7. THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES

CULTURAL-INTELLECTUAL STIRRINGS

CULTURAL-INTELLECTUAL STIRRINGS

The huge intellectual debt owed to the

The huge intellectual debt owed to theworld of Islam

"Spiritual heresies" ... deviations from

"Spiritual heresies" ... deviations from

the official Roman-Christian order

Scholasticism ... and the restoration of

Scholasticism ... and the restoration of

"human reason"

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 251-267.

THE HUGE INTELLECTUAL DEBT OWED TO THE WORLD OF ISLAM |

| In

so many different ways, the West was on a major rebound during those

vital years of the 1100s and 1200s. While European commerce and

trade began to revive, so did the realm of scholarship, artistry and

spirituality. Monasteries reformed as centers of learning,

cathedrals began to be built and cathedral schools began to draw

professors and students to form the nucleus of European universities. The huge intellectual debt owed to the world of Islam

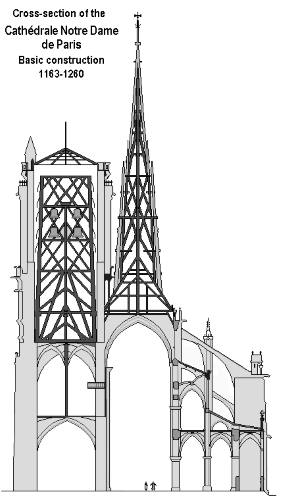

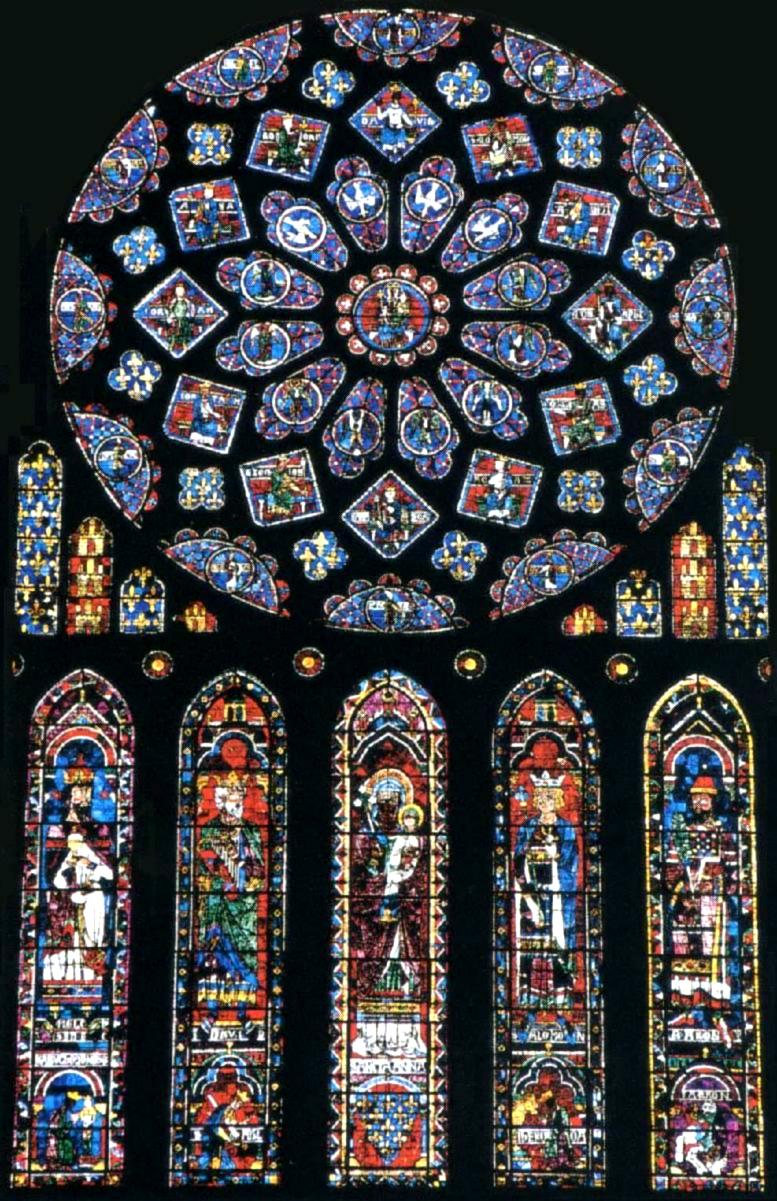

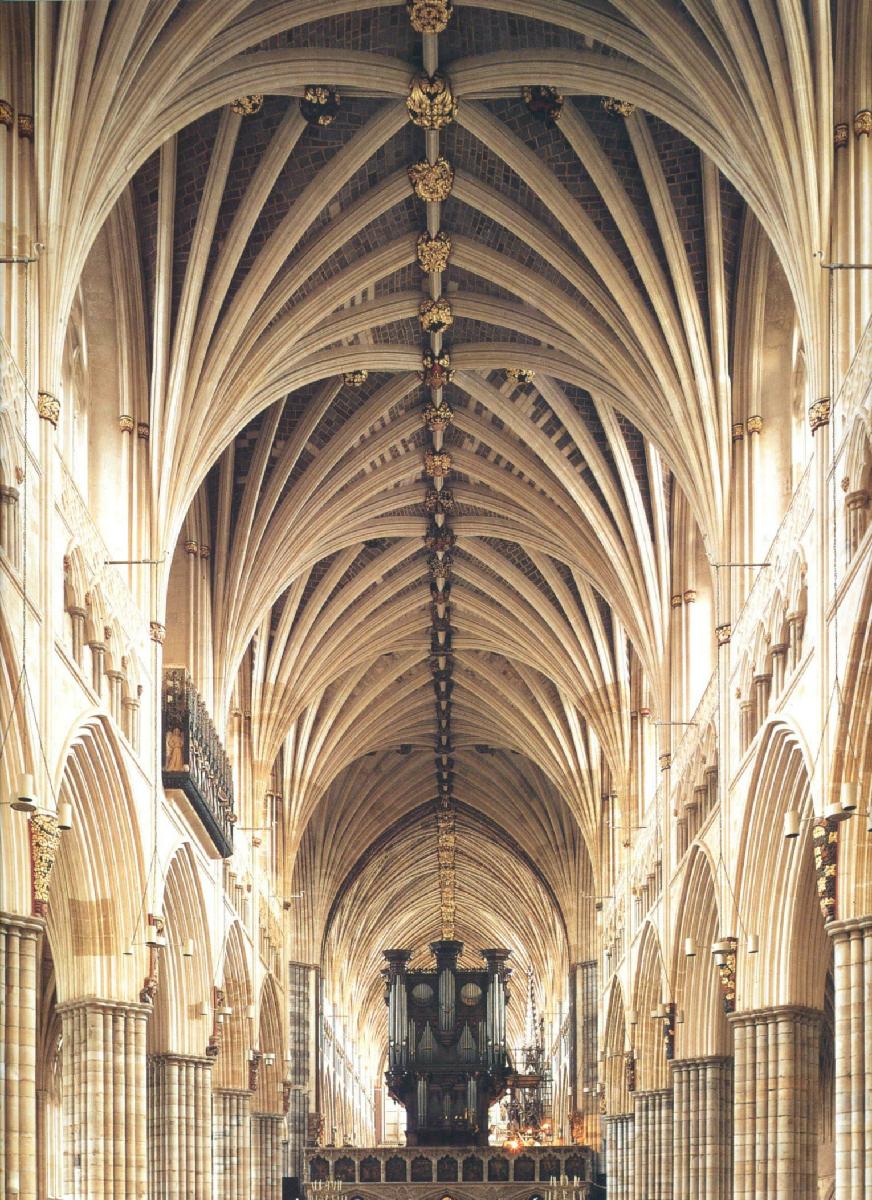

The new contacts (even the crusades) with the Muslim East had the unintended effect of assisting the Christian world in a major way in this new development of Western scholarship, artistry, and spirituality. In fact, even before the beginning of the crusades, there had begun a procession of Christian scholars to nearby Muslim Spain … to study Islamic medicine, mathematics, and general science. Classical scholarship. Thankfully the Muslims had rescued from earlier Christian purging of pre-Christian Greek literature a huge realm of ancient scholarship … scholarship which otherwise would have been lost forever. Some of the works of Plato and Aristotle had been preserved in the Christian West. But the works of other Greek scholars had been purposely suppressed … because of their "pagan" origins. But now with Muslim translations (and Greek originals) of the vast field of pre-Christian Greek scholarship quite available, Christian scholars could turn to the business of creating their own Latin translations of these formerly forbidden and thus forgotten ancient works … opening their world of Christian scholarship to new horizons. Mathematics. Contact with the world of Islam would have a tremendous impact on Christian culture and its offerings in other areas as well. For instance, it was from the Muslim development of al-jabr (the "completion") – which came to be known in the Christian West as algebra – that Western scholarship was able to do its own advancing in the realm of mathematics. Cathedrals. Moreover, the new cathedrals that came under construction in the 1100s and 1200s were able to reach ever-higher in structure – and yet be built with walls of stained glass rather than heavy stone – because of the discovery of the Muslims' pointed arch. This arch is what allowed such light, airy and high-reaching ceilings … and huge, and awesomely beautiful, colored glass windows to serve as the side walls. This produced what is oddly enough termed "Gothic" architecture ... a term assigned to that particular architecture style by Italian critics of the Renaissance period that followed (1400s-1500s) ... who considered such architecture crude (thus Germanic or "Gothic"), even ugly, in comparison to the classic looks of the older Romanesque style! |

The Cathedral at Chartres, France

Gothic design constructed largely between 1193 - mid 1200s

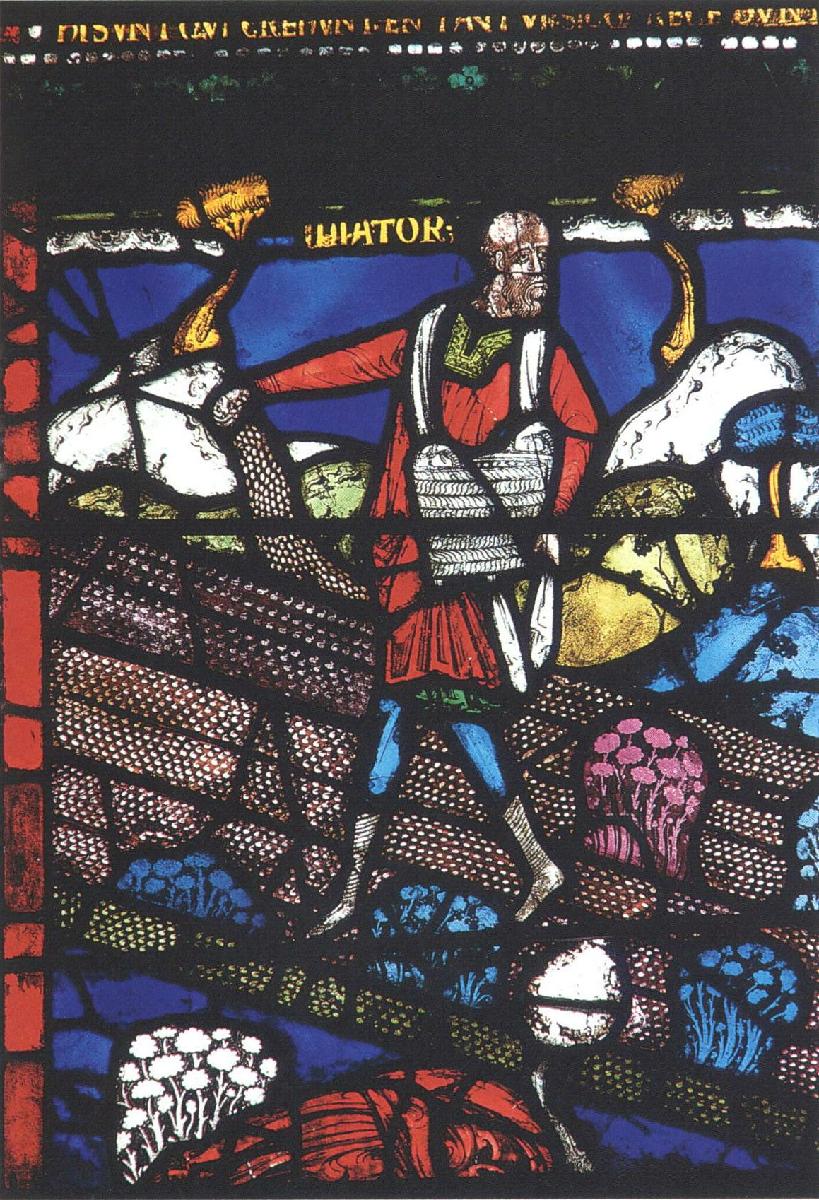

Stained glass window, Chartres

Cathedral (c. 1220-1230)

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris (1163 – early 1300s)

Sénanque Abbey – Vaucluse,

France (1100s)

Sénanque Abbey – Vaucluse,

France (1100s)

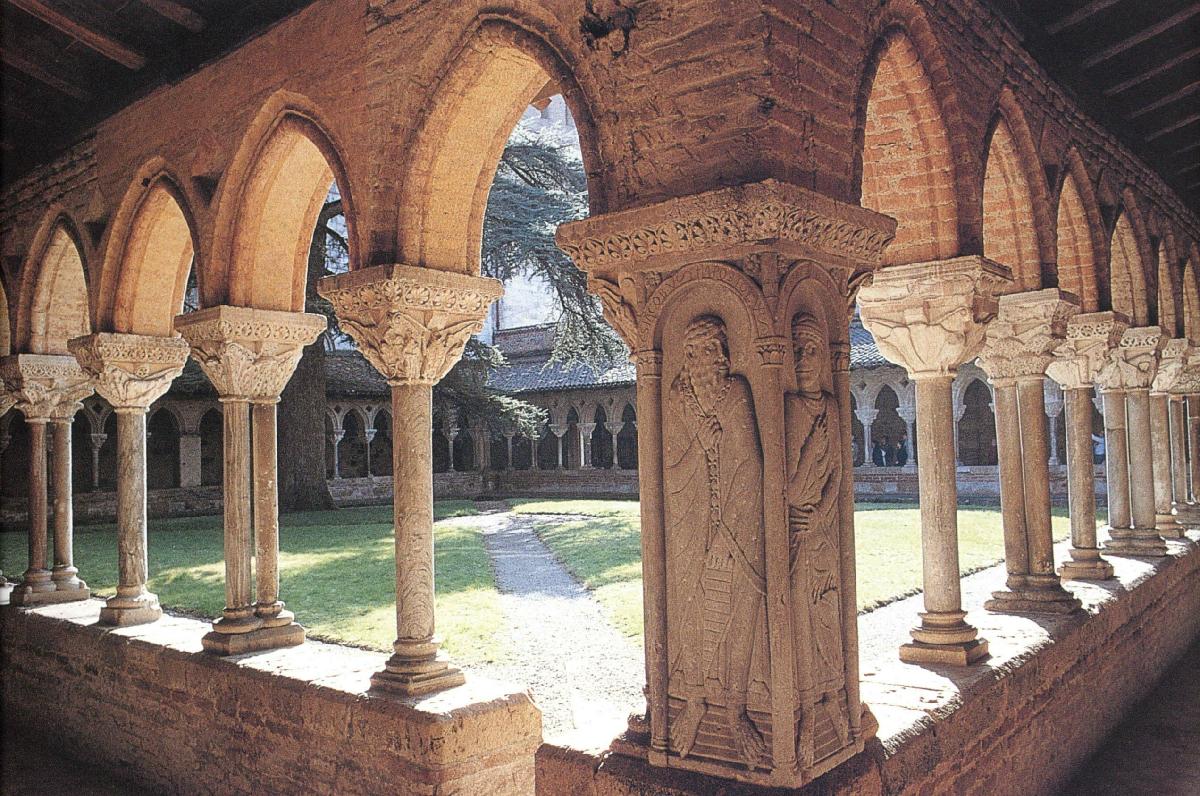

Cloister of the abbey church

Saint-Pierre de Moissac – Tarn-et-Garonne, France (late 1100s)

Nave, Cathedral of Amiens (c. 1220-1250)

The "Low Countries" of Flanders and the Netherlands

Central nave, Cathedral of Tournai, Belgium (early-mid 1100s)

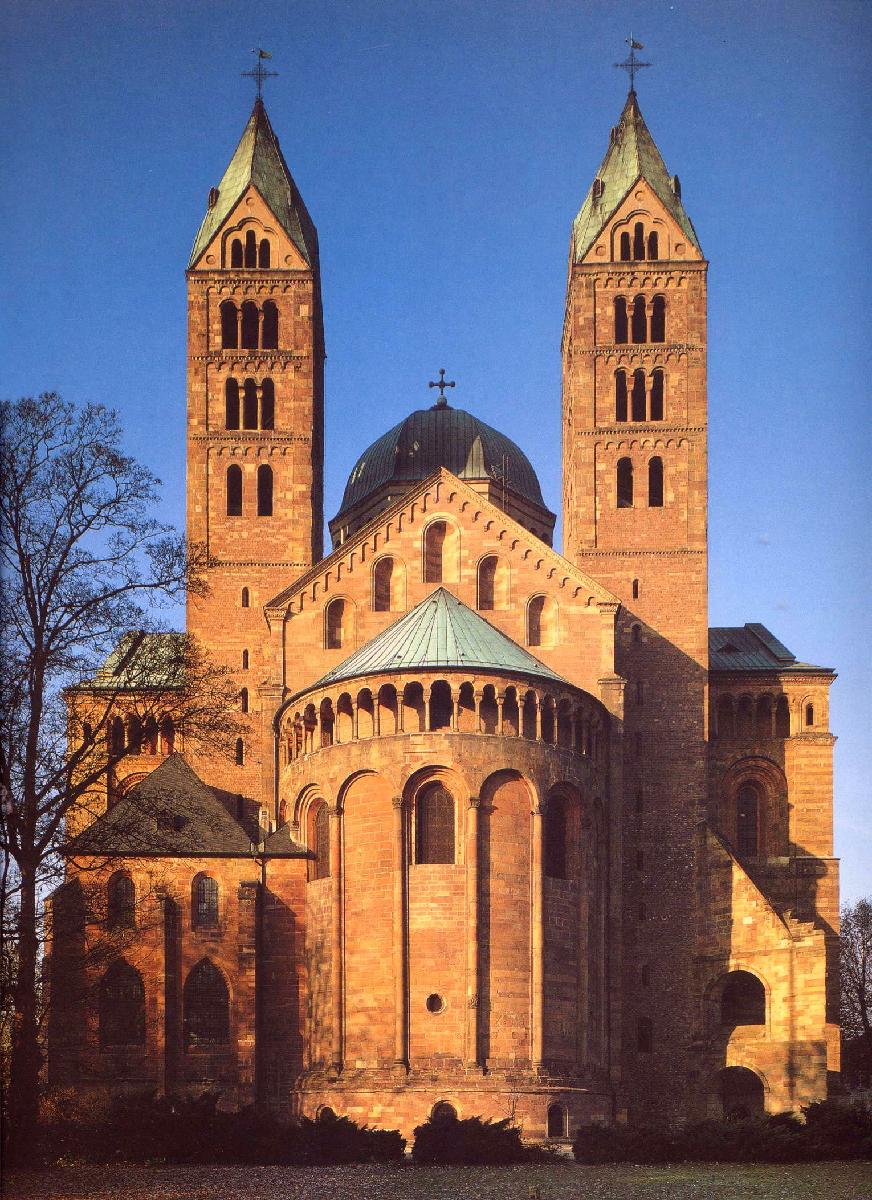

Eastern apse of the Cathedral of Spire, Germany (c. 1100)

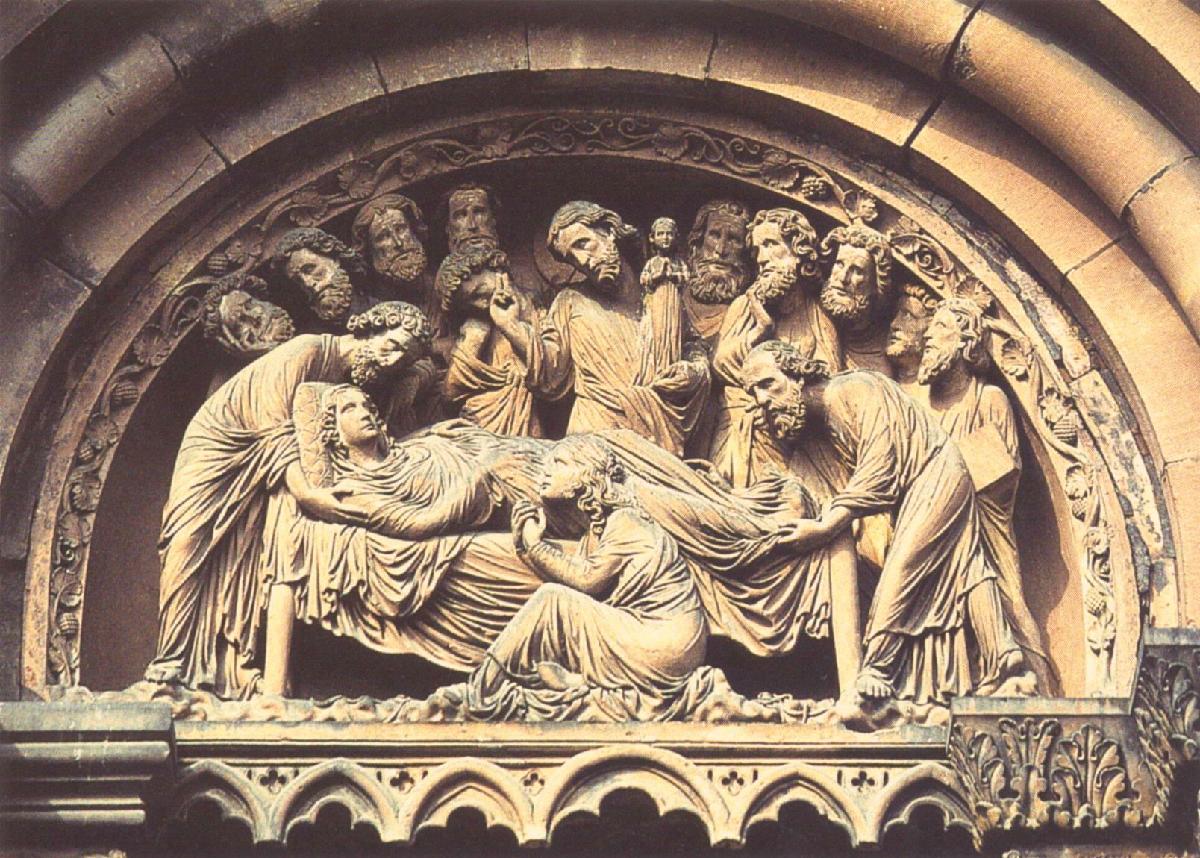

The Dormition of the

Virgin

(1220-1230) Tympanium,

Strasbourg Cathedral, portal of the south

transept

Bonn Pietà (c. 1300)

wood

Cologne, Rheinisches

Landesmuseum

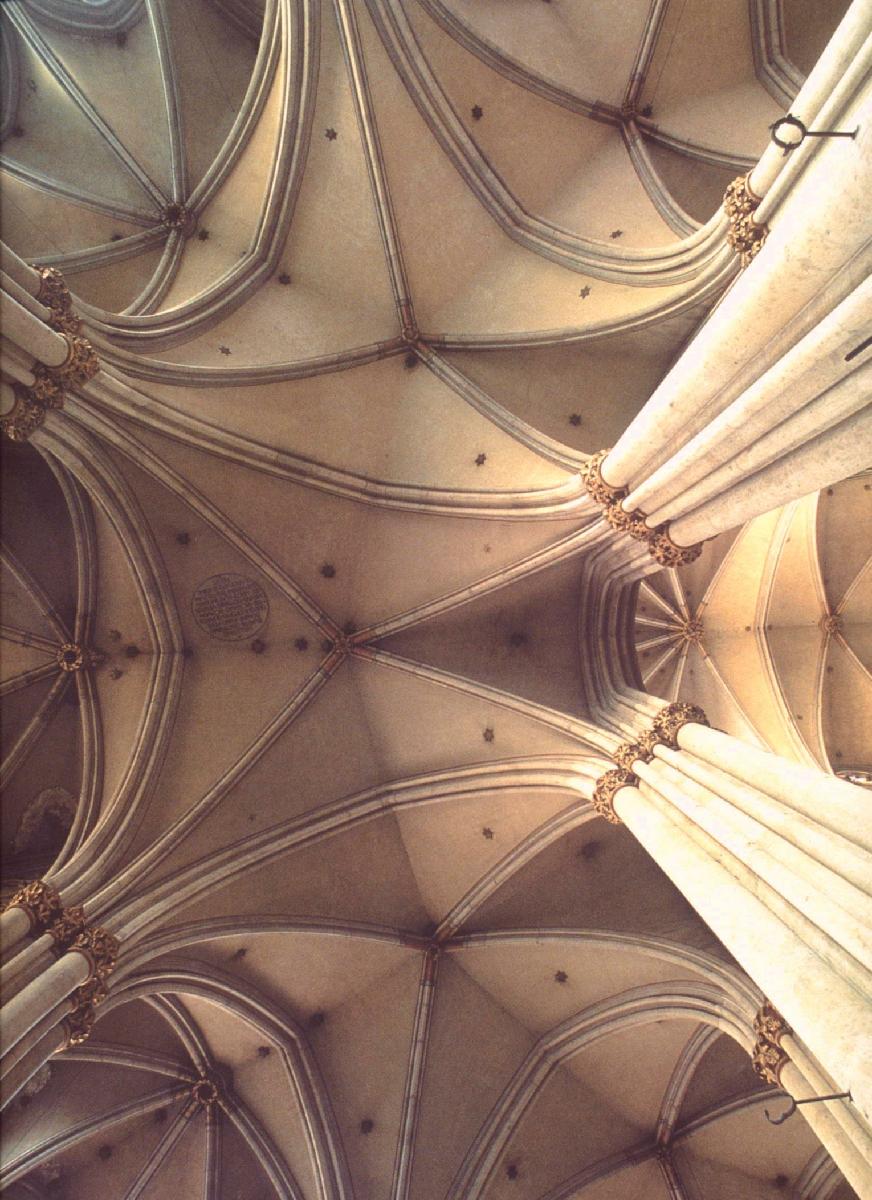

Ceiling vaults, Cologne Cathedral (1248-1322)

Vaults of the nave, Exeter

Cathedral (c. 1280-1290)

Detail of a stained-glass window, Canterbury Cathedral (c. 1180-1220)

The Cathedral of Burgos

(1221-1260;

upper portion and bell tower, 1400s)

Facade, Church of Santiago de Compostela (the Porch of Glory) 1188-1200

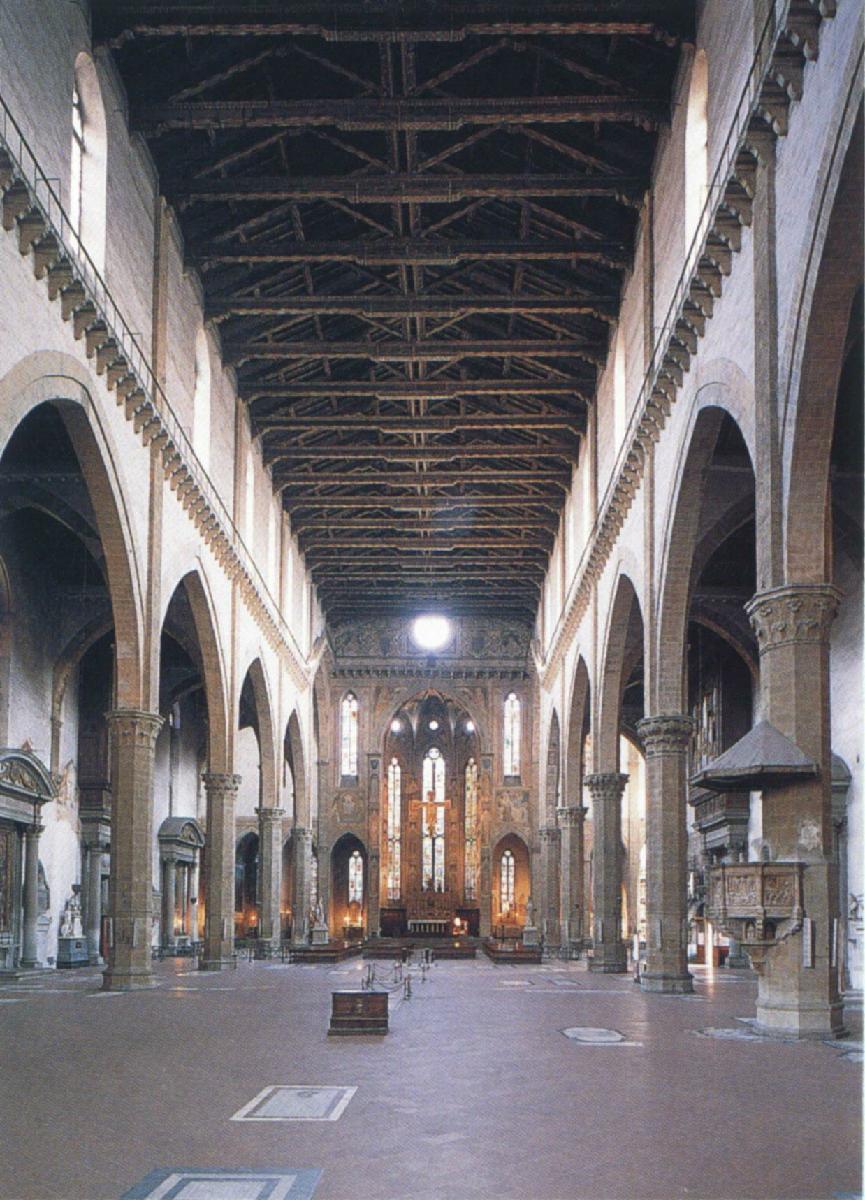

Italy tended to stay with the older Romanesque style

... though sometimes taking advantage of the Muslim arch

The Campo of Pisa

in the foreground, the baptistery,

1153-1300s; then the the cathedral, 1063-1200s;

behind the cathedral: the campanile (the "leaning tower"),

1173-1350

The Church of Santa Croce,

Florence (1295-1413)

"Romanesque" ... but notice the pointed arches!

Interior, Baptistery of Parma,

1196-1260

View of the apse, Church

of Saints Mary and Donatus, Murano (Veneto, Italy) 1100s

"SPIRITUAL HERESIES" ... DEVIATIONS FROM THE OFFICIAL ROMAN-CHRISTIAN ORDER |

| But

the new spirit arising in the Christian West would find itself going in

all sorts of new directions … ones which would upset deeply the keepers

of the older Christian social order. For instance, this

strong revival of the European intellectual spirit was also accompanied

by religious or evangelical "awakenings" among the common people –

often which had as its object the reform of an obviously corrupt

institutional church. This in turn brought Papal condemnation … for

mere disobedience and the embarrassment it caused Rome, as much as for

doctrinal errors. The Albigensians (or Cathars)

One of the principal heretical movements, brought back from the East during the crusades, was the Cathars (from Catharos, a Greek word meaning "Pure One") – also known as Albigensians from Albi, a town in southern France where the Cathars were numerous (also, northern Italy and Germany). The Cathars were dualists: believing that historical events were the product of the struggle of two forces, even gods – one good, one evil. Evil had dominion over the visible world; but through good works of extreme asceticism (including the avoidance of all sexual intercourse and the dissolution of marriages), the souls of individuals were restored to the Good God. Membership into the elect required such good works. According to the Cathars, being elect assured one of eternal salvation; but those who died without being saved were merely reborn into life (the living hell) and given another chance to try to achieve eternal salvation. There was no eternal hell to which the damned went. Furthermore, according to the Cathars, Christ did not truly have a human body – for that would have placed him under Satan's dominion; neither did Christ experience true bodily death or bodily resurrection. These particular elements of doctrine were held mostly by the more "sophisticated" of the Cathar community. The common people who followed the Cathar teachings did so mostly for the moral or ethical elements of the faith – not the doctrinal elements, of which they remained largely ignorant. In strong contrast to the times, women were admitted to the caste of "chosen" and could perform priestly rites – since sex was seen as a distinction only of the devil anyway … though usually only the men became evangelists and teachers out in the open world. The Cathars were exemplary people in their personal lives of piety and charity (in obvious contrast to the average run of Christian priests of the times) and well-loved in their communities. In the south of France they may have even become a majority of the population – though most of these Cathar followers would have continued to see themselves as "good Christians" and would have continued their observance of regular Christian worship. The Waldensians

Another heresy of the times was the Waldensians, named after their founder Peter Waldo (or Valdes), a wealthy merchant of Lyons who, around 1175 gave up his wealth and took up the way of an itinerant preacher of the gospel. He promoted the shocking idea that only scripture should be the ground of faith … and that any Christian belief or practice that had no scriptural warrant should be rejected. Though he gathered many local supporters, he unsurprisingly also drew the opposition of the local bishop for preaching (which was restricted to clergy). Tragically, an appeal to Rome in 1179 resulted in a refusal to support or even permit his work. For a time, the Waldensians observed the restriction – but then returned to evangelical preaching – resulting in their excommunication in 1184 (along with the Cathars – with whom they had nothing in common). However, excommunication and suppression seemed only to draw more support – principally in northern Italy and southern France as well as along the French and German Rhine. They also had adherents in northern Spain, in Bohemia and in Austria. Theologically, the Waldensians remained completely orthodox – on all points to which Scripture gave warrant. They even held out hope of being reunited with the church. But eventually, the more rigorous branch of the Waldensians in northern Italy began to select their own ministers to dispense the sacraments – putting a strain within the movement which wanted to avoid offending the church as much as possible. The crusade against the heresies

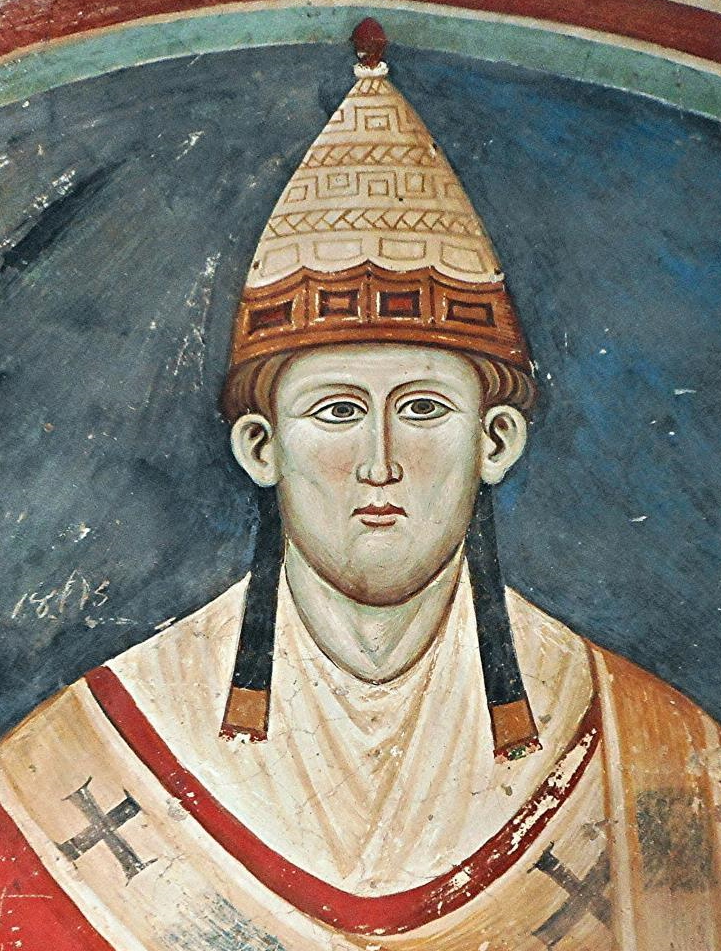

Distressed at the popularity of these grass-roots spiritual movements and the seeming danger they posed to the all-important authority of the Roman Church, in 1215 dealing with these heresies became a critical part of the business of the powerful Fourth Lateran Council … presided over by Innocent III. Not only were the Cathars declared to be heretics but so were the Waldensians … authorizing their brutal suppression (actually already underway at that point). In France, a crusade against the Cathars had already been announced in 1209 by Innocent III … and northern barons took this opportunity to invade the south of France in the quest of new lands. As a result, over the next 20 years southern France's cities and countryside were laid waste … and her culture shattered. In 1243 the last bastion of Catharism in southern France was destroyed. At the same time, the Waldensian movement was either destroyed or driven underground. Only in the removed heights of southern Switzerland did the movement hold out in any strength – until it was integrated into the Protestant Reformation 300 years later. |

Pope Innocent III (p. 1198-1216)

From a fresco at the Monastery of Subaico

Innocent not only called for the destructionof the Albigensians and Waldensians

he also authorized the creation of the Dominican and Franciscan monastic orders

... a very busy pope!

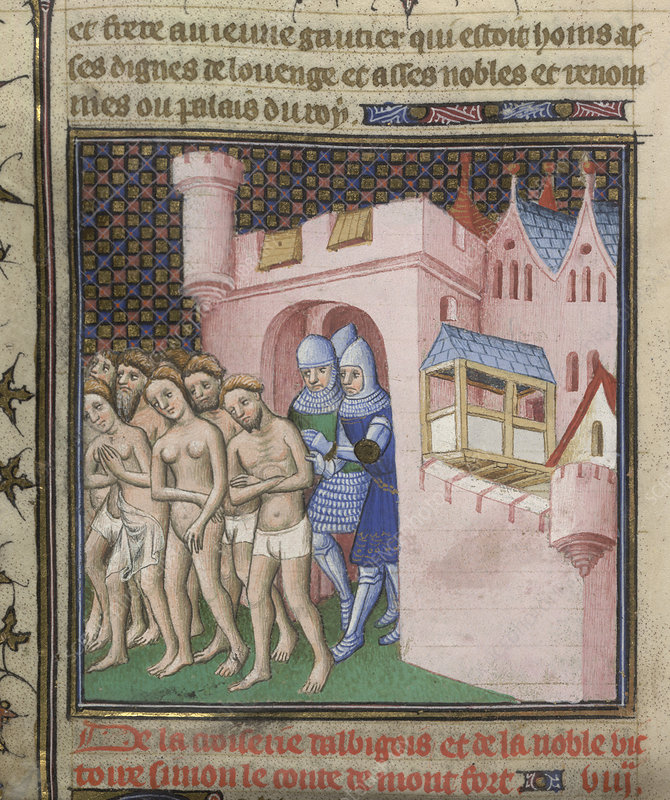

The Albigensians

1209 - Pope Innocent III calls for the eradication of the Albigensian heresy in Southern France

Thus Cathars being driven from Carcassone in Southern France in 1209

(a miniature illustration from the Grandes Chroniques de France - ca. 1415)

British Library

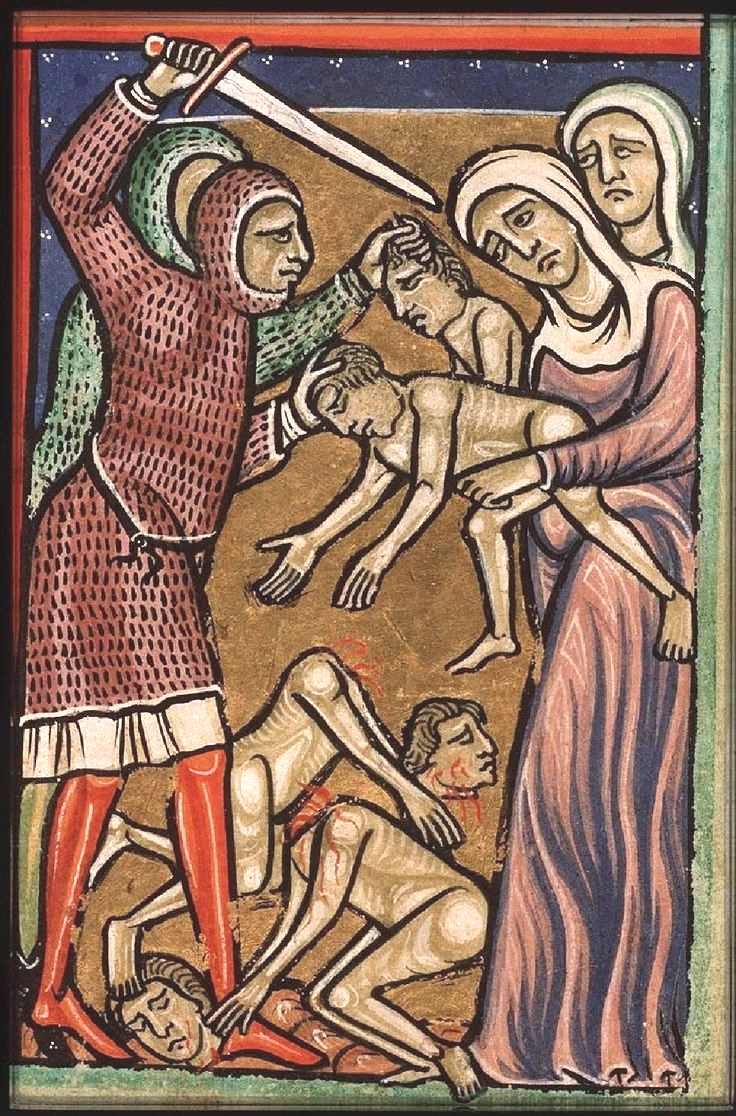

The "crusade" against the Albigensians turns to slaughter of the population ...

and destruction of the rich culture that had been developing in southern France

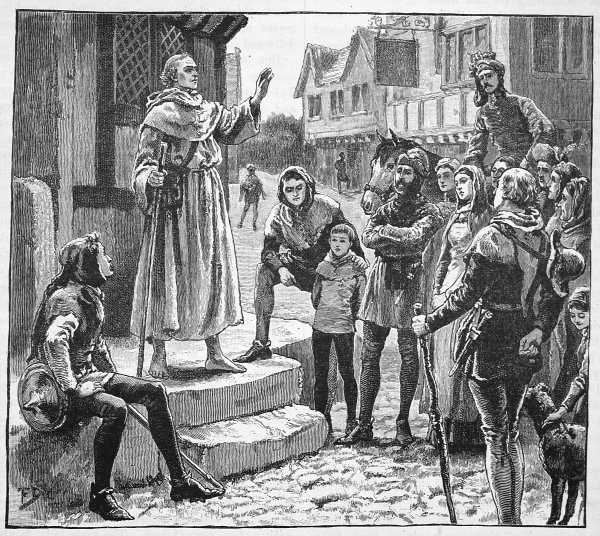

The Waldensians

Peter Waldo presenting an "unlicensed" Biblical sermon to fellow Christians - late 1100s

1215 - Pope Innocent III calls for the suppression of the Waldensians ... by whatever means necessary

A "Christian" campaign against the Waldensians – over the next 20 - 30 years

THE NEW TEACHING ORDERS |

|

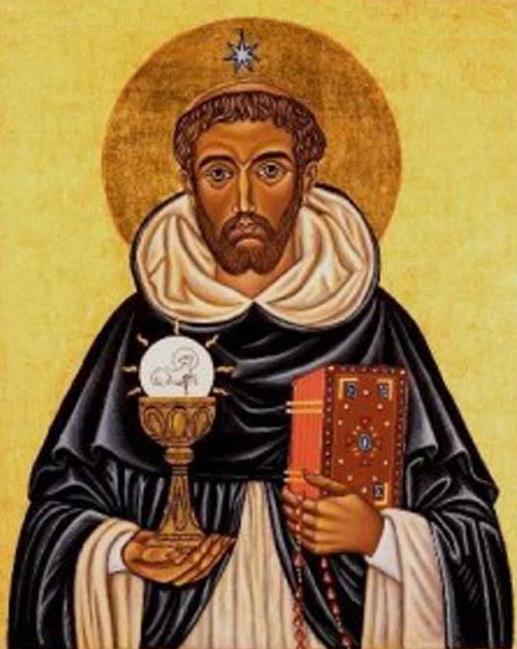

Dominic de Guzman (1172 1221) and the Dominicans

In the early 1200s, a Spanish Augustinian canon, Dominic de Guzman, urged the local monks in Southern France to fight Waldensianism and Catharism by emulating the apostolic poverty of the heretics – thereby winning back the support of the people. As the Albigensian crusade swirled around him, Dominic actually began to organize a new but very orthodox teaching movement, ultimately receiving papal recognition in 1217 as the Order of Preaching Brothers – though the term "Dominicans" became the popular designation of this new order. This evangelical and service organization spread rapidly throughout all Europe, reaching by 1230 from England and Spain to Denmark, Poland, Greece and the Holy Land. In short order also, the Dominicans were given chief responsibility in administering the Inquisition (which was in direct violation of Dominic's original understanding of their mission). But also, they also sought and obtained professorships in the new universities, becoming highly influential within the life of the institutional church. Francis (Giovanni Bernardone) (1181 1226) and the Franciscans

Of a different order of things was the movement started by Giovanni Bernardone of Assisi, Italy. Giovanni himself was given the nickname, "Francesco" (Francis or "Frenchman") because of his family's business trading with the French. Francis was a man who in so many ways gave humankind a most visible characterization of the very nature of Jesus Christ ... deeply caring for others, especially the ones most likely to be rejected by society: the poor, the outcasts (notably lepers), the most common of commoners. But by the same spirit, he could bring the very wealthiest, most socially noble, to join him in the same work with the poor and outcast. He could identify with both worlds, high and low, because he was born into considerable wealth as a son of a very prosperous Italian cloth merchant. Yet as a young soldier he fell into the lowest condition in life as a year-long prisoner in a horrible prison ... where finally the payment of a huge ransom brought him out of captivity ... but as a very sick person. But he early on found himself receiving words from God ... most mysteriously at first – and then by ever-deeper spiritual discipline (hours in prayer) as he developed. In 1206 or 1207, he received a totally life-changing call from God to "rebuild my church" – which he did (morally and spiritually), at first with some of his father's money. This got him in deep trouble with his father (who expected his son simply to take up the family business) and local authorities. And, to the shock of all, when brought before a town gathering presided over by the local bishop, and forced to make a choice of which road he was to take in life, he determined to shed himself of all earthly connections (including even the clothes he was wearing at the time!) in order to be able to pursue this religious calling He at first supposed this call to "rebuild" was in reference to an abandoned and decaying chapel in the region … and proceeded to rebuild it himself, stone by stone. This attracted onlookers … whom he engaged in discussions about God, Christ, salvation, etc. Soon a crowd joined him in his work. Then he began to see his call in larger terms: to devote himself to serving the hungry souls around him, especially those among the poor and socially marginal (something he had been doing for years, although originally only as a side line). He had no plan, no long-range goal except to live and serve as Christ had done, rebuilding Christian communities and aiding the poor, the sick and the outcast. Soon joining him in his work was a whole community of fellow workers ... future Christian evangelists. Thankfully, he succeeded where the Waldensians failed – ultimately gaining papal authorization for his work … though he had come close to being declared one of the heretics bothering the institutional church in those days. However, he was willing (though slow to actually do so) to put himself and his group under papal supervision. Thus in 1215, his movement was recognized as the Friars Minor (lesser brothers) by Pope Innocent III. But the Franciscans became fully organized under the subsequent pope Honorius III (1216-1227) as a newly-recognized monastic society ... through the considerable help of cardinal Ugolino. Francis himself retreated more and more from the responsibilities of leadership, having little heart in seeing his movement institutionalized. When he died in 1226, he died as a very smple monk within his own monastic order! But two years later, with Ugolino as the new pope Gregory IX (1227-1241), Francis was declared officially to be a Christian saint ... an unprecedented speed by which this process occurred – so great had been the impact of Francis on his times (and even since then!). And his Franciscan Order, inspired by his charismatic legacy, spread rapidly throughout Europe – in parallel with the Dominicans. However, not surprisingly, the Dominican and Franciscan scholars actually vied with each other for intellectual leadership of Europe … with the Franciscans a bit more mystical (Platonic-Augustinian) and the Dominicans a bit more naturalist (Aristotelian).  For more on Francis of Assisi For more on Francis of Assisi

The Augustinian Friars

From this point on, the Augustinian Order spread quickly around Europe – not on the basis of some well-organized effort but instead rather spontaneously here and there … because the order clearly met the spiritual hunger growing with the times.

|

Dominic de Guzman ... founder of the Dominicans

Dominican or "Black Friar" monks

The Franciscans

Francis receiving the "stigmata" of Christ – by Giotto (1290)

The dream of Innocent III ... seeing Francis supporting the church – by Giotto (1290)

This finally convinces him that Francis and his group are to be supported, not suppressed

Upper chapel, Basilica of St Francis, Assisi

Pope Honorius III confirming

by papal bull the revised rule of the Franciscans

Franciscan or "Grey Friar" monks

SCHOLASTICISM ... AND THE RESTORATION OF "HUMAN REASON" |

The Old University of

Bologna buildings – founded in 1088

A meeting of the doctors

of the University of Paris – founded from older Paris

schools ... but officially recognized as a university or guild of masters and

scholars around the middle

of the 1100s

From a

medieval manuscript

of "Chants royaux". Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark

|

Anti-Scholastic Skepticism

However not all great European minds were willing to go down this same path of holding human reason itself to be of divine nature Duns Scotus (1265 1308). One of the early voices to attempt to back down a bit from all this Scholasticism was Duns Scotus, an anti Thomist Franciscan. He felt that the study of creation neither was the pathway to an understanding of God nor an affirmation of the basic harmony of life. Each thing in the universe had a distinctness about its own existence. This was the foundation of reality: the world is made up of a multitude of separate things which have their existence quite independently of the existence of their defining "forms." It is this separateness between particular things and common forms that calls forth human thought – forcing the human mind to make the connection between form and particulars. This exertion of the human mind, however, is what gives dignity to human life and is reflective of God's own determining influence on nature. God, in all his sovereignty, is not limited to the rules of human reason in the way he operates. God is not under any constraint to work within the logic of "forms" or "universals" – but can create anything as he particularly sees fit. Plato's (and Aristotle's) "universals" are not compelling as the starting point of knowledge. Further, there is no way that we can use science or the study of the physical world to reflect back to the nature of God. The physical world we see around us is the product of free choice of God – who is able to make this world any way he wants to. His choices reveal no necessary qualities about God. With this last idea, Scotus began undermining the confidence of medieval scholars who felt that human reason was going to be able to bring all reality – including divine reality – under human scrutiny (and ultimately control). To Scotus, the exercise of human reason was good – even necessary, even dignifying of the individual. But it was not going to usher in some great age of human management of life through human reason. William of Ockham (1285 1349). In a way, Ockham was even more hard hitting than Scotus in his critique of the optimistic rationalism of the scholasticism of his times. This English Franciscan living in Paris was an ardent nominalist, claiming that what was truly "real," that is, open to human understanding through direct observation and reason, were the individual or particular things belonging to the physical world. However, the mind naturally reached beyond this reality to create broad mental categories or universals (names for things, thus "nominalism") of closely related particulars. Thus the mind created for its own logical use the category of "dog" – a broad class of all animals that we recognize individually as dogs. In this the human mind was abstracting from the particular to the universals (Plato's "forms"). But these abstractions or universals had no reality in themselves. "Universals" were only mental constructs, nothing more – useful, of course, in helping us come to some kind of appreciation of reality, though by no means 100% reliable as a tool for establishing the truth of things. Ockham was thus a skeptic with respect to the claims made on behalf of "human reason" by the scholastics of his day (anticipating David Hume by centuries). From this observation resulted "Ockham's Razor": the idea that we must be very careful in our use of human reason not to become too complex in our rational handling of particulars – lest we leave reality behind in the process. The simplest explanation of things is not only the more testable of things, it is normally the most accurate explanation of things! With respect to religion, Ockham (echoing Scotus) pointed out that we cannot move in our reasoning from our observations about the particular aspects of creation to produce general conclusions about the Creator. God is not constrained to work according to the rules of human logic. Logic, in fact, can tell us nothing about the nature of God or of ultimate things in creation. God can be known only by faith – a quite different enterprise than using logic. Only faith, not human logic, can touch God's absolute sovereignty and freedom. Ockham, in an effort to rescue faith from Scholastic rationalism, acted to sever the relationship between religion and secular science, a unity which Aquinas had worked carefully to develop. To Ockham, reason was a useful tool for observing the natural world. But it was useless in probing the realm of God. Only Divine revelation, received through human faith, would bring us knowledge of that higher realm. Ockham's nominalism had the effect of freeing secular science from theology. Science no longer had to serve as the handmaiden of theology – or be justified by its theological value. But at the same time, neither did theology require anything from science in order to validate itself. The Decline of Scholasticism

Thus in the 14th century(1300s) the via moderna (modern way) was born – rising to challenge the via antiqua (old way) of Aquinas. Thirteenth century scholasticism, built on the rationalism of Plato and Aristotle, came under challenge. So did the world view of the Christian Middle Ages – and all of its certainties. The contradicting positions of Aquinas, Scotus and Ockham not only undermined the unity of scholastic thought – they produced on going schools of thought which deepened the divide. Further, scholarly thinking lost its freshness as scholars seemed more focused on carrying on these old debates to the point of total tedium. As the freshness died, so did the vitality of the scholastic enterprise at the universities. Finally, the Black Death of the mid 1300s and the too obvious politicization of the church (at about the same time) put the finishing touches on the collapse of the rational certainties of medieval scholasticism. |

William of Ockham

All Saints Church, Ockham, Surrey

MYSTICISM |

| Yet

at the same time, while scholars argued over the nature of human reason

and the location of absolute Truth, the hearts of the common people

(and some not so common!) still continued to seek, perhaps even more

devotedly, a deeper, more vital personal relationship with God. Religious mystics, such as Meister Eckhart, Jan van Ruysbroek, Walter Hilton, Julian of Norwich, and Catherine of Siena, plumbed the depths of the soul and its relationship to God – and left records of those journeys for others to consider. Thus Christian mysticism flourished richly right alongside a growing humanism during these times. These "mystics" were looking for the great Truths of life not through systems of reason or intellect, but instead simply by seeking a personal piety by way of a direct spiritual contact with God. This piety tended to distance itself from religious formalism (the outward observance of religious rites and ceremonies) and to focus instead on the process of spiritual conversion (inner reform of the heart). Others pushed even further in their quest for "unity" with God, seeking true "mystical" experience Hildegarde of Bingen (1098 1179)

An early leader in this movement were and Hildegard was an amazingly prolific writer, artist, musician, poet, doctor and herbalist who was also the abbess of a dual male/female monastery. Much of her reflective work survives to this day. The Rhineland mystics were strongly influenced by her works two centuries later.  Musical Compositions Musical CompositionsJoachim of Fiore (1132 1202)

The Church and the Mystical Impulse

The "experiential" impulse within Christianity, despite domestic crusades and despite the orthodox teaching of the Dominican monks and the regular clergy, was always hard to contain by hierarchical authorities. The masses always stood ready to be swept up by any new wave of spiritual revival – a constant source of threat to the political position of the church, for such spiritualism was always privatistic and by-passed the official church with its energy. The church hierarchy watched these developments rather nervously, fearing that they might produce among the faithful a tendency to seek one's own way to God apart from the administration of the graces and sacraments of the church. Also, new mystical orders grew up almost spontaneously around Europe – much to the chagrin of the church. Combined with the rapid spread of the teaching orders (principally Franciscans and Dominicans), the priestly church hierarchy was losing its grip on the scheme of things. The "church" was coming more and more to be understood as being within the hearts and minds of the faithful. The German or Rhineland Mystics (1300 to 1350)

By the early 1300s A group of German mystics was having a huge impact on the times. In fact, it would be this group who would actually lay the foundations for what would become the "Reformation" of the Church. In preaching (using the German vernacular) to the Beguines and Dominican nuns under their care, these particular mystics touched their feminine piety with their Dominican theology, with its stress on the care of souls and the importance of spiritual self sacrifice …. rather than physical or outward renunciation which at the time was understood to be the path of true piety. In short, they stressed the importance of a Christian life of service to others in need … rather than service to one's own sense of self-righteousness (much like the Spiritual Franciscans)! Johannes "Meister" Eckhart (1260 1328)

Eckhart urged the faithful to retreat from the world to search for this divine spark in the ground of their own souls, to discover there the nascent Word of God, and to become mystically reunited, not just with God but with "Godness" itself: to become one with Divinity once again. In his later life, as he came under suspicion of heresy as a neo Platonist or even pantheist, Eckhart admitted to having been guilty of "exaggeration" and in the last years of his life backed into a more orthodox Thomist position. Nonetheless, shortly after his death (1329) parts of his writings were condemned by Pope John XXII. Johannes Tauler (1300 1361)

Tauler, a Dominican and disciple of Eckhart's in Strasbourg and Basel, preached and taught a more orthodox view … that God gifts his people with a spiritual "ground" crafted in his own divine image. This is conferred as a matter of divine grace; it is not (as per Eckhart) "self-discovered" as a matter of natural property of the human being. To Tauler, the return to "oneness" with God is a matter of having our human wills united with God's – not a matter of absorbing our human nature into God's divine nature. Tauler's example and sermons (the only surviving part of his writings) had a great influence on the Rhineland school of mystics, and after them on Luther, because of his stress on suffering and self-denial (experienced poignantly during the Black Death) and on the reliance on grace as the center pieces of Christian faith. |

EARLY HUMANIST STIRRINGS |

|

The

natural inquisitiveness that peace and prosperity brought was met as

much by a new exploration of the immediate world of the believer as it

was by the new exploration of human reason, or even the glories of

Creation and its Creator. Musicians and poets touched the hearts

of Europe with a new love for the world which God had placed them

in. Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, and Chaucer, for instance, wrote

poetry and prose that also focused on human life as it was actually

lived by real people around them – objects of interest (though not yet

quite objects of reverence) in a world that had heretofore been focused

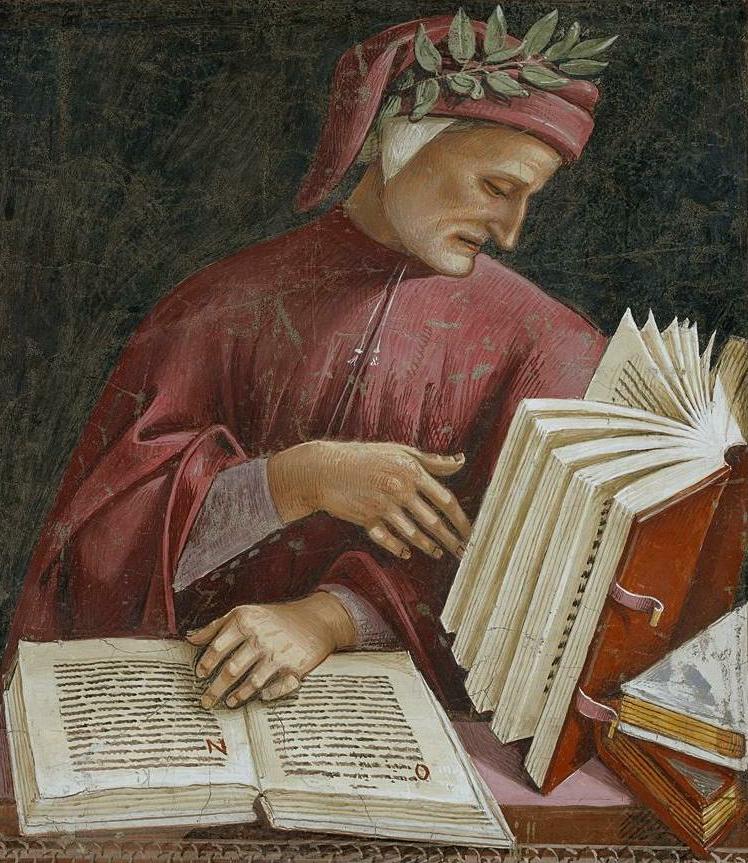

more on the life beyond this earthly existence. Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337). So also, the Florentine artist Giotto, though commissioned to paint religious art, designed his people to look real, very human, and quite alive – depicted as involved with others in the course of actual events – and not just formalized human icons who possessed only symbolic existence. His murals on the walls of the Arena Chapel in Padua are famous for his realism in depicting in various scenes the lives of Mary and Jesus … as well as his very life-like 27 murals in the San Francisco basilica in Pisa, depicting the life of St. Francis.1  For more on Giotto's works For more on Giotto's worksDante Alighieri (1265 1321)

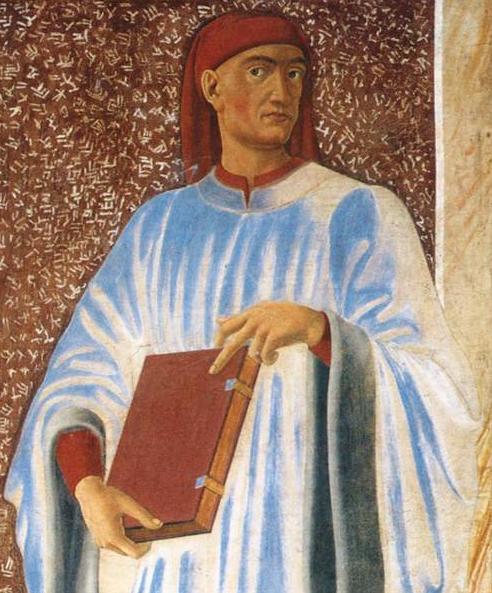

Dante would leave a huge impact on his times … daring to write magnificently in what he termed the "Italian" language – based principally on the Tuscan dialect of his birthplace, Florence – rather than on the classical Latin used rather universally. This was a major step in bringing the world of learning to the broader reaches of the common citizenry of Italy. But his work also connected the realm of religion and theology with the rising world of the ordinary passions of the people … especially the matter of romantic love. He himself was betrothed by way of contract at age twelve and ultimately completed the contract in marriage with Gemma Donati of the powerful Donati family of Florence. But at an equally early age he developed a love-at-first-sight condition with a female named Beatrice … whom he would in his later writings elevate to nearly divine status – even though his contacts with her had always been, and always remained, minimal. Rather, she became a symbol representing the power of "courtly love" which was rising at the time. Dante was ambitious politically, becoming early on involved with the Guelph party (pro-Pope)– which was politically dominant in Florence in his early days of politics – in opposition to the Ghibellines (pro-Emperor). He even served in a Guelph-Ghibelline battle in 1289 – thankfully coming out on the winning side. This would begin his political career. But the times politically were very unstable … and the Guelph party itself soon divided into two hostile groups, the Guelph Whites (and Dante) – tending to distance itself from papal rule in the quest for more political freedom – and the Guelph Blacks – eager for a tighter rule in Florence of the papal party. At first the Whites dominated, and expelled the Blacks. But Pope Boniface VIII intervened and turned the political tables in Florence against the Whites. Dante was then sent by the Whites to negotiate with the Pope … but instead was arrested upon his arrival in Rome. Meanwhile the Blacks took over Florence … and deep revenge was taken against the Whites (including Dante) who were expelled from Florence and their property seized. Thus in 1302 Dante found himself in exile. He would never be allowed to return to Florence. It was in exile that he did nearly all of his writing, La Vita Nuova (1294), a collection of poems and prose about courtly love, being the only work completed prior to that exile. His world of exile was not easy either. With the publication of his De Monarchia (1313 – actually written in Latin as a serious political study) his call for a secular monarch similar to the Emperor to bring peace to Italy (rather than solely the officers of the Church) distanced him further from the Church (the work was finally banned by the Church in 1515). But it was his Divine Comedy,2 written representing three stages of human progress … with Dante himself being the main character, and Virgil, Beatrice, and St. Bernard serving as guides in the three-staged journey: Inferno (Hell or the challenges of our earthly life); Purgatorio (Purgatory or the phase of the afterlife in which our sins are purged); and Paradiso (Paradise or our eternal reward as companionship with God in heaven). Stories of various individuals in his life were presented allegorically to portray this journey … all presented in a very beautiful poetic structure. Dante Alighieri, detail from

Luca Signorelli's fresco

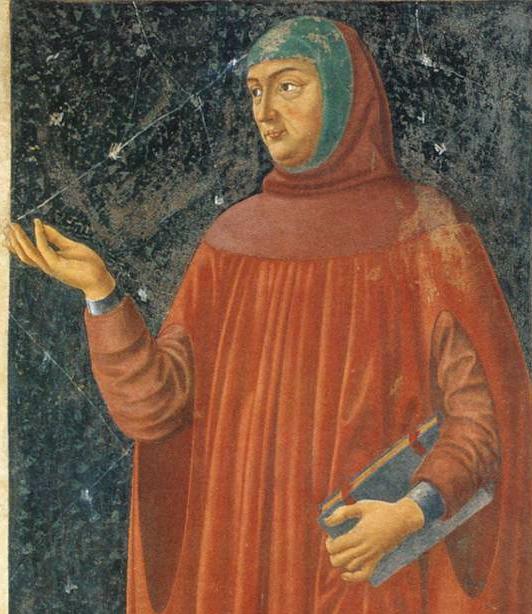

Chapel of San Brizio, Orvieto Cathedral Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374)

Petrarch

was born and raised in Arezzo in Tuscany to a family deeply involved in

the business of law. Although Petrarch himself was trained in the

law he viewed the profession as one in which a person made a

"merchandise" of his mind. Nonetheless he would be very active in

the world of politics, moving to Avignon and doing much of his work

there when Pope Clement V moved there to escape dangerous Roman

politics … beginning the long-running Avignon Papacy. Petrarch's

political involvement also sent him on ambassadorial missions around

Europe … which he used as an opportunity to collect historical

material, notably ancient Greek and Roman writings, which served to

deepen the foundations of his own writings. He continued the

tradition of writing in Latin … but focusing not on theological matters

(as was the habit of the time) but on historical scholarship.

Clearly he understood that something important was happening:

Europe was moving out of some kind of Dark Age into a new world of

Light … modeled closely on classical antiquity. It was thus that

his writings would have a huge impact of his times – and those that

followed in the 1400s "Renaissance" – in bringing forward not

traditional Christian but instead pre-Christian (Greek and Roman)

culture as the social ideal that his world should be imitating. Petrarch

was born and raised in Arezzo in Tuscany to a family deeply involved in

the business of law. Although Petrarch himself was trained in the

law he viewed the profession as one in which a person made a

"merchandise" of his mind. Nonetheless he would be very active in

the world of politics, moving to Avignon and doing much of his work

there when Pope Clement V moved there to escape dangerous Roman

politics … beginning the long-running Avignon Papacy. Petrarch's

political involvement also sent him on ambassadorial missions around

Europe … which he used as an opportunity to collect historical

material, notably ancient Greek and Roman writings, which served to

deepen the foundations of his own writings. He continued the

tradition of writing in Latin … but focusing not on theological matters

(as was the habit of the time) but on historical scholarship.

Clearly he understood that something important was happening:

Europe was moving out of some kind of Dark Age into a new world of

Light … modeled closely on classical antiquity. It was thus that

his writings would have a huge impact of his times – and those that

followed in the 1400s "Renaissance" – in bringing forward not

traditional Christian but instead pre-Christian (Greek and Roman)

culture as the social ideal that his world should be imitating.

Francesco Petrarch -

by Andrea del

Castagno Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375)

Giovanni Boccaccio - by Andrea

del Castagno

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400)

Chaucer

came from a well-positioned family in English society, serving as a

high-ranking public official … involving apparently much diplomatic

travel abroad. Possibly a trip to Italy had a huge impact on his

story-telling career. Chaucer

came from a well-positioned family in English society, serving as a

high-ranking public official … involving apparently much diplomatic

travel abroad. Possibly a trip to Italy had a huge impact on his

story-telling career.Certainly Chaucer was something of an English Boccaccio, also in his famous Canterbury Tales3 presenting, in the common English of the day, 24 stories told by various individuals (a knight, friar, physician, lawyer, clerk, miller, cook etc.) on a pilgrimage together from London to Thomas Becket's shrine in Canterbury, stories told simply to pass the time … but also done so in contest to see who could tell the best story! Here too, the motif was quite Humanist rather than theological. And thus Chaucer helped step English society into the rising world of the Renaissance. 1Giotto also happened to be an excellent architect, designing the beautiful bell tower of the Florentine Cathedral. 2"Comedy" at that time meant more a process in life that, with God's help, brings a person to the happy state of a well-ordered life. 3These were composed over a period running from 1387 to his death in 1400, not fully complete, as he had hoped to write many more such tales told by these same pilgrims. |

Go on to the next section: The Close of the Middle Ages

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges