2. THE COLONIES MATURE

THE VARIETY AND NATURE OF THE AMERICAN COLONIES

Corporate colonies

Corporate colonies Proprietary colonies

Proprietary colonies  Royal or crown colonies

Royal or crown coloniesThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 42-52.

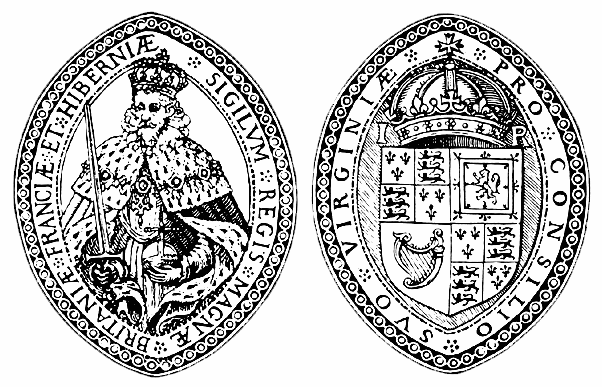

Thus far we have seen colonies of the types that

might be termed a corporate colony, that is, set up and run as a huge

corporation -

such as the Virginia, Plymouth, and Massachusetts Bay

colonies. The corporate colony followed a procedure that is still

used today

when we incorporate businesses, creating them as legal persons by the

consent of the government (English kings back then) according to

specific

terms listed in their incorporating charter. These legal

corporations were/are subject by the governing authority to taxation

and to periodic review of

their operations to ensure that they continue to serve the purpose to

which

they were incorporated. If they violate this trust, they might

lose their

charter rights and be dissolved - as was the Virginia Company in 1624.

|

|

There

was another type of colony that was also in existence, the proprietary

colony. The king, in a feudal-like manner, could grant portions of his

kingdom, which included the English territories in America, to personal

supporters for whatever reason that moved the king to do so. The king

often paid off royal debts this way - or just simply granted the land

as a special favor to an individual or group of individuals who had

been particularly supportive of his rule.

Those favored by the king (usually always English

noblemen) were given proprietorship over the colony by the king, much

like a personal fiefdom. They received not only a huge land grant but

also royal permission as personal proprietor over this colony to rule

it in an absolute fashion - much like a medieval baron. For instance,

Maryland (chartered in 1632) was a proprietary colony. The Calverts

(Lords Baltimore, father and son) were entitled to govern their colony

as they saw fit, develop whatever governmental institutions they found

helpful to their rule, and even distribute portions of their land grant

to whomever they wished - creating their own lord/vassal feudal

relationship. They owed loyalty to the king, of course, with an

understood promise to support him whenever the need arose from such

personal resources as their properties supposedly offered. But what

they did with their colonies was strictly the proprietors' business.

Usually this involved granting portions of it to their own friends and

putting other portions up for rent, offering land to tenants who in

turn would pay the proprietors an annual quitrent.

In general, the nobility who received lordship

over these proprietary land grants were not terribly interested in

actually living there. And they also had a very difficult time of it

collecting the quitrents owed them. Thus these proprietary ventures

tended not to turn out to be good money-makers for the proprietors.

George Calvert - Lord Baltimore (Catholic convert)

Petitioned King Charles for land north along the Chesapeake Bay

but died in 1629 before the royal award was made

Lord Cecil Calvert - George's son and Proprietor of the Maryland Colony. Despite it being a "Catholic" colony, he recruited settlers from all Christian faiths.

ROYAL OR CROWN COLONIES |

A

third type of colony came into being, usually from the failure of one

or another of the chartered corporation colonies to perform as the

English king had come to expect (such as Virginia in 1624) - or through

shifts in the political scene which would cause the English government

to seize a proprietary colony (as was the case of Maryland in 1689 -

although the colony was returned to the Calvert family in 1715). The

king would rescind or terminate the colony's original charter,

re-charter it as a crown colony, and send a royal governor to the

colony to rule it in the name of the king.

This was generally not a popular move in the

colonies. When in 1687 King James II wanted to convert the Connecticut

colony from a largely self-running corporate colony to a royal colony

run directly by him, Patriots hid the Connecticut Charter in the cavity

of an enormous oak tree to keep it from falling into the king's hands.

Of course it ultimately failed to stop the king. But nonetheless it was

well-remembered as an early act of defiance of the colonists in

protecting their liberties from a king who was determined to hold in

his own hands all powers of life and death over his subjects.

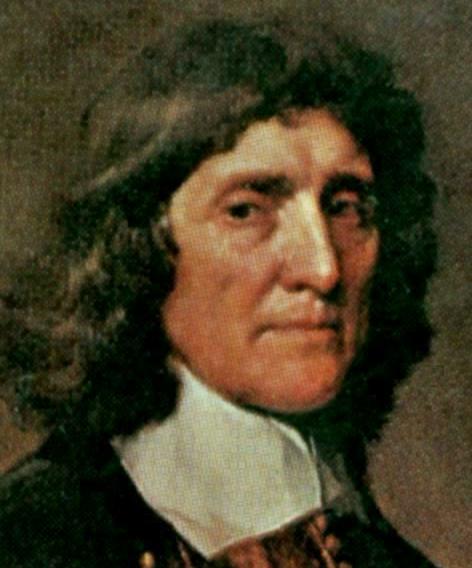

James II of England - by Nicolas de Largilliere,

ca.1686

British King,

1685-1688

National Maritime

Museum,

London

The

fabled Charter Oak Tree in which the Connecticut Charter was hidden to

keep it from the hands of King James II who wanted to turn this

independent corporate colony into a royal colony, ruled directly by the

King's governor under James's direct authority.

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges