13. "THE GREAT WAR" (WORLD WAR ONE)

WAR CLOUDS GATHER

CONTENTS

The path to world war The path to world war

Tsar Nicholas II's Russia Tsar Nicholas II's Russia

Ottoman Turkey Ottoman Turkey

The Balkan Wars as prelude to the The Balkan Wars as prelude to the

coming "Great War"

Growing tensions among the majo Growing tensions among the majo

European powers

War fever refuses to cool down War fever refuses to cool down

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 67-78.

By

the opening days of the twentieth century the Europeans and Americans

had clearly put the political-cultural stamp of the Christian West on

most of the rest of the world. This would mark the peak of

Western glory. It would also mark the beginning of its

political-cultural decline ... at least with respect to Europe’s part

in the Western political-cultural dynamic.

Ironically it was the very sense of Western "progressivism" that would

be its undoing. The rising theory of the "sovereignty of the

people" – as opposed to the sovereignty of their traditional lords

(kings and emperors) – sounded so noble, so progressive. But it

contained a set of social dynamics that no one seemed able either to

understand or manage when set loose. Thus the first half of

the twentieth century would be marked by not only levels of violence

not seen in centuries, it would also bring the decline in global

influence of those very groups who thought themselves to be the

teachers of "good citizenship" and "proper civilization" to the rest of

the world.

In the earlier days of the recognized importance of kings and emperors

as the glue bonding numerous societies into a single whole, offering

stability and peace for the common people in the process, kingdoms and

empires made a great deal of political sense. They could unite

the most varied of people ... even ones who otherwise would be at each

other’s throats because of more local hatreds possessing deep

historical roots. Thus just as the Austro-Hungarian Empire held

together Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Bohemians (Czechs), Moravians,

Ruthenians, etc. with Lutheran, Calvinist, Catholic, Orthodox religious

self-identities as well ... the Ottoman Empire united Turks, Arabs,

Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, etc., also of a wide religious variety

as Sunni, Shi’ite, Druze and Alawi Muslims and Catholic, Orthodox and

Coptic Christians.

The problems of tribal "group-think" or "nationalism."

Now with the arrival of the "Age of Nationalism," each of these smaller

ethnic/religious sub-groups was expected to define, defend and promote

its own "national" identity … a task muddied greatly by the fact that

there were no clear geographic borders separating these sub-groups into

distinct national packages. While there were certainly points of

concentration on the map for one or another of these sub-groups, they

found themselves scattered amidst other sub-groups as you moved outward

from these central points. Just trying to draw national

boundaries among these subgroups was guaranteed to pit one group

violently against another (or even several others!)

Furthermore, a kind of nationalist "Romanticism" had turned the very

idea of the nation itself into a highly revered, even worshiped, object

of social affection ("group think") … something not really allowable

during the previous centuries of dynastic rule in the West. But

with the rise of the political urges of the masses – birthed by

Napoleon and his "nationalist" armies in the early 1800s – dynastic

governments now found themselves on a steady political retreat in

Europe. The dynasties that continued in place no longer

represented merely their own family interests … but were there to

cultivate this larger group-think, to bring the people they presided

over to ever-grander political purpose. But these dynasties –

untrained in the ways of popular democracy – possessed very little

understanding, and in some cases no understanding at all, of the forces

they were unleashing in their efforts to govern their increasingly

nationalistic societies. Thus it was that the forces of

nationalism constituted a powder keg waiting to explode.

Tragically the utopian idealists and nationalist dreamers were

completely self-blinded on this subject (as they still are

today). The theory of "the self-determination of peoples

everywhere" sounded so noble … especially to intellectuals far removed

from the practical difficulties found in the realm of political

actuality.

The basic requirements of social success.

Self-government of a people is a great idea … provided that the people

themselves have a well-practiced habit of moral self-discipline, a

habit built on the foundations of a well-supported system of laws and

social boundaries … ones that have proven themselves through the test

of time. Trendy, and thus untested, political ideas and ideals

must always be viewed with much caution.

The people must also possess a spirit of social compromise based on the

understanding that they must first look to the larger challenges facing

them collectively as a people … rather than get caught up with more

immediate local matters, ones that so much more easily draw their

attention and arouse their emotions.

And political wisdom demands that this sense of collective challenge

must not just stop at the national border … but extend to other people

groups, other societies, other tribes and nations besides their

own. Working with others not only amplifies the social power

available to a people to work with, it also tends to broaden a people's

sense of political self-interest to a much higher realm – the lofty but

complex realm of international politics

.

The massive tragedy that was about to hit Europe – and bring its days

as the world's power center into rapid decline – happened because this

same wisdom, this vital realism, was lacking in Europe's various

nations … and especially in their leadership.

Indeed, excellent leadership is critical to a society trying to live to

higher social standards. But finding such leadership is always a

serious challenge facing any society.

To be a great leader, a person must possess not only a great intellect but also a deep wisdom

… a wisdom achieved through excellent early education, through the

careful attention paid to earlier generations of a life of proven

success, and then through considerable personal experience in seeing

all those learned lessons of life put to the test.

But also to be a great leader, a person must possess a high degree of personal ambition,

one able to keep a person going in the not-uncommon face of grand

disappointments – even failures – in the early effort to find success …

and then in success, the ability not to give in to a reactive

opposition that success naturally provokes in the hearts of other

equally-ambitious competitors.

Thus importantly, it requires both wisdom and ambition to produce a

great leader. But on the one hand, there are always wise ones in

society who (maybe most wisely itself!) choose not to get involved in

the rough-and-tumble game of politics. And on the other hand,

there are always the very ambitious – but not so wise – ones … ones who

are so caught up in their own personal success that they possess none

of the greater wisdom that society will need in facing its

challenges. Tragically it is exactly this latter group that can

actually bring a society to defeat, even to collapse.

So … coming up with a great leader is not a matter easily secured for a society.

The challenges facing Western society at this point.

As it enters the twentieth century, the Western world will find itself

facing exactly this very challenge. Indeed, lacking tested

leadership in the newly rising world of "democracy," the move to

self-government will become a formula for a savage breakdown in the

European social order – in which thousands, hundreds of thousands, even

millions of ordinary people will get sacrificed to the gods of rising

nationalism.

But it was not just dreamy "Progressivists" who were guilty of shaping

this terrible social disaster. It was also kings and emperors

themselves who did not understand what was going on right under their

noses, and so managed to do the worst of things at the worst of

moments, activity well designed to make a complicated situation

virtually unmanageable, and ultimately catastrophic.

Some leaders seemed particularly expert in this regard. Chief

among them was Nicholas II of Russia (r. 1894-1917), who had virtually

no understanding of the mentality of the Russian peasants he was

reigning over.

There was also Franz Joseph, the Austro-Hungarian emperor, who though a

man of some intelligence, was nonetheless in over his head leading an

empire made up of a multitude of contending national groups, groups

that had few political interests in common. And sadly, Franz

Joseph’s Austria-Hungary was not content in possessing this

unmanageable bag of contending nationalities. Austria-Hungary

seemed determined to acquire even additional national groups, such as

the Serbs, just to the south of the Austrian-Hungarian border.

Serbs, of course, had other thoughts on this matter, especially the

hyper-nationalists among them.

In fact it would be this very problem brewing between the Austrians and

the Serbs that would finally set off the fires of war, which once

ignited, seemingly could not be put out. And so a pointless

bloodletting ensued, dragging itself out for four whole years.

Finally America brought new blood into the exhausted mix, breaking the

deadlock and tipping the balance of power in favor of one side over the

other, bringing the war finally to an equally pointless end.

Tragically the war would cripple the participants so badly that Europe,

even in the period of post-war "peace," would be unable to reclaim its

former position of world influence. The decline of Europe thus

got itself underway.

TSAR NICHOLAS II'S RUSSIA |

|

The Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905)

In its push to acquire additional territory, Russia had been reaching

eastward across Asia for decades and had arrived at the Pacific Ocean

by the mid-1600s. Over the next two centuries migrating into

Siberia were Russian fur traders, Cossacks, exiled criminals and

farmers escaping serfdom and looking for inexpensive land.

Resistance of the previous inhabitants, small nomadic communities

mostly, was problematic but not unsurmountable. So was the

resistance this Russian expansion drew from the Chinese emperor (who at

the time was hard pressed by the Taiping Rebellion and the Opium War

with Britain) resulting in the 1860 Treaty of Aigun, which favored

Russian claims in Manchuria.

But the biggest difficulty facing Russia would come from the Japanese,

who also had imperial interests in the same area. Under the

direction of the Japanese emperor, Japan had been both industrializing

and militarizing, using the very latest technology (acquired mostly

from Bismarck’s Germany) in the process. Their achievements were

stupendous ... very unexpected of a people who were not "White."

The Europeans would be startled by the readiness of the Japanese to

join them in putting down the Chinese Boxer Rebellion ... the Japanese

showing themselves to be as capable as any of the European powers in

their own imperial conduct.

Since the Vladivostok port on the Pacific was usable only during the

summer, the Russians had contracted with the Chinese the use of a port

(Port Arthur) further to the south in the Liaodong Province. This

brought them up against the Japanese who were interested in the same

region. The Japanese proposed an agreement in which Russia would

recognize Japanese control of Korea in return for Japan recognizing

Russian dominance in Manchuria. But discussions went nowhere

(meanwhile the Russians were building up their forces in the region).

Finally, in May of 1904 the Japanese conducted a surprise attack on –

and a blockade of – the Russian position at Port Arthur – and also

moved troops into Korea, taking that land for their own Japanese

empire. Bombardment of the Russians at Port Arthur continued

through the rest of the year, the Russians unable to break the

siege. Then much to the surprise of everyone (including the

Russians) at the beginning of January 1905, the Russian commander at

Port Arthur simply surrendered to the Japanese. Then in February

both sides (a total of 500 thousand men) met at Mukden, and after three

weeks of fighting the Russians abandoned their position there.

Finally, the Russian Baltic Fleet arrived in the area and at the

straits of Tsushima (the narrows between Korea and Japan) the two

navies met in late May ... again with disastrous results for the

exhausted Russian navy. The Russians were now ready to quit.

American President Teddy Roosevelt hosted a peace conference in

Portsmouth, New Hampshire (September 1905), in which the Russians got

off with only the loss of their positions at Port Arthur and on the

southern half of the Sakhalin Island. But the Russian humiliation

cut deeply nonetheless.

|

The Russo-Japanese War (1904

- 1905)

A modernized Japan challenged

Russia to battle – and Russia lost

Japanese troops marching through Seoul Korea - 1904

Japanese troops in

Manchuria - 1904

Japanese cannon during the

Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905

Japanese cannon during the

Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905

National Archives

Russians moving artillery

during the Russo-Japanese War

Japanese entering Port

Arthur

Japanese entering Port

Arthur

Russian trenches at the Battle

of Mukden (February 20 - March 10, 1905)

Japanese warships steaming

toward Tsushima to intercept the Russian fleet

Russian ships sunk at

Tsushima

Roosevelt meeting with the Russian and Japanese envoys

to negotiate the Portsmouth Treaty - 1905

|

The Russian Revolution of 1905

The timing of the conflict with the Japanese could not have come at a

worse time. Social agitation back in Russia had been building

since even before the war over the sense of gross mistreatment of the

Russian industrial worker by the new industrial lords. At the

same time these new industrial owners had been agitating for liberal

constitutional reforms. Thus labor unions had been organizing as

fast as liberal revolutionary societies ... all pressing for serious

overhaul of the Russian social and political system.

The Tsar however seemed unable to gauge the seriousness of this

agitation ... presuming that simple police action would suffice to keep

such radical tendencies in check. When in early 1905 a peaceful

demonstration led by a Russian priest and involving about 50 thousand

men and women in St. Petersburg was met by the Tsar’s soldiers who

killed hundreds and wounded over a thousand demonstrators (Bloody

Sunday) Russia exploded. Russia seemed to be spinning out of

control.

Workers’ councils (soviets) appeared everywhere and

liberals grew louder in their demand for reform. In October

(after the humiliating Portsmouth Treaty was signed with the Japanese)

a general strike was held across the country ... virtually shutting

down the entire Russian economy. The army had to be called out and was

put to work crushing brutally the protest movement. The Tsar

ultimately responded (the October Manifesto) by promising a number of

civil rights reforms ... and by offering a new Constitution and creating a Duma (legislature), so

eagerly sought by the liberal reformers. For the time being

things settled down.

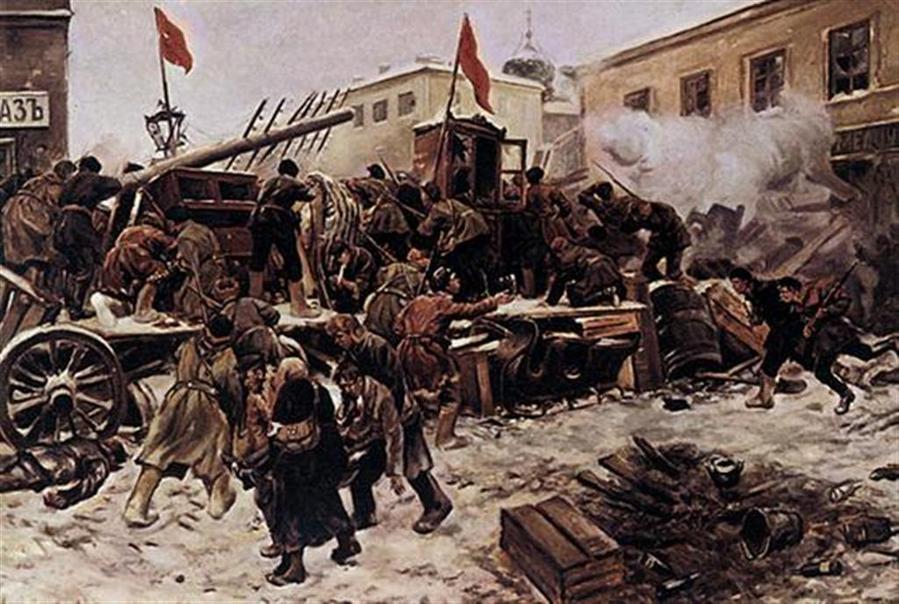

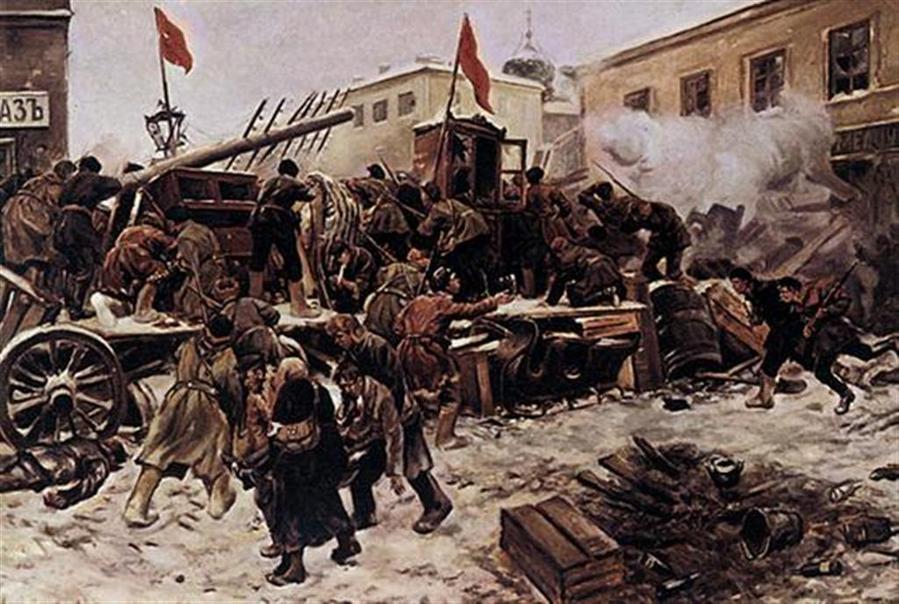

But pro-labor agitators (this included Lenin, who returned from Geneva for the occasion) saw

this backing down of the Tsar as a great opportunity to push for

Socialist reforms ... and scheduled a massive revolt for early

December. But despite the huge turnout of workers and their

soviet leaders to build street barricades in protest against the

government, they were met by soldiers who blasted the positions of the

protestors. Ultimately the workers' uprising failed ... and the

organizers decided to call off the protest. But feelings still

ran deep.

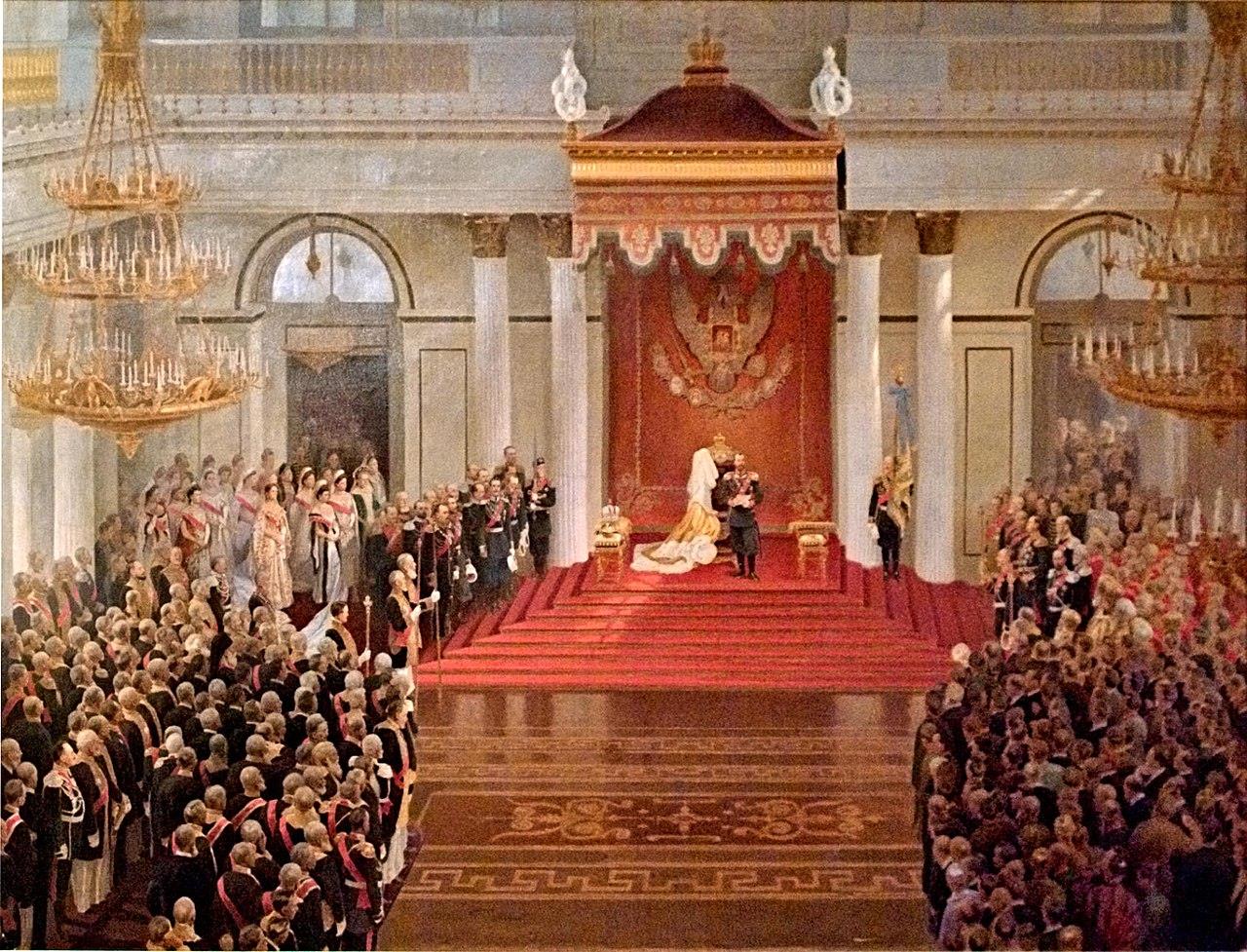

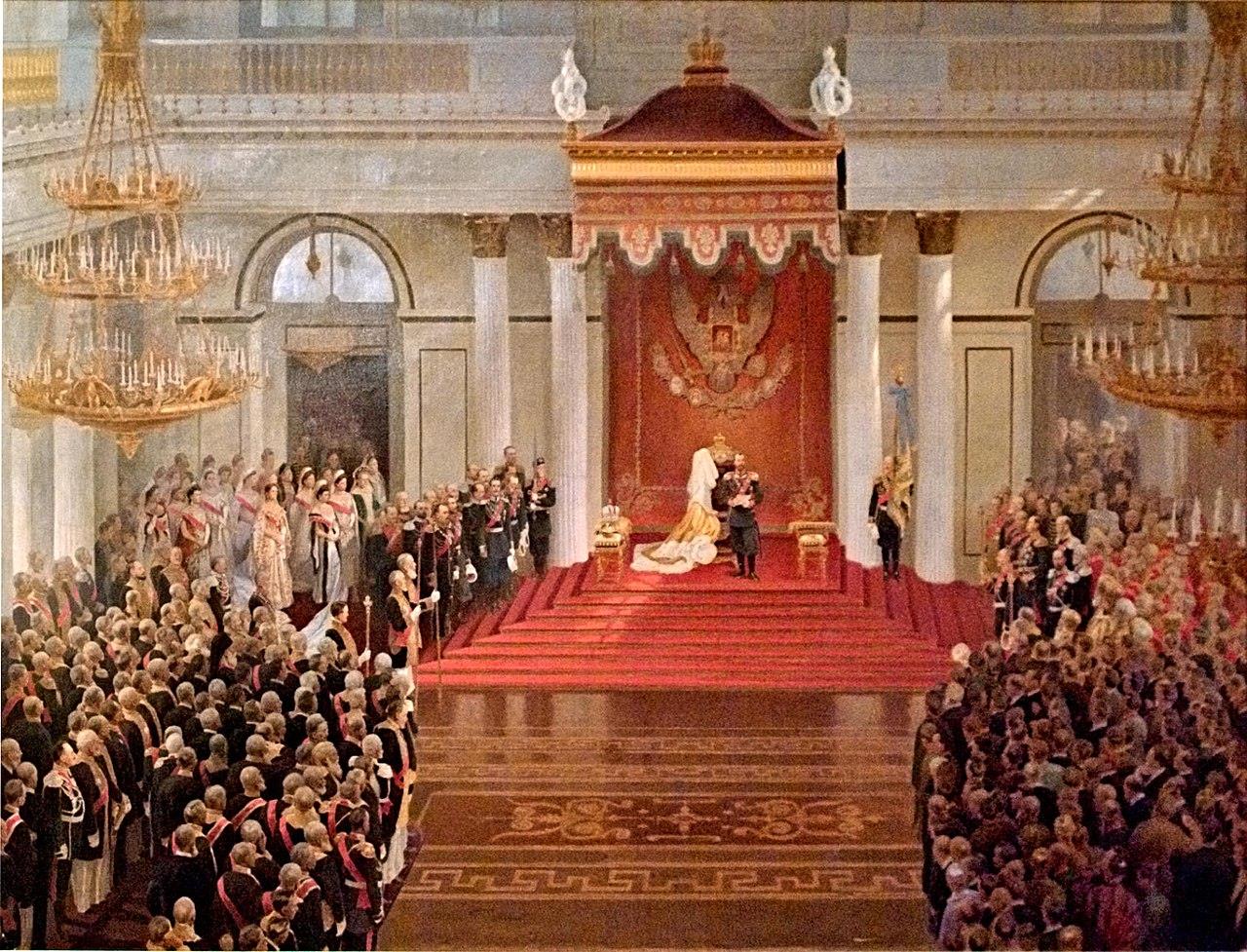

In 1906 the First Duma met in St. Petersburg ... but found the Tsar

highly reactive to pleas for deeper reform. To protect the almost sacred legacy of "autocracy," he instead reduced

the few rights of the Duma even further ... and then simply dismissed

the body. The next year (1907) the Duma again met, proving to be

even more hostile to the Tsar. It too was soon dissolved.

But before a Third Duma could meet the Tsar reshaped it so that it

represented only the more conservative members of the upper middle

class.

Serious reform would have to wait. As for the Tsar’s promised

civil rights reforms, those simply got dropped. Police repression

continued as it had before.

|

Bloody Sunday - January 1905 starts the rebellion

Soldiers firing on a huge crowd of Russians who had come to deliver a petiton to the Tsar.

Hundreds are killed (no one is sure of the actual number).

This action merely inspired more protesting throughout Russia

"Comrades, Workers and Soldiers

- Support Our Demands"

Women marching for governmental

reform as the protest movement gains strength

Russians celebrating Nicholas's October Manifesto (1905), leading to a new Constitution (1906)

Sergei Witte - by Ilya Repin, the Emperor's prime minister (1903-1906) who helped shape the 1906 constitution. Also Finance Minister (1892-1903) - helping design Russia's entry into the industrial world

Tretyakov Gallery - Moscow

An industrial workers' street barricade in Moscow - December 1905

An industrial workers' street barricade in Moscow - December 1905

Russian protest in Moscow in early December of 1905

Russian protest in Moscow in early December of 1905

Nicholas II and the Russian

Duma - April 1906

|

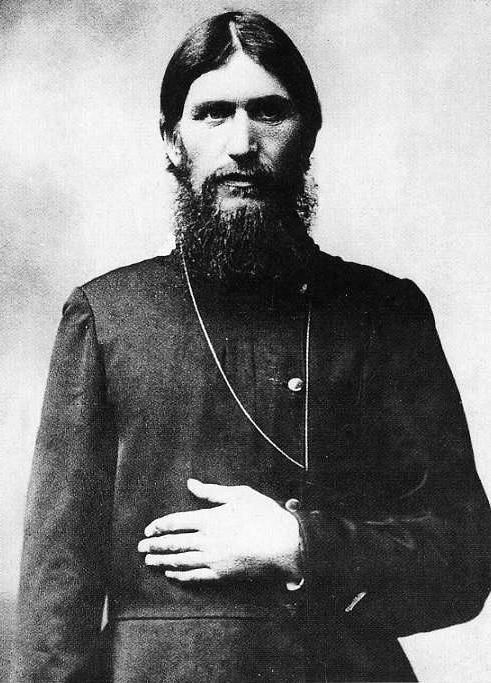

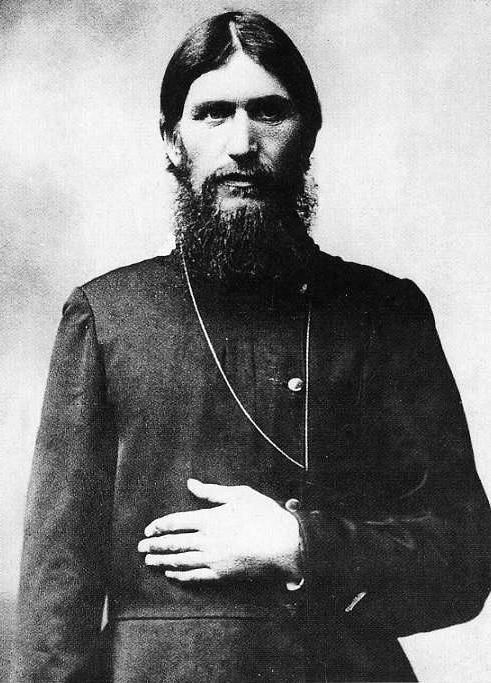

The Rasputin scandal

Clearly, the imperial family was losing touch with reality.

Tragedy stalked the halls of the Tsar’s Winter Palace. Adding to

the tragedy was the scandal created by the presence of the mysterious

Russian holy-man Grigori Efimovich Rasputin, who in 1907 had worked his

way into the imperial household on the claim that he had mystical

powers to heal the young prince Alexei, who suffered from the incurable

illness hemophilia (no ability to stop bleeding when injured).

Soon Rasputin became a regular celebrity within the imperial circle,

complements of the Tsarina, who was completely convinced of his divine

powers. Being a very hard-headed woman, she would also hear of

none of the rising complaints about how Rasputin’s frequent presence in

the imperial court was causing highly damaging rumors to spread wildly

among the Russian people.

Little by little opposition to him began to brew within the imperial

court. Yet as time went on, Rasputin – with the support of the

Tsarina Alexandra – seemed to grow in influence in the matters of state

... especially with the departure in August of 1915 of the Tsar for the

front during the "Great War" (World War One, which had been underway

since August of 1914).

Resentment among the men of the imperial court grew so great that

finally in January 1916 a small group of them plotted his murder ...

which proved not to be as easy as they had hoped (or so the legend

goes). But indeed finally he was gone. But by this time the

Great War was giving Russia even bigger issues than Rasputin. |

Nicholas and Alexandra

Grigori Rasputin - mystical

adviser to the Tsarina

Grigori Rasputin - mystical

adviser to the Tsarina

(the seedier side of imperial

culture)

|

The Young Turks

With the power of the Turkish sultanate fading away, the Young Ottomans

formed and reformed their secret political organizations, adding

medical students and military officers to their rolls. They

eventually created a political union, the Committee of Union and

Progress (CUP) which in 1902 and 1907 held its first and second

congresses (in France).

Then in 1908 the military wing, beginning to be termed the "Young

Turks" – under the leadership of "the three pashas" (Talaat Pasha,

Enver Pasha, and Djemal Pasha) – marched on the capital at

Constantinople (Istanbul) and forced the sultan to restore the

Constitution of 1876. While he agreed, he seemed to be

encouraging reactionary elements in the military, who in 1909 attempted

a counter-revolution against the Young Turks. The effort failed,

and Abdül Hamid was forced to abdicate and go into exile. His

brother, Mehmed V, was installed as sultan in his place. But

Mehmed had no real power of his own. At this point the Young

Turks were the actual governors of the decaying Ottoman Empire.

|

The one ugly spot in the

cultural picture is the decaying Ottoman dynasty in Turkey. But a group of "Young Turks"

(mostly military) are planning to take control and bring Turkey up-to-date

through a process of "modernization" (mostly following Prussian

Germany's lead)

Abdul Hamid II - Ottoman

(Turkish) Sultan - 1876-1909

Abdul Hamid II - Ottoman

(Turkish) Sultan - 1876-1909

An elderly Abdul Hamid

II

An elderly Abdul Hamid

II

Mohammed (Mehmed) V - Ottoman

Sultan 1909-1918

The Young Turks

Mehmed Talaat Pasha - Minister

of the Interior (1909-1917)

Grand Vizier of the Ottoman

Empire (1917-1918)

Ismail Enver Pasha - Turkish

General and Minister of War (1913-1918)

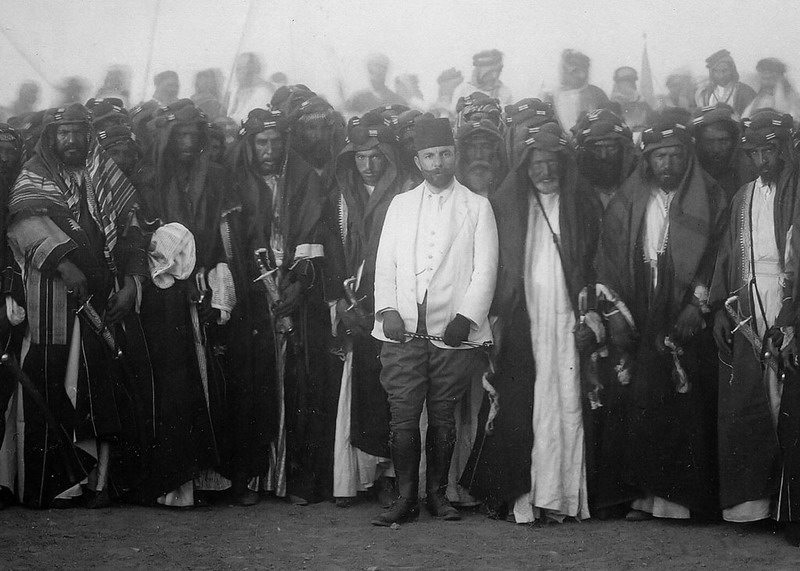

Ahmed Djemal (or Cemal)

Pasha,

Commander of Constantinople,

Minister of Public Works, Minister of the Navy and General (1913-1918).

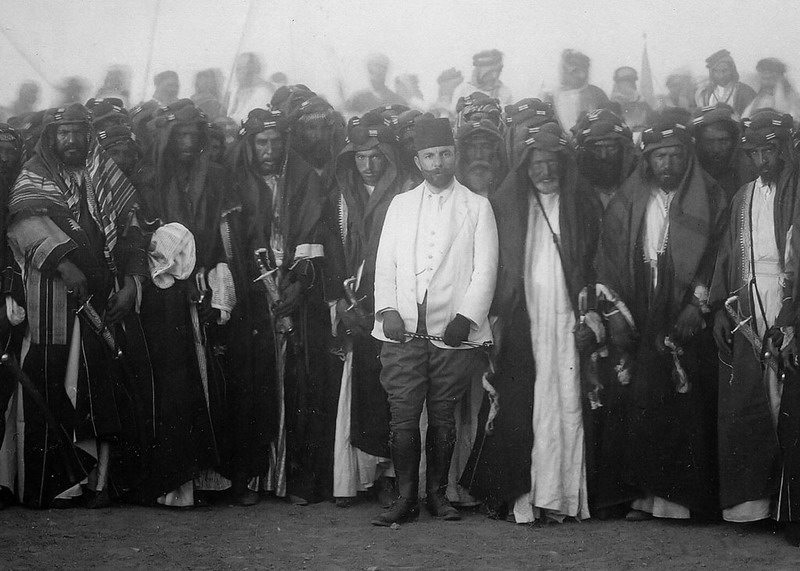

Prominent Young Turk:

One of the "Three Pashas"

ruling the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1918

Ahmed Djemal and Arab leaders

at the completion of a dam

on the Euphrates River south of Baghdad

THE BALKAN WARS AS PRELUDE TO THE COMING "GREAT WAR" |

|

Rumania (after 1975 "Romania")

In close cooperation the Greeks, the Wallachians also rose up in revolt

against the Turks in 1821, demanding number of political reforms ...

though expressing continuing loyalty to the Sultan. Here too

infighting among the Wallachians made it relatively easy for the

Ottomans to restore Turkish order. Another attempt occurred in

1848, along with the general liberal upheavals that shook Europe that

year. This united the province of Moldavia with Wallachia to form

the idea of a united "Rumania." But the effort came to nothing

... until after the Crimean War when in 1859 electors from both

provinces voted for a single leader as Rumanian prince (within the

Ottoman Empire). In 1866 he was forced out and replaced by prince

Carol I of Rumania (of the Prussian house of Hohenzollern).

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878

In 1875 peasants in

Herzegovina (just to the west of Serbia) rose up in revolt against the

heavy Turkish taxes ... and the revolt soon spread around the

Balkans. The Turks reacted violently, their slaughter being

especially heavy among the Bulgarians living just north of the

Constantinople region. This not only shocked the Europeans, it

drew the Russians into the melee as a champion of the persecuted

Bulgarians. Russian intervention no doubt was also motivated not

only by the desire to recover territories on the Black Sea lost during

the Crimean War, it was also inspired by the eternal Russian dream of

securing a foothold on the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Turks were soundly defeated. As a result, in the Treaty of

San Stefano (1878), the Turks lost sovereignty over considerable

sections of Balkan territory. Not only was Turkey forced to

acknowledge the full independence of Rumania, but also Serbia and

Montenegro.

Bulgaria

To the Russian mind, even more important was the fact that the Slavic

principality of Bulgaria (under the Bulgarian prince Ferdinand I) also

was founded as a result, stretching across the southern reaches of the

Balkan Peninsula just above Greece. But the British and the

Austro-Hungarians were afraid of such an extensive client state of

Russia and forced the replacement of the San Stefano treaty with the

Treaty of Berlin, which recognized only a smaller Bulgarian

Principality. This was designed to prevent the creation of a

strong Slavic state in the Balkans, presumably playing to the interests

of Russia ... which the other European states wanted to avoid at all

costs. The Bulgarians living in Macedonia were thus left out of

the new Bulgarian state ... a matter that would soon become the cause

of serious strife among the emerging Balkan nations.

At the same time the British were accorded the right to occupy the

strategic island of Cyprus (protecting the sea route passing nearby on

its way to the Suez Canal in Egypt) and Austria-Hungary was given the

right to "administer" the Ottoman territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In theory Bulgaria was still under Ottoman authority, but it acted

rather like an independent nation. Finally in 1908 Bulgaria

declared its independence as the Kingdom of Bulgaria with Ferdinand now

designated as Bulgarian Tsar.

The Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913

There were two conflicts that broke out in the Balkans, the first

(1912) between Turkey and a coalition of newly independent Balkan

states (the Balkan League of Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia),

the second (1913) a war within the community of Balkan states, pitting

Greece and Serbia against Bulgaria in a dispute about the dividing of

Macedonia as a result of the first war. Bulgaria was unhappy

about the way Greece and Serbia took the largest portions of Macedonia

... and decided to invade the area to incorporate Macedonia into

Bulgaria. Seeing Bulgaria thus distracted, Rumania – which had

stayed out of the first war – decided to launch its own offensive

against Bulgaria. And Turkey struck back at Bulgaria as

well. The end result was the dividing up of Macedonia between

Serbia and Greece, and the loss of Bulgarian territory to the Greeks,

the Turks and the Rumanians.

The major European powers had decided to stay out of the first war,

fearing that their intervention would only complicate further a

diplomatic standoff that was building among the larger powers

themselves. In the second war the major powers got indirectly involved,

though not necessarily out of a desire to do so. The net result

of this second war was the delivery of a huge blow to Russia, because

of the Russian support of Serbia – which in turn had driven its former

Bulgarian "protectorate" into the waiting hands of the Germans.

This war also further deepened the divide between Serbia and its

neighbor to the north, Austria-Hungary, which – with Germany – saw

Serbia as a new Russian dependency and a possible ally in Russia’s

quest for a forward position in the Balkans.

Tensions were building fast. It would take only a small spark to

set off a huge military conflagration. That spark was about to

occur. |

1912 - The Balkans before

the Balkan War

April 1913 The Balkans after

the First Balkan War

April 1913 The Balkans after

the First Balkan War

>Greek Artillery during the

Balkan Wars – 1912

Turks captured by Greeks

at the Battle of Giannitsa – October 1912

Turks captured by Greeks

at the Battle of Giannitsa – October 1912

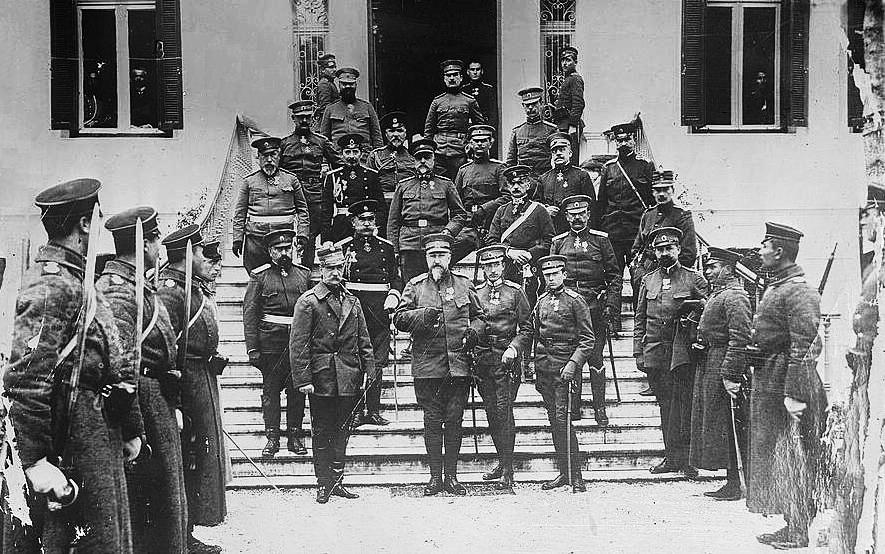

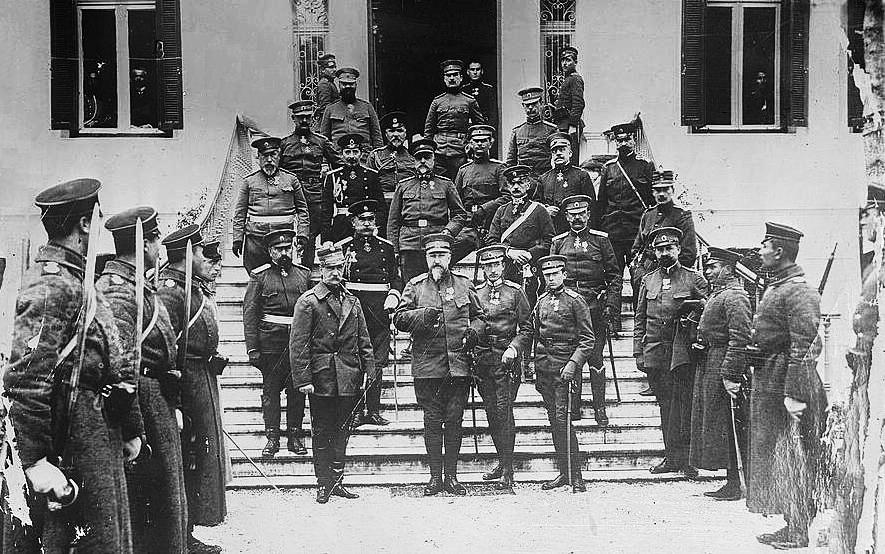

King George I of Greece visits

the Bulgarian Tsar Ferdinand in the headquarters of the Bulgarian army in the city of Thessaloniki

during the latter's visit there during the First Balkan War (December 1912).

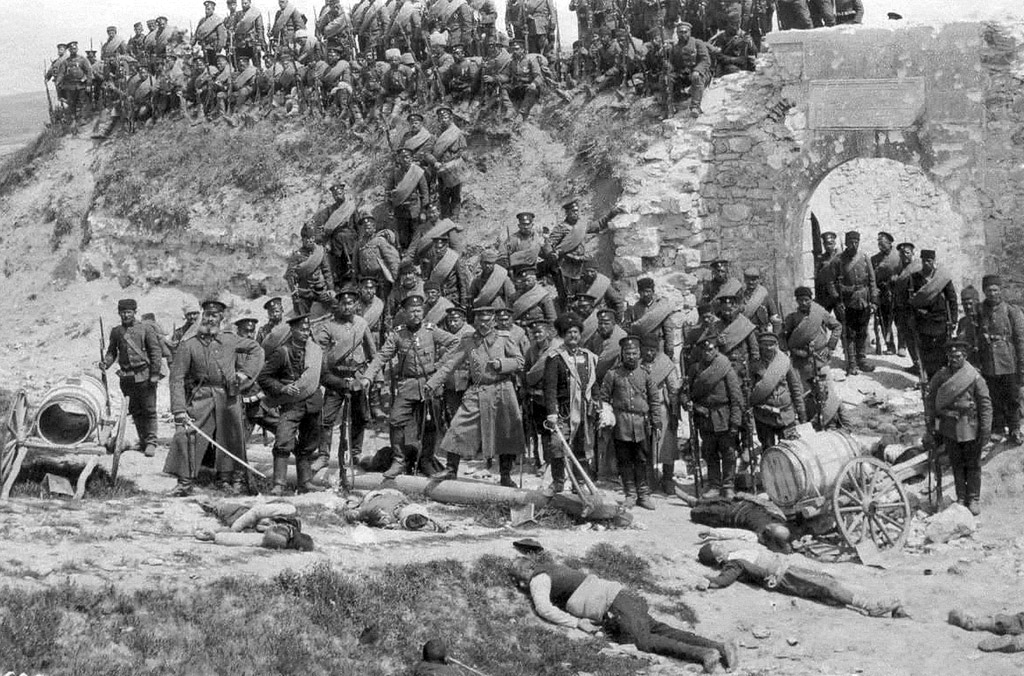

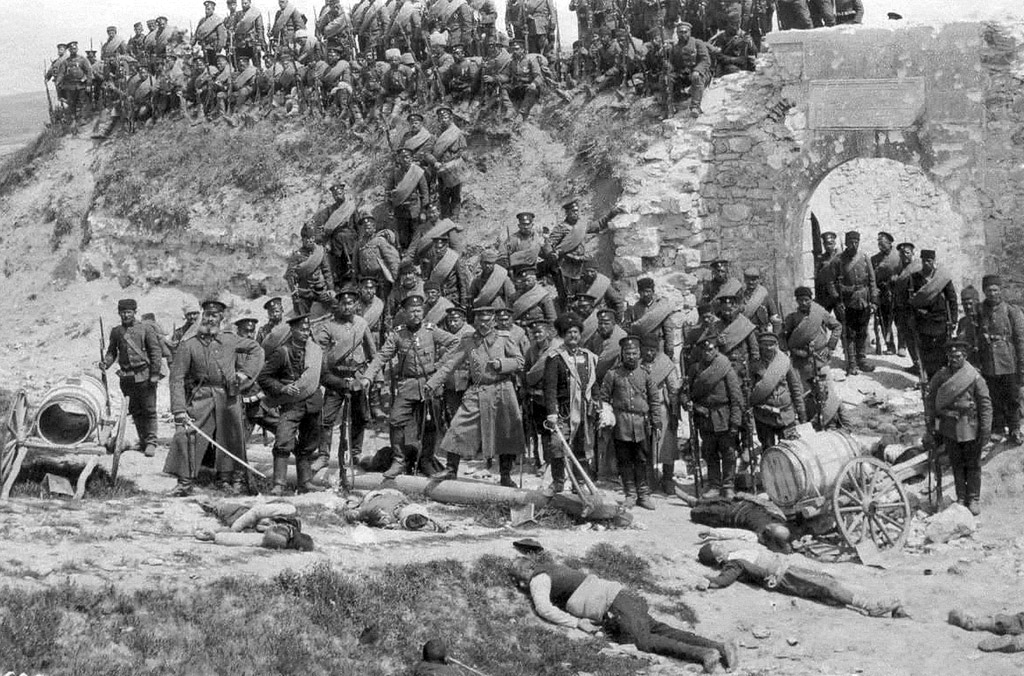

March 1913 - Bulgarian soldiers

(and Turkish dead)

at the Awaz Baba Fort outside Adrianople (Edirne)

More soldiers died of disease

than through military action

More soldiers died of disease

than through military action

Territorial changes in the

Balkans due to the 2nd Balkans War (April-July 1913)

Territorial changes in the

Balkans due to the 2nd Balkans War (April-July 1913)

GROWING TENSIONS AMONG THE MAJOR EUROPEAN POWERS |

The

age of imperialism had conveniently served to direct rising national

ambitions infecting the European continent away from Europe

itself. But with the near completion of the global land grab by

the end of the 1800s it was perhaps inevitable that these European

ambitions would turn to a question closer to home: the breakup of the

Ottoman Empire and the territories it would free up for the

taking. This matter was too close to home to keep it rather

abstract in principle. With this contest right in its back yard

the danger of this turning into a brawl within Europe itself was

great. It would require great diplomatic skill to prevent this

contest from getting out of hand. But sadly, such skill was

largely missing among those who led these European major powers.

The growing system of opposing alliances

The nationalist passions were heating up. The French had been

unrelentingly bitter about their loss to Germany of Alsace and Lorraine

in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. To the French it was a matter of

huge principle to get these lands back. Sensing the danger, in

1872 Bismarck promoted the creation of the Dreikaiserbund

(Alliance of Three Emperors) made up of Germany, Russia and Austria as

a counter to French ambitions. But when Russia and

Austria-Hungary found themselves in opposition over the breakup of the

Ottoman Empire, Bismarck decided to drop Russia and stay with his

fellow German Austria. Thus in 1879 he formed the Dual Alliance

between Germany and Austria-Hungary ... and in 1882 he extended this

alliance to include Italy, giving the alliance now the designation as

the Triple Alliance. Italy was not a particularly enthusiastic

partner. But necessity (Italy was fuming over the French seizure

of Tunisia) seem to dictate the relationship.

In the meantime relations between France and Russia were warming up ...

mostly out of concern over the buildup of German military power and the

growth of Austria-Hungary’s interests in the Balkans. By the

1890s this French-Russian relationship had turned itself into a basic

understanding or entente, including the plans for military

cooperation. Basically the entente was an agreement that if

either France or Russia were attacked by a member of the Triple

Alliance, the other would come to the aid of its partner.

At first the British found themselves caught in the middle of this

growing split. Britain approached the alliance matter

cautiously. But concern by both Britain and Japan over Russian

involvement in Asia brought Britain to sign an alliance with Japan in

1902. Then as Wilhelm grew bolder in his development of the

German navy, British nerves began to fray ... and the British decided

to enter into an anti-German entente with their long-time former

opponent, the French, resulting in the Entente Cordiale of 1904.

Finally, with Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, the British

concern for Russian activities in Asia dwindled to the point that

Britain was willing to enter yet another entente, this time with

Russia. Thus in 1907 the Triple Entente of Britain, France and

Russia entered into effect. Three years later the Japanese and

Russians came to an agreement ... and Japan thus decided to ally with

the Triple Entente.

The first Moroccan crisis (1905-1906)

Rising

tensions among the European players of the nationalist game nearly

turned to blows exchanged between Germany on the one hand and France

and Spain (backed by Britain) on the other over the status of

still-independent Morocco. Actually, Morocco's independence came

in the form of "protection" offered by France and Spain to Morocco in

1905 … done without any "consultation" with Germany … ignoring an

earlier 1881 agreement which had included Germany as one of the

guarantors of the Moroccan status quo. Wilhelm was not only

insulted that Germany had been left out of the new arrangement … but

was seeing all this as simply another effort of France and its ally

Britain to keep Germany from its natural "place in the sun." Thus

in 1905, Wilhelm personally sailed to Morocco to offer the Moroccan

sultan the same "protection."

A huge diplomatic crisis thus resulted. To avoid a mounting

confrontation, it was finally decided to bring the matter early the

next year (1906) to an international conference held at Algeciras in

Spain (attended also by the U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt). The

conference confirmed the sovereignty of Morocco, but in fact allowed

for both Spain and France (not Germany) to serve as the protectors of

that sovereignty. Germany was still excluded from a role there.

Bosnia-Herzegovina (1908)

As

tensions built in the Mediterranean, without any warning things

exploded over on the other side of Europe … when in 1908

Austria-Hungary simply announced the annexation of the former Turkish

territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina. But land-locked Serbia had also

been contemplating the same action … in order to extend its own borders

all the way to the Adriatic Sea (part of the Mediterranean Sea).

Serbia was furious.

But this land grab also widened the divide between Austria and Russia

(the latter being a strong supporter of Serbia), caused some

consternation with Austria’s ally Germany (which had not been consulted

prior to the event), and forced France and Britain (both neither in a

position to help Serbia nor willing yet to help Russia) to stand off,

very unhappy over the event. And as for Turkey, it was rather

content to receive monetary compensation from Austria for its loss of

these two distant provinces.

The second Moroccan crisis (1911)

Morocco

was not doing well under French and Spanish protection. The

sultan’s finances were in crisis mode and unrest among the Moroccans

was building. When rebellion broke out in Fez against the Sultan

in April of 1911, the French moved troops to Morocco to "protect its

citizens in Morocco" and to support the Sultan. This upset

Wilhelm greatly, who saw this as simply a ploy for the French to add

Morocco to their North African empire. Wilhelm countered the

French move by sending the German gunboat Panther to Morocco "to

protect German citizens."

This in turn angered deeply the French and Spanish ... and also the

British who were lining up more closely with France (the "Entente

Cordiale"). Consequently, France (with British backing) refused

to be intimidated. Ultimately, Wilhelm backed down.

Part of the dynamic in this incident was that Germany had been

challenging British supremacy with its rapid own development of a

German navy, increasing British nervousness about Wilhelm's

intentions. Britain, being an island, was always very sensitive

about international naval matters.

On the other hand, Wilhelm, in being forced to back down from his

ambitions in the Mediterranean, chose to see this episode as simply

more German "encirclement" ... and began looking to expand Germany's

own diplomatic alignments to counter the close relationship of Britain,

France and Spain.

Thus

it was that things were pushing quickly toward the horrible events of

1914. Nationalists of all the major European countries seemed to

want a street fight of some kind to finally settle the matter of

Europe’s power alignment. But what they failed to realize was

that such a fight was not destined to be merely an afternoon sporting

event. The powers seemed so evenly balanced at this point that

once underway such a conflict would simply stalemate itself into a

long, unrelenting bloodletting – the kind that could result only in a

huge loss of political strength by all parties, the kind that would in

the end (should there ever be an end) resolve nothing. But

passions at this point had greatly overridden cool logic.

A war now seemed inevitable.

|

The First Moroccan Crisis – 1905

Kaiser Wilhelm on parade in Tangier - 1905

El-Hadj el-Mokri, Moroccan Ambassador

to Spain, signs the treaty at the Algeciras Conference allowing France to patrol

the border with Algeria and Spain to police Morocco (April 7, 1906).

The Agadir (or Second Moroccan) Crisis

- 1911

Loading of French artillery

at Rabat, Morocco - 1911

Grébert, photographer,

Casablanca

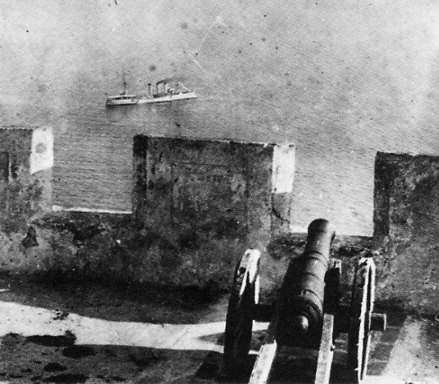

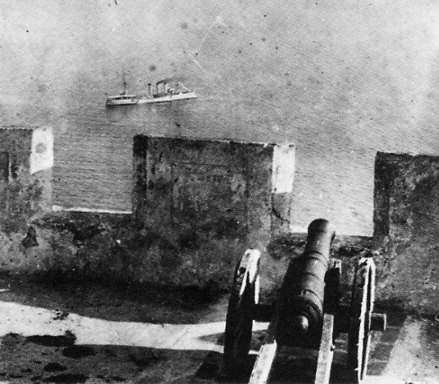

The battlements at Agadir

Morocco - with a German gunboat Panther in the harbor (July

1911)

The battlements at Agadir

Morocco - with a German gunboat Panther in the harbor (July

1911)

WAR FEVER REFUSES TO COOL DOWN |

War

fever seemed to be intensifying everywhere. Nationalists of all

the major European countries seemed to want a street fight of some kind

to finally settle the matter of Europe’s power alignment.

But what they failed to realize was that such a fight was not destined

to be merely an afternoon sporting event. The powers seemed so

evenly balanced at this point that once underway such a conflict would

simply stalemate itself into a long, unrelenting bloodletting – the

kind that could result only in a huge loss of political strength by all

parties ... the kind that would in the end (should there ever be an

end) resolve nothing. But passions at this point had greatly

overridden cool logic.

A war now seemed inevitable.

|

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| |

The path to world war

The path to world war

The Balkan Wars as prelude to the

The Balkan Wars as prelude to the Growing tensions among the majo

Growing tensions among the majo War fever refuses to cool down

War fever refuses to cool down