|

|

CHAPTER XIX A FRESH EFFORT AND AN ARMY CHAPLAIN

Spearman's Hill: February 4, 1900

The first gleams of daylight crept underneath the waggon, and the sleepers, closely packed for shelter from the rain showers, awoke. Those who live under the conditions of a civilised city, who lie abed till nine and ten of the clock in artificially darkened rooms, gain luxury at the expense of joy. But the soldier, who fares simply, sleeps soundly, and rises with the morning star, wakes in an elation of body and spirit without an effort and with scarcely a yawn. There is no more delicious moment in the day than this, when we light the fire and, while the kettle boils, watch the dark shadows of the hills take form, perspective, and finally colour, knowing that there is another whole day begun, bright with chance and interest, and free from all cares. All cares—for who can be worried about the little matters of humdrum life when he may be dead before the night? Such a one was with us yesterday—see, there is a spare mug for coffee in the mess—but now gone for ever. And so it may be with us to-morrow. What does it matter that this or that is misunderstood or perverted; that So-and-so is envious and spiteful; that heavy difficulties obstruct the larger schemes of life, clogging nimble aspiration with the mud of matters of fact? Here life itself, life at its best and healthiest, awaits the caprice of the bullet. Let us see the development of the day. All else may stand over, perhaps for ever. Existence is never so sweet as when it is at hazard. The bright butterfly flutters in the sunshine, the expression of the philosophy of Omar Khayyám, without the potations.

But we awoke on the morning of the 25th in most gloomy spirits. I had seen the evacuation of Spion Kop during the night, and I did not doubt that it would be followed by the abandonment of all efforts to turn the Boer left from the passages of the Tugela at and near Trichardt's Drift. Nor were these forebodings wrong. Before the sun was fairly risen orders arrived, 'All baggage to move east of Venter's Spruit immediately. Troops to be ready to turn out at thirty minutes' notice.' General retreat, that was their meaning. Buller was withdrawing his train as a preliminary to disengaging, if he could, the fighting brigades, and retiring across the river. Buller! So it was no longer Warren! The Commander-in-Chief had arrived, in the hour of misfortune, to take all responsibility for what had befallen the army, to extricate it, if possible, from its position of peril, to encourage the soldiers, now a second time defeated without being beaten, to bear the disappointment. Everyone knows how all this, that looked so difficult, was successfully accomplished.

The army was irritated by the feeling that it had made sacrifices for nothing. It was puzzled and disappointed by failure which it did not admit nor understand. The enemy were flushed with success. The opposing lines in many places were scarcely a thousand yards apart. As the infantry retired the enemy would have commanding ground from which to assail them at every point. Behind flowed the Tugela, a deep, rapid, only occasionally fordable river, eighty-five yards broad, with precipitous banks. We all prepared ourselves for a bloody and even disastrous rearguard action. But now, I repeat, when things had come to this pass, Buller took personal command. He arrived on the field calm, cheerful, inscrutable as ever, rode hither and thither with a weary staff and a huge notebook, gripped the whole business in his strong hands, and so shook it into shape that we crossed the river in safety, comfort, and good order, with most remarkable mechanical precision, and without the loss of a single man or a pound of stores.

The fighting troops stood fast for two days, while the train of waggons streamed back over the bridges and parked in huge black squares on the southern bank. Then, on the night of the 26th, the retreat began. It was pitch dark, and a driving rain veiled all lights. The ground was broken. The enemy near. It is scarcely possible to imagine a more difficult operation. But it was performed with amazing ease. Buller himself—not Buller by proxy or Buller at the end of a heliograph—Buller himself managed it. He was the man who gave orders, the man whom the soldiers looked to. He had already transported his train. At dusk he passed the Royals over the ford. By ten o'clock all his cavalry and guns were across the pontoon bridges. At ten he began disengaging his infantry, and by daylight the army stood in order on the southern bank. While the sappers began to take the pontoon bridges to pieces the Boers, who must have been astonished by the unusual rapidity of the movement, fired their first shell at the crossing. We were over the river none too soon.

A successful retreat is a poor thing for a relieving army to boast of when their gallant friends are hard pressed and worn out. But this withdrawal showed that this force possesses both a leader and machinery of organisation, and it is this, and this alone, that has preserved our confidence. We believe that Buller gauged the capacity of one subordinate at Colenso, of another at Spion Kop, and that now he will do things himself, as he was meant to do. I know not why he has waited so long. Probably some pedantic principle of military etiquette: 'Commander-in-Chief should occupy a central position; turning movements should be directed by subordinates.' But the army believes that this is all over now, and that for the future Buller will trust no one but himself in great matters; and it is because they believe this that the soldiers are looking forward with confidence and eagerness to the third and last attempt—for the sands at Ladysmith have run down very low—to shatter the Boer lines.

We have waited a week in the camp behind Spearman's Hill. The General has addressed the troops himself. He has promised that we shall be in Ladysmith soon. To replace the sixteen hundred killed and wounded in the late actions, drafts of twenty-four hundred men have arrived. A mountain battery, A Battery R.H.A., and two great fortress guns have strengthened the artillery. Two squadrons of the 14th Hussars have been added to the cavalry, so that we are actually to-day numerically stronger by more than a thousand men than when we fought at Spion Kop, while the Boers are at least five hundred weaker—attrition versus recuperation. Everyone has been well fed, reinforced and inspirited, and all are prepared for a supreme effort, in which we shall either reach Ladysmith or be flung back truly beaten with a loss of six or seven thousand men.

I will not try to foreshadow the line of attack, though certain movements appear to indicate where it will be directed. But it is generally believed that we fight to-morrow at dawn, and as I write this letter seventy guns are drawing up in line on the hills to open the preparatory bombardment.

It is a solemn Sunday, and the camp, with its white tents looking snug and peaceful in the sunlight, holds its breath that the beating of its heart may not be heard. On such a day as this the services of religion would appeal with passionate force to thousands. I attended a church parade this morning. What a chance this was for a man of great soul who feared God! On every side were drawn up deep masses of soldiery, rank behind rank—perhaps, in all, five thousand. In the hollow square stood the General, the man on whom everything depended. All around were men who within the week had been face to face with Death, and were going to face him again in a few hours. Life seemed very precarious, in spite of the sunlit landscape. What was it all for? What was the good of human effort? How should it befall a man who died in a quarrel he did not understand? All the anxious questionings of weak spirits. It was one of those occasions when a fine preacher might have given comfort and strength where both were sorely needed, and have printed on many minds a permanent impression. The bridegroom Opportunity had come. But the Church had her lamp untrimmed. A chaplain with a raucous voice discoursed on the details of 'The siege and surrender of Jericho.' The soldiers froze into apathy, and after a while the formal perfunctory service reached its welcome conclusion.

As I marched home an officer said to me: 'Why is it, when the Church spends so much on missionary work among heathens, she does not take the trouble to send good men to preach in time of war? The medical profession is represented by some of its greatest exponents. Why are men's wounded souls left to the care of a village practitioner?' Nor could I answer; but I remembered the venerable figure and noble character of Father Brindle in the River War, and wondered whether Rome was again seizing the opportunity which Canterbury disdained—the opportunity of telling the glad tidings to soldiers about to die.

CHAPTER XX

THE COMBAT OF VAAL KRANTZ

General Buller's Headquarters: February 9, 1900.

During the ten days that passed peacefully after the British retreat from the positions beyond Trichardt's Drift, Sir Redvers Buller's force was strengthened by the arrival of a battery of Horse Artillery, two powerful siege guns, two squadrons of the 14th Hussars, and drafts for the Infantry battalions, amounting to 2,400 men. Thus not only was the loss of 1,600 men in the five days' fighting round Spion Kop made good, but the army was actually a thousand stronger than before its repulse. Good and plentiful rations of meat and vegetables were given to the troops, and their spirits were restored by the General's public declaration that he had discovered the key to the enemy's position, and the promise that within a week from the beginning of the impending operation Ladysmith should be relieved. The account of the straits to which the gallant garrison was now reduced by famine, disease, and war increased the earnest desire of officers and men to engage the enemy and, even at the greatest price, to break his lines. In spite of the various inexplicable features which the actions of Colenso and Spion Kop presented, the confidence of the army in Sir Redvers Buller was still firm, and the knowledge that he himself would personally direct the operations, instead of leaving their conduct to a divisional commander, gave general satisfaction and relief.

On the afternoon of February 4 the superior officers were made acquainted with the outlines of the plan of action to be followed. The reader will, perhaps, remember the description in a former letter of the Boer position before Potgieter's and Trichardt's Drift as a horizontal note of interrogation, of which Spion Kop formed the centre angle—/\. The fighting of the previous week had been directed towards the straight line, and on the angle. The new operation was aimed at the curve. The general scheme was to seize the hills which formed the left of the enemy's position and roll him up from left to right. It was known that the Boers were massed mainly in their central camp behind Spion Kop, and that, as no demonstration was intended against the position in front of Trichardt's Drift, their whole force would be occupying the curve and guarding its right flank. The details of the plan were well conceived.

The battle would begin by a demonstration against the Brakfontein position, which the Boers had fortified by four tiers of trenches, with bombproof casemates, barbed wire entanglements, and a line of redoubts, so that it was obviously too strong to be carried frontally. This demonstration would be made by Wynne's Brigade (formerly Woodgate's), supported by six batteries of Artillery, the Howitzer Battery, and the two 4.7-inch naval guns. These troops crossed the river by the pontoon bridge at Potgieter's on the 3rd and 4th, relieving Lyttelton's Brigade which had been in occupation of the advanced position on the low kopjes.

A new pontoon bridge was thrown at the angle of the river a mile below Potgieter's, the purpose of which seemed to be to enable the frontal attack to be fully supported. While the Artillery preparation of the advance against Brakfontein and Wynne's advance were going on, Clery's Division (consisting of Hart's Brigade and Hildyard's) and Lyttelton's Brigade were to mass near the new pontoon bridge (No. 2), as if about to support the frontal movement. When the bombardment had been in progress for two hours these three brigades were to move, not towards the Brakfontein position, but eastwards to Munger's Drift, throw a pontoon bridge covered first by one battery of Field Artillery withdrawn from the demonstration, secondly by the fire of guns which had been dragged to the summit of Swartkop, and which formed a powerful battery of fourteen pieces, viz., six 12-pounder long range naval guns, two 15-pounder guns of the 64th Field Battery, six 9-pounder mountain guns, and lastly by the two 50-pounder siege guns. As soon as the bridge was complete Lyttelton's Brigade would cross, and, ignoring the fire from the Boer left, extended along the Doornkloof heights, attack the Vaal Krantz ridge, which formed the left of the horseshoe curve around the debouches of Potgieter's. This attack was to be covered on its right by the guns already specified on Swartkop and the 64th Field Battery, and prepared by the six artillery batteries employed in the demonstration, which were to withdraw one by one at intervals of ten minutes, cross No. 2 pontoon bridge, and take up new positions opposite to the Vaal Krantz ridge.

If and when Vaal Krantz was captured all six batteries were to move across No. 3 bridge and take up positions on the hill, whence they could prepare and support the further advance of Clery's Division, which, having crossed, was to move past Vaal Krantz, pivot to the left on it, and attack the Brakfontein position from its left flank. The 1st Cavalry Brigade under Burn-Murdoch (Royals, 13th and 14th Hussars, and A Battery R.H.A.) would also cross and run the gauntlet of Doornkloof and break out on to the plateau beyond Clery's Division. The 2nd Cavalry Brigade (South African Light Horse, Composite Regiment, Thorneycroft's, and Bethune's Mounted Infantry, and the Colt Battery) were to guard the right and rear of the attacking troops from any attack coming from Doornkloof. Wynne was to co-operate as opportunity offered. Talbot Coke was to remain in reserve. Such was the plan, and it seemed to all who heard it good and clear. It gave scope to the whole force, and seemed to offer all the conditions for a decisive trial of strength between the two armies.

On Sunday afternoon the Infantry Brigades began to move to their respective positions, and at daylight on the 5th the Cavalry Division broke its camp behind spearman's. At nine minutes past seven he bombardment of the Brakfontein position began, and by half-past seven all the Artillery except the Swartkop guns were firing in a leisurely fashion at the Boer redoubts and entrenchments. At the same time Wynne's Brigade moved forward in dispersed formation towards the enemy, and the Cavalry began to defile across the front and to mass near the three Infantry Brigades collected near No. 2 pontoon bridge. For some time the Boers made no reply, but at about ten o'clock their Vickers-Maxim opened on the batteries firing from the Potgieter's plain, and the fire gradually increased as other guns, some of great range, joined in, until the Artillery was sharply engaged in an unsatisfactory duel—fifty guns exposed in the open against six or seven guns concealed and impossible to find. The Boer shells struck all along the advanced batteries, bursting between the guns, throwing up huge fountains of dust and smoke, and covering the gunners at times completely from view. Shrapnel shells were also flung from both flanks and ripped the dusty plain with their scattering bullets. But the Artillery stood to their work like men, and though they apparently produced no impression on the Boer guns, did not suffer as severely as might have been expected, losing no more than fifteen officers and men altogether. At intervals of ten minutes the batteries withdrew in beautiful order and ceremony and defiled across the second pontoon bridge. Meanwhile Wynne's Brigade had advanced to within twelve hundred yards of the Brakfontein position and retired, drawing the enemy's heavy fire; the three brigades under Clery had moved to the right near Munger's Drift; the Cavalry were massed in the hollows at the foot of Swartkop; and the Engineers had constructed the third pontoon bridge, performing their business with excellent method and despatch under a sharp fire from Boer skirmishers and a Maxim.

The six batteries and the howitzers now took up positions opposite Vaal Krantz, and seventy guns began to shell this ridge in regular preparation and to reply to three Boer guns which had now opened from Doornkloof and our extreme right. A loud and crashing cannonade developed. At midday the Durham Light Infantry of Lyttelton's Brigade crossed the third pontoon bridge and advanced briskly along the opposite bank on the Vaal Krantz ridge. They were supported by the 3rd King's Royal Rifles, and behind these the other two battalions of the Brigade strengthened the attack. The troops moved across the open in fine style, paying no attention to the enemy's guns on Doornkloof, which burst their shrapnel at seven thousand yards (shrapnel at seven thousand yards!) with remarkable accuracy. In an hour the leading companies had reached the foot of the ridge, and the active riflemen could be seen clambering swiftly up. As the advance continued one of the Boer Vickers-Maxim guns which was posted in rear of Vaal Krantz found it wise to retire and galloped off unscathed through a tremendous fire from our artillery: a most wonderful escape.

The Durham Light Infantry carried the hill at the point of the bayonet, losing seven officers and sixty or seventy men, and capturing five Boer prisoners, besides ten horses and some wounded, Most of the enemy, however, had retired before the attack, unable to endure the appalling concentration of artillery which had prepared it. Among those who remained to fight to the last were five or six armed Kaffirs, one of whom shot an officer of the Durhams. To these no quarter was given. Their employment by the Dutch in this war shows that while they furiously complain of Khama's defence of his territory against their raiding parties on the ground that white men must be killed by white men, they have themselves no such scruples. There is no possible doubt about the facts set forth above, and the incident should be carefully noted by the public.

By nightfall the whole of General Lyttelton's Brigade had occupied Vaal Krantz, and were entrenching themselves. The losses in the day's fighting were not severe, and though no detailed statement has yet been compiled, I do not think they exceeded one hundred and fifty. Part of Sir Redvers Buller's plan had been successfully executed. The fact that the action had not been opened until 7 A.M. and had been conducted in a most leisurely manner left the programme only half completed. It remained to pass Clery's Division across the third bridge, to plant the batteries in their new position on Vaal Krantz, to set free the 1st Cavalry Brigade in the plain beyond, and to begin the main attack on Brakfontein. It remained and it still remains.

During the night of the 5th Lyttelton's Brigade made shelters and traverses of stones, and secured the possession of the hill; but it was now reported that field guns could not occupy the ridge because, first, it was too steep and rocky—though this condition does not apparently prevent the Boers dragging their heaviest guns to the tops of the highest hills—and, secondly, because the enemy's long-range rifle fire was too heavy. The hill, therefore, which had been successfully captured, proved of no value whatever. Beyond it was a second position which was of great strength, and which if it was ever to be taken must be taken by the Infantry without Artillery support. This was considered impossible or at any rate too costly and too dangerous to attempt.

During the next day the Boers continued to bombard the captured ridge, and also maintained a harassing long-range musketry fire. A great gun firing a hundred-pound 6-in. shell came into action from the top of Doornkloof, throwing its huge projectiles on Vaal Krantz and about the bivouacs generally; one of them exploded within a few yards of Sir Redvers Buller. Two Vickers-Maxims from either side of the Boer position fired at brief intervals, and other guns burst shrapnel effectively from very long range on the solitary brigade which held Vaal Krantz. To this bombardment the Field Artillery and the naval guns—seventy-two pieces in all, both big and little—made a noisy but futile response. The infantry of Lyttelton's Brigade, however, endured patiently throughout the day, in spite of the galling cross-fire and severe losses. At about four in the afternoon the Boers made a sudden attack on the hill, creeping to within short range, and then opened a quick fire. The Vickers-Maxim guns supported this vigorously. The pickets at the western end of the hill were driven back with loss, and for a few minutes it appeared that the hill would be retaken. But General Lyttelton ordered half a battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, supported by the King's Royal Rifles, to clear the hill, and these fine troops, led by Colonel Fitzgerald, rose up from their shelters and, giving three rousing cheers—the thin, distant sound of which came back to the anxious, watching army—swept the Boers back at the point of the bayonet. Colonel Fitzgerald was, however, severely wounded.

While these things were passing a new pontoon bridge was being constructed at a bend of the Tugela immediately under the Vaal Krantz ridge, and by five o'clock this was finished. Nothing else was done during the day, but at nightfall Lyttelton's Brigade was relieved by Hildyard's, which marched across the new pontoon (No. 4) under a desultory shell fire from an extreme range. Lyttelton's Brigade returned under cover of darkness to a bivouac underneath the Zwartkop guns. Their losses in the two days' operations had been 225 officers and men.

General Hildyard, with whom was Prince Christian Victor, spent the night in improving the defences of the hill and in building new traverses and head cover. At midnight the Boers made a fresh effort to regain the position, and the sudden roar of musketry awakened the sleeping army. The attack, however, was easily repulsed. At daybreak the shelling began again, only now the Boers had brought up several new guns, and the bombardment was much heavier. Owing, however, to the excellent cover which had been arranged the casualties during the day did not exceed forty. The Cavalry and Transport, who were sheltering in the hollows underneath Zwartkop, were also shelled, and it was thought desirable to move them back to a safer position.

In the evening Sir Redvers Buller, who throughout these two days had been sitting under a tree in a somewhat exposed position, and who had bivouacked with the troops, consulted with his generals. Many plans were suggested, but there was a general consensus of opinion that it was impossible to advance further along this line. At eleven at night Hildyard's Brigade was withdrawn from Vaal Krantz, evacuating the position in good order, and carrying with them their wounded, whom till dark it had been impossible to collect. Orders were issued for the general retirement of the army to Springfield and Spearman's, and by ten o'clock on the 8th this operation was in full progress.

With feelings of bitter disappointment at not having been permitted to fight the matter out, the Infantry, only two brigades of which had been sharply engaged, marched by various routes to their former camping grounds, and only their perfect discipline enabled them to control their grief and anger. The Cavalry and Artillery followed in due course, and thus the fourth attempt to relieve Ladysmith, which had been begun with such hopes and enthusiasm, fizzled out into failure. It must not, however, be imagined that the enemy conducted his defence without proportionate loss.

What I have written is a plain record of facts, and I am so deeply conscious of their significance that I shall attempt some explanation.

The Boer covering army numbers at least 12,000 men, with perhaps a dozen excellent guns. They hold along the line of the Tugela what is practically a continuous position of vast strength. Their superior mobility, and the fact that they occupy the chord, while we must move along the arc of the circle, enables them to forefront us with nearly their whole force wherever an attack is aimed, however it may be disguised. Therefore there is no way of avoiding a direct assault. Now, according to Continental experience the attacking force should outnumber the defence by three to one. Therefore Sir Redvers Buller should have 36,000 men. Instead of this he has only 22,000. Moreover, behind the first row of positions, which practically runs along the edge of an unbroken line of steep flat-topped hills, there is a second row standing back from the edge at no great distance. Any attack on this second row the Artillery cannot support, because from the plain below they are too far off to find the Boer guns, and from the edge they are too close to the enemy's riflemen. The ground is too broken, in the opinion of many generals, for night operations. Therefore the attacking Infantry of insufficient strength must face unaided the fire of cool, entrenched riflemen, armed with magazine weapons and using smokeless powder.

Nevertheless, so excellent is the quality of the Infantry that if the whole force were launched in attack it is not impossible that they would carry everything before them. But after this first victory it will be necessary to push on and attack the Boers investing Ladysmith. The line of communications must be kept open behind the relieving army or it will be itself in the most terrible danger. Already the Boers' position beyond Potgieter's laps around us on three sides. What if we should break through, only to have the door shut behind us? At least two brigades would have to be left to hold the line of communications. The rest, weakened by several fierce and bloody engagements, would not be strong enough to effect the relief.

The idea of setting all on the turn of the battle is very grateful and pleasant to the mind of the army, which only asks for a decisive trial of strength, but Sir Redvers Buller has to remember that his army, besides being the Ladysmith Relief Column, is also the only force which can be spared to protect South Natal. Is he, therefore, justified in running the greatest risks? On the other hand, how can we let Ladysmith and all its gallant defenders fall into the hands of the enemy? It is agonising to contemplate such a conclusion to all the efforts and sacrifices that have been made. I believe and trust we shall try again. As long as there is fighting one does not reflect on this horrible situation. I have tried to explain some of the difficulties which confront the General. I am not now concerned with the attempts that have been made to overcome them. A great deal is incomprehensible, but it may be safely said that if Sir Redvers Buller cannot relieve Ladysmith with his present force we do not know of any other officer in the British Service who would be likely to succeed.

CHAPTER XXI

HUSSAR HILL

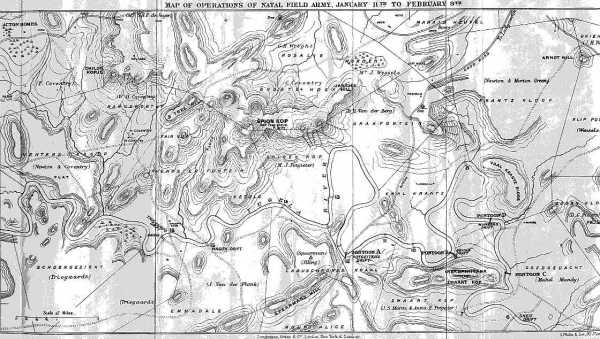

Map of the Operations of the Natal Field Army from January 11 to February 9

General Buller's Headquarters: February 15, 1900.

When Sir Redvers Buller broke off the combat of Vaal Krantz, and for the third time ordered his unbeaten troops to retreat, it was clearly understood that another attempt to penetrate the Boer lines was to be made without delay.

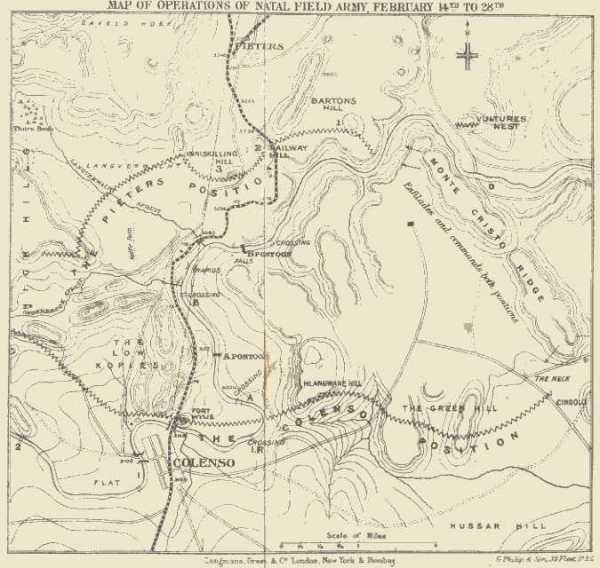

The army has moved from Spearman's and Springfield to Chieveley, General Lyttelton, who had succeeded Sir Francis Clery, in command of the 2nd Division and 4th Brigade, marching via Pretorius's Farm on the 9th and 10th, Sir Charles Warren covering the withdrawal of the supplies and transport and following on the 10th and 11th. The regular Cavalry Brigade, under Burn-Murdoch, was left with two battalions to hold the bridge at Springfield, beyond which place the Boers, who had crossed the Tugela in some strength at Potgieter's, were reported to be showing considerable activity. The left flank of the marching Infantry columns was covered by Dundonald's Brigade of Light Horse, and the operations were performed without interruption from the enemy. On the 12th orders were issued to reconnoitre Hussar Hill, a grassy and wooded eminence four miles to the east of Chieveley, and the direction of the next attack was revealed. The reader of the accounts of this war is probably familiar with the Colenso position and understands its great strength. The proper left of this position rests on the rocky, scrub-covered hill of Hlangwani, which rises on the British side of the Tugela. If this hill can be captured and artillery placed on it, and if it can be secured from cross fire, then all the trenches of Fort Wylie and along the river bank will be completely enfiladed, and the Colenso position will become untenable, so that Hlangwani is the key of the Colenso position. In order, however, to guard this key carefully the Boers have extended their left—as at Trichardt's Drift they extended their right—until it occupies a very lofty range of mountains four or five miles to the east of Hlangwani, and along all this front works have been constructed on a judicious system of defence. The long delays have given ample time to the enemy to complete his fortifications, and the trenches here are more like forts than field works, being provided with overhead cover against shells and carefully made loopholes. In front of them stretches a bare slope, on either side rise formidable hills from which long-range guns can make a continual cross-fire. Behind this position, again, are others of great strength.

But there are also encouraging considerations. We are to make—at least in spite of disappointments we hope and believe we are to make—a supreme effort to relieve Ladysmith. At the same time we are the army for the defence of South Natal. If we had put the matter to the test at Potgieter's and failed, our line of communications might have been cut behind us, and the whole army, weakened by the inevitable heavy losses of attacking these great positions, might have been captured or dispersed. Here we have the railway behind us. We are not as we were at Potgieter's 'formed to a flank.' We derive an accession of strength from the fact that the troops holding Railhead are now available for the general action.

Besides these inducements this road is the shortest way. Buller, therefore, has elected to lose his men and risk defeat—without which risk no victory can be won—-on this line. Whether he will succeed or not were foolish to prophesy, but it is the common belief that this line offers as good a chance as any other and that at last the army will be given a fair run, and permitted to begin a general engagement and fight it out to the end. If Buller goes in and wins he will have accomplished a wonderful feat of arms, and will gain the lasting honour and gratitude of his country. If he is beaten he will deserve the respect and sympathy of all true soldiers as a man who has tried to the best of his ability to perform a task for which his resources were inadequate. I hasten to return to the chronicle. Hussar Hill—so-called because a small post of the 13th Hussars was surprised on it six weeks ago and lost two men killed—is the high ground opposite Hlangwani and the mountainous ridges called Monte Cristo and Cingolo, on which the Artillery must be posted to prepare the attack. Hence the reconnaissance of the 12th.

At eight o'clock—we never get up early in this war—Lord Dundonald started from the cavalry camp near Stuart's Farm with the South African Light Horse, the Composite Regiment, Thorneycroft's Mounted Infantry, the Colt Battery, one battalion of Infantry, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and a battery of Field Artillery. The Irregular Horse were familiar with the ground, and we soon occupied Hussar Hill, driving back a small Boer patrol which was watching it, and wounding two of the enemy. A strong picket line was thrown out all round the captured ground and a dropping musketry fire began at long range with the Boers, who lay hidden in the surrounding dongas. At noon Sir Redvers Buller arrived, and made a prolonged reconnaissance of the ground with his telescope. At one o'clock we were ordered to withdraw, and the difficult task of extricating the advanced pickets from close contact with the enemy was performed under a sharp fire, fortunately without the loss of a man.

After you leave Hussar Hill on the way back to Chieveley camp it is necessary to cross a wide dip of ground. We had withdrawn several miles in careful rearguard fashion, the guns and the battalion had gone back, and the last two squadrons were walking across this dip towards the ridge on the homeward side. Perhaps we had not curled in our tail quite quick enough, or perhaps the enemy has grown more enterprising of late, in any case just as we were reaching the ridge a single shot was fired from Hussar Hill, and then without more ado a loud crackle of musketry burst forth. The distance was nearly two thousand yards, but the squadrons in close formation were a good target. Everybody walked for about twenty yards, and then without the necessity of an order broke into a brisk canter, opening the ranks to a dispersed formation at the same time. It was very dry weather, and the bullets striking between the horsemen raised large spurts of dust, so that it seemed that many men must surely be hit. Moreover, the fire had swelled to a menacing roar. I chanced to be riding with Colonel Byng in rear, and looking round saw that we had good luck. For though bullets fell among the troopers quite thickly enough, the ground two hundred yards further back was all alive with jumping dust. The Boers were shooting short.

We reached the ridge and cover in a minute, and it was very pretty to see these irregular soldiers stop their horses and dismount with their carbines at once without any hesitation. Along the ridge Captain Hill's Colt Battery was drawn up in line, and as soon as the front was clear the four little pink guns began spluttering furiously. The whole of the South African Light Horse dismounted and, lining the ridge, opened fire with their rifles. Thorneycroft's Mounted Infantry came into line on our left flank, and brought two tripod Maxims into action with them. Lord Dundonald sent back word to the battery to halt and fire over our heads, and Major Gough's Regiment and the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, who had almost reached cover, turned round of their own accord and hurried eagerly in the direction of the firing, which had become very loud on both sides.

There now ensued a strange little skirmish, which would have been a bloody rifle duel but for the great distance which separated the combatants and for the cleverness with which friends and foes concealed and sheltered themselves. Not less than four hundred men on either side were firing as fast as modern rifles will allow. Between us stretched the smooth green dip of ground. Beyond there rose the sharper outlines of Hussar Hill, two or three sheds, and a few trees. That was where the Boers were. But they were quite invisible to the naked eye, and no smoke betrayed their positions. With a telescope they could be seen—a long row of heads above the grass. We were equally hidden. Still their bullets—a proportion of their bullets—found us, and I earnestly trust that some of ours found them. Indeed there was a very hot fire, in spite of the range. Yet no one was hit. Ah, yes, there was one, a tall trooper turned sharply on his side, and two of his comrades carried him quickly back behind a little house, shot through the thigh. A little further along the firing line another was being helped to the rear. The Colt Battery drew the cream of the fire, and Mr. Garrett, one of the experts sent out by the firm, was shot through the ankle, but he continued to work his gun. Captain Hill walked up and down his battery exposing himself with great delight, and showing that he was a very worthy representative of an Irish constituency.

I happened to pass along the line on some duty or other when I noticed my younger brother, whose keen desire to take some part in the public quarrel had led me, in spite of misgivings, to procure him a lieutenancy, lying on the ground, with his troop. As I approached I saw him start in the quick, peculiar manner of a stricken man. I asked him at once whether he was hurt, and he said something—he thought it must be a bullet—had hit him on the gaiter and numbed his leg. He was quite sure it had not gone in, but when we had carried him away we found—as I expected—that he was shot through the leg. The wound was not serious, but the doctors declared he would be a month in hospital. It was his baptism of fire, and I have since wondered at the strange caprice which strikes down one man in his first skirmish and protects another time after time. But I suppose all pitchers will get broken in the end. Outwardly I sympathised with my brother in his misfortune, which he mourned bitterly, since it prevented him taking part in the impending battle, but secretly I confess myself well content that this young gentleman should be honourably out of harm's way for a month.

It was neither our business nor our pleasure to remain and continue this long-range duel with the Boers. Our work for the day was over, and all were anxious to get home to luncheon. Accordingly, as soon as the battery had come into action to cover our withdrawal we commenced withdrawing squadron by squadron and finally broke off the engagement, for the Boers were not inclined to follow further. At about three o'clock our loss in this interesting affair was one officer, Lieutenant John Churchill, and seven men of the South African Light Horse wounded and a few horses. Thorneycroft's Mounted Infantry also had two casualties, and there were two more in the Colt detachments. The Boers were throughout invisible, but two days later when the ground was revisited we found one dead burgher—so that at any rate they lost more heavily than we. The Colt guns worked very well, and the effect of the fire of a whole battery of these weapons was a marked diminution in the enemy's musketry. They were mounted on the light carriages patented by Lord Dundonald, and the advantage of these in enabling the guns to be run back by hand, so as to avoid exposing the horses, was very obvious.

I shall leave the great operation which, as I write, has already begun, to another letter, but since gaiety has its value in these troublous times let the reader pay attention to the story of General Hart and the third-class shot. Major-General Hart, who commands the Irish Brigade, is a man of intrepid personal courage—indeed, to his complete contempt for danger the heavy losses among his battalions, and particularly in the Dublin Fusiliers, must be to some extent attributed. After Colenso there were bitter things said on this account. But the reckless courage of the General was so remarkable in subsequent actions that, being brave men themselves, they forgave him everything for the sake of his daring. During the first day at Spion Kop General Hart discovered a soldier sitting safely behind a rock and a long way behind the firing line.

'Good afternoon, my man,' he said in his most nervous, apologetic voice; 'what are you doing here?'

'Sir,' replied the soldier, 'an officer told me to stop here, sir.'

'Oh! Why?'

'I'm a third-class shot, sir.'

'Dear me,' said the General after some reflection, 'that's an awful pity, because you see you'll have to get quite close to the Boers to do any good. Come along with me and I'll find you a nice place,' and a mournful procession trailed off towards the most advanced skirmishers.[3]

FOOTNOTES:

[3]The map at the end of Chapter XXV. illustrates this and succeeding chapters.

CHAPTER XXII

THE ENGAGEMENT OF MONTE CRISTO

Cingolo Neck: February 19, 1900.

Not since I wrote the tale of my escape from Pretoria have I taken up my pen with such feelings of satisfaction and contentment as I do to-night. The period of doubt and hesitation is over. We have grasped the nettle firmly, and as shrewdly as firmly, and have taken no hurt. It remains only to pluck it. For heaven's sake no over-confidence or premature elation; but there is really good hope that Sir Redvers Buller has solved the Riddle of the Tugela—at last. At last! I expect there will be some who will inquire—'Why not "at first"?' All I can answer is this: There is certainly no more capable soldier of high rank in all the army in Natal than Sir Redvers Buller. For three months he has been trying his best to pierce the Boer lines and the barrier of mountain and river which separates Ladysmith from food and friends; trying with an army—magnificent in everything but numbers, and not inconsiderable even in that respect—trying at a heavy price of blood in Africa, of anxiety at home. Now, for the first time, it seems that he may succeed. Knowing the General and the difficulties, I am inclined to ask, not whether he might have succeeded sooner, but rather whether anyone else would have succeeded at all. But to the chronicle!

Anyone who stands on Gun Hill near Chieveley can see the whole of the Boer position about Colenso sweeping before him in a wide curve. The mountain wall looks perfectly unbroken. The river lies everywhere buried in its gorge, and is quite invisible. To the observer there is only a smooth green bay of land sloping gently downward, and embraced by the rocky, scrub-covered hills. Along this crescent of high ground runs—or rather, by God's grace, ran the Boer line, strong in its natural features, and entrenched from end to end. When the map is consulted, however, it is seen that the Tugela does not flow uniformly along the foot of the hills as might be expected, but that after passing Colenso village, which is about the centre of the position, it plunges into the mountainous country, and bends sharply northward; so that, though the left of the Boer line might appear as strong as the right, there was this difference, that the Boer right had the river on its front, the Boer left had it in its rear.

The attack of the 15th of December had been directed against the Boer right, because after reconnaissance Sir Redvers Buller deemed that, in spite of the river advantage, the right was actually the weaker of the two flanks. The attack of the 15th was repulsed with heavy loss. It might, therefore, seem that little promise of success attended an attack on the Boer left. The situation, however, was entirely altered by the great reinforcements in heavy artillery which had reached the army, and a position which formerly appeared unassailable now looked less formidable.

Let us now consider the Boer left by itself. It ran in a chain of sangars, trenches, and rifle pits, from Colenso village, through the scrub by the river, over the rugged hill of Hlangwani, along a smooth grass ridge we called 'The Green Hill,' and was extended to guard against a turning movement on to the lofty wooded ridges of Monte Cristo and Cingolo and the neck joining these two features. Sir Redvers Buller's determination was to turn this widely extended position on its extreme left, and to endeavour to crumple it from left to right. As it were, a gigantic right arm was to reach out to the eastward, its shoulder at Gun Hill, its elbow on Hussar Hill, its hand on Cingolo, its fingers, the Irregular Cavalry Brigade, actually behind Cingolo.

On February 12th a reconnaissance in force of Hussar Hill was made by Lord Dundonald. On the 14th the army moved east from Chieveley to occupy this ground. General Hart with one brigade held Gun Hill and Railhead. The First Cavalry Brigade watched the left flank at Springfield, but with these exceptions the whole force marched for Hussar Hill. The Irregular Cavalry covered the front, and the South African Light Horse, thrown out far in advance, secured the position by half-past eight, just in time to forestall a force of Boers which had been despatched, so soon as the general movement of the British was evident, to resist the capture of the hill. A short sharp skirmish followed, in which we lost a few horses and men, and claim to have killed six Boers, and which was terminated after half an hour by the arrival of the leading Infantry battalion—the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. During the day the occupation was completed, and the brigades of Generals Wynne, Coke, and Barton, then joining Warren's Division with the Artillery, entrenched themselves strongly and bivouacked on the hill. Meanwhile Lyttelton's Division marched from its camp in the Blue Krantz Valley, east of Chieveley, along the valley to a position short of the eastern spurs of Hussar Hill. These spurs are more thickly wooded and broken than the rest of the hill, and about four o'clock in the afternoon some hundred Boers established themselves among the rocks and opened a sharp fire. They were, however, expelled from their position by the Artillery and by the fire of the advanced battalions of Lyttelton's Division operating from the Blue Krantz Valley.

During the 15th and 16th a desultory artillery duel proceeded on both sides with slight loss to us. The water question presented some difficulty, as the Blue Krantz River was several miles from Hussar Hill and the hill itself was waterless. A system of iron tanks mounted on ox waggons was arranged, and a sufficient though small supply maintained. The heavy artillery was also brought into action and strongly entrenched. The formidable nature of the enemy's position and the evident care with which he had fortified it may well have added to the delay by giving cause for the gravest reflection.

On the afternoon of the 16th Sir Redvers Buller resolved to plunge, and orders were issued for a general advance at dawn. Colonel Sandbach, under whose supervision the Intelligence Department has attained a new and a refreshing standard of efficiency, made comprehensive and, as was afterwards proved, accurate reports of the enemy's strength and spirit, and strongly recommended the attack on the left flank. Two hours before dawn the army was on the move. Hart's Brigade, the 6-inch and other great guns at Chieveley, guarded Railhead. Hlangwani Hill, and the long line of entrenchments rimming the Green Hill, were masked and fronted by the display of the field and siege batteries, whose strength in guns was as follows:

Guns

Four 5-inch siege guns.......................... 4

Six naval twelve-pounder long-range guns........ 6

Two 4.7-inch naval guns.............................. 2

One battery howitzers........................... 6

One battery corps artillery (R.F.A.)............ 6

Two brigade divisions R.F.A ....................36

One mountain battery............................ 6

—

66and which were also able to prepare and support the attack on Cingolo Neck and Monte Cristo Ridge. Cingolo Ridge itself, however, was almost beyond their reach. Lyttelton's Division with Wynne's Fusilier Brigade was to stretch out to the eastward and, by a wide turning movement pivoting on the guns and Barton's Brigade, attack the Cingolo Ridge. Dundonald's Cavalry Brigade was to make a far wider detour and climb up the end of the ridge, thus making absolutely certain of finding the enemy's left flank at last.

By daybreak all were moving, and as the Irregular Cavalry forded the Blue Krantz stream on their enveloping march we heard the boom of the first gun. The usual leisurely bombardment had begun, and I counted only thirty shells in the first ten minutes, which was not very hard work for the gunners considering that nearly seventy guns were in action. But the Artillery never hurry themselves, and indeed I do not remember to have heard in this war a really good cannonade, such as we had at Omdurman, except for a few minutes at Vaal Krantz.

The Cavalry Brigade marched ten miles eastward through most broken and difficult country, all rock, high grass, and dense thickets, which made it imperative to move in single file, and the sound of the general action grew fainter and fainter. Gradually, however, we began to turn again towards it. The slope of the ground rose against us. The scrub became more dense. To ride further was impossible. We dismounted and led our horses, who scrambled and blundered painfully among the trees and boulders. So scattered was our formation that I did not care to imagine what would have happened had the enemy put in an appearance. But our safety lay in these same natural difficulties. The Boers doubtless reflected, 'No one will ever try to go through such ground as that'—besides which war cannot be made without running risks. The soldier must chance his life.

The general must not be afraid to brave disaster. But how tolerant the arm-chair critics should be of men who try daring coups and fail! You must put your head into the lion's mouth if the performance is to be a success. And then I remembered the attacks on the brave and capable General Gatacre after Stormberg, and wondered what would be said of us if we were caught 'dismounted and scattered in a wood.'

At length we reached the foot of the hill and halted to reconnoitre the slopes as far as was possible. After half an hour, since nothing could be seen, the advance was resumed up the side of a precipice and through a jungle so thick that we had to cut our road. It was eleven o'clock before we reached the summit of the ridge and emerged on to a more or less open plateau, diversified with patches of wood and heaps of great boulders. Two squadrons had re-formed on the top and had deployed to cover the others. The troopers of the remaining seven squadrons were working their way up about four to the minute. It would take at least two hours before the command was complete: and meanwhile! Suddenly there was a rifle shot. Then another, then a regular splutter of musketry. Bullets began to whizz overhead. The Boers had discovered us.

Now came the crisis. There might be a hundred Boers on the hill, in which case all was well. On the other hand there might be a thousand, in which case——! and retreat down the precipice was, of course, quite out of the question. Luckily there were only about a hundred, and after a skirmish, in which one of the Natal Carabineers was unhappily killed, they fell back and we completed our deployment on the top of the hill.

The squadron of Imperial Light Horse and the Natal Carabineers now advanced slowly along the ridge, clearing it of the enemy, slaying and retrieving one field cornet and two burghers, and capturing ten horses. Half-way along the Queen's, the right battalion of Hildyard's attack, which, having made a smaller detour, had now rushed the top, came into line and supported the dismounted men. The rest of the Cavalry descended into the plain on the other side of the ridge, outflanking and even threatening the retreat of its defenders, so that in the end the Boers, who were very weak in numbers, were hunted off the ridge altogether, and Cingolo was ours. Cingolo and Monte Cristo are joined together by a neck of ground from which both heights rise steeply. On either side of Monte Cristo and Cingolo long spurs run at right angles to the main hill.

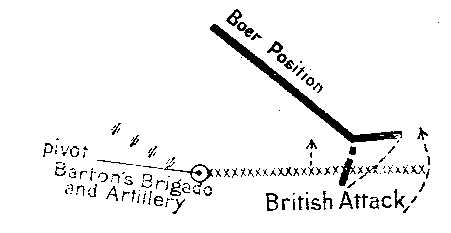

By the operations of the 17th the Boer line had been twisted off Cingolo, and turned back along the subsidiary spurs of Monte Cristo, and the British forces had placed themselves diagonally across the left of the Boer position thus:

Plan of position at Monte Cristo

The advantages of this situation were to be enjoyed on the morrow.

Finding our further advance barred by the turned-back position the enemy had adopted, and which we could only attack frontally, the Cavalry threw out a line of outposts which were soon engaged in a long-range rifle duel, and prepared to bivouac for the night. Cingolo Ridge was meanwhile strongly occupied by the Infantry, whose line ran from its highest peak slantwise across the valley of the Gomba Stream to Hussar Hill, where it found its pivot in Barton's Brigade and the Artillery. The Boers, who were much disconcerted by the change in the situation, showed themselves ostentatiously on the turned-back ridge of their position as if to make themselves appear in great strength, and derisively hoisted white flags on their guns. The Colonial and American troopers (for in the South African Light Horse we have a great many Americans, and one even who served under Sheridan) made some exceedingly good practice at the extreme ranges. So the afternoon passed, and the night came in comparative quiet.

At dawn the artillery began on both sides, and we were ourselves awakened by Creusot shells bursting in our bivouac. The enemy's fire was chiefly directed on the company of the Queen's which was holding the top of Cingolo, and only the good cover which the great rocks afforded prevented serious losses. As it was several men were injured. But we knew that we held the best cards; and so did the Boers. At eight o'clock Hildyard's Brigade advanced against the peak of the Monte Cristo ridge which lay beyond the neck. The West Yorks led, the Queen's and East Surrey supported. The musketry swelled into a constant crackle like the noise of a good fire roaring up the chimney, but, in spite of more than a hundred casualties, the advance never checked for an instant, and by half-past ten o'clock the bayonets of the attacking infantry began to glitter among the trees of the summit. The Boers, who were lining a hastily-dug trench half way along the ridge, threatened in front with an overwhelming force and assailed in flank by the long-range fire of the Cavalry, began to fall back. By eleven o'clock the fight on the part of the enemy resolved itself into a rearguard action.

Under the pressure of the advancing and enveloping army this degenerated very rapidly. When the Dutchman makes up his mind to go he throws all dignity to the winds, and I have never seen an enemy leave the field in such a hurry as did these valiant Boers who found their flank turned, and remembered for the first time that there was a deep river behind them. Shortly after twelve o'clock the summit of the ridge of Monte Cristo was in our hands. The spurs which started at right angles from it were, of course, now enfiladed and commanded. The Boers evacuated both in great haste. The eastern spur was what I have called the 'turned-back' position. The Cavalry under Dundonald. galloped forward and seized it as soon as the enemy were seen in motion, and from this advantageous standpoint we fired heavily into their line of retreat. They scarcely waited to fire back, and we had only two men and a few horses wounded.

The spur on the Colenso or western side was none other than the Green Hill itself, and judging rightly that its frowning entrenchments were now empty of defenders Sir Redvers Buller ordered a general advance frontally against it. Two miles of trenches were taken with scarcely any loss. The enemy fled in disorder across the river. A few prisoners, some wounded, several cartloads of ammunition and stores, five camps with all kinds of Boer material, and last of all, and compared to which all else was insignificant, the dominating Monte Cristo ridge stretching northward to within an easy spring of Bulwana Hill, were the prize of victory. The soldiers, delighted at the change of fortune, slept in the Boer tents—or would have done had these not been disgustingly foul and stinking.

From the captured ridge we could look right down into Ladysmith, and at the first opportunity I climbed up to see it for myself. Only eight miles away stood the poor little persecuted town, with whose fate there is wrapt up the honour of the Empire, and for whose sake so many hundred good soldiers have given life or limb—a twenty-acre patch of tin houses and blue gum trees, but famous to the uttermost ends of the earth.

The victory of Monte Cristo has revolutionised the situation in Natal. It has laid open a practicable road to Ladysmith. Great difficulties and heavy opposition have yet to be encountered and overcome, but the word 'impossible' must no longer be—should, perhaps, never have been used. The success was won at the cost of less than two hundred men killed and wounded, and surely no army more than the Army of Natal deserves a cheaply bought triumph.

CHAPTER XXIII

THE PASSAGE OF THE TUGELA

Hospital Ship 'Maine': March 4, 1900.

Since I finished my last letter, on February the 21st, I have found no time to sit down to write until now, because we have passed through a period of ceaseless struggle and emotion, and I have been seeing so many things that I could not pause to record anything. It has been as if a painter prepared himself to paint some portrait, but was so fascinated by the beauty of his model that he could not turn his eyes from her face to the canvas; only that the spectacles which have held me have not always been beautiful. Now the great event is over, the long and bloody conflict around Ladysmith has been gloriously decided, and I take a few days' leisure on the good ship Maine, where everyone is busy getting well, to think about it all and set down some things on paper.

First and foremost there was the Monte Cristo ridge, that we had captured on the 18th, which gave us the Green Hill, Hlangwani Hill, and, when we chose to take it, the whole of the Hlangwani plateau. The Monte Cristo ridge is the centrepiece to the whole of this battle. As soon as we had won it I telegraphed to the Morning Post that now at last success was a distinct possibility. With this important feature in our possession it was certain that we held the key to Ladysmith, and though we might fumble a little with the lock, sooner or later, barring the accidents of war, we should open the door.

As Monte Cristo had given Sir Redvers Buller Hlangwani, so Hlangwani rendered the whole of the western section (the eastern section was already in our hands) of the Colenso position untenable by the enemy, and they, finding themselves commanded and enfiladed, forthwith evacuated it. On the 19th General Buller made good his position on Green Hill, occupied Hlangwani with Barton's Brigade, built or improved his roads and communications from Hussar Hill across the Gomba Valley, and brought up his heavy guns. The Boers, who were mostly on the other side of the river, resisted stubbornly with artillery, with their Vickers-Maxim guns and the fire of skirmishers, so that we suffered some slight loss, but could not be said to have wasted the day. On the 20th the south side of the Tugela was entirely cleared of the enemy, who retired across the bridge they had built, and, moreover, a heavy battery was established on the spurs of Hlangwani to drive them out of Colenso. In the afternoon Hart's Brigade advanced from Chieveley, and his leading-battalion, under Major Stuart-Wortley, occupied Colenso village without any resistance.

The question now arose—Where should the river be crossed? Sir Redvers Buller possessed the whole of the Hlangwani plateau, which, as the reader may perceive by looking at the map opposite p. 448, fills up the re-entrant angle made opposite Pieters by the Tugela after it leaves Colenso. From this Hlangwani plateau he could either cross the river where it ran north and south or where it ran east and west. Sir Redvers Buller determined to cross the former reach beyond Colenso village. To do this he had to let go his hold on the Monte Cristo ridge and resign all the advantages which its possession had given him, and had besides to descend into the low ground, where his army must be cramped between the high hills on its left and the river on its right.

There was, of course, something to be said for the other plan, which was advocated strongly by Sir Charles Warren. The crossing, it was urged, was absolutely safe, being commanded on all sides by our guns, and the enemy could make no opposition except with artillery. Moreover, the army would get on its line of railway and could 'advance along the railroad.' This last was a purely imaginary advantage, to be sure, because the railway had no rolling-stock, and was disconnected from the rest of the line by the destruction of the Tugela bridge. But what weighed with the Commander-in-Chief much more than the representations of his lieutenant was the accumulating evidence that the enemy were in full retreat. The Intelligence reports all pointed to this situation. Boers had ridden off in all directions. Waggons were seen trekking along every road to the north and west. The camps between us and Ladysmith began to break up. Everyone said, 'This is the result of Lord Roberts's advance: the Boers find themselves now too weak to hold us off. They have raised the siege.'

But this conclusion proved false in the sense that it was premature. Undoubtedly the Boers had been reduced in strength by about 5,000 men, who had been sent into the Free State for its defence. Until the Monte Cristo ridge was lost to them they deemed themselves quite strong enough to maintain the siege. When, however, this position was captured, the situation was revolutionised. They saw that we had found their flank, and thoroughly appreciated the significance and value of the long high wedge of ground, which cut right across the left of their positions, and seemed to stretch away almost to Bulwana Mountain. They knew perfectly well that if we advanced by our right along the line of this ridge, which they called 'the Bush Kop,' supporting ourselves by it as a man might rest his hand on a balustrade, we could turn their Pieters position just as we had already turned their entrenchments at Colenso.

Therein lay the true reason of their retirement, and in attributing it either to Lord Roberts's operations or to the beating we had given them on the 18th we made a mistake, which was not repaired until much blood had been shed.

I draw a rough diagram to assist the reader who will take the trouble to study the map. It is only drawn from memory, and its object is to show how completely the Monte Cristo ridge turned both the line of entrenchments through Colenso and that before Pieters. But no diagrams, however exaggerated, would convince so well as would the actual ground.

Plan of the Colenso Position

Plan of the Colenso PositionIn the belief, however, that the enemy were in retreat the General resolved to cross the river at A by a pontoon bridge and follow the railway line. On the 21st, therefore, he moved his army westward across the Hlangwani plateau, threw his bridge, and during the afternoon passed his two leading infantry brigades over it. As soon as the Boers perceived that he had chosen this line of advance their hopes revived. 'Oh,' we may imagine them saying, 'if you propose to go that way, things are not so bad after all.' So they returned to the number of about nine thousand burghers, and manned the trenches of the Pieters position, with the result that Wynne's Lancashire Brigade, which was the first to cross, soon found itself engaged in a sharp action among the low-kopjes, and suffered a hundred and fifty casualties, including its General, before dark. Musketry fire was continuous throughout the night. The 1st Cavalry Brigade had been brought in from Springfield on the 20th, and on the morning of the 22nd both the Regular and Irregular Cavalry were to have crossed the river. We accordingly marched from our camp at the neck between Cingolo and Monte Cristo and met the 1st Cavalry Brigade, which had come from Chievejey, at the pontoon bridge. A brisk action was crackling away beyond the river, and it looked as if the ground scarcely admitted of our intervention. Indeed, we had hardly arrived when a Staff Officer came up, and brought us orders to camp near Hlangwani Hill, as we should not cross that day.

Presently I talked to the Staff Officer, who chanced to be a friend of mine, and chanced, besides, to be a man with a capacity for sustained thought, an eye for country, and some imagination. He said: 'I don't like the situation; there are more of them than we expected. We have come down off our high ground. We have taken all the big guns off the big hills. We are getting ourselves cramped up among these kopjes in the valley of the Tugela. It will be like being in the Coliseum and shot at by every row of seats.'

Sir Redvers Buller, however, still believing he had only a rearguard in front of him, was determined to persevere. It is, perhaps, his strongest characteristic obstinately to pursue his plan in spite of all advice, in spite, too, of his horror of bloodshed, until himself convinced that it is impracticable. The moment he is satisfied that this is the case no considerations of sentiment or effect prevent him from coming back and starting afresh. No modern General ever cared less for what the world might say. However unpalatable and humiliating a retreat might be, he would make one so soon as he was persuaded that adverse chances lay before him. 'To get there in the end,' was his guiding principle. Nor would the General consent to imperil the ultimate success by asking his soldiers to make a supreme effort to redress a false tactical move. It was a principle which led us to much blood and bitter disappointment, but in the end to victory.

Not yet convinced, General Buller, pressing forward, moved the whole of his infantry, with the exception of Barton's Brigade, and nearly all the artillery, heavy and field, across the river, and in the afternoon sent two battalions from Norcott's Brigade and the Lancashire Brigade—to the vacant command of which Colonel Kitchener had been appointed—forward against the low kopjes. By nightfall a good deal of this low, rolling ground was in our possession, though at some cost in men and officers.

At dusk the Boers made a fierce and furious counter-attack. I was watching the operations from Hlangwani Hill through a powerful telescope. As the light died my companions climbed down the rocks to the Cavalry camp and left me alone staring at the bright flashes of the guns which stabbed the obscurity on all sides. Suddenly, above the booming of the cannon, there arose the harsh rattling roar of a tremendous fusillade. Without a single intermission this continued for several hours. The Howitzer Battery, in spite of the darkness, evidently considered the situation demanded its efforts, and fired salvoes of lyddite shells, which, bursting in the direction of the Boer positions, lit up the whole scene with flaring explosions. I went anxiously to bed that night, wondering what was passing beyond the river, and the last thing I can remember was the musketry drumming away with unabated vigour.

There was still a steady splutter at dawn on the 23rd, and before the light was full grown the guns joined in the din. We eagerly sought for news of what had passed. Apparently the result was not unfavourable to the army. 'Push for Ladysmith to-day, horse, foot, and artillery' was the order, 'Both cavalry brigades to cross the river at once.' Details were scarce and doubtful. Indeed, I cannot yet give any accurate description of the fighting on the night of the 22nd, for it was of a confused and desperate nature, and many men must tell their tale before any general account can be written.

What happened, briefly described, was that the Boers attacked heavily at nightfall with rifle fire all along the line, and, in their eagerness to dislodge the troops, came to close quarters on several occasions at various points. At least two bayonet charges are recorded. Sixteen men of Stuart Wortley's Composite Battalion of Reservists of the Rifle Brigade and King's Royal Rifles showed blood on their bayonets in the morning. About three hundred officers and men were killed or wounded. The Boers also suffered heavily, leaving dead on the ground, among others a grandson of President Kruger. Prisoners were made and lost, taken and rescued by both sides; but the daylight showed that victory rested with the British, for the infantry were revealed still tenaciously holding all their positions.

At eight o'clock the cavalry crossed the river under shell fire directed on the bridge, and were massed at Fort Wylie, near Colenso. I rode along the railway line to watch the action from one of the low kopjes. A capricious shell fire annoyed the whole army as it sheltered behind the rocky hills, and an unceasing stream of stretchers from the front bore true witness to the serious nature of the conflict, for this was the third and bloodiest day of the seven days' fighting called the battle of Pieters.

I found Sir Redvers Buller and his Staff in a somewhat exposed position, whence an excellent view could be obtained. The General displayed his customary composure, asked me how my brother's wound was getting on, and told me that he had just ordered Hart's Brigade, supported by two battalions from Lyttelton's Division, to assault the hill marked '3' on my diagram, and hereinafter called Inniskilling Hill. 'I have told Hart to follow the railway. I think he can get round to their left flank under cover of the river bank,' he said, 'but we must be prepared for a counter-attack on our left as soon as they see what I'm up to;' and he then made certain dispositions of his cavalry, which brought the South African Light Horse close up to the wooded kopje on which we stood. I must now describe the main Pieters position, one hill of which was about to be attacked.

It ran, as the diagram shows, from the high and, so far as we were concerned, inaccessible hills on the west to the angle of the river, and then along the three hills marked 3, 2, and 1. I use this inverted sequence of numbers because we were now attacking them in the wrong order.

Sir Redvers Buller's plan was as follows: On the 22nd he had taken the low kopjes, and his powerful artillery gave him complete command of the river gorge. Behind the kopjes, which acted as a kind of shield, and along the river gorge he proposed to advance his infantry until the angle of the river was passed and there was room to stretch out his, till then, cramped right arm and reach round the enemy's left on Inniskilling Hill, and so crumple it.

This perilous and difficult task was entrusted to the Irish Brigade, which comprised the Dublin Fusiliers, the Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Connaught Rangers, and the Imperial Light Infantry, who had temporarily replaced the Border Regiment—in all about three thousand men, supported by two thousand more. Their commander, General Hart, was one of the bravest officers in the army, and it was generally felt that such a leader and such troops could carry the business through if success lay within the scope of human efforts.

The account of the ensuing operation is so tragic and full of mournful interest that I must leave it to another letter.

CHAPTER XXIV

THE BATTLE OF PIETERS: THE THIRD DAY

Hospital ship 'Maine': March 5, 1900.

At half-past twelve on the 23rd General Hart ordered his brigade to advance. The battalions, which were sheltering among stone walls and other hastily constructed cover on the reverse slope of the kopje immediately in front of that on which we stood, rose up one by one and formed in rank. They then moved off in single file along the railroad, the Inniskilling Fusiliers leading, the Connaught Rangers, Dublin Fusiliers, and the Imperial Light Infantry following in succession. At the same time the Durham Light Infantry and the 2nd Rifle Brigade began to march to take the place of the assaulting brigade on the advanced kopje. Wishing to have a nearer view of the attack, I descended the wooded hill, cantered along the railway—down which the procession of laden stretchers, now hardly interrupted for three days, was still moving—and, dismounting, climbed the rocky sides of the advanced kopje. On the top, in a little half-circle of stones, I found General Lyttelton, who received me kindly, and together we watched the development of the operation. Nearly a mile of the railway line was visible, and along it the stream of Infantry flowed steadily. The telescope showed the soldiers walking quite slowly, with their rifles at the slope. Thus far, at least, they were not under fire. The low kopjes which were held by the other brigades shielded the movement. A mile away the river and railway turned sharply to the right; the river plunged into a steep gorge, and the railway was lost in a cutting. There was certainly plenty of cover; but just before the cutting was reached the iron bridge across the Onderbrook Spruit had to be crossed, and this was evidently commanded by the enemy's riflemen. Beyond the railway and the moving trickle of men the brown dark face of Inniskilling Hill, crowned with sangars and entrenchments, rose up gloomy and, as yet, silent.

The patter of musketry along the left of the army, which reached back from the advanced kopjes to Colenso village, the boom of the heavy guns across the river, and the ceaseless thudding of the Field Artillery making a leisurely preparation, were an almost unnoticed accompaniment to the scene. Before us the Infantry were moving steadily nearer to the hill and the open ground by the railway bridge, and we listened amid the comparatively peaceful din for the impending fire storm.

The head of the column reached the exposed ground, and the soldiers began to walk across it. Then at once above the average fusillade and cannonade rose the extraordinary rattling roll of Mauser musketry in great volume. If the reader wishes to know exactly what this is like he must drum the fingers of both his hands on a wooden table, one after the other as quickly and as hard as he can. I turned my telescope on the Dutch defences. They were no longer deserted. All along the rim of the trenches, clear cut and jet black, against the sky stood a crowded line of slouch-hatted men, visible as far as their shoulders, and wielding what looked like thin sticks.

Far below by the red ironwork of the railway bridge—2,000 yards, at least, from the trenches—the surface of the ground was blurred and dusty. Across the bridge the Infantry were still moving, but no longer slowly—they were running for their lives. Man after man emerged from the sheltered railroad, which ran like a covered way across the enemy's front, into the open and the driving hail of bullets, ran the gauntlet and dropped down the embankment on the further side of the bridge into safety again. The range was great, but a good many soldiers were hit and lay scattered about the ironwork of the bridge. 'Pom-pom-pom,' 'pom-pom-pom,' and so on, twenty times went the Boer automatic gun, and the flights of little shells spotted the bridge with puffs of white smoke. But the advancing Infantry never hesitated for a moment, and continued to scamper across the dangerous ground, paying their toll accordingly. More than sixty men were shot in this short space. Yet this was not the attack. This was only the preliminary movement across the enemy's front.

The enemy's shells, which occasionally burst on the advanced kopje, and a whistle of stray bullets from the left, advised us to change our position, and we moved a little further down the slope towards the river. Here the bridge was no longer visible. I looked towards the hill-top, whence the roar of musketry was ceaselessly proceeding. The Artillery had seen the slouch hats, too, and forgetting their usual apathy in the joy of a live target, concentrated a most hellish and terrible fire on the trenches.

Meanwhile the afternoon had been passing. The Infantry had filed steadily across the front, and the two leading battalions had already accumulated on the eastern spurs of Inniskilling Hill. At four o'clock General Hart ordered the attack, and the troops forthwith began to climb the slopes. The broken ground delayed their progress, and it was nearly sunset by the time they had reached the furthest position which could be gained under cover. The Boer entrenchments were about four hundred yards away. The arête by which the Inniskillings had advanced was bare, and swept by a dreadful frontal fire from the works on the summit and a still more terrible flanking fire from the other hills. It was so narrow that, though only four companies were arranged in the firing line, there was scarcely room for two to deploy. There was not, however, the slightest hesitation, and as we watched with straining eyes we could see the leading companies rise up together and run swiftly forward on the enemy's works with inspiring dash and enthusiasm.

But if the attack was superb, the defence was magnificent; nor could the devoted heroism of the Irish soldiers surpass the stout endurance of the Dutch. The Artillery redoubled their efforts. The whole summit of the hill was alive with shell. Shrapnel flashed into being above the crests, and the ground sprang up into dust whipped by the showers of bullets and splinters. Again and again whole sections of the entrenchments vanished in an awful uprush of black earth and smoke, smothering the fierce blaze of the lyddite shells from the howitzers and heavy artillery. The cannonade grew to tremendous thundering hum. Not less than sixty guns were firing continuously on the Boer trenches. But the musketry was never subdued for an instant. Amid the smoke and the dust the slouch hats could still be seen. The Dutch, firm and undaunted, stood to their parapets and plied their rifles with deadly effect.

The terrible power of the Mauser rifle was displayed. As the charging companies met the storm of bullets they were swept away. Officers and men fell by scores on the narrow ridge. Though assailed in front and flank by the hideous whispering Death, the survivors hurried obstinately onward, until their own artillery were forced to cease firing, and it seemed that, in spite of bullets, flesh and blood would prevail. But at the last supreme moment the weakness of the attack was shown. The Inniskillings had almost reached their goal. They were too few to effect their purpose; and when the Boers saw that the attack had withered they shot all the straighter, and several of the boldest leapt out from their trenches and, running forward to meet the soldiers, discharged their magazines at the closest range. It was a frantic scene of blood and fury.