PRIMITIVE SOCIETY

PALEOLITHIC SOCIETY

CONTENTS

The original social form: Paleolithic The original social form: Paleolithic

society

Paleolithic hunting-gathering bands Paleolithic hunting-gathering bands

The paleolithic worldview or The paleolithic worldview or

"cosmology"

Archeological finds and cave paintings Archeological finds and cave paintings

Recent examples of paleolithic hunting- Recent examples of paleolithic hunting-

gathering bands

HISTORICALLY

SPEAKING, THE ORIGINAL SOCIAL FORM:

PALEOLITHIC

SOCIETY |

We

start our study off with a look at the most original or primitive form

of sovereign society that we know of: paleolithic society – or

‘old stone age’ society. This is society as we believe it to have

existed at the very beginning of human life on this planet.

There are almost no such paleolithic societies left on this planet

today, for modern life has reached into their world and changed their

lives deeply. However only a century ago there were multitudes of

paleolithic societies still tucked away in various corners of the

earth, remnants of a social order we believe to be the one that all

human life started out with long ago.

Anthropologists went among these latter-day versions of these primitive

societies and recorded their doings and their thought processes – as

best they could given their own largely Western world view and thus

understanding or interpretation of life. There are a number of

things they described about these people that were similar – whether

they were describing life in New Guinea in the Southwestern Pacific, or

the Kalahari Desert in Southwestern Africa, or in the highlands of

southern India, or in the frozen tundra of northern Europe, or the

steamy jungles of Brazil. On the basis of this similarity they

were able to generalize key features of human life and order among

paleolithic peoples – generalities that it was easy to suppose also

held true for a social order that presumably existed at the dawn of

human history before civilization spread across the earth and changed

everything.

Paleolithic – and neolithic

The term ‘paleolithic’ itself refers to the level of development of the

stone tools and weapons of these primitive peoples. ‘Paleolithic’

means ‘old stone’ and referred originally to a basic crudeness in the

appearance such stone implements uncovered by archeologists in their

diggings around ancient sites of human habitation. Archeologists

noted that at these archeological sites the tools and weapons these

ancient people used were made from minimally reshaped stones.

When they contrasted these stone tools with the stone tools of more

advanced societies (much more carefully worked and shaped and more

effective for not only hunting but also for more advanced food

production) they grouped the former type into paleolithic (literally

‘old stone’) and the more advanced group into neolithic (literally ‘new

stone’) categories of ancient societies.

Anthropologists studying actual primitive societies still in existence

at the end of the 1800s were struck by how these societies still used

the same types of stone tools. And thus some societies, more

primitive than others, were labeled ‘paleolithic’ and some ‘neolithic,

even though anthropologists were not that interested in their tools –

but more interested in their social ideas, behavior and

organization. The terms worked well nonetheless – for they

noticed a sharp cultural distinction between the two groups, as if some

great social revolution had set the two types of societies apart.

Even though both groups were ‘pre-civilized,’ they were quite distinct

one from the other in quite significant ways. So the terms

‘paleolithic’ and ‘neolithic’ were borrowed from the archeologists

(people who study ancient social sites) by anthropologists (people who

study simple, but still living societies). The terms worked very

well for them – and they will help us in our study here as well./span>

|

PALEOLITHIC

HUNTING-GATHERING BANDS |

|

The paleolithic community: the "band."

Paleolithic man was a ‘food-gatherer’ rather than a food

producer. He planted no vegetables or grains – but hunted or

foraged for berries and roots that grew in the wild. He had no

domesticated animal herds of his own but hunted the wild animals around

him.

Hunting is not a very efficient form of human life support. A

huge amount of territory is required to sustain a very small human

community on the basis of the social economies of hunting and

foraging. Thus in general paleolithic society was based on very

small groups, which anthropologists call ‘bands.’ These bands

might be made up of no more than a dozen, or a couple of dozen,

individuals. These bands tended to be highly nomadic, on the move

constantly in pursuit of their next meal.

There were exceptions to this of course, especially if a community was

located in a prime spot such as along a well-stocked river or lake

where the fishing and hunting was excellent. Such communities

could grow to several hundred in size. But these were dangerous

areas – because human enemies tended frequently to fight the occupants

of such an enviable location for the privilege of living there.

Political organization

The headman. These

primitive paleolithic bands were organized along very simple

lines. Judging from the evidence of paleolithic communities that

we have been able to observe in more recent times, they tended to form

around a ‘headman’ who held the band together on the basis of his

hunting skills – and his esteem as one blessed by the world of

spirit. In fact his hunting skills were understood to be closely

related to his spiritual powers. Under his protection or guidance

were a small number of women and the children – and also a handful of

bachelor males. The latter were loosely attached to the band,

cooperating in the hunt and receiving a portion of the blessings of

community life – including perhaps some time with the women.

Women might also have been loosely attached – perhaps moving from band

to band as greater protection for pregnancy, nursing and child-rearing

was to be found elsewhere.

As the connection between a particular sexual act and the birth of

children nine months later was not particularly well understood, sexual

rights were more a matter of social privilege than parental right and

responsibility. Perhaps children were even thought of as

belonging to the community as a whole and not just some particular male

or female within the band.

There may also in fact have been a loose sense of broader relationship

among a number of such bands known to be hunting in a particular area –

where band members may have felt it okay to move among such bands for

longer or shorter periods of time.

Shamans. Of special

note were the shamans or witch doctors. They were understood to

possess special magical powers that could be worked to the good – or

the bad – of the community. As such, they were both greatly

respected and greatly feared by those around them. Being thus

endowed with exceptional spiritual powers, they usually were better

appreciated at a distance. They did not usually live with any

particular band but practiced their trade in a wide area that would

include a number of related bands. These individuals may in fact

have considered a large region accommodating many different bands as

their spiritual territory, drifting in and out of the life of the

various bands as the occasion required. They would possibly be

invited into the precincts of a particular community only when their

services were required, usually in the healing of a sick member of the

community, be paid off in food for their services, and then be blessed

as they moved on.

|

THE

PALEOLITHIC WORLDVIEW OR "COSMOLOGY" |

|

Paleolithic culture: "Animism"

The paleolithic worldview. Paleolithic man lived very close to nature,

being really a natural creature himself. He lived on the basis of

the food he could find or hunt – much as the rest of the animal

kingdom. He grew or produced nothing by way of his own food

supply. He depended entirely upon nature to keep himself alive.

Actually we have to be careful using the term ‘nature’ for that is a

modern concept – separating the visible world (nature or the ‘natural’)

from the unseen world (the ‘supernatural’), the latter world having

come under considerable disrepute of late by much of our scientific and

scholarly community. Paleolithic man made no such

distinction. To him there was no natural versus

supernatural. They were both one and the same.

To paleolithic man there was a great dynamic to all of life, not only

all of life around him but also his own life. Life was

basically a struggle, though a harmonious struggle, in which everything

fed everything else so as to produce a constant flow of life and death

around him – and even within him. He did not see life as we

moderns do today – typically a rather mechanical process of physical

laws operating on largely distinct objects making up the material world

around us (and of which we are also a part). Rather, paleolithic

man saw life as essentially what we would term today ‘spirit.’

Spirit gave life. Spirit fashioned behavior – of not only both

man and beast, but also of trees and rivers and mountains. Spirit

caused things to ‘flow.’

Anthropologists were intrigued at how paleolithic man saw spirit

inhabiting everything – things even such as rocks and rivers and

mountains and stars to which the Westernized anthropologist would never

have thought to assign ‘life.’ The paleolithic man assigned life

or spirit to everything – seeing ‘animation’ or life all around him.

Thus the anthropologist ultimately assigned the term ‘animism’ to

paleolithic man’s belief system or world view. And this probably

is an accurate description of how paleolithic man indeed did see

things. To paleolithic man, all of life was activated or

‘animated’ by spirit. The workings of the world of ‘spirit’ gave

action or life to everything that existed – including clouds, bears,

lightning, berry bushes, snakes, water falls, fish, high mountains, his

bows and arrows, his hut, his fire – and each other.

A parable of sorts

A young man heads off into the surrounding woods for a hunt of meat

(perhaps bear or deer) that will take him away from his small community

for a number of days. Upon his return he is devastated to

discover that in his absence a huge boulder had come crashing down from

the mountain that the community had nestled under and smashed into his

hut killing his wife and dog. In an effort to bring some sense to

this tragedy he consults a local witch doctor to see what he can learn

from him about what happened. In a trance which invites the witch

doctor into the world of spirit, the witch doctor explains the cause.

His dog had been chasing a rabbit up the mountainside – and had lost

out in the pursuit when the rabbit disappeared down a hole. The

dog took his frustration out on a huge boulder nearby by lifting a leg

and letting go a yellow stream on the side of the boulder – to which

the boulder took great insult. The boulder avenged the insult by

noting that the dog had entered the hut just below him – and decided to

act. The dog was crushed in the event. But so was the

hut. And unintentionally, the wife was crushed as well, an

innocent bystander in this drama. Of course his drama doesn’t end

there because now the young man has to find vengeance of his own.

Nonetheless that’s where our story will end.

This little and rather ridiculous story probably never happened, though

things like it certainly did in paleolithic culture. For this is

how paleolithic society saw all events. Life was a result of the

invisible workings of the spiritual world. The spirit or spirits

inhabiting all things set up the dynamic of life in concert with each

other – acting and reacting ‘behind the scenes’ to make things happen

as they did.

"Pre-enactment"

We have all probably seen pictures of young Indian braves or

hunters dancing around a campfire to a strong drum beat, chanting

and spinning. One of them possibly wears a buffalo skin and the

others seem to be focused on this particular individual. Very

likely they are ‘pre-enacting’ a great buffalo hunt, their actions

constituting a sort of spiritual ‘technology’ designed to align the

unseen spiritual world of the buffalo with their own spiritual powers –

in a way that guarantees their spiritual ascendancy or domination in

the contest of spiritual wills (theirs and the buffalo’s) that is soon

to take place with the beginning of the hunt. They may be very

expert bowman. But whether they actually succeed in the hunt

depends more on the spiritual alignment of their spirit or spirits

(along with possibly the spirit of the arrow or bow) and the spirit of

the buffalo.

Other "spiritual technology"

Likewise if the hunt brings success there are important spiritual

rituals to be performed. The spirit of the defeated buffalo must

be appeased – lest revenge of some kind on the successful hunter should

occur. Possibly there is a ritual in which the spirit of the

buffalo that his been brought down is also trapped and captured by the

successful hunter – adding to his own spiritual powers.

All of this may seem to a modern mind to be very unnecessary. But

to the paleolithic mind this is all very logical – and very

necessary. His world view informs him that all events in life

result from the actions of the spiritual world working in an invisible

way in and through the visible world. The visible world of

material reality is merely the outer form or dressing of an even

greater inner reality.

Is this spiritual world one or many? Are all the things that we

observe as single items (a tree, a brook, a hawk, a girl, a mountain, a

bow, a bear) comprised also of single, distinct spirit each – or is the

spiritual world a single Great Spirit that inhabits everything – or is

it some combination of the two? That really depends on how the

world view of a particular community (and its neighbors who probably

share a similar world view) understands these things. But one

thing is certain: its is spirit, not material or physical existence,

that is paramount in shaping or determining the course of existence.

|

ARCHEOLOGICAL

FINDS AND CAVE PAINTINGS |

The Laussel Venus - Gravettian

Culture (Dordogne, France)

Head of a woman known as

the "Venus of Brassempouy" – Gravettian (c. 27,000 BC) Mamouth

tusk

Brassempouy (Landes,

Frances)

Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Musée

des Antiquites nationales

Female statue known as the

"Venus of Lespugue" – Gravettian (c. 27,000 BC) Mamouth tusk

from Lespugue (Haute-Garonne,

France)

Paris, Musée de

l'Homme

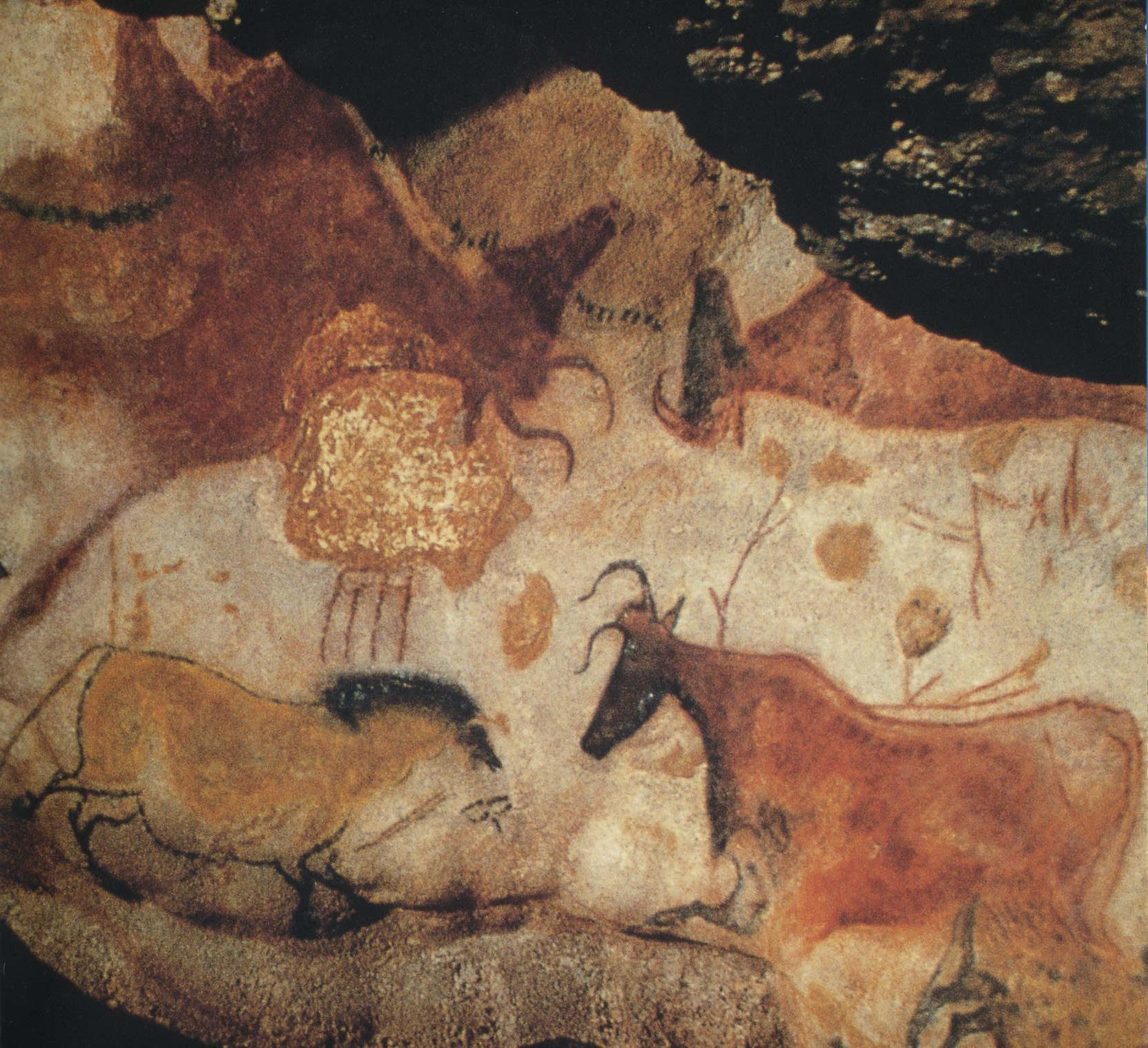

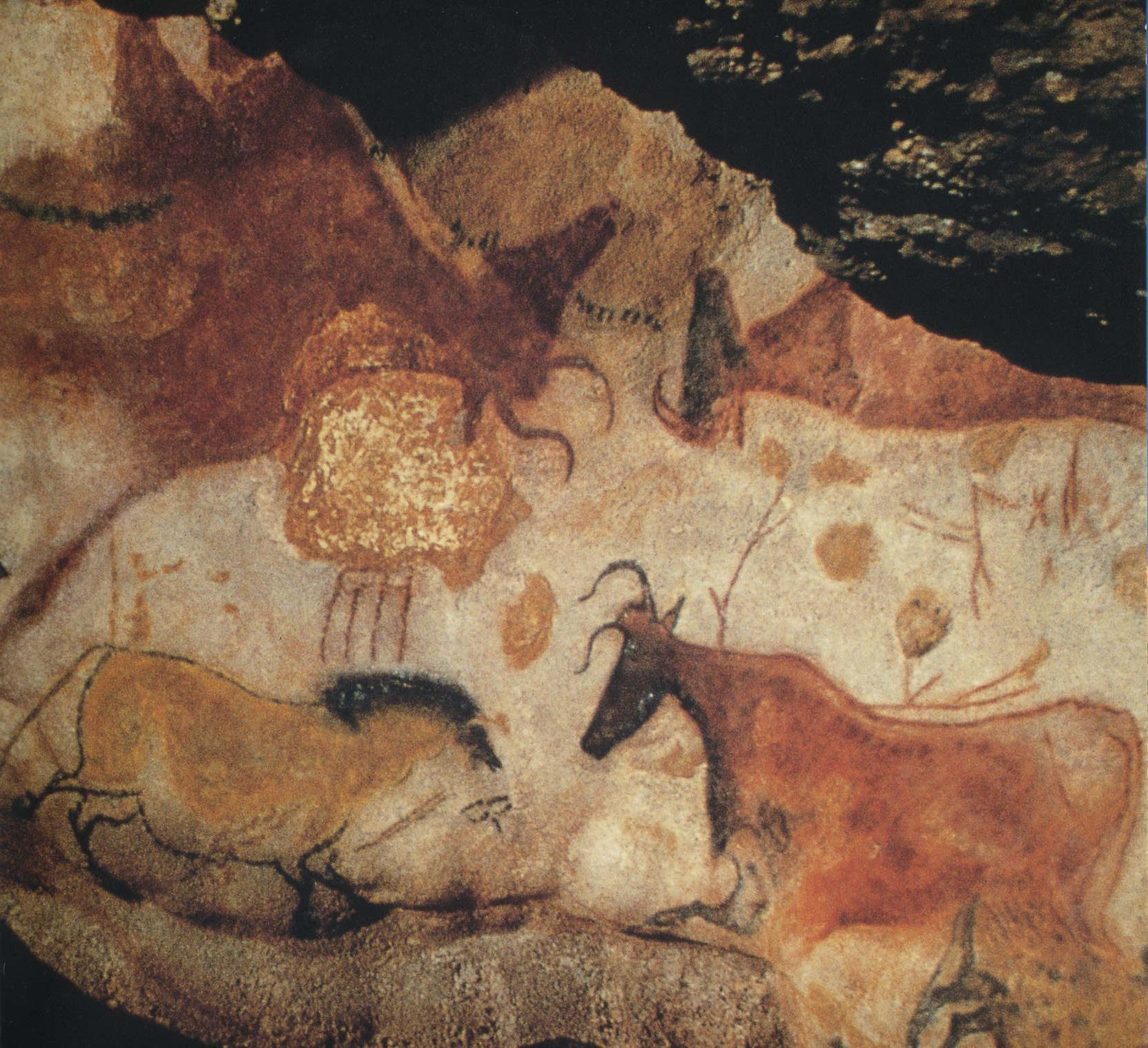

Lascaux Cave - discovered

in 1940

Lascaux Cave - discovered

in 1940

Cro-Magnon cave painting

from Lascaux, southern France (20,000 years ago)

Horses – Hall of the

Bulls, Lascaux Caves, France (c. 15,000 - 13,000 BC) paint on

limestone

Bull, horses and stag – Magdalenian

(c. 18,000 BC) detail of painted wall

Chamber of the Bulls, Cave

of Lascaux (Dordogne, France)

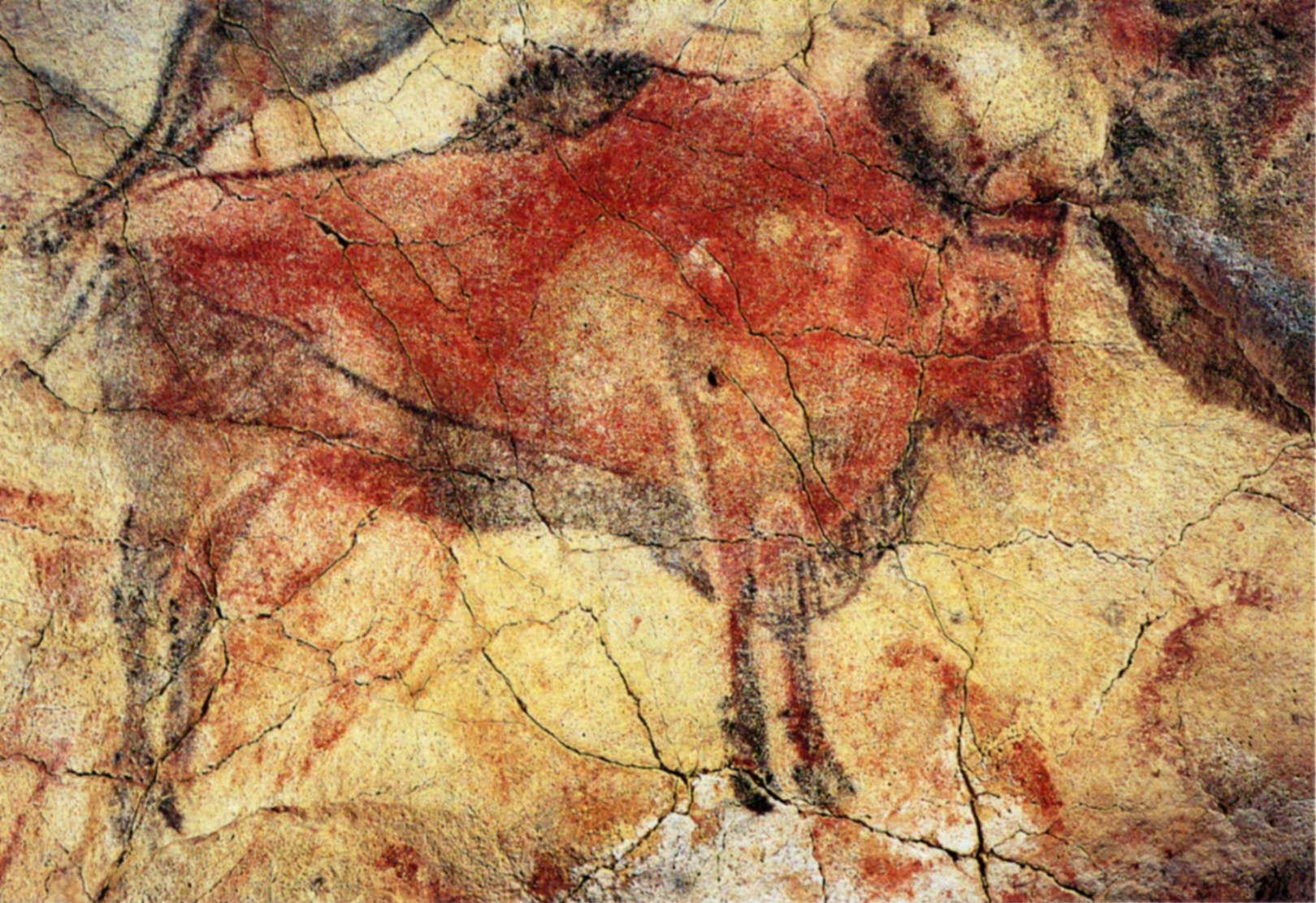

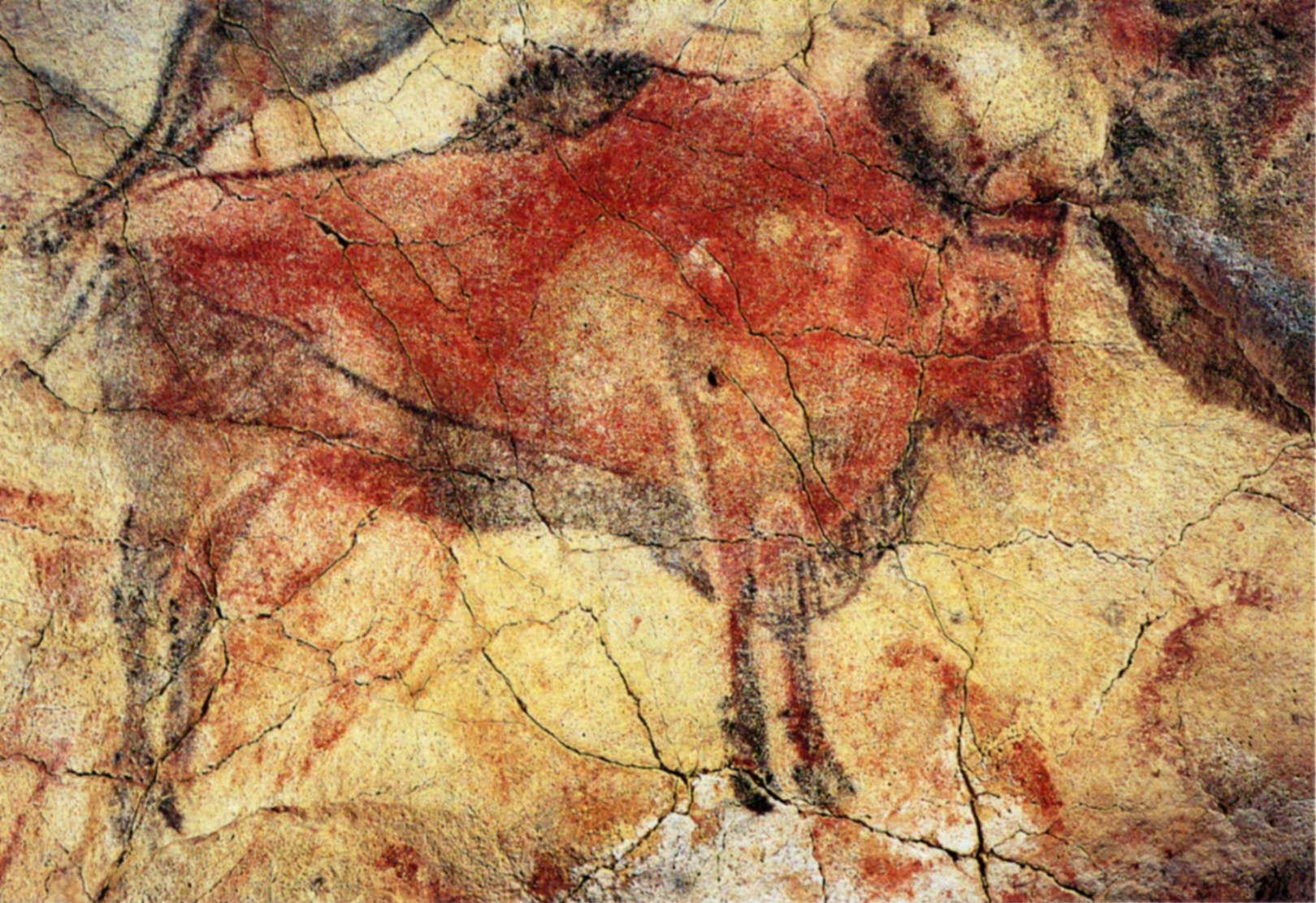

Bison – Altamira Cave,

Sandtander, Spain (c. 12,000 BC) paint on limestone

Bison – Magdalenian (c.

18,000 BC) deer antler

from the cave of La Madeleine

(Dordogne, France)

Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Musée

des Antiquites nationales

Painted stones – Mesolithic(c.

10,000 BC) stone

from Mas-d'Azil (Ariège,

France)

Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Musée

des Antiquites nationales

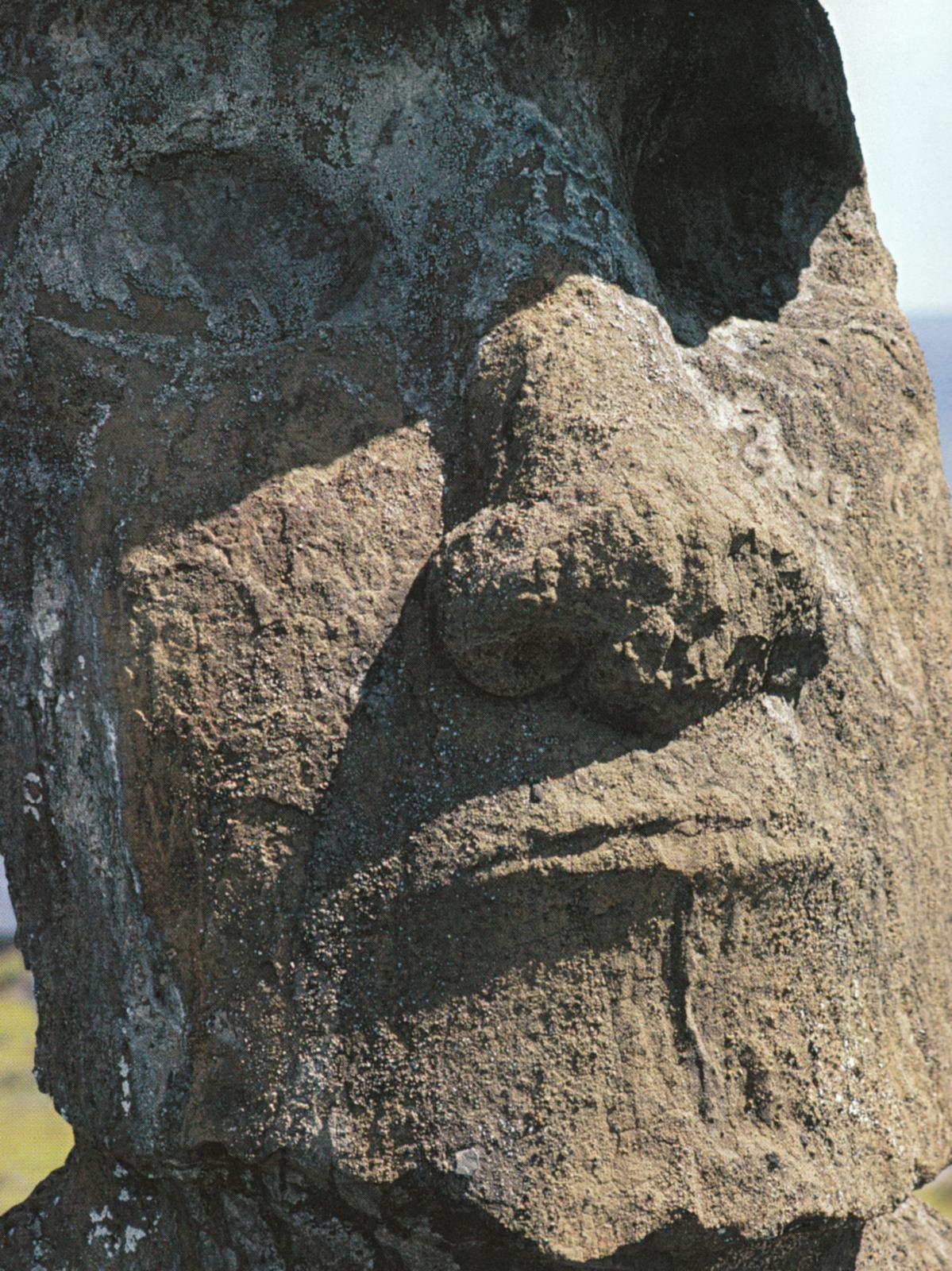

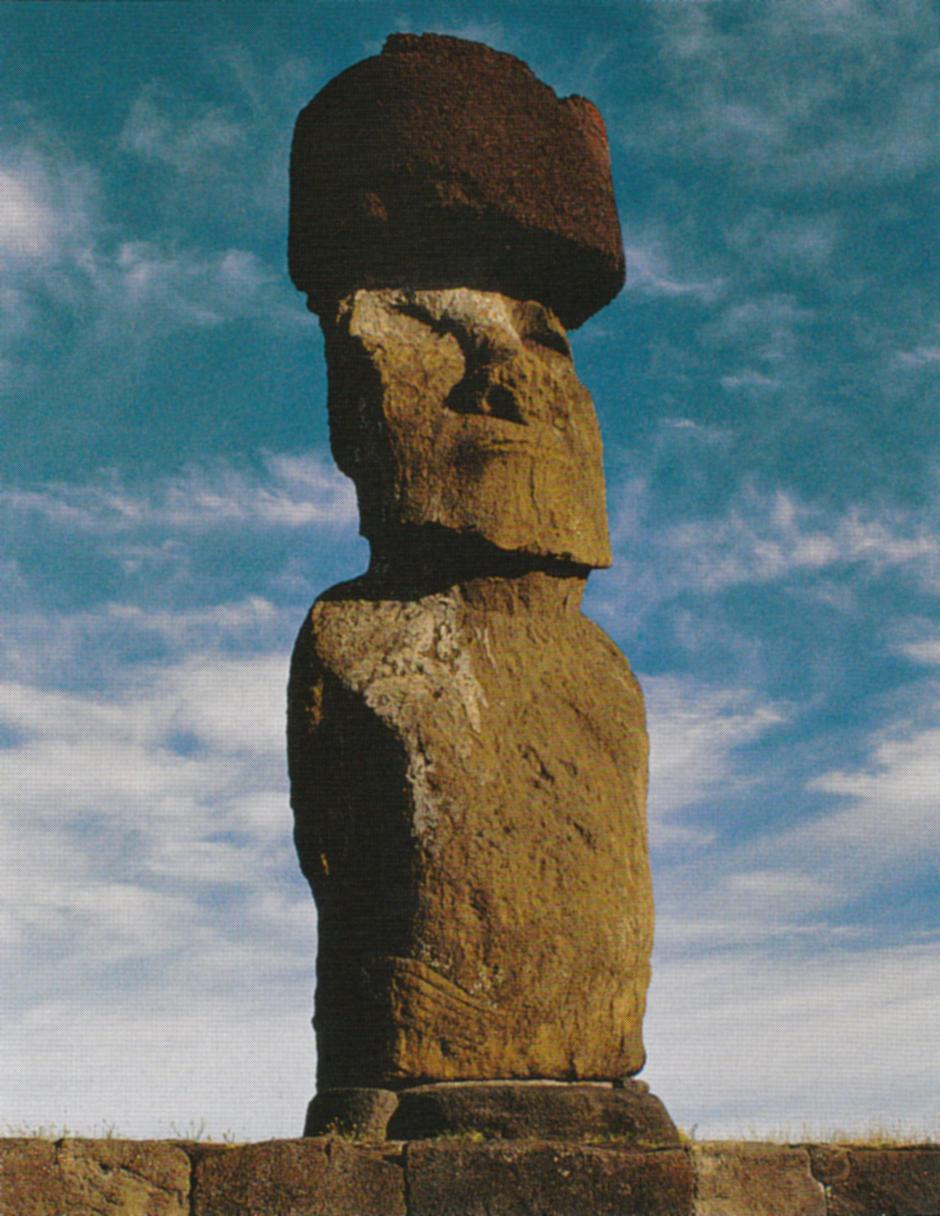

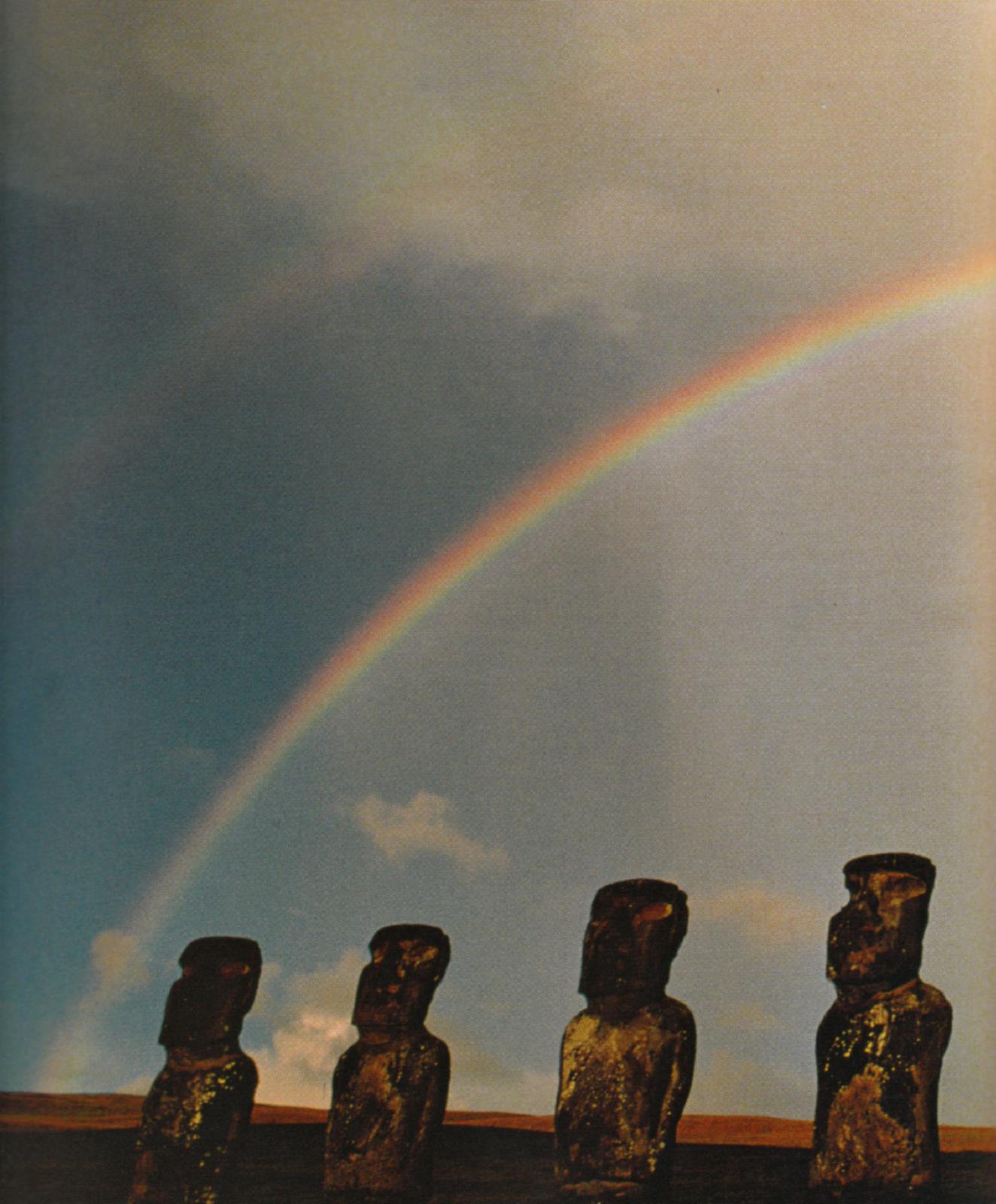

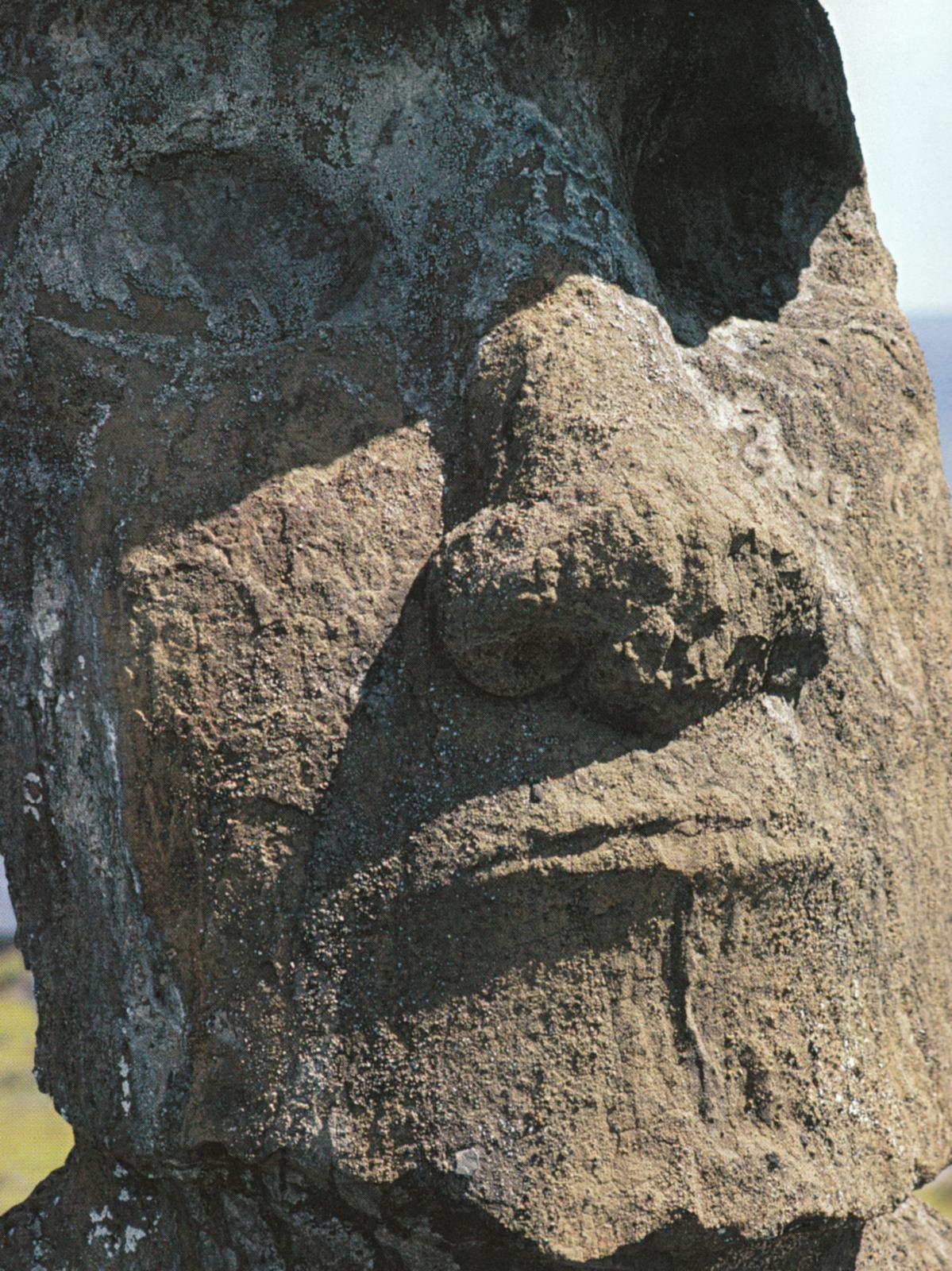

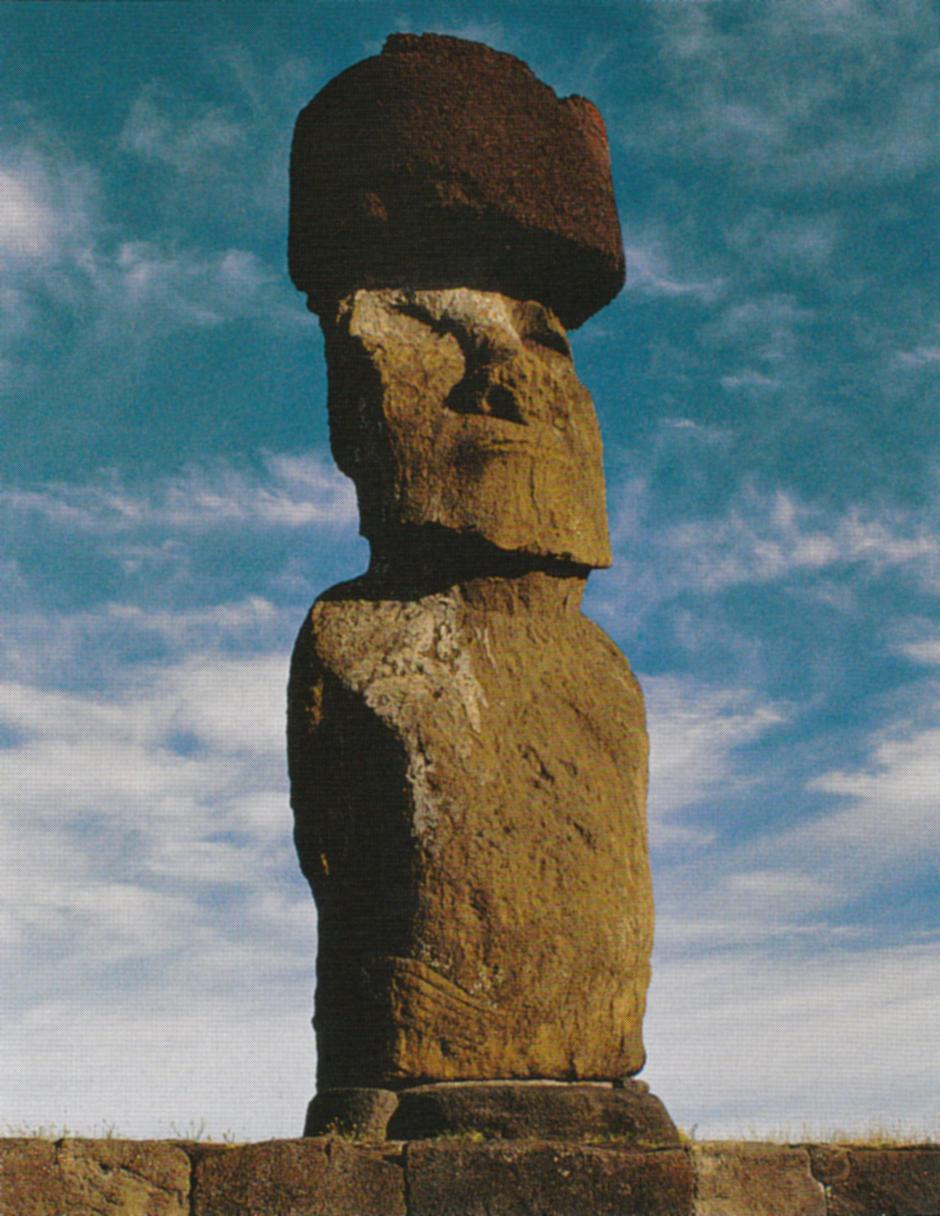

Easter Islanders of the

Pacific

Shadowed in mystery, a stony

sentinel called a moai guards the secrets of Easter Island

Its jutting chin personifying

power, a massive moai, one of nearly 900, rises

against the stark landscape

of one of the most isolated places on earth - Easter Island.

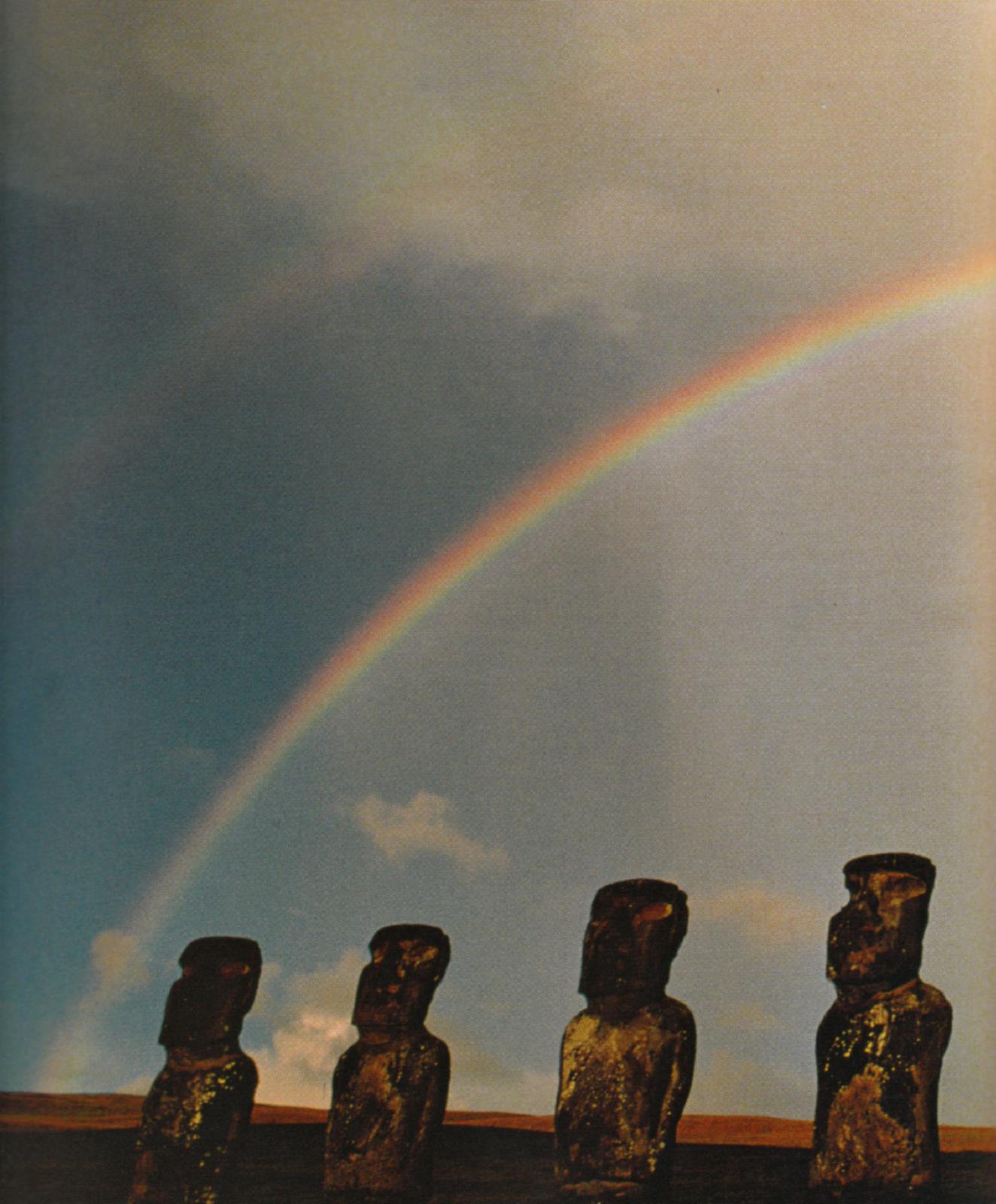

Maoi look down on an abu,

a plaza where rituals and dancing were performed

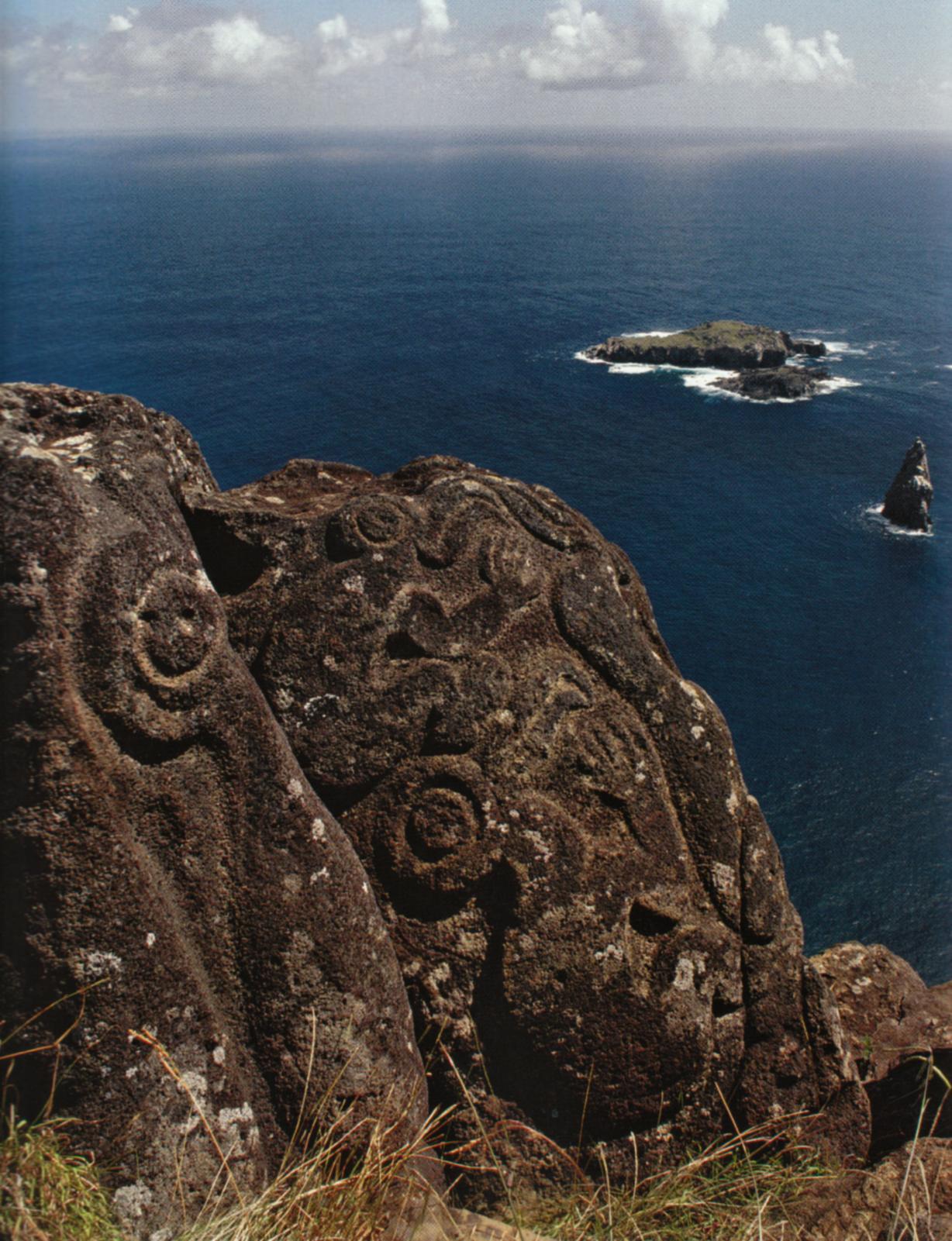

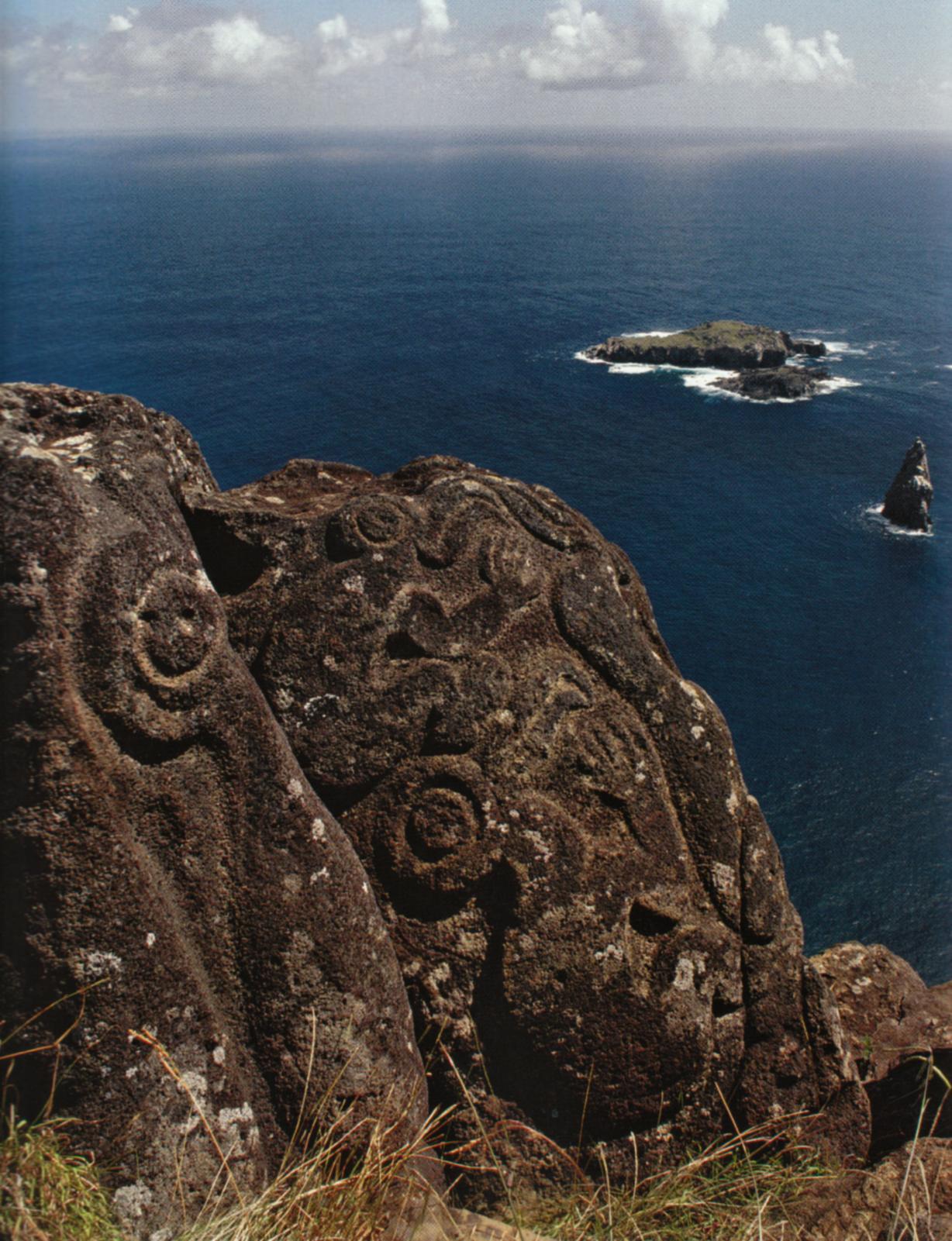

Rock art decorates the entrance

to an Easter Island cave

|

Beneath rocks carved with

the image of a creature half bird and half man, young men from

each clan would scramble

down steep cliffs for an annual swimming race to the small isle of Motu

Nui.

On the islet, they competed

to find the season's first egg from the Sooty Tern. The winner presented

the egg to his clan

representative, who assumed

the status title of Birdman, or Tangata Manu, the creator god's

surrogate on earth.

|

Like tombstones on a hill,

giant statues dot the slopes of a defunct volcano.

Easter Islanders chipped

at the volcano's soft rock with heavy stone picks to shape

the moai, leaving

some unfinished at the volcano's summit.

RECENT

EXAMPLES OF PALEOLITHIC HUNTING-GATHERING

BANDS |

The hunter-gatherers of the

Amazon rain forest in Brazil

The Awá of Brazil's

Amazon Forest

Fiona Watson /

survivalinternational.org

An Awá hunter

D Pugliese /

survivalinternational.org

The Akuntsu of Rondonia,

Brazil (on the Bolivian frontier)

soldepando.com

The Hadza people of northern

Tanzania

The Hadza people of northern

Tanzania

nature.com

The Hadza people of northern

Tanzania

in2eastafrica.net

Hadza hunters (Hazdabe) returning

from a hunt

The San or Khoisan of the

Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa

The San or Khoisan of the

Kalahari Desert (Botswana, Namibia and South Africa)

bluenred.files.wordpress.com

The San of the Kalahari

Desert

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

The San of the Kalahari

Desert

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

San hunters tracking wildebeest

in Namibia

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

The Khoi-san of the Kalahari

Desert

justfoodnow.com

"Bushmen" or San of

the Kalahari Desert

nomadtours.co.za

The San of the Kalahari

Desert

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

A San Bushman carrying his

two kids

farm4.staticlflickr.com

San women of Ghanzi in

Botswana

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

San starting a fire

Bushmen (San) tribe, Tsumkwe,

Namibia, having their meal by the fireside

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

Cagn/Kaggen is the name the

Bushmen gave their god

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

The shamans and medicine

people

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

San healing dance

kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com

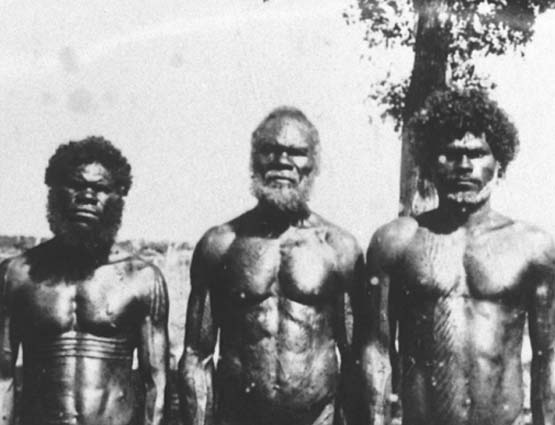

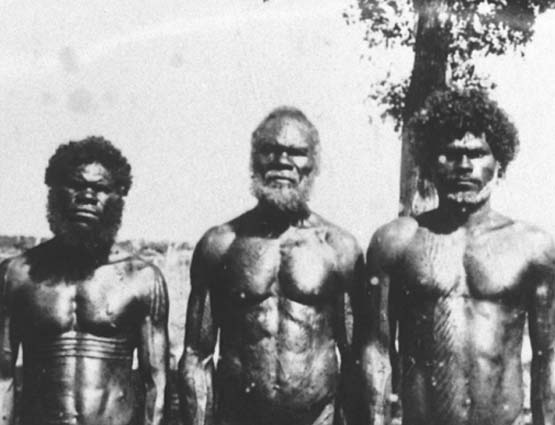

The Australian aborigine

people

Bathurst Island men - Australia,

Northern Territory - 1939

National Archives of

Australia

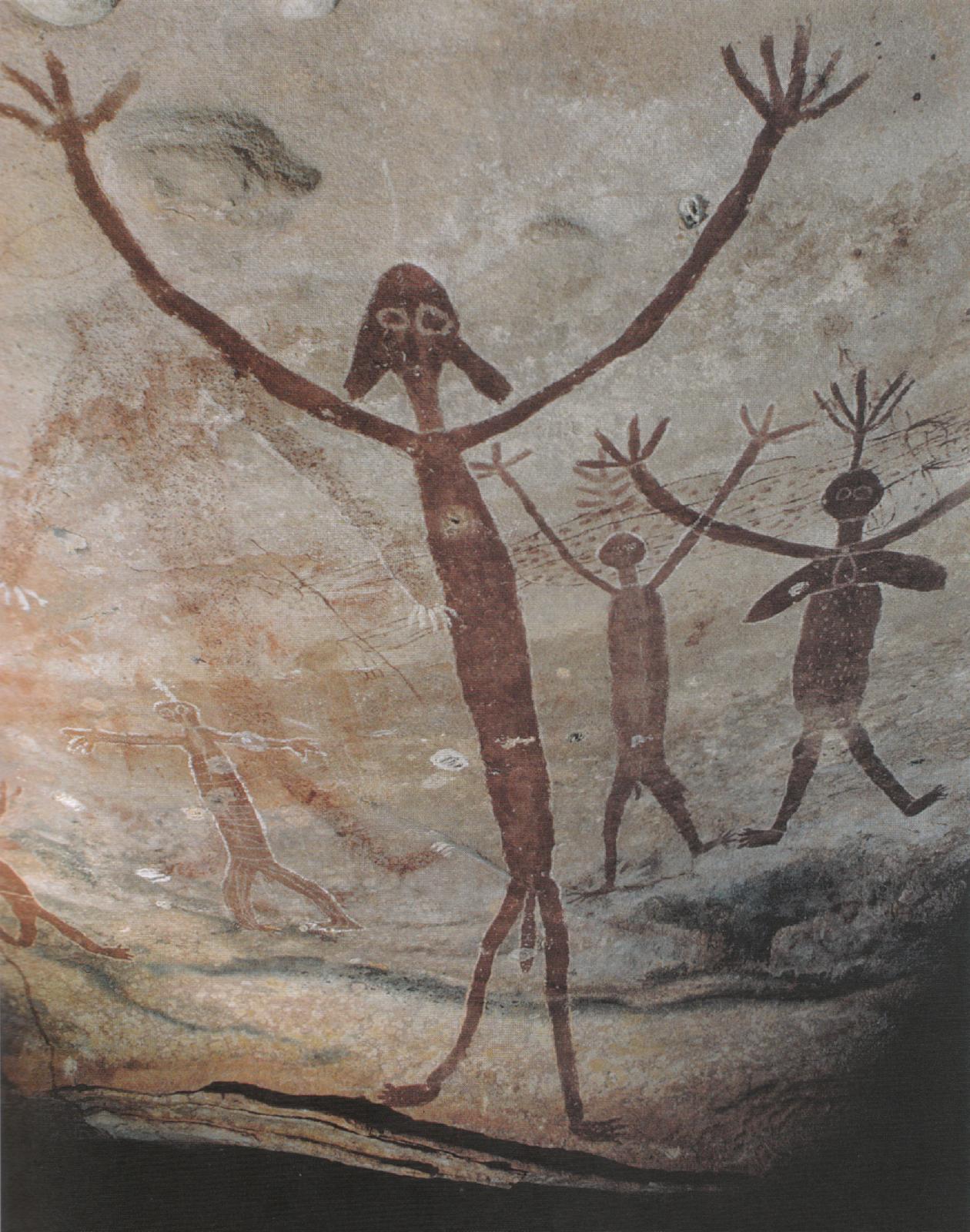

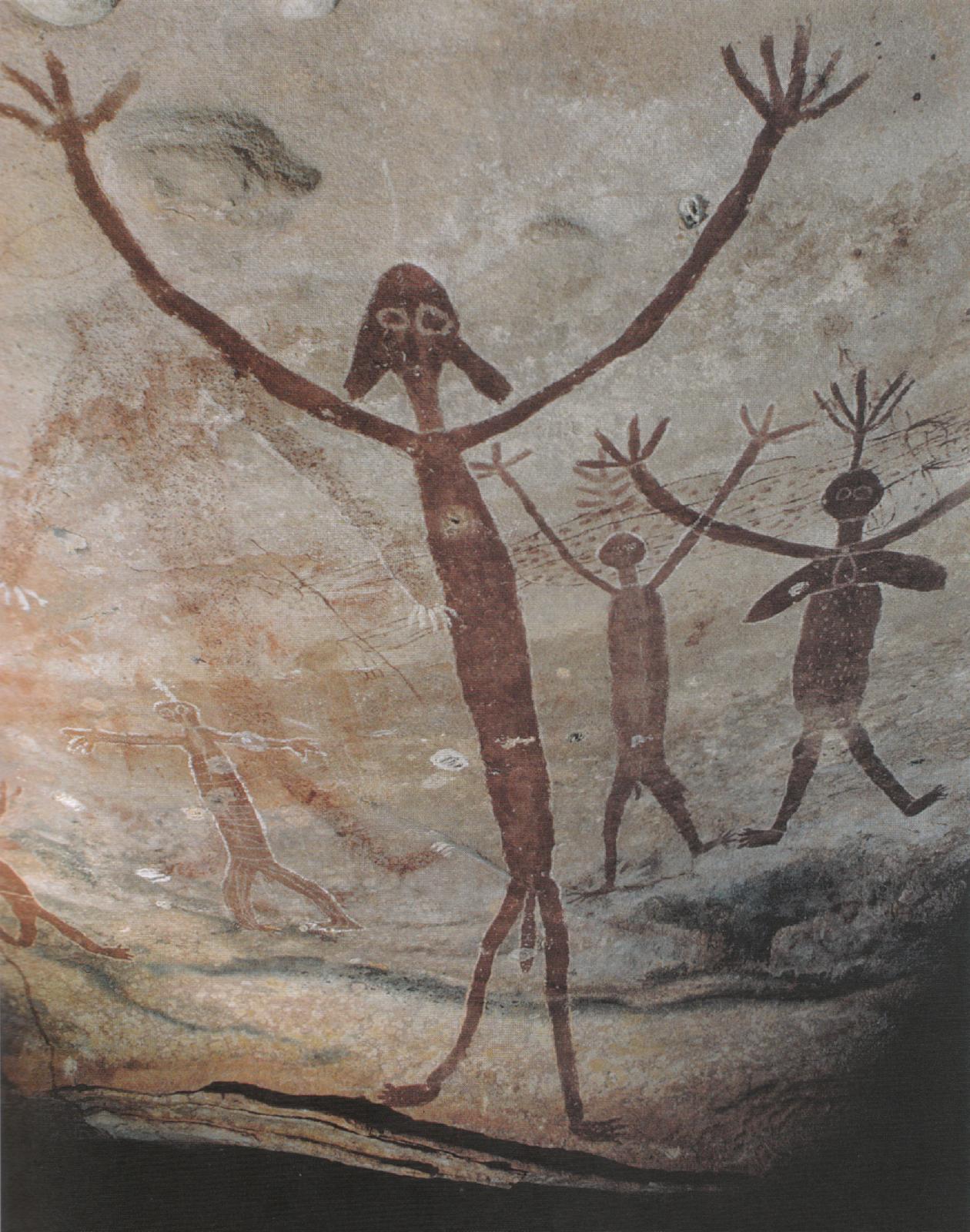

Arms raised, evil spirits

called Quinkans stand guard on cave walls in Cape York, Australia.

Australian Aborigines thought

ancestors called Wandjina came back to leave the image on rocks.

Passed over a ritual fire,

an Australian Aborigine child is baptized with pungent smoke.

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

|

The original social form: Paleolithic

The original social form: Paleolithic Paleolithic hunting-gathering bands

Paleolithic hunting-gathering bands

The paleolithic worldview or

The paleolithic worldview or Archeological finds and cave paintings

Archeological finds and cave paintings

Recent examples of paleolithic hunting-

Recent examples of paleolithic hunting-