2. THE COLONIES MATURE

COLONIAL SOCIETY IN THE 1700S

Southern culture continues to pursue its

Southern culture continues to pursue its

aristocratic dream

Georgia – the last of the original thirteen

Georgia – the last of the original thirteen

colonies

A "Great Awakening" restores the

A "Great Awakening" restores the

Christian spirit in the colonies

Colonial population and culture

Colonial population and culture

The economic growth of the colonies

The economic growth of the colonies

Colonial government

Colonial government

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 98-105.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

The

last of the American colonies, Georgia, chartered by King George in

1732, was quite different in conception from the others. It was not

designed originally as either a place of religious refuge or a

money-making venture, though certainly it was hoped that the Georgia

colony would be able to cover its expenses. It was primarily a military

colony, with the additional idea in mind that it could be a place to

resettle England's poor, languishing in England's prisons because of

debt.

|

A "GREAT AWAKENING" SUDDENLY AND MYSTERIOUSLY RESTORES THE CHRISTIAN SPIRIT IN THE COLONIES |

Then

around 1740, just as it appeared that the Christian foundations of

early America were about to die out for lack of spiritual interest or

even cultural support, something mysterious infected the American

heart. The "Great Awakening"1 suddenly broke out upon the American

scene to restore the warmth of American affection for God and Jesus –

and the belief again in God's full sovereignty in America.

This involved an enormous religious revival,

drawing thousands of Americans who gathered in open fields to hear

evangelists call them back to the old-time religion that their Puritan

ancestors had known Christianity to be. This not only rekindled the

American sense of being a Covenant people, but in the process

revitalized the American sense of the basic equality of all people

because according to these revivalist preachers (and the Puritan

fathers before them) in the eyes of God all people were indeed equal.

Actually,

something of this strong revivalist nature had started some dozen years

earlier (1725-1726), just here and there in New England and in the

Middle Colonies. Theodore Frelinghuysen had been given the task of

pastoring a number of small Dutch Reformed Churches in the Raritan

Valley of New Jersey. He understood his central responsibility was to

bring the wandering Christian souls back in line with a faith rather

than works approach to their Christian life. He issued a strong call to

the faithful for repentance, and a return to God as the guiding force

in their lives. This call challenged them to take up something much

more rigorous than just regular church attendance and proper Christian

moral behavior. This was a call for a deep renewal of the people's

faith in God personally as director of their lives.

Something of the same nature was going on at about

the same time in nearby Central New Jersey. William Tennent and his

sons, particularly Gilbert, found themselves deeply committed to

issuing to the Presbyterian congregations of the area a similar

evangelical call to spiritual repentance and revival of their Christian

faith.

1The

term "Great Awakening" was first applied to this event with the

publication in 1845 of Joseph Tracey's book, The Great Awakening: A

History of the Revival of Religion in the Time of Edwards and

Whitefield.

Tennent's Log College founded in 1727 in Eastern Pennsylvania by the

elder (William) Tennent to train "New Side" (Evangelical) Presbyterian

ministers (helping to split the denomination into New and Old Side Presbyterians). In 1746 the college was moved to New Jersey (ultimately Princeton in 1756) by the younger Gilbert and Jonathan Dickinson ... becoming the College of New Jersey (one-sixth of the Framers of the US Constitution were graduates of this College) ... changing its name in 1896 to Princeton University. Nassau Hall – College of New Jersey (Princeton) – 1764

But all the emotionalism of such Christian revival

began to stir the ire of some of the other pastors of New England and

the Middle Colonies. And briefly it appeared that the whole thing would

soon die away.

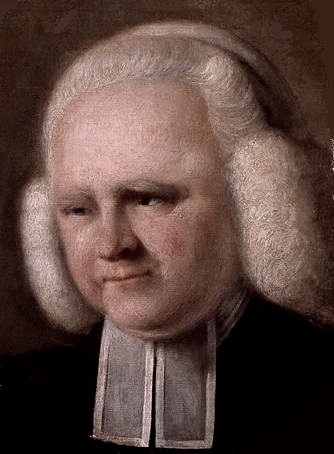

Meanwhile across the Atlantic

in England something of the same nature was taking place, led

principally by the English Calvinist reformer George Whitefield

(pronounced Whit-field) and his close friends, the Anglican reformers2

John and Charles Wesley. They developed their close relationship

(despite some theological differences) during their years at Oxford

University where they created and led the Holy Club – before, at

different points in time, heading off as pastors for a couple of years

to the colony of Georgia to be part of the philanthropic idealism that

supposedly had founded this new colony. But John Wesley would soon return to

England after rather uninspiring efforts in Georgia, something that

broke Wesley's heart. But this humbling experience in turn opened him

to a truly born-again experience.

Soon a spirit of revival rather dramatically took

hold of both Wesley's and Whitefield's ministries. In 1739 this spirit

took at first Whitefield and then John Wesley out into open fields to

preach the message of salvation to the English working class. Such

open-air preaching was a dramatic departure from the type of pulpit

preaching expected of pastors. But while this irritated some of the

Christian faithful, it succeeded in reaching thousands of people who

otherwise would never have found themselves inside a church except for

a wedding or a funeral. Something new was happening here!

In 1740 Whitefield returned to Georgia to found an

orphanage – and then moved on to Pennsylvania to do the same there (in

partnership with some Moravians), also preaching every day as he made

his way across the colonies. Gradually word began to spread among the

colonies about this revivalist preacher Whitefield who was invited (as

was customary) to preach in various churches along the way.

Meanwhile, Tennent and Edwards linked up with

Whitefield, inviting Whitefield to New Jersey and New England to preach

there. With this, full revival began to break out, not just in

Northampton and Central New Jersey but at various points throughout the

colonies – as Whitefield now preached his way from New England in the

north to Georgia in the South. Thus Whitefield found that his mission

was no longer orphanages but simply a continuation of his preaching,

wherever the Spirit directed his path.

But having found it also easy in England to preach

in open-air settings (fields and town squares), he proceeded to do the

same in America. For some, this was quite a bit too much and now he

found some church doors closing on him. But he continued to preach

open-air style anyway.3

Jonathan EdwardsActually,

something of this strong revivalist nature had

Likewise, to the north in New England,

elements of a similar spiritual revival were undertaken during the

mid-1730s by Jonathan Edwards at his quite large Congregationalist

church in Northampton, Massachusetts. There was a deep earnestness on

Edward's part concerning the sinfulness of the faithful and the need

for repentance, which stirred the emotions deeply of his congregation.

Some 300 people were brought into fellowship with Edwards' congregation

during that period.

2Or

"Methodists" as they had previously been termed contemptuously by their

peers in their college days, because of the spiritual disciplines they

put themselves under in order to strengthen their faith and to support

their work. John was the evangelical preacher and organizer,

Charles the writer of popular hymns ... such as "Hark, the Herald

Angels Sing," and "Christ the Lord is Ris'n Today."

3While Whitefield was busy developing Christian revival in America, his friend John Wesley was busy doing the same in England, thus founding there what was to become the Methodist movement. Eventually (1760 and after) Wesley's Methodist movement would come to America – still considering itself an integral part of the Church of England and under its discipline. But in 1784, with America's break from England following its War of Independence, the Wesleyan or "Methodist" movement in America would reform itself as the Methodist Episcopal Church, coming under its own bishops, Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury. At this point the Methodist Church would truly take off as a massive revival movement, especially as a result of the extensive work of the Methodist circuit riders who carried the spirit of revival to the rapidly expanding American frontier – making it a part of the "Second Great Awakening" that shook the young Republic in its early years (1790s to mid–1800s).

The Impact of the Great Awakening

Edwards himself became a major figure in this broader revival, with his preaching in 1741 in his church in Massachusetts and then again in Connecticut his famous sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." Although Edwards did not take up the fiery style of Whitefield, his calmly presented sermons had much the same effect on his listeners: repentance and the call to salvation.

The effect of this revivalist preaching was overwhelming. Revival swept like a whirlwind everywhere throughout the colonies, especially in the years 1741-1743. This first truly all-American event went far not only in restoring a deep spirituality in America but also giving the colonists from the North to the South a sense of being a unique people, something akin to a nation. Americans now had national heroes as Americans, revivalists and missionaries well known up and down the colonies as part of the common experience of American life. Whitefield became very well-known from Maine to Georgia, moving up and down the American colonies over the course of the thirty-two-year period (1738-1770) when he visited America numerous times to preach revival.

Also the heroic story of the young Presbyterian missionary (and friend of Edwards), David Brainerd, who wore himself out (tuberculosis) preaching a similar revival to the Indians, was well known across the colonies, making him something of a national hero. And the Presbyterian minister Samuel Davies became a powerful instrument in reaching not only frontiersmen but also African slaves in Virginia with the gospel message. Furthermore, the sermons of the revivalist preachers (especially Edwards' sermons) were read widely throughout the colonies.

The message of this revival was clear and unvarying: God was calling the Americans out of their spiritual slumber to a repentance that would prepare them for a great work ahead of them. As citizens of the New World they had a huge calling on their lives from God to be his people as he, their one and only sovereign, led them. In taking up this call they would show the Old World of Europe, by America's own example, how a people could live to a new and glorious purpose in Christ.

Consequently, such a message repeated over and over again worked strongly to build something of a national spirit – a collective identity among the colonists as "Americans."

Not every

American got swept up in this Awakening. There were many hostile

critics among the American intellectuals who found this phenomenon most

improper.

Unfortunately, the excitement of the new style led

some enthusiastic pastors to go overboard in that enthusiasm. For

instance, James Davenport went all out not only in viciously attacking

people who had not embraced fully the revival, but going through

strange emotional highs himself publicly (possibly suffering from bouts

of insanity) in the service of his cause, which made it easy to be very

critical of the excessive enthusiasm of that cause.

Indeed, for many of the Old Light Christians (led

by the Boston pastor Charles Chauncy),4 revivalists preaching

emotionally charged sermons in open fields before thousands of common

farmers and tradesmen and women – rather than to parishioners properly

attired in their Sunday finery and seated properly in their pews in

church attentive to the theological details of a scholarly sermon – was

just not proper Christianity. Worse, such proper church-going

Christians being called out by the revivalists as sinners needing the

forgiveness of God no less than the sinners of the inferior social

ranks was considered by those proper Christians as an outrageous idea,

even an evil idea inspired by the Deceiver, Satan himself. Then too,

many pastors were simply bitterly jealous that while their churches

remained empty, hundreds – even thousands – of people found it easy

enough to gather in nearby fields to hear the preachers of spiritual

revival.5 But these critics were a small voice in the scheme of

things.

6

4But

Old Light Chauncy would be just as outspoken in his opposition when

talk began to develop (the beginning of the 1770s) in England about

placing the colonial churches of America under episcopal authority

(rule by bishops and archbishops – and ultimately the king of England

himself) of the Church of England. In fact Chauncy's sermons and

pamphlets in support of the colonies' War of Independence against

England were widely influential in the colonies.

5A

split in 1741 opened up also within the Presbyterian denomination

(heavily concentrated at the time in the middle colonies of New Jersey

and Pennsylvania) between the New Side and Old Side over the ordination

of pastors graduating from Gilbert Tennent's "Log College" (forerunner

of Princeton Seminary). New Siders were pro-revivalist pastors, whose

numbers increased dramatically – just as the Old Side pastors numbers

declined equally dramatically.

6Sadly

for Edwards, opposition to his style and message eventually developed

within his own church, and in 1750 he was voted out of his pulpit by a

quite large majority. He took himself off to preach to the Indians (but

still writing at the same time). But he was not forgotten in the larger

American world and in 1758 he was called to the presidency of the

Presbyterian New Sider's College of New Jersey (the future Princeton).

