6. THE SHAPING OF A NATION

THE "ERA OF GOOD FEELINGS"

CONTENTS

James Monroe (the fourth James Monroe (the fourth

Virginian president!) 1817-1825

The economic Panic of 1819-1821 The economic Panic of 1819-1821

Florida Florida

The Missouri Compromise (1820) The Missouri Compromise (1820)

The "Monroe Doctrine" (1823) The "Monroe Doctrine" (1823)

Monroe's final years as president Monroe's final years as president

(1823-1825)

John Quincy Adams – President John Quincy Adams – President

(1825-1829)

The tough question of Indian vs. The tough question of Indian vs.

Anglo land rights

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 210-220.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1810s |

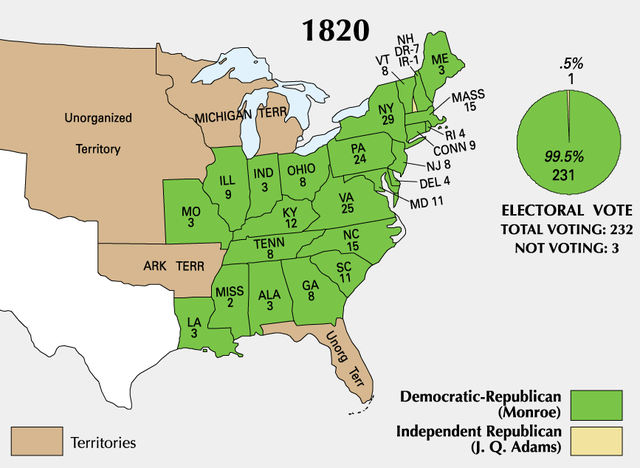

Something of an "Era of Good Feelings" supposedly sets in on-postwar America

1816 The Second Bank of the United States (BUS) is formed (the charter of the first one was not renewed in 1811)

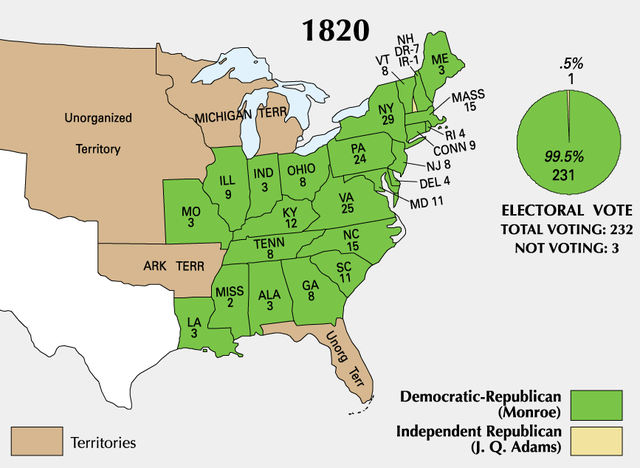

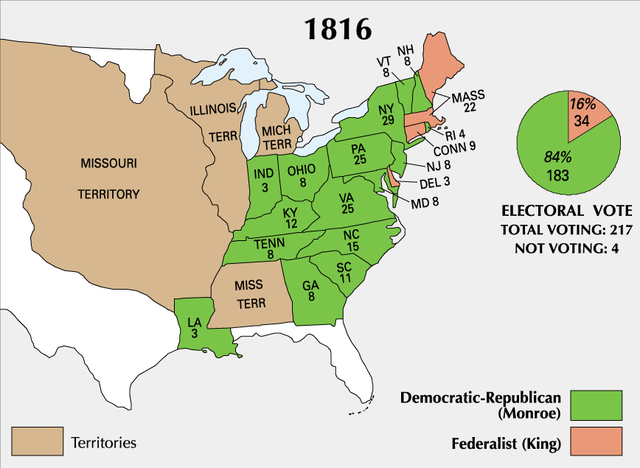

James Monroe scores a landslide victory for the presidency over the Federalist candidate; he is a congenial man,

hoping to promote national unity and end the political partisanship characteristic of the Federalist-Republican feuding; but he is also

too accommodating to be able to curb the feuds that grow within his cabinet

1818 Jackson marches an army into Spanish Florida, ostensibly to break Seminole Indian power ... and then overruns Spanish

positions (an act of war with no Congressional authorization)

1819 The stunned Spanish sign the Adams-Otis Treaty acknowledging the loss of Florida (and also any claims to the Pacific

Northwest) ... they are paid $5 million in compensation for Florida

McCulloch v. Maryland denies the right of the states to tax federal agencies (the Maryland branch of the BUS); Dartmouth College v. Woodward confirms the sanctity of all contracts

A tight money policy by the BUS has thrown the country into deep recession ... at the same time that cotton from India emerges as a new challenge to the South's cotton

production

Ultimately Federal spending and farmer's overborrowing produce a huge speculative crash

|

| 1820s |

A restless spirit also infects the nation during this time period

1820s America is fast becoming an

industrial nation (agriculture, textiles, heavy industry) ... and within 20

years will equal or surpass British productivity in many

industrial areas

Americans head Southwest, towards New Mexico via the Santa Fe Trail

1820 Henry Clay proposes the "Missouri Compromise" setting a north-south boundary distinguishing the Slave and the

Free states ... determining which category new states will belong to in

entering the Union; this

"solution" to the problem merely highlights a deepening North-South

divide

1821 Cohens v. Virginia: Marshall declares that the Supreme Court has review powers over state courts

1823 Monroe announces to Congress his "Monroe Doctrine" dedicating America to the defense of the Latin American

Republics which had recently secured their independence from Spain (the English

were major silent partners in this policy, offering the necessary

military backup)

1824 Gibbons v. Ogden holds that only the federal government can regulate inter-state commerce

1825 John Adams' son John Quincy Adams becomes president ... and offers America four year of amazingly calm government

1828 The Baltimore and Ohio railroad is founded ... beginning a rush to build railroads that will continue unabated through the entire 1800s

|

JAMES MONROE (THE FOURTH VIRGINIA

PRESIDENT!)-(1817-1825) |

|

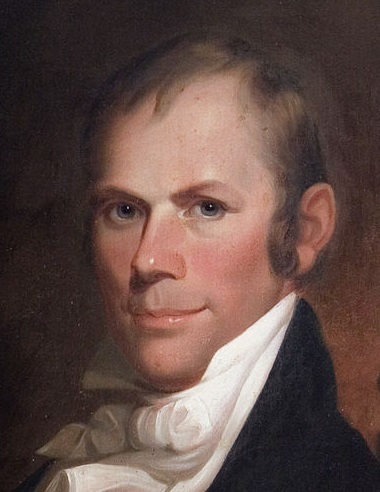

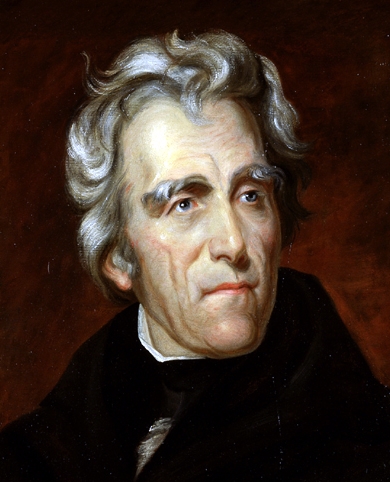

James Monroe (the fourth Virginian president: 1817-1825)

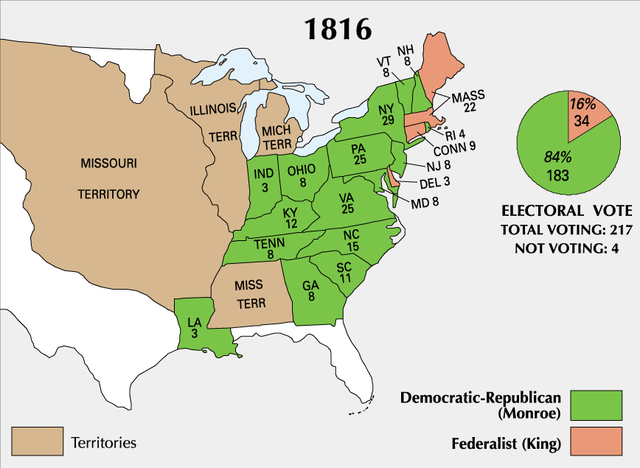

In

December of 1816 the electoral college gave a complete thrashing to the

dying Federalist Party when it elected the Jeffersonian Republican James

Monroe to the presidency by 183 votes in his favor, against only 34 votes

for the Federalist Rufus King of New York.

Monroe was not an exciting politician. But he more than made up for

his lack of charisma with his personal dedication to the young American

nation that he had served so well. He served in Washington's army and

took part in many of the famous battles of the War of Independence, rising

to the rank of colonel before he resigned his commission to study law

under Jefferson. He would follow in the footsteps of Jefferson, becoming

America's minister to France, then governor of Virginia. He then became

President Madison's secretary of state, and thus a natural choice of the

Republicans for the presidency when Madison indicated his intention to step

down from the presidency after two terms.

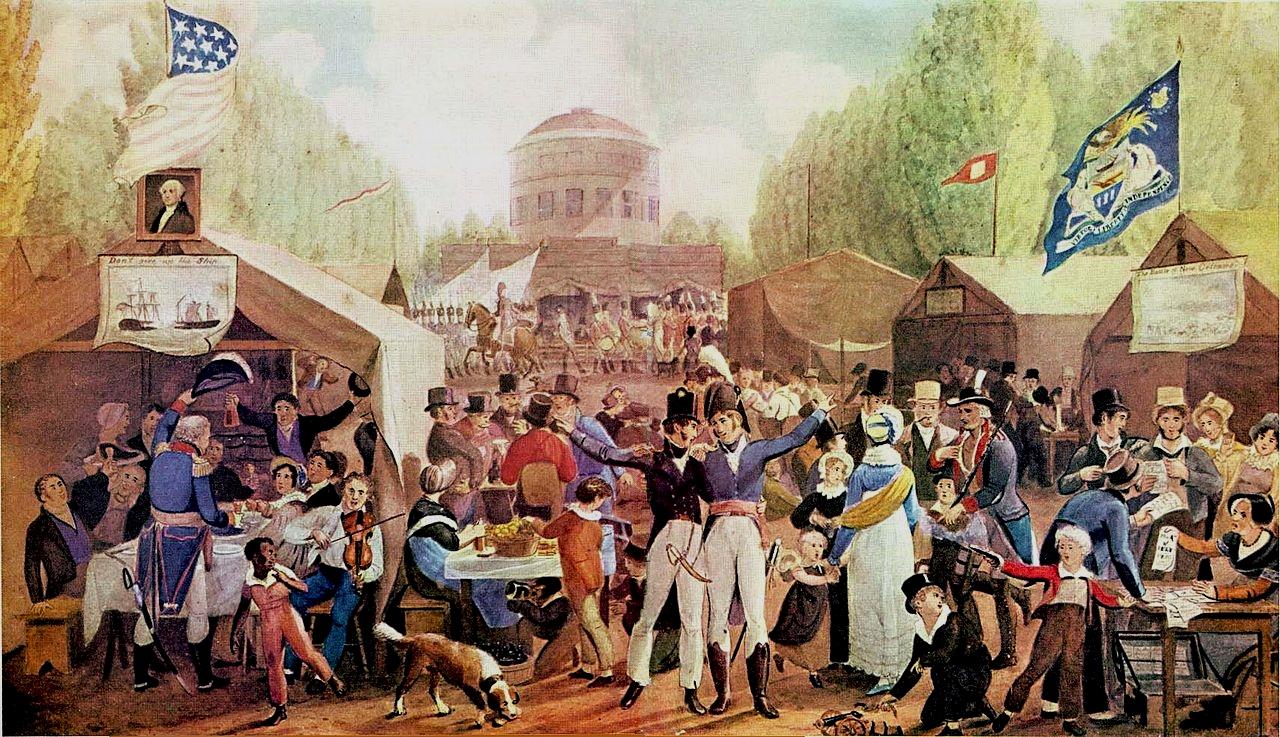

America relaxed greatly in finally finding peace with England and

France in 1815, producing a lively sense of optimism which in turn in 1817

prompted a Boston newspaper, the Columbian Centinel, to entitle the new

post-war period the "Era of Good Feelings." Yet there were a number of

problems still facing the country.

|

James Monroe

- the Fifth President of the United States – by John Vanderlyn (1816)

National

Portrait Gallery – Washington, D.C.

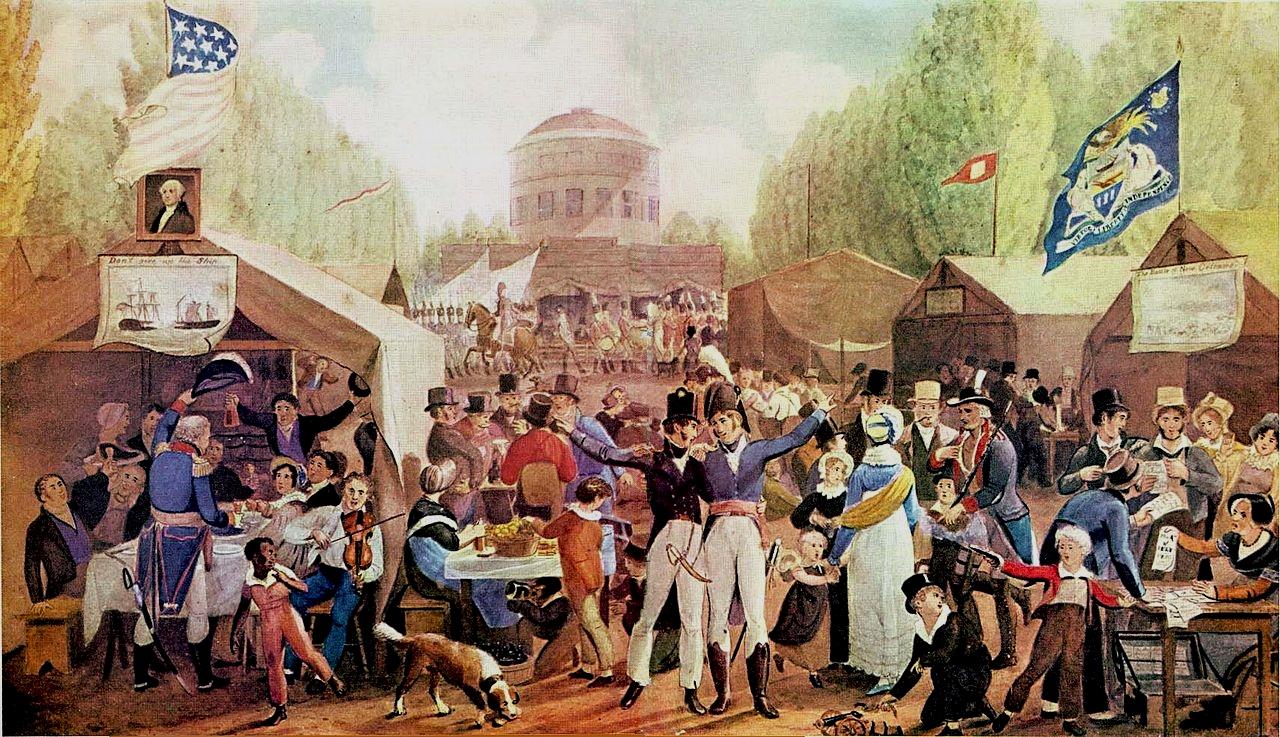

Again ... celebrating the 4th of July (1819) in Philadelphia during the days of the

"Era of Good Feelings"

THE

ECONOMIC PANIC OF 1819-1821 |

|

The biggest problem the nation faced at this point was the state of the

nation's economy. The war had thrown the government treasury into deep

debt, a debt financed largely

by the government's borrowing from a number of private banks. This

borrowing in turn flooded the economy with new bank notes, producing a

currency inflation that threatened the financial stability of the

country.

Furthermore, the private sector was in just as much

trouble. With the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, the demand in

Europe for American agricultural goods, which had produced much of the

prosperity of the Era of Good Feelings, dropped away rapidly (European

soldiers had returned to their farms, thus ending the demand for

American farm goods). The price of farm products faded away in America,

leaving farmers unable to pay the debts they had acquired in buying

more land to meet the former high European demand. Land prices also

fell as farmers scrambled to sell off some of the land they had

purchased.

Banks that held farmer's mortgages soon also found

themselves in trouble as well, the banks demanding from the farmers

cash payments, cash which the farmers simply did not have. The bankrupt

farmers being forced to turn their land titles over to the banks was no

help to the banks, as the land was now valued at much less than the

original loans the banks had extended to the farmers. Also, people now

began to make a run on potentially troubled banks, demanding specie

(gold or silver) for the bank notes issued previously by the banks. As

the banks had issued paper notes ten times the value of the metallic

specie they held in their vaults, they were simply forced to shut down.

By 1819 and 1820, banks, farms, and other businesses were closing down

everywhere.

Understanding the economic dynamic

This was the first major panic, like those that

would hit the country at regular intervals, such as in 1837, 1857,

1873, 1893, and 1907. The pattern of the 1817 panic was also very

similar to the one that developed within rural America just after World

War One (1919-1920) when American farmers and their banks found

themselves in exactly the same situation. And there were similar

elements in the situation during the 1930s Great Depression when

American manufacturers found that the market for their new consumer

goods was saturated, most Americans now possessing the radios, cars,

sewing machines, washing machines, etc., that had the industrial market

running so hot in the 1920s.

It is the very nature of venture capitalism to get

caught up in these wild swings of fortune, especially because of the

aggressive – and risk-taking – nature of capitalism itself. A

capitalist economic system is shaped very heavily by the personal

economic decisions that the individual members of society themselves

make. At the same time, the system is subject to unpredictable forces,

simply because there are so many forces at play in a free or open

national economy. But history has demonstrated over and over again that

it is better to let those mysterious factors play out than to try to

bring them under the mastery of some small group of enlightened

economists or social planners. Such Socialism, in trying to bring these

mysterious social and economic forces under human control, simply ends

up snuffing them out. Invariably Socialism brings into being the most

oppressive and impoverished of all economic systems.

Of course, some moderate amount of governmental

refereeing of the economic game played in a market open to all private

producers and consumers is wise. But the governing referee must never

start trying to play the game itself or the game will simply stall.

This would be, after all, just another version of Socialism.

Actually, in 1816, just prior to the outbreak of

the Panic, Congress had voted into existence the second Bank of the

United States in order to bring the economy under some kind of stricter

management. Eventually the financial discipline that the BUS imposed on

the nation (tightening the country's money supply) brought down the

inflation, and helped stabilize the value of the nation's currency. At

first this intervention merely deepened the crisis, leaving many

businesses, large and small, facing collapse when they could not repay

the cheap money they had borrowed earlier with the money now due on

their loans, money (especially silver and gold coinage) that was now

much more scarce and thus more expensive for them. Then when in early

1819 American cotton prices crashed as a result of the British purchase

of cotton from India, panic set in. But the BUS did not let up on its

tight money strategy, despite the country's economic reversal from

inflation to deflation.

Finally the economy settled down and began to

revive, though less from any activity of the BUS than from the

availability of new Mexican silver to back an expansion of America's

money supply in metallic specie.

But not surprisingly, as with the first BUS, the

second BUS would come under the intense dislike of America's vast

legion of farmers – who, as always, loved cheap money and inflation

since it allowed them to repay their mortgages and other operational

loans much more easily with cheaper or inflated dollars. Besides, to

their way of looking at things, the banking world was simply the tool

of wealthy exploiters operating out of the industrial East.

Thus sadly, the stumbling economy, and the

government's efforts to revive it, had undermined the spirit of

national unity produced by the war, and revived the old sectional

rivalries that divided the country.

These events would also split the Republican Party

into the New Republicans (in many ways similar in their economic and

political philosophy to the former Federalists) and the

Democratic-Republicans (closer to the original Jeffersonians).

These events would also bring the short-lived Era of Good Feelings to

an abrupt end.

|

A cartoon commenting on the economic Panic of 1819-1821

| The

Napoleonic Wars of 1800-1815, during which Spain had been torn between

French efforts at political control of their country and desperate

Spanish efforts to throw off the French grip, had left Spain greatly

exhausted. As a result, Spain proved to be powerless in its efforts to

head off independence movements among its Spanish colonies in America

(for example, Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina) which erupted during

this period. And where Spain continued after the war to hold on to some

kind of position in America, that hold was very weak. This certainly

was the case in Florida.

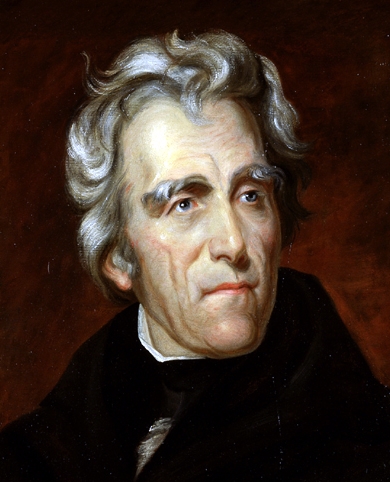

Seminole Indian raids from Spanish Florida into

Georgia and Alabama ultimately decided the fate of Florida. Because of

these raids, American Secretary of War John C. Calhoun in late 1817

ordered the hero of New Orleans (and Horseshoe Bend) General Andrew

Jackson to take action with respect to the Seminoles. Jackson

interpreted this as being more than a call for the defense of the

American borders. With the coming of the next spring (April and May of

1818) he invaded Florida, not only decisively defeating the Seminoles

but seizing all of Spanish Florida, declaring it to be thus a territory

of the United States. President Monroe and his secretary of state, John

Quincy Adams, were embarrassed. But the American nation was thrilled by

Jackson's heroics.

Spain at this point decided that wisdom called

simply for the sale of Florida to the United States (for the price of

$5 million) confirmed in the Adams Onis Treaty of 1819. With the

American payment in 1821 of that sum, the United States in fact came

into undisputed possession of Florida.

|

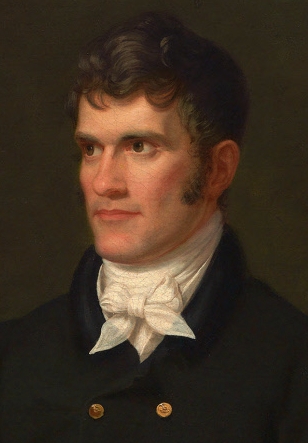

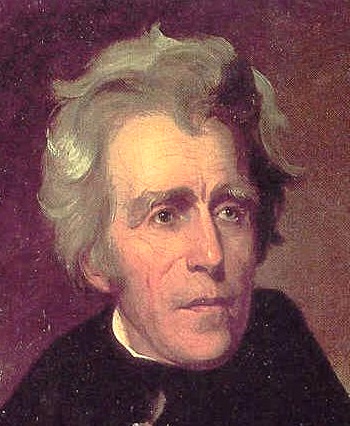

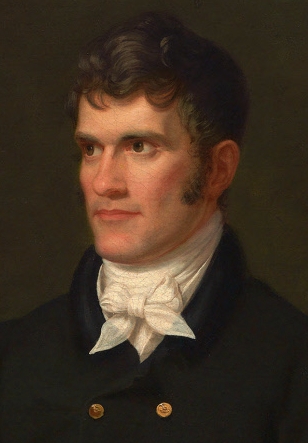

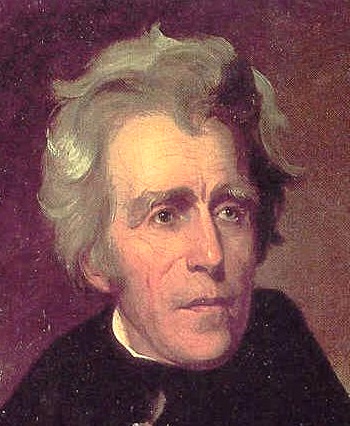

John C. Calhoun (Secretary of War)

General Andrew Jackson

Calhoun ordered Jackson to protect Americans from Seminole Indian raids coming from Florida. Jackson took that as authorization to invade Florida in 1818 and destroy Seminole power. The embarrassed Spanish then simply sold Florida to America for $5 million!

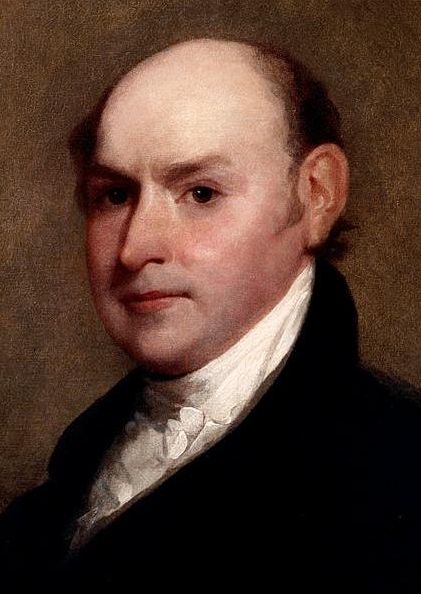

Secretary of State John Quincy

Adams – by Gilbert Stuart (1818)

The White

House

THE

MISSOURI COMPROMISE (1820) |

| In

1819, Missouri applied for statehood, opening up a bitter controversy

arising from the question about whether Missouri would enter the Union

as a slave or free state. At this point there was a balance of eleven

free and eleven slave states making up the Union. But the balance was

precarious, stirring fears of the Southern slave states that adding

more states would swamp them in an anti-slave mood arising from the

North. Slavery had been forbidden in the states of the Northwest

Territory. And Louisiana had been admitted in 1812 as a slave state,

and thus there was some kind of expectation that future Southern states

would join the ranks of the slave states. But Missouri was a border

state, with slavery practiced in parts of the state, but not in others.

Was Missouri thus to be considered slave or free?

The Constitution itself made no mention of the

issue, although one of the last acts of the Continental Congress in

1789 was to set up the Northwest Territory as a free zone forbidding

slavery, indicating that the federal Congress might have such authority

as well concerning the admission of territories as new states. The

Southern states claimed that the issue was entirely a state issue, not

a federal issue; each state could of its own decide whether it was to

be a slave state or not.

Nonetheless, slavery was not really a legal issue

as much as a deep moral issue, with slavery clearly coming under ever

deeper moral questioning.1 This made the Southern states all the more

uneasy, because the lifestyle, the Southern fantasy of living the life

of plantation aristocracy, as well as the tobacco/cotton economy itself

was completely dependent on the institution of slavery. There was no

longer any talk in the South about the institution simply withering

away by itself. Indeed, any talk of limiting the institution was taken

as an insult or threat to Southern culture.

But the North was deeply involved in a spiritual

movement of Christian revival, in which slavery certainly appeared to

be one of the sins of the nation that needed cleansing. The abolition

of slavery was indeed soon to become a major topic of conversation in

the North, a conversation that made the South very nervous.

On top of this, the population of the North was

expanding much more rapidly than that of the South because the freer

culture made for greater personal opportunity. It thus drew

adventuresome Americans – and even Europeans – to the North rather than

the South for settlement.

All this tension came to a head with the question

of admitting Missouri as the twenty-third state. But then Maine

requested entry into the Union as a new state, and the possibility of

compromise seemed to present itself.

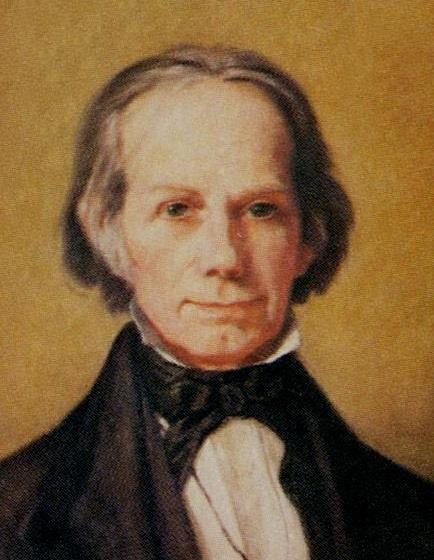

Henry Clay – the Great Compromiser

Henry Clay of Kentucky stepped forward to offer

specifics as to how this compromise might be achieved. As a package

deal, Clay proposed admitting both states – one slave, one free – thus

preserving the balance, coupling this with the stipulations that a line

would be drawn across the country at the 36 30' parallel running west

from the Mississippi River, distinguishing future slave and free

states. This would run along the southern border of Missouri, but

exempt Missouri, allowing it to be admitted as a slave state. He added

also the provision that the property interests of Southern slave-owners

would be fully protected, including the return of runaways and the

ability of Southerners to travel north with their slaves without the

fear of the legal loss of their slaves once in the North. And he

cleverly bundled this as a single proposal so that it could not be

amended by those wanting to pick its provisions apart.

At the time this compromise seemed to be a

brilliant solution to the problem, which many hoped would now go away

as an issue. But Clay's compromise did not solve the problem. Instead

it brought out into ever-stronger light the deep moral-cultural

division separating the North from the South, a division that clearly

was not going to go away on its own and indeed would only grow larger

with the recurring matter of the country's taking in new states to the

West.

1Prior

to the War of Independence – even during the Great Awakening of the

mid–1700s – most Americans avoided the issue concerning the evils of

slavery, even as an additional 150,000 slaves were imported to America

from the 1720s to the 1760s. But the Quaker John Woolman took up the

cause in the 1740s, and in 1758 was instrumental in getting the Yearly

Meeting to set up a committee to look into this issue. But this was

merely a very slow start of what eventually would become Abolitionism.

Henry Clay -

"The Great Compromiser" – by Matthew Haris Jouett (1818)

Transylvania University – Lexington, Kentucky

THE "MONROE DOCTRINE" (1823) |

| Meanwhile,

with Spain caught up in a struggle at home in Europe between

Republicans and Monarchists, Spanish power overseas in the Americas

was clearly slipping. After ten years of struggle, New Spain or

"Mexico" finally (1821) secured its independence from an exhausted

Spain – with Central America following right behind.

When in 1822 France, backed by other monarchs of

continental Europe, moved to oust a constitutional republic in Spain

and restore the country to monarchy, concern developed in America that

Spain, or even (and more likely) France, might want to impose imperial

rule in the Americas again. But Britain was just as alarmed as America

about this. Britain had its own reasons for not wanting to see this

happen. Britain was always suspicious of any rising European power that

might upset the balance of power on the continent and overseas, for

such a development would usually end up isolating Britain from the rest

of Europe (and from the lucrative overseas trade that Britain's economy

depended on), always a dangerous position for Britain to find itself

in. Britain had been developing growing commercial relations with the

newly independent republics of the former Spanish (and Portuguese)

Empires in America, which they did not want to lose through a renewal

of Spanish (or French) imperial or mercantilist designs2 on the

Americas.

Thus it was that British Foreign Secretary Canning

inquired of Monroe's secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, the son of

the former president, John Adams, about America's interest in a policy

of blocking the restoration of European imperialism in the Americas. It

was understood that the British navy would be ultimately the enforcing

agency of such a policy, but without any formal connection (which might

also stir up accusations about Adams being pro-British).

The answer was in the affirmative, and took the

form of a message to Congress by Monroe in 1823 (actually written by

Adams), in which Monroe made it clear that the Americas had a destiny

separate from Europe's, and America would defend that separation by

whatever means necessary. European monarchs scoffed at Monroe's

presumptuousness, but in fact were well aware of the reality of British

interests behind this pronouncement and did not actually challenge it.

2Mercantilism

was commonly practiced in European imperialism, in which only the

European mother country was allowed to trade with its overseas colonies.

British Foreign Secretary George Canning

MONROE'S FINAL YEARS AS PRESIDENT (1823-1825) |

| And

thus it was that Monroe finished out his presidency in 1825 with the

country once again in excellent shape. The economy was booming with the

expansion of American industry and trade, the American population was

expanding to lay full claim to its western territories, and America

found itself in no major crisis with one or another of the major

European powers. The Era of Good Feelings had been restored!

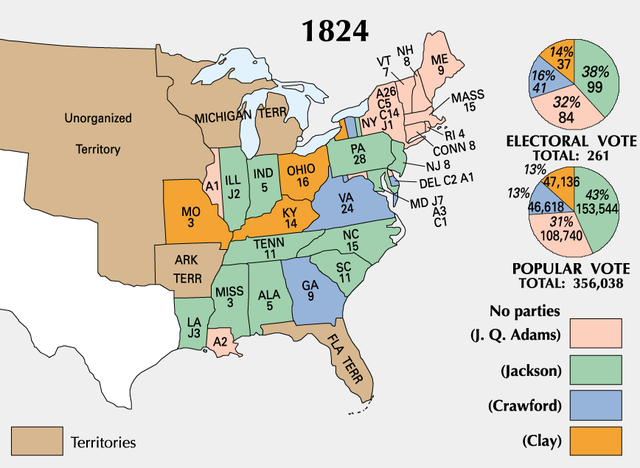

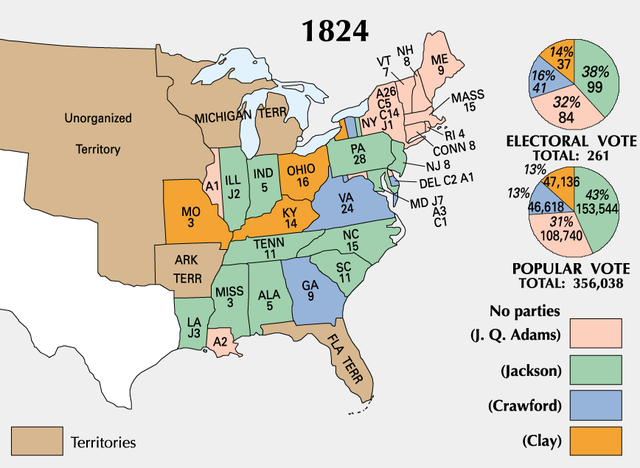

The election of 1824. With the collapse of the

Federalist Party, the American two-party system had thus also

collapsed, complicating greatly the selection of candidates for the

presidential election. The Republican Party itself was consequently

split into a number of contending factions, built mostly around

prominent personalities, the various geographic regions that supported

them, and the spoils system of political rewards that generated

widespread personal support for the leaders in Washington (with the

notable exception of John Quincy Adams who found such political

wheeling and dealing to be personally distasteful).

Four different candidates presented themselves for

the presidency, John Quincy Adams, William Crawford, Henry Clay and

Andrew Jackson. As a consequence, none of them received a majority vote

(at least 50 percent of the total vote) and the election of the

president (according to the Twelfth Amendment) was given to the House

of Representatives to decide. But only three candidates were eligible

for consideration under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment.

Jackson had received by far the most popular votes of the four (though

only a small plurality in the electoral college) and was expecting the

House to elect him. Clay, who was the fourth in the electoral count and

thus not eligible for House consideration, nonetheless commanded

considerable power in the House of Representatives as its Speaker. Clay

personally disliked Jackson and was closer to Adams in political

thinking. He convinced his supporters in the House to vote for Adams,

giving Adams a full majority on the first ballot, and thus the

presidency.

|

Prosperity had returned to the country ... and indeed it was finally an "Era of Good Feelings"

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS (PRESIDENT

1825-1829) |

| Then

when Adams named Clay to be his secretary of state (so far, the one

position that seemed a natural stepping stone to the presidency),

Jackson exploded in fury. He claimed that the deal was simply a corrupt

bargain,3 and hammered away on that claim for the next four years.

John Quincy Adams was much like his father, John

Adams, lacking personal charm or charisma, but possessing a brilliant

mind and a strong moral character. He did not particularly like

politics, or even the office of presidency, and did very little to

build up a corps of political support beneath him. He preferred to

focus instead on programming various physical and intellectual

improvements for the nation, from roads and canals, to the

encouragement of industry, to the advancement of education, to the

support of the sciences. He worked hard to reduce greatly the national

debt. But he faced tremendous opposition from Jackson and his

supporters in Congress on every one of his programs.

He did not have an extensive foreign policy

program to deal with because as the former secretary of state he had

overseen tremendous improvements in the country's international

position. He also believed that it was America's duty to not act the

part of an ambitious imperialist nation, but instead to focus on the

development of the Republic at home.

He tried to be fair in the handling of the

nation's relations with the Indians – especially concerning the land

rights of the large Cherokee nation in the American Southeast.4 But on

this issue Jackson's opposition was extremely strong, as this was a

matter of great interest to Jackson's natural constituency of Southern

and Western Whites, who were demanding that the Indians be removed to a

location somewhere West of the Mississippi River.

Overall, John Quincy Adams, though an excellent

administrator as U.S. president, was sadly out of touch with a dynamic

America, which others, such as Jackson, understood instinctively. Thus

Adams would serve only one term as president.

3This

was quite an unfair accusation, as Clay was an outstanding statesman,

very well suited for the job. Jackson's team in fact had also courted

Clay in the hopes that he would swing his votes in the House towards

Jackson. Part of Jackson's fury was a result of Clay's earlier strong

stand in Congress against Jackson's invasion and grab of Florida.

4The

Cherokee had gone to great lengths to accommodate themselves to Anglo

culture, most of them becoming Christians and giving up their hunting

economy to become settled farmers like the Whites. Although they

presented no danger to the Whites, Southern Whites could not get past

their general hatred of all Indians – or anyway the general hunger to

confiscate Indian lands.

John

Quincy Adams Andrew

Jackson

John

Quincy Adams Andrew

Jackson

William Crawford Henry Clay

|

With no majority in the electoral college, the vote was sent to the House of Representatives. Clay threw his support to Adams. Thus Adams was elected President. Jackson was furious.

The "Era of Good Feelings" continues on into the four years of the Adams presidency

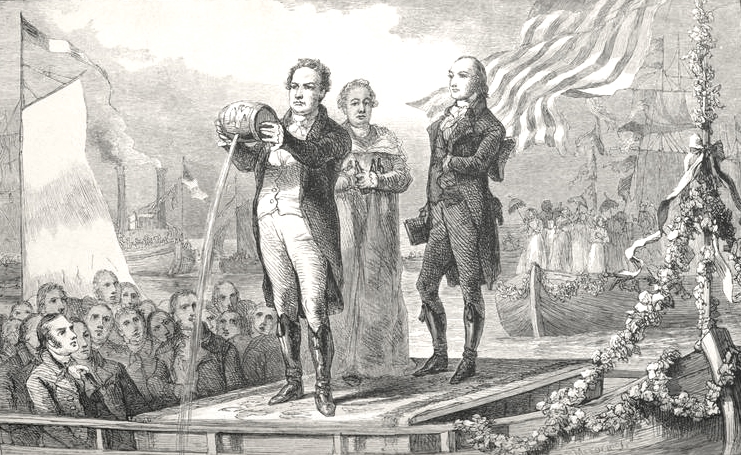

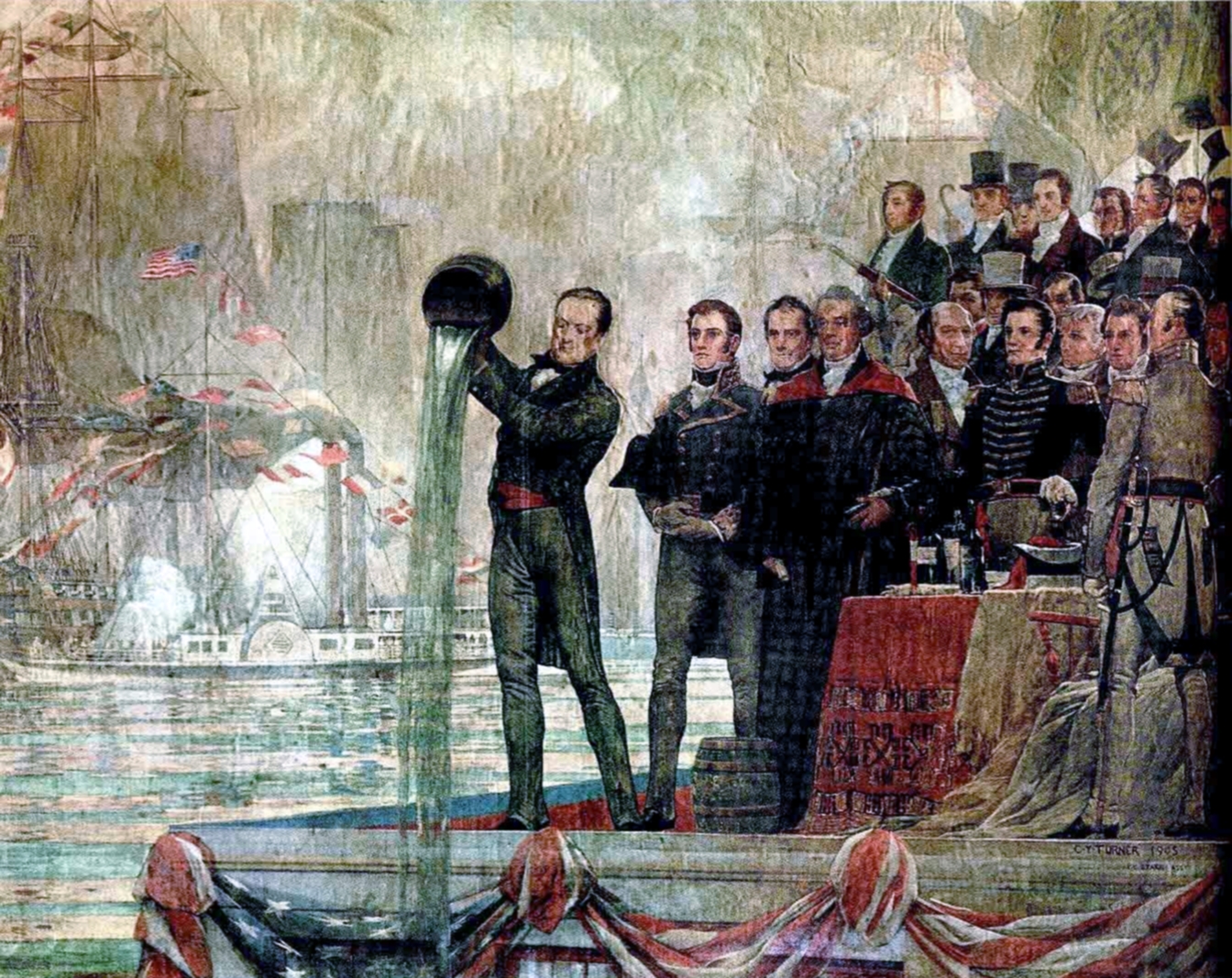

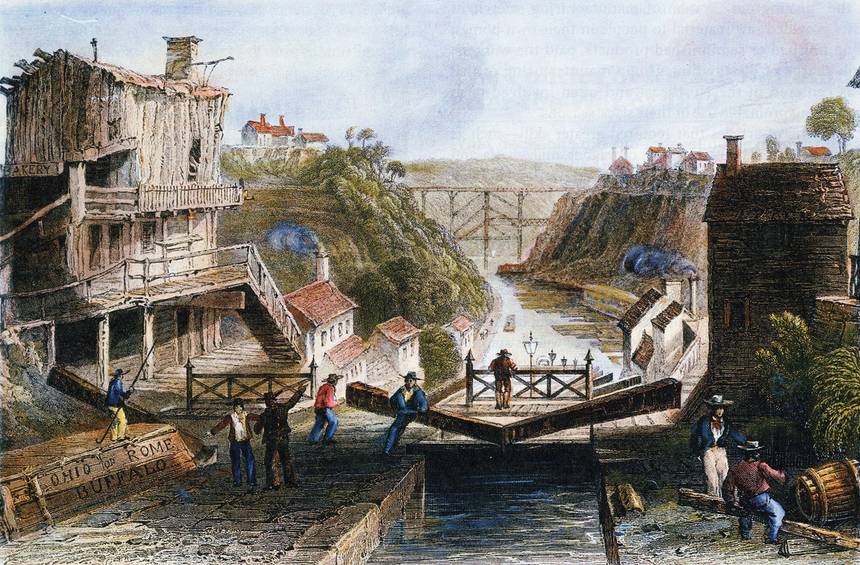

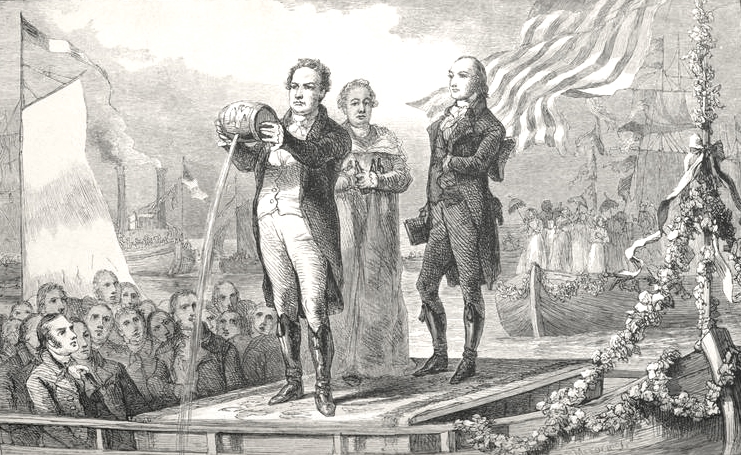

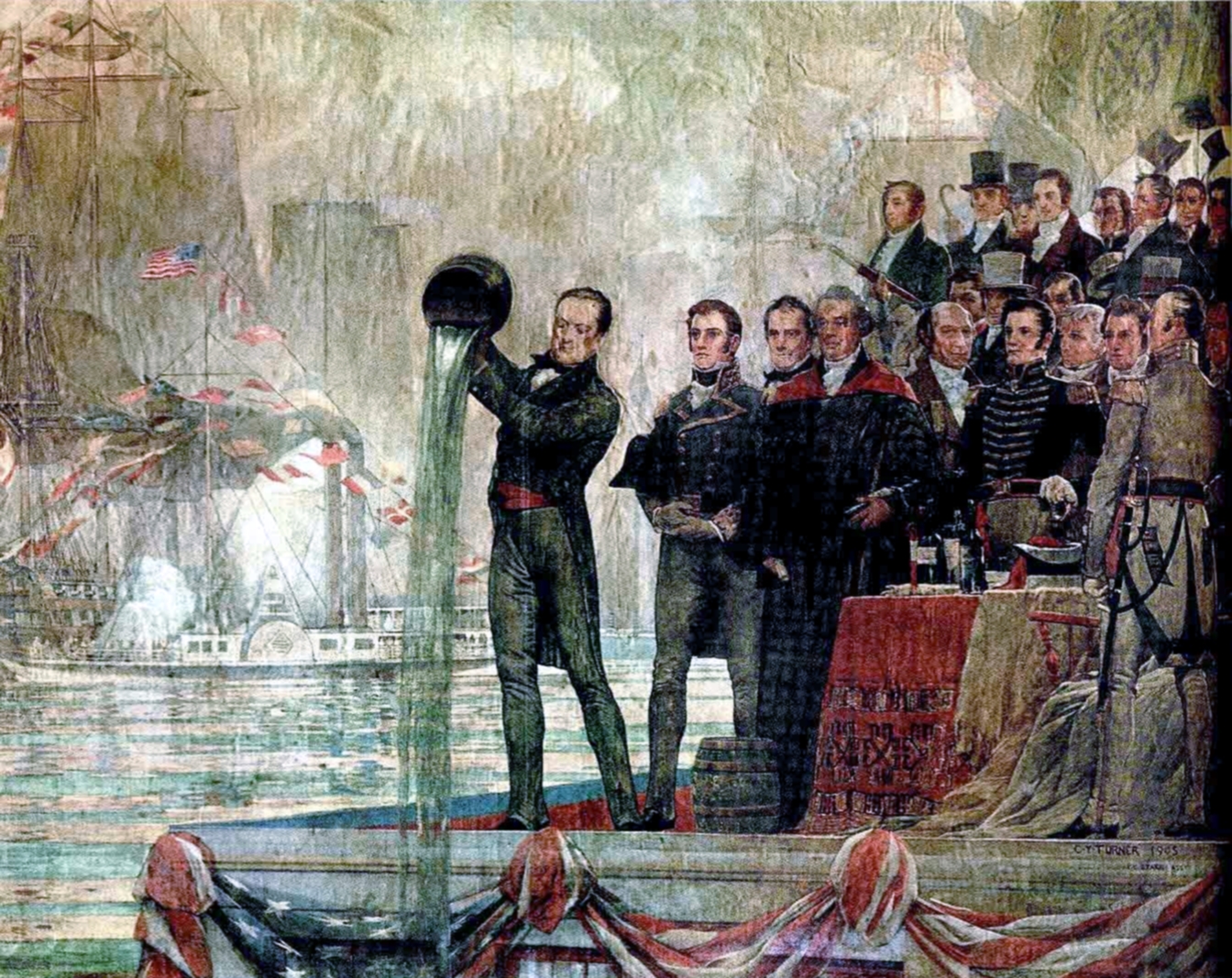

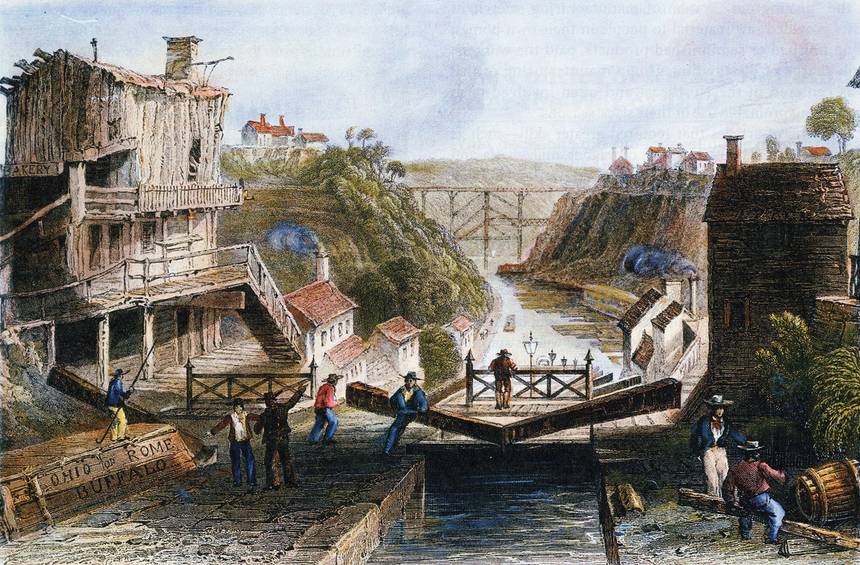

New York Governor DeWitt Clinton

Authorized the building of the 363-mile Erie Canal (1817) which opened for business in 1825 ... and a big supporter of industrial development in general

As overseer of the project, Dewitt Clinton, mingles the waters of Lake Erie and the Atlantic upon the completion of the Erie Canal (October 1825)

Another portrayal of the event

One of the locks on the Erie Canal

THE TOUGH QUESTION OF

INDIAN vs. ANGLO LAND RIGHTS |

|

The English/American understanding of land ownership

Land – Indian land – had long been a big part of

America's sense of personal salvation. Americans understood that God

saved the soul. But they also understood that land saved the body! From

the very moment that Americans landed on the Atlantic or Eastern shores

of North America they had developed a very strong interest in the land,

the low mountains and dark forests that lay just to the West of them.

The Indians who lived on that land were not numerous and thus the lands

seemed virtually empty, just waiting for the English colonists to come

and settle there.

At first the English settlers and Indian hunters

attempted to stay on friendly terms with each other. But their concepts

of land ownership were so different that conflict – deadly conflict –

was inevitable. To the English, land ownership was demonstrated in a

person's working of that land. Whoever cleared the land, cut back the

forest and planted crops in these new clearings could claim

unchallenged title to the land. Idle land, land that was not farmed or

grazed, was not owned by anyone. Indeed, unfarmed land was simply

uninhabited land. Thus the Indians as hunters requiring the woodlands

for the survival of the game they hunted just did not factor into the

English understanding of things.

To the English way of thinking, Indian land was

simply there waiting for the taking by some industrious individual. But

according to the Indian way of thinking, the land was there for

hunting, not farming – and the English were no more than thieves,

stealing their land.

In this contest for the land the Indians were

technologically, numerically, and socially greatly outmatched. Not only

did the English settlers possess superior weapons, they also had more

highly disciplined or unified social power. The Indians were not only

small in number on the land, they were highly divided among themselves – ancient enemies, one small tribe against another. The Indians thus

were tremendously handicapped in their efforts to hold back English

expansion into their ancestral territories. Consequently, by the early

1800s, the expansion into the Indian lands of the West and South by

land-hungry Anglo-Americans was rapid.

There had been efforts from time to time, even

from the beginning of the earliest English settlements, to legalize or

regularize this question of land ownership. For the English this was

done through written legal assignments of the land in the form of

deeds. Such legal assignments not only awarded ownership to an

individual but also to that individual the rights of transfer of that

land to another – as a grant (often in marriage, often as the terms of

peace after a war) or as a sale. Treaties as a follow-up to a war very

often included the idea of the transfer of land from one individual (a

king, for instance) to another.

The weight or worth of treaties

Indians were aware of such arrangements – entering

into arrangements among themselves similar to the European concept of

treaty. And thus on many occasions the English and tribal chiefs

transacted land deals – that is, entered into treaties with one

another. The Dutch thus purchased the island of Manhattan for their New

Amsterdam, and Roger Williams also purchased from the local tribes

the land at the head of the Narragansett Bay for his Providence Colony.

But in general, even this nicety was ignored by the English who pushed

into Indian lands to make way for their own settlements, unaware of or

ignoring the Indians' land rights.

There often were treaties signed between the

English and the Indians – usually following another bitter conflict or

local land war. These treaties usually simply acknowledged another loss

of land by the Indians, though they were frequently accompanied by some

comforting section which recognized the rights of the same Indians to

other, uncontested territory. But treaties back in Europe among kings

had very little longevity – quickly broken by their kings at the

earliest opportunity. And so it was with the treaties the English

signed with the Indians. These agreements were treated with the same

lack of sense of anything permanent about them. This the Indians did

not understand, for their idea of a treaty was that it formed a

perpetual or permanent right to land use, one that would be handed down

as a matter of honor by generation after generation. Sadly, the Indians

were to learn that things just did not work this way with the English.

Besides, frontiersmen paid little attention to the

land arrangements entered into with the Indians by their colonial

governments. Such governments were far away and the local frontiersmen

lived in a world far removed from the halls of the colonial

governments. Frontiersmen conducted their own affairs pretty much as

they saw fit, regardless of what the colonial authorities had agreed

to.

The Christian understanding of all this

Why didn't Christianity soften this kind of

hard-handed land seizure? Christians after all were instructed by Jesus

to love their neighbor as themselves. But their Bible also told them of

the command of God to the Israelites to enter the land of the

Canaanites and clear it of both the people and even the herds and

flocks of the Canaanites. This was a necessary precondition for God to

be able to settle the Promised Land with his Chosen People.

Of the two viewpoints, Christlike love or

Israelite aggression, when it came to dealing with the Indians, the

tendency of Christian America was to take the Old Testament approach.

Christian Americans generally saw themselves under the same

instructions by God to clear the land to make way for the People of

God.

The huge demographic or population pressures behind the expansion

Anyway, whatever the legal or moral points

involved in this takeover of the land, there was little likelihood that

the Indians were going to be able to hold back the flood of Europeans

into their tribal territories.

Since the late 1300s the European population had

exploded and land hunger in Europe was very intense. This was the case

not just in England but in the Netherlands and in German-speaking

central Europe. The English first attempted in the 1500s to put excess

population in Ireland, this being justified in the English mind by the

primitiveness of Irish society (in the same way English land settlement

would soon be justified in America). But some of this Irish land soon

filled up with settlers from Scotland – the Scots-Irish – who in turn

(by the early 1700s) would push on to America and become major settlers

along the American-Indian borderlands or frontiers.

Even by the time of American independence,

numerous European settlers in America had left the coastal lowlands

along the Atlantic coast and were settling in various places in the

Appalachian Mountains to the West. Some had even crossed those

mountains and had begun to settle in the rolling hills of Kentucky and

Tennessee to the West of the Mountains.

As we have seen, one of the last tasks of the

Continental Congress in 1787 was to design an orderly system of

settlement of the land in the Northwest Territory awarded the Americans

in their peace settlement that ended the War of Independence with the

English. Swift action was required to get settlers into these

territories – before the English found some new excuse to break the

peace treaty with the Americans and seize these lands again.

Of course, the Indians were not consulted in this

matter. They, as "savages," counted not at all in the plans to map out

a program of systematic land development in the West.

And now that the legal reach of Anglo-America

extended, through the Louisiana Purchase, even to the Rockies (and

possibly beyond), life was going to become very tough for the American

Indian.

|

Go on to the next section: The Jacksonian "Democratic Revolution"

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | |

James Monroe (the fourth

James Monroe (the fourth The economic Panic of 1819-1821

The economic Panic of 1819-1821 The Missouri Compromise (1820)

The Missouri Compromise (1820) Monroe's final years as president

Monroe's final years as president John Quincy Adams – President

John Quincy Adams – President The tough question of Indian vs.

The tough question of Indian vs.