|

|

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

|

|

|

Thus far we have been looking at the Progressivist Era largely in terms of its material quality, presented in terms of the vast material wealth that a number of Americans enjoyed, or the lack of that same wealth suffered by others, and the politics involved in trying to make such materialism work to the greater advantage of individuals, groups of individuals, and even the nation as a whole. We have looked at individuals whose energy made much of this possible, the captains of industry and finance (or "robber barons" if you were distressed at how poorly this rising wealth was distributed more broadly among the American population) and the inventors and technical innovators whose ideas kept the Progressivist Era moving ever forward to new and truly amazing material inventions and developments. The Age of Progress and the "Revolution of Rising Expectations."

But at this point we want to look more closely at the spirit of the times, the intellectual, moral and spiritual character of American culture, and the forces that shaped it. It is important to note that the very idea of wealth, or of poverty, is not itself an objective matter, like an automobile, a large or small house, the clothes someone wears, the humble or exotic nature of what is found on the dinner table, etc. Indeed, the very poor were actually better off materially than the middle classes of just a couple of centuries earlier, when the planet was less able to support a large human population. People of course still suffered from fatigue, hunger, disease, and just plain aging. But the profile of Westerners at the turn of the century demonstrated actually a vitality among vast numbers that would have been unthinkable just generations earlier. Yet poverty was there, bitter poverty for some, especially for those (mostly in America's fast-rising cities and industrial towns) whose lives contrasted so sharply with the lives of the very, very wealthy, who benefitted awesomely from the labors of these poor souls. Yet the poor souls were actually doing much better materially than their medieval counterparts. But expectations were there nonetheless that justice was not being well served by the way America's vast wealth was being distributed. Certainly that idea formed much of the drive behind the Progressivist Movement. If the gap between rich and poor (as it has always been through the ages) had remained largely unchanged, little would have been said about the matter. It would have been accepted as the normal scheme of things (as it was for centuries). But things were changing rapidly, and with them the expectations of the benefits, the fruits of change. And those expectations, emotional and intellectual, were the reality that people actually responded to. And they were rising as fast or faster than the actual material growth of the American economy and technology. With time the simplest of Americans would be drawn into the world of the new gadgets and lifestyle possibilities, because such fast-developing wealth needed the American people themselves (what ultimately we would identify as the consumer) to absorb the end products of the economic system. Henry Ford understood this principle very well, and got very rich from it. But America's reality at the turn of the century was not really in just interesting material statistics, but in the fact that America was going through a "Revolution of Rising Expectations." And those expectations were the reality that Americans responded to. So at this point we turn to the all-important question: what exactly were those expectations? What was it exactly that Americans were thinking concerning their situations, their lives? The mechanics of social thinking

People themselves are actually not very innovative thinkers, but borrow thought from larger society. Individuals have personalities of their own, of course. But even more importantly they develop social personalities, a sense of personhood drawn from the cultural themes around them, themes that others generate for them individually (opinion leaders) and collectively, out of a commonly-perceived social experience they find themselves in. In other words, people mostly follow the crowd of one kind or another. And what they do, how they act, how they react, is shaped not so much by their own personal reasoning as much as by the reasoning of the social group they identify themselves with – or actually groups, some cooperating to give even more cohesion and strength to a person’s social identity, or on the other hand clashing, causing much personal confusion and frustration. So again, what were Americans thinking at this time? How were they redesigning their personal universe? Something big was going on – because all this material change was stirring new cultural ideas that challenged Americans to rethink their world. Europe's lead in the emerging "Post Christian" culture

One more point. America itself was not doing this in isolation, but was itself participating (mostly willingly) in a larger rethink of all of Western Civilization. This civilization used to be called "Christian Civilization." But although people still used that language in describing a desirable Christian world, a larger Christian moral code, a set of Christian social goals, the reality was that Christianity was not any single social-political idea – as the violent Protestant-Catholic Wars of Religion of the early-mid 1600s clearly demonstrated. In any case, new ideas were on the rise within this Christian West that had no connection with the idea of the sovereign rule of God or the saving power of Jesus's lordship over the world. Something else in the West was fast replacing Christian culture, a new culture identified by various labels: Materialism, Empiricism, Darwinism, Secularism, Humanism, Socialism, etc., all of which developed from this rising sense of man's own powers to conquer and reshape the world by his own designs, his own logic, his own powers, his own ability to see his human programs put into place to make this world a much, much better place. All of this mental energy was thus serving in different ways to give Western Civilization a new and very aggressive character. It was all very heady stuff. Just in looking around at all the material bounty that came with this new-think, it is not surprising how very compelling this new culture was. Christianity, with its call for humility in approaching life and its emphasis in trusting God alone to get things right, just did not appear to be the sure and certain formula for acquiring the offerings of this new world of material bounty. And thus people's minds and hearts were fast shifting to this exciting new world of what could be summed up basically as Secular Humanism. In this development, Europe was way ahead of America. But America was learning quickly. America had its own new ideas about life. But by and large Americans found themselves greatly attracted to the high level of social thought coming from Europe. In fact it was considered to be the height of sophistication to go off to Europe to study (the reverse was hardly the case yet!). Indeed, in the realm of higher thought, America mostly found itself simply responding to European developments that were well underway across the Atlantic. And that would even take America right

into the Great War (World War One, 1914-1918) which America long

debated before making the fateful decision to jump into the event.

|

|

|

The very ancient roots of the central problem arising with the adulation (even worship) of Human Reason The use of human reason rather than reliance on divine guidance is not a new issue on this planet. It certainly did not arrive for the first time with Europe's step into the Modern Age, considered by historians to have started somewhere around the mid-1600s, with the end of the Wars of Religion. The very ancient Judeo-Christian Bible begins its narration with this very issue – immediately after the story of divine creation. The narration centers on man's first temptation: to go his own way rather than to go with God. That is the essence of the story of the Garden of Eden when God had forbidden Adam and Eve to eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. He did not explain why, because they were still obedient to God rather than deciding themselves what was good and what was evil. However, the Tempter in the form of a serpent soon intervened in the story to put the thought in the minds of this primal couple, that knowing on their own what was good and what was evil would make them like God. That was (and still is) quite a temptation, one they could not or anyway would not resist. And so, they ate of the forbidden fruit, and troubles began immediately. Western Civilization continues to wrestle with this same issue

It's a great story, absolutely ageless in its wisdom, as Europe was already discovering. And if they had not learned about the Truth of the narrative in observing the events of the Wars of Religion (also known as the Thirty Years' War of 1618-1648) or the French Revolution at the end of the 1700s, they were about to have the issue put squarely in front of them again in the form of the Great War (World War One, 1914-1918), which, unknown to them, was about to break out in seemingly unprecedented fury. But that part of the story belongs to our next chapter. But in any case, let's at this point take our story of Western Civilization's effort to make sense of this newly emerging world, all the way back to Europe during the times of the European Enlightenment, beginning in the later 1600s, truly blossoming in the 1700s, and challenging in so many different ways the 1800s. Looking at the birth and development of these modern trends of social thought and action should help us not only to understand how we got this way, but also the difficulties we will have if we do not learn from the past. We have already discussed Locke and Rousseau in some detail. But they were children of the European Enlightenment, not its founders. The Puritans were actually major contributors to this emerging "Enlightenment" The Puritans were actually major contributors to this emerging "Enlightenment." This "Age of Enlightenment" had its origins in the early 1600s, with the rise of "natural philosophy" – something we today term as "science." Very active in this matter of the "philosophy of nature" were the English Puritans, led by such intellectuals as Francis Bacon, who at the turn of the 1600s celebrated the new discoveries of the workings of the natural world … seeing the hand of an incredibly awesome God in the newly discovered grand designs of nature. Bacon's "science" was treated as almost an act of worship ... as it would be for so many of the other Puritans – who, for the same reason (seeing their natural philosophy as a witness to the glory of God), took the lead in England's scientific revolution that broke forth in the 1600s. And much the same was the case for the Puritans' Calvinist cousins over in the Netherlands! Descartes (early 1600s) challenges Christian Truth with a new reliance on Pure Reason

This was not just some philosopher's idle question. Descartes was living at a time in which the wars between Catholics and Protestants and between rising monarchs in different parts of Europe were constant and having a deadly effect on European society. Each of the contenders justified his brutal violence on the basis of one or another truth-claim. So Descartes took up the challenge of trying to lay out a basis by which the contenders could pursue these truth-claims logically, rather than violently (presuming that these contenders were indeed all that interested in Truth rather than just domination). Descartes observed that the world around us operated purely mechanically (or mathematically), and that if we disciplined our minds to work in the same way (rationally or mathematically) we could actually close that gap between our minds and the surrounding world. There was no need for inspiration, no need to rely on tradition or the conventional teachings of society. Man was fully capable of arriving at all truths – even able to prove the existence of God – simply through the exercise of precise human reason. With that Cartesian challenge, the Age of Reason was off and running.

|

|

|

Newton – Leibniz – Locke

Three individuals stand out in particular in the follow-up (the later 1600s) to Descartes' birth of the Age of Reason: the two Englishmen Isaac Newton and John Locke and the German Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz and Newton were both brilliant mathematicians. Both seemed to have discovered calculus at about the same time (around 1670). Leibniz tended to follow more closely the lead of Descartes and other Rationalists on the European continent in believing that pure reason, built simply on logical principles arrived at through clear thought, could design a perfect world – and was optimistic that such was soon possible. Newton tended more to the empirical side (typical of the British), believing that nothing could be considered true until it had been observed to actually work in the real world. But he was also something of a Christian mystic, which in general the continental school of Rationalism rejected completely. We have already met Locke (a friend of Newton's) who too believed in the power of human reason to solve life's various problems, whatever they might be. Locke, like Newton, was also a highly empirical philosopher who stressed the importance of putting our ideas to the test of observing their success (or failure) in the actual world of people and things. We also know that Locke was very much a social philosopher. But he was also a student of human psychology, able to put the two worlds of the individual and society together in a rational order. His understanding was that human thought is importantly a collective matter, shaped by the thinking of the larger social world and the particular experiences that this social world was facing and how a society interpreted those experiences. But again, his belief was that this social world could be – must be – improved through the careful thinking through of life's processes, in order to bring life closer to perfection. Locke and his writings would go on to influence deeply the philosophy of most of the social philosophers of the 1700s (including importantly Thomas Jefferson).

|

|

|

Rousseau and early Romanticism

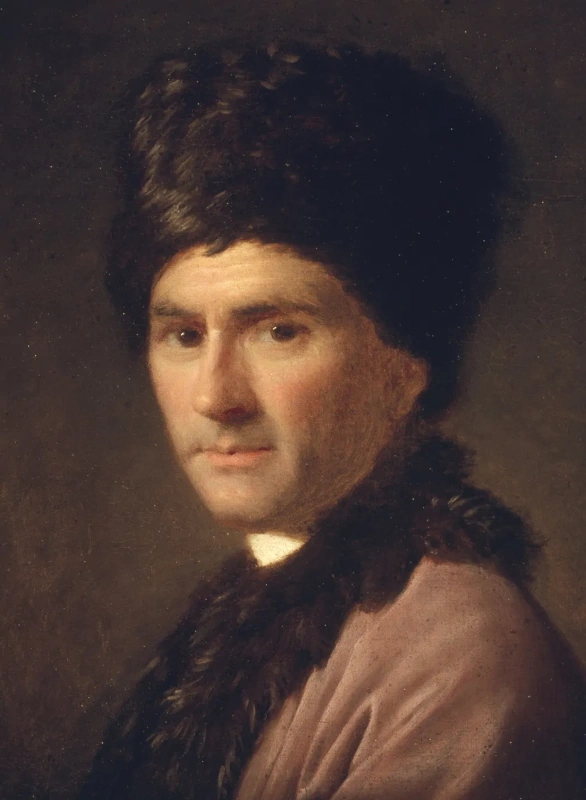

Rousseau claimed that originally man lived in some kind of simple natural state of harmony, without laws or government. But life had evolved over time into a more complex form – civilization – requiring as it developed greater mutual dependence among men for the orderly working of society, and thus also a more complex system of moral instruction or law to guide this more complex society. Man accordingly had to give up his total personal sovereignty to come under the protection and nurture of more complex society. But he was giving it up not to some ruling individual but to the larger idea of the society as a whole, the general will – in particular its laws, which were the clearest expression of a people's general will. The laws, not any particular individuals, were the locus of sovereignty in the truly good society. Unfortunately, ignorance of this good had clouded people's political understanding, causing them to slip into all forms of political tyranny (absolute rule over society by particular individuals such as kings and dukes, which was the general pattern of his day). Rousseau's hope was to open men's eyes to the understanding of what was truly right and good about society, that such knowledge would free men to usher in a good or utopian society that was truly the right of everyone to enjoy, not just the privileged few. All the superfluous fluff of decadent civilization (in particular French civilization as it was viewed in his own time) would be simply swept away by the opening of the eyes of the people to the Truth. With the Ancien Régime (the Old Order comprised of the officers of the king and church that dominated all European society in the 1700s) thus swept away, society would be free to create or contract a social system as simple and basic as possible, a social system directed by a set of basic laws that restored to man his fundamental liberties, allowing him to live as close to the original state of nature as possible. The French were strongly impacted by Rousseau's theories – as have been many revolutionary-minded secular philosophers since Rousseau (as well as modern "hippies" trying to go back to nature in simple communal living). Rousseau's vision of primitive society even found its way into the polite social gatherings or salons of Europe's ruling classes and their intellectual tutors. Thus it was that the future queen Marie Antoinette used to love to play in the Versailles palace gardens (with fellow maidens at the French court) at being a peasant girl herding her sheep. It was all so quaint, so romantic. The French monarchy was sick, very sick. Reform was needed. But by Rousseau's logic, that reform was going to have to be extensive for the good society to result. The Old Order was going to have to be set aside in its entirety in order to make way for the new. Thus with Rousseau's encouragement, the French political mood was becoming increasingly revolutionary as the political debate in the late 1700s intensified in France. |

| French-speaking Genevan (Swiss) philosopher, author of Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract, explaining his views on the relationship between the individual and society. |

|

|

The further reaction to Europe's Rationalism

In the American colonies in the mid-1700s the Western Enlightenment was answered by the mysteries of the Great Awakening – led by such figures as Edwards and Whitefield, and by the broad popular response of the common people to that dynamic. While continental Europe in general was by-passed in that event (the British, however, certainly had their own version of the Great Awakening), nonetheless as the 1700s moved along, something of a strong reaction to Rationalism also set in among some of the Continental European as well as British philosophers and scholars, something however that had very little to do with going back to Christian basics. That non-Christian reaction to Rationalism would take very different forms – tending to Empiricism in Britain and Romanticism in Continental Europe (though varieties of Empiricism and Romanticism could be found in both locations). British Empiricism

To begin with, the British were of a more practical mindset in their love of hands-on experimentation than their continental cousins, who loved to sit at their desks or gather at polite salons to indulge themselves in the world of pure thought. During the Enlightenment the British were too busy inventing new material technologies – and developing the industries to put those technologies to practical use – to be wasting time speculating about hypothetical realities. They were all, by nature, Empiricists. David Hume promotes Empiricism

Likewise, Hume was most unimpressed by the great intellectual "spins" that philosophers wove around hypothetical behavior in building their great systems of thought. For Hume reality was in the doing, not in the hypothesizing about life. Widely studied, Hume became well-known in his time for his skepticism about speculations about God, or great systems of religious Truth, or the validity of "objective" ethical systems, even the claims of science to have established an explanation of all life in terms of cause and effect. All this was to Hume mere intellectual humbuggery. Hume's impact lived long after him. In fact it was Hume that awakened the great German philosopher Kant from his "intellectual slumber" (as Kant himself put it) and caused Kant to undertake the task of responding to the challenge that Hume had issued to those who would claim to understand human nature, even life itself. Adam Smith explains capitalism

Building on this attitude was the fellow Scot, Adam Smith, who in his Wealth of Nations (1776) wrote a compelling explanation of how simply letting the competitive marketplace bring forward the material blessings of life – and the pricing involved for such wealth – would also naturally bring forth human progress. He was much opposed to the idea of forcing on society the designs of utopian social planners, who would soon enough make a mess of things with their well-reasoned schemes. In fact, Smith was strongly opposed to any kind of "intervention" into this market mechanism by the government or any other outside societal institution. To Smith (and all capitalist philosophers since then) this independence of commercial action was the key doctrine of Capitalist philosophy. But at the same time, Smith was highly opposed to market insiders getting together to conspire to set prices through a withholding of goods or services to create an artificial scarcity. He was thus opposed to cartels, monopolies, and unions, of any variety. He also considered the danger of rapid population growth distorting the labor market and driving prices down to subsistence levels. But he felt that economic growth of the whole industrial sector would constantly increase the demand for labor and thus prevent such cruelties from occurring.

|

|

|

Kant attempts a compromise between British Empiricism and French Rationalism

Kant agreed with Hume's empiricism, namely that essential to human knowledge is our sense experience – the experience of the seeing, feeling, hearing, etc. of real material objects around us. But he also agreed with the continental Rationalists (most notably Leibniz, whose writings also were a major influence on Kant) that knowledge is also a matter of the exercise of human reason, in particular the use of innate human ideas ("categories") which we are born with and which help us to organize this empirical information. Thus Kant saw himself as closing the intellectual gap between the British Empiricists and the Continental Rationalists. Kant also saw himself as answering Hume's skepticism about ever knowing with any degree of certainty the Truth of transcendent ideas, such as moral laws or ethical principles (not to mention the idea of Heaven itself). In Kant's Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788), he proposed a new moral/ethical "categorical imperative," one that did not require the existence of God for its validity. It involved an ingenious piece of moral logic: we ought to act in such a way that our act could become accepted as a universal principle of behavior. If it were not able to attain such a universal validity (because, for instance, of an internal contradiction in logic) then that action, by "practical reason," was obviously not to be pursued. Taking this logic of "practical reason" a step further, he turned to the issue of the existence of God. He agreed with Hume that no rational argument could be given for God's existence – that is, "pure reason" could not build a case for God's existence. But "practical reason" could. Pursuing a traditional line of reason that went back at least as far as Ockham in the early 1300s, Kant claimed that human reason cannot establish the "fact" of God. But in observing the moral instincts of people we can see (through the eyes of faith) that there is some kind of source beyond the mere human will itself that directs life. That higher moral grounding is by definition God. Thus God exists. (This kind of theological reasoning did not impress the Prussian government, which censured his work). Finally, so impressed was Kant that we humans could live in accordance with such higher moral imperatives that in his Perpetual Peace (1795) he laid out a vision for a new world order. Here (despite the Reign of Terror going on in France) begins the utopian idealism that will absorb the thoughts and aspirations of intellectuals for generations to come.

|

|

|

Of course Rationalism was by no means dethroned by Rousseau's Romantic reaction or the challenge of British Empiricism, because it was pure Rationalism that drove French intellectuals (and Paris mobs) to their violent behavior during the French Revolution, a revolution that soon produced horrors on the scale of the Religious Wars of the 1600s that had first inspired Rationalism. During the violent revolution that broke out in 1789, absolute Reason brought forward powerful people who became also absolute in their authority, and thus highly susceptible to very sophisticated self-deception as they murdered people by the thousands in the name of Reason. What these Rationalists failed to see was how easily reason, in the face of the serious challenge of ruling a very diverse people, could be so easily twisted to serve merely their own narrower self-interests,1 rather than the dreamy goal of serving all the people according to some kind of higher interest they claimed they were pursuing. What these utopian Rationalists had naively come up against was the complex issue called reality, something of which in their lofty world of aristocratic salons they knew virtually nothing. Reactions to the French Revolution

With the exception of Jefferson, who while living in France just prior to the 1789 Revolution fell entirely in love with French Rationalism, Americans in general took the same attitude as the (Irish) Edmund Burke, who expressed eloquently the horror that all of Britain felt about the very barbaric results of the noble effort of the French people trying to be entirely rational. Burke pointed out (like Hume) that long-established tradition served the people well and should only be reformed carefully as necessary, not overthrown. Like the French, the Americans at the time were birthing a new Republic. But unlike the French, the American Republic was built cautiously on a very limited or restricted basis on political traditions and practices already well-established in the colonies over the previous century and a half. Americans were not setting up a new government built on untested new principles dreamed up by social planners, like the French were attempting. And (as we have already seen) the results consequently were quite different from America to France.  The Napoleonic challenge The Napoleonic challenge

Eventually (1799) France was rescued by the military dictator Napoleon from the murderous folly of the French Revolution's "Reign of Terror" (1792-1795) and the political chaos that followed it. Napoleon retained technical features of

the Revolution and even improved on them, for instance, supporting the

metric system and rationalizing regional government through a new

bureaucratic system which replaced the chaotic array of multitudes of

local feudal domains each with their own laws, standards and social

interests. Pierre Simon de Laplace gives Rationalism a new lease on life

This idea of a small residual divine intervention was not a satisfying concept to the French Rationalist Laplace. He understood the universe to be totally operative under the impersonal, mechanical laws of nature. So in 1773 he set out to give full mathematical explanation to the motions of the heavens – in such a way that there would be no more need to call in God as the residual part of the equation. This he successfully completed years later an unprecedentedly in-depth mathematical calculation of the eccentricities in the planetary orbits, taking into account their gravitation attraction to each other as well as to the sun as they moved through their respective orbits. This work was eventually compiled into the five-volume study: Celestial Mechanics (1799-1825.) And it earned him a place in the prestigious French Academy of Sciences. It also removed the idea of God further (if not completely) from the mechanistic cosmology that had been unfolding over the previous century. Not even Deism could stand up to this assault. Indeed, the story goes that when Laplace presented a copy of his work to Napoleon, the latter uttered a concern that Laplace had made no mention in his work of the divine "Originator" of this marvelous system. To this, Laplace replied quite simply: "I had no need for that hypothesis!" 1But

isn’t this what we pay lawyers to do for us: use powerful "Reason" on

our own behalf? Isn’t this what both sides are doing in a civil

or criminal case, with its opposing lawyers each skillfully presenting

rational arguments on behalf of their particular clients before a judge

or jury? Even mobsters have well-paid lawyers to defend

rationally or "justify" their behavior in court.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges