|

|

CHAPTER X IN AFRIKANDER BONDS

Pretoria: December 3rd, 1899.

It was, as nearly as I can remember, midday when the train-load of prisoners reached Pretoria. We pulled up in a sort of siding with an earth platform on the right side which opened into the streets of the town. The day was fine, and the sun shone brightly. There was a considerable crowd of people to receive us; ugly women with bright parasols, loafers and ragamuffins, fat burghers too heavy to ride at the front, and a long line of untidy, white-helmeted policemen—'zarps' as they were called—who looked like broken-down constabulary. Someone opened—unlocked, that is, the point—the door of the railway carriage and told us to come out; and out we came—a very ragged and tattered group of officers—and waited under the sun blaze and the gloating of many eyes. About a dozen cameras were clicking busily, establishing an imperishable record of our shame. Then they loosed the men and bade them form in rank. The soldiers came out of the dark vans, in which they had been confined, with some eagerness, and began at once to chirp and joke, which seemed to me most ill-timed good humour. We waited altogether for about twenty minutes. Now for the first time since my capture I hated the enemy. The simple, valiant burghers at the front, fighting bravely as they had been told 'for their farms,' claimed respect, if not sympathy. But here in Pretoria all was petty and contemptible. Slimy, sleek officials of all nationalities—the red-faced, snub-nosed Hollander, the oily Portuguese half-caste—thrust or wormed their way through the crowd to look. I seemed to smell corruption in the air. Here were the creatures who had fattened on the spoils. There in the field were the heroes who won them. Tammany Hall was defended by the Ironsides.

From these reflections I was recalled by a hand on my shoulder. A lanky, unshaven police sergeant grasped my arm. 'You are not an officer,' he said; 'you go this way with the common soldiers,' and he led me across the open space to where the men were formed in a column of fours. The crowd grinned: the cameras clicked again. I fell in with the soldiers and seized the opportunity to tell them not to laugh or smile, but to appear serious men who cared for the cause they fought for; and when I saw how readily they took the hint, and what influence I possessed with them, it seemed to me that perhaps with two thousand prisoners something some day might be done. But presently a superior official—superior in rank alone, for in other respects he looked a miserable creature—came up and led me back to the officers. At last, when the crowd had thoroughly satisfied their patriotic curiosity, we were marched off; the soldiers to the enclosed camp on the racecourse, the officers to the States Model Schools prison.

The distance was short, so far as we were concerned, and surrounded by an escort of three armed policemen to each officer, we swiftly traversed two sandy avenues with detached houses on either hand, and reached our destination. We turned a corner; on the other side of the road stood a long, low, red brick building with a slated verandah and a row of iron railings before it. The verandah was crowded with bearded men in khaki uniforms or brown suits of flannel—smoking, reading, or talking. They looked up as we arrived. The iron gate was opened, and passing in we joined sixty British officers 'held by the enemy;' and the iron gate was then shut again.

'Hullo! How are you? Where did they catch you? What's the latest news of Buller's advance? Are we going to be exchanged?' and a dozen other questions were asked. It was the sort of reception accorded to a new boy at a private school, or, as it seemed to me, to a new arrival in hell. But after we had satisfied our friends in as much as we could, suggestions of baths, clothes, and luncheon were made which were very welcome. So we settled down to what promised to be a long and weary waiting.

The States Model Schools is a one-storied building of considerable size and solid structure, which occupies a corner formed by two roads through Pretoria. It consists of twelve large class-rooms, seven or eight of which were used by the British officers as dormitories and one as a dining-room; a large lecture-hall, which served as an improvised fives-court; and a well-fitted gymnasium. It stood in a quadrangular playground about one hundred and twenty yards square, in which were a dozen tents for the police guards, a cookhouse, two tents for the soldier servants, and a newly set-up bath-shed. I do not know how the arrival of other prisoners may have modified these arrangements, but at the time of my coming into the prison, there was room enough for everyone.

The Transvaal Government provided a daily ration of bully beef and groceries, and the prisoners were allowed to purchase from the local storekeeper, a Mr. Boshof, practically everything they cared to order, except alcoholic liquors. During the first week of my detention we requested that this last prohibition might be withdrawn, and after profound reflection and much doubtings, the President consented to countenance the buying of bottled beer. Until this concession was obtained our liquid refreshment would have satisfied the most immoderate advocate of temperance, and the only relief was found when the Secretary of State for War, a kind-hearted Portuguese, would smuggle in a bottle of whiskey hidden in his tail-coat pocket or amid a basket of fruit. A very energetic and clever young officer of the Dublin Fusiliers, Lieutenant Grimshaw, undertook the task of managing the mess, and when he was assisted by another subaltern—Lieutenant Southey, of the Royal Irish Fusiliers—this became an exceedingly well-conducted concern. In spite of the high prices prevailing in Pretoria—prices which were certainly not lowered for our benefit—the somewhat meagre rations which the Government allowed were supplemented, until we lived, for three shillings a day, quite as well as any regiment on service.

On arrival, every officer was given a new suit of clothes, bedding, towels, and toilet necessaries, and the indispensable Mr, Boshof was prepared to add to this wardrobe whatever might be required on payment either in money or by a cheque on Messrs. Cox & Co., whose accommodating fame had spread even to this distant hostile town. I took an early opportunity to buy a suit of tweeds of a dark neutral colour, and as unlike the suits of clothes issued by the Government as possible. I would also have purchased a hat, but another officer told me that he had asked for one and had been refused. After all, what use could I find for a hat, when there were plenty of helmets to spare if I wanted to Walk in the courtyard? And yet my taste ran towards a slouch hat.

The case of the soldiers was less comfortable than ours. Their rations were very scanty: only one pound of bully beef once a week and two pounds of bread; the rest was made up with mealies, potatoes, and such-like—and not very much of them. Moreover, since they had no money of their own, and since prisoners of war received no pay, they were unable to buy even so much as a pound of tobacco. In consequence they complained a good deal, and were, I think, sufficiently discontented to require nothing but leading to make them rise against their guards.

The custody and regulating of the officers were entrusted to a board of management, four of whose members visited us frequently and listened to any complaints or requests. M. de Souza, the Secretary of War, was perhaps the most friendly and obliging of these, and I think we owed most of the indulgences to his representations. He was a far-seeing little man who had travelled to Europe, and had a very clear conception of the relative strengths of Britain and the Transvaal. He enjoyed a lucrative and influential position under the Government, and was therefore devoted to its interests, but he was nevertheless suspected by the Inner Ring of Hollanders and the Relations of the President of having some sympathy for the British. He had therefore to be very careful. Commandant Opperman, who was directly responsible for our safe custody, was in times of peace a Landrost or Justice. He was too fat to go and fight, but he was an honest and patriotic Boer, who would have gladly taken an active part in the war. He firmly believed that the Republics would win, and when, as sometimes happened, bad news reached Pretoria, Opperman looked a picture of misery, and would come to us and speak of his resolve to shoot his wife and children and perish in the defence of the capital. Dr. Gunning was an amiable little Hollander, fat, rubicund, and well educated. He was a keen politician, and much attached to the Boer Government, which paid him an excellent salary for looking after the State Museum. He had a wonderful collection of postage stamps, and was also engaged in forming a Zoological Garden. This last ambition had just before the war led him into most serious trouble, for he was unable to resist the lion which Mr. Rhodes had offered him. He confided to me that the President had spoken 'most harshly' to him in consequence, and had peremptorily ordered the immediate return of the beast under threats of instant dismissal. Gunning said that he could not have borne such treatment, but that after all a man must live. My private impression is that he will acquiesce in any political settlement which leaves him to enlarge his museum undisturbed. But whether the Transvaal will be able to indulge in such luxuries, after blowing up many of other people's railway bridges, is a question which I cannot answer.

The fourth member of the Board, Mr. Malan, was a foul and objectionable brute. His personal courage was better suited to insulting the prisoners in Pretoria than to fighting the enemy at the front. He was closely related to the President, but not even this advantage could altogether protect him from taunts of cowardice, which were made even in the Executive Council, and somehow filtered down to us. On one occasion he favoured me with some of his impertinence; but I reminded him that in war either side may win, and asked whether he was wise to place himself in a separate category as regards behaviour to the prisoners. 'Because,' quoth I, 'it might be so convenient to the British Government to be able to make one or two examples.' He was a great gross man, and his colour came and went on a large over-fed face; so that his uneasiness was obvious. He never came near me again, but some days later the news of a Boer success arrived, and on the strength of this he came to the prison and abused a subaltern in the Dublin Fusiliers, telling him that he was no gentleman, and other things which it is not right to say to a prisoner. The subaltern happens to be exceedingly handy with his fists, so that after the war is over Mr. Malan is going to get his head punched quite independently of the general settlement.

Although, as I have frequently stated, there were no legitimate grounds of complaint against the treatment of British regular officers while prisoners of war, the days I passed at Pretoria were the most monotonous and among the most miserable of my life. Early in the sultry mornings, for the heat at this season of the year was great, the soldier servants—prisoners like ourselves—would bring us a cup of coffee, and sitting up in bed we began to smoke the cigarettes and cigars of another idle, aimless day. Breakfast was at nine: a nasty uncomfortable meal. The room was stuffy, and there are more enlivening spectacles than seventy British officers caught by Dutch farmers and penned together in confinement. Then came the long morning, to be killed somehow by reading, chess, or cards—and perpetual cigarettes. Luncheon at one: the same as breakfast, only more so; and then a longer afternoon to follow a long morning. Often some of the officers used to play rounders in the small yard which we had for exercise. But the rest walked moodily up and down, or lounged over the railings and returned the stares of the occasional passers-by. Later would come the 'Volksstem'—permitted by special indulgence—with its budget of lies.

Sometimes we get a little fillip of excitement. One evening, as I was leaning over the railings, more than forty yards from the nearest sentry, a short man with a red moustache walked quickly down the street, followed by two colley dogs. As he passed, but without altering his pace in the slightest, or even looking towards me, he said quite distinctly 'Methuen beat the Boers to hell at Belmont.' That night the air seemed cooler and the courtyard larger. Already we imagined the Republics collapsing and the bayonets of the Queen's Guards in the streets of Pretoria. Next day I talked to the War Secretary. I had made a large map upon the wall and followed the course of the war as far as possible by making squares of red and green paper to represent the various columns. I said: 'What about Methuen? He has beaten you at Belmont. Now he should be across the Modder. In a few days he will relieve Kimberley.' De Souza shrugged his shoulders. 'Who can tell?' he replied; 'but,' he put his finger on the map, 'there stands old Piet Cronje in a position called Scholz Nek, and we don't think Methuen will ever get past him.' The event justified his words, and the battle which we call Magersfontein (and ought to call 'Maasfontayne') the Boers call Scholz Nek.

Long, dull, and profitless were the days. I could not write, for the ink seemed to dry upon the pen. I could not read with any perseverance, and during the whole month I was locked up, I only completed Carlyle's 'History of Frederick the Great' and Mill's 'Essay on Liberty,' neither of which satisfied my peevish expectations. When at last the sun sank behind the fort upon the hill and twilight marked the end of another wretched day, I used to walk up and down the courtyard looking reflectively at the dirty, unkempt 'zarps' who stood on guard, racking my brains to find some way, by force or fraud, by steel or gold, of regaining my freedom. Little did these Transvaal Policemen think, as they leaned on their rifles, smoking and watching the 'tame officers,' of the dark schemes of which they were the object, or of the peril in which they would stand but for the difficulties that lay beyond the wall. For we would have made short work of them and their weapons any misty night could we but have seen our way clear after that.

As the darkness thickened, the electric lamps were switched on and the whole courtyard turned blue-white with black velvet shadows. Then the bell clanged, and we crowded again into the stifling dining hall for the last tasteless meal of the barren day. The same miserable stories were told again and again—Colonel Moller's surrender after Talana Hill, and the white flag at Nicholson's Nek—until I knew how the others came to Pretoria as well as I knew my own story.

'We never realised what had happened until we were actually prisoners,' said the officers of the Dublin Fusiliers Mounted Infantry, who had been captured with Colonel Moller on October 20. 'The "cease fire" sounded: no one knew what had happened. Then we were ordered to form up at the farmhouse, and there we found Boers, who told us to lay down our arms: we were delivered into their hands and never even allowed to have a gallop for freedom. But wait for the Court of Inquiry.'

I used always to sit next to Colonel Carleton at dinner, and from him and from the others learned the story of Nicholson's Nek, which it is not necessary to repeat here, but which filled me with sympathy for the gallant commander and soldiers who were betrayed by the act of an irresponsible subordinate. The officers of the Irish Fusiliers told me of the amazement with which they had seen the white flag flying. 'We had still some ammunition,' they said; 'it is true the position was indefensible—but we only wanted to fight it out.'

'My company was scarcely engaged,' said one poor captain, with tears of vexation in his eyes at the memory; and the Gloucesters told the same tale.

'We saw the hateful thing flying. The firing stopped. No one knew by whose orders the flag had been hoisted. While we doubted the Boers were all among us disarming the men.'

I will write no more upon these painful subjects except to say this, that the hoisting of a white flag in token of surrender is an act which can be justified only by clear proof that there was no prospect of gaining the slightest military advantage by going on fighting; and that the raising of a white flag in any case by an unauthorised person—i.e. not the officer in chief command—in such a manner as to compromise the resistance of a force, deserves sentence of death, though in view of the high standard of discipline and honour prevailing in her Majesty's army, it might not be necessary to carry the sentence into effect. I earnestly trust that in justice to gallant officers and soldiers, who have languished these weary months in Pretoria, there will be a strict inquiry into the circumstances under which they became prisoners of war. I have no doubt we shall be told that it is a foolish thing to wash dirty linen in public; but much better wash it in public than wear it foul.

One day shortly after I had arrived I had an interesting visit, for de Souza, wishing to have an argument brought Mr. Grobelaar to see me. This gentleman was the Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and had just returned from Mafeking, whither he had been conducting a 6-inch gun. He was a very well-educated person, and so far as I could tell, honest and capable besides. With him came Reuter's Agent, Mr. Mackay, and the odious Malan. I received them sitting on my bed in the dormitory, and when they had lighted cigars, of which I always kept a stock, we had a regular durbar. I began:

'Well, Mr. Grobelaar, you see how your Government treats representatives of the Press.'

Grobelaar. 'I hope you have nothing to complain of

Self. 'Look at the sentries with loaded rifles on every side. I might be a wild beast instead of a special correspondent.'

Grobelaar. 'Ah, but putting aside the sentries with loaded rifles, you do not, I trust, Mr. Churchill, make any complaint.'

Self. 'My chief objection to this place is that I am in it.'

Grobelaar. 'That of course is your misfortune, and Mr. Chamberlain's fault.

Self. 'Not at all. We are a peace-loving people, but we had no choice but to fight or be—what was it your burghers told me in the camps?—"driven into the sea." The responsibility of the war is upon you and your President.'

Grobelaar. 'Don't you believe that. We did not want to fight. We only wanted to be left alone.'

Self. 'You never wanted war?'

de Souza. 'Ah, my God, no! Do you think we would fight Great Britain for amusement?'

Self. 'Then why did you make every preparation—turn the Republics into armed camps—prepare deep-laid plans for the invasion of our Colonies?'

Grobelaar. 'Why, what could we do after the Jameson Raid? We had to be ready to protect ourselves.'

Self. 'Surely less extensive armaments would have been sufficient to guard against another similar inroad.'

Grobelaar. 'But we knew your Government was behind the Raiders. Jameson was in front, but Rhodes and your Colonial Office were at his elbow.'

Self. 'As a matter of fact no two people were more disconcerted by the Raid than Chamberlain and Rhodes. Besides, the British Government disavowed the Raiders' action and punished the Raiders, who, I am quite prepared to admit, got no more than they deserved.'

de Souza. 'I don't complain about the British Government's action at the time of the Raid. Chamberlain behaved very honourably then. But it was afterwards, when Rhodes was not punished, that we knew it was all a farce, and that the British Government was bent on our destruction. When the burghers knew that Rhodes was not punished they lost all trust in England.'

Malan. 'Ya, ya. That Rhodes, he is the ... at the bottom of it all. You wait and see what we will do to Rhodes when we take Kimberley.'

Self. 'Then you maintain, de Souza, that the distrust caused in this country by the fact that Rhodes was not punished—though how you can punish a man who breaks no law I cannot tell—was the sole cause of your Government making these gigantic military preparations, because it is certain that these preparations were the actual cause of war.'

Grobelaar. 'Why should they be a cause of war? We would never have attacked you.'

Self. 'But at this moment you are invading Cape Colony and Natal, while no British soldier has set foot on Republican soil. Moreover, it was you who declared war upon us.'

Grobelaar. 'Naturally we were not such fools as to wait till your army was here. As soon as you began to send your army, we were bound to declare war. If you had sent it earlier we should have fought earlier. Really, Mr. Churchill, you must see that is only common sense.'

Self. 'I am not criticising your policy or tactics. You hated us bitterly—I dare say you had cause to. You made tremendous preparations—I don't say you were wrong—but look at it from our point of view. We saw a declared enemy armed and arming. Against us, and against us alone, could his preparations be directed. It was time we took some precautions: indeed, we were already too late. Surely what has happened at the front proves that we had no designs against you. You were ready. We were unready. It is the wolf and lamb if you like; but the wolf was asleep and never before was a lamb with such teeth and claws.'

Grobelaar. 'Do you really mean to say that we forced this war on you, that you did not want to fight us?'

Self. 'The country did not wish for war with the Boers. Personally, I have always done so. I saw that you had six rifles to every burgher in the Republic. I knew what that meant. It meant that you were going to raise a great Afrikander revolt against us. One does not set extra places at table unless one expects company to dinner. On the other hand, we have affairs all over the world, and at any moment may become embroiled with a European power. At this time things are very quiet. The board is clear in other directions. We can give you our undivided attention. Armed and ambitious as you were, the war had to come sooner or later. I have always said "sooner." Therefore, I rejoiced when you sent your ultimatum and roused the whole nation.'

Malan. 'You don't rejoice quite so much now.'

Self. 'My opinion is unaltered, except that the necessity for settling the matter has become more apparent. As for the result, that, as I think Mr. Grobelaar knows, is only a question of time and money expressed in terms of blood and tears.'

Grobelaar. 'No: our opinion is quite unchanged. We prepared for the war. We have always thought we could beat you. We do not doubt our calculations now. We have done better even than we expected. The President is extremely pleased.'

Self. 'There is no good arguing on that point. We shall have to fight it out. But if you had tried to keep on friendly terms with us, the war would not have come for a long time; and the delay was all on your side.'

Grobelaar. 'We have tried till we are sick of it. This Government was badgered out of its life with Chamberlain's despatches—such despatches. And then look how we have been lied about in your papers, and called barbarians and savages.'

Self. 'I think you have certainly been abused unjustly. Indeed, when I was taken prisoner the other day, I thought it quite possible I should be put to death, although I was a correspondent' (great laughter, 'Fancy that!' etc.). 'At the best I expected to be held in prison as a kind of hostage. See how I have been mistaken.'

I pointed at the sentry who stood in the doorway, for even members of the Government could not visit us alone. Grobelaar flushed. 'Oh, well, we will hope that the captivity will not impair your spirits. Besides, it will not last long. The President expects peace before the New Year.'

'I shall hope to be free by then.'

And with this the interview came to an end, and my visitors withdrew. The actual conversation had lasted more than an hour, but the dialogue above is not an inaccurate summary.

About ten days after my arrival at Pretoria I received a visit from the American Consul, Mr. Macrum. It seems that some uncertainty prevailed at home as to whether I was alive, wounded or unwounded, and in what light I was regarded by the Transvaal authorities. Mr. Bourke Cockran, an American Senator who had long been a friend of mine, telegraphed from New York to the United States representative in Pretoria, hoping by this neutral channel to learn how the case stood. I had not, however, talked with Mr. Macrum for very long before I realised that neither I nor any other British prisoner was likely to be the better for any efforts which he might make on our behalf. His sympathies were plainly so much with the Transvaal Government that he even found it difficult to discharge his diplomatic duties. However, he so far sank his political opinions as to telegraph to Mr. Bourke Cockran, and the anxiety which my relations were suffering on my account was thereby terminated.

I had one other visitor in these dull days, whom I should like to notice. During the afternoon which I spent among the Boers in their camp behind Bulwana Hill I had exchanged a few words with an Englishman whose name is of no consequence, but who was the gunner entrusted with the aiming of the big 6-inch gun. He was a light-hearted jocular fellow outwardly, but I was not long in discovering that his anxieties among the Boers were grave and numerous. He had been drawn into the war, so far as I could make out, more by the desire of sticking to his own friends and neighbours than even of preserving his property. But besides this local spirit, which counterbalanced the racial and patriotic feelings, there was a very strong desire to be upon the winning side, and I think that he regarded the Boers with an aversion which increased in proportion as their successes fell short of their early anticipations. One afternoon he called at the States Model Schools prison and, being duly authorised to visit the prisoners, asked to see me. In the presence of Dr. Gunning, I had an interesting interview. At first our conversation was confined to generalities, but gradually, as the other officers in the room, with ready tact, drew the little Hollander Professor into an argument, my renegade and I were able to exchange confidences.

I was of course above all things anxious to get true news from the outer world, and whenever Dr. Gunning's attention was distracted by his discussion with the officers, I managed to get a little.

'Well, you know,' said the gunner, 'you English don't play fair at Ladysmith at all. We have allowed you to have a camp at Intombi Spruit for your wounded, and yet we see red cross flags flying in the town, and we have heard that in the Church there is a magazine of ammunition protected by the red cross flag. Major Erasmus, he says to me "John, you smash up that building," and so when I go back I am going to fire into the church.' Gunning broke out into panegyrics on the virtues of the Afrikanders: my companion dropped his voice. 'The Boers have had a terrible beating at Belmont; the Free Staters have lost more than 200 killed; much discouraged; if your people keep on like this the Free State will break up.' He raised his voice, 'Ladysmith hold out a month? Not possible; we shall give it a fortnight's more bombardment, and then you will just see how the burghers will scramble into their trenches. Plenty of whisky then, ha, ha, ha!' Then lower, 'I wish to God I could get away from this, but I don't know what to do; they are always suspecting me and watching me, and I have to keep on pretending I want them to win. This is a terrible position for a man to be in: curse the filthy Dutchmen!'

I said, 'Will Methuen get to Kimberley?'

'I don't know, but he gave them hell at Belmont and at Graspan, and they say they are fighting again to-day at Modder River. Major Erasmus is very down-hearted about it. But the ordinary burghers hear nothing but lies; all lies, I tell you. (Crescendo) Look at the lies that have been told about us! Barbarians! savages! every name your papers have called us, but you know better than that now; you know how well we have treated you since you have been a prisoner; and look at the way your people have treated our prisoners—put them on board ship to make them sea-sick! Don't you call that cruel?' Here Gunning broke in that it was time for visitors to leave the prison. And so my strange guest, a feather blown along by the wind, without character or stability, a renegade, a traitor to his blood and birthplace, a time-server, had to hurry away. I took his measure; nor did his protestations of alarm excite my sympathy, and yet somehow I did not feel unkindly towards him; a weak man is a pitiful object in times of trouble. Some of our countrymen who were living in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State at the outbreak of the war have been placed in such difficult positions and torn by so many conflicting emotions that they must be judged very tolerantly. How few men are strong enough to stand against the prevailing currents of opinion! Nor, after the desertion of the British residents in the Transvaal in 1881, have we the right to judge their successors harshly if they have failed us, for it was Great and Mighty Britain who was the renegade and traitor then.

No sooner had I reached Pretoria than I demanded my release from the Government, on the grounds that I was a Press correspondent and a non-combatant. So many people have found it difficult to reconcile this position with the accounts which have been published of what transpired during the defence of the armoured train, that I am compelled to explain. Besides the soldiers of the Dublin Fusiliers and Durban Light Infantry who had been captured, there were also eight or ten civilians, including a fireman, a telegraphist, and several men of the breakdown gang. Now it seems to me that according to international practice and the customs of war, the Transvaal Government were perfectly justified in regarding all persons connected with a military train as actual combatants; indeed, the fact that they were not soldiers was, if anything, an aggravation of their case. But the Boers were at that time overstocked with prisoners whom they had to feed and guard, and they therefore announced that the civilians would be released as soon as their identity was established, and only the military retained as prisoners.

In my case, however, an exception was to be made, and General Joubert, who had read the gushing accounts of my conduct which appeared in the Natal newspapers, directed that since I had taken part in the fighting I was to be treated as a combatant officer.

Now, as it happened, I had confined myself strictly to the business of clearing the line, which was entrusted to me, and although I do not pretend that I considered the matter in its legal aspect at the time, the fact remains that I did not give a shot, nor was I armed when captured. I therefore claimed to be included in the same category as the civilian railway officials and men of the breakdown gang, whose declared duty it was to clear the line, pointing out that though my action might differ in degree from theirs, it was of precisely the same character, and that if they were regarded as non-combatants I had a right to be considered a non-combatant too.

To this effect I wrote two letters, one to the Secretary of War and one to General Joubert; but, needless to say, I did not indulge in much hope of the result, for I was firmly convinced that the Boer authorities regarded me as a kind of hostage, who would make a pleasing addition to the collection of prisoners they were forming against a change of fortune. I therefore continued to search for a path of escape; and indeed it was just as well that I did so, for I never received any answer to either of my applications while I was a prisoner, although I have since heard that one arrived by a curious coincidence the very day after I had departed.

While I was looking about for means, and awaiting an opportunity to break out of the Model Schools, I made every preparation to make a graceful exit when the moment should arrive. I gave full instructions to my friends as to what was to be done with my clothes and the effects I had accumulated during my stay; I paid my account to date with the excellent Boshof; cashed a cheque on him for 20l.; changed some of the notes I had always concealed on my person since my capture into gold; and lastly, that there might be no unnecessary unpleasantness, I wrote the following letter to the Secretary of State:

States Model Schools Prison: December 10, 1899.

Sir,—I have the honour to inform you that as I do not consider that your Government have any right to detain me as a military prisoner, I have decided to escape from your custody. I have every confidence in the arrangements I have made with my friends outside, and I do not therefore expect to have another opportunity of seeing you. I therefore take this occasion to observe that I consider your treatment of prisoners is correct and humane, and that I see no grounds for complaint. When I return to the British lines I will make a public statement to this effect. I have also to thank you personally for your civility to me, and to express the hope that we may meet again at Pretoria before very long, and under different circumstances. Regretting that I am unable to bid you a more ceremonious or a personal farewell,

I have the honour, to be, Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

WINSTON CHURCHILL.To Mr. de Souza,

Secretary of War, South African Republic.I arranged that this letter, which I took great pleasure in writing, should be left on my bed, and discovered so soon as my flight was known.

It only remained now to find a hat. Luckily for me Mr. Adrian Hofmeyr, a Dutch clergyman and pastor of Zeerust, had ventured before the war to express opinions contrary to those which the Boers thought befitting for a Dutchman to hold. They had therefore seized him on the outbreak of hostilities, and after much ill-treatment and many indignities on the Western border, brought him to the States Schools. He knew most of the officials, and could, I think, easily have obtained his liberty had he pretended to be in sympathy with the Republics. He was, however, a true man, and after the clergyman of the Church of England, who was rather a poor creature, omitted to read the prayer for the Queen one Sunday, it was to Hofmeyr's evening services alone that most of the officers would go. I borrowed his hat.

I ESCAPE FROM THE BOERS

Lourenço Marques: December 22, 1899,

How unhappy is that poor man who loses his liberty! What can the wide world give him in exchange? No degree of material comfort, no consciousness of correct behaviour, can balance the hateful degradation of imprisonment. Before I had been an hour in captivity, as the previous pages evidence, I resolved to escape. Many plans suggested themselves, were examined, and rejected. For a month I thought of nothing else. But the peril and difficulty restrained action. I think that it was the report of the British defeat at Stormberg that clinched the matter. All the news we heard in Pretoria was derived from Boer sources, and was hideously exaggerated and distorted. Every day we read in the 'Volksstem'—probably the most astounding tissue of lies ever presented to the public under the name of a newspaper—of Boer victories and of the huge slaughters and shameful flights of the British. However much one might doubt and discount these tales, they made a deep impression. A month's feeding on such literary garbage weakens the constitution of the mind. We wretched prisoners lost heart. Perhaps Great Britain would not persevere; perhaps Foreign Powers would intervene; perhaps there would be another disgraceful, cowardly peace. At the best the war and our confinement would be prolonged for many months. I do not pretend that impatience at being locked up was not the foundation of my determination; but I should never have screwed up my courage to make the attempt without the earnest desire to do something, however small, to help the British cause. Of course, I am a man of peace. I did not then contemplate becoming an officer of Irregular Horse. But swords are not the only weapons in the world. Something may be done with a pen. So I determined to take all hazards; and, indeed, the affair was one of very great danger and difficulty.

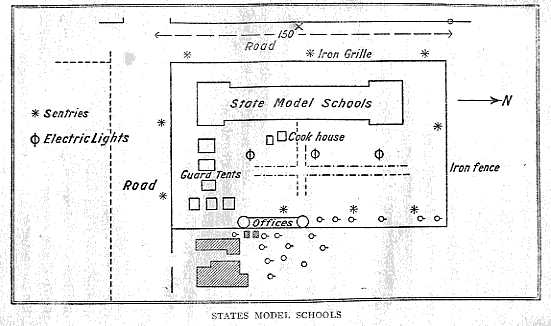

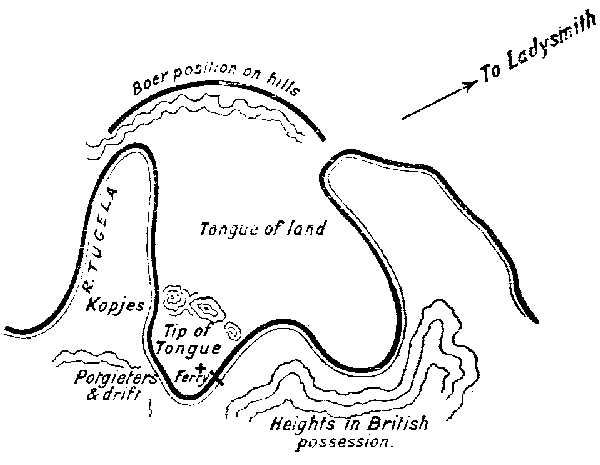

The States Model Schools stand in the midst of a quadrangle, and are surrounded on two sides by an iron grille and on two by a corrugated iron fence about 10 ft. high. These boundaries offered little obstacle to anyone who possessed the activity of youth, but the fact that they were guarded on the inside by sentries, fifty yards apart, armed with rifle and revolver, made them a well-nigh insuperable barrier. No walls are so hard to pierce as living walls. I thought of the penetrating power of gold, and the sentries were sounded. They were incorruptible. I seek not to deprive them of the credit, but the truth is that the bribery market in the Transvaal has been spoiled by the millionaires. I could not afford with my slender resources to insult them heavily enough. So nothing remained but to break out in spite of them. With another officer who may for the present—since he is still a prisoner—remain nameless, I formed a scheme.

PLAN OF STATES MODEL SCHOOLS

After anxious reflection and continual watching, it was discovered that when the sentries near the offices walked about on their beats they were at certain moments unable to see the top of a few yards of the wall. The electric lights in the middle of the quadrangle brilliantly lighted the whole place but cut off the sentries beyond them from looking at the eastern wall, for from behind the lights all seemed darkness by contrast. The first thing was therefore to pass the two sentries near the offices. It was necessary to hit off the exact moment when both their backs should be turned together. After the wall was scaled we should be in the garden of the villa next door. There our plan came to an end. Everything after this was vague and uncertain. How to get out of the garden, how to pass unnoticed through the streets, how to evade the patrols that surrounded the town, and above all how to cover the two hundred and eighty miles to the Portuguese frontiers, were questions which would arise at a later stage. All attempts to communicate with friends outside had failed. We cherished the hope that with chocolate, a little Kaffir knowledge, and a great deal of luck, we might march the distance in a fortnight, buying mealies at the native kraals and lying hidden by day. But it did not look a very promising prospect.

We determined to try on the night of the 11th of December, making up our minds quite suddenly in the morning, for these things are best done on the spur of the moment. I passed the afternoon in positive terror. Nothing, since my schooldays, has ever disturbed me so much as this. There is something appalling in the idea of stealing secretly off in the night like a guilty thief. The fear of detection has a pang of its own. Besides, we knew quite well that on occasion, even on excuse, the sentries would fire. Fifteen yards is a short range. And beyond the immediate danger lay a prospect of severe hardship and suffering, only faint hopes of success, and the probability at the best of five months in Pretoria Gaol.

The afternoon dragged tediously away. I tried to read Mr. Lecky's 'History of England,' but for the first time in my life that wise writer wearied me. I played chess and was hopelessly beaten. At last it grew dark. At seven o'clock the bell for dinner rang and the officers trooped off. Now was the time. But the sentries gave us no chance. They did not walk about. One of them stood exactly opposite the only practicable part of the wall. We waited for two hours, but the attempt was plainly impossible, and so with a most unsatisfactory feeling of relief to bed.

Tuesday, the 12th! Another day of fear, but fear crystallising more and more into desperation. Anything was better than further suspense. Night came again. Again the dinner bell sounded. Choosing my opportunity I strolled across the quadrangle and secreted myself in one of the offices. Through a chink I watched the sentries. For half an hour they remained stolid and obstructive. Then all of a sudden one turned and walked up to his comrade and they began to talk. Their backs were turned. Now or never. I darted out of my hiding place and ran to the wall, seized the top with my hands and drew myself up. Twice I let myself down again in sickly hesitation, and then with a third resolve scrambled up. The top was flat. Lying on it I had one parting glimpse of the sentries, still talking, still with their backs turned; but, I repeat, fifteen yards away. Then I lowered myself silently down into the adjoining garden and crouched among the shrubs. I was free. The first step had been taken, and it was irrevocable.

It now remained to await the arrival of my comrade. The bushes of the garden gave a good deal of cover, and in the moonlight their shadows lay black on the ground. Twenty yards away was the house, and I had not been five minutes in hiding before I perceived that it was full of people; the windows revealed brightly lighted rooms, and within I could see figures moving about. This was a fresh complication. We had always thought the house unoccupied. Presently—how long afterwards I do not know, for the ordinary measures of time, hours, minutes, and seconds are quite meaningless on such occasions—a man came out of the door and walked across the garden in my direction. Scarcely ten yards away he stopped and stood still, looking steadily towards me. I cannot describe the surge of panic which nearly overwhelmed me. I must be discovered. I dared not stir an inch. My heart beat so violently that I felt sick. But amid a tumult of emotion, reason, seated firmly on her throne, whispered, 'Trust to the dark background.' I remained absolutely motionless. For a long time the man and I remained opposite each other, and every instant I expected him to spring forward. A vague idea crossed my mind that I might silence him. 'Hush, I am a detective. We expect that an officer will break out here to-night. I am waiting to catch him.' Reason—scornful this time—replied: 'Surely a Transvaal detective would speak Dutch. Trust to the shadow.' So I trusted, and after a spell another man came out of the house, lighted a cigar, and both he and the other walked off together. No sooner had they turned than a cat pursued by a dog rushed into the bushes and collided with me. The startled animal uttered a 'miaul' of alarm and darted back again, making a horrible rustling. Both men stopped at once. But it was only the cat, as they doubtless observed, and they passed out of the garden gate into the town.

I looked at my watch. An hour had passed since I climbed the wall. Where was my comrade? Suddenly I heard a voice from within the quadrangle say, quite loud, 'All up.' I crawled back to the wall. Two officers were walking up and down the other side jabbering Latin words, laughing and talking all manner of nonsense—amid which I caught my name. I risked a cough. One of the officers immediately began to chatter alone. The other said slowly and clearly, '... cannot get out. The sentry suspects. It's all up. Can you get back again?' But now all my fears fell from me at once. To go back was impossible. I could not hope to climb the wall unnoticed. Fate pointed onwards. Besides, I said to myself, 'Of course, I shall be recaptured, but I will at least have a run for my money.' I said to the officers, 'I shall go on alone.'

Now I was in the right mood for these undertakings—that is to say that, thinking failure almost certain, no odds against success affected me. All risks were less than the certainty. A glance at the plan (p. 182) will show that the rate which led into the road was only a few yards from another sentry. I said to myself, 'Toujours de l'audace:' put my hat on my head, strode into the middle of the garden, walked past the windows of the house without any attempt at concealment, and so went through the gate and turned to the left. I passed the sentry at less than five yards. Most of them knew me by sight. Whether he looked at me or not I do not know, for I never turned my head. But after walking a hundred yards and hearing no challenge, I knew that the second obstacle had been surmounted. I was at large in Pretoria.

I walked on leisurely through the night humming a tune and choosing the middle of the road. The streets were full of Burghers, but they paid no attention to me. Gradually I reached the suburbs, and on a little bridge I sat down to reflect and consider. I was in the heart of the enemy's country. I knew no one to whom I could apply for succour. Nearly three hundred miles stretched between me and Delagoa Bay. My escape must be known at dawn. Pursuit would be immediate. Yet all exits were barred. The town was picketed, the country was patrolled, the trains were searched, the line was guarded. I had 75l. in my pocket and four slabs of chocolate, but the compass and the map which might have guided me, the opium tablets and meat lozenges which should have sustained me, were in my friend's pockets in the States Model Schools. Worst of all, I could not speak a word of Dutch or Kaffir, and how was I to get food or direction?

But when hope had departed, fear had gone as well. I formed a plan. I would find the Delagoa Bay Railway. Without map or compass I must follow that in spite of the pickets. I looked at the stars. Orion shone brightly. Scarcely a year ago he had guided me when lost in the desert to the banks of the Nile. He had given me water. Now he should lead to freedom. I could not endure the want of either.

After walking south for half a mile, I struck the railroad. Was it the line to Delagoa Bay or the Pietersburg branch? If it were the former it should run east. But so far as I could see this line ran northwards. Still, it might be only winding its way out among the hills. I resolved to follow it. The night was delicious. A cool breeze fanned my face and a wild feeling of exhilaration took hold of me. At any rate, I was free, if only for an hour. That was something. The fascination of the adventure grew. Unless the stars in their courses fought for me I could not escape. Where, then, was the need of caution? I marched briskly along the line. Here and there the lights of a picket fire gleamed. Every bridge had its watchers. But I passed them all, making very short detours at the dangerous places, and really taking scarcely any precautions. Perhaps that was the reason I succeeded.

As I walked I extended my plan. I could not march three hundred miles to the frontier. I would board a train in motion and hide under the seats, on the roof, on the couplings—anywhere. What train should I take? The first, of course. After walking for two hours I perceived the signal lights of a station. I left the line, and, circling round it, hid in the ditch by the track about 200 yards beyond it. I argued that the train would stop at the station and that it would not have got up too much speed by the time it reached me. An hour passed. I began to grow impatient. Suddenly I heard the whistle and the approaching rattle. Then the great yellow head lights of the engine flashed into view. The train waited five minutes at the station and started again with much noise and steaming. I crouched by the track. I rehearsed the act in my mind. I must wait until the engine had passed, otherwise I should be seen. Then I must make a dash for the carriages.

The train started slowly, but gathered speed sooner than I had expected. The flaring lights drew swiftly near. The rattle grew into a roar. The dark mass hung for a second above me. The engine-driver silhouetted against his furnace glow, the black profile of the engine, the clouds of steam rushed past. Then I hurled myself on the trucks, clutched at something, missed, clutched again, missed again, grasped some sort of hand-hold, was swung off my feet—my toes bumping on the line, and with a struggle seated myself on the couplings of the fifth truck from the front of the train. It was a goods train, and the trucks were full of sacks, soft sacks covered with coal dust. I crawled on top and burrowed in among them. In five minutes I was completely buried. The sacks were warm and comfortable. Perhaps the engine-driver had seen me rush up to the train and would give the alarm at the next station: on the other hand, perhaps not. Where was the train going to? Where would it be unloaded? Would it be searched? Was it on the Delagoa Bay line? What should I do in the morning? Ah, never mind that. Sufficient for the day was the luck thereof. Fresh plans for fresh contingencies. I resolved to sleep, nor can I imagine a more pleasing lullaby than the clatter of the train that carries you at twenty miles an hour away from the enemy's capital.

How long I slept I do not know, but I woke up suddenly with all feelings of exhilaration gone, and only the consciousness of oppressive difficulties heavy on me. I must leave the train before daybreak, so that I could drink at a pool and find some hiding-place while it was still dark. Another night I would board another train. I crawled from my cosy hiding-place among the sacks and sat again on the couplings. The train was running at a fair speed, but I felt it was time to leave it. I took hold of the iron handle at the back of the truck, pulled strongly with my left hand, and sprang. My feet struck the ground in two gigantic strides, and the next instant I was sprawling in the ditch, considerably shaken but unhurt. The train, my faithful ally of the night, hurried on its journey.

It was still dark. I was in the middle of a wide valley, surrounded by low hills, and carpeted with high grass drenched in dew. I searched for water in the nearest gully, and soon found a clear pool. I was very thirsty, but long after I had quenched my thirst I continued to drink, that I might have sufficient for the whole day.

Presently the dawn began to break, and the sky to the east grew yellow and red, slashed across with heavy black clouds. I saw with relief that the railway ran steadily towards the sunrise. I had taken the right line, after all.

Having drunk my fill, I set out for the hills, among which I hoped to find some hiding-place, and as it became broad daylight I entered a small grove of trees which grew on the side of a deep ravine. Here I resolved to wait till dusk. I had one consolation: no one in the world knew where I was—I did not know myself. It was now four o'clock. Fourteen hours lay between me and the night. My impatience to proceed, while I was still strong, doubled their length. At first it was terribly cold, but by degrees the sun gained power, and by ten o'clock the heat was oppressive. My sole companion was a gigantic vulture, who manifested an extravagant interest in my condition, and made hideous and ominous gurglings from time to time. From my lofty position I commanded a view of the whole valley. A little tin-roofed town lay three miles to the westward. Scattered farmsteads, each with a clump of trees, relieved the monotony of the undulating ground. At the foot of the hill stood a Kaffir kraal, and the figures of its inhabitants dotted the patches of cultivation or surrounded the droves of goats and cows which fed on the pasture. The railway ran through the middle of the valley, and I could watch the passage of the various trains. I counted four passing each way, and from this I drew the conclusion that the same number would run by night. I marked a steep gradient up which they climbed very slowly, and determined at nightfall to make another attempt to board one of these. During the day I ate one slab of chocolate, which, with the heat, produced a violent thirst. The pool was hardly half a mile away, but I dared not leave the shelter of the little wood, for I could see the figures of white men riding or walking occasionally across the valley, and once a Boer came and fired two shots at birds close to my hiding-place. But no one discovered me.

The elation and the excitement of the previous night had burnt away, and a chilling reaction followed. I was very hungry, for I had had no dinner before starting, and chocolate, though it sustains, does not satisfy. I had scarcely slept, but yet my heart beat so fiercely and I was so nervous and perplexed about the future that I could not rest. I thought of all the chances that lay against me; I dreaded and detested more than words can express the prospect of being caught and dragged back to Pretoria. I do not mean that I would rather have died than have been retaken, but I have often feared death for much less. I found no comfort in any of the philosophical ideas which some men parade in their hours of ease and strength and safety. They seemed only fair-weather friends. I realised with awful force that no exercise of my own feeble wit and strength could save me from my enemies, and that without the assistance of that High Power which interferes in the eternal sequence of causes and effects more often than we are always prone to admit, I could never succeed. I prayed long and earnestly for help and guidance. My prayer, as it seems to me, was swiftly and wonderfully answered, I cannot now relate the strange circumstances which followed, and which changed my nearly hopeless position into one of superior advantage. But after the war is over I shall hope to lengthen this account, and so remarkable will the addition be that I cannot believe the reader will complain.

The long day reached its close at last. The western clouds flushed into fire; the shadows of the hills stretched out across the valley. A ponderous Boer waggon, with its long team, crawled slowly along the track towards the town. The Kaffirs collected their herds and drew around their kraal. The daylight died, and soon it was quite dark. Then, and not till then, I set forth, I hurried to the railway line, pausing on my way to drink at a stream of sweet, cold water. I waited for some time at the top of the steep gradient in the hope of catching a train. But none came, and I gradually guessed, and I have since found that I guessed right, that the train I had already travelled in was the only one that ran at night. At last I resolved to walk on, and make, at any rate, twenty miles of my journey. I walked for about six hours. How far I travelled I do not know, but I do not think that it was very many miles in the direct line. Every bridge was guarded by armed men; every few miles were gangers' huts; at intervals there were stations with villages clustering round them. All the veldt was bathed in the bright rays of the full moon, and to avoid these dangerous places I had to make wide circuits and often to creep along the ground. Leaving the railroad I fell into bogs and swamps, and brushed through high grass dripping with dew, so that I was drenched to the waist. I had been able to take little exercise during my month's imprisonment, and I was soon tired out with walking, as well as from want of food and sleep. I felt very miserable when I looked around and saw here and there the lights of houses, and thought of the warmth and comfort within them, but knew that they only meant danger to me. After six or seven hours of walking I thought it unwise to go further lest I should exhaust myself, so I lay down in a ditch to sleep. I was nearly at the end of my tether. Nevertheless, by the will of God, I was enabled to sustain myself during the next few days, obtaining food at great risk here and there, resting in concealment by day and walking only at night. On the fifth day I was beyond Middelburg, so far as I could tell, for I dared not inquire nor as yet approach the stations near enough to read the names. In a secure hiding-place I waited for a suitable train, knowing that there is a through service between Middelburg and Lourenço Marques.

Meanwhile there had been excitement in the States Model Schools, temporarily converted into a military prison. Early on Wednesday morning—barely twelve hours after I had escaped—my absence was discovered—I think by Dr. Gunning. The alarm was given. Telegrams with my description at great length were despatched along all the railways. Three thousand photographs were printed. A warrant was issued for my immediate arrest. Every train was strictly searched. Everyone was on the watch. The worthy Boshof, who knew my face well, was hurried off to Komati Poort to examine all and sundry people "with red hair" travelling towards the frontier. The newspapers made so much of the affair that my humble fortunes and my whereabouts were discussed in long columns of print, and even in the crash of the war I became to the Boers a topic all to myself. The rumours in part amused me. It was certain, said the "Standard and Diggers' News," that I had escaped disguised as a woman. The next day I was reported captured at Komati Poort dressed as a Transvaal policeman. There was great delight at this, which was only changed to doubt when other telegrams said that I had been arrested at Brugsbank, at Middelburg, and at Bronkerspruit. But the captives proved to be harmless people after all. Finally it was agreed that I had never left Pretoria. I had—it appeared—changed clothes with a waiter, and was now in hiding at the house of some British sympathiser in the capital. On the strength of this all the houses of suspected persons were searched from top to bottom, and these unfortunate people were, I fear, put to a great deal of inconvenience. A special commission was also appointed to investigate 'stringently' (a most hateful adjective in such a connection) the causes 'which had rendered it possible for the War Correspondent of the "Morning Post" to escape.'

The 'Volksstem' noticed as a significant fact that I had recently become a subscriber to the State Library, and had selected Mill's essay 'On Liberty.' It apparently desired to gravely deprecate prisoners having access to such inflammatory literature. The idea will, perhaps, amuse those who have read the work in question.

I find it very difficult in the face of the extraordinary efforts which were made to recapture me, to believe that the Transvaal Government seriously contemplated my release before they knew I had escaped them. Yet a telegram was swiftly despatched from Pretoria to all the newspapers, setting forth the terms of a most admirable letter, in which General Joubert explained the grounds which prompted him generously to restore my liberty. I am inclined to think that the Boers hate being beaten even in the smallest things, and always fight on the win, tie, or wrangle principle; but in my case I rejoice I am not beholden to them, and have not thus been disqualified from fighting.

All these things may provoke a smile of indifference, perhaps even of triumph, after the danger is past; but during the days when I was lying up in holes and corners, waiting for a good chance to board a train, the causes that had led to them preyed more than I knew on my nerves. To be an outcast, to be hunted, to lie under a warrant for arrest, to fear every man, to have imprisonment—not necessarily military confinement either—hanging overhead, to fly the light, to doubt the shadows—all these things ate into my soul and have left an impression that will not perhaps be easily effaced.

On the sixth day the chance I had patiently waited for came. I found a convenient train duly labelled to Lourenço Marques standing in a siding. I withdrew to a suitable spot for boarding it—for I dared not make the attempt in the station—and, filling a bottle with water to drink on the way, I prepared for the last stage of my journey.

The truck in which I ensconced myself was laden with great sacks of some soft merchandise, and I found among them holes and crevices by means of which I managed to work my way to the inmost recess. The hard floor was littered with gritty coal dust, and made a most uncomfortable bed. The heat was almost stifling. I was resolved, however, that nothing should lure or compel me from my hiding-place until I reached Portuguese territory. I expected the journey to take thirty-six hours; it dragged out into two and a half days. I hardly dared sleep for fear of snoring.

I dreaded lest the trucks should be searched at Komati Poort, and my anxiety as the train approached this neighbourhood was very great. To prolong it we were shunted on to a siding for eighteen hours either at Komati Poort or the station beyond it. Once indeed they began to search my truck, and I heard the tarpaulin rustle as they pulled at it, but luckily they did not search deep enough, so that, providentially protected, I reached Delagoa Bay at last, and crawled forth from my place of refuge and of punishment, weary, dirty, hungry, but free once more.

Thereafter everything smiled. I found my way to the British Consul, Mr. Ross, who at first mistook me for a fireman off one of the ships in the harbour, but soon welcomed me with enthusiasm. I bought clothes, I washed, I sat down to dinner with a real tablecloth and real glasses; and fortune, determined not to overlook the smallest detail, had arranged that the steamer 'Induna' should leave that very night for Durban. As soon as the news of my arrival spread about the town, I received many offers of assistance from the English residents, and lest any of the Boer agents with whom Lourenço Marques is infested should attempt to recapture me in neutral territory, nearly a dozen gentlemen escorted me to the steamer armed with revolvers. It is from the cabin of this little vessel, as she coasts along the sandy shores of Africa, that I write the concluding lines of this letter, and the reader who may persevere through this hurried account will perhaps understand why I write them with a feeling of triumph, and better than triumph, a feeling of pure joy.

BACK TO THE BRITISH LINES

Frere: December 24, 1899.

The voyage of the "Induna" from Delagoa Bay to Durban was speedy and prosperous, and on the afternoon of the 23rd we approached our port, and saw the bold headland that shields it rising above the horizon to the southward. An hour's steaming brought us to the roads. More than twenty great transports and supply vessels lay at anchor, while three others, crowded from end to end with soldiery, circled impatiently as they waited for pilots to take them into the harbour. Our small vessel was not long in reaching the jetty, and I perceived that a very considerable crowd had gathered to receive us. But it was not until I stepped on shore that I realised that I was myself the object of this honourable welcome. I will not chronicle the details of what followed. It is sufficient to say that many hundreds of the people of Durban took occasion to express their joy at my tiny pinch of triumph over the Boers, and that their enthusiasm was another sincere demonstration of their devotion to the Imperial cause, and their resolve to carry the war to an indisputable conclusion. After an hour of turmoil, which I frankly admit I enjoyed extremely, I escaped to the train, and the journey to Pietermaritzburg passed very quickly in the absorbing occupation of devouring a month's newpapers and clearing my palate from the evil taste of the exaggerations of Pretoria by a liberal antidote of our own versions. I rested a day at Government House, and enjoyed long conversations with Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson—the Governor under whose wise administration Natal has become the most patriotic province of the Empire. Moreover, I was fortunate in meeting Colonel Hime, the Prime Minister of the Colony, a tall, grey, keen-eyed man, who talked only of the importance of fighting this quarrel out to the end, and of the obstinate determination of the people he represented to stand by the Queen's Government through all the changing moods of fortune. I received then and have since been receiving a great number of telegrams and messages from all kinds of people and from all countries of the earth. One gentleman invited me to shoot with him in Central Asia. Another favoured me with a poem which he had written in my honour, and desired me to have it set to music and published. A third—an American—wanted me to plan a raid into Transvaal territory along the Delagoa Bay line to arm the prisoners and seize the President. Five Liberal Electors of the borough of Oldham wrote to say that they would give me their votes on a future occasion 'irrespective of politics.' Young ladies sent me woollen comforters. Old ladies forwarded their photographs; and hundreds of people wrote kind letters, many of which in the stir of events I have not yet been able to answer.

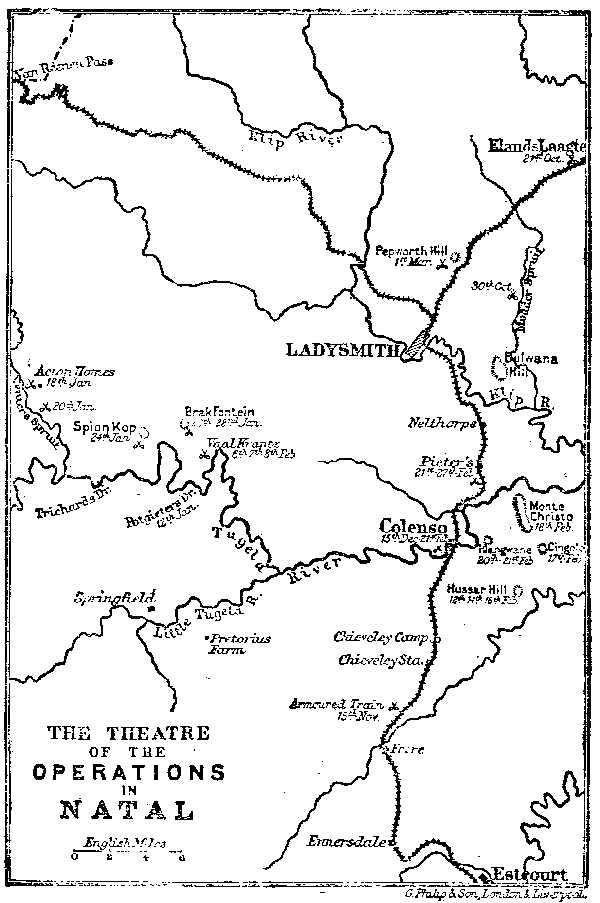

THE THEATRE OF THE OPERATIONS IN NATAL

The correspondence varied vastly in tone as well as in character, and I cannot help quoting a couple of telegrams as specimens. The first was from a worthy gentleman who, besides being a substantial farmer, is also a member of the Natal Parliament. He wrote: 'My heartiest congratulations on your wonderful and glorious deeds, which will send such a thrill of pride and enthusiasm through Great Britain and the United States of America, that the Anglo-Saxon race will be irresistible.'

The intention of the other, although his message was shorter, was equally plain.

'London, December 30th.—Best friends here hope you won't go making further ass of yourself.—M'NEILL.'

This shows, I think, how widely human judgment may differ even in regard to ascertained facts.

I found time to visit the hospitals—long barracks which before the war were full of healthy men, and are now crammed with sick and wounded. Everything seemed beautifully arranged, and what money could buy and care provide was at the service of those who had sustained hurt in the public contention. But for all that I left with a feeling of relief. Grim sights and grimmer suggestions were at every corner. Beneath a verandah a dozen wounded officers, profusely swathed in bandages, clustered in a silent brooding group. Nurses waited quietly by shut doors that none might disturb more serious cases. Doctors hurried with solemn faces from one building to another. Here and there men pushed stretchers on rubber-tyred wheels about the paths, stretchers on which motionless forms lay shrouded in blankets. One, concerning whom I asked, had just had part of his skull trepanned: another had suffered amputation. And all this pruning and patching up of broken men to win them a few more years of crippled life caught one's throat like the penetrating smell of the iodoform. Nor was I sorry to hasten away by the night mail northwards to the camps. It was still dark as we passed Estcourt, but morning had broken when the train reached Frere, and I got out and walked along the line inquiring for my tent, and found it pitched by the side of the very same cutting down which I had fled for my life from the Boer marksmen, and only fifty yards from the spot on which I had surrendered myself prisoner. So after much trouble and adventure I came safely home again to the wars. Six weeks had passed since the armoured train had been destroyed. Many changes had taken place. The hills which I had last seen black with the figures of the Boer riflemen were crowned with British pickets. The valley in which we had lain exposed to their artillery fire was crowded with the white tents of a numerous army. In the hollows and on the middle slopes canvas villages gleamed like patches of snowdrops. The iron bridge across the Blue Krantz River lay in a tangle of crimson-painted wreckage across the bottom of the ravine, and the railway ran over an unpretentious but substantial wooden structure. All along the line near the station fresh sidings had been built, and many trains concerned in the business of supply occupied them. When I had last looked on the landscape it meant fierce and overpowering danger, with the enemy on all sides. Now I was in the midst of a friendly host. But though much was altered some things remained the same. The Boers still held Colenso. Their forces still occupied the free soil of Natal. It was true that thousands of troops had arrived to make all efforts to change the situation. It was true that the British Army had even advanced ten miles. But Ladysmith was still locked in the strong grip of the invader, and as I listened I heard the distant booming of the same bombardment which I had heard two months before, and which all the time I was wandering had been remorselessly maintained and patiently borne.

Looking backward over the events of the last two months, it is impossible not to admire the Boer strategy. From the beginning they have aimed at two main objects: to exclude the war from their own territories, and to confine it to rocky and broken regions suited to their tactics. Up to the present time they have been entirely successful. Though the line of advance northwards through the Free State lay through flat open country, and they could spare few men to guard it, no British force has assailed this weak point. The 'farmers' have selected their own ground and compelled the generals to fight them on it. No part of the earth's surface is better adapted to Boer tactics than Northern Natal, yet observe how we have been gradually but steadily drawn into it, until the mountains have swallowed up the greater part of the whole Army Corps. By degrees we have learned the power of our adversary. Before the war began men said: 'Let them come into Natal and attack us if they dare. They would go back quicker than they would come.' So the Boers came and fierce fighting took place, but it was the British who retired. Then it was said: 'Never mind. The forces were not concentrated. Now that all the Natal Field Force is massed at Ladysmith, there will be no mistake.' But still, in spite of Elandslaagte, concerning which the President remarked: 'The foolhardy shall be punished,' the Dutch advance continued. The concentrated Ladysmith force, twenty squadrons, six batteries, and eleven battalions, sallied out to meet them. The Staff said: 'By to-morrow night there will not be a Boer within twenty miles of Ladysmith.' But by the evening of October 30 the whole of Sir George White's command had been flung back into the town with three hundred men killed and wounded, and nearly a thousand prisoners. Then every one said: 'But now we have touched bottom. The Ladysmith position is the ne plus ultra. So far they have gone; but no further!' Then it appeared that the Boers were reaching out round the flanks. What was their design? To blockade Ladysmith? Ridiculous and impossible! However, send a battalion to Colenso to keep the communications open, and make assurance doubly sure. So the Dublin Fusiliers were railed southwards, and entrenched themselves at Colenso. Two days later the Boers cut the railway south of Ladysmith at Pieters, shelled the small garrison out of Colenso, shut and locked the gate on the Ladysmith force, and established themselves in the almost impregnable positions north of the Tugela. Still there was no realisation of the meaning of the investment. It would last a week, they said, and all the clever correspondents laughed at the veteran Bennet Burleigh for his hurry to get south before the door was shut. Only a week of isolation! Two months have passed. But all the time we have said: 'Never mind; wait till our army comes. We will soon put a stop to the siege—for it soon became more than a blockade—of Ladysmith.'

Then the army began to come. Its commander, knowing the disadvantageous nature of the country, would have preferred to strike northwards through the Free State and relieve Ladysmith at Bloemfontein. But the pressure from home was strong. First two brigades, then four, the artillery of two divisions, and a large mounted force were diverted from the Cape Colony and drawn into Natal. Finally, Sir Redvers Buller had to follow the bulk of his army. Then the action of Colenso was fought, and in that unsatisfactory engagement the British leaders learned that the blockade of Ladysmith was no unstable curtain that could be brushed aside, but a solid wall. Another division is hurried to the mountains, battery follows battery, until at the present moment the South Natal Field Force numbers two cavalry and six infantry brigades, and nearly sixty guns. It is with this force that we hope to break through the lines of Boers who surround Ladysmith. The army is numerous, powerful, and high-spirited. But the task before it is one which no man can regard without serious misgivings.

Whoever selected Ladysmith as a military centre must sleep uneasily at nights. I remember hearing the question of a possible war with the Boers discussed by several officers of high rank. The general impression was that Ladysmith was a tremendous strategic position, which dominated the lines of approach both into the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, whereas of course it does nothing of the sort. The fact that it stands at the junction of the railways may have encouraged the belief, but both lines of advance are barred by a broken and tangled country abounding in positions of extraordinary strength. Tactically Ladysmith may be strongly defensible, politically it has become invested with much importance, but for strategic purposes it is absolutely worthless. It is worse. It is a regular trap. The town and cantonment stand in a huge circle of hills which enclasp it on all sides like the arms of a giant, and though so great is the circle that only guns of the heavier class can reach the town from the heights, once an enemy has established himself on these heights it is beyond the power of the garrison to dislodge him, or perhaps even to break out. Not only do the surrounding hills keep the garrison in, but they also form a formidable barrier to the advance of a relieving force. Thus it is that the ten thousand troops in Ladysmith are at this moment actually an encumbrance. To extricate them—I write advisedly, to endeavour to extricate them—brigades and divisions must be diverted from all the other easy lines of advance, and Sir Redvers Buller, who had always deprecated any attempt to hold Natal north of the Tugela, is compelled to attack the enemy on their own terms and their own ground.

What are those terms? The northern side of the Tugela River at nearly every point commands the southern bank. Ranges of high hills strewn with boulders and dotted with trees rise abruptly from the water, forming a mighty rampart for the enemy. Before this the river, a broad torrent with few and narrow fords and often precipitous banks, flows rapidly—a great moat. And before the river again, on our side stretches a smooth, undulating, grassy country—a regular glacis. To defend the rampart and sweep the glacis are gathered, according to my information derived in Pretoria, twelve thousand, according to the Intelligence Branch fifteen thousand, of the best riflemen in the world armed with beautiful magazine rifles, supplied with an inexhaustible store of ammunition, and supported by fifteen or twenty excellent quick-firing guns, all artfully entrenched and concealed. The drifts of the river across which our columns must force their way are all surrounded with trenches and rifle pits, from which a converging fire may be directed, and the actual bottom of the river is doubtless obstructed by entanglements of barbed wire and other devices. But when all these difficulties have been overcome the task is by no means finished. Nearly twenty miles of broken country, ridge rising beyond ridge, kopje above kopje, all probably already prepared for defence, intervene between the relieving army and the besieged garrison.

Such is the situation, and so serious are the dangers and difficulties that I have heard it said in the camp that on strict military grounds Ladysmith should be left to its fate; that a division should remain to hold this fine open country south of the Tugela and protect Natal; and that the rest should be hurried off to the true line of advance into the Free State from the south. Though I recognise all this, and do not deny its force, I rejoice that what is perhaps a strategically unwise decision has been taken. It is not possible to abandon a brave garrison without striking a blow to rescue them. The attempt will cost several thousand lives; and may even fail; but it must be made on the grounds of honour, if not on those of policy.

We are going to try almost immediately, for there is no time to be lost. 'The sands,' to quote Mr. Chamberlain on another subject, 'are running down in the glass.' Ladysmith has stood two months' siege and bombardment. Food and ammunition stores are dwindling. Disease is daily increasing. The strain on the garrison has been, in spite of their pluck and stamina, a severe one. How long can they hold out? It is difficult to say precisely, because after the ordinary rations are exhausted determined men will eat horses and rats and beetles, and such like odds and ends, and so continue the defence. But another month must be the limit of their endurance, and then if no help comes Sir George White will have to fire off all his ammunition, blow up his heavy guns, burn waggons and equipment, and sally out with his whole force in a fierce endeavour to escape southwards. Perhaps half the garrison might succeed in reaching our lines, but the rest, less the killed and wounded, would be sent to occupy the new camp at Waterfall, which has been already laid out—such is the intelligent anticipation of the enemy—for their accommodation. So we are going to try to force the Tugela within the week, and I dare say my next letter will give you some account of our fortunes.

Meanwhile all is very quiet in the camps. From Chieveley, where there are two brigades of infantry, a thousand horse of sorts, including the 13th Hussars, and a dozen naval guns, it is quite possible to see the Boer positions, and the outposts live within range of each other's rifles. Yesterday I rode out to watch the evening bombardment which we make on their entrenchments with the naval 4.7-inch guns. From the low hill on which the battery is established the whole scene is laid bare. The Boer lines run in a great crescent along the hills. Tier above tier of trenches have been scored along their sides, and the brown streaks run across the grass of the open country south of the river. After tea in the captain's cabin—I should say tent—Commander Limpus of the 'Terrible' kindly invited me to look through the telescope and mark the fall of the shots.