|

|

The ancient Greek political-intellectual legacy The ancient Greek political-intellectual legacy Greek origins Greek origins Early philosophical development: Materialists versus Mystics Early philosophical development: Materialists versus Mystics

Athens' rise to glory Athens' rise to glory Athens' political-social-moral decline Athens' political-social-moral decline The Big Three: Socrates, Plato and Aristotle The Big Three: Socrates, Plato and Aristotle The textual material on the page below is drawn directly from my work,

A Moral History of Western Society, © 2024, Volume One, pages 31-52. |

|

| It

is of vital importance to note that America's "Founding Fathers" who

gathered in Philadelphia during a very hot summer in 1787 to draft a

new Constitution uniting their thirteen1

newly-independent states were college educated – or at least

self-taught in the intellectual areas that a college education would

have included – and were therefore well-informed about the ancient

Greeks … and the political and intellectual lessons to be drawn from

Greek history. And it was a huge legacy … highly instructive of

both the good – and the bad – in any society's political and

intellectual development. Thus this Greek legacy would factor

hugely in how those that were called to put together a new American

Constitution would finally design or "frame" this most fundamental

American political foundation. They knew to build on the positive

part of the Greek – especially the Athenian – legacy … and avoid the

horribly negative parts of that same legacy. At the heart of that legacy was the immense intellectual energy that a large number of Greek individuals were able to generate. Greek scholarship brought Greece forward out of its original neolithic (farming and animal herding) world … and into a highly civilized world – urbanized on the basis of the very independent Greek city-states. Such development sparked deep inquiry into a newly awakening world … and what that meant to the Greeks in terms of the social "progress" they were seeking to achieve. But unfortunately, that same highly intellectual spirit would also come to lead the Greeks, notably the leading Greek city-state Athens, into very self-destructive political rationalizing. Tragically, the Athenian "Sophists" (wise ones!) of the 400s and 300s BC used their intellectual gifts to lead a very gullible Athenian citizenry to take up very self-destructive political causes … ones that led to a series of totally ruinous wars. Thus the cleverly rational Greek Sophists demonstrated to the American Framers the dangers of human "reason," always clever – but hardly the kind of Truth that elevates life. After all, half of these Framers were lawyers, and already knew that a very convincing rational argument laid before a jury on behalf of a client of theirs was simply the business they offered their clients. For the jury, deciding the actual "Truth" of a dispute involving a "rational" defense put before them by opposing – but equally clever – lawyers was a very delicate, often very uncertain, matter. Thus the Framers knew very well that Reason itself never equaled Truth. Reason merely advantaged one side of a dispute over its opponents. The actual truth of things thus always stood above – and often well beyond – human reason. The Greeks proved that quite clearly. "Democracy" as Greece's great legacy. Undoubtedly when Greece is remembered today as a major contributor to Western civilization it is in the area of "democracy" that Greece – but especially Athens – is mostly noted. But actually, for almost two thousand years, the Greek concept of "democracy" dropped from view or discussion ... and for good reasons. Democracy or rule by the people (the Greek demos) is an almost sacred concept today ... but one not well understood by those very ones today loudest in their promotion of the glories of democracy. The way they go at this matter comes from their instincts favoring a purely rational Humanism or Idealism … not from actual experience across the ages. Greek government by the demos at one point served the Greeks well ... and then proceeded to dishonor that record – especially in the leading Greek city-state of Athens – by engaging in very stupid politics, "democratic" politics that ultimately brought Athens down from its power and greatness. The Athenian demos, as it turned out, was easily led by unscrupulous politicians, who manipulated the masses into making horrible political decisions ... such as ordering the death of Athens' premier philosopher Socrates, because he annoyed these unscrupulous politicians with his constant criticism of their behavior. That same stupidity was found also in the decision of the Athenian demos to turn a deaf ear to their fellow Greeks who complained that the money being sent to Athens, as Greece's leading city-state, to equip a Greek army designed to protect Greece from the Persians, was being used instead to dress up Athens with fancy new buildings and other public works. The other Greek city-states would have been happy to have kept this money, if it was not going to the intended purpose of Greek defense, to undertake the same architectural upgrade to their own communities. Ultimately, Athens' selfishness led to a horrible series of Peloponnesian Wars among Greece's various city-states, (431-378 BC), wars that finally destroyed not only Athens politically, but much of the rest of Greece as well. Consequently "democracy" was not well remembered in the West. As we have already noted, the philosopher Aristotle himself (who was widely read by educated Westerners ... up until recently), made it clear that it is not the form of government – whether government by one, a few, or the many – that produces better government ... but instead the moral intentions of those who do govern. Dictators are not the only problem affecting mankind. Democracies (Hitler’s Germany was actually a "democracy") can be horrible, if horribly led. Thus it is that the men (who had read their Aristotle!) who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 to put together a new American Constitution in order to perfect the Union of their thirteen states were definitely not intending to create a democracy. They instituted instead a "republic" built on a regime of foundational law … which itself called for a "mixed" system, one of political checks and balances. The Republic's Constitution was carefully designed to permit, yet restrict, popular participation in the nation’s politics – out of a fear of democratic instincts getting out of control. Their new Federal Union would include government by one (the President), the aristocratic few (the Senate) and the democratic many (the House of Representatives) ... understanding that this system would work only when all three forms of rule worked together. This was to prevent any one of the three forms of government to take over the other two and establish a monopoly on power ... which unchecked always leads to great social evil. It would be until only the beginning of the 20th century – notably with the arrival on the scene of the highly Idealistic American President Woodrow Wilson, who saw "democracy" as the cure-all for the world’s ills – that "democracy" would come to have the glamor and intense devotion that it does today. Thus it is only recently that Western political philosophers have rejected the wisdom of the ancients and moved to the call for pure "democracy" both at home and abroad. This is so much so the case that it is now almost religious heresy to voice any hesitations about bringing (especially imposing) democracy as some kind of wonderful benefit to the world's societies … without having also laid the accompanying moral groundwork that democracy would need in order not to lead to horrible social chaos and even cruel tyranny. Democracy is not a basic human right. It is a major social responsibility. 1Actually, only twelve of these new states sent representatives to Philadelphia that summer … because tiny Rhode Island was afraid to join the new Union, fearing it would lose all sovereignty to a new governing authority. Rhode Island would, however, soon join … when it was clear that the new Constitution protected the states' authority – rather than removed it. |

|

|

The Mycenaeans or Achaeans

At

some very distant point in time, dating anywhere between 1900 BC and

1500 BC, a number of different Aryan speaking peoples moved westward

from southwestern Russia and invaded/settled in wave after wave into

the land we know as Greece. These

invaders, sometimes identified as "Mycenaeans" or sometimes as

"Achaeans," spoke an early form of Greek and would become known to

later Greeks as the military heroes in Homer's epic war story or poem,

the Iliad. There on that southernmost Peloponnese Peninsula they

established fortified towns in the valleys between the many mountainous

ridges that reach down to the sea and divide Greece into a number of

distinct geographic units. Each town was headed by a

chieftain or warlord (or "king" as we later termed them). Eventually a number of important Greek cities, such as Athens and Thebes that developed later, could easily trace their origins back to Mycenaean times. |

Mycenae at a distance

Miles Hodges

Mycenae

Miles Hodges

The approach to Mycenae and

the Lions Gate

Miles Hodges

Details of the Lions Gate

Miles Hodges

A view of entrance from inside

the walls

Miles Hodges

House foundations inside

Mycenae's walls

Miles Hodges

The Royal Tombs

Miles Hodges

The Citadel at Mycenae

Miles Hodges

The Citadel at Mycenae

The Citadel at Mycenae

Miles Hodges

View of the surrounding countryside

from the Citadel at Mycenae

Miles Hodges

A princely death mask of

gold ("Mask of Agamemnon")

from the Upper Grave Circle at Mycenae - 1500s

Mycenae – Lion head of thick

plate gold

From the upper grave circle

Athens - National Archeological

Museum

Gold cup from the Upper Grave

Circle at Mycenae, 1500s BC

Gold pendant of a goddess – from the women's grave in the Upper Grave Circle,

Mycenae, 1500s BC

Other Mycenaean era sites and archeological findings

Tiryns

Tiryns – a general view

Entryway through Tiryns' thick walls

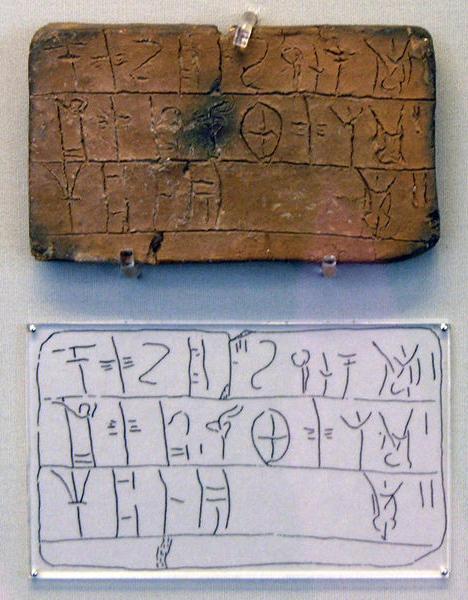

Mycenaean tablet inscripted

in linear B coming from the House of the Oil Merchant

The tablet registers an

amount of wool which is to be dyed

National Archeological Museum,

Athens

Achaean armor made from boars'

tusks and bronze – 1400s BC

Achaean warrior in boar's-tusk

helmet. Ivory – from a chamber tomb at Mycenae, 1300s BC

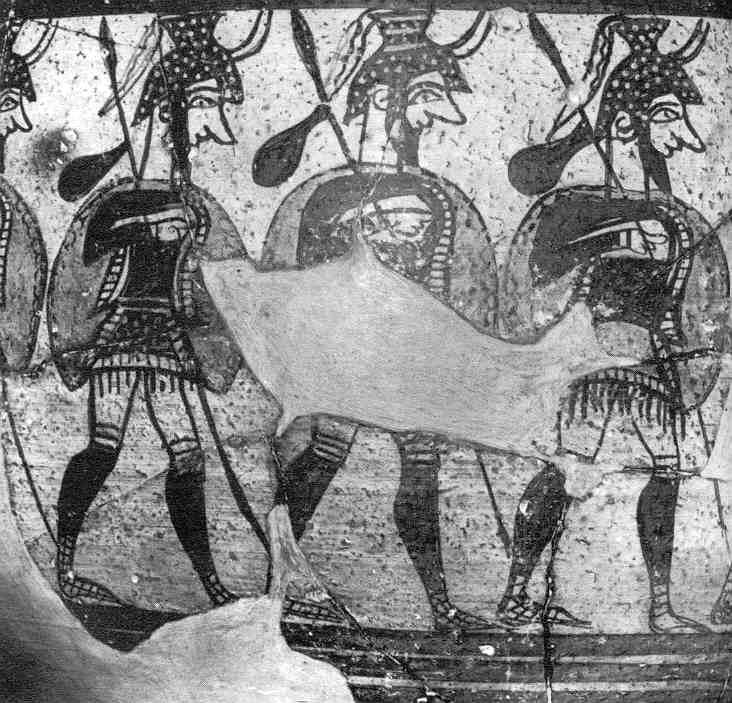

Soldiers marching against

the (Dorian?) barbarians

– from the "Warrior Vase" at Mycenae, 1100s BC

Athens - National Archeological

Museum

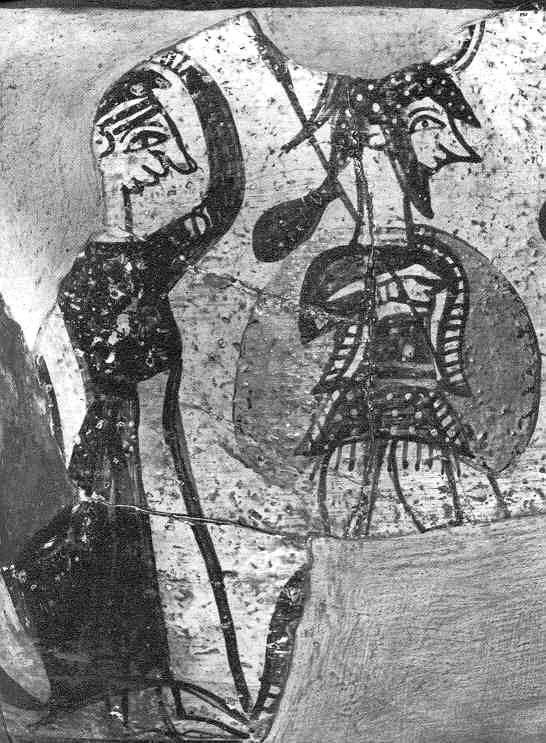

A woman laments the departure

of the soldiers –

from the "Warrior Vase" at Mycenae, 1100s BC

Athens - National Archeological

Museum

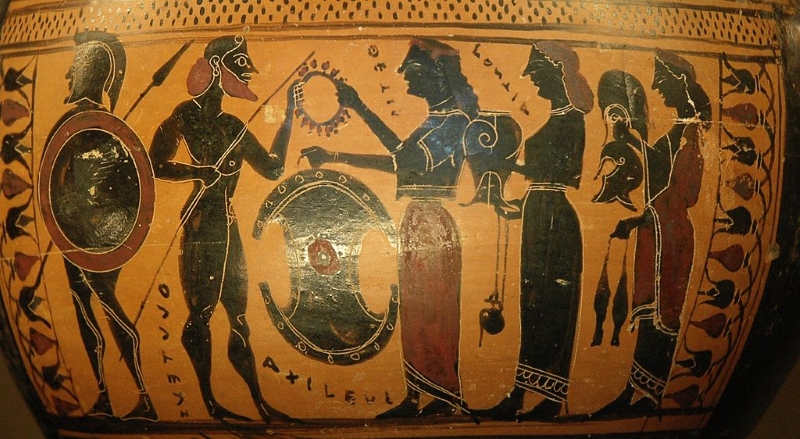

Thetis gives her son Achilles weapons forged by Hephaestus

Paris, Louvre Museum

Achilles treating Patroclus wounded by an arrow

Berlin, Altes Museum

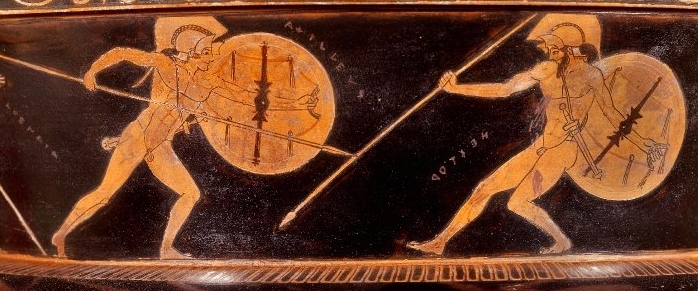

Hector fighting Achilles

British Museum

The earliest-known depiction of the Trojan Horse – from the Mykonos vase (c. 670 BC)

Archeological Museum of Mykonos

|

The Dorians ... and a Greek "Dark Age" But this Mycenaean/Achaean strength eventually began to decline, and after approximately 1150 BC Greek culture fell into a 400 year-long Dark Age. This was either caused by, or led to, yet another wave of Greek invaders from the Northeast, the "Dorians." All archeological evidence seems to indicate that probably (though not certainly: debate lingers on) the Dorians disrupted life in Greece in a very major way. Certainly the Doric invasion set off a reactive wave of Greek migrations in around 1000 BC – principally to the shores of western Asia Minor. Ionians from Attica (around Athens) retreated across the Aegean to the central western shores of Asia Minor (to Miletus) and gave their name "Ionia" to this particular region along the Asia Minor coastline. Aeolians (perhaps a later group of Greeks to appear on the scene) settled the north western shores of Asia Minor. Dorians themselves eventually continued their own migration across the Aegean to the shores of southwestern Asia Minor and then onward to Crete. In

any case, the warlike Dorians eventually settled themselves into the

Peloponnesian peninsula – where they ruled over the helots, the

enslaved or enserfed Greeks who had originally lived in the area.

Eventually Sparta grew up as the leading city-state at the heart of

Doric culture – famous for the intense military discipline all its

citizens (women as well as men) were put under. But

interestingly, Athens (and its hinterland of Attica) managed to fend

off the Dorians – and retain its older Achaean culture. Greece's "Archaic Period" (700s – to the late 500s BC)

In the 700s BC Greece began to experience a commercial revival, growth of its population – and emergence of political powers in reviving Greek towns in the form of local aristocracies (rule by the heads of prominent families). But prosperity also strengthened the power of the more numerous commoner class, who found champions in the form of tyrants – who would use their political power to support the political cause of the Greek lower classes. Political revolutions of sorts thus shook the Greek world as new prosperity put power in the hands of all sorts of people. As a result democracy (rule by the common people or demos) – or something like it – resulted in a number of cities. This

rise of the common classes however inspired a strong political reaction

in Sparta, where a small elite of Spartan military citizens, who ruled

over the vast numbers of subject peoples in surrounding towns and

villages, took an ever-tougher stance of rulers over ruled – creating

Sparta's famed military aristocracy. More Greek colonization around the Mediterranean

With this economic revival of Greece there was also a large increase in the population – causing a serious strain on Greece's available farmland to feed that population. However, the surrounding seas, which the Greeks viewed not as a barrier but as a source of life (in fact a superhighway for them to move across), offered them an escape from their problems. Thus, excess population was sent out to create new settlements or colonies – extensions of sorts of the sending cities. A new wave of Greek migration thus developed. During

the 700s and 600s BC Greeks sailed east and west and discovered lands

that they could colonize with their excess population (much as other

cultures were doing at the time, notably the Phoenicians – located

along the Syrian coast – with whom the Greeks had active commercial

relations). From the city of Corinth colonies were established to the West on the island of Sicily and on the southern Italian peninsula (this would eventually come to be called Magna Graecia or "Greater Greece"). One of those colonies, Syracuse (founded in 733 BC), soon became a major city by its own right. Some of the Euboean towns (just north of Attica) sent settlers to the Syrian coast. From Miletus and other coastal towns in Asia Minor (a region known as Ionia) settlers were sent through the Dardanelles straits into the Black Sea where they then established numerous Greek towns around the coast. Settlers also headed south to the Egyptian and Libyan coasts of Africa. Others sailed west beyond Sicily and established towns along the coast of what is modern day France (notably at Marseille). By the 500s BC they were reaching to Spain and northern Italy. Thus in the course of the 600s BC "Greece" came to describe an area much larger than the land we today call Greece. In those ancient days "Greece" encompassed a whole huge area along the northern half of the Eastern and central Mediterranean Sea. And if we include the various Greek cities planted along the coast of the Western Mediterranean (such as Marseilles in southern France) we are describing a culture that was very extensive. Soon Greek towns along the Western coast of Ionia (Western Turkey) and Magna Graecia (Sicily and Southern Italy) would achieve tremendous cultural growth of their own – often surpassing in quality the level of culture of the sending cities back home. |

Greek colonization around

the Mediterranean

Wikipedia - "Ancient

Greece"

|

|

|

|

Greek democracy The Greeks were also a people given to much thought about the best way to shape, run, and occasionally reform Greek society. All Greeks originated as proud tribal peoples, complete with their tribal assemblies that all men were expected to attend ... for their services would be frequently called on and it was best that they personally had "bought into' the social decision, especially on the matter of war, in order to assure their commitment to the cause. And out of this experience grew the idea of the people governing themselves. Each tribe, even when it grew in number and became "civilized" (meaning the people now lived in cities with temples, commercial buildings, apartments, town walls, etc.), saw itself as practicing "democracy" – government (kratos) by the citizens (demos) of the towns or cities themselves. However

the definition of demos or citizen was not as broad as it is today.

The category "citizen" by no means included all inhabitants of the

city-states but only those males of a recognized tribal pedigree ...

meaning full members by birth of one or another of the old tribes

originally making up the community. Foreigners or xenoi living in the

cities – which often included a huge number of the industrial or

commercial workers (and certainly also the many slaves) – were actually

quite numerous in Greek culture. These individuals did not qualify for

democratic privileges ... even if they were descendants of several

generations of xenoi living and working in these "democratic"

city-states. During most of Greece's Archaic Period the Spartans had been considered the dominant political power or hegemon in Greece. But during the 500s BC Athens, which was well positioned at the center of this huge Greek world, and possessing a number of natural advantages (a very strong citadel, a wide fertile region surrounding it, and closeness to the sea), soon rose to its own prominence. Also, having the strongest navy of all the Greek city states (thanks to its political leader Thucydides), Athens was early looked to in order to provide leadership in organizing the city states into a great Greek navy, one designed to keep the Persians away from Greek shores. But the Athenians proved themselves as well on land as foot soldiers. Thus

Greek leadership was divided between — and often competed for — by both

Sparta and Athens (Corinth and Thebes were also powerful, though only

at a secondary level). Athens' struggle to secure democracy But Athens was wracked by internal problems. Athens' rich and powerful aristocracy, long used to dominating Athens' political and economic life from its political council, the Areopagus, found itself increasingly challenged by the Athenian commoners (not really all that common, since they still occupied a much higher status than the more numerous xenoi ("foreigners") in Athens and the even more numerous slave portion of the Athenian population). The

aristocrats first attempted to control Athens' affairs with a very

tough legal code or constitution (in which the penalty for a wide range

of offenses was death) laid down by Draco (ca. 620 BC) – and thus very

"Draconian" – which, though an improvement over the older oral laws and

traditions, still did not satisfy the political desires of the

commoners. However his constitution did provide for the creation of a

Council of Four Hundred, its members drawn from the commoners by lot.

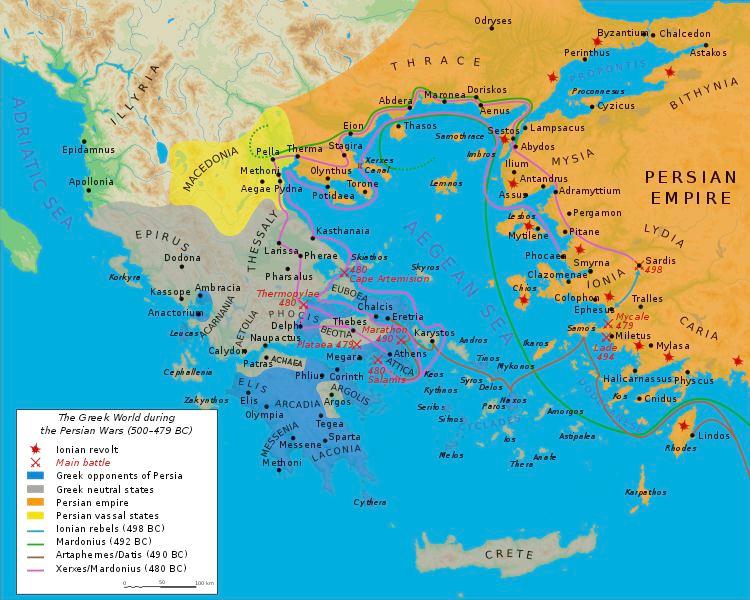

The challenge of the Persian Wars In the latter part of the 500s BC, just as a number of Greek towns were beginning to grow in power as "city-states," the Persians surprised the world by conquering Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt … and Greek Ionia. Thus was the mighty Persian Empire born. This was the first time ever that nearly the whole of the Near East had been brought under a single rule. Some of the Greeks living in Ionia did not particularly take well to this Persian domination (though others did, even serving in the Persian military) and rose up in revolt against Persian rule in the 490s BC. The citizens of Athens were quick to back the Ionian rebels – who, however, were eventually forced back under Persian rule. This action of Athens and other Greek city-states in supporting the Greek Ionian rebellion drew the wrath of Persia … and led to a Persian desire to crush any further Athenian or other Greek "meddling" in Persian affairs. Thus the Persian Greek wars began. This Persian response to Greek "meddling" in turn forced the two leading Greek city-states, Sparta and Athens, into cooperation (in fact forcing a general Greek unity among all the Greek cities that had previously been lacking). The Battle of Marathon (490 BC). Quite surprisingly (to the Persians, anyway!), in a number of major encounters, the Greeks succeeded in defeating the Persian armies and navy sent to Greece, thus not only helping to secure Greek freedom, but elevating Greece – and in particular Athens – to a new status politically. The

Persian king Xerxes, who took over when his father died in 486 BC, was

as dedicated to the reduction of Greece, and the total destruction of

Athens. After having crushed the Egyptian revolt, and after

three-years of military preparation, Xerxes was finally ready to

undertake just such a mission. However, Sparta now joined Athens

in the effort to fend off the Persians. But most of the other

Greek city-states still chose to stay out of the action. At

the same time the Athenian-led Greek fleet managed to fight off the

Persian fleet at Artemisium, until news of the Greek defeat broke the

Greek spirit and the Greek fleet withdrew to Salamis. The

Persians then continued their advance through Greece, destroying

city-state after city-state as they went, including the city of Athens

as well. The

next year, Xerxes was ready to try again to conquer Greece, and sent

his troops to Greece, where they assembled at Plataea. A battle

which then took place there did not go well for the Persians, who lost

their commanding general and then found their camp surrounded, and

ultimately destroyed by the Greek hoplites. At the same time,

another sea battle – at Mycale – did not go well for the Persian fleet,

making the Persian defeat even more obvious. Yet

for the Greeks it proved to be a major turning point in the history not

only of Greece but even of Western civilization itself. From this

point on, Greece, led most importantly by Athens, would leave a deep

political, social, intellectual and moral impact on Western

civilization … one that would shape that civilization not only in the

many centuries of Greek political and cultural greatness, but even down

to today, where that same legacy is built deeply into the ways of the

West. |

|

The Golden Age of "Periclean

Athens" (and Greece)

The Delian League. By the mid-400s BC Athens was the dominant sea power in Greece, Sparta the dominant land power. But the sea was the more important element in Greek life at that time – and thus Athens naturally tended to dominate Greek affairs. In fact, although the Persians had been twice defeated by the Greeks, their shadow continued to loom over Greek thinking – and thus Greek defenses stood always at the ready, headed up primarily by Athens which had organized a number of Greek cities into a defense organization known as the Delian League.  "Periclean Athens." The fact that the Greeks had escaped Persian rule was to become important in the future development of

