12. GLORY

THE LAST DAYS OF THE GILDED AGE

ITALY

CONTENTS

Problems with unity Problems with unity

Italy and the Catholic Church Italy and the Catholic Church

Social problems Social problems

The monarchy The monarchy

Italian imperialism Italian imperialism

Italy ... around the year 1900 Italy ... around the year 1900

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 52-55.

Italy

was finding that as difficult it had been to create Italy, it was

proving to be even harder to create Italians. Most Italians saw

themselves as Venetians, Genoese, Florentines, Sienese, Romans,

Neapolitans, Sicilians, etc. well before they recognized themselves as

Italians. These local identities had been at the heart of their

economic competitions and wars for countless generations ... and it was

very hard for them to rise above those local loyalties to take on the

primary identity as Italian. Part of the problem also was that

those who had supported the Risorgimento had been mostly a relatively

small group of urban upper-class intellectuals ... and not really the

vast peasant population who simply watched the unfolding of events and

the creation of Italy from the sidelines. Most Italians had not

themselves invested much in the creation of the new Italian

state.

Also, now that the young political idealists had achieved the dream of

a united Italy wrested from the hands of surrounding powers, they had

no similar national challenges still facing them, ones that could

continue to draw them together in a spirit of ongoing national

unity. The Risorgimento had achieved its goals ... and there was

no similar burning sense of what was supposed to happen next. |

TALY AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH |

| Also, Italy was a very Catholic

country ... and the hatred of the Church for the constitutional

monarchy that had taken away the Church’s vast landholdings made it

difficult for the devout Catholic Italians to love their new

government. The new Italian state was constantly denounced from

the local pulpits ... and particularly by Pope Pius IX (Pope:1846-1878)

who hated what had been done to the Church and considered himself a "prisoner of the Vatican."

|

Pope Pius IX and a number of Cardinals

|

Poverty

Italy was a poor country, with a high mountain range

running north and south through the middle of the country.

Industry was still in its infant stages ... and agriculture was the

economic mainstay of the country ... though even here productivity was

very low. Much of the population lived near the starvation level

and disease was rampant. Nonetheless even in the face of these

problems, the rate of population growth was extremely high ... pinching

Italy even more. As a result, sadly one of Italy’s major

“exports” was its population, which went abroad in the hopes of finding

a better life elsewhere. Expatriates did indeed help finance life

in Italy, sending money back home to their families. Many would

also return to retire in their homeland where their savings would carry

them further in life.

Illiteracy

Literacy was very low, especially in the south where

even as late as 1870 only about one tenth of the population could read

and write. Even in the somewhat more prosperous north hardly half

of the population could read and write at that time. But efforts

to improve Italian education in the early years of the twentieth

century would begin to have an impact on this problem... though even as

late as 1914 over a third of the population was still illiterate.

Political corruption

Italian politicians tended to look only to

their own political careers ... not being vitally interested in issues

larger than their own personal success. Political parties were

numerous and actually only small groupings centered around key

individuals, the groupings held together by the favors these

individuals drew from their political office and were able to pass on

to their personal following. This in turn produced terrible political

instability as governments in Rome rose and fell simply on the basis of

personal politics.

Taxes were very heavy on the tightly stretched Italian population ...

and governments were not inclined to keep expenses in line with Italy’s

actual ability to afford the projects produced by the government.

Thus for many Italians, the state seemed to be no less an oppressor

than had been the earlier governments, whether local or foreign.

In the south of Italy people continued to look to the local Mafia

organization to supervise local life rather than to the distant Italian

government in Rome.

Real growth

And yet ... Italy did begin to register real growth

as the 1800s closed out and the twentieth century opened up.

Coming from so far behind economically it was of course easy to

register high rates of growth ... but in fact Italy was definitely

moving ahead in terms of industrial production (despite Italy’s own

lack of coal and iron deposits), railroad mileage, new port facilities,

drainage of swampland and improvement of agricultural yield.

|

Victor Emmanuel II, who had led the risorgimento to

its victory, died in 1878 ... not long into the life of the new

state. His place was taken by his son Umberto I, who reigned over

Italy until his death in 1900 when he was killed by an anarchist’s

bullet (he had escaped two previous assassination attempts). His

22-year reign however had been much less illustrious than that of his

father. Umberto was a very passive king who preferred to let the

politicians do the heavy lifting while he mostly watched from the

sidelines. Sadly he did little to pull Italy together as it slid

into a political lethargy that threatened even more the thin unity

holding the country together.

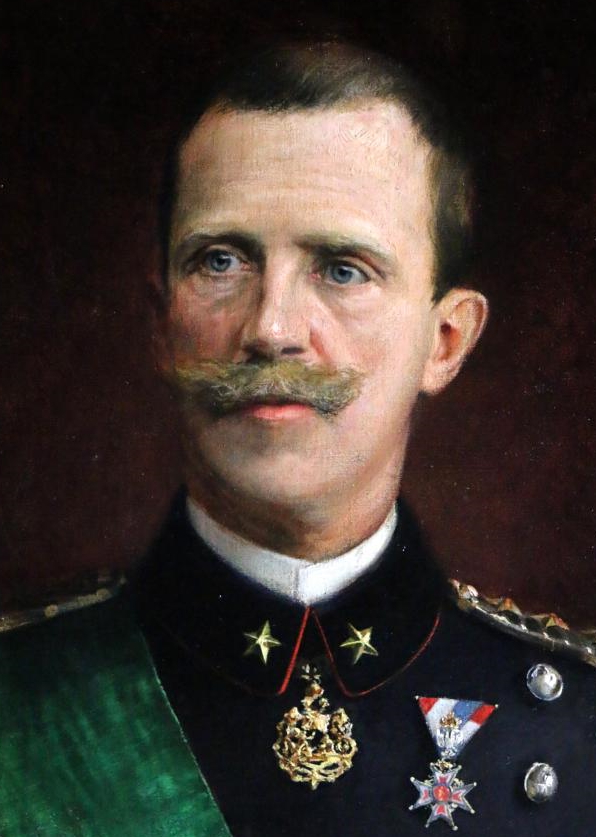

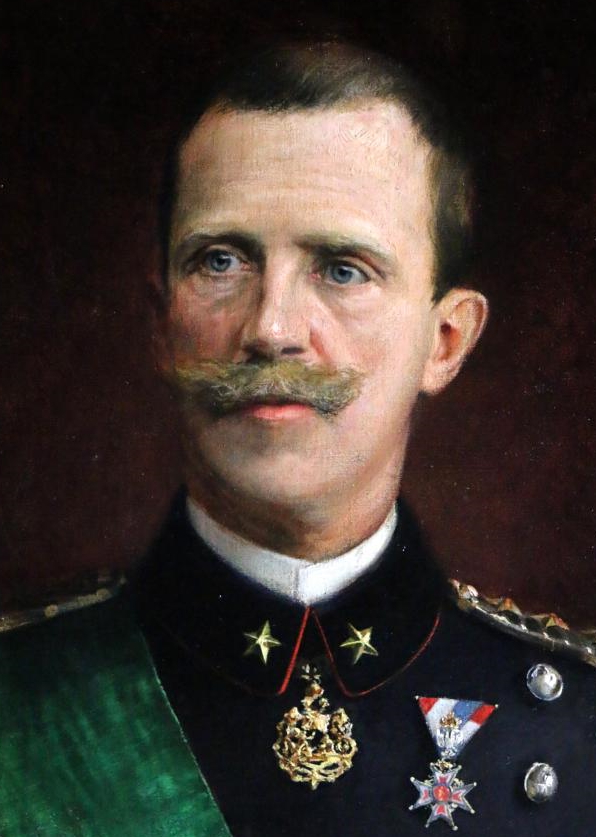

His place was taken by his son Victor Emmanuel

III (reigned 1900-1946). Despite the high hopes the country had

that this energetic young prince would be able to pull Italy back

together the passing of time proved that he really did not have the

strength to discipline the chaos of the various party bosses ...

including his prime minister Giolitti, who was in and out of office

five times in the period 1892-1921, and who also followed the political

trend of using his office simply for his own personal political good.

|

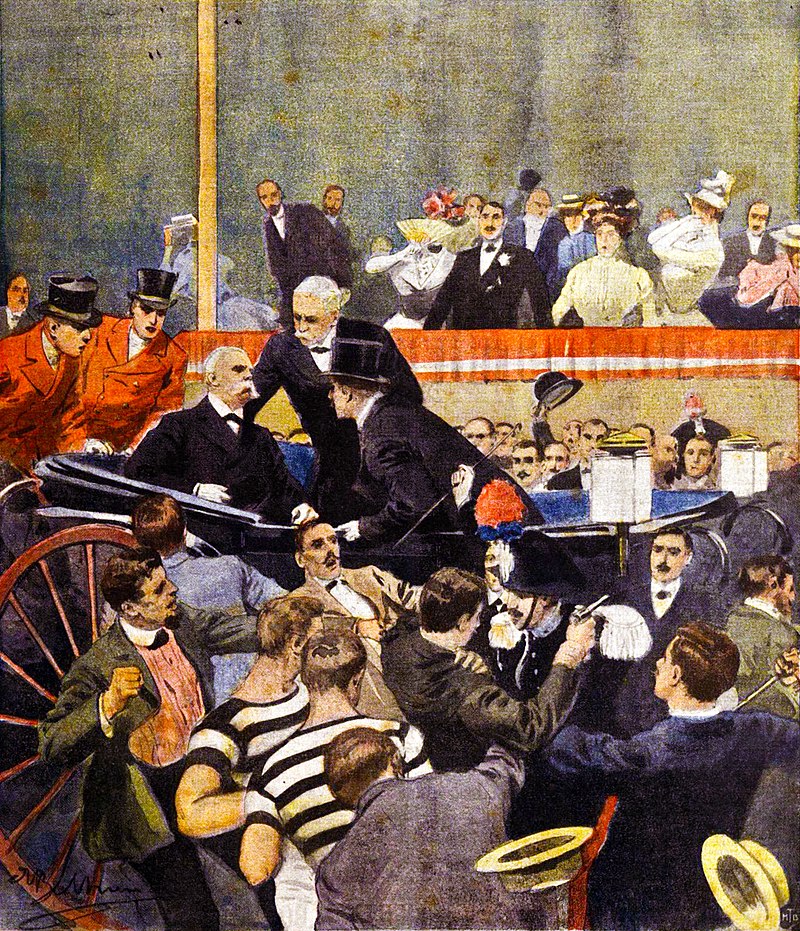

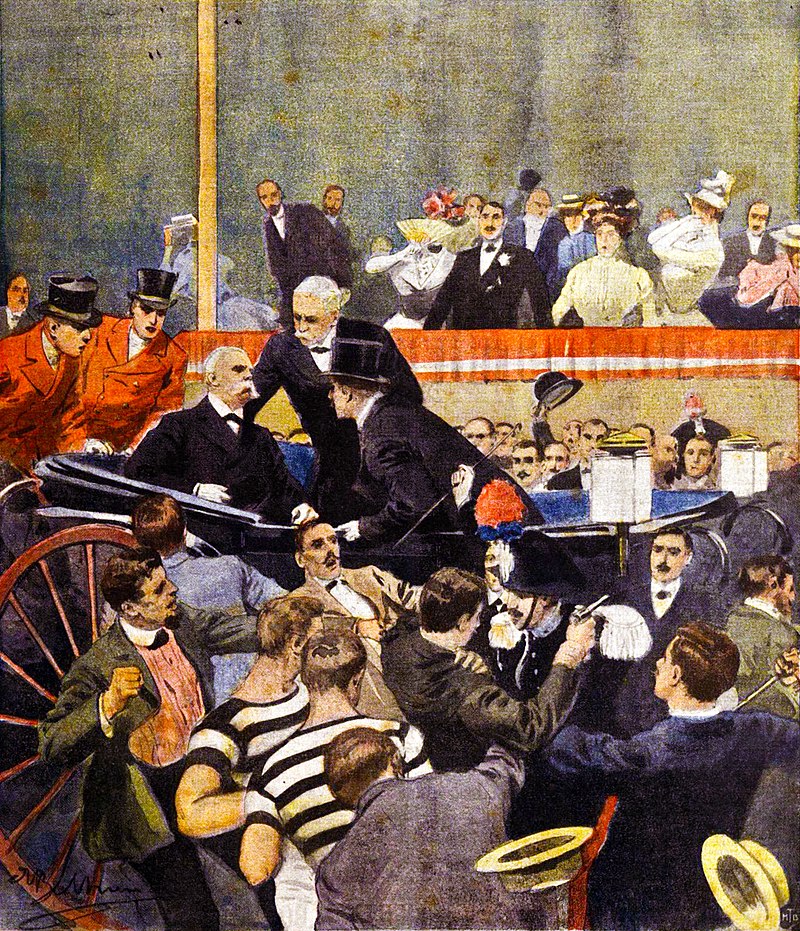

King Umberto is killed in Monza by Gaetano Bresci - July 29, 1900 - by Achille Beltrame

Victor Emanuel III (reigned 1900-1946)

Giovanni Giolitti - at the outset of his political career

One of the keys to successful

nationalism seemed at the time to be the securing of an overseas

empire. Thus Italian nationalists put in place an imperial

strategy ... but found the pickings overseas for Italian colonial

territory to be quite slim. Most of the prime territory in Asia

and Africa had been grabbed. This left only the sandy wastes of

North Africa and the horn of East Africa available for seizure.

The Italians were most desirous of Tunisia, just opposite the Italian

island of Sicily. But to the immense distress of Italy, the

French grabbed that territory in 1881 ... which by way of bitter

reaction drove Italy in 1882 to join with Germany and Austria-Hungary

in forming the Triple Alliance.

This would mark the beginning of diplomatic troubles that would not

only divide Europe into two contending camps ... but would ultimately

lead Europe into the "Great War" (World War One).

Things at this point did not get much better for Italy in the imperial

realm. An attempt to seize the Christian kingdom of Abyssinia

(Ethiopia) resulted only in the humiliating defeat of Italian troops in

1896 by local Ethiopian troops, ending that venture (for a while

anyway). Italy then moved its focus to the North African lands of

Tripolitania and Cyrenaica ... bombing from their new airplanes (the

Italians proved to be much better at aerial combat) Bedouin troops ...

and occupying in 1912 the few towns of a region they would unite and

then assign to this new piece of imperial territory the ancient Roman

name "Libya."

ITALY ... AROUND THE YEAR 1900 |

Venice - Piazza San Marco

A courtyard in Venice

Verona - Piazza delle Erbe

Rome - Via XX Septembre

Rome - Via Nazionale

Rome - "Great Palace"

Rome - Piazza Barberini

Naples - Via Roma

Naples

Go on to the next section: Spain

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| |

Problems with unity

Problems with unity

Italy ... around the year 1900

Italy ... around the year 1900