13. "THE GREAT WAR" (WORLD WAR ONE)

1914

1914

Europe in 1914

Europe in 1914

The spark that set off the fire: Sarajevo

The spark that set off the fire: Sarajevo

(June 28, 1914)

Germany invades Belgium in order to

Germany invades Belgium in order to

seize Paris

With Germany's invasion of Belgium, the

With Germany's invasion of Belgium, the

English enter the War

The Turks come into the war on

The Turks come into the war on

Germany's side

The Germans drive on into Northern

The Germans drive on into Northern

France - August-September 1917

Simultaneous clashes on the Eastern

Simultaneous clashes on the Eastern

Front

With missed objectives: The war takes

With missed objectives: The war takes

on a lasting quality

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 78-82.

THE

SPARK THAT SET OFF THE FIRE: SARAJEVO |

|

The assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand

(June 28, 1914) The absorption of Bosnia-Herzegovina by Austria was by no means a finished matter. Serbia was in no mood to accept this development and Austria knew it had work to do to complete the absorption of these Balkan provinces. When in June it was announced that the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand (acting on behalf of his 84-year-old uncle, the emperor Franz Joseph) would be visiting Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, a radical group of Serbian nationalists (including even members of the Serbian government) planned his assassination. They wished to disrupt Austria’s plan to create a new Triple-Monarchy (Austria, Hungary and now also a Slavonic state) under the Austrian emperor’s authority. Austria’s plan would have ended the Serbian dream of an independent Greater Serbia (reaching down to the Adriatic Sea). Somehow Austria needed to be stopped. But the plot nearly failed, but only nearly, for by accident one of the plotters (who was actually on his way away from the proposed action) was able to shoot the Archduke and his wife as they passed by him … after having taking an "alternate" route – ironically out of the fear of just such an act. But the assassin was quickly caught … and identified as a Serbian nationalist. |

Bildarchiv und Porträtsammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek

Austrian Archduke Francis

Ferdinand and his wife Sophie just before their assassination

THE

NATIONS MOBILIZE FOR WAR |

|

Austria’s declaration of war on Serbia

At this point Austria wanted to destroy Serbia, but needed German backing. Wilhelm was reluctant to get involved in such a tangle but also knew that German support was vital in keeping the Austrian-Hungarian empire from falling apart. He had to support Austria. Aware of this backing, the Austrian cabinet placed extremely heavy demands on Serbia to allow Austria to take over the search in Serbia for the Serbian criminals (presuming a Serbian refusal, and thus in effect precipitating the war sought by Austria). The Serbian government itself had authorized no such act … and tried to meet the terms of an outraged Austria. Thus most of Austria's demands were agreed on by the Serbian government. But Austria insisted that not most – but all – of the demands be met by Serbia. When Serbia stalled, Austria decided that it had the justification it needed … and on July 28 declared war on Serbia. Austria supposed that this would remain a quick, local war, as most of the wars in the Balkans had been. But Austria foolishly had failed to take note of the fact that things were very different in the European diplomatic world at this point. Russia joins in

It was now Russia’s turn to decide what to do. Russia was not only the protector of Serbia, it saw in this outbreak of war the opportunity to take advantage of the crisis to seize Constantinople and complete its dream of its own port with direct access to the Mediterranean. But Russia was not really prepared for a major war, and Tsar Nicholas was well aware of this fact. Yet he could not hold back his own ministers who wanted war nonetheless. They demanded a general mobilization. Nicholas knew well that this would constitute a declaration of war, and by the terms of the Dual Alliance would automatically bring Germany into the war as well. But he finally gave in to his ministers and on July 29 the Russian cabinet called for mobilization. A few hours later he received a conciliatory letter from his German cousin Wilhelm. But it was too late to call off the mobilization. Russia was at war. Germany joins in

Germany reacted immediately to the news of the Russian mobilization with a demand that the Russians immediately back down, and declared war (August 1) on Russia when Russia failed to do so. Germany then sent a letter to France demanding to know whether or not France was intending to stay out of the conflict, received an ambiguous reply, and thus declared war on France (August 3). Italy initially chooses to stay out of the conflict

Most wisely, Italy declined to honor its treaty with Germany and Austria-Hungary … because it had agreed to act in accordance with the treaty only when it was a matter of national defense – not offense, as clearly was the case for Austria (and Germany also for that matter). Italy thus stayed neutral … at least for a while. Turkey joins the German-Austrian side

Turkey, meanwhile, having no formal commitments to either side, was at first unsure of where it stood in this new crisis. It looked to Britain as a friend (Britain had earlier defended Turkey against Russian expansion) … but with Russia now a British ally, this confused matters a bit. Also, the Young Turks were very impressed with German military technology and general order, although Germany's alliance with Turkey's problematic neighbor Austria complicated matters here as well. But finally, Turkey chose to enter the war on the side of Germany … although it had little to offer its new allies by way of military support – at least not at first. The papacy stays neutral … and humanitarian

Giacomo Chiesa had just been voted pope as Benedict XV in 1914 – in the very days that the war first broke out. He immediately declared the Catholic Church to be neutral in this nationalist contest. Indeed, pope Benedict tried on two occasions (1916 and 1917) to formally mediate the conflict ... but was rejected by both sides of the contest. Nationalist fervor hugely outranked the religious – even Catholic – loyalties of fired-up Europeans … at least those of the political leadership of the nations involved. Meanwhile, Benedict undertook to offer humanitarian aid to both soldiers (captured and/or wounded) and hungry civilians. |

The Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum.

Library of Congress

The Imperial War Museum

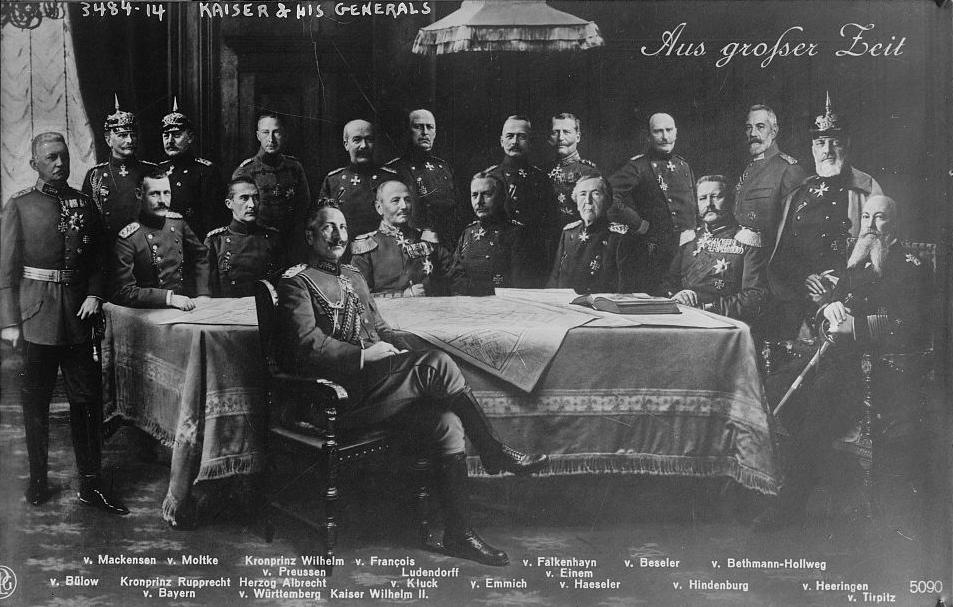

von

Moltke

von

Moltke  von

Bulow

von

Bulow

The Imperial War Museum

IN

CONFORMITY TO THE SCHLIEFFEN PLAN, GERMANY INVADES BELGIUM IN

ORDER TO

SURROUND AND SEIZE PARIS AND THE FRENCH

ARMY |

United States Military Academy

|

The Western Front

Germany supposedly was well-prepared for just such a conflict. According to a military plan (the Schlieffen Plan) drawn up years earlier in the expectation that war would eventually occur again between Germany and France over the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, the Germans had designed plans to send German troops hurriedly through Belgium in order to grab Paris (located in the north of France, not far from the Belgian border) before the French had a chance to mobilize their war machine. This was basically what had happened in Prussia's war with France back in 1870. And Wilhelm knew that with Paris under German control, France would be unable to offer any resistance. Wilhelm also knew of course that sending his troops through Belgium would be in total violation of that country's neutrality (Belgium had been purposely established as a buffer zone amidst Germany, France, the Netherlands and Britain). Violating Belgian neutrality would automatically mean war with Britain. But Wilhelm expected the German grab of Paris to happen so quickly that the war would be over before the British could get mobilized. But what Wilhelm had not counted on was the stiff resistance offered by the Belgians … and the rapidity of the French response to a call to arms in defense of France's borders (with France now also allowed by terms of the Belgian treaty to place its defenses further to the north, even in Belgium, against the German invaders). Thus the Schlieffen Plan failed to function as anticipated. The German effort soon slowed down … despite the horrible treatment the Germans gave the Belgians for their resistance, both military and civilians – immediately earning the Germans the term "Huns" because of their horrifying brutality. And indeed the British were also quick to act … sending part of their army, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), to France and Western Belgium to help slow down the German momentum. And indeed, by the end of August, the German invasion of northern France had come to a full halt – across a long line of action reaching from the Rhine River in the East to portions of western Belgium in the West … and just north of the Paris suburbs. Paris was thus saved. And there, along that long battle line, the action would bog down completely. In fact, over the next years this battle line would hardly budge one way or the other … no matter how many men (millions were) sent to try to break through this highly defended line of deep trenches, barbed wire, machine guns, cannons, poisonous gas … and multitudes of soldiers. |

S.L.A. Marshall, The American Heritage History of World War One, New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1982, p. 47

The Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum

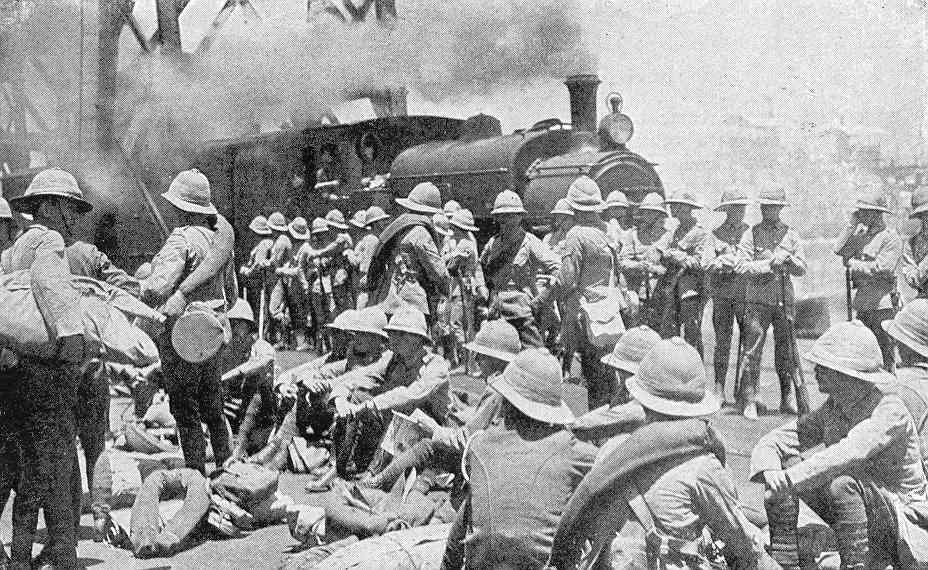

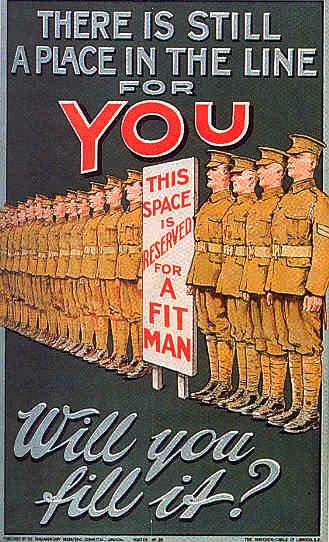

WITH

GERMANY'S INVASION OF BELGIUM, THE BRITISH ENTER THE

WAR |

Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum

Kitchener went down with the cruiser Hampshire in June of 1916; Lloyd-George succeeded him as British Secretary of War in early July

THE

TURKS COME INTO THE WAR ON

GERMANY'S SIDE |

The Imperial War Museum

German Information Center

AMERICA

STAYS NEUTRAL |

THE

GERMANS DRIVE ON INTO NORTHERN FRANCE – AUGUST

- SEPTEMBER 1914 |

The Imperial War Museum

MEANWHILE,

SIMILAR CLASHES HAVE BEEN TAKING

PLACE ON THE EASTERN FRONT |

| On

the other hand, the long battle line reaching in the East from the

Baltic Sea in the North to the Balkan Peninsula in the South, was much

less a permanent matter, moving back and forth as pressure was applied

here and there: Germans against Russians in the North, Austrians

against Russians in the center of the line, and Austrians against Serbs

in the South. Although Russia had a much larger army than the

Germans and Austrians, and although Germany was deeply committed to

action on the Western Front in France and Belgium, the Russians did

very poorly in their contest with the Germans. At one point early

in the conflict (at Tannenberg at the end of August) a Russian advance

turned into a Russian defeat when a huge Russian army was skillfully

surrounded and forced to surrender to its German opponents. Russia still had more men to bring into the war. But this initial defeat would be merely the beginning of many troubles the Russians would experience in continuing a war they now had no idea of how to pull out of without a huge loss of national pride. In the central part of the line of engagement, the Russians were facing an Austrian army of equally inferior quality, in great part because of its multinational character. Here the war bogged down along a line that reached from the Carpathian Mountains in the south to Silesia in the north, and efforts of both sides to move the line proved to be dismal failures. In the South, the Serbs were able at first to hold back the Austrians. But the Serbs were vastly outnumbered by the Austrians in numbers of troops and weapons … and bit by bit Serbia was forced into a step by step retreat in the Balkans. |

Marshall, p. 67

National Archives

WITH

MISSED OBJECTIVES, THE WAR TAKES ON A LASTING QUALITY |

200,000 French soldiers died in the first month of the war alone. By October, 2 months later,

the glamor of war is gone. The peasants don't even look up from their work as the soldiers go by.

Marshall, p. 78

into an unmoveable, deadly stalemate - October-November 1914

U.S. Military Academy at West Point

THE BATTLE AT SEA |

The German U-9 submarine

that on September 22, 1914, sank 3 British cruisers:

the Aboukir, the

Cressy

and the Hogue

The German battleship

Scharnhorst,

flagship of the German squadron that sank three British warships on November 1, 1914.

The Scharnhorst was sunk in a battle with a British fleet on December 8

British boats being sent out to pick up the survivors of sunken ships during the battle of the Falkland Islands – December 8, 1914

Go on to the next section: 1915

Go on to the next section: 1915