Greece. Spurred on by the continuing threat of Persia, Greece

developed its own strength, especially under the leadership (even

dominance) of Athens. Athens, after the two grand defeats of the

Persians at Salamis and Plataea, soon became the center of a newly

rising Greek civilization, with Athens itself reaching the height of

its power and glory about 450 BC, roughly the time of the political

leader Pericles (490-429 BC). "Periclean Athens." The fact that the Greeks had escaped Persian rule was to become important in the future development of

Greece. Spurred on by the continuing threat of Persia, Greece

developed its own strength, especially under the leadership (even

dominance) of Athens. Athens, after the two grand defeats of the

Persians at Salamis and Plataea, soon became the center of a newly

rising Greek civilization, with Athens itself reaching the height of

its power and glory about 450 BC, roughly the time of the political

leader Pericles (490-429 BC). Pericles was born to a highly-placed noble Athenian family … and followed in his father's footsteps to command the Athenian military in some of its most important engagements – most notably those conducted during the First Peloponnesian Wars of Athens versus Sparta in the period 460-445 BC. Pericles was also a very close friend of the philosopher Anaxagoras. And Pericles became very active in the world of politics, becoming the primary prosecutor against the politician Cimon, who had succeeded in having the great general Themistocles (a warrior that Pericles greatly admired) expelled or "ostracized" from Athens. Pericles eventually was indeed able to have Cimon himself ostracized. Pericles was a practitioner of "democratic" politics … doing what he could to use state resources to support the poor – winning obvious favor from that huge sector of the population. Indeed, he identified himself as a champion of the little people (tyrant). And he also limited voting rights to only those Athenians with both parents being Athenian citizens … so as to keep the voting privileges enjoyed by even the poorest Athenians from being diluted by the massive entrance of the foreigners or xenoi into the ranks of Athenian citizenship. This all seemed to support the idea that indeed, Athens was a very grand city … everyone (at least its citizens) able to afford the pleasures of a highly successful society. Athens' great cultural achievements. And yes, indeed, the mid-400s marks the grand age of Athens. Athens' democracy and the leadership of the very capable general/statesman Pericles combined to offer Athens' citizens a very rich life. A lavish building program turned the city into an architectural marvel. And the tendency of Greece's finest minds to gravitate to Athens made it "the school of Greece." |

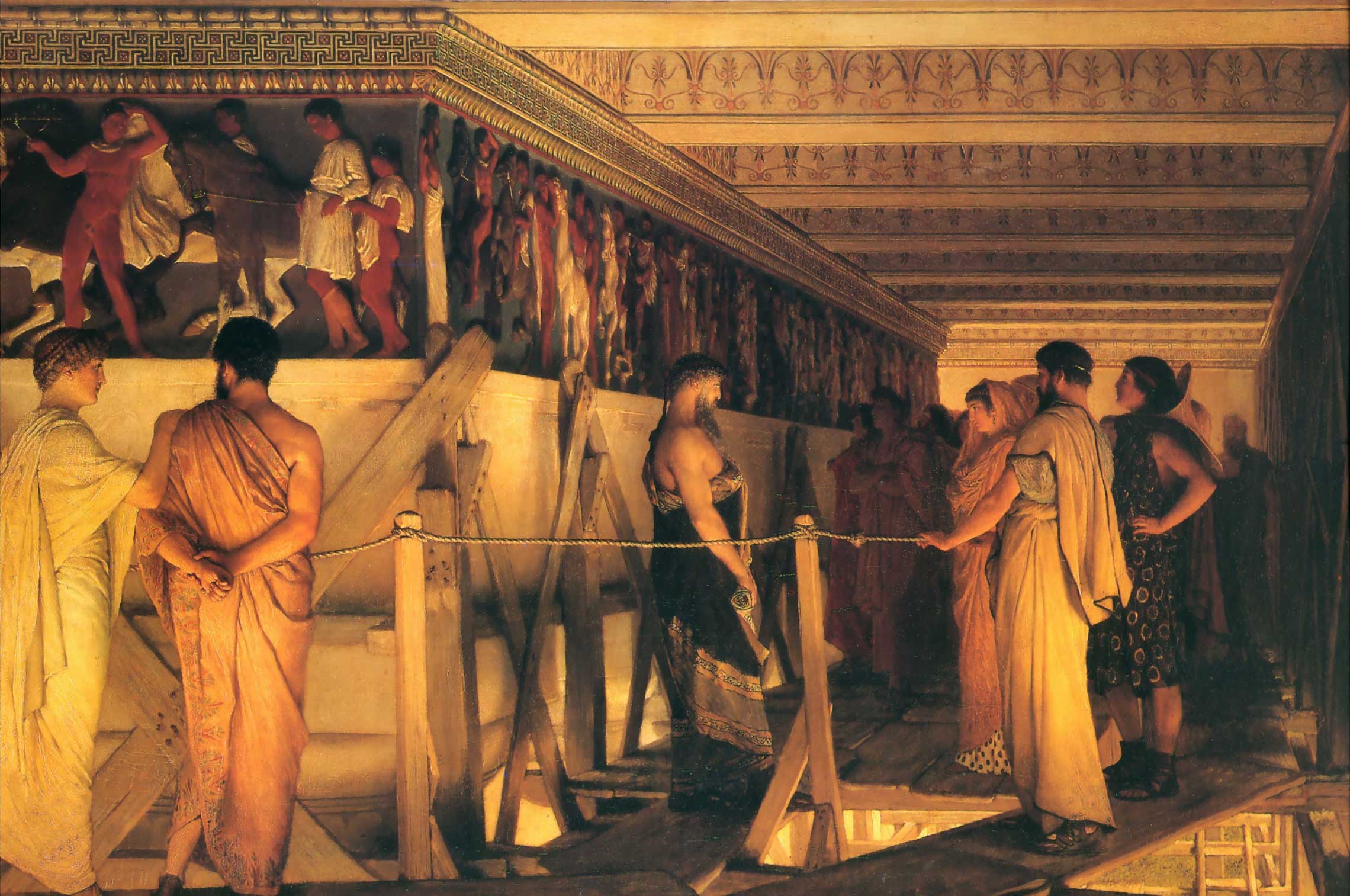

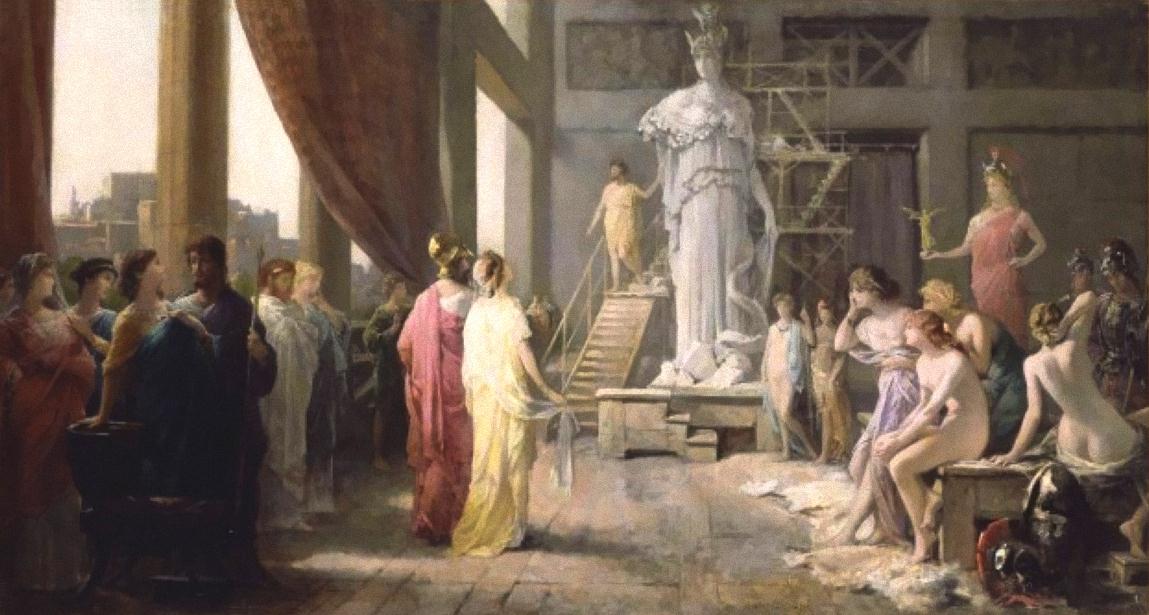

Phidias showing the freize of the Parthenon to his friends - by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1868) Pericles and Aspasia in Phidias' studio admiring his statue of Athena - by Hector Leroux

Birmingham (England) Museun and Art Gallery

Athens - with the Acropolis

in the distance

Miles Hodges

The front of the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The front of the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The entrance to the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Athena-Nike Temple on

the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Propylaea Temple on the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Erectheum Temple on the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Erectheum Temple on the

Acropolis

Miles Hodges

A view of the Parthenon on

the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Parthenon Temple atop

the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Dionysian Theater – viewed

from the Acropolis

Miles Hodges

The Theater of Herod Atticus – viewed from the Acropolis

Miles

Hodges

Other Greek communities

Sparta

Foundation walls of

Sparta

Miles Hodges

Foundation walls of

Sparta

Miles

Hodges

Olympia

Ruins of ancient

Olympia

Miles Hodges

Ruins of ancient

Olympia

Miles Hodges

Ruins of ancient

Olympia

Miles Hodges

Reconstructed stadium at

Olympia

Miles

Hodges

|

|

Athenian democracy under challenge Actually,

Athenian democracy was more an attitude than a political institution or

policy. The commoners were jealous of their political rights and

quick to defend them against any appearance of usurpation from any

source. Tragically, this "democratic" attitude was easily molded

by the shapers of "popular opinion" – by the political satire of the

popular theaters of Athens ... and by the political maneuvering of

clever speakers in the Athenian Assembly, in particular by the Sophists

and their wealthy disciples – sort of the ancient version of modern day

trial lawyers, who specialized in playing on the prejudices and fears

of the people in order to whip up this or that popular mood ... which

they skillfully directed according to their own personal ambitions. The Sophists. As the Athenians' public life in the middle and second half of the 400s BC developed in its richness and importance, wealthy families hired tutors for their sons in order to prepare them for leadership roles in the public assemblies. This was where the laws guiding Athens would be shaped. This was where economic, diplomatic and military decisions that were key to the well-being of the community would be made. They wanted their sons to become persuasive in their rhetoric, quick in public debate and noble in their public bearing – so that they would find themselves at the heart of the doings of these public assemblies. A particular class of wise ones or "Sophists" (Greek sophia = "wisdom") gladly offered their teaching services for a fee to these families. They built their learning or wisdom around the need to produce practical results in the form of skilled or adept students. These Sophists were sort of the ancient version of modern-day trial lawyers, who specialized in using very clever and highly persuasive "rational" arguments in order to win their cases. As demagogues, they proved highly skillful in cultivating the prejudices and fears of the people … to whip up this or that popular mood. As for the higher issues of life such as truth, goodness, justice, etc., in general the Sophists tended to be agnostic – that is, they professed to have no knowledge about (or even concern for) such ultimate or transcendent things. Indeed, they functioned as if such things did not really matter in the course of actual existence. Success was measured not in possessing the knowledge of ultimate truth, but in knowing how to use truths (or "truthiness" as it is sometimes termed today) for personal political and economic gain.

Democratic cruelty

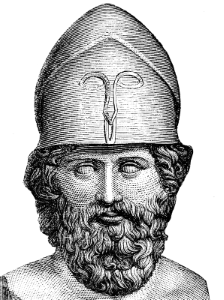

Ostracism. At the same time that wealthy Athenian families were very busy in creating something of a newly-rising ruling class of "more enlightened" individuals, at the level of the lower social orders tendencies were also developing that would serve to weaken further the moral foundations of Greek democracy. One of these tendencies was the long-standing practice of "ostracism" or the exiling of Athenians by their fellow citizens, because for one reason or another they had fallen out of popular favor. At a special general assembly, citizens were invited (usually by these Sophist-trained demagogues) to record the name of a person they might want exiled on a broken piece of pottery and deposit it in urns. These pottery shards or ostraka were then tallied by a public official. The person receiving the most votes (although at least a minimum of 6,000 votes) was "ostracized" and thus automatically exiled for ten years.  Themistocles is ostracized. In 472 or 472 BC the Athenian general Themistocles … who had been one

of the Athenian commanders at the Battle of Marathon, who then led the

Athenians to develop massive sea power and subsequently devised the

scheme to trap and destroy the Persian navy at Salamis, and who was the

leading political figure over the next ten years … was brought before

the ever-suspicious Athenian Assembly – fed by rumors coming from the

Spartans of a role in a political conspiracy (entirely false in fact,

designed cleverly by the Spartans to destroy their rival Themistocles)

– and adjudged by the Athenian commoners to be guilty of the crime of

arrogance. He was thus was ostracized. He fled to Macedonia

– then moved on to Ionia … where the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes offered

to bring him into Persian service as a regional governor! Themistocles is ostracized. In 472 or 472 BC the Athenian general Themistocles … who had been one

of the Athenian commanders at the Battle of Marathon, who then led the

Athenians to develop massive sea power and subsequently devised the

scheme to trap and destroy the Persian navy at Salamis, and who was the

leading political figure over the next ten years … was brought before

the ever-suspicious Athenian Assembly – fed by rumors coming from the

Spartans of a role in a political conspiracy (entirely false in fact,

designed cleverly by the Spartans to destroy their rival Themistocles)

– and adjudged by the Athenian commoners to be guilty of the crime of

arrogance. He was thus was ostracized. He fled to Macedonia

– then moved on to Ionia … where the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes offered

to bring him into Persian service as a regional governor!Tragically for Athens itself, it would take some time and distance from this sad episode before the Athenians would recognize the cruelty that they had delivered to the one man … who not only saved Athens from Persian destruction, but put the Greeks on the path to greatness. Athenian arrogance / Athenian imperialism

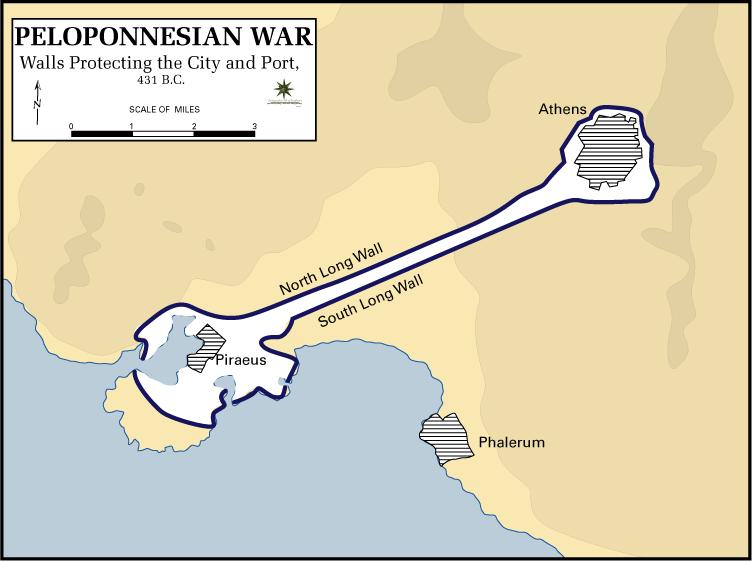

Another (and similar) major problem facing the Athenian democracy would be the arrogant attitude it came to assume with respect to its fellow Greek city states – and the resentment this would breed among these other Greeks. At this point Athens no longer was led by wise men with a deep sense of high-minded virtue, but by cynical, manipulative, self-serving politicians, setting a similar moral tone for the entire Athenian community. With the passing of time, as the Persian threat seemed to dwindle – but Athenian collection of dues from its allies for "defense" purposes continued nonetheless – resentment by members of the Delian League against Athens grew, especially when it became obvious that this money the other cities were sending to Athens had little to do with Greek defenses and more to do with a lavish Athenian building program going on during Athens' "glory days." Consequently, Athens' Greek allies in the Delian League felt as if they had been seduced into surrendering their independence to a growing Athenian Empire. Certainly also, the money they were sending Athens could have been used to improve their own cities. Anger against Athens began to grow among the other Greek city-states. Sparta, the major rival to Athenian power, with its well-disciplined land army, was quick to take advantage of this discontent and organized a rebellion against Athens in 431 BC. Also Thebes, seeing the growing mood of Greek rebellion against Athens, decided to make a bid for dominance in Greek affairs. The Peloponnesian Wars, and the decline of Athens. Thus wars (the "Peloponnesian Wars") broke out in Greece (431-421 BC; 421-404 BC; 395-378 BC), wars that tended to ravage Greece – yet seemed to resolve nothing. The worst of these were the engagements between 431 and 404 BC. Truces would be declared only to have one party or another decide that it was advantageous to break those treaties and start up a new round of wars. Also political leaders played treacherous games of shifting their loyalties according to their personal advantage. Pericles' efforts to keep Athenian spirits high. For a while the great general and Athenian political leader Pericles was able to keep Athenian spirits high as it struggled with the hostility of the surrounding Greek world. But Athens had taken on a war that would drain it economically and spiritually … and offer no gain whatsoever in return. Consequently, Athens found itself bleeding to death economically and spiritually.  Decline.

Thus things went quickly downhill for Athens. A long-lasting

siege of Athens by Sparta created devastating conditions within Athens,

taking the lives of many Athenians, including Pericles (429 BC).

Athens' new leader Alcibiades

(Pericles' nephew) proved to be largely a disaster for Athens, as he

led Athens on ruinous expeditions and switched loyalties constantly ...

including even siding with Athens' enemies, first Sparta (415-412 BC)

and then Persia (412-411 BC) during his cynical political career! Decline.

Thus things went quickly downhill for Athens. A long-lasting

siege of Athens by Sparta created devastating conditions within Athens,

taking the lives of many Athenians, including Pericles (429 BC).

Athens' new leader Alcibiades

(Pericles' nephew) proved to be largely a disaster for Athens, as he

led Athens on ruinous expeditions and switched loyalties constantly ...

including even siding with Athens' enemies, first Sparta (415-412 BC)

and then Persia (412-411 BC) during his cynical political career!Ruin. The war gradually led not only Athens but also much of the rest of Greece to ruin. Finally, in 405 BC, the Spartans (now allied with the Persians) defeated Athens even at sea – and Athens was forced into a humiliating surrender, forced to tear down her town walls, surrender her fleet and give up all her overseas possessions. Only Sparta's compassion prevented Corinth and Thebes from getting their wish to level all of Athens and also enslave the entire Athenian population. Socrates is condemned to death. Even more tragically, the West's most famous philosopher, Socrates – who was loudly critical of the amoral antics of the Sophists – would eventually (late 400s BC) become the object of the satire of the playwrights (notably Aristophanes) and the demagoguery of the Assembly speakers. Both groups turned the public against him. In 399 BC the Assembly voted for Socrates' death ... given somewhat honorably in that he was to inflict this punishment on himself (poison, usually). Actually, they expected Socrates to do what most Athenians did when the Assembly turned against them: flee Athens. This was certainly the counsel of Socrates's devoted disciples. But Socrates reasoned that to flee would be to discredit the very truths and moral principles to which he had dedicated his life in his teachings. Thus he took the poisonous hemlock and died, surrounded by his disciples. Socrates's death by the decision of Athens' democratic Assembly consequently caused democracy to be intensely distrusted by some (Socrates' famous student Plato, for instance) or at least not highly regarded (Plato's equally famous student Aristotle, for instance). |

|

Socrates

is known largely through Plato's heroized representation of him.

We know that subjects such as social ethics or public morality were of

great interest to him – though he was also interested in such subjects

as justice, beauty, goodness, and even physics and metaphysics.

Above all, he was interested in conveying to his students the

understanding of how to live a life of honor and truth … particularly

in service to the larger social order. Socrates

is known largely through Plato's heroized representation of him.

We know that subjects such as social ethics or public morality were of

great interest to him – though he was also interested in such subjects

as justice, beauty, goodness, and even physics and metaphysics.

Above all, he was interested in conveying to his students the

understanding of how to live a life of honor and truth … particularly

in service to the larger social order.He was keenly aware that objective reality and what our minds understand of reality are separated by a great mental divide (the general consensus of Greek philosophy by that time). But to the optimistic Socrates, rational inquiry, meticulously but humbly pursued (his dialectical method), could close this divide. In using rational methods of inquiry, human mind and soul could be brought to discover transcendent (thus absolute) truth and goodness – and personal happiness. Socrates felt optimistically that knowing the truly good would necessarily direct a person to act in line with this knowledge. Also, the quest for such knowledge was the very heart of life itself – its highest form (almost a divine enterprise). Unfortunately, the Athenians proved not to be so enlightened by the truth as he had hoped, and ordered him to poison himself … for "teaching the youth not to reverence the gods" (something actually not the case at all). |

|

Socrates's student Plato (427-347 BC)

The realm of the Ideon. These perfections were idealized Forms or Ideas (Ideon or Eidei – terms he used interchangeably) like geometric forms that describe life ideally. But though these Forms existed only as ideas, they were more real than the visible world around us. But how could Plato be so sure that these Forms we had never ever seen were so real? His thinking went something like this. We know, for instance, that there are no perfect circles to be found anywhere in nature. Some things in nature only tend toward a perfect circular form and thus may be called circular. But how is it that we know that they are not perfectly circular? Only because for some strange reason our minds can indeed hold clearly a distinct understanding of a perfect circle – though we have never seen such anywhere in the world around us. We can thus make such assertions about circularity – not because we have seen perfect circles, but because we certainly hold the idea of a circle clearly in our mind. If we could not conceive of such perfect ideas in our minds, then we would not be able to think clearly or rationally. The fact that we can think about circles, to Plato proved their existence. This existence, of course, was not in the immediate world around us, but in some mysterious realm of higher being or thinking. Plato was interested in uncovering this perfect world of the Ideon or Forms – in bringing it to light to human understanding. Indeed, this was to Plato (and by many "Platonists" who came after him) a religious enterprise – not just a matter of detached scholarship. Plato and the realm of politics. With regard to the world of politics, most understandably, after what the Athenian Assembly did to his teacher Socrates, Plato was no lover of democracy. But Plato did believe that there existed part of the realm of the Ideon ... able to guide our shaping of an ideal state. In his Republic, Plato described that ideal state as one that was divided by classes or castes into three levels of society: workers, guardians (soldiers) and governors ("philosopher kings"). Tragically, when later in life Plato was called to Syracuse (Greek Sicily) by Dion (a former student of Plato's) to help Dion's young but dissolute nephew Dionysius II become just that "philosopher king" and put such an Ideal State into effect, the whole thing ended up most disastrously. Dionysius's older brother-in-law Dionysius the Elder, who was actually ruling Syracuse at the time, was deeply irritated by Plato's disdain of his attempts at being a popular tyrant … and had Plato arrested. Plato was spared death only by being sold into slavery … from which a friend of Plato's went on to purchase his freedom. Oddly enough, when Dionysius the Elder died, Plato was invited back by Dion to Syracuse to try again with the young Dionysius. But Dionysius fought with his uncle Dion, and had him expelled … but forced Plato to stay on. Plato was finally able to get out of Syracuse. Ultimately the "philosopher king" Dionysius found himself facing a popular uprising … in which he was ultimately driven from power. What Plato actually learned from all this very non-Idealist experience in the realm of politics is not known to us today. Nothing in Plato's writings points to any kind of development of his political thinking because of this sad experience. Apology |

Raphael's School of Athens

At the center, Plato pointing upward to the heavens; Aristotle pointing downwards to the earth ...

a keen depiction of the essential philosophical difference distinguishing the two!

Aristotle went in a direction opposite that of his teacher,

Plato. While Plato focused his attention on the mysterious world

of the perfect Forms, Aristotle focused his attention on the messier

visible world immediately around him. Aristotle was greatly fascinated

by this empirical or physical world. He was looking for Plato's

Forms actually contained within this visible world.

But Aristotle eventually surmised that these Forms were merely

abstractions in our mind which we use to categorize the immense

information that comes to us about the surrounding world. These Forms,

though useful to human logic, were themselves only mental constructs or

kategoriai (categories)

… useful to the human mind in developing an organized understanding of

how to understand and work with the surrounding world. "Dog," or

"barn", or "hot", or the color "red" were just such categories.

They had no separate existence like gods or defining spirits (as Plato

had asserted).

But Aristotle was deeply interested in exploring this world of

categories, trying to discover as many different categories as possible

… in all fields of life, from biology to geology, but also in the realm

of logic, ethics, and politics.

As already mentioned, in the field of politics, he was not particularly

interested in one or another particular category of social

organization, whether a society governed by a single person, or a few,

or even the many. What he understood as the "good society" was

one which – whatever the specific form – was carefully ordered by a set

of very strong moral foundations … ones that human cleverness would not

be able to manipulate – but which would offer clear guidance to that

society as it took on life's various challenges. He made this

very clear in his famous publication, Politics.

Most interestingly however, when it came to discussion of things beyond

this earthly realm – the heavenly realm of the sun, moon and stars –

Aristotle evidenced a religious awe. Though the earth might be marked

with physical imperfections, these heavenly bodies were the essence of

the divine, for they were perfect – perfect in their circular shape and

circular movement. Thus for Aristotle the perfect-imperfect

dualism in life occurred not between things seen and unseen (as it had

for Plato), but between the imperfect things seen on earth and the

perfect things seen in the heavens.

Thus even in his religion, Aristotle remained focused on the visible

universe around him. "Heaven" was not a place found beyond the

visible world … but instead was located quite visibly in the skies

above. Beyond that, Aristotle had no particular opinion about the

"heavenly realm" of the gods or whatever.

Go on to the next section: Alexander and Hellenism

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges