Leopold was one of

several possibilities ... causing Napoleon and France deep concern

about a Prussian encirclement from the south and the east. When

Leopold withdrew his name from the list, it looked as if Bismarck was

not going to get the confrontation he was looking for. Napoleon

was content to leave matters at that. But his meddlesome wife

pushed for a Prussian pledge that no Hohenzollern would ever become a

candidate for the Spanish throne. Wilhelm refused the request ...

and then sent a telegram from Ems (where Wilhelm was vacationing) to

Bismarck briefly explaining the event. Bismarck reworked the

telegram a bit, making the French demand appear insulting to German

pride ... and Wilhelm’s reply insulting to French pride. He then

sent the revised Ems telegram for publication in the official

newspaper. It had the desired effect of stirring an already sore French

national pride into full fury ... leading Napoleon and the French

Parliament to declare war in mid July 1870. But the Germans were

now united behind Bismarck and ready to take on their old national foe,

Napoleonic France.

Now appeared the huge differences in levels of political skill

separating Bismarck and Napoleon III. Napoleon was led by the

passions of the French, who believed that their troops would be in

Berlin in a matter of mere weeks. Bismarck was the master of

German opinion, not its servant. Bismarck had over the years

carefully prepared his military for this major super-power

confrontation. Napoleon’s France was unprepared ... its officers,

its equipment, its numbers of trained soldiers. Diplomatically,

Bismarck had carefully laid the groundwork so that France would find

itself isolated when it looked to former allies for help. The

Austrians had been neutralized, not just by the shock of their loss to

the Prussians in their recent war but because they were afraid that the

Russians, who Bismarck had been cultivating as allies, might join any

conflict against them. And Victor Emmanuel’s Italy was now

clearly a Prussian ally, understanding that with France occupied in a

war with Prussia, the Pope would lose French protection ... and thus

the Papal States would be ripe for the plucking by the new Kingdom of

Italy. In short, Napoleon stood no chance of success in any

conflict with Bismarck’s Germany.

It did not take long for German superiority to register itself. A

French army sent out to hit the Germans was itself hit in a series of

battles that within a month had it surrounded (August). A second

French army was sent out to relieve the first French army and it was

surrounded and destroyed (September 2) at Sedan, including Napoleon III

who was captured trying to lead the French attack.

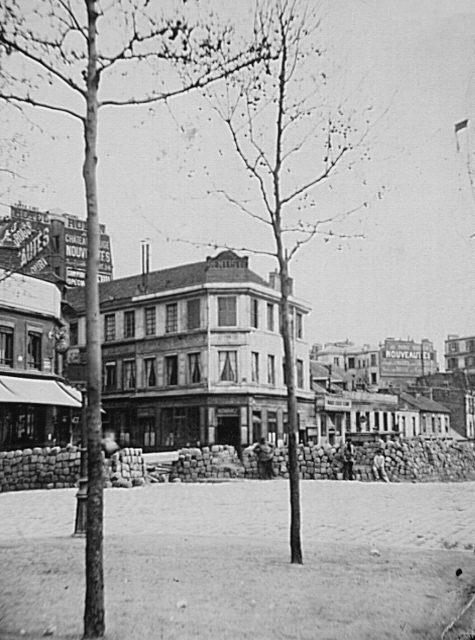

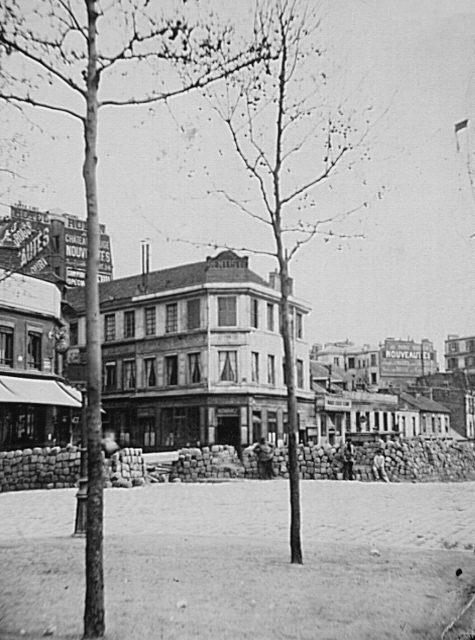

The news of the French defeat at Sedan was the signal for French

politicians in Paris to take charge, to declare a provisional

government or "Government of National Defense" of a new Third Republic

(Napoleon III’s Second Empire had simply vanished). Everyone

expected the French and Germans at this point to meet for

negotiations.

But Bismarck was not finished. He ordered his troops to march on

Paris, which was fully surrounded before the end of the month.

The French were now up in arms all around the country and the war

dragged on. But Paris was soon starving and France was becoming

increasingly chaotic. When in early February (1871) it became

obvious that Gambetta’s French troops would not be able to break the

German encirclement of Paris, the provisional government was finally

forced to surrender.

Europe was shocked ... having expected the famous French army to make

short work of the German army – rather than the opposite. The

results for France were disastrous. As part of the terms of peace

France was required to turn over to Germany the border regions of

Alsace and Lorraine, pay a large indemnity to Germany, and have the

northern half of France occupied by German troops until the indemnity

was paid up. To add further insult to France, a month earlier

Wilhelm had been crowned the Emperor of the new German (Second) Empire

at the Versailles Palace outside of Paris.

|

French Soldiers in the

Franco-Prussian War 1870-71

Providence, RI, Brown

University

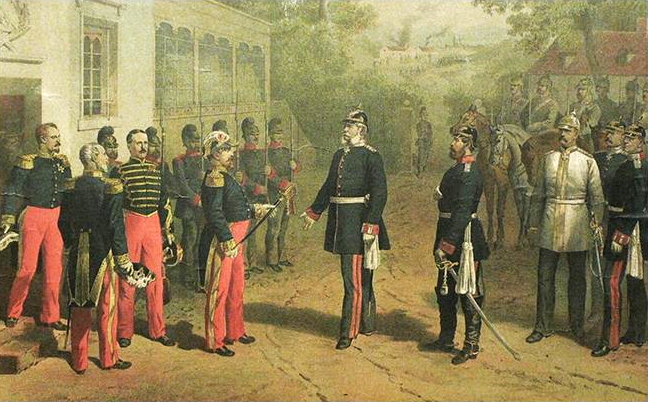

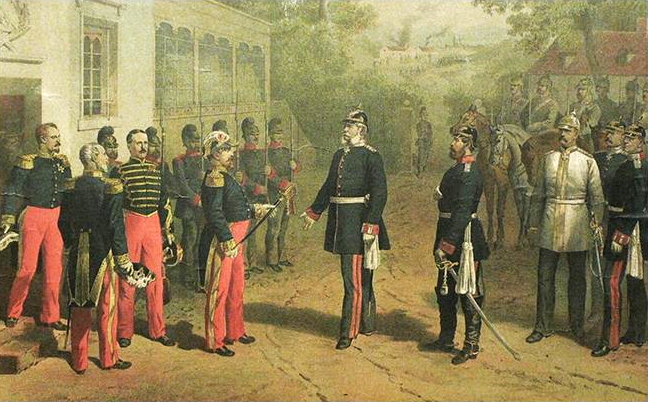

Napoleon III Surrenders to Wilhelm after the Battle of Sedan - September 1870

Sammlung Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte - Berlin

January 1871 - Wilhelm declared Emperor of the new German Second Empire (Reich)

at the Versailles Palace just outside of Paris

In

1837 an 18-year-old Victoria succeeded to her uncle William IV’s throne

as Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Any

doubts that she would be able to live up to the heavy duties laid on

her by this inheritance were soon dispelled. She was studious in

her approach to problems, devoted to the welfare of Great Britain and

its people and wise in her choice of counselors. Consequently, she gave her people a long reign devoid of the kinds of

turmoil that shook the countries of continental Europe. In

1837 an 18-year-old Victoria succeeded to her uncle William IV’s throne

as Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Any

doubts that she would be able to live up to the heavy duties laid on

her by this inheritance were soon dispelled. She was studious in

her approach to problems, devoted to the welfare of Great Britain and

its people and wise in her choice of counselors. Consequently, she gave her people a long reign devoid of the kinds of

turmoil that shook the countries of continental Europe.

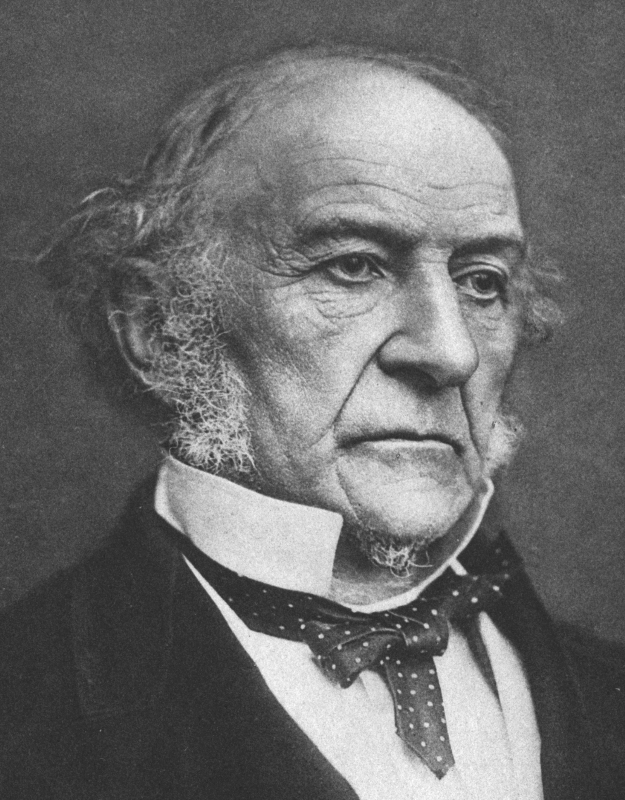

Parliamentary leaders

Several major political figures stood out during this long period of

British politics. In her early years the person who influenced

her most was her German cousin and husband Albert (married in 1840),

who shared her interests, her wisdom and her political skills.

Victoria and Albert - 1854 (the era of the Crimean War)

Also, in

cooperation with whichever political party held the majority of seats

in Parliament, she worked with a variety of influential prime

ministers. In the early days that was principally the Whigs

Viscount Melbourne and Viscount Palmerston ... and the Tory Robert

Peel. After Albert’s death in 1861 several other figures would

play a key role during her reign: the Conservatives Benjamin Disraeli

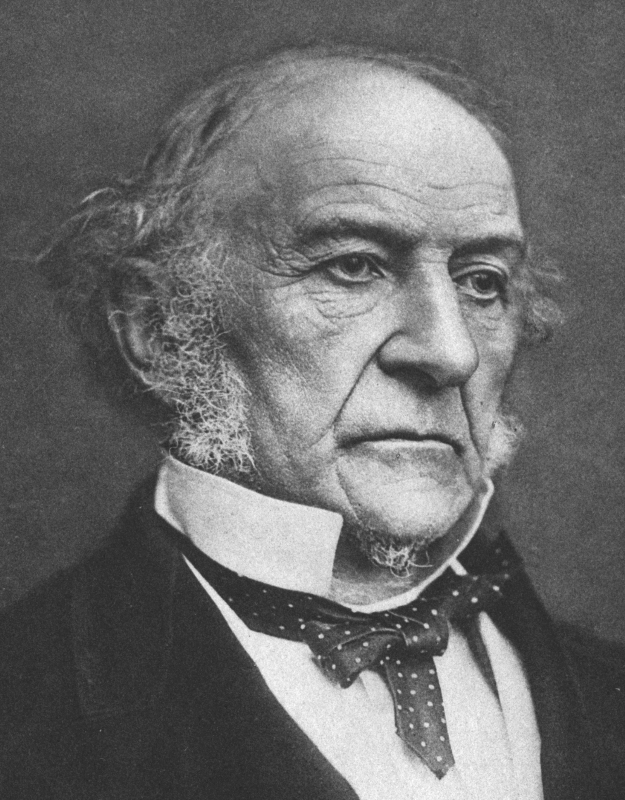

and the Marquess of Salisbury and the Liberal William Gladstone.

Mostly the policies of these men differed only in detail and not in

philosophy (though personally Victoria did not much care for

Gladstone). Disraeli and Gladstone both worked hard over their

long careers to bring British politics closer to the democratic

ideal ... and to defeat the other (their personal rivalry was

relentless). And both men seemed simply to alternate back and

forth, in

and out of power, as either Chancellor of the Exchequer (head of the

treasury) or Prime Minister, from approximately 1852 to 1880.

The Liberal Party Leader Gladstone

The Conservative Party Leader Disraeli

With the death of Disraeli in 1881, his place at the head of the

Conservative Party was taken by Salisbury, a member of the House of

Lords, who then alternated with Gladstone (who died in 1898) until

shortly after Victoria’s death in 1901.

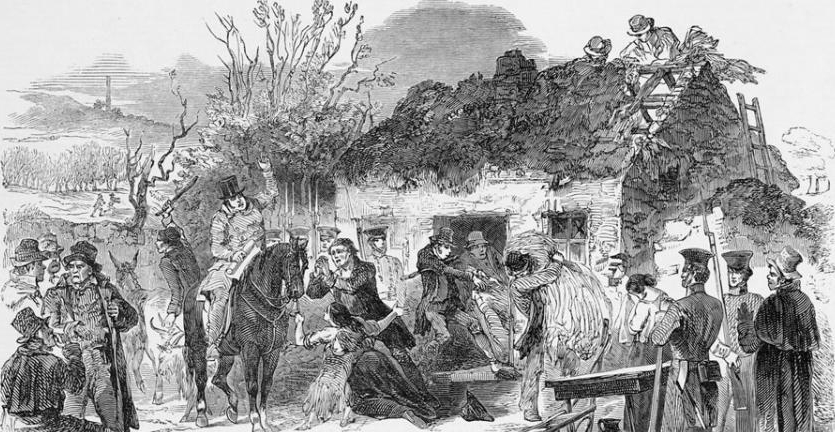

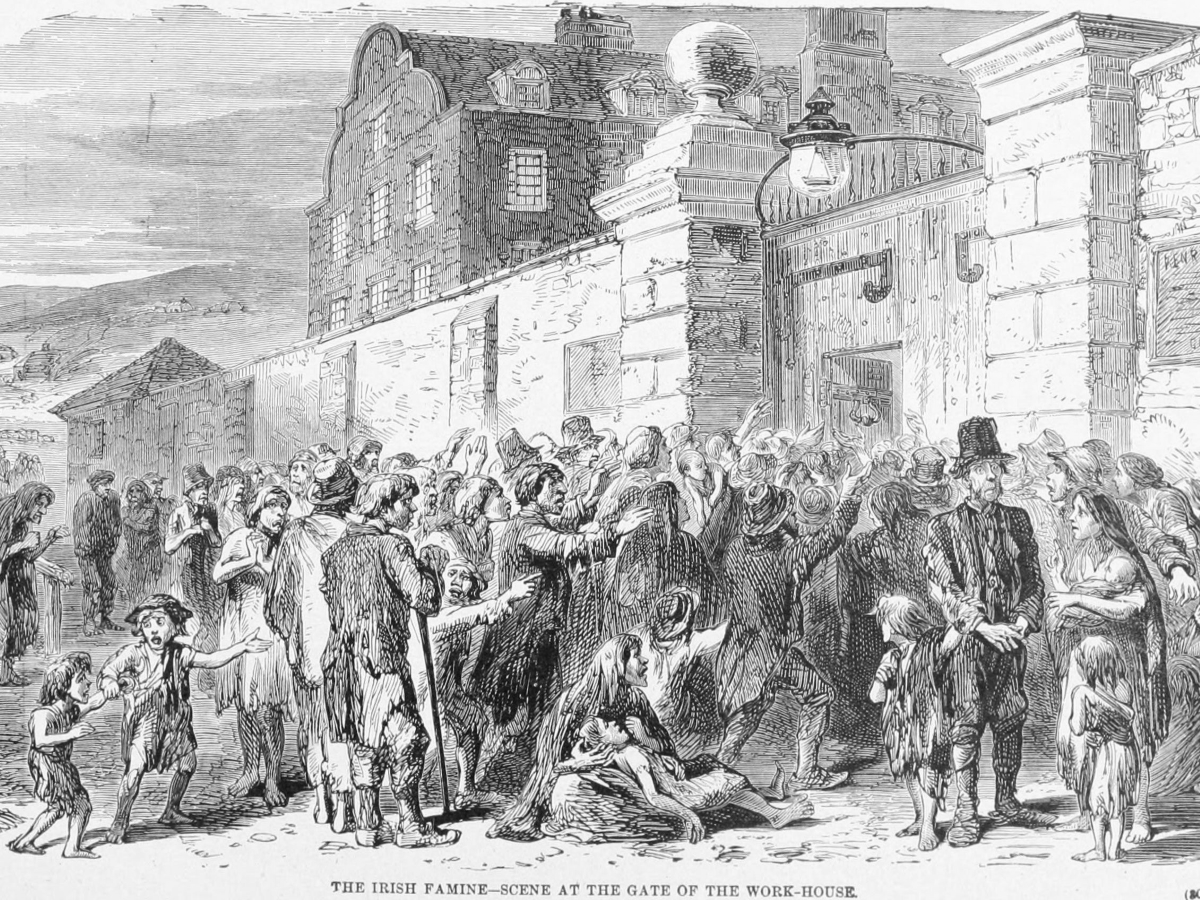

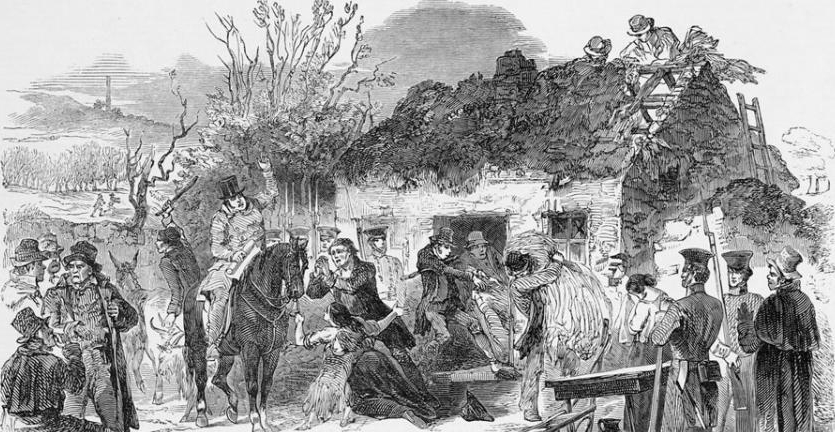

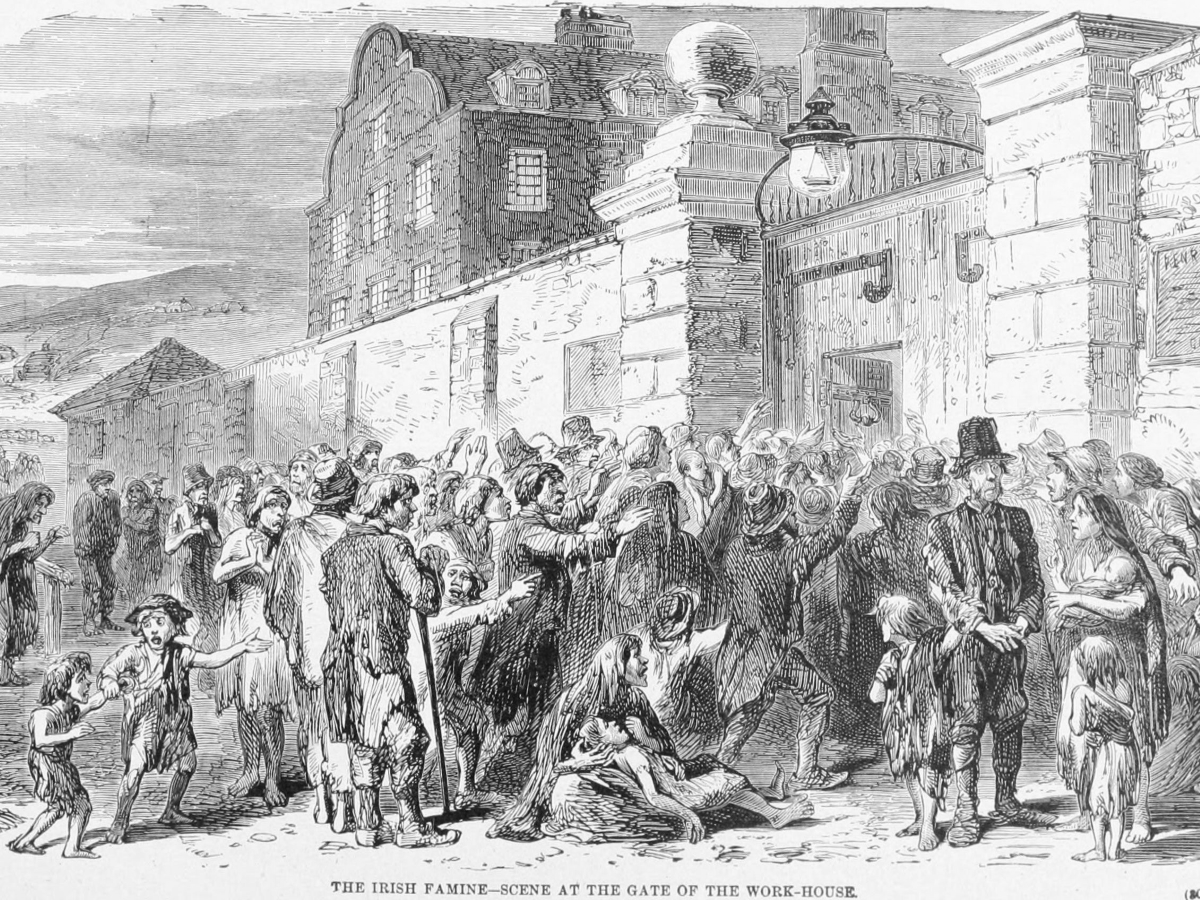

The Irish Question

One of the issues greeting Victoria and her advisors or cabinet in her

first years was the matter of the Irish. Ireland was fervently

Catholic ... England and Scotland equally fervently Protestant.

Over the centuries the Irish, used to tribal government, were brought

into English feudalism – where the land came under the ownership of

English lords, mostly absentee landlords who remained in England while

they collected taxes and services from the Irish farmers ... offering

the Irish few (if any) benefits in return. The unfairness of all

this hit hard in the 1840s when a rapidly expanding Irish population –

which lived mostly off a diet of potatoes ... found themselves facing

starvation when a potato blight in 1845 destroyed the all-important

Irish potato crop. The Irish could have somehow survived the

worst of the crisis ... except that 1) the Corn Laws (grain laws)

passed in 1815 to protect English farming essentially made the import

of foreign grain virtually impossible and 2) Ireland still produced

enough food (grain, sheep, cattle, etc.) to have fed (meagerly) the

Irish population ... except that English landlords sold the Irish

production to foreign purchasers.

The plight of the Irish caused parliament finally to repeal the Corn

Laws the next year (1846) ... except the blight again destroyed the

potato crop. Food was brought in from India ... though too little

to hold off the starvation of Irish, which was now reaching major

proportions. Then in 1847 – and again in 1848 and 1849 – the

blight continued. And so did the starvation ... which given the

weakened condition of the Irish was now joined by the plague. In

those five years over 700,000 Irish died. And an equally

huge number escaped death only by emigrating (many to America).

Consequently, the crisis left a deep bitterness among the Irish towards

their English masters. Secret societies formed with a goal

similar to the ones on the European continent: national

independence.

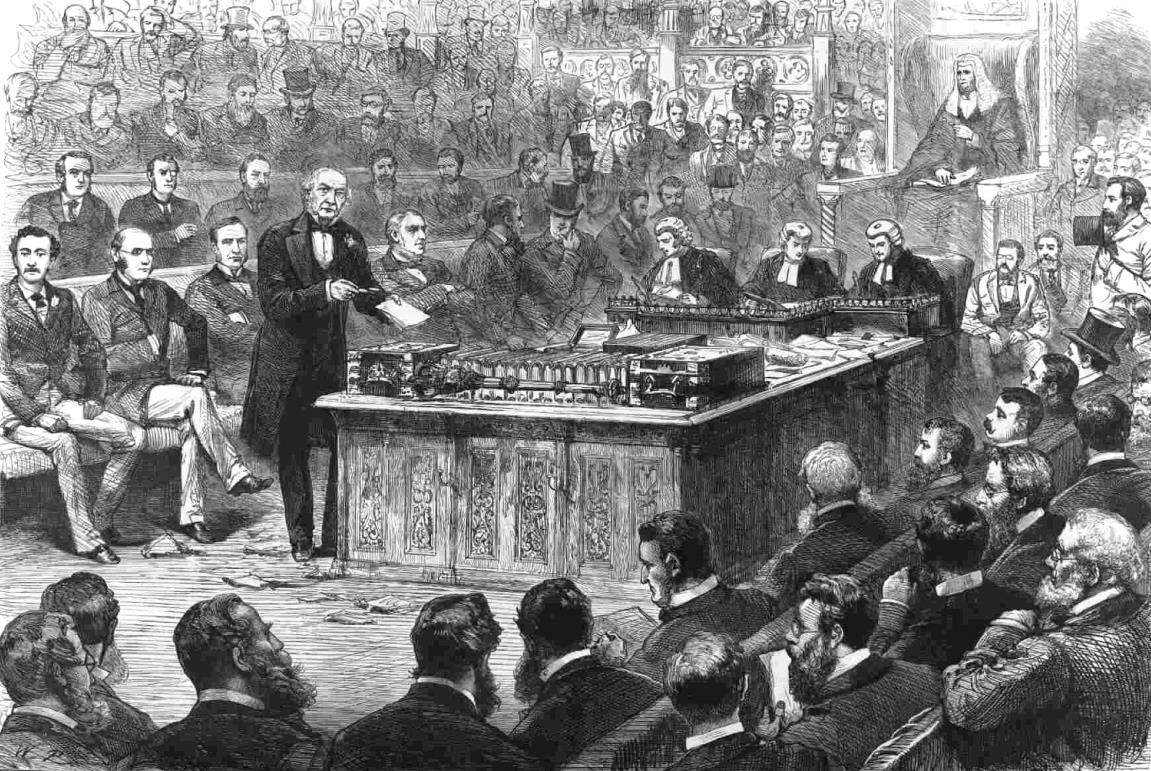

It was not until Gladstone took office as British prime minister in

1868 that a serious effort was made to address the Irish

question. Gladstone pushed through an act disestablishing the

Anglican (Protestant) Church in Ireland, undertook land reform offering

greater opportunity for secure Irish ownership of their lands and

promising fairer rent payments. Sadly, English landlords would

often ignore these reforms. Thus over time a "Home Rule" movement

gathered momentum in Ireland ... demanding Irish self-rule in all

matters except foreign or imperial policy abroad. But efforts of

Gladstone in 1886 and 1893 to push such a policy through parliament

were both met by defeat. Thus as the 20th century approached, the

political situation in Ireland was becoming explosive.

|

The Irish Question

Destitute Irish peasants being evicted from their homes

|

British democratic reform

It is important to note that Great Britain does not have some

great single document called a constitution, such as America has

possessed since 1787 and political reformers on the European continent

sought to put in place since the late 1700s. According to

constitutional theory in Great Britain, any act of Parliament has

constitutional authority. Thus when we talk of reform or

development of the British Constitution we are simply describing the

history of the various acts of Parliament that have shaped British

political society. Actually and most importantly, when the

British talk of their constitution they are describing not even just a

series of laws passed by Parliament but a larger moral-ethical sense

that underlies all British politics. It is this larger

moral-ethical sense by which they are "constituted" politically.

The Reform Act of 1832 had cleared up much of the political corruption

of the "rotten boroughs"3 generated by strong demographic changes in a

rapidly industrializing Britain and had brought an expansion in the

number of citizens entitled to vote. But that expansion reached

only to the level of the middle classes ... ignoring the right of

political participation of the even more rapidly expanding population

of the British rural and urban industrial working class. At first

the Chartist movement of the 1840s attempted to bring reforms to a more

fully democratic basis. But its seeming connection with the

continental events of 1848 merely brought stiff resistance to the

movement and it soon died away. But the Tory or Conservative

Prime Minister Disraeli took up the cause in 1867 ... just after the

Liberal Gladstone had succeeded the previous year in pushing through

the House of Commons a very weak reform measure. Disraeli’s

Reform Bill extended the vote to all householders and long-term renters

(except that it still exempted most miners and migratory farm workers).

Actually it was the Liberals who first benefitted from this expansion

of the electorate. With a majority in the House of Commons in

1868, Gladstone was able to begin to push through a series of pieces of

legislation providing for the secret rather than the oral ballot, the

expansion of national education (doubling the number of local schools),

and the reform of both the civil service and the military (appointment

by exam or proven merit ... not just personal connections!). Then

in 1874 a national election returned Disraeli and the Conservatives to

power ... and Disraeli continued the reform movement, focusing more on

the working conditions and hours of the British working classes.

In 1880 the national vote turned again in Gladstone’s favor, and he was

able in 1884 to extend the vote to the agricultural laborer. And

the next year his Liberal majority passed an act redesigning the

individual constituencies so that they represented more equitably the

spread of the British population. And thus it was that by the end

of the century Great Britain could claim to be truly a constitutional

democracy.

3A

district sending someone as a representative to Parliament … except

that the district demographically represents very few actual voters –

often only a particular individual or family.

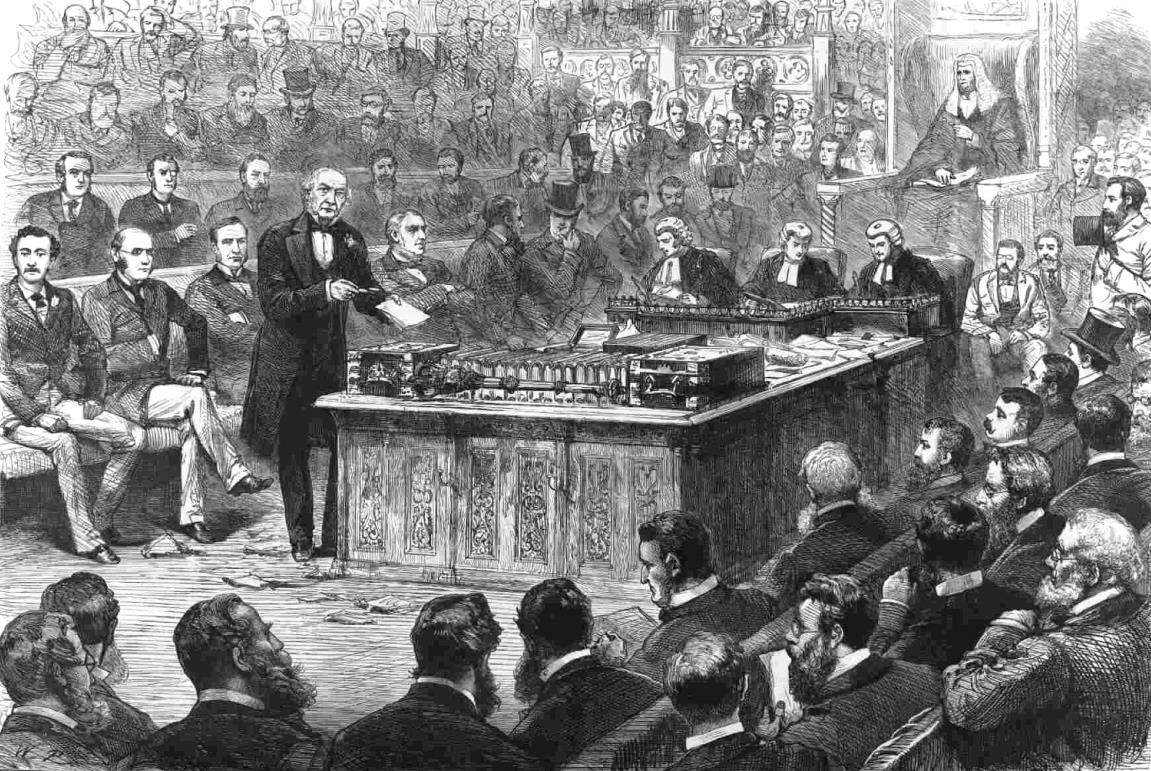

Disraeli introduces his Representation of the People Act in Parliament - 1867

Gladstone introducing political reforms for Ireland - 1886

|

Autocracy

The word "autocrat" had originally been merely a Greek or Byzantine

title for "emperor."4 It conveyed pretty much the same political

sense that "divine rights" did among West Europe’s kings. Thus

the Russian Tsar proudly pronounced himself to be the Russian

Autocrat. But it was the actual behavior of the tsars over time

that gradually made "autocrat" to mean "despot" or even "cruel

dictator," someone possessing unquestioned or total power over his

people.

This had not always been the case. The build-up of Tsarist power

in Russia occurred in tandem with the development of the rise of

monarchical power to the west in Europe ... except that unlike Western

kingdoms, there were no other institutions such as the church or the

aristocracy offering some kind of check, even though small, on the

powers of the king. In Russia (as in England), the church did not

have a political base outside the reach of the tsar, and the tsar thus

controlled the personnel and activities of the church ... which existed

mostly to bring the Russian people to faithful support of the

autocratic tsar. Russia did have a small class of noblemen but

they had no independent power, the tsar being able to appoint them ...

but also depose them, not only from his imperial service but from even

their lands and titles. There existed few towns and thus hardly

anything constituting a Russian middle class.

Serfdom

The economy of Russia was nearly entirely agricultural, with all but 5

per cent of the population making up the peasant class. And even

this huge class had its earlier rights completely taken from it over

the course of the 1600s and 1700s – as the farmers were increasingly

restricted in their ability to move about in the quest for better

working conditions, being locked into place by law under landlords

given increasingly absolute control over their lives. Thus

gradually step by step they were turned into the semi-slave category of

"serf" ... at a time when West Europe was moving in the opposite

direction, gradually freeing up their serfs and recasting them as free

(peasant) farmers.

But the Napoleonic wars made very clear the dangers to Russia created

by this archaic social system. There was no question of loyalty

of the serfs to their tsar, Alexander I ... though their attitudes to their landlord

noblemen was a different matter (revolts were frequent). They

worshiped the tsar. But the tsar needed more than worship.

He needed a society with a strong industrial economy and a national

army of some modern (i.e., educated) sophistication. He had

neither.

Nicholas I (1825-1855)

Alexander died suddenly in late 1825, just as the spirit of military

revolt was gathering momentum. His younger brother Constantine

had no desire to become tsar and stepped aside for the even younger

brother Nicholas ... upsetting the reformist soldiers who went into

full revolt in December at the news, thus the "Decembrist

Revolt." Nicholas crushed the Decemberists, setting the stage for

the rest of his repressive reign. One of the goals of the

Decembrists had been the ending of serfdom ... consequently making the

reform of serfdom one of the main objects of Nicholas’ wrath for the

duration of his reign. Constantly fearing reformist movements, he

tightened censorship of the press ... and cut back on national

education at both the local and university level, driving Russia even

deeper into intellectual darkness.

Alexander died suddenly in late 1825, just as the spirit of military

revolt was gathering momentum. His younger brother Constantine

had no desire to become tsar and stepped aside for the even younger

brother Nicholas ... upsetting the reformist soldiers who went into

full revolt in December at the news, thus the "Decembrist

Revolt." Nicholas crushed the Decemberists, setting the stage for

the rest of his repressive reign. One of the goals of the

Decembrists had been the ending of serfdom ... consequently making the

reform of serfdom one of the main objects of Nicholas’ wrath for the

duration of his reign. Constantly fearing reformist movements, he

tightened censorship of the press ... and cut back on national

education at both the local and university level, driving Russia even

deeper into intellectual darkness.

The backwardness of Russia finally registered itself fully during the

Crimean War ... when it seemed that all of Europe was lined up against

Nicholas. In short order not only did his huge military apparatus

disintegrate but his civil government itself seemed to collapse in

corruption. In the midst of the conflict he died of pneumonia ...

though there were rumors of suicide.

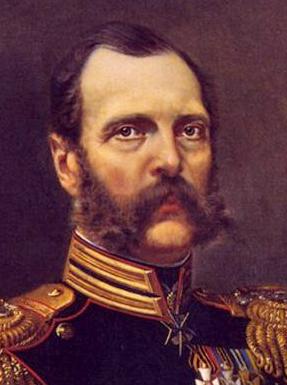

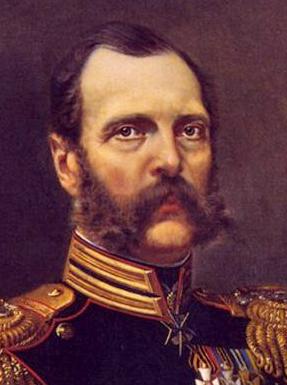

Alexander II (1855-1881)

Nicholas’s son Alexander II quickly reversed course and headed Russia

down the path of reform in order to bring the country into the modern

era. In 1861 he authorized the emancipation of the serfs, then

moved to give Russia a more systematic legal system and a new judicial

system to supervise it, encouraged local self-government with his

zemstvo system, brought educational reform back into play ... and

instituted universal military training and service. His goal was

completely pragmatic, the strengthening of the social foundations of

Russia in the new modern era, and not particularly idealistic, for he

proved to be just as repressive as his forebears when it came to

organized attempts to oppose his rule. Indeed, when Polish

patriots rose up in 1863 against Russian rule, Alexander responded by

ending Poland’s separate status (Alexander was Polish king as well as

Russian tsar) and simply incorporated the Polish territory into

Russia. Nonetheless, he was still at work trying to reform

Russian politics in order to make it acceptable to reformist interests

when he was assassinated (1881).

Nicholas’s son Alexander II quickly reversed course and headed Russia

down the path of reform in order to bring the country into the modern

era. In 1861 he authorized the emancipation of the serfs, then

moved to give Russia a more systematic legal system and a new judicial

system to supervise it, encouraged local self-government with his

zemstvo system, brought educational reform back into play ... and

instituted universal military training and service. His goal was

completely pragmatic, the strengthening of the social foundations of

Russia in the new modern era, and not particularly idealistic, for he

proved to be just as repressive as his forebears when it came to

organized attempts to oppose his rule. Indeed, when Polish

patriots rose up in 1863 against Russian rule, Alexander responded by

ending Poland’s separate status (Alexander was Polish king as well as

Russian tsar) and simply incorporated the Polish territory into

Russia. Nonetheless, he was still at work trying to reform

Russian politics in order to make it acceptable to reformist interests

when he was assassinated (1881).

4From

the Greek – αuτόu (auto) meaning "self" and κράτωρ (krator) meaning

"ruler" or "governor" – someone given the power to make political

decisions independently or by his own authority.

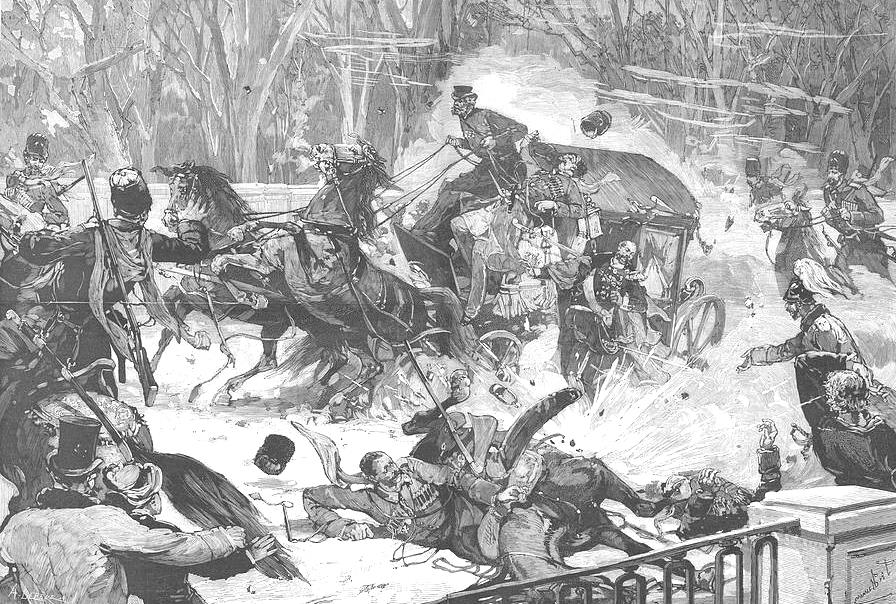

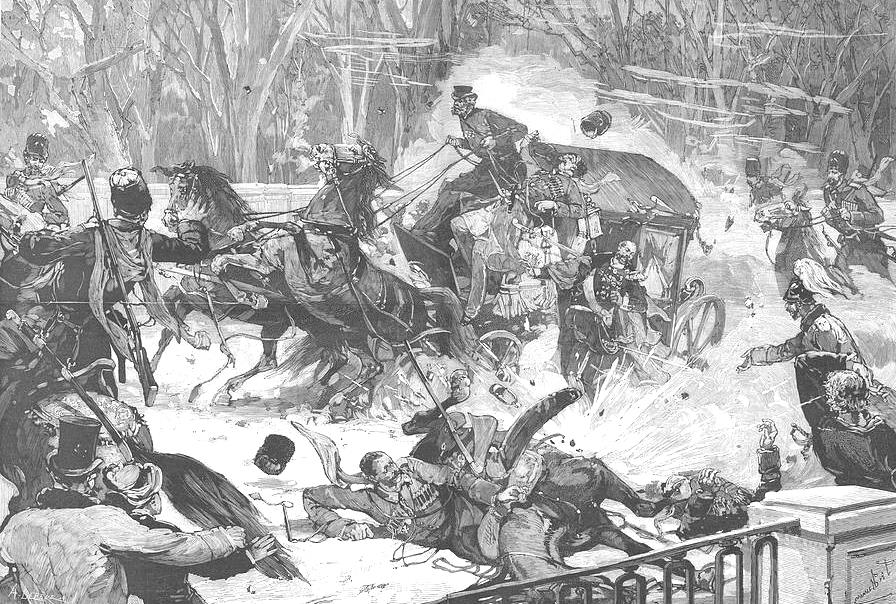

After numerous attempts on his life, the nihilist Norodnaya Volya ("People's Will) assassins succeeded in bombing Alexander's imperial train ... in the hopes of starting a revolution.

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR ...

BUT SUBSEQUENT RISE TO INDUSTRIAL GREATNESS |

|

The

issue of slavery

At the time of the creation of the American

Constitution, the issue of slavery and how slaves were to count in

deciding representation in the House of Representatives had put a

strain on the relations among the new states, divided on this issue

within the new union largely on a north-south basis. Southern

culture with its semi-feudal instincts had come to depend heavily on

slave labor ... but knew somehow it was morally wrong. Optimists

claimed that it would simply wither away by itself as an institution

over time. Some went so far as simply to free their slaves ...

usually as part of their will at death (Washington, for instance;

however, because of his huge debts, Jefferson did not). Indeed,

one of the last acts of the wartime Continental Congress before it

turned power over to the new Federal Congress in 1789 was to designate

the territories northwest of the Ohio River over to the French colonial

border along the Mississippi River to be forever free of slavery.

But the acquiring of new lands beyond the Mississippi with the

Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803 stirred the slavery issue to new

life. Southerners, whose cotton farming had exhausted the land,

were as interested in the territory west of the Mississippi as were the

northern farmers. Southerners fought to keep the new territories

open to slavery ... and won the idea in principle with the Missouri

Compromise of 1820. Entrance of new territories into the Union as

full states would occur in such a way that for every "free" state

brought in, the South would be entitled to enter a "slave" state ...

thus keeping a balance in numbers of free and slave states in the

Senate.

At this point the issue for Southerners was no longer a question of

when slavery might be ended (as it had elsewhere in the Western world)

but how it might be protected ... and even be justified morally.

Biblical testimony at this point was brought in to prove that somehow

slavery was even part of God’s intentions. The North of course

was horrified at this misuse of holy scripture. Thus a deep moral

divide, as well as an economic lifestyle divide, deepened further a

growing political-cultural split separating the North and the South.

Bleeding Kansas

In 1854 the decision to split the Nebraska

territory into two states, Nebraska in the North and Kansas in the

South, brought the issue to the boiling point. Nebraska would

clearly become a free state. But the idea of then making Kansas a

slave state brought such an angry reaction from Northerners that the

decision was made to let the people of Kansas decide their status

themselves. This was the signal of both sides to send masses of

settlers to Kansas to weigh the outcome in their favor ... producing in

Kansas itself a scene of bloody violence between armed defenders of one

group of settlers against the other. Soon the entire country was caught

up emotionally over this bitter issue.

|

A slave auction in Charleston

Pro-slavery "Border Ruffians" executing "Free State" (anti-slavery) Kansans - May 1858

|

The Lincoln-Douglas debates (1858)

The

nation watched closely the debates in Illinois between Abraham Lincoln

and Stephen Douglas as they competed for a U.S. Senate seat. The

leading U.S. Senator of the day, Douglas, pressed for tolerance on the

slavery issue; the rising Lincoln was certain that slavery would

destroy the Union if it were not abolished. Douglas won the

election ... but Lincoln won the heart of the new Republican Party ...

which two years later nominated him for the presidential race.

|

|

Lincoln ... the man

Lincoln was vastly more the man than his Republican Party opponents (at

first) believed him to be – supposing him to be just some kind of

"country boy." Thankfully for America, Lincoln was a truly great

leader, understanding deeply the importance of long-term grand strategy

– when the political world around him could think only in terms of

immediate tactics.

Lincoln was vastly more the man than his Republican Party opponents (at

first) believed him to be – supposing him to be just some kind of

"country boy." Thankfully for America, Lincoln was a truly great

leader, understanding deeply the importance of long-term grand strategy

– when the political world around him could think only in terms of

immediate tactics.

Previous presidents had merely kicked down the road the can of the

increasingly divisive slavery issue ... for those that came after them

to deal with. The political cost of bringing the matter to a

solution was just something previous presidents could not stomach. But

Lincoln knew God had called him to bring this horrible issue to full

resolution ... if the God-ordained Union (which Lincoln talked about

frequently) were to be saved.

Indeed, he drew closer and closer to God as the contest dragged on,

depending on God's counsel – and most frequently, God's counsel alone –

in directing what was becoming the bloodiest contest that the country

had ever seen (or seen even since then!).

Tragically, not achieving immediate success in their efforts to bring

matters to a resolution, the will of those around him (including his

wife) to press forward in the face of this challenge faltered

badly. Why not just give it up ... and let the South go its way?

The war itself (1861-1865).

The war was dragging on year after year, with Lincoln changing

commanding generals one after the other because of their rather

unexceptional service. Consequently, the North was tiring of the war

... and it took the incredible will of Lincoln not to call it quits and

simply let the South slip away.

Very sadly for the multitudes who died or were gravely wounded in

military service – with little to show for their supreme sacrifice – it

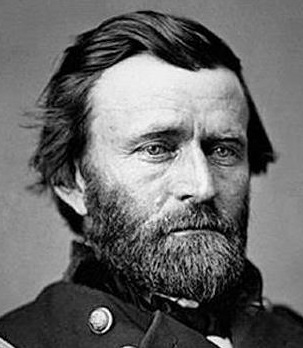

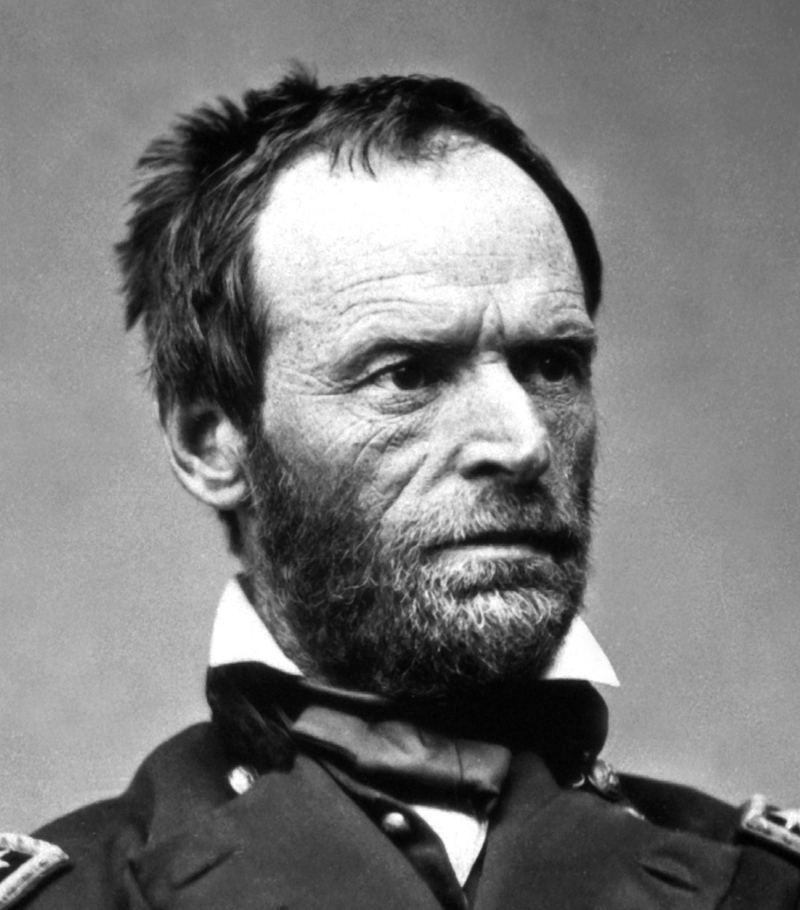

took Lincoln over two years to find military leaders (Ulysses S. Grant

and William Tecumseh Sherman) who understood that wars are not won by

great battles ... but only by the wearing down of the enemy's resolve

to continue. And that, not just a grand battle here and there, would

take many battles – and very unpleasant measures – to bring to actual

victory.

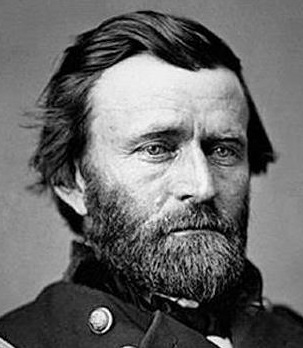

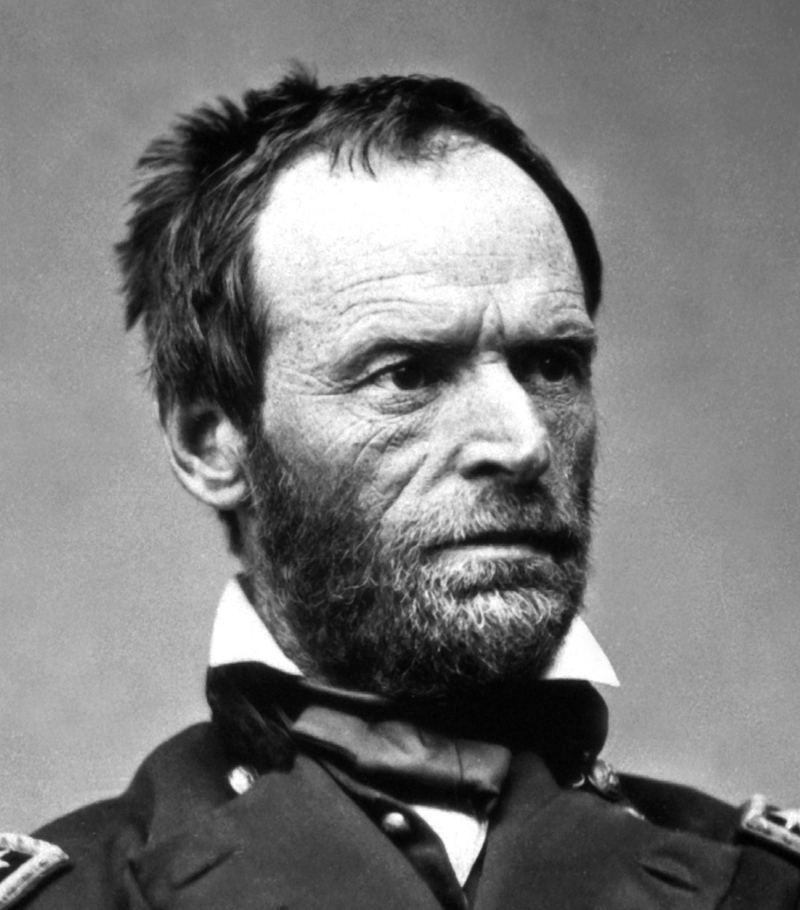

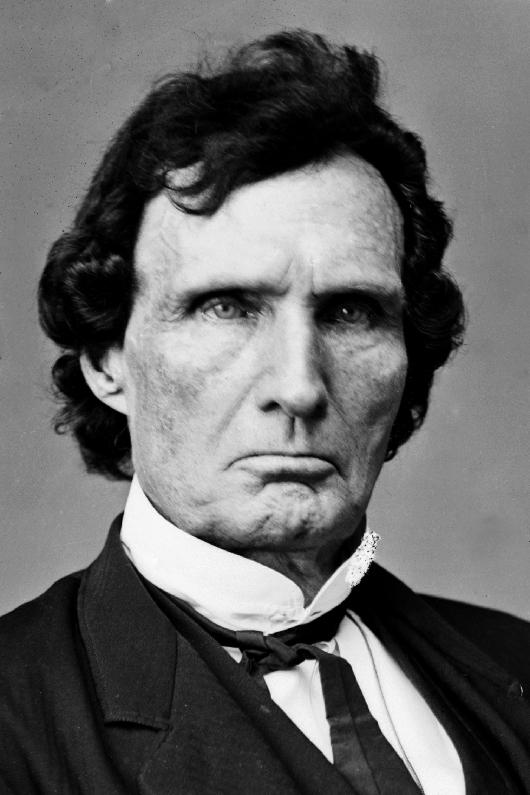

Ulysses S. Grant

William Tecumseh Sherman

The

war was largely a defensive one for the South, more easily

understandable and thus easier to conduct ... thus defensive except in

the one instance when Southern General Robert E. Lee invaded the North

– but was soundly defeated at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1963) in

Pennsylvania. This Northern victory certainly picked up the

wearied spirit of the North ... though not greatly.

"Victory" was not yet in the picture ... until General Grant took over

the Northern forces. At this point Lee discovered that he was up

against an opponent who, though not a brilliant tactician, was a

relentless bulldog that was determined to push the South relentlessly

... to the point of exhaustion. And that point came at Appomattox

in April of 1865. The South finally had to bow in total

defeat. The Union was saved ... and the issue of slavery was

finally resolved. |

|

Lincoln's famous 2nd Inaugural Address (1865)

With that victory in the making, Lincoln was faced with the challenge

of putting the Union back together as a truly unified community ...

bringing former slaves into the full responsibilities of citizenship,

and re-integrating into the community those who had fought so hard to

preserve that slavery. Lincoln – and the country – would need

God's help ... as Lincoln made very clear in his new inaugural address,

issued in taking up his second term as U.S. president.

It is well worth quoting ... for he stated very clearly the

moral-spiritual challenge facing the nation – the likes of which has

not been heard from an American presidential leader ever since ... for

it was very much more than just a fine speech. It was a sermon to

a hurting nation:

...

Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration,

which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause

of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself

should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result

less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and

pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.

It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's

assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces;

but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both

could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The

Almighty has His own purposes.

He then explained that slavery was one of those offenses against God

that God would allow – but only until such time as he was ready to

exact his judgment, through the terrible war they had been

experiencing.

If

we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which,

in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued

through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives

to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by

whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from

those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always

ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope – fervently do we pray – that

this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God

wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond man's

two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until

every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn

with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must

be said the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.

He concluded:

With

malice toward none; with charity for all; with a firmness in the right,

as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work

we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall

have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan – to do all

which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among

ourselves, and with all nations.

Lincoln is assassinated

Then tragically, Lincoln was shot and killed only a couple of weeks

later by a Southerner who thought he was doing the defeated South a

great favor in taking down their primary adversary. With that

bullet, any thought of a much-needed cultural-moral reconciliation

between the North and the South disappeared.

Equally tragically (for both North and South), those that came after

Lincoln had neither the moral courage nor the political leverage to

move the country forward to Lincoln's plan for restored national

unity. Instead, Congress's Radical Republicans undertook

self-righteous measures designed to keep former Confederates powerless,

measures which merely drove the country more deeply into a

political-moral standoff. This would do neither North nor South

any good.

For more on The American Civil War For more on The American Civil War

|

Union artillery at the Battle of Yorktown -1862

Union troops prior to the third battle with the Confederates at Fredericksburg - 1863

Confederate dead at Mary's Heights overlooking Fredericksburg - 1863

|

Efforts to impeach the new president

In accordance with this new moral self-appointment of the Radicals,

impeachment charges were leveled at President Andrew Johnson (the

former vice president) in an effort to remove him from power … because

he was considered too soft on the South – when he tried to follow

Lincoln's efforts to reunite politically the South with the North,

rather than punish the South.

The use of the impeachment instrument was designed for very

exceptional circumstances (a president actually committing a serious

federal crime) rather than just for political purposes. This was

its first use … though hardly over a criminal matter. This was

simply very bad political morality in action. Thankfully, the

effort to chase Johnson from office would fall just short of the

necessary two-thirds vote of the Senate. But it would leave

Johnson powerless as president thereafter.

