ANCIENT CIVILIZATION

THE RISE OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATION

CONTENTS

The growth of civilization The growth of civilization

The worldview of these ancient hierarchies The worldview of these ancient hierarchies

A case study in the transition from neolithic to civilization: The Israelites A case study in the transition from neolithic to civilization: The Israelites

One of the great gifts of ancient civilization: Writing One of the great gifts of ancient civilization: Writing

The development of civilization: A chronology The development of civilization: A chronology

THE GROWTH

OF CIVILIZATION |

Sometime

in the dim past, a number of neolithic villages grew large enough to

qualify as the first true towns. Traces of such ancient towns

have been found throughout the entire Near East (such as Jericho in

modern Israel/Palestine).

But the earliest true cities, complete with an urban culture or

‘civilization’ (from the Latin, civus, meaning ‘city’), entered history

around 3000 BC along the two major river systems of the middle

East: 1) the lower reaches of the Nile in Egypt and 2) the lower

reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what was anciently called

"Mesopotamia" by the Greeks (modern Iraq).

Because of the steady source of the all-important combination of water

and sun, these settlements in Mesopotamia and Egypt flourished easily –

when they were not under attack. As the populations grew, social

organization became more important in sustaining these larger

settlements. The marshy deltas could support large populations –

provided that channels were cut, dikes were built and the marshes were

drained. Further upriver, reservoirs had to be dug to provide a

continuing water source during the dry season.

To protect this investment in real estate, fortified towns had to be

built where the people could take refuge when their lands came under

attack. Men had to be trained as soldiers to oversee the defenses

of the land. And those with special spiritual skills had to be

trained as spiritual specialists (priests), dedicated to the task of

making sure that the gods and goddesses of the land were favorably

disposed to the community's earthly endeavors. Sacrifices would

need to be carefully offered to these gods in order to appease them and

gain their heavenly support.

All this required very complex social coordination – and highly skilled political leadership.

The hierarchical principle

Hierarchy. And into this latter role stepped powerful

personalities – priest-kings who could command the respect of the

populace. At first these priest-kings may have been tribal

elders, leading kinsmen who demonstrated special administrative,

martial and spiritual talents that distinguished them from the

others. This would have been in keeping with neolithic logic.

But

eventually a new principle of social organization came to the fore

within these urban settlements, replacing the neolithic principle of

tribal kinship. This new principle is normally termed

‘hierarchy’ – a Greek term which originally applied only to a

well organized political network which governed a community of priests

(Greek: hieros, meaning ‘priest’). A hierarchy is notable by the

way it is organized in a pyramid fashion, with layers of membership

more numerous at the bottom of the pyramid, the lower orders totally

subordinate to the order immediately above them, the members smaller in

number but greater in authority as you move up the network. It is

basically a command system, mechanically efficient though relatively

impersonal – especially compared to the neolithic tribal idea of

interpersonal relations. But

eventually a new principle of social organization came to the fore

within these urban settlements, replacing the neolithic principle of

tribal kinship. This new principle is normally termed

‘hierarchy’ – a Greek term which originally applied only to a

well organized political network which governed a community of priests

(Greek: hieros, meaning ‘priest’). A hierarchy is notable by the

way it is organized in a pyramid fashion, with layers of membership

more numerous at the bottom of the pyramid, the lower orders totally

subordinate to the order immediately above them, the members smaller in

number but greater in authority as you move up the network. It is

basically a command system, mechanically efficient though relatively

impersonal – especially compared to the neolithic tribal idea of

interpersonal relations.

The most notable feature of this emerging hierarchical society is that

it was so huge that what held it together was no longer blood relations

that linked personally every member of the community. The

multitudes who made up these new huge hierarchical societies were from

many different tribes and nations. There was in fact no limit to

the numbers of different tribes and the varieties of national or ethnic

groupings that could be included in these communities. That is

because what held it together was not the social unity of the

multitudes making up the whole population, but the unity or

cohesiveness of the small group at the very top of the social

pyramid. This small group of elite were the ones responsible –

solely responsible – for maintaining the unity and integrity of the

entire social order.

The principle of serfdom or slavery.