Charles Chauncy

Ben Franklin's Take on the Matter

Even the greatest American

sage of the time, Ben Franklin, found himself warmed at least

intellectually by this massive religious revival. In fact, he

personally saw to the publishing of forty or more of Whitefield's

sermons on the front page of his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette.

Indeed, Franklin and Whitefield formed a friendship that lasted the

entire span of Whitefield's remaining life (he died in 1770).

God knew that the Americans would need this

preparation for the days ahead when troubles would mount between the

Americans and the powers of Europe (and also the native Indians). No

amount of intellectual Rationalism would give courage to the American

colonials, who understood the sacrifices they were called to in taking

up the path of rebellion against their king, and the hangman's noose

that awaited them as traitors if this rebellion should fail. Americans

were going to need a strong faith in God's support in order not to lose

courage in the face of these deadly challenges. And so it was that the

Great Awakening was well timed to bring exactly such spiritual

preparation. God was being faithful to keep his side of the Covenant

with America.

COLONIAL

POPULATION AND CULTURE

THE

ECONOMIC GROWTH OF THE COLONIES

Boston's commercial

center:

State Street and the Old State House

Massachusetts Historical

Society

The Great Wagon Road

Baltimore in 1752

(by 1776 it was a busy seaport

and the 9th largest city in the colonies)

New York Public

Library

The Moravian settlement at

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania – 1757

Tobacco

Farming

COLONIAL

GOVERNMENT

4But Old Light Chauncy would be just as outspoken in his opposition when talk began to develop (the beginning of the 1770s) in England about placing the colonial churches of America under episcopal authority (rule by bishops and archbishops – and ultimately the king of England himself) of the Church of England. In fact Chauncy's sermons and pamphlets in support of the colonies' War of Independence against England were widely influential in the colonies.

5A split in 1741 opened up also within the Presbyterian denomination (heavily concentrated at the time in the middle colonies of New Jersey and Pennsylvania) between the New Side and Old Side over the ordination of pastors graduating from Gilbert Tennent's "Log College" (forerunner of Princeton Seminary). New Siders were pro-revivalist pastors, whose numbers increased dramatically – just as the Old Side pastors numbers declined equally dramatically.

Even the greatest American

sage of the time, Ben Franklin, found himself warmed at least

intellectually by this massive religious revival. In fact, he

personally saw to the publishing of forty or more of Whitefield's

sermons on the front page of his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette.

Indeed, Franklin and Whitefield formed a friendship that lasted the

entire span of Whitefield's remaining life (he died in 1770).

God knew that the Americans would need this

preparation for the days ahead when troubles would mount between the

Americans and the powers of Europe (and also the native Indians). No

amount of intellectual Rationalism would give courage to the American

colonials, who understood the sacrifices they were called to in taking

up the path of rebellion against their king, and the hangman's noose

that awaited them as traitors if this rebellion should fail. Americans

were going to need a strong faith in God's support in order not to lose

courage in the face of these deadly challenges. And so it was that the

Great Awakening was well timed to bring exactly such spiritual

preparation. God was being faithful to keep his side of the Covenant

with America.

COLONIAL

POPULATION AND CULTURE |

THE

ECONOMIC GROWTH OF THE COLONIES

Boston's commercial

center:

State Street and the Old State House

Massachusetts Historical

Society

The Great Wagon Road

Baltimore in 1752

(by 1776 it was a busy seaport

and the 9th largest city in the colonies)

New York Public

Library

The Moravian settlement at

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania – 1757

Tobacco

Farming

COLONIAL

GOVERNMENT

THE

ECONOMIC GROWTH OF THE COLONIES |

Boston's commercial center: State Street and the Old State House

Massachusetts Historical Society

The Great Wagon Road

(by 1776 it was a busy seaport and the 9th largest city in the colonies)

The Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania – 1757

Tobacco Farming

COLONIAL

GOVERNMENT |