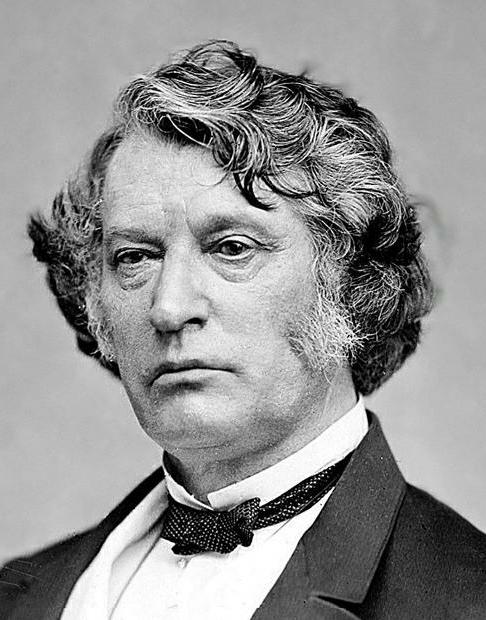

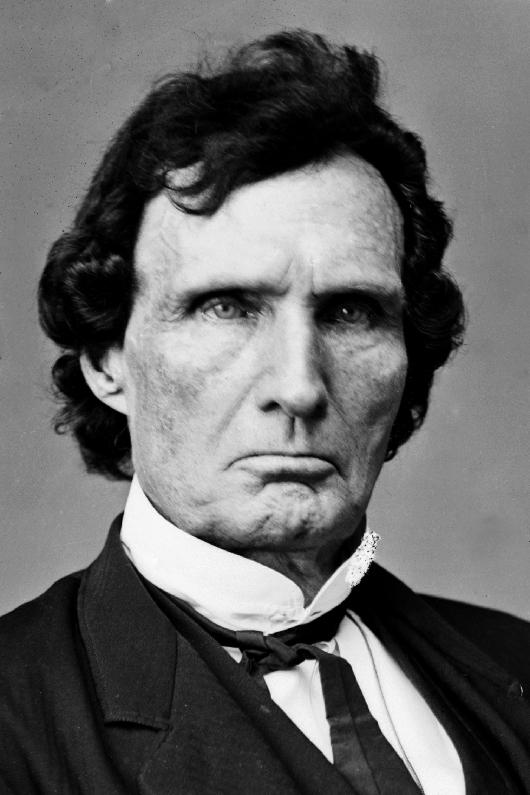

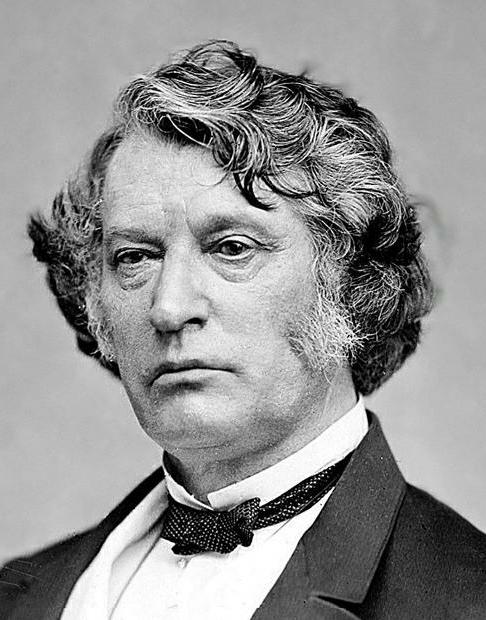

Leaders of the Radical Republicans, Thaddeus

Stevens (above) and Charles Sumner (below) ... who led the anti-Johnson impeachment efforts

This

powerful political tool would not be put to use again until a century

later (the effort to drive Nixon from the White House) … and then –

most tragically – would become part of Congress's political weaponry

used quite frequently by the president's political opposition in

Congress … a sign of the moral decline of Washington politics.

But more about that later!

But peace weakened the resolve of

the North to press the South to implement full equality for all of its

citizens, Black as well as Whites. And in subtle ways the South

found ways of putting Southern Blacks under complete political,

economic and cultural restraint ... leaving a huge social problem yet

unresolved.

The after-effects of the war

However,

peace ultimately weakened the resolve of the North to continue to press

the South to implement full equality for all of its citizens, Black and

White. And in subtle ways the South gradually found ways of

putting Southern Blacks back under complete political, economic and

cultural restraint ... leaving a huge social problem yet unresolved.

But at this point, the North was busy with its attention focused

elsewhere, opening more lands for settlement along the Western frontier

and continuing the rapid development in the East of the American

industrialization that the war had promoted heavily. The South

meanwhile sunk back into its semi-feudal ways, with the old families

still dominating life from behind the political scenes and with a

resentful population of poor Whites determined to keep Southern Blacks

fully oppressed. Thus the opportunity produced by the Civil War

to bring the South into harmony with Northern democratic and

egalitarian ideals was lost ... for a full century.

But the social scene in the North was not all that serene either.

The frontier with the Indians was closing … and there was no more good,

cheap land for the expanding Anglo population to move to. The

squeeze was on for younger sons to find a way to make their own

fortunes … with most of them having to move to the urban-industrial

East to find employment in the mines and manufacturing plants, where

salaries barely covered life’s most basic expenses. This occurred

at the same time that multitudes of immigrants were leaving Europe

behind to come to America in the search for the same manufacturing and

mining jobs. Anglo America balked at how this was changing the

country from a largely rural nation to one where urban life was fast

taking the social lead ... and with all sorts of inhabitants (and

corrupt political bosses and urban governments) that made urban America

feel "foreign."

|

|

America’s rise as an industrial giant

But this was also

indicative of the deep changes going on within the American

economy. America continued to possessive vast wealth in its

extensive farmlands and its multitude of small rural towns. And

America’s huge railroad and shipping infrastructure made for an

extremely efficient and powerful market for agricultural goods.

But its cities were also amassing great wealth as they turned to the

manufacture of a vast array of new machines that greatly energized the

American economy … and the mining of iron, coal and even oil to answer

the voracious appetites for raw materials of these mammoth

manufacturing operations. Indeed, so great was the industrial

growth of America during this time that by 1914 and the outbreak of the

European ‘Great War’ (World War One), America alone produced one-third

of the world’s total industrial wealth … more than Britain, Germany and

France combined.

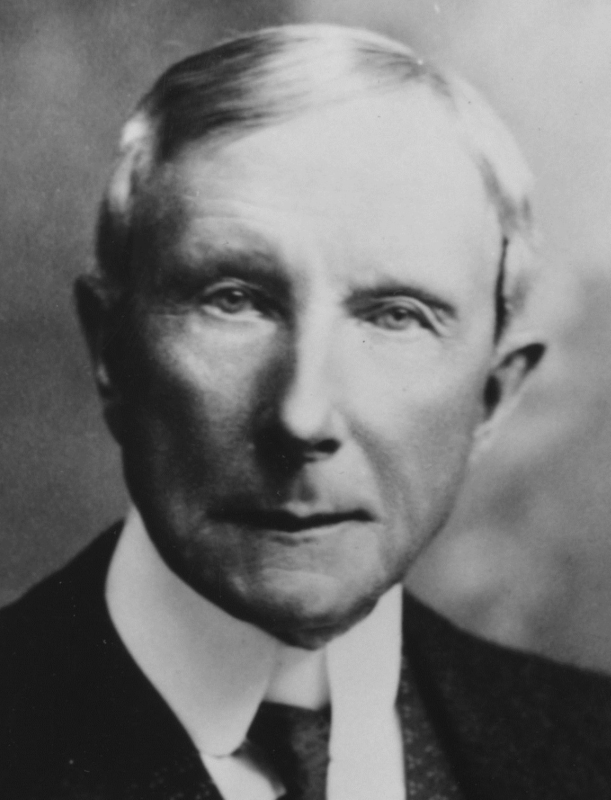

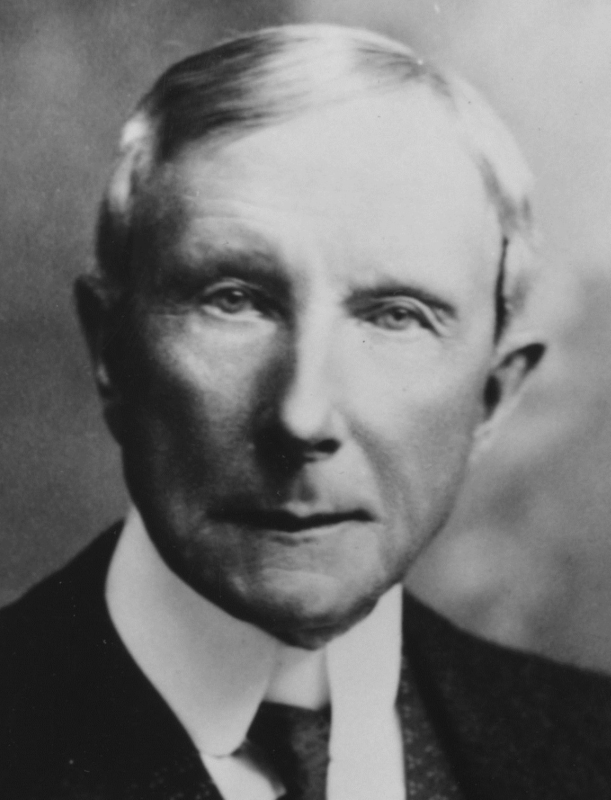

The "captains" (some would say "robber barons") of American

industry

Behind this growth was not a government (as in Europe,

mostly) but a small group of powerful individual capitalists, who

developed the ability to gather vast sums of money to undertake

industrial investment a massive scale.

Cornelius Vanderbilt grew

a business from a small ferry service (from New Jersey to New York

City) by the mid-1800s to a massive steamship corporation … and then

combining a number of railroad companies operating into the New York

Central Railroad.5 Competing with him in

the 1870s were Jay Gould and James Fisk … attempting a similar hold

over much of the East’s railroad business.

Then there was Andrew

Carnegie who came from Scotland to America in 1848 as a youth, taking