How did this hierarchical system come about? How did it get past

the neolithic idea that society must rest only on blood ties? We

can only speculate. Perhaps it involved the insight among some of the

conquering tribes who periodically overran these river settlements that

it was foolish to put to the sword the entire population that they had

just conquered. The conquerors themselves may have had little

interest in farming the land they had just conquered. They

probably preferred to remain warriors – and let the conquered

population remain in place to raise the crops for them as slaves or

serfs. As long as the warriors alone possessed military power the

class of farmer-slaves posed no threat but instead an enormous economic

advantage – much like having large herds of animals.

While this may not have served the enserfed or enslaved farmers' sense

of dignity – it was better than being slaughtered off. In fact it

offered them a greater degree of protection, a greater degree of

security for the farmer to do his work unmolested under these

newcircumstances – for their warrior-conquerors were better able to

protect the lands than the farmers themselves.

Or – perhaps this social order simply evolved over time as a tribe

proved so successful in managing the water resources around it that the

population simply grew to monumental proportions – and one or another

clan within the tribe grew to possess the larger responsibility of

overseeing the work – until it came to constitute itself as a ruling

class. Perhaps also the usefulness of allowing unrelated tribes

to take shelter within the precincts of the growing community came to

be valued for the labor that this offered, though these immigrants

would find themselves in the community with a servant-worker status –

or even into serf or slave status, as generation after generation

became bound to the soil and the lords of the land who presided over

them. This is what seems to have happened to the Israelites or

Hebrews who took refuge in Egypt during a long drought – and eventually

became bound servants or slaves to the Egyptians.

Or perhaps it was some combination of conquest and slow development

that produced this massive hierarchical structure. But what is

certain is that around 3000 BC these huge communities began to dominate

the political scenes in Egypt and Iraq – and (perhaps that early) also

along the Indus River in Pakistan. China developed similar

systems along the Huang He (Yellow) and the Chang Jiang (Yangtze)

rivers – though centuries later than those of the Middle East.

The ruling class or caste and the priest-king or priest-emperor.

The cohesion of this whole system depended heavily on the unity and

power of the ruling class – and the particular abilities of the head of

this ruling class. At this upper level the society worked much

more like a tribal unit, in that the members of the ruling class tended

to come from a exclusive order perhaps indeed derived from a single

ancient blood line. Those born into the society of the ruling

class were the only ones entitled to the privileges of rulership.

The whole society was ultimately theirs – which they were well aware

of. But it was also their sole responsibility, this enormous

social order they had created or inherited.

At the head of this ruling class was typically a person of enormous

political and religious stature. It was not uncommon to believe

that he (or she) came from a special line of ancestors who may actually

have included one of the gods himself or herself. Thus this

individual was normally considered semi-divine, if not something of a

living god himself. Certainly this was the image projected by the

Egyptian Pharaohs. The Macedonian-Greek adventurer Alexander made

such a claim for himself. Even some of the Roman emperors

attempted to make such claims of divinity.

The Law

Over time, the power of the ruling classes was systematized through the

power of law. Legal covenants and rules of behavior

(usually given and enforced by some presiding god) now bound the rulers

and the ruled into some kind of orderly accommodation. Law proved

to be as capable as blood and custom in uniting people into effective

social units. Indeed, most highly esteemed among the rulers by

even the ruled were those ‘law-givers’ who proved able to enforce the

rule of law – and thus protect the peace – within these vast domains.

On the many carved stone (steles) located around the ancient kingdom of

Hammurabi of Babylon are found not only engraved copies of his great

Law (ca. the late 1700s BC), but usually at the top of each of these

steles is a bas-relief carving showing Hammurabi receiving these laws

from the hand of the Babylonian sun god (presumably Shamash).

This image gave huge weight to his laws, not just because they were

fair and thus worthy of being respected, but because they had the

weight of a great god behind them.

The urban center: the "city" part of civilization

The city. From a

purely material point of view, the most notable feature of civilized

society was the central role played by the city. The city was the

one place where no agriculture took place. Instead the city was

devoted to social pursuits other than farming. The city might

have been a garrison town where soldiers were housed. Or it might

have been a religious site devoted to the worship of one or another

god. It might have been the residence of the ruling

classes. It might have been a commercial center where artisans

and craftsmen gathered to manufacture and sell their wares. But

most likely it was a place where several or even all of these

activities occurred together.

Probably the heart of the city was its worship center – containing a

temple or temples housing the priests and some representational form or

other (perhaps a statue) of the god or gods they served. The

usual order of the day was receiving the sacrifices of meat or grain

brought by the pilgrim – part burned before the altar for the benefit

of the god and part set aside for consumption by the priests.

Probably somewhere nearby was the palace or palaces that housed the

civil rulers – and that opened their doors upon occasion for these

rulers to hear appeals for justice from the citizenry. And

probably nearby was the market place where pilgrims could trade some of

the extra wealth that they brought with them for just this

purpose. The market stalls with their goods on display looked out

on the main street or passageway, while behind the market stalls were

the work shops where workers toiled to produce the goods to be sold or

traded. Nearby cafes, restaurants, and hostels or hotels offered

refreshment and rest for the urban visitor – as well as a place for the

locals to take moments to relax. And of course there were homes

for those who made the city their permanent place of residence: the

aristocracy in their grand homes (probably in the neighborhood of the

palace and temple), the prosperous merchants in their private homes,

and the artisans and craftsmen – in rooms frequently in the floor above

their shops.

The city was always a buzz of activity – but especially during the high

holy seasons when important traditional festivals drew in people from

all around the realm. The cities would be decorated for the event

and parades with priests and civil notables, musicians and dancers,

masses of costumed participants, would snake through the city’s crowded

streets toward the temple where the final acts in the festival would

take place. Business would be very good. Drunken or at

least tipsy revelry would be commonplace – and so would be pickpockets

and con artists who took advantage of the frolicsome disorder.

All in a week’s fun!

The urban-rural network.

The city was the heart of a very much larger realm of city-state,

kingdom or empire. Urban life could not exist if it were not

vitally connected to the rural countryside of villages and fields where

the food supporting the whole society was produced. To support the

non-farming culture of the cities there would have to be a huge rural

culture busy at work. For each urban dweller there might have to

be ten to twenty farmers growing food – enough that the farmers could

feed not only themselves and their villages but also produce the excess

amount of food that could – through religious tithes and civil taxes –

support the urban population. The urban-rural network.

The city was the heart of a very much larger realm of city-state,

kingdom or empire. Urban life could not exist if it were not

vitally connected to the rural countryside of villages and fields where

the food supporting the whole society was produced. To support the

non-farming culture of the cities there would have to be a huge rural

culture busy at work. For each urban dweller there might have to

be ten to twenty farmers growing food – enough that the farmers could

feed not only themselves and their villages but also produce the excess

amount of food that could – through religious tithes and civil taxes –

support the urban population.

The urban-rural network could be very complex and very extensive.

A grand imperial city may have had very little or only occasional

direct contact with the rural world around it – but instead found its

life-support through lesser cities – provincial capitals actually

– that passed on to the imperial capital a part of the rural revenue

that they gathered. In this case it would be the provincial

capitals that networked directly through trade and taxes with the rural

tribal villages – and with the nomadic herdsmen who would occasionally

pitch their tents just outside these provincial cities in order to

trade meat for manufactured goods.

City-states, kingdoms and empires

With the appearance of this new principle of social organization – the

possibilities of vast and complex community life or ‘civilization’

emerged. Towns could become cities – connected economically to a

vast hinterland of small towns and rural villages. People no

longer had to be related by ‘blood-lines’ in order to cooperate

socially. Freed from the restrictions of kinship organization,

these communities could incorporate thousands, even tens and hundreds

of thousands of people into a single political unit. Thus

cities could become the centers of grand city-states, or kingdoms which

united several or more city-states, and empires which united a number

of kingdoms. The possibilities for territorial expansion were

enormous once the idea of hierarchical order was accepted.

|

THE

WORLDVIEW OF THESE ANCIENT HIERARCHIES |

|

The divine hierarchy

Just as the development of civilization produced a social and political

hierarchy here on earth – so too the worldview that accompanied this

development tended to see the heavenly world above ordered in a similar

hierarchical fashion. The heavenly world of the spirits or gods

was organized in an orderly fashion into a divine community of

carefully ranked greater and lesser gods, with the whole usually

presided over by some great super-god, as in the Aryan ‘Deus’:

Greece’s Zeus, or Rome’s Jupiter (Deus-pater) or Vedic India’s Dyaus

Pita.

The ruling classes, privileged to enjoy the special favor of the

supreme gods of heaven, nonetheless allowed the classes below them to

continue to worship their old tribal gods, lesser gods in terms of the

heavenly ranking. This helped fix the social place of the lower

classes – providing a very important emotional underpinning of the

hierarchical social order. And occasionally there were great

state occasions where even the lower social orders were allowed (or

even required) to sacrifice to the ruling or supreme state god or gods

of the ruling class. This provided a proper sense of order to

life in the community.

It was not that the heavens mirrored the earthly hierarchy – but rather

the reverse. The earthly hierarchy was always considered to be a

mirroring of the heavenly hierarchy. It was the heavenly

hierarchy that gave rise to the hierarchical social order on

earth. It was the very top gods that had called the earthly

rulers to their governing positions and who sanctioned or supported

their rule from above. Thus behind the might of the rulers or the

ruling class stood the power of the gods in heaven. Thus to

contest the right of the ruling classes to rule was to challenge the

entire heavenly scheme of things – something that no one would likely

be willing to do under any circumstances. To challenge the social

order on earth was to challenge the gods themselves.

The Bible tells the story of one occasion when just such a challenge

took place. This was when Moses went before the Egyptian Pharaoh

to demand the release of the Hebrew slaves from their bondage –

supposedly to allow them to leave Egypt in order to worship Moses’ god

YHWH in the eastern desert. Needless to say the Pharaoh was

unimpressed with Moses’ demand – unimpressed until Moses was able to

demonstrate that his god was more powerful than the Egyptian gods and

their Egyptian priests. But this took a number of power struggles

between Moses and the Egyptian priests – and between his god and

theirs. But finally the death of all the firstborn males of the

Egyptians (and the immunity of the Hebrews’ sons from the same fate as

the angels of death passed over the Hebrew families) was such an

overwhelming demonstration of YHWH’s power that the Hebrews were

finally released (although not without one last instance of Pharaoh

changing his mind – but again, to no avail). YHWH had amply

demonstrated that he was the Supreme God (El Shaddai); there were no

other gods above him, before him, or even equal to him. [This was

something however that the Hebrews or Israelites themselves were often

to forget.]

|

>A

CASE STUDY IN THE TRANSITION FROM NEOLITHIC SOCIETY TO ANCIENT CIVILIZATION:

THE ISRAELITES |

|

The neolithic tribal confederacy

The most complete account we possess today of the dynamic of a society

shifting from neolithic life into full-blown traditional civilization,

complete with urban capital, king and temple, is found in great detail

in the Hebrew Bible. The neolithic foundations of the Hebrews or

Israelites take definite political or social shape with the great

founding father, Abraham. He and his offspring were nomadic

herders rather than agricultural villagers – operating in the strip of

land between the lower portions of the eastern Mediterranean and the

Jordan River. Abraham’s exploits were so notable that he became

the starting point of a generational narrative that eventually gave

identity to the nation Israel. Twelve of his grandsons or

great-grandsons themselves achieved sufficient distinction that they

passed their names on to the twelve tribes that ultimately made up the

nation as a whole.

The story goes into something of a huge hiatus when these tribes were

driven by drought into Egypt – and into slavery there – where over the

next few centuries they nearly lost their identity. Eventually

Moses was called to rescue them from their plight in Egypt (1200 BC?) -

and restore them as YHWH’s specially chosen people. Furthermore

he was to bring them back to the land that had once been Abraham’s

nomadic legacy – now inhabited by the agricultural Canaanites.

The relationship between the settled Canaanites and the not-so-settled

Hebrews (Israelites) was typically characterized by warfare.

Gradually the Israelites settled in on the land and themselves became

farmers. But they too were troubled by surrounding nomadic tribes

– and found themselves having to fend off these troublesome neighbors,

not always successfully.

At this point Israel was a loosely confederated community of tribes

without any specific leadership as a whole – except in emergency

situations when one or another tribesman, upon the call of YHWH, would

be elevated to leadership to take command of a joint effort of the

Israelites tribes to rid themselves of the immediate danger, typically

the neighboring Amorites – though later typically the invading

Philistines. Once the immediate danger was past the tribes

reverted to their former loose political relationship. Their

spirit of thanksgiving to YHWH for the deliverance of Israel would also

revert to a kind of looseness, especially with subsequent generations

for whom such saving events were merely stories and not actual

realities.

A social or political transition began shortly before 1000 BC when

Israel had become somewhat more united under YHWH’s prophet

Samuel. Israel was beginning to look and act more and more like

the larger city-states or empires growing up around them in Syria,

Egypt and Mesopotamia (Iraq). Finally, toward the later days of

Samuel’s religious presidency the Israelites demanded of him that he

actually select or anoint them a king. Israel wanted to be more

than just a neolithic confederacy. It wanted to be reconstituted

as a true kingdom. Samuel relayed to them YHWH’s warning of what

this was going to mean to them: greater national status perhaps, but

the loss of a large amount of personal freedom at the same time.

But it seems that this was what Israel wanted. And so Samuel was

led to anoint Saul as Israel’s first king.

The Davidic Kingship

Saul, as it turned out, proved not to be the ideal king the people

hoped for. But his successor, David, was (though not without

personal blemishes of his own). The Israelites made much of the

idea that David was a man of YHWH’s own heart – ruling Israel in and

through YHWH’s very power. He successfully united the tribes into

something indeed resembling a strong, unified nation. When the

Jebusite (likely an Amorite subtribe) town of Jerusalem was captured by

David, Israel also now found itself in possession of a capital

city. The key religious articles of the YHWHist religion were

moved from Bethel in the north to the new capital at Jerusalem.

David wanted to build in Jerusalem a permanent temple to replace the

tent-like structure of the old YHWHist holy shrine which housed all

these religious articles – but received instructions from YHWH that

this was not his call to do so. Nonetheless a palace was erected

for David – and Jerusalem began to take on the look of a noble capital

city.

It was under his successor, Solomon, that the full transition to

civilized status occurred for the Israelites. Solomon not only

built a magnificent temple to YHWH – he apparently also erected temples

to the gods of the many wives he took on as he expanded – through

marriage or conquest or both – the reach of the Israelite

kingdom. This produced mixed emotions in Israel. The

YHWHist purists were shocked at his loose religious loyalties – though

the general populace seemed to approve of the great material success of

his diplomacy and military ventures.

But this success did not long outlive Solomon - and his grand kingdom

split into two separate and often warring sub-kingdoms of Israel and

Judah with the next generation after him. And from then on the

kings of these two Israelite kingdoms tended to be considerably less

than brilliant – at least according to the YHWHist accounts in the

Hebrew Bible. Foolish diplomacy and unwise decisions to go to war

served only to diminish the power of the two kingdoms over time.

Eventually in the late 700s BC the Assyrians carried off in defeat and

into oblivion the northern tribes of the kingdom of Israel, leaving

only the southern Israelite tribe of Judah to survive. But a

little over a century later Judah too suffered something of a similar

fate (though not the oblivion portion) when the key leadership of Judah

was carried off to captivity in Babylon – and the temple of YHWH was

leveled. Thus the Davidic kingdom of Israel came to an abysmal

end.

|

ONE

OF THE GREAT GIFTS OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATION: WRITING |

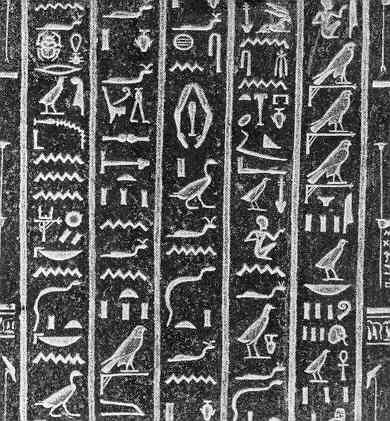

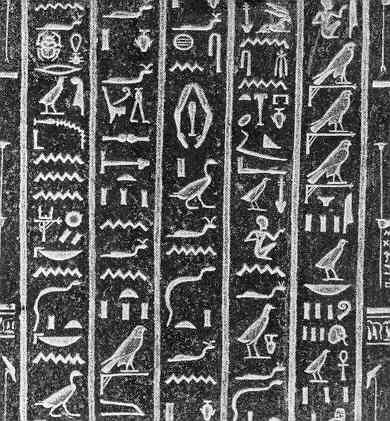

Egyptian Pictographic Writing

Egyptian Museum

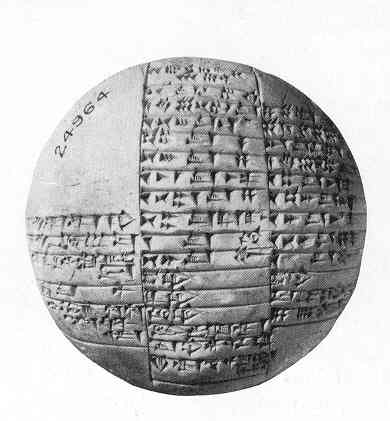

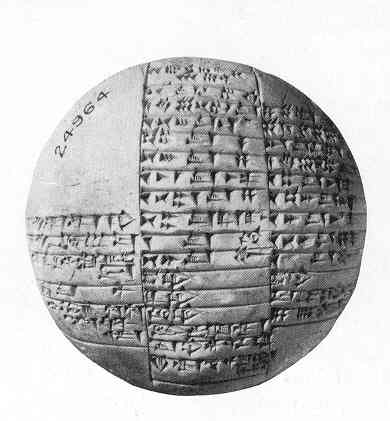

Sumerian Cuneiform tablet

British Museum

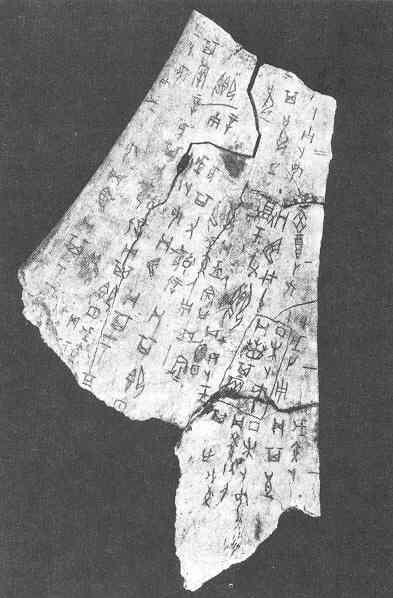

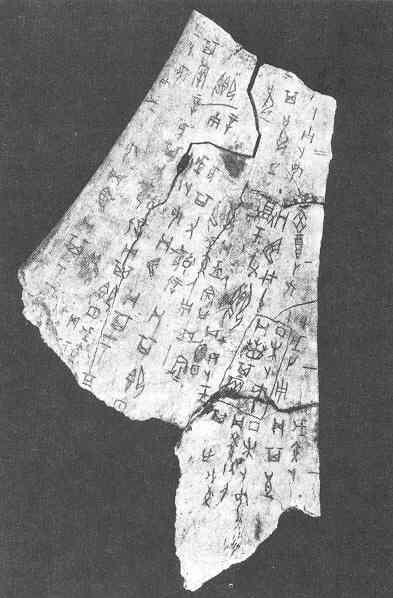

Chinese Oracle Bone (ancient

writing scratched onto an ox scapula) -

from the latter part of

the Shang Dynasty (ca. 1200-1050 BC?)

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CIVILIZATION: A CHRONOLOGY |

|

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CIVILIZATION:

A

CHRONOLOGY

|

|

|

| 13,000 BC |

Retreat of the last

ice age begins the Holocene (recent) Epoch |

| 10,000

BC |

Flint knives used in

Palestine in reaping wild grains |

| 9000

BC |

End of the last Ice

Age; domesticated sheep in the North Tigris valley |

| 7500

BC |

Fortified Jericho settlement

– cultivated cereals |

| 7000

BC |

Fertility cult in Asia

Minor (Turkey) indicates use of domesticated cattle

Earliest pottery invented in the

Middle East |

| 6500

BC |

Copper in Asia Minor

– used for ornamentation |

| 5000

BC |

Copper in Mesopotamia

(land of the "two rivers" in modern Iraq)

Sumerians settle lower

Mesopotamia |

| 3700

BC |

Rise of the city-states

in Sumer: Ur, Uruk, Lagash, Kish

Wheel-made pottery, sailboats, animal-drawn

plows

Bronze in use in both Sumer and

Egypt |

| 3500

BC |

Two separate kingdoms

in Egypt along the lower and upper Nile |

| 3200

BC |

Sumerian cuneiform writing

used to keep royal records |

| 3100

BC |

Hieroglyphics (pictorial

writing) in Egypt |

| 3000

BC |

The rise of the unified

Egyptian state governing vast reaches of the Nile;

Wheeled vehicle used in

Sumer |

| 2550

BC |

Beginning of pyramid

building in Egypt |

| 2360

BC |

Sargon the Great of

Akkad (central Mesopotamia) rules the bulk of the Middle East |

| 2000

BC |

The beginning of the

Aryan migrations from southern Russia:

to India (Hindus),

to Asia Minor (Hittites) and to Greece (Myceneans)

somewhat later to Central

Europe (the Celts)

Possibly the time when Semitic migrations

from Arabia occur

Abraham migrates from

Ur to Palestine?

The rise of the Greek-speaking Minoan

state in Crete; palace at Knossos

The powerful Middle Kingdom of

Egypt

Sumer in decline |

| 1800

BC |

Hammurabi: law-giver

and ruler of Babylonian empire (based in central

Mesopotamia) |

| 1700

BC |

The Hittite Empire emerges

in central Asia Minor (modern Turkey);

Hittites use the new

secret metal: iron

The Semitic Hyksos overrun

Egypt

Hebrews (Jacob and Joseph and his

brothers) settle in Egypt – perhaps under

Hyksos

protection |

| 1550

BC |

Egyptian power

restored

The Hyksos expelled from new Egyptian

Empire (Hebrews enslaved?) |

| 1450

BC |

Cretan (Minoan) civilization

collapses – probably as a result of devastating

volcanic or earthquake

activity |

| 1390

BC |

The "Golden Age" of

Egypt begins under pharaoh Amenhotep III |

| 1350

BC |

Akhenaten, son of Amenhotep

III, tries to establish monotheism in Egypt |

| 1275

BC |

Ramesses (or Ramses)

II the Great – pharaoh of Egypt

Moses leads the Hebrews from

Egypt?

Aryan Medes and Persians invading

Iran

Assyrians from the north extending

their power over Mesopotamia |

| 1250

BC |

Troy besieged by the

Greeks |

| 1200

BC |

The period of the Israelite

Judges begins

The Hittite empire

collapses |

| 1100

BC |

Beginning of the Dorian

and Ionian invasions of Greece |

| 1070

BC |

The Philistines conquer

Israel and settle the coastal plains |

| 1000

BC |

David rules a united

Israel from Jerusalem

Germanic (Aryan) tribes migrate

to the Rhine River |

| 961

BC |

Solomon succeeds his

father David to the throne of Israel |

| 922

BC |

Upon death of Solomon,

Israel splits into two kingdoms: Israel (Northern) and

Judah

(Southern) |

| 850

BC |

Assyrian power in the

ascendancy again: attacks Israel (Northern kingdom) |

| 800

BC |

Traditional date for

the writing of Homer's Epic poems: the Iliad and the

Odyssey (but

modern scholars place the date closer to 700 BC)

Aryans establishing the Hindu caste

system over the Indian population |

| 750

BC |

Israel (Northern Kingdom)

at height of prosperity under Jeroboam II

The traditional date for the founding

of Rome by Romulus and Remus |

| 722

BC |

Sargon II of Assyria

overruns Israel (the Northern Kingdom); takes 27,000 Israelites captive;

destroys Israel |

| 650

BC |

Beginning of period

of rule of Greek city-states by tyrants (dictators) |

| 626-609

BC |

Wars of independence

by subject nations of the Assyrians; Assyria collapses |

| 605

BC |

Rise of Babylonian power

under Nebuchadnezzar II (to 561 BC) |

| 594

BC |

Solon in Athens reforms

the severe laws of Draco, setting up democratic rule |

| 586

BC |

Nebuchadnezzar II sacks

Jerusalem and carries the population of Judah into captivity |

| 559

- 529 BC |

Cyrus II, the Great,

king of Persia; overruns Asia Minor (546) and Babylon

(539); allows

the Jews to return to Judah, ending the "Babylonian Captivity"

(538) |

| 500

BC |

Persia rules from Egypt

in the West to the Indus River in the East (Darius I,

king: 521-

486).

Athens has confirmed its commitment

to democracy--against a Spartan effort

to restore aristocratic

rule in Athens (507)

Etruscans are at the height of their

power in northern Italy

But Rome is under Republican government

and in control of the whole of

Latium (west-central

Italy) |

|

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

|

The growth of civilization

The growth of civilization

The worldview of these ancient hierarchies

The worldview of these ancient hierarchies

A case study in the transition from neolithic to civilization: The Israelites

A case study in the transition from neolithic to civilization: The Israelites

One of the great gifts of ancient civilization: Writing

One of the great gifts of ancient civilization: Writing

The development of civilization: A chronology

The development of civilization: A chronology